Abstract

In recent years, there has been an increased use of neuroleptic agents in the primary care setting. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare complication of neuroleptic therapy that can be missed if not suspected. This manuscript reviews the diagnosis and management of NMS in the primary care setting. There is a lack of prospective data, and most of the information is obtained from case series. Physicians need to have a high index of suspicion with regard to excluding NMS in patients taking neuroleptics and presenting with hyperthermia.

The use of antipsychotic (neuroleptic) agents in the primary care setting is increasing for a variety of reasons, such as lack of access to psychiatric care; the advent of the atypical antipsychotics, which have a lower propensity for causing side effects; the increased use of the atypical antipsychotics to treat mood disorders; increased off-label use of atypical antipsychotics for anxiety disorders; and increased promotion by the pharmaceutical companies of the atypical agents in primary care and skilled nursing facilities.

Despite the fact that the atypical antipsychotics are safer and easier to use, side effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) are still reported. Little is known about NMS in general (most data are from case studies rather than research), and still less is known about the nature of presentation of NMS with the atypical agents. Hence, we need to be vigilant and have a high index of suspicion when patients are taking neuroleptics. This article will provide an overview of diagnosis and management of NMS.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Delay et al.1 were the first to describe neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) in 1960. The incidence of NMS with conventional antipsychotics has been shown to be anywhere from 0.02% to 2.44%.2,3 Prospective studies in 2 psychiatric hospitals in the Boston area found an incidence of 0.07% to 0.9%.4,5 NMS has been reported among patients of all ages; however, most cases have occurred between the ages of 20 and 50 years, possibly due to high antipsychotic usage.3

CAUSES

Although NMS is most commonly associated with antipsychotic usage, withdrawal of dopaminergic therapy such as levodopa and amantadine has also been reported to cause NMS. The syndrome has been reported with all antipsychotics, including atypicals such as clozapine,6–8 risperidone,9–13 quetiapine,2 and olanzapine.2 The use of metoclopramide and droperidol has also been implicated in the causation of NMS.14 Schizophrenia or affective disorders are the common diagnoses associated with NMS; however, NMS has also been reported with other conditions such as dementia, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, and Wilson's disease in patients exposed to antipsychotics or dopamine-depleting agents or those who have had abrupt discontinuation of dopamine agonists.3,15

DIAGNOSIS

One of the key interventions for decreasing the lethality in NMS is early detection. To make any early diagnosis, a high index of suspicion is required. Several diagnostic schemas have been proposed; however, there is no single set of criteria that is universally accepted. The reasons for these differences in diagnostic schemas are partly the lack of adequate prospective data on this illness and partly the fact that most of the information has been obtained from case studies. Nevertheless, there is agreement that elevated temperature (greater than or equal to 40°C, or 104°F); extrapyramidal symptoms, particularly lead-pipe rigidity; and autonomic instability (elevated or labile blood pressure, tachycardia, profuse diaphoresis, incontinence, and pallor) are considered cardinal features of NMS. Other findings that may help support the diagnosis are altered consciousness, tremor, mutism, leukocytosis, and elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels. It is important that other general medical conditions, as well as psychiatric disorders such as catatonia, are excluded prior to making the diagnosis of NMS.

The research criteria for NMS as listed in the DSM-IV16 require the presence of severe muscle rigidity and elevated temperature associated with neuroleptic medication use (Criterion A).16 In addition, the patient should have at least 2 other supportive symptoms such as diaphoresis, dysphagia, tremor, incontinence, changes in level of consciousness ranging from confusion to coma, mutism, tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, leukocytosis, or elevated CPK levels (Criterion B).16 General medical conditions and psychiatric disorders leading to NMS-like presentations should be excluded prior to making a diagnosis of NMS (Criteria C and D).16

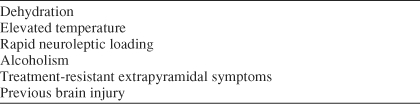

In a study17 delineating symptoms of NMS, the syndrome was characterized by hyperpyrexia, muscular rigidity, alterations in the level of consciousness, autonomic dysfunction, and elevated CPK levels and white blood cell count. The alteration in consciousness runs the gamut from confusion to coma. The risk factors for NMS noted in the literature include dehydration, elevated temperature, rapid neuroleptic loading, alcoholism, previous brain injury, and treatment-resistant extrapyramidal symptoms3,18 (Table 1). NMS may manifest with varying severity.

Table 1.

