Abstract

Along with molecular abnormalities (mutations in JAK2, Calreticulin (CALR) and MPL genes), chronic inflammation is the major hallmark of Myelofibrosis (MF). Here, we investigated the in vitro effects of crucial factors of the inflammatory microenvironment (Interleukin (IL)-1β, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α, Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 and ATP) on the functional behaviour of MF-derived circulating CD34+ cells.

We found that, regardless mutation status, IL-1β or TNF-α increases the survival of MF-derived CD34+ cells. In addition, along with stimulation of cell cycle progression to the S-phase, IL-1β or TNF-α ± TIMP-1 significantly stimulate(s) the in vitro clonogenic ability of CD34+ cells from JAK2V617 mutated patients. Whereas in the JAK2V617F mutated group, the addition of IL-1β or TNF-α + TIMP-1 decreased the erythroid compartment of the CALR mutated patients. Megakaryocyte progenitors were stimulated by IL-1β (JAK2V617F mutated patients only) and inhibited by TNF-α. IL-1β + TNF-α + C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) ± TIMP-1 highly stimulates the in vitro migration of MF-derived CD34+ cells. Interestingly, after migration toward IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1, CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F mutated patients show increased clonogenic ability.

Here we demonstrate that the interplay of these inflammatory factors promotes and selects the circulating MF-derived CD34+ cells with higher proliferative activity, clonogenic potential and migration ability. Targeting these micro-environmental interactions may be a clinically relevant approach.

Keywords: circulating CD34+ cells, myelofibrosis, inflammatory microenvironment, migration, survival

INTRODUCTION

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a life-threatening chronic myeloproliferative neoplasia (MPN) of the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) clinically characterized by progressive anemia, splenomegaly and constitutional symptoms and by an increased risk to develop acute leukemia (AL). It can arise de novo (primary MF; PMF) or can evolve from Polycythemia Vera (PV; PPV MF) or Essential Thrombocythemia (ET; PET MF) [1–3].

Approximately 50 to 60% of MF patients carry a mutation in the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene, while 20–25% of patients show recurrent mutations in the Calreticulin (CALR) and an additional 5 to 10% have activating mutations in the myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (MPL) gene. Around 10% of patients have non-mutated JAK2, MPL and CALR genes (“triple negative”). Regardless of molecular status, all patients have a deregulation in the JAK/STAT signalling [4–9].

Besides molecular abnormalities, the inflammatory microenvironment has emerged in the last few years as a key-player in MF pathogenesis [10]. Abnormal expression and activity of several cytokines involved in inflammation and immunoregulation are associated with MF [11] and correlate with more severe marrow fibrosis [12, 13], worsening systemic symptoms [14] and decreased survival [15]. Also, the constitutive mobilization of CD34+ cells into the peripheral blood has been associated with profound alterations in the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)/C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) axis [16–18]. Up-regulated production of proinflammatory cytokines by HSPCs and surrounding stromal cells generates a microenvironment that selects for the malignant clone [11, 19–23].

Interestingly, HSPCs actively sense pro-inflammatory factors [24]. However, the key players linking inflammation and cancer in MF are still to be defined. Particularly, the plasma levels of Interleukin (IL)-1β, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 are increased in MF patients [5, 15, 25], but their contribution to disease pathogenesis in MF has been poorly [26] or never investigated. This is also true for the extracellular ATP nucleotide [27]. Under inflammatory conditions, IL-1β stimulates leukocytosis and thrombocytosis by inducing various cytokines (i.e. Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor, IL-6) that are overexpressed in MF; also, IL-1β regulates the survival/proliferation of AL cells [27–30]. IL-1β has been recognized as the main trigger for neural damage and Schwann cell death caused by bone marrow mutant HSPC. Notably, mutant-HSPC-driven niche damage seems to critically contribute to MPN pathogenesis [31]. TNF-α promotes survival of human quiescent bone marrow-derived CD34+ Burst Forming Unit-Erythrocyte (BFU-E) and facilitates the clonal expansion of JAK2V617F-positive cells in MPNs [26, 32]. TIMP-1, through receptor (CD63) binding, promotes cell survival, differentiation and migration; also, TIMP-1 displays cytokine-like features in the HSPC compartment [33–35]. It was initially found to enhance the proliferation of erythroid cells [36]; also, we recently demonstrated that TIMP-1 increases the clonogenic efficiency of normal CB-derived progenitor cells [37]. Finally, extracellular nucleotides, mainly ATP, are important mediators in inflammation and modulation of cell proliferation, migration and death, including AL CD34+ stem/progenitor cells [24, 37–41].

Here, we addressed the functional effects of these pro-inflammatory factors on the in vitro behaviour of HSPCs derived from MF patients, with the aim to investigate their putative role in disease pathogenesis.

RESULTS

Regardless of mutation status, the plasma levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and TIMP-1 are increased in MF patients

To evaluate the pro-inflammatory profile, selected plasma cytokines were measured. Compared with controls, IL-1β, TNF-α and TIMP-1 plasma levels were significantly increased in MF patients (regardless of IPSS risk stratification values) (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C). We found a trend, albeit not statistically significant (p = 0.06), toward increased IL-1β plasma levels in CALR mutated patients. Targeting TNF-α and TIMP-1, no significant differences were observed between JAK2V617F and CALR mutated groups.

Figure 1. Regardless mutation status, the plasma levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and TIMP-1 are increased in MF patients.

IL-1β (A), TNF-α (B) and TIMP-1 (C) plasma levels were measured by ELISA in MF patients. (n = 26; JAK2V617F positive n =16; CALR positive n = 10) and healthy controls (n = 15). Compared with controls, cytokines plasma levels were significantly increased in MF patients. Of note, there was no significant difference between JAK2V617F or CALR mutated patients. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (**p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001).

Selected subsets of circulating HSPCs are expanded in MF patients

To determine the extent of the circulating HSPCs compartment according to mutations, we phenotypically analysed the whole blood of MF patients.

Irrespective of mutation status, the mean number of circulating CD34+ cells was significantly higher in MF patients than in controls (p ≤ 0.0001). No significant differences were observed between the two mutated groups (Figure 2A). Of note, the number of CD34+ cells correlated with IPSS risk in JAK2V617F mutated patients (r = 0.88; p = 0.02; data not shown).

Figure 2. Selected subsets of circulating HSPCs are expanded in MF patients.

