Abstract

Disease relapse or progression is a major cause of death following umbilical cord blood (UCB) transplantation (UCBT) in patients with high-risk, relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Adoptive transfer of donor-derived T cells modified to express a tumor-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) may eradicate persistent disease after transplantation. Such therapy has not been available to UCBT recipients, however, due to the low numbers of available UCB T cells and the limited capacity for ex vivo expansion of cytolytic cells. We have developed a novel strategy to expand UCB T cells to clinically relevant numbers in the context of exogenous cytokines. UCB-derived T cells cultured with interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-15 generated >150-fold expansion with a unique central memory/effector phenotype. Moreover, UCB T cells were modified to both express the CD19-specific CAR, 1928z, and secrete IL-12. 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells retained a central memory-effector phenotype and had increased antitumor efficacy in vitro. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells resulted in significantly enhanced survival of CD19+ tumor-bearing SCID-Beige mice. Clinical translation of CAR-modified UCB T cells could augment the graft-versus-leukemia effect after UCBT and thus further improve disease-free survival of transplant patients with B-cell ALL.

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the standard of care in therapy for many patients with high risk or relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Unfortunately, many patients do not have suitable human leukocyte antigen-matched and readily available adult donors. umbilical cord blood (UCB) transplantation (UCBT) is a viable treatment alternative for these patients with the advantages of rapid graft availability, flexibility of scheduling and a reduced stringency of required (human leukocyte antigen) match.1,2 UCBT has also been associated with relatively low rates of leukemic relapse likely related to a robust graft-versus-leukemia effect.2–5 However, relapse remains a significant cause of treatment failure. In the adult series reported by Marks et al.,6 for example, the 3-year relapse incidence was 22% in 116 ALL UCBT recipients transplanted in first or second complete remission. Moreover, the relapse risk is considerably increased in patients transplanted with residual disease and in recipients of reduced-intensity conditioning. For these reasons there is a need to enhance the antileukemic efficacy of UCBT for B-cell ALL.

Expression of a tumor-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) allows for the generation of tumor-targeted T cells that are capable of non-major histocompatibility-restricted tumor recognition and eradication. T cells modified to express CD19-specific CARs can mediate effective antitumor responses both in vitro and in vivo in multiple murine models.7,8 In addition, early clinical trials utilizing T cells modified with a CD19-specific CAR have demonstrated significant antitumor efficacy in patients with CD19+ B-cell malignancies.9–12 Adoptive transfer of donor-derived CD19-specific CAR T cells can eradicate tumor persisting after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without evidence of graft-versus-host disease.13

Adoptive T-cell transfer therapy is also an attractive option in UCBT recipients to further augment graft-versus-leukemia effects, but is technically challenging due to the difficulty in generating sufficient numbers of effector T cells. Herein, we describe a novel technique to expand and genetically modify clinically meaningful numbers of UCB-derived CAR T cells. Expansion of UCB T cells in the context of interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-12 led to over 150-fold expansion and unique expression of both central memory markers and effector proteins, an ideal phenotype for adoptive cell transfer therapy. We then used retroviral transduction to generate UCB T cells expressing a CD19-specific CAR and an IL-12 transgene. This study demonstrates the feasibility of generating clinically relevant numbers of CAR UCB T cells that have effective antitumor efficacy in preclinical murine models. Our study supports the clinical translation of UCB-derived CAR T cells to further augment the graft-versus-leukemia potency of UCBT for B-cell ALL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

Raji (Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line) and Nalm6 (pre-B-cell ALL cell line) tumor cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 0.1 mm non-essential amino acids, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 5 × 10− 2 mm 2ME (Invitrogen). Retroviral producer cell lines (293 Glv9) producing 1928z, 1928z/IL-12, 4H1128z or 4H1128z/IL-12 encoding virus were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen). All media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 mm L-glutamine.

Isolation and expansion of T cells from UCB units

Fresh UCB units not meeting cell dose criteria for public banking were obtained from the Cleveland Cord Blood Center (Cleveland, OH, USA), and mononuclear cells were separated using density gradient centrifugation with Accu-prep (axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway). T cells were isolated, activated and expanded with Dynabeads ClinExVivo CD3/CD28 magnetic beads (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. UCB-derived T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 mm L-glutamine, in the presence of 100 IU/ml recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), 10 ng/ml recombinant human IL-12, 10 ng/ml recombinant human IL-7 or 10 ng/ml recombinant human IL-15 (all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Viable cells were enumerated using Trypan blue (Invitrogen) exclusion. Secondary stimulation was achieved with ClinExVivo CD3/CD28 beads at a bead to T-cell ratio of 1:2.

Retroviral transduction of UCB T cells

Activated UCB T cells were retrovirally transduced as previously described.14 Briefly, UCB T cells were spinoculated three times with retroviral supernatant on retronectin (Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) coated plates. Transduction efficiency was assessed by flow cytometry using goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE, Invitrogen) to detect 1928z or an Alexa-Fluor647 conjugated hamster antibody that specifically binds the 4H1128z CAR (Monoclonal Antibody Facility, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center).

Flow cytometric analysis

Expanded UCB T cells were analysed by flow cytometry after staining with the following antibodies according to the manufacturers instructions (clone numbers are shown): PE-conjugated antibodies specific for human CCR7 (3D12), Granzyme B (GB11), fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies specific for perforin (dG9), CD28 (CD28.2), CD107a (eBioH4A3), PD-1 (eBioJ105), CTLA-4 (14D3) and allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies specific for CD25 (BC96) and CD107a (ebio1D48), and PE-cyanine dye 7-conjugated antibody specific for IFNγ (4S.B3) obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). PE-conjugated antibodies specific for CD4 (S3.5) or CD45RA (MEM-56) and allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies specific for human CD8 (3B5) and CD62L (Dreg-56) were all obtained from Invitrogen. Intracellular staining (for cytokines and CTLA-4) was achieved using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Fixation/Permeabilization kit with BD GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, in combination with a fixable viability dye (efluor450, eBioscience). Proliferation of UCB T cells was achieved by labeling T cells with CellVue Claret Far Red Fluorescent cell linker mini kit (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled T cells were then incubated with Nalm6 tumor cells at 1:1 ratio overnight before flow cytometric analysis. Tumor cells were excluded from analysis by staining with allophycocyanin-conjugated antibody specific for CD19 (SJ25-C1, Invitrogen).