Risk Factors for Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

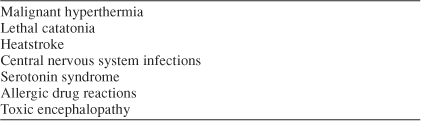

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of NMS (Table 2) includes malignant hyperthermia, which presents as clinically identical to NMS. It occurs following the administration of halogenated anesthetic agents and succinylcholine. The diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia can be made by exposing the biopsied muscle to halothane or caffeine, which results in a hypercontractile response not seen in NMS patients.3

Lethal catatonia begins with severe psychotic excitement, while NMS begins with rigidity. These 2 syndromes may be very difficult to distinguish.3,19 Neuroleptics should be stopped in both cases.3,20

Heatstroke should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Central nervous system infective processes, which include meningitis, encephalitis, and neurosyphilis, should also be considered as likely causes.

Serotonin syndrome is an uncommon toxic, hyper-serotonergic state that needs a high index of suspicion so as to make the diagnosis. Serotonin syndrome is characterized by mental status changes, tachycardia, diaphoresis, labile blood pressure changes, shivering, tachypnea, mydriasis, and sialorrhea. Hyperthermia has been observed in 34% of NMS cases.21 Neurologic manifestations include tremor, myoclonus, tachycardia, hyperreflexia, ankle clonus, muscle rigidity, and incoordination. Leukocytosis, rhabdomyolysis, and elevated CPK levels are common.21

Allergic drug reactions may resemble NMS, as they also produce fever and autonomic instability.

Toxic encephalopathies such as tetanus, botulism, and anticholinergic delirium should also be considered when making the final diagnosis.3 The cerebral spinal fluid in NMS does not demonstrate the changes seen in central nervous system infections.

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

COMPLICATIONS

Estimates of mortality in NMS cases have ranged as high as 76%, although most reports put it between 10% and 20%,36 due primarily to complications such as cardiovascular collapse, arrhythmia, renal failure, and respiratory failure. At least 3 NMS-attributed deaths have been reported with the use of atypical antipsychotics—1 with olanzapine and 2 with risperidone.2 Rhabdomyolysis is the most serious complication associated with NMS. Dementia, parkinsonism, dyskinesias, and ataxia are some of the permanent neurologic complications that may occur in survivors.3,22

MANAGEMENT

Pelonero and colleagues3 suggest 6 initial important steps to be taken: (1) stop neuroleptic therapy, (2) seek appropriate consultation, (3) transfer the patient promptly to the best care setting, (4) document a differential diagnosis plan, (5) document a treatment plan, and (6) inform the family.

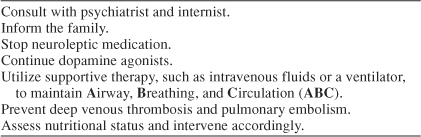

General Measures

The management of a suspected or diagnosed case of NMS depends on the severity of symptoms. It would be prudent at the time of suspicion to involve the expertise of a psychiatrist for further clarification of the diagnosis and an internist for management of the patient. The family must be informed of and kept updated about the patient's condition. Mild cases may be treated on a psychiatric in-patient basis, whereas the more severe cases are treated in the medical intensive care unit. The following steps need to be undertaken with close collaboration with a psychiatrist and an internist (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nonpharmacologic Measures in Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Specific Steps

The first and most critical step in the treatment of NMS is discontinuation of the neuroleptic medication.3

If dopamine agonists such as amantadine are being used, they should be continued, as their sudden withdrawal may worsen symptomatology.3

Supportive therapies, which include intravenous fluids to correct dehydration, use of antipyretics, and electric blanket for gradual reduction in temperature, are important measures to be considered. Some patients may require ventilator support if their respiratory system is involved in the rigidity. It is important to assess the gag reflex; if the reflex is lost, parenteral nutrition may be needed.3

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are prevented by the use of subcutaneous heparin.

If renal failure occurs, dialysis may be considered.

The nutritional status of the patient needs to be assessed on an ongoing basis. As the patient is under considerable stress during an episode of NMS, comorbid illnesses such as diabetes may lead to ketoacidosis and need to be monitored closely.3

Pharmacologic and Other Interventions

Supportive therapy is instituted first, and pharmacologic treatment may then be considered if the patient does not improve.

When? If the condition of the patient is declining (e.g., increasing rigidity, persistent hyperpyrexia, increasing symptoms), medication treatment should be started (Table 4).23,24

Table 4.

