Abstract

People who use drugs (PWUD) represent a key high risk group for tuberculosis (TB). The prevalence of both latent TB infection (LTBI) and active disease in drug treatment centers in Malaysia is unknown. A cross-sectional convenience survey was conducted to assess the prevalence and correlates of LTBI among attendees at a recently created voluntary drug treatment center using a standardized questionnaire and tuberculin skin testing (TST). Participants (N = 196) were mostly men (95%), under 40 (median age = 36 years) and reported heroin use immediately before treatment entry (75%). Positive TST prevalence was 86.7%. Nine (4.6%) participants were HIV-infected. Previous arrest/incarcerations (AOR = 1.1 for every entry, p < 0.05) and not being HIV-infected (AOR = 6.04, p = 0.03) were significantly associated with TST positivity. There is an urgent need to establish TB screening and treatment programs in substance abuse treatment centers and to tailor service delivery to the complex treatment needs of patients with multiple medical and psychiatric co-morbidities.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Substance use, HIV, Integration, Malaysia

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with a global burden of 8.8 million incident cases and 1.4 million TB-attributed deaths in 2010. Almost 80% of these cases were from the African and Asian regions and 13% of incident cases occurred among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011a). Despite declining incidence since 2002, many countries in these two regions are unlikely to achieve the TB-related United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDG) by 2015 (Ooms, Stuckler, Basu, & McKee, 2010; World Health Organization (WHO), 2011a).

Among other marginalized populations, people who use drugs (PWUD) represent a group recognized to be at high risk for TB infection and disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2005; Nava-Aguilera et al., 2009). This is believed to be related to the drug use environment (close proximity at drug use site), prior experiences of incarceration in closed spaces with high-risk individuals, frequent homelessness, poor nutritional status, co-morbid alcohol use disorders, poor access to health services and highly prevalent HIV infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2005; Deiss, Rodwell, & Garfein, 2009). A systematic review of TB transmission studies showed that PWUD were 3-times more likely to be recently infected with TB than non-drug users (Nava-Aguilera et al., 2009). Furthermore, the worldwide prevalence of latent TB infection (LTBI) in PWUDs (reported to be around 10–59% from various settings) is higher than that of the general population (Deiss et al., 2009). In many countries, incidence of active TB disease (estimated at 1–2 per 100 person–year) (Hwang, Grimes, Beasley, & Graviss, 2009) and TB-related mortality, particularly among PLWHA, are markedly higher than overall national rates (Deiss et al., 2009; World Health Organization (WHO), 2008).

Malaysia is a middle-income country with an estimated intermediate TB incidence and mortality of 82 and 8.5 cases per 100,000 population, respectively, with 9% of TB cases being diagnosed among PLWHA (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011a). HIV prevalence (0.4%) nationwide, however, is concentrated among people who inject drugs (PWID), who represent nearly three quarters of PLWHA in Malaysia (Choi et al., 2010). Prior to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Malaysia, the government responded to growing rates of illicit drug use by forming an anti-drug task force, criminalizing drug possession and instituting compulsory rehabilitation of PWUD, entailing a compulsory period of detention of 2 years. In 2007, over 54,000 individuals were detained in 28 compulsory drug detention centers (CDDCs) throughout the country under the Dangerous Drug Act (1952). Apart from mandatory HIV testing upon arrival, no further systematic medical screening or care is provided and abstinence from drug use is enforced as a form of ‘treatment’ (Fu, Bazazi, Altice, Mohamed, & Kamarulzaman, 2012; World Health Organization (WHO), 2009). With high relapse rates (70–90%) post-release from CDDCs along with the recognition that these measures are neither clinically effective nor cost-effective and that national HIV control lags behind the MDG, the Malaysian government began to shift its response, starting with establishing the National Strategic Plan on HIV/AIDS in 2006 (Csete et al., 2011; World Health Organization (WHO), 2009). The national HIV/AIDS strategy initiated the development of an HIV/AIDS surveillance system, established voluntary HIV testing and counseling programs and needle and syringe exchange programs (NSEP), and improved access to methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Reid, Kamarulzaman, & Sran, 2007). After decades of deploying only punitive approaches to address illicit drug use, the National Anti-Drug Agency (NADA) recently adopted an innovative voluntary model to treat PWUD, which aligns with recent UNAIDS recommendations (World Health Organization (WHO), 2009, 2011b). These newly developed “Cure and Care” (C&C) centers provide free, voluntary access to MMT for opioid-dependent individuals as well as voluntary inpatient treatment for up to 90 days.