The circulating absolute number of MF (total (n = 30) and subdivided into JAK2V617F (n = 20) or CALR (n = 10) mutated groups) and CB (n = 10) CD34+ cells coexpressing the CD133, CD49d, CD47, CD44, CD63, CD184 and CD41 antigens together with the CD34+ CD38− subset are shown (A–I). All subsets were increased in MF patients as compared with the CB counterparts. No significant differences were observed between the two mutated groups, except the CD34+ CD63+ and the CD34+ CD41+ cells of CALR mutated patients which were significantly increased as compared with the JAK2V617F counterparts. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001).

Along with CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD133+ cells (Figure 2B, 2C), circulating CD34+ cells co-expressing adhesion molecules (CD49d, CD47 and CD44; Figure 2D–2F) were also significantly increased in MF patients. Once again, no significant difference was observed between the two mutated groups.

The median number of circulating MF-derived CD34+ cells co-expressing the TIMP-1 (CD63) or the CXCL12 receptor (CD184; CXCR4) was significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively) than the CB counterparts (Figure 2G, 2H). CALR mutated patients showed increased number of circulating CD34+CD63+ and CD34+CD184+ cells compared to JAK2V617F mutated patients (p ≤ 0.01 for CD34+CD63+) or the CB-counterparts (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05, respectively). CD34+CD63+ cells of JAK2V617Fmutated patients were also increased compared with the CB-derived cells (p ≤ 0.05).

As shown in Figure 2I, circulating megakaryocyte (MK) progenitors (CD34+CD41+) were also significantly increased (p ≤ 0.01). CALR mutated patients showed increased number of CD34+CD41+ cells compared to JAK2V617F mutated patients (p ≤ 0.01 ) or the CB-counterparts (p ≤ 0.001).

Of note, except of the decreased expression of CD184 in MF cells, the analysis of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD133, CD63, CD41, CD49d, CD44 and CD47 antigens on the CD34+ cells did not reveal any difference between patients and controls or between the two mutated groups (data not shown).

These data demonstrate that in MF, irrespective of mutation status, there is an in vivo expansion of the HSPCs compartment. However, the CALR mutated patients show an increased number of circulating CD34+CD63+ and CD34+CD41+ cells compared to the JAK2V617F mutated counterparts.

Survival of CD34+ cells from MF patients is increased by IL-1β and TNF-α

To investigate whether inflammatory signals may regulate the survival of HSPCs, CD34+ cells from MF patients or CB were in vitro cultured with the selected pro-inflammatory factors, alone or in combination, at concentrations previously shown to be effective in dose-response experiments (Supplementary Figure 1).

We firstly assessed the effects of factors alone on the in vitro survival of CD34+ cells. As shown in Figure 3A, the survival of CD34+ cells from MF patients was significantly promoted by IL-1β or TNF-α as compared with the CB CD34+ cells (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05, respectively) or with the untreated MF cells (p ≤ 0.001 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively). No significant differences in survival were observed between the two mutated groups in all tested conditions (data not shown).

Figure 3. Survival of CD34+ cells from MF patients is increased by IL-1β and TNF-α.

(A) CD34+ cells from MF patients (n = 20) or CB (n = 8) were in vitro treated for 4 days with factors alone and the percentage of cell viability was assessed after Annexin V/PI staining, as described in Methods. At variance with CB-derived cells, TNF-α and IL-1β alone significantly stimulated the survival of MF-derived CD34+ cells as compared with untreated cells and the CB-derived counterparts. Conversely, ATP and TIMP-1 were ineffective in normal and diseased cells.(B) In selected experiments, before Annexin V/PI staining, MF- (n = 10) and CB- (n = 6) derived CD34+ cells were also labeled with a MoAb against the human CD38 antigen and the CD34+ CD38− cells were gated and cell viability was analyzed. Once again, multiple combinations of cytokines with IL-1β or TNF-α significantly stimulated the survival of MF- and CB-derived CD34+ CD38− cells. Notably, this was not true for ATP+ TNF-α+ TIMP-1. No differences were observed between MF patients and CB. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. (**p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001 vs untreated cells (CTR)) (#p ≤ 0.05; ##p ≤ 0.01 vs CB).

As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, the combinations of factors two-by-two significantly promoted the MF-derived CD34+ cells survival as compared with untreated cells. However, no significant differences in cell viability were observed as compared with factors alone. Interestingly, the two by two combined factors did not significantly enhance the survival of CB-derived CD34+ cells, except for IL-1β + TNF-α (p ≤ 0.01). Comparing MF vs CB-derived cells, the survival of MF CD34+ cells was significantly enhanced by IL-1β + TIMP-1 (p ≤ 0.01) and IL-1β + ATP (p ≤ 0.01).

When multiple factors were combined no significant differences were observed between MF and CB-derived CD34+ cells. Only TNF-α + TIMP-1 + ATP significantly promoted the survival of JAK2V617F CD34+ cells as compared with the CALR (p ≤ 0.01) or CB counterparts (p ≤ 0.001) (data not shown).

When we analyzed the CD34+ CD38− cells (Figure 3B), we found that multiple factors combinations (particularly those including IL-1β) significantly stimulated the cell survival of MF and CB-derived cells as compared with untreated cells. However, no significant differences were observed between patients/controls (Figure 3B) or the two mutated groups (data not shown)

Taken together these data demonstrate that, regardless of mutation status, the survival of MF-derived CD34+ cells is highly stimulated by the in vitro treatment with IL-1β or TNF-α. Combinations of pro-inflammatory factors do not have synergistic effects.

Clonogenic output of circulating MF-derived CD34+ cells is positively enhanced by IL-1β + TNF-α ± TIMP-1 combinations

To analyse the functional role of the selected pro-inflammatory cytokines on HSPCs, we investigated their effects on the clonogenic output of circulating MF and CB-derived CD34+ cells.

Factors alone did not induce a significant CFU-C growth from MF CD34+ cells (data not shown). However, when MF-derived CD34+ cells were tested in the presence of combinations of factors two-by-two, the IL-1β + TIMP-1 combination was the only one effective in stimulating the CFU-C growth as compared with untreated cells (p ≤ 0.05) or CB-derived CD34+ cells (p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 4A). IL-1β + TNF-α and IL-1β + TIMP-1 significantly promoted the BFU-E growth of the MF-derived CD34+ cells as compared with the untreated samples and the CB counterparts. The CFU-GM growth was positively enhanced by IL-1β + TIMP- 1 (Supplementary Figure 3A, 3B). Of note, when combinations of multiple factors were tested, only IL-1β + TNF-α + TIMP-1 significantly promoted the CFU-C growth (p ≤ 0.05) of CD34+ cells from CB (data not shown).

