Abstract

Patients at increased familial risk of cancer are sub-optimally identified and referred for genetic counseling. We describe a systematic model for information collection, screening and referral for hereditary cancer risk. Individuals from three different clinical and research populations were screened for hereditary cancer risk using a two-tier process: a 7-item screener followed by review of family history by a genetic counselor and application of published criteria. A total of 869 subjects participated in the study; 769 in this high risk population had increased familial cancer risk based on the screening questionnaire. Of these eligible participants, 500 (65.0 %) provided family histories and 332 (66.4 %) of these were found to be at high risk of a hereditary cancer syndrome, 102 (20.4 %) at moderate familial cancer risk, and 66 (13.2 %) at average risk. Three months following receipt of the risk result letter, nearly all respondents found the process at least somewhat helpful (98.4 %). All participants identified as high-risk were mailed a letter recommending genetic counseling and were provided appointment tools. After 1 year, only 13 (7.3 %) of 179 high risk respondents reported pursuit of recommended genetic counseling. Participants were willing to provide family history information for the purposes of risk assessment; however, few patients pursued recommended genetic services. This suggests that cancer family history registries are feasible and viable but that further research is needed to increase the uptake of genetic counseling.

Keywords: Hereditary, Genetic, Familial, Cancer, Family history, Genetic counseling, Uptake

Background

Up to 10 % of cancer is attributed to highly penetrant hereditary cancer syndromes (HCS) and more than 45 different HCS, associated with a broad range of cancers, have been described [1–3]. Identification of patients and families with HCS affects both cancer treatment and screening measures. For example, in the well-studied BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, deleterious mutations confer a significantly increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers as well as other cancers. For this reason, it is commonly accepted that increased cancer screening and cancer prevention measures should be considered [4]. Many other HCS also have clearly delineated cancer risks and effective screening and prevention protocols. Based on this evidence, consensus groups have published statements promoting the identification and genetic testing of individuals at increased hereditary risk of cancer, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American College of Medical Genetics, the National Society Genetic Counselors, the U.S. Multi-society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, among others [1, 5–10].

While referral to genetic counseling for high-risk families has been promoted, no routine risk assessment process has been systematically adopted for identifying patients in need of genetic counseling for cancer risks [11]. Several barriers to family history evaluation exist: insufficient collection of family history information by healthcare providers, poor identification of hereditary cancer indicators, insufficient or inappropriate referral for genetic counseling services, and inconsistent management of families at increased familial risk of cancer [12–18]. Thus there are inherent limitations to depending on providers to collect family history and identify at-risk patients. Comparatively, family cancer histories taken directly from the patient generally tend to be complete, coherent and most frequently accurate about first degree relatives [19]. Several paper and online programs to collect family history directly from patients have been developed; early reports suggest that patients will readily complete family history questionnaires and pursue genetics services without adverse psychological impact [20–24].

In order to address recommendations of identification and referral for cancer genetic counseling, we developed and studied the feasibility of a familial cancer registry as a means for family history collection as well as risk assessment. The breadth of hereditary cancer risk is described as part of the study as well as the adherence to recommendations for cancer genetic counseling for participants found to be at high risk for hereditary cancer.

Methods

Recruitment

From April 2009 through May 2011, three populations were identified for recruitment into the William C. Bernstein M.D. Familial Cancer Registry (“The Bernstein Registry”) at the University of Minnesota. The selection was a convenience sampling of volunteers presenting for cancer treatment or family history of cancer. One cohort, the Minnesota Colorectal Cancer Initiative (MCCI) registry, was a previous collection of participants triaged for hereditary colorectal cancer risk using a simple, paper-based family history questionnaire. The second group was from the patient population of the Women’s Health Clinic (WHC) at the University of Minnesota. This cohort was limited to women who received care at the WHC between September 2006 and September 2010 for ovarian, peritoneal, fallopian tube or endometrial (less than age 50) cancers or due to a family history of cancer. The third group consisted of women diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer (before age 50) ascertained through the affiliated Fairview Hospital Tumor Registry (FTR).