Pharmacologic Intervention for Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

What? Bromocriptine is usually the drug of choice, started at a dosage of 2.5 mg 2 or 3 times daily and titrated to a maximum dosage of 45 mg per day.24 Side effects to be assessed include nausea, vomiting, psychosis, and altered mental status.

Dantrolene is used in cases of severe hyperthermia. Its efficacy has been demonstrated in malignant hyperthermia. This drug is administered by bolus injection in a dosage of 1 to 10 mg/kg (oral dosage 50–600 mg) of body weight.24

The 2 agents bromocriptine and dantrolene may be used in combination depending on the severity of the clinical situation. Rosebush and Stewart25 found that dantrolene and bromocriptine did not improve time to response compared with supportive measures, while another report was to the contrary.26 In a large case analysis,27 medications such as bromocriptine, dantrolene, and amantadine were found to be the most effective agents for treating NMS.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has also been found to be effective for the treatment of NMS and the underlying psychiatric condition.28–30 Iron supplementation has been suggested for those individuals with iron deficiency, as low iron levels may aggravate movement disorders.31

Course

NMS may run a clinical course anywhere from 2 to 14 days. In patients on depot neuroleptics, the resolution of symptoms may take up to 35 days from the last injection.

Posttreatment Plan

After the resolution of NMS, it is essential to continue treatment of the patient with the help of a psychiatrist. Therapeutic alternatives to neuroleptics, such as lithium, benzodiazepine, anticonvulsants, and ECT, should be considered after recovery from NMS.3 In some patients, due to the persistent nature of the symptoms, neuroleptics may be essential. In such patients, neuroleptics from a class other than the one causing NMS should be used.3 Atypical antipsychotics have lower affinity for the nigrostriatal D2 receptors and hence could be considered for patients needing retreatment.3

It should be noted that NMS has also been reported with atypical neuroleptics.2 High-potency neuroleptics have been reported to be a possible risk factor for recurrence of NMS. Rosebush and colleagues32 have recommended a 2-week interval between recovery and the reintroduction of neuroleptics. Despite the seriousness of the condition, neuroleptics can often be reintroduced and used safely.33 Anesthesia can be given safely to patients post-NMS, unlike in the case of malignant hyperthermia. Patients with a history of NMS are not good candidates for long-acting (depot) preparations.3

CONCLUSION

Prospective studies of NMS are difficult to conduct because of the infrequent and serious nature of the disorder. NMS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient with high fever and marked rigidity. There remain controversies about treatment specifics among leaders in the field; however, there is agreement about measures such as rapid cooling to decrease temperature, maintaining hydration, and anticoagulation.3

A greater awareness of this disorder needs to be created among primary care physicians and internists, and the Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service (NMSIS) is aiming to fill this void by collecting data. NMS is a source of malpractice litigation, especially if there is a bad outcome.34,35 For physicians seeking information or consultation about a clinical case of NMS, the NMSIS can serve as a reliable resource. The case can be discussed with one of the consultants staffing the service's hotline, which is staffed 24 hours a day year-round. The number to call is 1-888-NMS-TEMP; e-mail: info@nmsis.org; Web site: www.nmsis.org.

Drug names: amantadine (Symmetrel and others), bromocriptine (Parlodel and others), clozapine (Clozaril, Fazaclo, and others), dantrolene (Dantrium), droperidol (Inapsine and others), heparin (Hepflush-10, Heparin Lock Flush, and others), lithium (Lithobid, Eskalith, and others), metoclopramide (Reglan and others), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal).