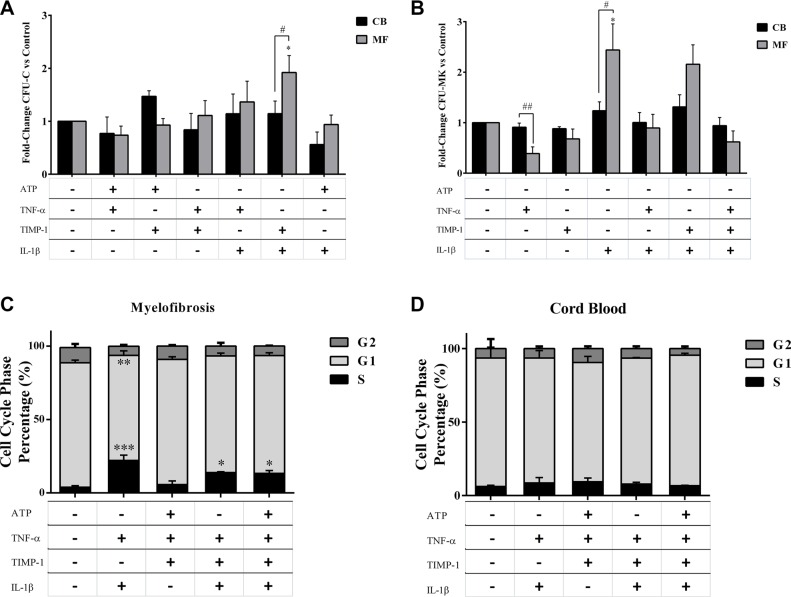

Figure 4. Proliferation of circulating MF-derived CD34+ cells is positively enhanced by IL-1β + TNF-α ± TIMP-1 combinations.

Circulating CD34+ cells were isolated from MF patients (n = 20) and CB units (n = 8) and cultured in the presence of the selected two-by-two pro-inflammatory factors. After 14 days, the total CFU-C output was assessed as described in Methods (A). Circulating CD34+ cells were isolated from MF patients (n = 10) and CB units (n = 8) and cultured in the presence or absence of inflammatory factors alone or combined. After 12 days, the CFU-MK growth was assessed as described in Methods (B). The results are expressed as growth fold change versus untreated CTR samples. (A) The clonogenic output of the MF-derived CD34+ cells was significantly stimulated by the IL-1β + TIMP-1 combination as compared with untreated cells or the CB-derived counterparts. No other combinations of factors two-by-two were effective. The mean number of colonies in MF-derived and CB-derived untreated samples was 59 ± 8 and 63 ± 6, respectively. (B) The MF-derived CFU-MK growth was significantly inhibited by TNF-α. By contrast, IL-1β has stimulatory activity on MK colony formation. Factors in combination did not significantly modify the growth of patients/CB CFU-MK as compared with factors alone. Factors alone or in combination did not significantly modify the CFU-MK growth of the CB counterparts. The mean number of CFU-MK in MF- and CB-derived untreated samples was 26 ± 11 and 46 ± 10, respectively. In (C and D ) are shown the results of cell-cycle analysis of MF-derived (n = 10) and CB-derived (n = 8) CD34+ cells after in vitro incubation for 24 hours in the presence or absence of various combinations of pro-inflammatory factors. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells in different phases of the cell cycle. IL-1β plus TNF-α highly promote cell cycling of CD34+ cells from MF patients. IL-1β + TNF-α + TIMP-1 and IL-1β + TNF-α + TIMP-1 + ATP were also effective (C). Conversely, no significant differences were observed when CB-derived cells were analysed (D). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001 vs untreated cells) (#p ≤ 0.05; ##p ≤ 0.01 vs CB).

As shown in Figure 4B, when the growth of MK progenitors was investigated in the presence of inflammatory factors alone, we found that, at variance with CB, the MF-derived CFU-MK growth was significantly inhibited by TNF-α. By contrast, IL-1β has stimulatory activity on MK colony formation. Factors in combination did not significantly modify the growth of patients/CB pure CFU-MK as compared with factors alone.

We also examined the cell-cycle profile of MF-derived and CB-derived CD34+ cells after in vitro exposure to the cytokines. We found that most of the untreated CD34+ cells from MF patients were in a dormant state. Factors alone did not significantly increased the percentage of CD34+ cells in S phase as compared with untreated cells, both in MF patients and CB (data not shown). Conversely, in MF patients, irrespective of mutation status, cell-cycle progression was observed in presence of various cytokines combinations, with the notable exception of ATP + TNF-α + TIMP-1 (Figure 4C, 4D).

Opposite effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on clonogenic potential of CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F or CALR mutated patients

When clonogenic potential was analysed according to mutation status and in the presence of pro-inflammatory factors alone, no differences were observed between the two mutated groups. Colony composition analysis demonstrated that only IL-1β enhanced the erythroid compartment of the JAK2V617F mutated group (Supplementary Figure 4A and 4B).