Study design

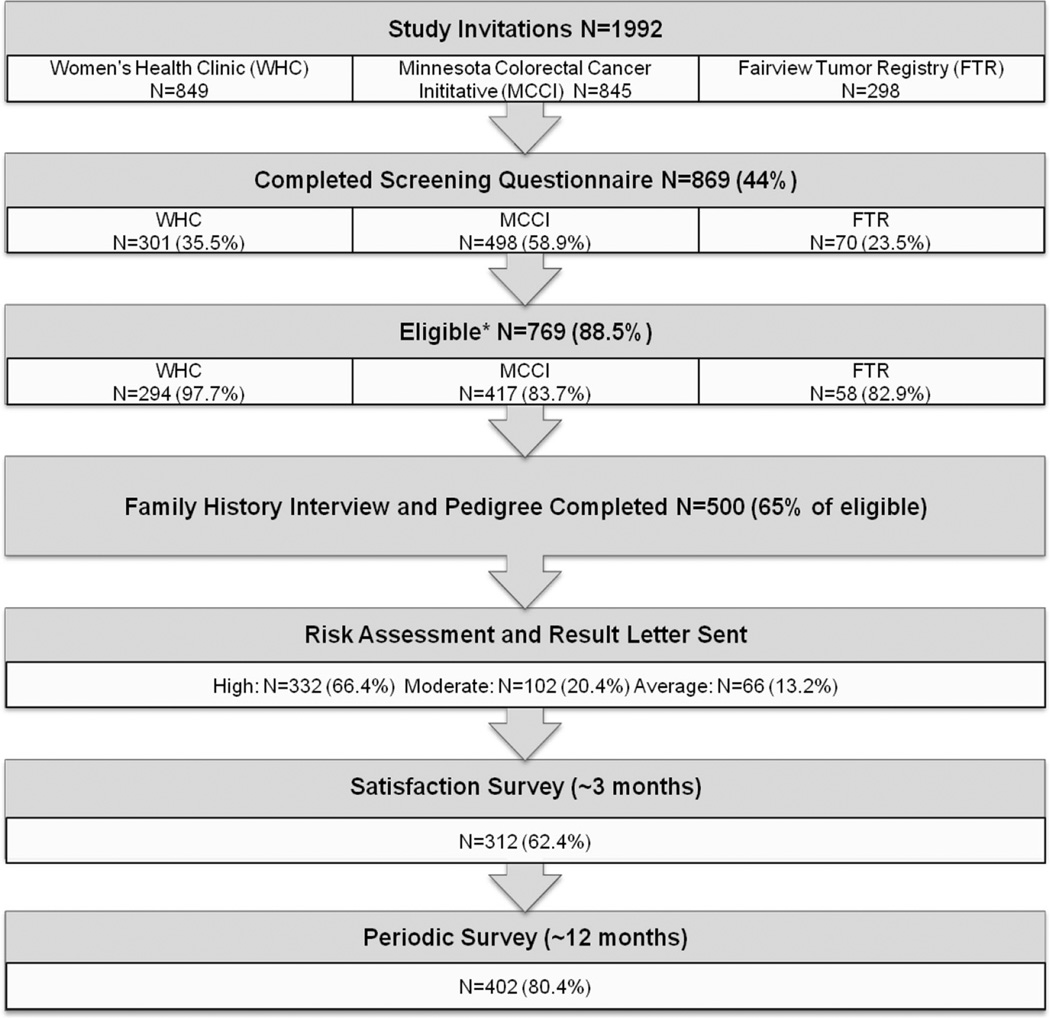

The Bernstein Registry and this study were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. The study included seven steps: (1) mailed invitation; (2) screening eligibility questionnaire; (3) consent and telephone family history interview; (4) risk assessment; (5) mailed result letter including pedigree and recommendations/information on genetic counseling; (6) mailed satisfaction survey 3 months after receipt of risk result letter and (7) mailed follow-up survey 1 year after receipt of risk results and recommendations regarding genetic counseling (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Registry schema and risk assessment results: participants, based on recruitment source, with completed family histories were assessed for familial cancer risk based on modified criteria from Hampel et al. [30]. *≥1 risk factor on screening questionnaire

Invitation and screening questionnaire

The 7-item screening eligibility questionnaire was mailed along with an invitation letter. The invitation letter was either signed by a clinic physician (WHC) or the Director of the previous research or clinical registry (MCCI and FTR). The questionnaire was developed based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network-published familial risk assessment guidelines and clinical genetic counselor expertise [25, 26]. The purpose of the questionnaire was to identify participants likely to be at increased risk of cancer based on family history. The questionnaire was piloted in 15 cases previously assessed for hereditary cancer risk from the prior MCCI registry and 20 patients referred to the University of Minnesota Familial Cancer Clinic and familial cancer risk was assessed independently by the genetic counselor. Once edited, concordance was 100 % between questionnaire values (increased risk versus not increased risk) and genetic counselor-led risk assessment for both test groups. Any participant with at least one “yes” response on the screening questionnaires was considered at “increased familial risk” and eligible for subsequent participation in the Bernstein Registry.