Although data suggests a high prevalence of TB in closed settings and among individuals enrolled in substance abuse treatment programs, there is a lack of available data from Malaysia. To address this gap in knowledge, a survey was conducted to assess the prevalence of LTBI among attendees of a C&C center in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2. Materials and methods

From December 2011 to February 2012, a cross-sectional standardized TB survey was conducted among attendees of the C&C Clinic in Sungai Besi, Kuala Lumpur. Managed by NADA, the facility is one of the eight CDDCs that have recently been converted into voluntary substance abuse treatment centers. With the ability to accommodate up to 200 individuals, the facility offers inpatient care, counseling and methadone therapy (MMT) for a maximum period of 3 months. All C&C clinic services are free of charge. Participants on MMT receive treatment for up to 90 days, and can continue receiving methadone at this clinic or can be referred to another community-based MMT program closer to their homes, operated either by NADA or the Ministry of Health. Unlike CDDCs, where HIV testing is compulsory, voluntary testing is provided but no further HIV or other medical (including TB) services are available onsite. PLWHA and those with other medical or psychiatric co-morbidities are referred to community hospitals for further management.

Inpatient clients and attendees of the outpatient MMT program were approached for study participation, involving a brief health survey and TB screening. After those who agreed to participate underwent informed consent, participants were interviewed face-to-face using a structured questionnaire. Study questionnaires were translated and back translated from English into Bahasa Malaysia and administered by trained research assistants. Questionnaire content included socio-demographic, drug use, drug treatment, previous arrests and incarcerations, and diagnosis and treatment of HIV, TB and other diseases. Prior Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination was verified by the examination of a scar on the left deltoid region. Participants were screened clinically for TB using the WHO symptom scoring: cough >2 weeks (2 points), expectoration (2 points), weight loss (1 point), loss of appetite (1 point) and chest pain (1 point) (World Health Organization (WHO), 2000). Subjects suspected of having active TB (5 points or more) were referred to a community hospital for further assessment. A tuberculin skin test (TST) was placed intradermally using 0.1 mL (2 TU) of RT-23 SSI (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark) and read after 48–72 hours for those who were initially symptom-free or whom active TB was excluded. TST reactivity was defined as induration size of ≥10 mm among HIV-uninfected or those with unknown HIV status, and ≥5 mm among HIV-infected participants (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2000). Two-step TST testing was performed 1 week later for initially TST-negative participants and anergy testing was not provided. Individuals with positive TST were referred to a community hospital to be counseled and assessed for eligibility for starting isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT).

Categorical variables were presented using frequencies, while continuous variables were presented with the median and either standard deviation (SD) or interquartile range (IQR) depending on the variable’s distribution normality. The primary study outcome was TST reactivity, and covariates associated with TST positivity significant at the p < 0.1 level in bivariate regression models were included in the multivariate regression analysis. In multivariate models, associations were considered significant at the p < 0.05 level. Income was categorized according to the Malaysian poverty line income of 800 Malaysian ringgit (MYR) (The Economic Planning Unit Prime Minister’s Department, 2010) and BCG vaccination was categorized as having been vaccinated either once or twice over one’s lifetime (first at infancy and a booster at either 6 or 12 years old) (Rafiza, Rampal, & Tahir, 2011).

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of University of Malaya Medical Centre.