Cytotoxicity assays

The cytotoxic capacity of UCB-derived gene-modified T cells was assessed using a standard 51chromium (51Cr) assay, described elsewhere.15 Briefly, 51Cr-radiolabeled tumor cells were incubated with transduced UCB T cells at varying CAR+ effector T cell to target ratios. The amount of 51Cr released in the supernatant was measured using a Perkin Elmer Top Count NXT (Perkin Elmer, Irvine, CA, USA) and correlated with percentage-specific lysis.

Cytokine detection assays

UCB-derived T cells were co-cultured with Raji or Nalm6 tumor cells at a 1:1 CAR+ T-cell:tumor-cell ratio for 24 h. Supernatant was collected and cytokines were detected using a multiplex human cytokine detection assay (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were analyzed using the Luminex IS100 system and IS2.3 software.

In vivo SCID-Beige murine studies

Fox Chase CB17 (CB17.Cg-PrkdcscidLystbg-J/Crl, SCID-Beige mice; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) of 6–8 weeks of age were inoculated intravenously with 1 × 106 Nalm6 tumor cells, expressing a GFP-firefly luciferase fusion protein (Nalm6-eGFP-FFluc). The following day, mice received one systemic infusion of 5 × 106 CAR+ UCB-derived T cells. Mice were monitored for survival and were euthanized when showing signs of distress. All experiments were performed in accordance with an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol (protocol 00-05-065). Bioluminescent imaging was achieved using the Xenogen IVIS imaging system and analyzed with Living Image software (Xenogeny) as previously described.14 Briefly, tumor-bearing mice were injected intraperitoneally with d-Luciferin (150 mg/kg) and after 10 min were imaged under isofluorane anesthesia. Image acquisition was achieved using a 25 cm field of view, medium binning level and 60-s exposure time.

Statistical analyses

Survival data were assessed using a log-rank test. Flow cytometry and cytokine secretion data was analyzed using a Mann–Whitney test using Prism 5.0 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

UCB T-cell culture in IL-12 and IL-15 results in over 150-fold expansion and a unique memory/effector phenotype