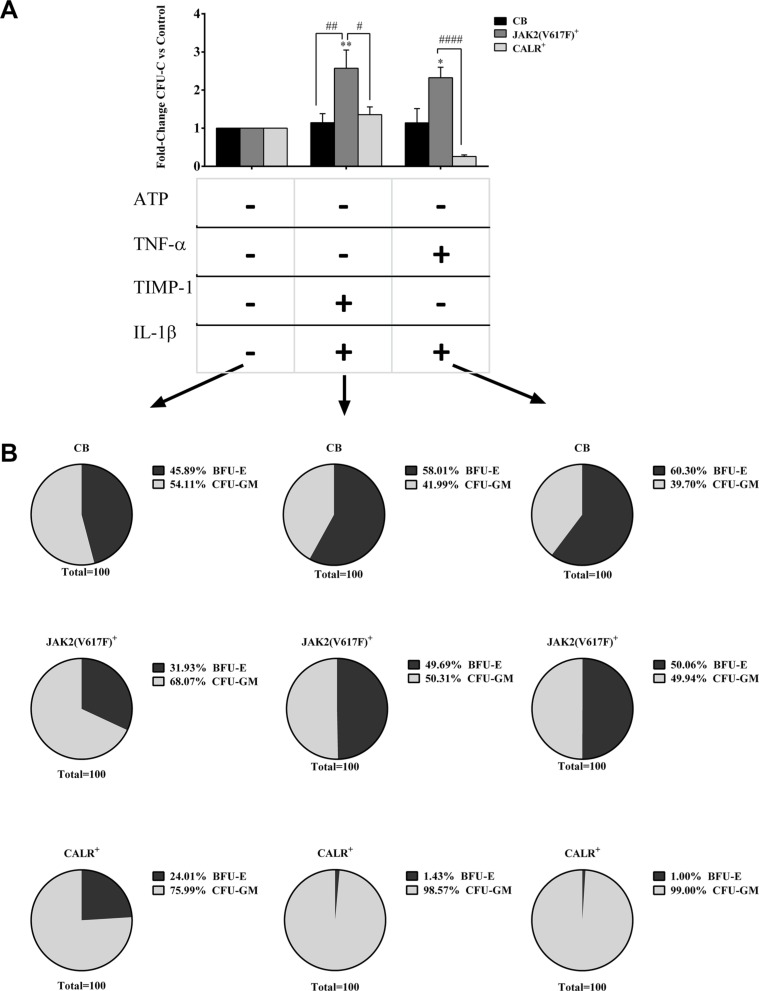

By contrast, (Figure 5A), the combination of IL-1β + TIMP-1 and IL-1β + TNF-α significantly promoted the CFU-C growth of JAK2V617F mutated patients compared with the CALR mutated counterparts. Similar results were obtained when CFU-GM and BFU-E growth were distinctly analysed (data not shown).

Figure 5. Opposite effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on cells from JAK2V617F or CALR mutated patients.

(A) When clonogenic activity was analyzed according to mutation status, the CFU-C growth of JAK2V617F mutated patients was significantly up-regulated by IL-1β + TIMP-1 and IL-1β + TNF-α as compared with untreated control samples, the CALR mutated counterparts and the CB-derived cells (only IL-1β + TIMP-1). The results are expressed as growth fold change versus untreated CTR samples. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01 vs untreated cells) (#p ≤ 0.05; ##p ≤ 0.01; ####p ≤ 0.0001 vs CB-derived cells) (B) When colony composition was analyzed according to mutation status, we found that the erythroid compartment of the untreated samples was reduced in both mutated groups as compared with the CB counterparts. However, no significant differences were observed between the two mutated groups. Interestingly, in the JAK2V617F mutated group, the addition of IL-1β + TIMP-1 and IL-1β + TNF-α enhanced the erythroid compartment as compared with untreated samples. Conversely, some cytokines combinations significantly impaired BFU-E growth in CALR mutated patients. The results are expressed as mean percentage of CFU-GM/BFU-E as compared with the total CFU-C count.

When colony composition was analysed according to mutation status (Figure 5B), both mutated groups showed reduced BFU-E growth of the untreated samples as compared with the CB counterparts. Interestingly, in the JAK2V617F mutated group, the addition of different combinations of pro-inflammatory factors enhanced the erythroid compartment as compared with untreated samples. Conversely, some cytokines combinations significantly decreased BFU-E growth in CALR-mutated patients.

Multiple combinations did not significantly modified the clonogenic activity and colony composition of the two mutated groups (data not shown).

When we analysed the percentage of JAK2V617F and CALR mutant colonies in the absence or presence of IL-1β + TNFα, we found that the percentage of JAK2V617F, but not CALR, mutated colonies was increased (data not shown).

MK progenitors of JAK2V617F mutated patients were highly stimulated by IL-1β alone. By contrast, TNF-α significantly inhibited the CFU-MK growth of both JAK2V617F and CALR mutated patients as compared with CB counterparts (Supplementary Figure 5).

Taken together these results demonstrate that the hemopoietic function of MF-derived CD34+ cells is highly promoted by the IL-1β or TNF-α ± TIMP-1 combinations, even though TNF-α alone show inhibitory effects on MK progenitors. Interestingly, whereas in the JAK2V617F mutated group, the addition of various combinations of growth factors decreased the erythroid compartment of the CALR mutated patients.

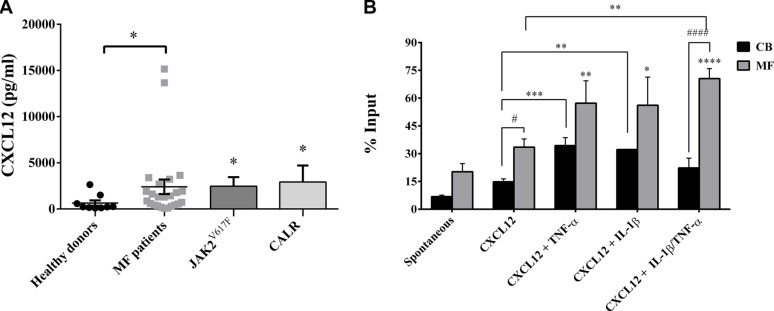

IL-1β and TNF-α significantly promote migration of MF-derived CD34+ cells showing enhanced clonogenic ability after migration in JAK2V617F mutated patients

To evaluate whether selected pro-inflammatory factors may differentially regulate the migratory ability of HSPCs from MF patients, we firstly analyzed the plasma concentration of CXCL12. CXCL12 plasma level was markedly higher in patients than in controls, either total (p ≤ 0.05) or subdivided according to mutation status (JAK2V617F p ≤ 0.05; CALR p ≤ 0.05). Conversely, no significant differences were observed between the two mutated groups (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. IL-1β and TNF-α significantly increases migration of MF-derived CD34+ cells.

(A) CXCL12 plasma levels of MF patients (total n =24; JAK2V617F mutated patients n = 16; CALR mutated patients n = 8) and controls (n = 10). Regardless mutation status, CXCL12 concentration was significantly higher in MF patients (*p ≤ 0.05 vs controls). (B) When cells were migrated toward CXCL12 alone, an increased migration ability was observed in MF-derived (n = 15) CD34+ cells as compared with the CB-derived (n = 8) counterparts. The addition of inflammatory factors alone (IL-1β/TNF-α) plus CXCL12 significantly increased the migratory behaviour of MF-derived CD34+ cells as compared with CXCL12 alone. IL-1β + TNF-α synergistically enhanced the migratory behaviour of CD34+ cells as compared with spontaneous migration (****p < 0.0001), CXCL12 alone (**p <0.001) and the CB-counterpart (####p <0.0001). Results are expressed as mean percentages ± SEM of input. (**p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001 vs CXCL12 alone for CB-derived CD34+ cells) (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ****p < 0.0001 vs spontaneous migration for MF-derived CD34+ cells) (#p ≤ 0.05; ####p <0.0001 vs CB).