Family history interview

Participants with potential increased risk based on screening questionnaires were consented and a telephone interview appointment scheduled. Participants were mailed a preparatory packet of materials. The telephone interview tool was designed by review of existing family history collection tools [27–29]. The format was developed based on the form used by the San Diego Colon Cancer Family Registry (http://epi.grants.cancer.gov/CFR/about_colon.html) with permission of the developers. Interviewers were trained by study staff experienced at collecting family history through several previous studies. These interviewers collected family history information including all first, second and third-degree relatives’ ages or age at death, cancer diagnoses and age at cancer diagnosis using the devised scripted interview form. Interview data were recorded manually, coded and independently reviewed by a second trained interviewer for accuracy.

Risk assessment

Based on self-reported family history, four-generation pedigrees were prepared electronically (http://www.progenygenetics.com/). The first 50 pedigrees were independently assessed by two board-certified genetic counselors and, due to the high degree of concordance, thereafter by at least one genetic counselor. For the HCS risk assessment analysis portion of the study, “Hampel criteria” were used for assessment [30]. The criteria selection was based on the following: (1) they were supported by a review of the risk assessment literature to that date; (2) they could be used on patient-provided family history information without data from medical records; (3) they could be assessed for nearly all potential HCS or associations; and (4) they were validated [30]. An updated version of these HCS risk assessment and referral criteria has recently been published [8]. Since the current referral guidelines were not available at the time of the study, subject risk assessment and referral patterns differ from updated guidelines.

Following risk assessment, a letter was then sent to participants summarizing their cancer risk level (high, moderate or average based on the “Hampel Criteria”), the syndrome/cancer risk description, and if appropriate, a recommendation for pursuit of genetic counseling. A copy of the family pedigree was included along with instructions on how to read the pedigree. Additionally, high risk level assessment letters included information about the availability and advisability of utilizing genetics services, a contact list of local genetic service providers, current NCCN management guidelines (as appropriate) and an explanation of the purpose of genetic counseling were provided.

Satisfaction survey

A follow-up survey was mailed approximately 3 months after the risk assessment letter. Using a four-point Likert scale from “not helpful” to “very helpful”, the survey addressed subjects’ satisfaction with the following items: invitation materials, preparation materials for family history interview, interviewer, pedigree, and risk assessment letter. An additional question addressed participant information sharing: “Did you share your information with anyone?” Respondents were asked to indicate who they shared the information with: family member who lives with you, family members not in household, personal physician/ primary care provider, genetic counselor, other health care provider (specified) and other. The phrasing of this question recognized that genetic counseling appointments may be difficult, in some cases, to obtain in the three elapsed months. However, this question provided information about whether the participant recognized the utility of sharing the information with relevant individuals, including medical providers.

Follow-up survey

A follow-up survey was mailed 1 year from receipt of risk information to ascertain uptake of genetic counseling and testing. Alternative contact information was also requested in order to allow re-contact as necessary.

Statistical methods

Demographics, cancer family history, and hereditary cancer risk assessments were summarized for participants and compared by recruiting clinic using Chi squared and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Items related to satisfaction with participation in the registry were summarized. Number of respondents, relative frequencies, means and standard deviations (SD) are reported. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Screening questionnaire

A total of 1992 invitations to participate were sent to individuals in the WHC, MCCI and FTR cohorts (Fig. 1). Of these, 869 subjects (44 %) agreed to participate by completing the mailed screener. Based on the screener, 769 (88.5 %) were eligible for enrollment into the registry because one or more family history factors indicated an increased risk for hereditary cancers. Of the 769 eligible subjects, 500 (65.0 %) completed the family history interview.

Table 1 outlines the demographic distribution of the participant population across the three clinics. As would be expected from the nature of the relevant cancers, the participants differed significantly by clinic patient population in terms of age (p < 0.0001), sex (p < 0.0001), and personal history of cancers (all p < 0.01). The mean age of participants was 60 ± 12.7 years and the majority were female (82.0 %). As a result of the clinic patient sources, a greater number were at increased risk of an HCS—e.g., early-onset disease, known cancer diagnosis, or family history than would be expected in the population at large.

Table 1.