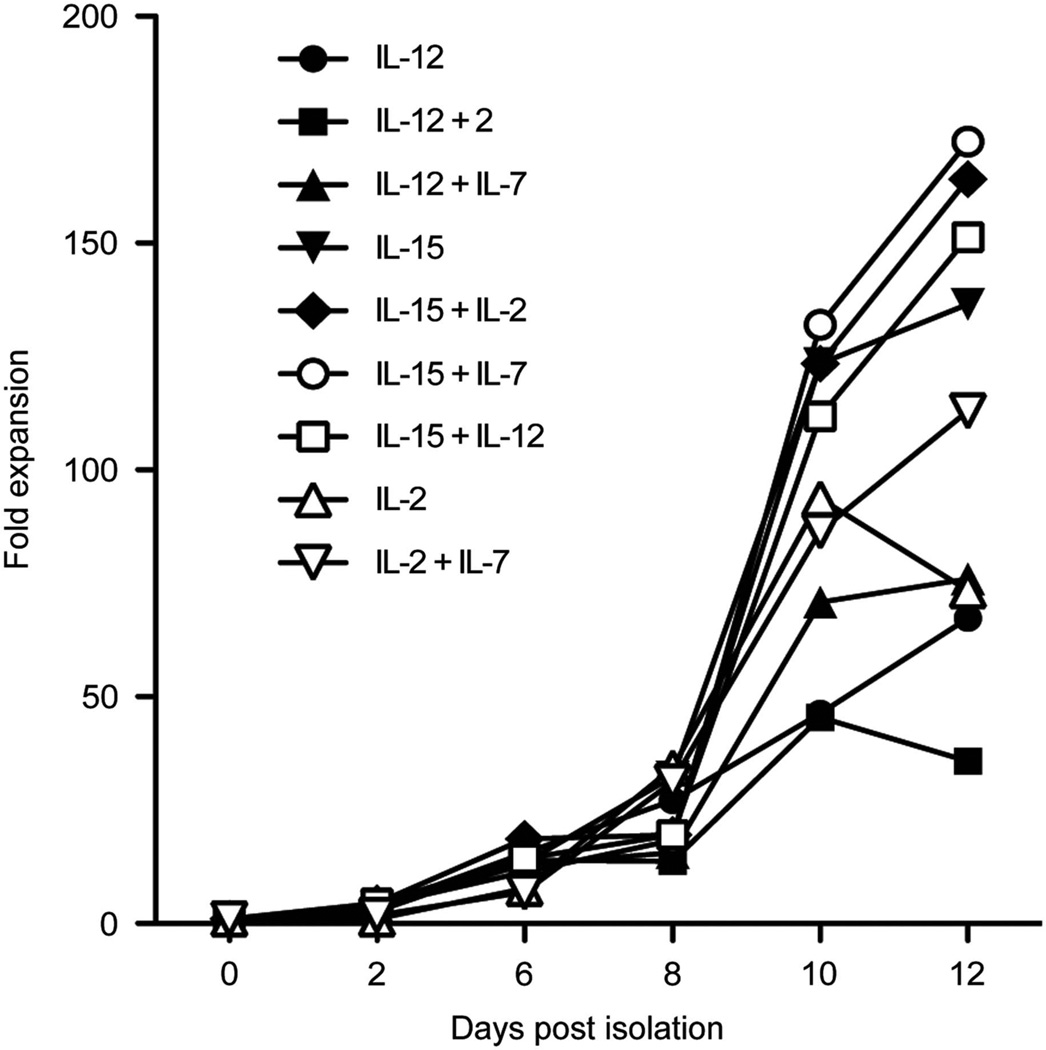

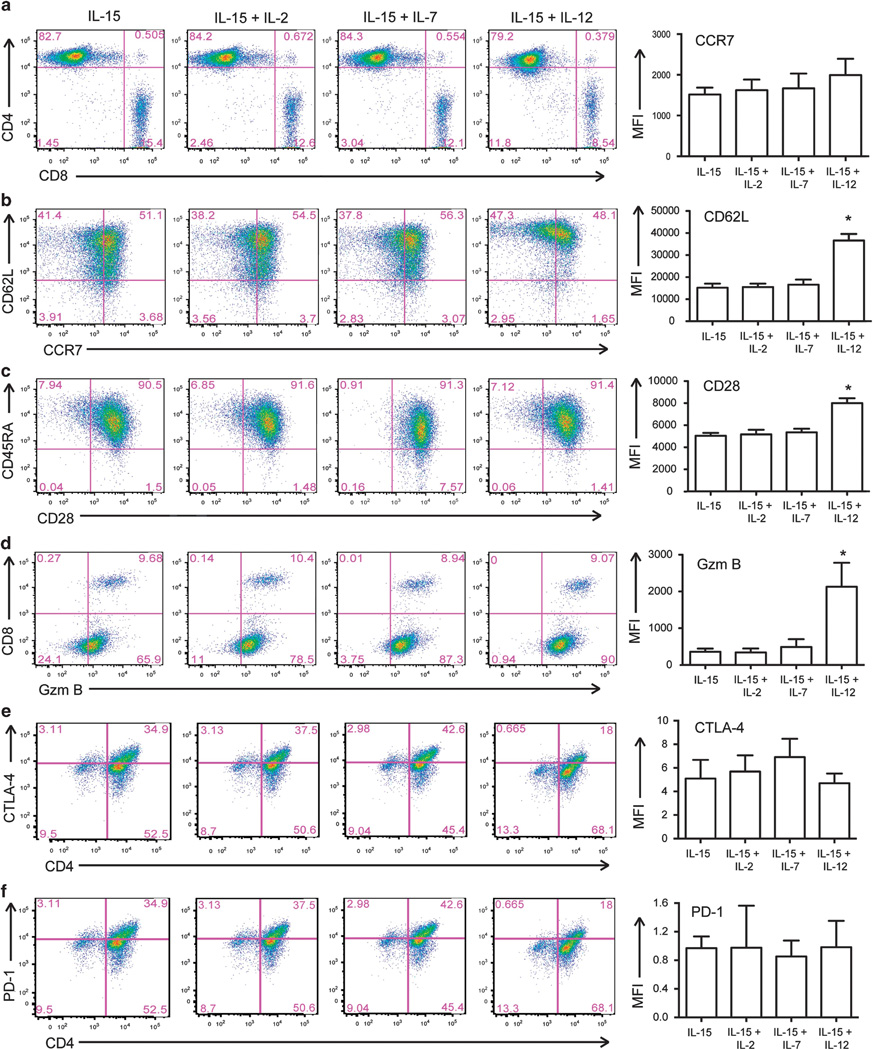

T lymphocytes can be successfully isolated from UCB units using CD3/CD28 beads.16 UCB T cells must be expanded a several fold for clinical relevance and adoptive cell transfer therapy. To investigate the optimal culture conditions for maximal expansion of CB derived T cells, we cultured activated UCB T cells in combinations of 10 ng/ml IL-12, IL-15, IL-7, and/or 100 IU/ml IL-2. By enumerating viable cells, we determined that culture in the context of IL-15 is important for the expansion of UCB T cells. Culture of UCB T cells in IL-12+IL-15, IL-15+IL-7, IL-15+IL-2 or IL-15 alone resulted in over 120-fold expansion (Figure 1) in a 12day period. Flow cytometry was used to determine the CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio and we demonstrated that UCB T cells expanded in these cytokine combinations had equivalent percentages of CD4 and CD8 T cells (Figure 2a). We then investigated the expression of memory markers on these cells, particularly CD62L and CCR7. IL-12 and IL-15 expanded UCB T cells had a higher expression of these markers compared to cells expanded in IL-15+IL-7, IL-15+IL-2 or IL-15 alone (Figure 2b). In addition, increased expression of CD28 in these cells was observed (Figure 2c), and cells expanded in IL-12 and IL-15 displayed increased expression of the cytotoxic effector protein, Granzyme B, in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2d). We also determined the expression of CTLA-4 and PD-1 on expanded UCB T cells to ensure that expansion did not result in anergy/exhaustion. There is no significant difference in expression of PD-1 or CTLA-4 on UCB T cells expanded in IL-15, IL-15+IL-2, IL-15+IL-7 or IL-15+IL-12 (Figures 2e and f). IL-12- and IL-15-expanded UCB T cells had a unique phenotype with increased expression of central memory markers which was seen alongside expression of cytotoxic effector proteins thereby combining central memory and effector T-cell phenotypes.

Figure 1.