To mirror the in vivo pattern of MF, we set up in vitro migration experiments in the presence of the identified inflammatory factors and CXCL12. The migration rate of MF- or CB-derived CD34+ cells toward inflammatory factors alone (without CXCL12) was not significantly different from that of untreated cells (data not shown).

As shown in Figure 6B, CXCL12 significantly increased the migratory behaviour of MF-derived CD34+ cells as compared with CB counterparts (p ≤ 0.05). The addition of IL-1β or TNF-α + CXCL12 shows a trend toward increased migration of CD34+ cells from MF patients, but doesn't reach statistical significance. At variance with CB derived cells, the addition of both cytokines significantly increased the migratory potential of CD34+ cells from MF patients (p ≤ 0.01). No differences were observed between the two mutated groups (data not shown).

The addition of TIMP-1 and ATP alone or inflammatory factors two by two in the presence of CXCL12 did not significantly increase the migration ability of MF-derived CD34+ cells as compared with CXCL12 alone (data not shown). The migratory behavior of the MF-derived CD34+ cells toward multiple combinations of factors was significantly enhanced as compared with the CB-derived counterparts in all tested combinations. Conversely, CB-derived CD34+ cells were almost insensitive (Supplementary Figure 6).

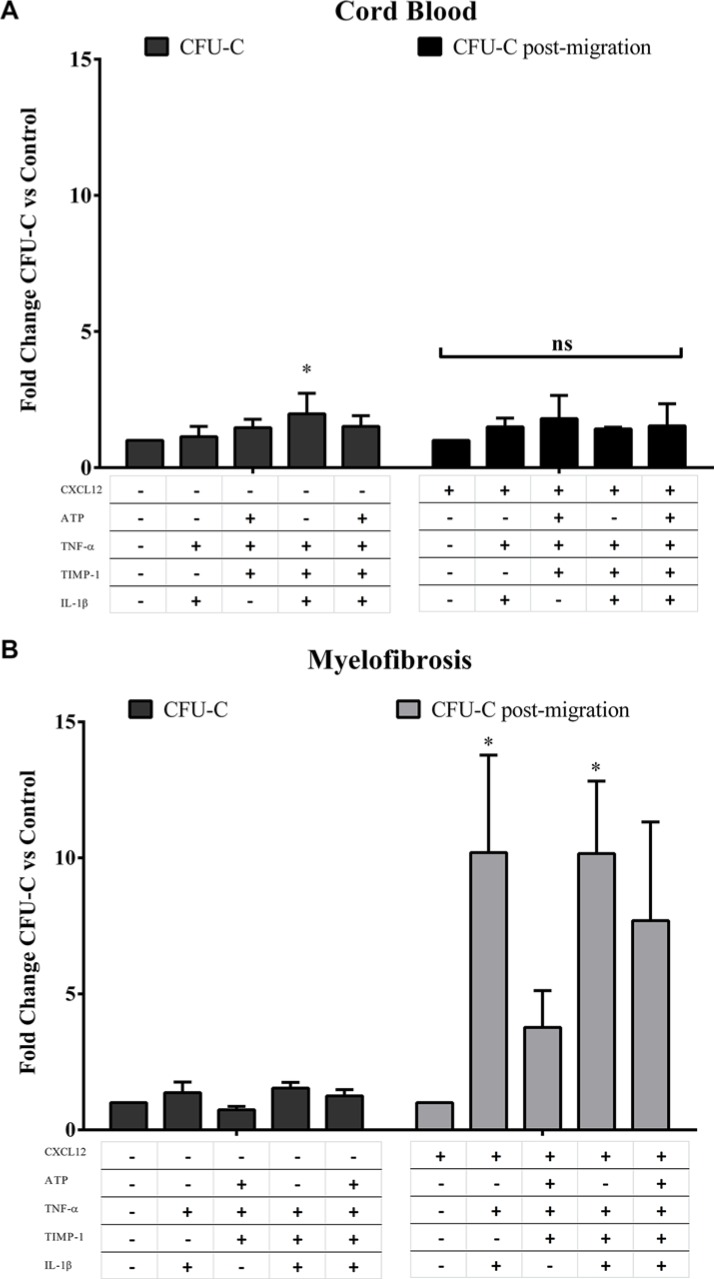

To evaluate whether migrated cells toward various pro-inflammatory gradients show different hemopoietic function, we also tested the clonogenic potential of CD34+ cells from MF patients or CB after migration toward CXCL12 alone or CXCL12 plus various combinations of factors (Figure 7A, 7B). Interestingly, at variance with the CFU-C growth of unmigrated HSPCs from MF patients, IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 and IL-1β + TNF-α + TIMP-1 + CXCL12 selected a subset of MF-derived CD34+ cells with higher clonogenic potential as compared with CXCL12 alone (p ≤ 0.05, respectively) (Figure 7B). Conversely, the clonogenic output of CB-derived CD34+ cells after migration toward various combinations of pro-inflammatory factors was unaffected (Figure 7A). Notably, according to mutation status, the CFU-C post migration assay demonstrated once again that various combinations of pro-inflammatory factors significantly stimulate the clonogenic ability of migrated CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F, but not CALR, mutated patients (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 7. The clonogenic output of MF-derived CD34+ cells after migration toward IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1 is potently enhanced.

Panels (A and B) show the clonogenic potential of CB-derived (A; n = 6) and MF-derived CD34+ cells (B; n = 14) at baseline with or without various combinations of pro-inflammatory factors (CFU-C) and after migration toward CXCL12 alone or various combinations of pro-inflammatory factors + CXCL12 (CFU-C post-migration). After migration toward IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1, the MF-derived, but not CB-derived, CD34+ cells show significantly increased clonogenic potential. Results are expressed as mean fold change of CFU-C ± SEM. (*p ≤ 0.05 vs untreated cells (A) and CXCL12 alone (B)).