Description of participants completing family history interview, by clinic

| Overall |

WCC |

MCC |

FTR |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age | 500 | 60.0 (12.7) | 184 | 55.0 (12.9) | 284 | 62.2 (11.7) | 32 | 70.2 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| N | % | N | %N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Female | 410 | 82.0 | 184 | 100.0 | 194 | 68.3 | 32 | 100.0 | |

| Male | 90 | 18.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 90 | 31.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| History of cancer of colon, rectum , breast, pancreas, uterus, or stomach at <50 yearsa | |||||||||

| Personal | 123 | 25.4 | 61 | 36.1 | 58 | 20.4 | 4 | 12.5 | 0.0002 |

| Relative | 283 | 63.0 | 86 | 55.5 | 185 | 69.0 | 12 | 46.2 | 0.004 |

| History of breast cancer <50 yearsa | |||||||||

| Personal | 71 | 14.6 | 24 | 14.0 | 17 | 6.0 | 30 | 96.8 | <0.0001 |

| Relative | 224 | 51.0 | 84 | 53.9 | 117 | 46.1 | 23 | 79.3 | 0.002 |

| History of ovarian cancer, FT, PP at any agea | |||||||||

| Personal | 101 | 20.8 | 94 | 55.3 | 6 | 2.1 | 1 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Relative | 111 | 27.5 | 44 | 32.1 | 59 | 24.6 | 8 | 29.6 | 0.28 |

| History of 2 or more cancersa | |||||||||

| Personal | 89 | 18.3 | 57 | 33.3 | 27 | 9.5 | 5 | 15.6 | <0.0001 |

| Relative | 193 | 47.1 | 58 | 43.0 | 123 | 49.6 | 12 | 44.4 | 0.44 |

| History of >10 colon or rectal polypsa | |||||||||

| Personal | 48 | 10.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 43 | 15.9 | 4 | 12.9 | <0.0001 |

| Relative | 97 | 37.3 | 15 | 15.8 | 79 | 52.7 | 3 | 20.0 | <0.001 |

Participants with missing data or who reported “Don’t Know” are not included in the denominator when calculating percent

Risk assessment

Upon review by the genetic counselor, 332 (66.4 %) subjects were found to be at high risk for one or more HCS, 102 (20.4 %) were at increased or “moderate” for one or more type of cancer, and 66 (13.2 %) had no sign of elevated risk and were categorized as “average” cancer risk (Table 2). Of note, participants could score in more than one category (i.e. high for one cancer and moderate for another cancer). Average risk implies the subject did not score high or moderate for any category and is at general population risk for cancer. The most commonly identified HCS risk was for colon cancer and next most common was breast-ovarian cancer. Participants from the WHC and MCCI cohorts were more likely to be high or moderate risk than those from the FTR (p = 0.03).

Table 2.

Detailed hereditary cancer risk assessment results by clinic

| Overall |

WCC |

MCC |

FTR |

p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | ||

| Hereditary cancer risk assessment | 0.03 | ||||||||

| High/known mutation | 332 | 66.4 | 120 | 65.2 | 194 | 68.3 | 18 | 56.3 | |

| Moderate | 102 | 20.4 | 41 | 22.3 | 57 | 20.1 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Average | 66 | 13.2 | 23 | 12.5 | 33 | 11.6 | 10 | 31.3 | |

| High risk | |||||||||

| Breast-ovarian (non-Ashkenazi Jewish) | 124 | 24.8 | 67 | 36.4 | 44 | 15.5 | 13 | 40.6 | <0.0001 |

| Breast-ovarian (Ashkenazi Jewish) | 6 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.61 |

| Breast (Ashkenazi Jewish) | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.64 |

| Ovarian (Ashkenazi Jewish) | 4 | 0.8 | 3 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.47 |

| Colon/HNPCC | 168 | 33.6 | 32 | 17.4 | 134 | 47.2 | 2 | 6.3 | <0.0001 |

| Prostate | 6 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 6.3 | 0.04 |

| Lung | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.43 |

| Melanoma | 6 | 1.2 | 4 | 2.2 | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.38 |

| Stomach | 3 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 3.1 | 0.23 |

| Li-Fraumeni | 5 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 6.3 | 0.05 |

| MEN1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| MEN2/thyroid | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.64 |

| Cluster (all)b | 19 | 3.8 | 7 | 3.8 | 9 | 3.2 | 3 | 9.4 | 0.20 |

| Known mutation/clinical diagnosisc | 55 | 11.0 | 23 | 12.5 | 32 | 11.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.08 |