Optimal expansion of CD3/CD28-activated UCB-derived T cells. UCB T cells were isolated and expanded with CD3/CD28 beads and cultured in the context of stimulatory cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15 or combinations thereof. Viable cells were enumerated and fold expansion of T cells was calculated. Results shown are the average fold expansion from 7–10 UCB units in independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Phenotype of IL-12 and IL-15-expanded UCB-derived T cells. The phenotype of UCB-derived T cells cultured in IL-15, IL-15+IL-2, IL-15 + IL-7 and IL-15+IL-12 was compared using flow cytometry. Representative plots show that UCB T cells expanded in IL-12 and IL-15 have similar ratios of CD4:CD8 T cells (a) and increased expression of CCR7 and CD62L (b), CD28 (c) and Granzyme B in both CD8 and CD4 T cells (d). There is no difference in expression of CTLA-4 (e) or PD-1 (f) in UCB T cells expanded in IL-15, IL-15+IL-2, IL-15+ IL-7 or IL-15+IL-12. Mean fluorescence intensity of staining is from 3–4 independent experiments, *P < 0.05.

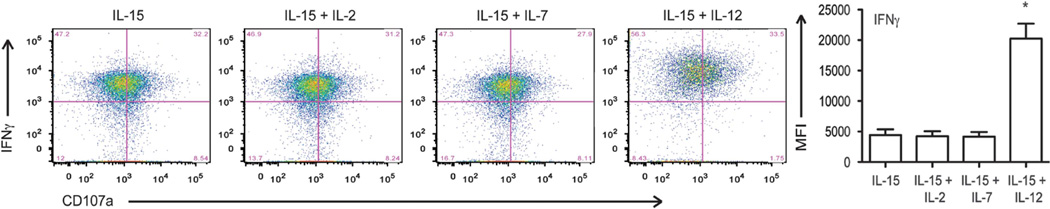

We then assessed the functional capacity of UCB T cells using intracellular staining and flow cytometry. UCB T cells expanded in IL-12 and IL-15 demonstrated increased production of IFN-γ following secondary stimulation compared to UCB T cells expanded in IL-15+IL-7, IL-15+IL-2 or IL-15 alone (Figure 3). These cells also trended toward increased CD107a expression, indicating increased cytotoxic capacity, although this was not statistically significant (Figure 3). From these studies, we conclude that culture of UCB T cells in the context of exogenous IL-12 and IL-15 supports maximal expansion of UCB T cells and a combined central memory/effector T-cell phenotype, ideal for adoptive cell therapy.

Figure 3.

Increased function of IL-12 and IL-15-expanded UCB-derived T cells. The function of UCB T cells expanded in IL-15, IL-15+IL-2, IL-15 +IL-7 or IL-15+IL-12 was determined by multiparameter flow cytometry following restimulation with CD3/CD28 beads. Representative plots show that UCB T cells cultured in IL-12 and IL-15 have increased production of IFNγ and a trend toward increased CD107a expression, a marker of degranulation. Data shown are representative of four independent experiments, *P < 0.05.

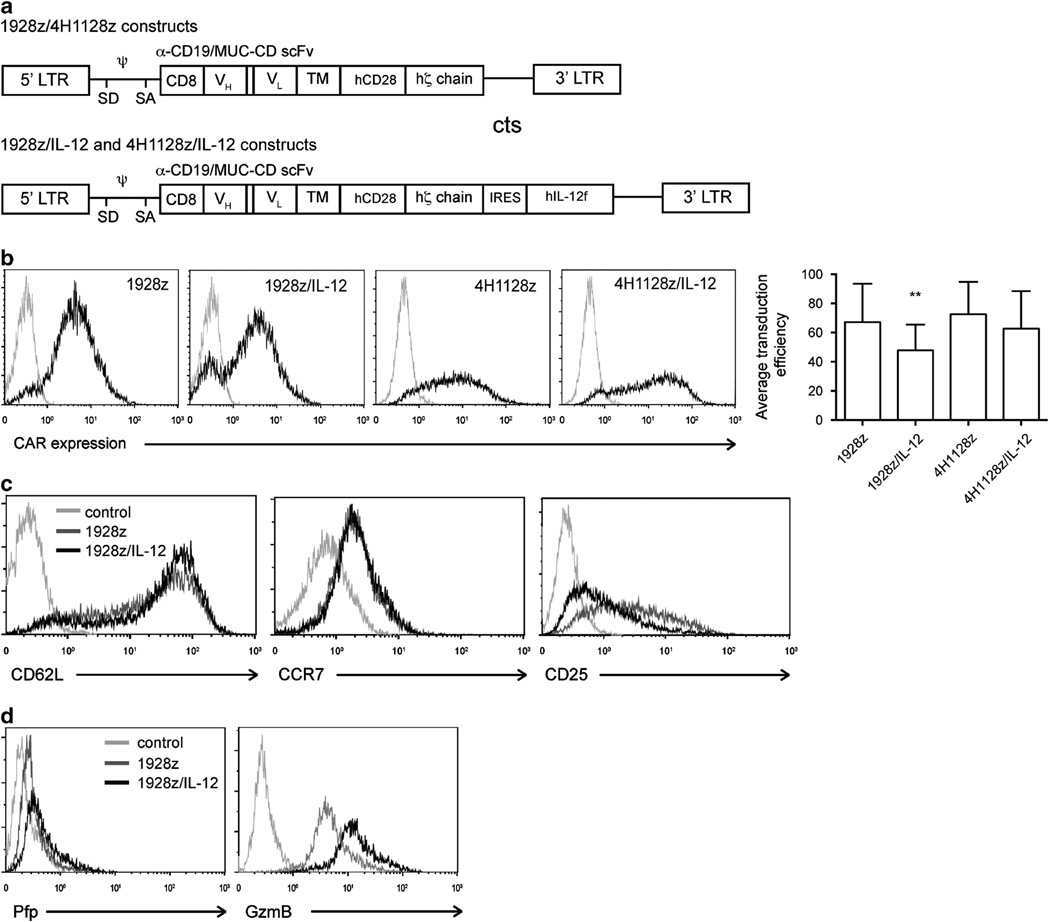

UCB-derived T cells can be effectively targeted to tumor with a CD19-specific CAR and IL-12 transgene