Footnotes

The authors report no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Delay J, Pichot P, and Lemperiere T. et al. Un neuroleptique majeur non phenothiazine et non reserpine, l'haloperidol, dans le traitement des psychoses [A non-phenothiazine and non-reserpine major neuroleptic, haloperidol, in the treatment of psychoses.]. Ann Med Psychol (Paris). 1960 118:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth J, Parameswaran S, and Gunatilake S. et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and atypical antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 65:464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelonero AL, Levenson JL, Pandurangi AK.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1163–1172. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.9.1163.1075-2730(1998)049<1163:NMSAR>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ, Bellinghausen B, and Wojick JD. et al. A prospective survey of neuroleptic malignant syndrome in a short-term psychiatric hospital. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 145:517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE Jr, Sebastianelli J, and Pope HG Jr. et al. Frequency and presentation of neuroleptic malignant syndrome in a state psychiatric hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989 50:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG Jr, Cole JO, and Choras PT. et al. Apparent neuroleptic malignant syndrome with clozapine and lithium. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986 174:493–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller T, Becker T, Fritze J.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome after clozapine plus carbamezapine [letter] Lancet. 1988;2:1500. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90986-5.0140-6736(1988)002<1500:NMSACP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P, Kruk J, and Kneebone M. et al. Clozapine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome: review and report of new cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995 15:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitasuo V.. Risperidone-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome in a young patient [letter] Lancet. 1994;344:1705. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90489-8.0140-6736(1994)344<1705:RNMSIA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Ryan J, and Mullett G. et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with the use of risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic agent. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1994 9:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- Webster P, Wijeratne C.. Risperidone-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome [letter] Lancet. 1994;344:1228–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90542-8.0140-6736(1994)344<1228:RNMSL>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave M.. Two cases of risperidone-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome [letter] Am J Psychiatry. 1994;152:1233–1234. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1233b.0002-953X(1994)152<1233:TCORNM>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsy D.. Risperidone and neuroleptic malignant syndrome [letter] JAMA. 1996;275:446.0098-7484(1996)275<0446:RANMSL>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LS, Weinrauch LA, D'Elia JA.. Metoclopromide induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1495–1497.0003-9926(1987)147<1495:MINMS>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JH, Feinberg SS, Feldman RG.. A neuroleptic malignantlike syndrome due to levodopa therapy withdrawal. JAMA. 1985;254:2792–2795.0098-7484(1985)254<2792:ANMSDT>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Addonizio G, Susman VL, Roth SD.. Symptoms of neuroleptic malignant syndrome in 82 consecutive inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1587–1590. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.12.1587.0002-953X(1986)143<1587:SONMSI>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velamor VR.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Drug Saf. 1998;19:73–82. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199819010-00006.0114-5916(1998)019<0073:NMS>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo E, Rubin RT, Holsboer-Trachsler E.. Clinical differentiation between lethal catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:324–328. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.3.324.0002-953X(1989)146<0324:CDBLCA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann SC, Caroff SN, and Bleier HR. et al. Lethal catatonia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986 143:1374–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE Jr, Arnold LM.. The serotonin syndrome. Psychiatr Ann. 2000;30:333–343.0048-5713(2000)030<0333:TSS>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SB, Alvarez WA, Freinhar JP.. Rhabdomyolysis in retrospect; are psychiatric patients predisposed to this little known syndrome? Int J Psychiatry Med. 1987;17:163–171. doi: 10.2190/pw4m-bq2x-0ft2-j6ml.0091-2174(1987)017<0163:RIAPPP>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addonizio G, Susman VL, Roth SD.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: review and analysis of 115 cases. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:1004–1020. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(87)90010-2.0006-3223(1987)022<1004:NMSRAA>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus A, Mann SC, and Caroff SN. The Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome and Related Conditions. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Rosebush P, Stewart T.. A prospective analysis of 24 episodes of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:717–725. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.6.717.0002-953X(1989)146<0717:APAOEO>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas P, Davis JM, and Hua J. et al. Pharmacotherapy of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatr Ann. 1991 21:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MR, Green M.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: review of response to therapy [review] Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1927–1931. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.9.1927.0003-9926(1989)149<1927:NMSROR>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addonizio G, Susman VL.. ECT as a treatment alternative for patients with symptoms of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:102–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheftner WA, Shulman RB.. Treatment of choice in neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Convuls Ther. 1992;8:267–279.0749-8055(1992)008<0267:TOCINM>2.0.CO;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Janicak PG, and Sakkas P. et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Convuls Ther. 1991 7:111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Lenox RH.. Is there a rationale for iron supplementation in the treatment of akathisia? a review of the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:476–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosebush PI, Stewart T, Gelenberg AJ.. Twenty neuroleptic rechallenges after neuroleptic malignant syndrome in 15 patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:295–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG Jr, Aizley HG, and Keck PE Jr. et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: long-term follow-up of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991 52:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair TD, Dauner A.. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: liability in nursing practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1993;31:5–12. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19930201-06.0279-3695(1993)031<0005:NMSLIN>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannas PA, Packar JV.. A fatal case of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Med Sci Law. 1993;33:86–88. doi: 10.1177/002580249303300118.0025-8024(1993)033<0086:AFCONM>2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Hermesh H, Munitz H.. Mortality from neuroleptic malignant syndrome [review] J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]