| Moderate risk | |||||||||

| Ovarian (non-Ashkenazi Jewish) | 59 | 11.8 | 52 | 28.3 | 7 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.0001 |

| Breast (non-Ashkenazi Jewish) | 4 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.00 |

| Colon | 70 | 14.0 | 5 | 2.7 | 60 | 21.1 | 5 | 15.6 | <0.0001 |

| Polyposisd | 59 | 11.8 | 12 | 6.5 | 47 | 16.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0003 |

| Prostate | 8 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 1.4 | 3 | 9.4 | 0.01 |

| Melanoma | 21 | 4.2 | 6 | 3.3 | 10 | 3.5 | 5 | 15.6 | 0.02 |

| Thyroid | 5 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 3.1 | 0.31 |

Percent of total patients with risk assessment (500)

High risk cluster includes ≥3 cases of (in one lineage): bladder, brain, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, lung, mouth or throat, multiple myeloma, pancreatic, sarcoma, other skin cancer, testicular, hematological malignancies (in first or second degree relatives)

A category created for participants reporting genetic testing results and/or a known hereditary cancer syndrome which would place subject in high risk category regardless of family history

Polyposis defined as a moderate risk category (modification to existing criteria)

Satisfaction survey

Of the 500 enrolled participants, 312 (62.4 %) returned the satisfaction survey. The time interval between the subject’s receipt of the risk assessment letter with recommendations for pursuit of genetic counseling and the return of the satisfaction survey averaged 4.8 months (range 3–16 months). Of all follow-up respondents, 98.4 % (307/ 312) found the letter explaining their cancer risk and recommendations for pursuit of genetic counseling to be at least “somewhat helpful” (Table 3). A total of 229 (73.4 %) reported sharing the provided information regarding their cancer risk with someone: family members (51.1 %), healthcare provider (18.8 %) and/or genetic counselor (5.7 %).

Table 3.

Results of 3-month satisfaction survey (N = 312)

| Very helpful |

Helpful |

Somewhat helpful |

Not helpful |

Did not answer |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Invitation materials about registry | 139 | 44.6 | 154 | 49.4 | 14 | 4.5 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Materials for preparation for family history interview | 150 | 48.1 | 139 | 44.6 | 17 | 5.5 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Family history interviewer | 205 | 65.7 | 93 | 29.8 | 9 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Family tree | 149 | 47.8 | 125 | 40.1 | 29 | 9.3 | 8 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Letter explaining cancer risk | 128 | 41.0 | 133 | 42.6 | 36 | 11.5 | 7 | 2.2 | 8 | 2.6 |