3. Results

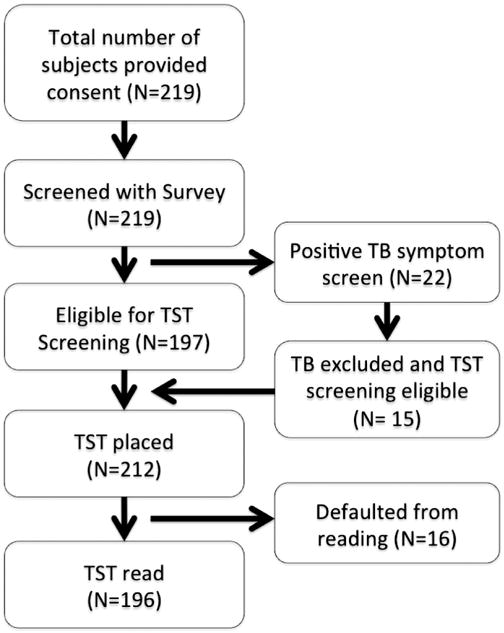

The disposition of participants is depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 219 C&C Clinic attendees agreed to participate in the study. Twenty two (10%) reported having symptoms associated with active TB based on the initial TB symptom screening (WHO TB symptom scores of 5 or more) and were referred to a community hospital for further assessment. Although none of these 22 individuals had active TB, only 15 agreed to subsequent TST, resulting in a total of 212 subjects who underwent final testing. Of this total, 16 (7.5%) defaulted from TST reading, resulting in 196 (89.5%) participants in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Participants’ disposition. Legend: TB: tuberculosis; TST: tuberculin skin test.

Overall, the reactive TST prevalence in this sample was 86.7%, with a median induration size of 15 mm (SD = 5.78; range 0–30 mm). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study sample and the correlates of being TST-positive. The majority of participants were men (95.9%), under the age of 40-year old (median age 36, SD = 9.28) and of Malay ethnicity (78.6%). Nearly all (93.9%) participants reported being previously incarcerated and having been in jails, prisons and/or CDDCs for a median of 7 times (IQR = 3–11) and for a median duration of incarceration of 114 weeks (IQR = 23.3–271.5). Only nine (4.6%) participants self-reported being HIV-infected, and most (89.3%) participants had been HIV-tested, primarily through mandatory HIV testing programs in prisons, jails and CDDCs.

Table 1.

Correlates of tuberculin skin test positivity.

| Variable | N (total = 196) | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | p value | Adjusted OR (95% confidence interval) | p value | ||

| Residence in Malaysia | |||||

| Other states | 40 | Referent | |||

| Klang Valley | 156 | 0.68 | 0.49 | ||

| Age | All | 1.03 | 0.14 | ||

| Institutional status | |||||

| Outpatient | 35 | Referent | |||

| Inpatient | 161 | 1.11 | 0.84 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 8 | Referent | |||

| Male | 188 | 2.28 | 0.33 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Others | 42 | Referent | |||

| Malay | 154 | 1.11 | 0.83 | ||

| Secondary school completed | |||||

| Yes | 90 | Referent | |||

| No | 106 | 0.58 | 0.22 | ||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 30 | Referent | |||

| Not married | 166 | 0.19 | 0.11 | ||

| Monthly income (MYR)a | |||||

| >800 | 112 | Referent | |||

| ≤800 | 84 | 0.72 | 0.43 | ||

| Duration of engagement in treatment | All | 0.99 | 0.83 | ||

| Stable job in the past 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 82 | Referent | |||

| No | 114 | 1.22 | 0.63 | ||

| Ever arrested and/or incarcerated | |||||

| No | 12 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 184 | 2.33 | 0.22 | ||

| Times of being arrested and/or incarcerated | All | 1.07 | 0.08 | 1.1 (1–1.2) | 0.05 |

| Duration of incarceration (weeks) | All | 1 | 0.11 | ||

| Drug use duration | All | 1.03 | 0.13 | ||

| Recent Drug use | |||||

| Heroin use | |||||

| No | 49 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 147 | 2.55 | 0.03 | 1.85 (0.71–4.85) | 0.21 |

| Methamphetamine use | |||||

| No | 128 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 68 | 1.00 | 0.99 | ||

| Polydrug use (both heroin and methamphetamine) | |||||

| No | 142 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 54 | 1.3 | 0.58 | ||

| Ever injected drugs | |||||

| No | 65 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 131 | 1.57 | 0.29 | ||

| On methadone therapy | |||||

| No | 52 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 144 | 2.31 | 0.055 | 2.16 (0.82–5.67) | 0.12 |

| HIV infection | |||||

| Yes | 9 | Referent | |||

| No | 166 | 3.45 | 0.096 | 6.04 (1.11–32.79) | 0.03 |

| BCGb 2 doses | |||||

| No | 48 | Referent | |||

| Yes | 148 | 1.78 | 0.20 | ||

MYR: Malaysian Ringgit.

BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin.

Essentially all (99%) participants were vaccinated with BCG and three quarters of the participants were vaccinated twice: the first at infancy and the second either at 6 or 12 years old during primary school, in accordance with the Malaysian Ministry of Health policy for TB prevention. This practice was abolished in Malaysia in 2005 and BCG vaccination is currently offered only to newborns (Rafiza et al., 2011). Ten (5%) participants believed that they previously had active TB but medical records were not available for verification.

Only four variables were significantly correlated with being TST positive in the bivariate analysis: number of times of previous entry into a correctional setting, not being HIV-infected, recent use of heroin and receipt of MMT. After adjusting for potential confounders, TST positivity was significantly associated with incarceration (AOR = 1.1 for every entry into a correctional setting, p < 0.05) and not being HIV-infected (AOR = 6.04, p = 0.03).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first structured TB survey conducted among attendees of a drug rehabilitation center in Malaysia. Of note is the higher prevalence (86.7%) of TST positivity in this sample compared to the reported reactive TST prevalence among PWUD elsewhere (ranging from 10 to 59% in various international settings) (Deiss et al., 2009) and provides direct empiric evidence for the role of previous incarceration and detention on facilitating TB infection.

Reports from other settings, though mostly conducted in low TB burden countries, confirm a high LTBI prevalence in this at-risk population (Deiss et al., 2009). TB survey reports from the United States revealed TST positivity prevalence of 14% from an NSEP center in New York (Salomon, Perlman, Friedmann, Ziluck, & Des Jarlais, 2000) and 15.7% in an MMT clinic in New Haven (Durante, Selwyn, & O’Connor, 1998). Increasing age and duration of injection drug use were the main correlates of TST positivity among attendees at these centers. Positive TST prevalence among clients of substance use treatment centers in Canada was higher than reported in the United States. Compared to the LTBI prevalence of 0.4–16.4% in the general population (Rusen, Yuan, & Millson, 1999), a LTBI survey among PWID in Montreal revealed a prevalence of 22% (Brassard, Bruneau, Schwartzman, Senecal, & Menzies, 2004), while a prevalence of 31% was reported among attendees of NSEP in Toronto (Rusen et al., 1999). The reason for higher LTBI prevalence in the Canadian studies might be related to the use of lower TST cut-off of 5 mm, regardless of the HIV status. Utilizing interferon gamma release assay (IGRA), a survey in Estonia reported a very low LTBI prevalence (7.4%) among MMT attendees (Ruutel et al., 2011), while a similar report from the United States showed higher prevalence (34%) of IGRA positivity among crack cocaine smokers in Texas (Grimes, Hwang, Williams, Austin, & Graviss, 2007).

The high prevalence of TST positivity in this sample compared to other studies might be related to several factors. Correctional settings are highly conducive to TB transmission (Restum, 2005) given poor ventilation, lack of routine TB screening, inadequate access to health services and the concentration of people with risk factors for progression to active TB disease (HIV infection, PWUD and low socio-economic background) (Al-Darraji, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2012). Taken together, these factors create the “perfect storm” for facilitating TB transmission and causing a high prevalence of TB (estimated to be 100 times higher compared to the general population) in these settings (World Health Organization (WHO), 2000). The majority (93.9%) of our participants had been admitted into a confined setting (jail, prison or drug detention center) at least once in their lifetime and participants with previous entry into these settings had an increased TST positivity risk of 1.1 for each additional entry into a confined setting. This high incarceration rate is largely the result of the intensive criminalization of drug use in Malaysia (World Health Organization (WHO), 2009). One recent survey among HIV-infected prisoners in the Kuala Lumpur region showed a similarly high (85%) prevalence of reactive TST (Al-Darraji, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2011) while another survey among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected prisoners in the northeastern state of Kelantan showed a TST-reactive prevalence of 87.6%, and similarly showed that prior incarceration was associated with TST positivity (Margolis, Al-Darraji, Wickersham, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2013). Taken together, the high TST prevalence in this community drug treatment setting likely represents the trans-institutationalization from prisons to communities of PWUDs, suggesting the need for expanded community-based drug treatment programs, potentially as an alternative to incarceration, coupled with the need to integrate TB screening and preventive measures into these settings.