When the number of granulocyte and erythroid colonies were analysed individually, only BFU-E growth was significantly increased with respect to controls (p ≤ 0.05) after cells were migrated toward IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1. Of note, IL-1β + TNF-α + TIMP-1 + CXCL12 significantly stimulated also CFU-GM growth as compared with CXCL12 alone (p ≤ 0.05) (data not shown).

Taken together these results demonstrate that, irrespective of mutation status, IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1 selectively enhance the migratory ability of MF-derived CD34+ cells. Interestingly, IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1 promotes and selects the circulating HSPCs of JAK2V617F mutated patients with higher clonogenic potential.

DISCUSSION

Here, we evaluated the in vitro effects of four main crucial factors of the inflammatory microenvironment (IL-1β, TNF-α, TIMP-1 and ATP) on survival, clonogenic output and migration ability of MF HSPCs.

First, this study demonstrates that, regardless of mutation status, IL-1β, TNF-α and TIMP-1 are increased in the plasma of MF patients and the presence of IL-1β, TNF-α ± TIMP-1 confers a survival advantage of MF-derived HSPCs. Second, HSPCs from JAK2V617F show in vitro enhanced proliferation over untreated cells and the CB counterparts in response to IL-1β, TNF-α ± TIMP-1 exposure (alone or, mostly, in combination). Accordingly, IL-1β + TNF-α stimulates cell cycle progression of MF-derived CD34+ cells to the S-phase. Third, IL-1β + TNF-α combination promotes the in vitro migration of MF-derived HSPCs. Interestingly, after migration toward IL-1β + TNF-α + CXCL12 ± TIMP-1, MF-derived CD34+ cells show increased clonogenic ability as compared with CXCL12 alone or the CB counterparts. This finding was mainly due to stimulation of the clonogenic growth of HSPCs from JAK2V617F mutated patients.

TNF-α has already been shown to facilitate clonal expansion of JAK2V617F-positive cells in MF [26]. The results of this study provide new evidences that, in addition to TNF-α, IL-1β and TIMP-1 promote the in vitro maintenance of the HSPCs.

Mutation status is associated with dysregulated hemopoietic function (clonogenic output and colony composition) of MF-derived CD34+ cells in presence of IL-1β + TNF-α ± TIMP-1. Specifically, when pro-inflammatory factors were added in culture, CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F mutated patients showed increased clonogenic potential and increased size of the erythroid progenitors compartment as compared with the CALR-mutated counterparts. Along with the CFU-C growth, IL-1β stimulates the in vitro growth of MK progenitors of JAK2V617F mutated patients only. Consistent data on single cell assays suggested that HSC self-renewal capacity is negatively affected by JAK2V617F, but progenitor cells have increased proliferation capacity [42]. In addition, these findings can be related to the fact that JAK2V617F mutant, in contrast with the CALR counterpart, activates not only the MK cell line but also the erythroid and granulocytic lineages [43].

Despite increased frequency of MK progenitors (CD34+CD41+ cells) in the PB of CALR mutated patients, we clearly demonstrate that the hemopoietic function of CD34+ cells from CALR mutated patients is unmodified (megakaryocytic compartment) or significantly inhibited (erythroid compartment) by IL-1β or various combinations of inflammatory factors including IL-1β. It is therefore likely that these functional abnormalities may contribute to explain the lower haemoglobin concentration that is displayed by CALR-positive patients compared to JAK2V617F-mutated patients [8]. Interestingly, at variance with JAK2V617F, CALR mutants moderately activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, a critical determinant of erythropoiesis and megakaryocytopoiesis [43–46].

Of note, we also found increased number of circulating CD34+CD63+ cells in MF. However, despite TIMP-1 alone was ineffective, various combinations including TIMP-1 increased the proliferation/migration of MF-derived CD34+ cells. This finding was not due to upregulated expression of CD63 receptor on MF-derived CD34+ cells after exposure to IL-1β and/or TNF-α (data not shown). It is therefore likely that downstream intracellular signaling pathways are hyperactivated and stimulate clonogenic activity.

Overall, our data indicate that the in vitro behavior of the MF-derived HSPCs can be upregulated by regulatory signals provided by the microenvironment and, specifically, through the cooperation between various pro-inflammatory factors. Therefore, the increased number of HSPCs in the peripheral blood of MF may be due not only to the displacement of HSPCs from bone marrow into peripheral blood, but also to the proliferative/survival signals coming from the pro-inflammatory factors within the peripheral blood niche. As a consequence, the pro-inflammatory microenvironment emerges as central site for cell division and proliferation.

In conclusion, the in vitro interplay between identified pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are abnormally increased, promotes and selects the circulating MF-derived HSPCs with higher proliferative activity, clonogenic potential and migration ability. Thus, it is likely that the in vivo inflammatory niche plays a key role in the maintenance of the malignant hemopoietic clone. Targeting these inflammatory micro-environmental interactions may be a clinically relevant approach for MF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples

Peripheral blood (PB) was obtained from 10 normal age-matched volunteers and 36 patients with MF in chronic phase. Patients characteristics according to mutational status are shown in Table 1. At the time of the study, patients were at diagnosis (19 cases) or untreated for at least two months. Previous therapies were: hydroxyurea (12 cases) and Ruxolitinib (3 cases). The diagnosis of MF was made according to WHO 2008 criteria [47]. Patients and controls provided written informed consent for the study. This study was approved by the medical Ethical Committee of the University Hospital of Bologna and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. During the last trimester of pregnancy, an increased number of CD34+ HSPC are mobilized from the fetal liver and can be found in the circulating blood, including umbilical cord blood (CB). Therefore, since HSPC trafficking characterizes both the PB of MF patients and CB, we choose this physiological source for comparison. CB collections (14 cases) from normal full-term deliveries were provided by the Cord Blood Bank of the University Hospital of Bologna after written informed consent.