Follow-up survey

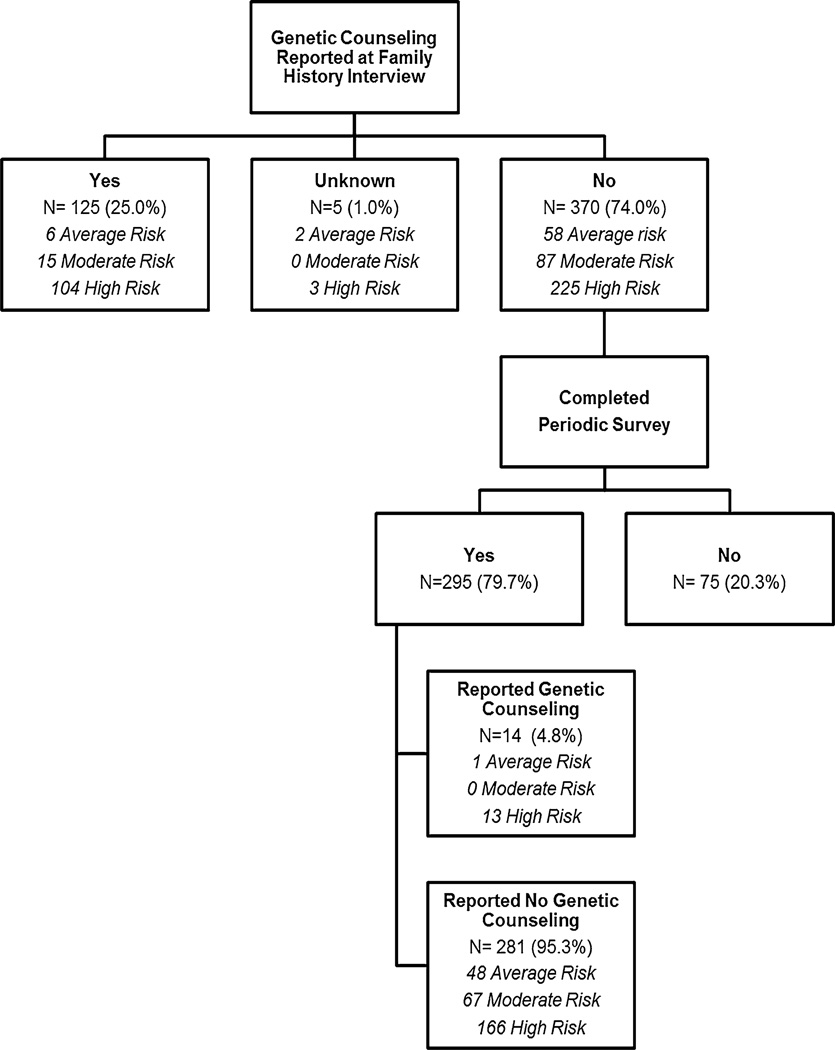

Among all participants who completed the family history interview, 402 (80.4 %) completed the follow-up survey an average of 23 months (range 12–34) following the initial risk assessment letter. Prior to risk assessment, 125 subjects reported previously having genetic counseling with a remaining 370 reporting no genetic counseling experience (Fig. 2). Analysis was performed on those without previous genetic counseling in order to assess the uptake of genetic counseling. Of the 370 without previous genetic counseling, 295 (79.7 %) returned the follow-up survey. Of the 179 “High risk” respondents without previous genetic counseling, only an additional 13 (7.3 %) complied with the risk assessment letter recommendation and pursued genetic counseling. Thus, the majority of participants who received a recommendation to have genetic counseling did not make appointments during an approximate 2-year follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Genetic counseling recommendation uptake (≥12 months from recommendation letter)

Discussion

In 2005, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that women with family history factors indicating an increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer be referred for genetic services. By 2015 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society for Clinical Oncology, as well as several other consensus groups, confirmed the need to identify people with a hereditary cancer risk who would benefit from referral for genetic counseling. This study outlines the results of a process for screening for hereditary cancer based on reported patient family history.

Overall, several points arise from the results of this study: (1) populations enriched for hereditary cancer risk are willing to participate in a hereditary cancer risk assessment program; (2) a significant number of cancer patients or patients with family history of cancer carry familial factors that increase their risk of cancer; and (3) despite willingness to participate in research, few participants informed of their increased hereditary risk of cancer pursue genetic counseling when the sole intervention is a letter describing the increased risk and providing recommendations and information on genetic counseling.

Familial cancer registry experience

Since many genetics research studies are dependent on large population pools with matched family history data, it is vital that registries exist to further future genetics research. For this reason, both in-house and multi-center registries have been developed including the Colon and Breast Cancer Family Registries. With the expansion of cancer genetic counseling services and increased knowledge of cancer genetic counseling and testing on the part of medical institutions, providers, and patients, it is important outline the process of development of a successful registry. We found that a significant number of at-risk patients agreed to participate in our risk assessment program with an uptake rate of 52.8 %. Comparatively, use of a similar tool, “Health Heritage” found only a 9.5 % return rate in a primary care population and 17.7 % uptake rate in a recruited population [31]. Another tool, “Family Health-ware” had a 19 % overall recruitment rate [28]. It is presumed that the favorable recruitment of our study may be due to the fact that our study pool was enriched for cancer patients and previous study participants, both highly motivated at-risk populations.

The response rates for the satisfaction and follow-up surveys in the registry participants remained high (62.4 and 80.4 %, respectively) over time suggesting a strong degree of commitment to research participation and involvement in the registry. The participants reported satisfaction as well with the process including 98.4 % of subjects finding the letter and recommendation at least “somewhat helpful” or better. This suggests that development of familial cancer registries is feasible and that retention of subjects is possible. Given the high rate of increased familial cancer risk (88.5 % of participants) in this study, it suggests that motivated patients can be a rich resource for development of familial cancer registries.

Future considerations

While not a focus or specific aim of the Bernstein Registry study, low uptake of recommendation of genetic counseling was identified. Following the characterization of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in 1994 and 1995, respectively, several studies documented high predicted uptake rates for genetic testing in these research cohorts [32–34]. Over time, genetic testing has become more firmly entrenched in clinical care as hereditary cancer risks were quantified, tests improved and management and treatment regimens codified. However, the actual uptake rates for genetic testing have consistently fallen below original predicted rates [35]. Uptake of genetic counseling itself and/or genetic risk assessment has been less extensively studied; however; findings also suggest a reduced uptake rate of these services [36, 37].