Meaningful adoptive therapy with UCB T cells requires improved antitumor efficacy. To address this challenge, we targeted UCB T cells to tumors with a CAR. The CAR consisted of an antibody recognition domain (specific for CD19 for 1928z or the control ovarian carcinoma antigen, MUC-16, for 4H11) linked to the CD28 and the CD3 zeta signaling domains (Figure 4a), as previously reported.7 Given the favorable effects of IL-12 on UCB T-cell phenotype and function described above, and previous studies in our laboratory demonstrating that IL-12 enhances T-cell mediated antitumor effects,17 we also modified UCB T cells with a vector encoding both the CAR and a flexi human IL-12 fusion protein.17 Following retroviral transduction of expanded UCB T cells, flow cytometry was used to detect CAR expression. UCB T cells transduced with 1928z, 1928z/IL-12, 4H1128z or 4H1128z/IL-12 expressed the chimeric receptor at reproducible levels (Figure 4b). The mean transduction from seven experiments (SEM) for UCB T cells transduced with 1928z was 67.24% (9.90), with 1928z/IL-12 was 47.7% (6.72), with 4H1128z was 75.52% (12.86) and with 4H1128z/IL-12 was 62.66% (10.49). Consistent with previous finding in murine T cells,17 expression of the CAR and IL-12 resulted in maintaining high CD62L and low CD25 expression compared to 1928z UCB T cells. However these cell types had equivalent expression of CCR7 (Figure 4c), as determined by flow cytometry.17 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells had increased production of both Granzyme B and perforin compared to cells expressing the CAR alone (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Expression of CD19-targeted CAR and IL-12 in UCB-derived T cells. UCB T cells cultured in IL-12 and IL-15 were modified to express the 1928z or control 4H1128z CAR with or without IL-12. (a) Schematic of constructs depicting the 5’ and 3’ long terminal repeats (LTR), splice donor (SD), splice acceptor (SA), packaging element (ψ), CD8 leader sequence (CD8), variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains of the single-chain variable fragment (scFv), transmembrane domain (TM), human CD28 signaling domain (hCD28), human zeta chain signaling domain (hζ chain) and flexi human IL-12 (hIL-12f). (b) Transduced UCB T cells expressed either 1928z or 4H1128z CAR following retroviral transduction, as determined by flow cytometry. Average transduction efficiency ± s.e.m. from seven experiments is shown, **P>0.05 (c) 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells showed increased expression of CD62L, equivalent CCR7 and decreased CD25 when compared to cells transduced with 1928z CAR alone, as determined by flow cytometry. (d) Expression of 1928z/IL-12 resulted in increased expression of Perforin (Pfp) and Granzyme B (GzmB) when compared to cells transduced with 1928z CAR alone, as determined by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of five independent experiments.