Drug treatment programs, especially MMT programs where patients congregate for medications and counseling, may be settings in which TB, including multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) transmission, may occur given the congregation of high-risk individuals (Conover et al., 2001). An effective TB control program in Malaysian drug treatment centers would involve establishing routine TB screening and expanding provision of IPT alongside other previously described infection control measures (Friedland, 2010).

Although BCG vaccination may reduce TST specificity if performed after the first year of life (Farhat, Greenaway, Pai, & Menzies, 2006), repeated BCG vaccination did not significantly influence TST reactivity (Al-Darraji et al., 2011; Tan, Kamarulzaman, Liam, & Lee, 2002). This study confirms earlier reports that HIV infection, presumably through its negative influence on the immune system (Robles et al., 1999), is associated with lower rates of TST positivity among PWUD, even if the TST positivity cut-off was lowered to 5 mm (Graham et al., 1992). In this study, PWUDs without HIV infection were at 6-fold more likely to be TST positive (p = 0.03) than their HIV-infected counterparts after adjusting for other potential confounders. Although IPT is more effective among people with positive TST (Akolo, Adetifa, Shepperd, & Volmink, 2010), the WHO recommends IPT to all PLWHA regardless of the TST reaction because of the high risk of TB reactivation and reinfection among this particular population (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011c).

TB screening and treatment services may represent an important primary contact point for PLWHA and PWUDs, and co-location of services for multiple morbidities has the potential to improve access to and delivery of care for this at-risk population (Deiss et al., 2009; Sylla, Bruce, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2007; World Health Organization (WHO), 2008). TB screening and provision of directly observed preventive therapy (DOPT) using isoniazid has been shown to be effective and cost-saving when coupled with NSEP or MMT programs, irrespective of whether monetary incentives were added to improve adherence to follow up visits (Deiss et al., 2009; Perlman et al., 2001; Scholten et al., 2003; Snyder et al., 1999). Of note, the main reason for IPT non-completion among attendees of an MMT center in the United States was administrative discharge from the program (O’Connor et al., 1999). On the other hand, MMT or any other effective opioid substitution therapy (OST) program provided in voluntary settings is considered central to improving treatment outcomes for other diseases, including HIV (Altice et al., 2011; Berg, Litwin, Li, Heo, & Arnsten, 2011; Lucas et al., 2010) and HCV (Bruce et al., 2012; Litwin, Berg, Li, Hidalgo, & Arnsten, 2011) infections. The added contribution of TB services might ultimately contribute to reduced morbidity and mortality from these overlapping co-morbidities (Pollack, D’Aunno, & Lamar, 2006). In a report from New York, the co-location of HIV prevention and primary care services in drug treatment programs was found to be effective in delivering high-quality HIV services to PWUD. These programs provide a large population of PWID or PWUD with access to HIV care, utilizing the expertise of drug treatment staff in serving this population (Rothman et al., 2007). Despite the potential synergistic impact of addressing multiple co-morbidities, many countries challenged with the syndemic of HIV, TB and substance use frequently develop uncoordinated vertical programs, which are managed separately at the local and national levels (Ruutel et al., 2011; Sylla et al., 2007). Additionally, the provision of effective management and interventions of multiple co-morbidities for PWUD have been complicated by multi-level barriers to accessing health services and reciprocal mistrust between PWUD and conventional health care providers (Altice, Kamarulzaman, Soriano, Schechter & Friedland, 2010; Rothman et al., 2007).

To increase access to health services for marginalized populations confronting multiple, prevalent morbidities, the WHO has recommended a model of ‘one-stop shopping’ in which an array of services for PWUDs (e.g., HIV, TB, OST, NSEPs, etc) would be provided free to individuals needing care (Sylla et al., 2007; World Health Organization (WHO), 2008). Importantly, specific adherence support measures, implemented in collaboration with key community partners, are needed to improve low levels of adherence to treatment regimens and clinical follow-up visits (Binford, Kahana, & Altice, 2012; Meyer, Althoff, & Altice, 2013).