Table 1. Patients characteristics according to mutational status.

| Characteristics | JAK2V617F-mutated patients (no. 23) | CALR mutated patients (no.13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 65 (40–82) | 73 (70–84) | 0.01 |

| Male sex, n° (%) | 12 (52%) | 7 (54%) | 1 |

| Median allele burden, % (range) | 89 (0,4–99) | 56,5 (47–98) | 0.07 |

| Median WBC,×109/L (range) | 8,6 (2,5–157,6) | 6,6 (2,3–16) | 0.48 |

| Median hemoglobin, g/dL (range) | 11,9 (8,6–15,1) | 9,3 (7,7–12,7) | 0.04 |

| Median platelet count, ×109/l (range) | 270 (41–707) | 198 (86–419) | 0.44 |

| High/intermediate 2 IPSS category, n° (%) | 12 (52) | 7 (54) | 1 |

| Unfavorable karyotype, n° (%) | 9 (39) | 3 (23) | 0.46 |

| PMF diagnosis, n° (%) | 14 (61) | 9 (69) | 0.7 |

| BM fibrosis grade ≥ 2, n° (%) | 14 (61) | 13 (100) | 0.03 |

| Patients with splenomegaly, n° (%) | 19 (83) | 10 (77) | 0.7 |

| Median follow-up, months (range) | 45 (1,9–114,9) | 48 (10–136,3) | 0.24 |

Cell isolation

PB, anticoagulated with ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), was obtained from patients/controls. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated from MF and CB samples by stratification on Lympholyte-H 1.077 g/cm3 gradient (Gibco-Invitrogen, Milan, Italy), followed by red blood cell lysis for 15 min at 4°C. MNCs were then processed on magnetic columns for CD34+ cell isolation (mean purity 94% ± 5%) (MACS CD34 Isolation kit; Miltenyi Biotech, Bologna, Italy), as previously described [37].

Plasma levels measurement of selected circulating cytokines

We measured the cytokines plasma levels of patients/controls by ELISA, according to the manufacturer's instructions. EDTA-anticoagulated PB was centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1000 g within 30 minutes of collection. The plasma was then collected and stored at −80°C until quantification. In particular, the TIMP-1 ELISA kit was provided from Boster Immunoleader (Boster Biological Technology Co., Pleasanton, CA, USA) and CXCL12 ELISA kit from Krishgen ByoSistems (Ashley CT, Whittier, CA, USA). The CiraplexTM immunoassay kit/Human 9-Plex Array (Aushon BioSystems, Billerica, MA, USA) was used for the measurement of various cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α.

Phenotype of circulating CD34+ cells

The phenotype of circulating CD34+ cells was evaluated in PB from MF patients and in CB samples by conventional immunofluorescence, as previously described (48). Antibodies used to characterize the CD34+ cells are listed in Supplementary Table 1. A minimum of 1 × 104 CD34+ cells were acquired by flow cytometer BD Accuri C6 (Becton Dickinson). Analysis was performed excluding cellular debris in a SSC/FSC dot plot. The percentage of positive cells was calculated subtracting the value of the appropriate isotype controls. The absolute number of positive cells/mL was calculated as follows: percentage of positive cells × White Blood Cells count/100.

Apoptosis assay

Freshly isolated CD34+ HSPCs (2–5 × 105) from MF patients or CB units were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, with or without IL-1β (1,10 ng/mL), TNF-α (10,100 ng/mL), TIMP-1 (100,300 ng/mL), and ATP (100,1000 μM), alone or in different combinations. After 4 days, cells were stained for 15 min at RT with Annexin-V-FLUOS Staining Kit (Roche, Penzberg, Germany). Samples were then immediately analyzed by BD Accuri C6 (BD Bioscience). Results are expressed as percentage of live cells compared to the whole cells.

Erythroid and granulocytic progenitors assays

MF/CB-derived CD34+ cells were cultured in vitro to achieve hematopoietic cell differentiation and the formation of multi-lineage colony-forming units (CFU-Cs), including colony forming unit-granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) and BFU-E. Specifically, CD34+ cells were seeded in methylcellulose-based medium (human StemMACS HSC-CFU lite w/Epo, Miltenyi Biotech) at 5 × 102 cells/mL in 35-mm Petri dishes in the presence or absence of the selected pro-inflammatory factors: TIMP-1 (100 ng/mL; Thermo Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA), ATP (1000 μM; Sigma Aldrich, Milan, Italy), TNF-α (10 ng/mL; Thermo Scientific) and IL-1β (1 ng/mL; Thermo Scientific), alone or in combination. After 2 weeks of incubation at 37°C in 5% humidified CO2 atmosphere, CFU-C growth was evaluated by standard morphologic criteria using an inverted microscope (Axiovert 40, Zeiss).

Megakaryocytic progenitors assay

Megakaryocytic colonies (Colony Forming Unit-Megakaryocyte (CFU-MK)) were obtained using MegaCult™-C assay (Stem Cell Technologies; Vancouver, BC, Canada), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, 5 × 103 MF/CB-derived CD34+ cells were seeded in a collagen-based medium in double chamber slides in the presence or absence of the inflammatory factors, alone or in combination. Cultures were incubated for 12 days and then dehydrated, fixed and stained with a primary antibody to the MK-specific antigen GPllb/llla (CD41) linked to a secondary biotinylated antibody-alkaline phosphatase avidin conjugated detection system. CFU-MK were counted using a light microscope.

Cell cycle analysis

A total of 106 CD34+ cells was maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 (Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Cells were resuspended in complete medium at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL, and primed for 24 hours with the pro-inflammatory cytokines (1 ng/mL IL-1β, 10 ng/mL TNF-α, 100 ng/mL TIMP-1, 1000 μM ATP), alone or in combination. Treated cells were first permeabilized with NP-40 (15 min at RT) and then labeled with propidium iodide (PI)/RNAse staining kit (BD Bioscience) for 15 min at RT, in the dark. The DNA content was assessed by BD Accuri C6 (BD Bioscience) and results were analyzed by FCS express 4 software.

Changes in the cell-cycle distribution were evaluated using PI. The percentage of cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases was determined by measuring simultaneously the DNA and RNA total cellular content.

Migration assay

Migration of MF/CB purified CD34+ cells was assayed towards a CXCL12 gradient (150 ng/mL) in transwell chambers (diameter 6.5 mm, pore size 8 μm; Costar; Corning), as previously described [38]. Briefly, 50 μl of RPMI 1640 plus 10% FBS containing 0,5 × 105 cells were added to the upper chamber and 150 μl of medium with or without CXCL12 ± IL-1β (1 ng/mL), TNF-α (10 ng/mL), TIMP-1 (100 ng/mL), and ATP (1000 μM) (alone or in combination) were added to the bottom chamber. After overnight incubation at 37°C in 5% humidified CO2 atmosphere, inserts (upper chambers) were removed and cells transmigrated into lower chamber were recovered and counted by Trypan Blue exclusion test in a Neubauer chamber using an inverted microscope (Nikon) with a 10×magnification. The amount of migrated cells was expressed as a percentage of the input, applying the following formula: (number of migrated cells recovered from the lower compartment/total number of cells loaded in the upper compartment) × 100. In addition, migrated cells were assayed in methylcellulose-based medium for their ability to form hematopoietic colonies (as above described).