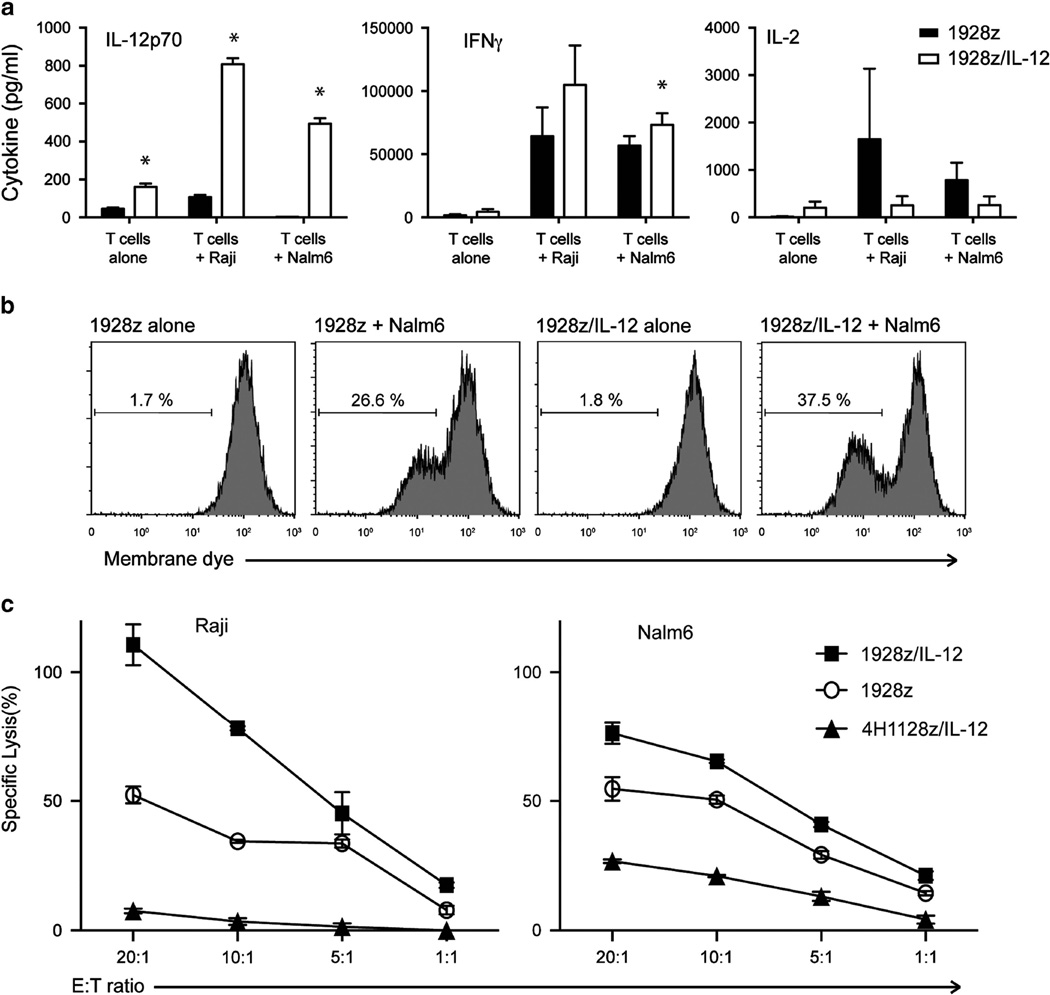

We then sought to determine the in vitro antitumor function of transduced UCB T cells. We utilized Luminex technology to measure UCB T-cell cytokine release following a 24-h coculture with Nalm6 or Raji tumor cells. 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells produced significant levels of IL-12 compared to control UCB T cells expressing the CAR alone (Figure 5a). In addition, 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells secreted increased levels of IFNγ in response to Raji and Nalm6 tumor cells, compared to 1928z UCB T cells (Figure 5a). Consistent with previous findings in murine T cells,17 we found 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells secreted decreased levels of IL-2 compared to 1928z UCB T cells following coculture with tumor (Figure 5a). We investigated T-cell proliferation using membrane-dye dilution assay and a 24 h coculture with Nalm6 tumor cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells exhibited enhanced proliferation compared to 1928z UCB T cells (Figure 5b). To determine the cytolytic capacity of transduced UCB T cells, we performed a 51Cr release assay and demonstrated that 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells mediated increased lysis of Raji and Nalm6 tumor cells compared to 1928z UCB T cells (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

UCB T cells modified to express both the 1928z CAR and IL-12 have increased proliferation and IFNγ in response to Nalm6 tumor cells. The ability of modified UCB T cells to secrete IL-12p70, IFNγ and IL-2 in response to Nalm6 or Raji tumor cells was assessed using a luminex assay following coculture. 1928z/IL12 T cells secrete more IL-12p70 and IFNγ, and less IL-2 than 1928z T cells, *P < 0.05. (a) Proliferative capacity of modified UCB T cells was investigated by labeling T cells with membrane dye prior to coculture with Nalm6 tumor cells. Flow cytometry was utilized to detect dilution of membrane dye (proliferation of T cells). (b) 1928z/IL-12 T cells showed increased proliferation compared to 1928z T cells. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. (c) The ability of modified UCB T cells to lyse Raji or Nalm6 tumor cells was assessed using a 4-h 51Cr assay. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

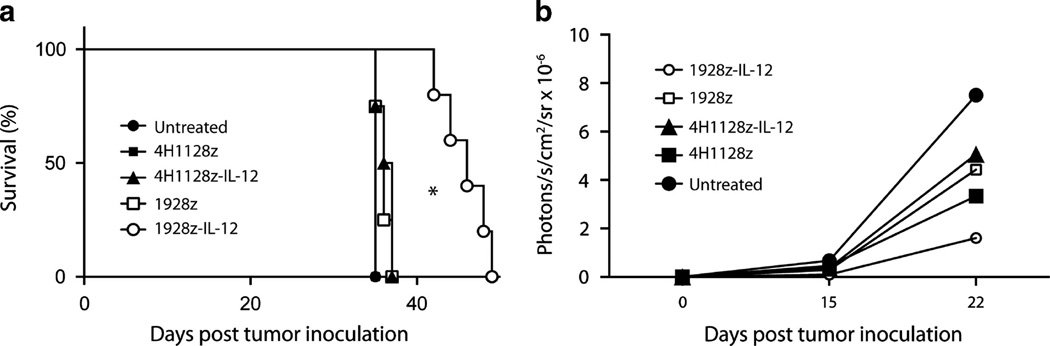

Finally, we investigated the in vivo antitumor capacity of transduced UCB-derived T cells using a preclinical SCID-Beige murine model. Initial experiments utilized Raji tumors and we showed that 1928z UCB T cells can cure mice without the need for irradiation or IL-2 support (Supplementary Figure 1). Therefore, to determine the effect of IL-12 transgene on the antitumor efficacy of these cells we used a more aggressive model employing Nalm6 tumor cells. Treatment of Nalm6 tumor-bearing mice with 5 × 106 CAR+ 1928z/IL-12 UCB-derived T cells resulted in significantly enhanced survival compared to mice treated with 1928z, 4H1128z or 4H1128zIL-12 or untreated mice (Figures 6a and b). Given that 1928z UCB T cells were cultured in exogenous IL-12 prior to adoptive transfer and these cells did not inhibit tumor progression, the requirement for continued autocrine IL-12 stimulation for the antitumor efficacy of 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells was demonstrated.

Figure 6.

1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells enhance the survival of tumor-bearing mice. (a) Mice inoculated with 1 × 106 Nalm6 tumor cells i.v. were treated with a systemic infusion of 5 × 106 CAR+ UCB T cells. Survival of Nalm6 tumor-bearing mice was significantly enhanced by treatment with 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells compared to CAR alone and control cells, *P < 0.05. (b) Bioluminescent imaging revealed decreased tumor growth in mice treated with 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells compared to 1928z, 4H1128z, 4H1128z/IL-12 UCB T cells or untreated mice. Data shown are from UCB T cells from two units.

DISCUSSION

Tumor-targeted CAR UCB T cells could greatly augment the antileukemic potency of UCBT. This has significant therapeutic implications for patients with high-risk or refractory disease. However, given the correlation between high cell dose and improved UCB transplant outcome, only a small percentage of the UCB unit would be available for T-cell isolation and generation of CAR UCB T cells. Therefore, maximal expansion of CAR UCB T cells is required for therapeutic application.18 Herein, we describe a novel protocol for expansion and genetic modification of UCB T cells that yields a clinically relevant dose of functional antitumor UCB T cells. Specifically, we demonstrate that ex vivo culture of UCB T cells with exogenous IL-12 and IL-15 resulted in optimal expansion, and that these cells have a unique central memory and effector phenotype for effective adoptive cell transfer therapy.