In the literature, very limited data exist regarding uptake rates for genetic counseling, especially when differentiated from genetic testing. A recent study evaluating the efficacy of an online risk assessment program found that if those with genetic counseling recommendations were referred by their providers, only 21 % attended a genetic counseling session [38]. Similar to our findings, another study using a letter of referral for genetic counseling from the treating physician did not appear to strongly influence patients’ decisions to pursue genetic counseling [37, 39]. Literature on behavioral change suggests that there are multiple discrete stages of change and that perhaps stage-based appeals which address where a patient is in the decision-making process may increase the acceptance rate of genetic counseling [40]. Future research on reasons for the low uptake of recommended genetic counseling services is an interesting subject deserving of in-depth research and thus is under preparation as separate research question.

On-going use of the registry is another future consideration and one which will require use of up-to-date risk assessment tools. Since the original development of the study, the “Hampel Criteria” have been updated and published by a joint commission of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors [8]. Also, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated the Genetic/ Familial High Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian and has added the Genetic/Familial High Risk Assessment: Colorectal. The expansion of these guidelines to include several other cancer syndromes beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2 has made these guidelines more useful in comprehensive identification of hereditary cancer syndromes. Application of these current guidelines and/or other guidelines to the family histories in the Bernstein Registry would change the risk assessment, in some cases. For example, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology in October 2014 recommended that all epithelial ovarian, peritoneal and fallopian tube cancer patients be referred for genetic counseling and consideration of genetic testing regardless of family history (www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/guidelines/genetic-testing-for-ovarian-cancer/). This is a stronger statement than the “moderate risk” category typically assigned to these patients in the original criteria. It is recognized that future registries and studies would be developed using these updated criteria.

This report of the Bernstein Registry outlines the development of a successful familial cancer registry and provides several avenues for future research and refinement.

Conclusion

A patient-directed familial cancer risk assessment process was developed and evaluated in a study population enriched for hereditary cancer risk. Participation and satisfaction in the process were high; however, pursuit of genetic counseling services was limited, even in this high risk population. Future studies, utilizing updated criteria and tailored to stages of decision-making, would clarify the most effective means to ensure needed genetic information is received and utilized by families at greatest risk of hereditary cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Health Studies Section of the University of Minnesota, School of Public Health for the data acquisition and management services as well as Kristin Oehlke, M.S., C.G.C. and members of the William C. Bernstein, M.D. Familial Cancer Registry advisory board who provided expertise in preparation of the original study design and execution. This study was funded by the William C. Bernstein, M.D. Grant and the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- HCS

Hereditary cancer syndrome

- WHC

Women’s Health Clinic

- FTR

Fairview Tumor Registry

- MCCI

Minnesota Colorectal Cancer Initiative

Footnotes

Author contributions K.B.N.: Primary study design, data collection, risk assessment of subjects and writing. M.G.: Provision of subjects, manuscript editing, study design committee member. R.I.V.: Statistician, results and figure development, manuscript reviewer. T.C.: Co-Primary Investigator and study design committee member. A.L.: Study design, risk assessment analysis, author of methods section. A.B.: Risk assessment of subjects, QA checking of risk assessments. R.D.M.: Principal Investigator, study development, manuscript editing. All authors read and approved final manuscript.

References

- 1.Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):151–161. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2143–2153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharoah PD, Antoniou A, Bobrow M, Zimmern RL, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat Genet. 2002;31(1):33–36. doi: 10.1038/ng853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed 23 June 2016];Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian (Version 2.2016) 2016 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf.