The study is limited by the nonavailability of a gold standard diagnostic test for LTBI. TST is neither 100% sensitive nor specific in diagnosing LTBI and is influenced by the immune status of the individual and previous BCG vaccination. The new IGRA assays perform better than TST but its high cost and technical complexity hamper its potential to be immediately expanded in low- to middle-income countries (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011d). There also does not exist a comparative estimate of the TST reactivity in the Malaysian general population, though the prevalence among Malaysian healthcare workers (52.1%) (Tan et al., 2002) and in the general population in the Western Pacific region (36%) (Dye, Scheele, Dolin, Pathania, & Raviglione, 1999) are markedly lower.

5. Conclusions

PWUDs remain at high risk of LTBI and progression to active disease. This marginalized population has poor access to health services due to criminalization, stigma and lack of community support. Drug treatment centers can provide an effective and cost-effective platform to deliver integrated medical and public health services to prevent and treat HIV, TB and substance use disorders in this socially marginalized population. There is an urgent need to expand integration of these healthcare services in countries where HIV, TB and substance use disorders are especially prevalent among PWUDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the director and the staff of the National Anti-Drug Agency (NADA) in Malaysia for their support in conducting the research in their facility. The funding for this research was provided by the University of Malaya HIR Grant (HIRGA E000001-20001) and the National Institutes on Drug Abuse for Research (R01 DA025943) and Career Development Award for FLA (K24 DA017072). Part of the study was orally presented at the 43rd Union World Conference on Lung Health, Kuala Lumpur, 13–17 November 2012.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;1:CD000171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Darraji HA, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. High Prevalence of TB/HIV Co-infection in a Malaysian Prison. Paper presented at the 42nd World Conference on Lung Health of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Poster Presentation (PC-944-28); Lille, France. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Darraji HA, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Isoniazid preventive therapy in correctional facilities: A systematic review. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2012;16:871–879. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: Results from a multisite study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S22–S32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. The Lancet. 2010;376:367–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Litwin A, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy improves adherence and viral load in drug users attending methadone maintenance clinics: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binford MC, Kahana SY, Altice FL. A systematic review of antiretroviral adherence interventions for HIV-infected people who use drugs. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2012;9:287–312. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard P, Bruneau J, Schwartzman K, Senecal M, Menzies D. Yield of tuberculin screening among injection drug users. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2004;8:988–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Eiserman J, Acosta A, Gote C, Lim JK, Altice FL. Developing a modified directly observed therapy intervention for hepatitis C treatment in a methadone maintenance program: Implications for program replication. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:206–212. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: CDC. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis; Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC. MMWR. 2005;54:1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P, Kavasery R, Desai MM, Govindasamy S, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Prevalence and correlates of community re-entry challenges faced by HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2010;21:416–423. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover C, Ridzon R, Valway S, Schoenstadt L, McAuley J, Onorato I, et al. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at a methadone treatment program. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2001;5:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csete J, Kaplan K, Hayashi K, Fairbairn N, Suwannawong P, Zhang R, et al. Compulsory drug detention center experiences among a community-based sample of injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2011;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiss RG, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS. Tuberculosis and illicit drug use: Review and update. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:72–82. doi: 10.1086/594126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante AJ, Selwyn PA, O’Connor PG. Risk factors for and knowledge of mycobacterium tuberculosis infection among drug users in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 1998;93:1393–1401. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.939139310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, Menzies D. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: What is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2006;10:1192–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland G. Infectious disease comorbidities adversely affecting substance users with HIV: Hepatitis C and tuberculosis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JJ, Bazazi AR, Altice FL, Mohamed MN, Kamarulzaman A. Absence of antiretroviral therapy and other risk factors for morbidity and mortality in Malaysian compulsory drug detention and rehabilitation centers. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham NM, Nelson KE, Solomon L, Bonds M, Rizzo RT, Scavotto J, et al. Prevalence of tuberculin positivity and skin test anergy in HIV-1-seropositive and -seronegative intravenous drug users. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes CZ, Hwang LY, Williams ML, Austin CM, Graviss EA. Tuberculosis infection in drug users: Interferon-gamma release assay performance. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2007;11:1183–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LY, Grimes CZ, Beasley RP, Graviss EA. Latent tuberculosis infections in hard-to-reach drug using population-detection, prevention and control. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2009;89(Suppl 1):S41–S45. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792(09)70010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin AH, Berg KM, Li X, Hidalgo J, Arnsten JH. Rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial of directly observed hepatitis C treatment delivered in methadone clinics. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2011;11:315. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, Woodson T, Lau B, Olsen Y, et al. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152:704–711. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis B, Al-Darraji HA, Wickersham JA, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2013. Prevalence of tuberculosis symptoms and latent tuberculosis infection among prisoners in Northeastern Malaysia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Althoff AL, Altice FL. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013. State-of-the-art care for HIV-infected people who use drugs: Evidence-based approaches to overcoming healthcare disparities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Aguilera E, Andersson N, Harris E, Mitchell S, Hamel C, Shea B, et al. Risk factors associated with recent transmission of tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2009;13:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor PG, Shi JM, Henry S, Durante AJ, Friedman L, Selwyn PA. Tuberculosis chemoprophylaxis using a liquid isoniazid-methadone admixture for drug users in methadone maintenance. Addiction. 1999;94:1071–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.947107112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms G, Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M. Financing the Millennium Development Goals for health and beyond: Sustaining the ‘Big Push’. Global Health. 2010;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman DC, Gourevitch MN, Trinh C, Salomon N, Horn L, Des Jarlais DC. Cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis screening and observed preventive therapy for active drug injectors at a syringe-exchange program. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:550–567. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack HA, D’Aunno T, Lamar B. Outpatient substance abuse treatment and HIV prevention: An update. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiza S, Rampal KG, Tahir A. Prevalence and risk factors of latent tuberculosis infection among health care workers in Malaysia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2011;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Kamarulzaman A, Sran SK. Malaysia and harm reduction: The challenges and responses. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restum ZG. Public health implications of substandard correctional health care. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1689–1691. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles RR, Reyes JC, Colon HM, Matos TD, Vila Perez L, Marrero CA. Prevalence and correlates of anergy among drug users in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28:509–513. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J, Rudnick D, Slifer M, Agins B, Heiner K, Birkhead G. Co-located substance use treatment and HIV prevention and primary care services, New York State, 1990–2002: A model for effective service delivery to a high-risk population. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84:226–242. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9137-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusen ID, Yuan L, Millson ME. Prevalence of mycobacterium tuberculosis infection among injection drug users in Toronto. CMAJ. 1999;160:799–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruutel K, Loit HM, Sepp T, Kliiman K, McNutt LA, Uuskula A. Enhanced tuberculosis case detection among substitution treatment patients: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4:192. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon N, Perlman DC, Friedmann P, Ziluck V, Des Jarlais DC. Prevalence and risk factors for positive tuberculin skin tests among active drug users at a syringe exchange program. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2000;4:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten JN, Driver CR, Munsiff SS, Kaye K, Rubino MA, Gourevitch MN, et al. Effectiveness of isoniazid treatment for latent tuberculosis infection among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected injection drug users in methadone programs. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37:1686–1692. doi: 10.1086/379513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DC, Paz EA, Mohle-Boetani JC, Fallstad R, Black RL, Chin DP. Tuberculosis prevention in methadone maintenance clinics. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;160:178–185. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9810082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylla L, Bruce RD, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and drug treatment services. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Kamarulzaman A, Liam CK, Lee TC. Tuberculin skin testing among healthcare workers in the University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2002;23:584–590. doi: 10.1086/501975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Economic Planning Unit Prime Minister’s Department. Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011–2015. Putrajaya: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Tuberculosis control in prisons: A manual for programme managers (Geneva) 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Policy guidelines for collaborative TB and HIV services for injecting and other drug users: An integrated approach. WHO Press; Geneva: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Assessment of compulsory treatment of people who use drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam: An application of selected human rights principles. WHO Western Pacific Regional Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global tuberculosis control: WHO report 2011. WHO Press; Geneva: 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Scale-up of harm reduction in Malaysia. WHO Press; Geneva: 2011b. Good practices in Asia: Effective paradigm shifts towards an improved national response to drugs and HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. WHO Press; Geneva: 2011c. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Use of tuberculosis interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) in low- and middle-income countries: Policy statement. WHO Press; Geneva: 2011d. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]