In this study, we first determined optimal cytokine cultures for maximal expansion of UCB T cells. Early UCB T-cell expansion studies utilized OKT3 and IL-2 resulting in a 39-fold expansion.19 An improved expansion of > 140-fold has since been demonstrated with CD3/CD28 magnetic beads. However, these expanded UCB T cells have an effector memory phenotype with loss of CCR7 expression.16 By contrast, our study revealed that culture in the context of exogenous IL-12 and IL-15 led to over 150-fold expansion of UCB T cells with expression of central memory markers and cytotoxic molecules. A 14-fold expansion of UCB T cells has been reported with IL-2, IL-7, IL-12 and IL-15 and autologous virus pulsed dendritic cells.20–22 By contrast, the 150-fold expansion achieved in our study will permit generation of clinically relevant T-cell doses. For example, in a recent 128-patient double unit UCBT Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center series (median weight 68 kilograms, kg), the median infused viable CD3+ cell dose of the dominant unit was 4.27 (0.8–15.3) × 106/kg.23 One-hundred fifty-fold expansion of even 5% of many UCB units could therefore provide T-cell doses in excess of what is routinely used in donor lymphocyte infusions in adult patients. These data combined with previously published clinical data using CAR T-cell therapy, we conclude that these numbers are sufficient for effective clinical use.9,10 Use of 10% of the graft to generate CAR T cells may be clinically feasible in smaller pediatric patients, and pursuing this approach in the context of single unit transplant in children is supported by the results of the recent pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) 0501 randomized trial of single- versus double-unit UCBT. Moreover, new data concerning the ability to optimize unit selection by considering the pre-freeze CD34+ cell dose could facilitate the safety of reserving a small percentage of the graft for adult patients.23

Although UCB T cells are a classically naive population, we demonstrated that following activation/transduction, CAR UCB T cells have high lytic capacity and can mount cytokine responses to tumor cells in vitro. Despite demonstrating the importance of IL-15 for UCB T-cell expansion, previous studies have shown that modifying T cells with an IL-15 transgene carries high risk of malignant transformation.24,25 Our results suggest that while IL-15 is important in UCB expansion, IL-12 is important for phenotypic changes, including increased CD62L, CD28, GzmB and IFNγ (Figures 2 and 3). In addition, previous studies from our laboratory show that CAR/IL-12 T cells mediate improved antitumor efficacy and may be resistant to Tregs. Therefore, we chose to use an IL-12 transgene in our retroviral CAR construct. Our expansion protocol and expression of 1928z/IL-12 resulted in a maintained central memory phenotype, in contrast to other studies where UCB T cells expressing a CD19-targeted CAR (with either 4-1BB or CD28 signaling domains) resulted in low levels of CD62L expression.26 Therefore, our studies support the use of IL-15 and IL-12 for UCB T-cell expansion and modification of UCB T cells with both the CAR and IL-12 for adoptive therapy.

The in vitro antitumor efficacy of these cells was measured by determining the cytokine release, T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity of CAR UCB T cells. 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells secreted significantly more IL-12 and, consequently, IFNγ, as well as decreased levels of IL-2. We have previously noted that reduced levels of IL-2 secretion from CAR/IL-12 T cells may relate to the mechanism for potential resistance to Tregs.17 UCB T cells mediate increased lysis of tumor targets when modified to express both CAR and IL-12.

Previous studies investigating the antitumor efficacy of modified UCB T cells failed to show long-term survival of tumor-bearing mice in a clinically relevant model.19,26 To investigate the in vivo antitumor efficacy of CAR UCB T cells, we initially employed Raji tumor cells inoculated into SCID-Beige mice. Our experiments revealed that 1928z UCB T cells were able to eliminate Raji tumor cells, resulting in 100% long-term survival of treated mice without the requirement for irradiation or exogenous IL-2 support (Supplementary Figure 1). To determine potentially improved antitumor efficacy mediated by 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells, we next utilized a more aggressive tumor model using Nalm6 tumor cells. We show that 1928z/IL-12 UCB T cells mediated enhanced antitumor efficacy against Nalm6 tumor in SCID-Beige mice as determined by both bioluminescent imaging and long-term survival studies. In this study, we demonstrated enhanced survival in 1928z/IL-12 UCB T-cell-treated mice without a need for pretreatment (irradiation) or IL-2 support. Effective therapy without the need for IL-2 and/or irradiation may promote the safety of adoptive cell transfer therapy when translated to the clinic.27

The safety of this approach will require further investigation due to the potential risks of transformation of modified T cells or exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease. Several other groups have demonstrated polyclonal expansion of UCB T cells suggesting that transformation has not previously occurred.16,28 However, it be will necessary to perform T-cell receptor-β gene immunosequencing to confirm that 1928z/IL-12 modified cells retain normal polyclonality of their TCR repertoire. Furthermore, despite a recent study showing CAR T-cell transfer following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation does not increase graft-versus-host disease, it may be necessary to incorporate a suicide gene into the UCB T cells.13 Inducible caspase9 is an attractive option as it has been demonstrated to rapidly eradicate transferred cells.29 Inclusion of the inducible caspase9 gene into the 1928z/IL-12 retroviral construct could allow eradication of modified cells in the case of serious adverse events, thereby improving the safety of this approach. Eradication of CAR T cells with the suicide gene will of course eliminate antitumor efficacy, which may result in decreased response to tumor or potential relapse.

Our findings provide strong rationale for the clinical translation of expanded CAR UCB T cells as additional therapy for UCBT recipients in a phase I study. We propose that adoptive transfer of CAR UCB T cells will augment graft-versus-leukemia effect, and thereby promote disease-free survival after UCBT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RJB is a co-founder, stockholder, and consultant for Juno Therapeutics.