- 5.Lu KH, Wood ME, Daniels M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Expert Statement: collection and use of a cancer family history for oncology providers. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):833–840. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(8):1025–1048. doi: 10.1097/DCR.000000000000000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hampel H. NCCN increases the emphasis on genetic/familial high-risk assessment in colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(5 Suppl):829–831. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, Pearlman R, Wiesner GL Guideline Development Group AeCoMGaGPPaGCaNSoGCPGC. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet Med. 2015;17(1):70–87. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoffel EM, Mangu PB, Gruber SB, et al. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline endorsement of the familial risk-colorectal cancer: European Society for Medical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(2):209–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyer VA, Force USPST. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):271–281. doi: 10.7326/M13-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qureshi N, Wilson B, Santaguida P, et al. Collection and use of cancer family history in primary care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;159:1–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheson LS, Wiesner GL, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Family history-taking in community family practice: implications for genetic screening. Genet Med. 2000;2(3):180–185. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood ME, Stockdale A, Flynn BS. Interviews with primary care physicians regarding taking and interpreting the cancer family history. Fam Pract. 2008;25(5):334–340. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frezzo TM, Rubinstein WS, Dunham D, Ormond KE. The genetic family history as a risk assessment tool in internal medicine. Genet Med. 2003;5(2):84–91. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000055197.23822.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brierley KL, Campfield D, Ducaine W, et al. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med. 2010;74(7):413–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overbeek LI, Hoogerbrugge N, van Krieken JH, et al. Most patients with colorectal tumors at young age do not visit a cancer genetics clinic. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(8):1249–1254. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9345-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer LA, Anderson ME, Lacour RA, et al. Evaluating women with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: missed opportunities. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):945–952. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da08d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Greene MH, Taplin S, Olson L, Freedman AN. Hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancer genetics knowledge in a national sample of US physicians. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10):749–755. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wideroff L, Garceau AO, Greene MH, et al. Coherence and completeness of population-based family cancer reports. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2010;19(3):799–810. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brannon Traxler L, Martin ML, Kerber AS, et al. Implementing a screening tool for identifying patients at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: a statewide initiative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(10):3342–3347. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlando LA, Wu RR, Beadles C, et al. Implementing family health history risk stratification in primary care: impact of guideline criteria on populations and resource demand. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C(1):24–33. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doerr M, Edelman E, Gabitzsch E, Eng C, Teng K. Formative evaluation of clinician experience with integrating family history-based clinical decision support into clinical practice. J Pers Med. 2014;4(2):115–136. doi: 10.3390/jpm4020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facio FM, Feero WG, Linn A, Oden N, Manickam K, Biesecker LG. Validation of My Family Health Portrait for six common heritable conditions. Genet Med. 2010;12(6):370–375. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e15bd5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulse NC, Ranade-Kharkar P, Post H, Wood GM, Williams MS, Haug PJ. Development and early usage patterns of a consumer-facing family health history tool. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:578–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(10):1060–1096. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engstrom PF, Arnoletti JP, Benson AB, 3rd, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: colon cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(8):778–831. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon PW, Scheuner MT, Jorgensen C, Khoury MJ. Developing Family Healthware, a family history screening tool to prevent common chronic diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(1):A33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Wang C, et al. Familial risk for common diseases in primary care: the Family Healthware Impact Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(6):506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweet KM, Bradley TL, Westman JA. Identification and referral of families at high risk for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):528–537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hampel H, Sweet K, Westman JA, Offit K, Eng C. Referral for cancer genetics consultation: a review and compilation of risk assessment criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41(2):81–91. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohn WF, Ropka ME, Pelletier SL, et al. Health Heritage(c) a web-based tool for the collection and assessment of family health history: initial user experience and analytic validity. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13(7–8):477–491. doi: 10.1159/000294415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman LS, Ostermeyer EA, Szabo CI, et al. Confirmation of BRCA1 by analysis of germline mutations linked to breast and ovarian cancer in ten families. Nat Genet. 1994;8(4):399–404. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378(6559):789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lerman C, Seay J, Balshem A, Audrain J. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of breast cancer patients. Am J Med Genet. 1995;57(3):385–392. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320570304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks L, Lennard F, Shenton A, et al. BRCA1/2 predictive testing: a study of uptake in two centres. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12(8):654–662. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakefield CE, Ratnayake P, Meiser B, et al. “For all my family’s sake, I should go and find out”: an Australian report on genetic counseling and testing uptake in individuals at high risk of breast and/or ovarian cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2011;15(6):379–385. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Miree CA, Brzosowicz J, Carter B, Laronga C. Recall of and reactions to a surgeon referral letter for BRCA genetic counseling among high-risk breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(7):1973–1981. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buchanan AH, Christianson CA, Himmel T, et al. Use of a patient-entered family health history tool with decision support in primary care: impact of identification of increased risk patients on genetic counseling attendance. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(1):179–188. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakefield CE, Ratnayake P, Meiser B, et al. “For all my family’s sake, I should go and find out”: an Australian report on genetic counseling and testing uptake in individuals at high risk of breast and/or ovarian cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2011;15(6):379–385. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neill SM, Peters JA, Vogel VG, Feingold E, Rubinstein WS. Referral to cancer genetic counseling: are there stages of readiness? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C(4):221–231. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]