HJP was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HJP designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. TJP and DGvL designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. KJC, JNB and RJB designed the experiments, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. SAG designed the experiments, analyzed the data.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Leukemia website (http://www.nature.com/leu)

REFERENCES

- 1.Eapen M, Rocha V, Sanz G, Scaradavou A, Zhang MJ, Arcese W, et al. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adults with acute leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:653–660. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponce DM, Zheng J, Gonzales AM, Lubin M, Heller G, Castro-Malaspina H, et al. Reduced late mortality risk contributes to similar survival after double-unit cord blood transplantation compared with related and unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1316–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker JN, Scaradavou A, Stevens CE. Combined effect of total nucleated cell dose and HLA match on transplantation outcome in 1061 cord blood recipients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2010;115:1843–1849. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunstein CG, Gutman JA, Weisdorf DJ, Woolfrey AE, Defor TE, Gooley TA, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: relative risks and benefits of double umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2010;116:4693–4699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verneris MR, Brunstein CG, Barker J, MacMillan ML, DeFor T, McKenna DH, et al. Relapse risk after umbilical cord blood transplantation: enhanced graft-versus-leukemia effect in recipients of 2 units. Blood. 2009;114:4293–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks DI, Woo KA, Zhong X, Appelbaum FR, Bachanova V, Barker JN, et al. Unrelated umbilical cord blood transplant for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete remission: a comparison with allografts from adult unrelated donors. Haematologica. 2014;99:322–328. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.094193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brentjens RJ, Santos E, Nikhamin Y, Yeh R, Matsushita M, La Perle K, et al. Genetically targeted T cells eradicate systemic acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5426–5435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang LX, Westwood JA, Moeller M, Duong CP, Wei WZ, Malaterre J, et al. Tumor ablation by gene-modified T cells in the absence of autoimmunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9591–9598. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH, Davila ML, Wang X, Stefanski J, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2011;118:4817–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, Park J, Wang X, Cowell LG, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:177ra38. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, Wilson WH, Spaner DE, Maric I, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood. 2012;119:2709–2720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Carpenter RO, Kassim SH, Rose JJ, Telford WG, et al. Donor-derived CD19-targeted T cells cause regression of malignancy persisting after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;122:4129–4139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brentjens RJ, Latouche JB, Santos E, Marti F, Gong MC, Lyddane C, et al. Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes co-stimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat Med. 2003;9:279–286. doi: 10.1038/nm827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong MC, Latouche JB, Krause A, Heston WD, Bander NH, Sadelain M. Cancer patient T cells genetically targeted to prostate-specific membrane antigen specifically lyse prostate cancer cells and release cytokines in response to prostate-specific membrane antigen. Neoplasia. 1999;1:123–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okas M, Gertow J, Uzunel M, Karlsson H, Westgren M, Karre K, et al. Clinical expansion of cord blood-derived T cells for use as donor lymphocyte infusion after cord blood transplantation. J Immunother. 2010;33:96–105. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b291a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pegram HJ, Lee JC, Hayman EG, Imperato GH, Tedder TF, Sadelain M, et al. Tumor-targeted T cells modified to secrete IL-12 eradicate systemic tumors without need for prior conditioning. Blood. 2012;119:4133–4141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, Baker KS, Blazar BR, Eide C, et al. Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102 patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and survival. Blood. 2002;100:1611–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrano LM, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, Numbenjapon T, Bennitt J, Kim D, et al. Differentiation of naive cord-blood T cells into CD19-specific cytolytic effectors for posttransplantation adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2006;107:2643–2652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Micklethwaite KP, Savoldo B, Hanley PJ, Leen AM, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Cooper LJ, et al. Derivation of human T lymphocytes from cord blood and peripheral blood with antiviral and antileukemic specificity from a single culture as protection against infection and relapse after stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:2695–2703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson KL, Ayello J, Hughes R, van de Ven C, Issitt L, Kurtzberg J, et al. Ex vivo expansion, maturation, and activation of umbilical cord blood-derived T lymphocytes with IL-2, IL-12, anti-CD3, and IL-7. Potential for adoptive cellular immunotherapy post-umbilical cord blood transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanley PJ, Cruz CR, Savoldo B, Leen AM, Stanojevic M, Khalil M, et al. Functionally active virus-specific T cells that target CMV, adenovirus, and EBV can be expanded from naive T-cell populations in cord blood and will target a range of viral epitopes. Blood. 2009;114:1958–1967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith KM, Tonon J, Evans KL, Lubin MN, Byam C, Ponce DM, et al. Analysis of 402 cord blood units to assess factors influencing infused viable CD34+ cell dose: the critical determinant of engraftment. Blood. 2013;122:296. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu C, Jones SA, Cohen CJ, Zheng Z, Kerstann K, Zhou J, et al. Cytokine-independent growth and clonal expansion of a primary human CD8+ T-cell clone following retroviral transduction with the IL-15 gene. Blood. 2007;109:5168–5177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fehniger TA, Suzuki K, Ponnappan A, VanDeusen JB, Cooper MA, Florea SM, et al. Fatal leukemia in interleukin 15 transgenic mice follows early expansions in natural killer and memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:219–231. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tammana S, Huang X, Wong M, Milone MC, Ma L, Levine BL, et al. 4-1BB and CD28 signaling plays a synergistic role in redirecting umbilical cord blood T cells against B-cell malignancies. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:75–86. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antony GK, Dudek AZ. Interleukin 2 in cancer therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:3297–3302. doi: 10.2174/092986710793176410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis CC, Marti LC, Sempowski GD, Jeyaraj DA, Szabolcs P. Interleukin-7 permits Th1/Tc1 maturation and promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood T cells: a critical step toward adoptive immunotherapy after cord blood transplantation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5249–5258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Stasi A, Tey SK, Dotti G, Fujita Y, Kennedy-Nasser A, Martinez C, et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1673–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.