Mutation analysis

JAK2V617F allele-burden was assessed in granulocyte DNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction–based allelic discrimination assay (ipsogen JAK2 MutaQuant Kit) on 7900 HT Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem) [49]. CALR exon 9 sequencing was performed by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) approach with GS Junior (Roche-454 platform); analysis was carried out with AVA Software (GRCh38 as reference) [50]. Rare CALR mutations identified by NGS were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Individual colonies were harvested at day 12–14 from 3 JAK2V617F and 3 CALR mutated patients (20 individual colonies each condition). Molecular characterization of single colonies was performed on DNA extracted using REPLI-g Single Cell Kit (QIAGEN, Marseille, France), which provides accurate genome amplification from single cells or limited samples with high efficiency. Briefly, 4 μL of cell material (supplied with PBS) were firstly lysed. After denaturation, isothermal amplification reaction was performed and amplified DNA was used for JAK2V617F and CALR mutations assessment, as above described.

Cytogenetic analysis

Chromosome banding analysis was performed on bone marrow cells by standard banding techniques according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. At least 20 metaphases were required. Unfavourable karyotype included complex karyotype or single or two abnormalities including +8, −7/7q-, i(17q), −5%5q-, 12p-, inv(3) or 11q23 rearrangement [51, 52].

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables have been summarized by their median and range, and categorical variables by count and relative frequency (%) of each category. Comparisons of quantitative variables between groups of patients were carried out by the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All p values were considered statistically significant when ≤ 0.05 (2-tailed). Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) and SPSS software (PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago, IL).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL FIGURES AND TABLE

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

GRANT SUPPORT

This research was supported by Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie-Bologna section (BolognAIL), by the University of Bologna (RFO 2013–2014 for L.C. and F.P.) and by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under Grant Agreement n° 306242-NGS-PTL and from Progetto Regione–Università 2012–2014 (L. Bolondi).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleppe M, Levine RL. New pieces of a puzzle: the current biological picture of MPN. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tefferi A, Pardanani A. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: a contemporary review. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:97–105. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervantes F, Arellano-Rodrigo E, Alvarez-Larràn A. Blood cell activation in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2009;94:1484–88. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James C, Ugo V, Casadevall N, Constantinescu SN, Vainchenker W. A JAK2 mutation in myeloproliferative disorders : pathogenesis and therapeutic and scientific prospects. Trend Mol Med. 2005;11:546–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tefferi A, Vainchenker W. Myeloproliferative neoplasms: molecular pathophysiology, essential clinical understanding and treatment strategies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:573–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, Nivarthi H, Rumi E, Milosevic JD, Them NC, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pietra D, Chen D, Vladimer GI, Bagienski K, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2379–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen E, Mullally A. How does JAK2V617F contribute to the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms? Hematology AM Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:268–76. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rumi E, Pietra D, Pascutto C, Guglielmelli P, Martínez-Trillos A, Casetti I, Colomer D, Pieri L, Pratcorona M, Rotunno G, Sant'Antonio E, Bellini M, Cavalloni C, et al. Clinical effect of driver mutations of JAK2, CALR,or MPL in primary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2014;124:1062–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-578435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapper W, Jones AV, Kralovics R, Harutyunyan AS, Zoi K, Leung W, Godfrey AL, Guglielmelli P, Callaway A, Ward D, Aranaz P, White HE, Waghorn K, et al. Genetic variation at MECOM, TERT, JAK2 and HBS1L-MYB predisposes to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6691. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geyer HL, Dueck AC, Scherber RM, Mesa RA. Impact of Inflammation on Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Development. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:284706. doi: 10.1155/2015/284706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasselbalch HC. The role of cytokines in the initiation and progression of myelofibrosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:133–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Bousse-Kerdilès MC, Martyré MC. Dual implication of fibrogenic cytokines in the pathogenesis of fibrosis and myeloproliferation in myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Ann Hematol. 1999;78:437–44. doi: 10.1007/s002770050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tefferi A. Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1255–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Squires M, Harrison CN, Barosi G, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T, Gisslinger H, Passamonti F, Al-Ali HK, Kiladjian J, Marker MT, Mendelson ET, Stalbovskaya V, Cervantes F, et al. The Relationship Between Cytokine Levels and Symptoms in Patients (Pts) With Myelofibrosis (MF) From COMFORT-II, a Phase 3 Study of Ruxolitinib (RUX) Vs Best Available Therapy (BAT) Blood. 2013;122:4070. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tefferi A, Vaidya R, Caramazza D, Finke C, Lasho T, Pardanani A. Circulating interleukin (IL)-8, IL-2R, IL-12, and IL-15 levels are independently prognostic in primary myelofibrosis: a comprehensive cytokine profiling study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1356–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barosi G, Viarengo G, Pecci A, Rosti V, Piaggio G, Marchetti M, Frassoni F. Diagnostic and clinical relevance of the number of circulating CD34(+) cells in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2001;98:3249–55. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu M, Bruno E, Chao J, Huang S, Finazzi G, Fruchtman SM, Popat U, Prchal JT, Barosi G, Hoffman R. MPD Research Consortium. Constitutive mobilization of CD34+ cells into the peripheral blood in idiopathic myelofibrosis may be due to the action of a number of proteases. Blood. 2005;105:4508–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliaccio AR, Martelli F, Verrucci M, Migliaccio G, Vannucchi AM, Ni H, Xu M, Jiang Y, Nakamoto B, Papayannopoulou T, Hoffman R. Altered SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in patients with primary myelofibrosis and in the Gata1 low mouse model of the disease. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:158–71. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasselbalch HC. Perspectives on chronic inflammation in essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis: is chronic inflammation a trigger and driver of clonal evolution and development of accelerated atherosclerosis and second cancer? Blood. 2012;119:3219–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasselbalch HC. Chronic Inflammation as a Promoter of Mutagenesis in Essential Thrombocythemia, Polycythemia Vera and Myelofibrosis. A Human Inflammation Model for Cancer Development. Leuk Res. 2013;37:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lataillade JJ, Pierre-Louis O, Hasselbalch HC, Uzan G, Jasmin C, Martyré MC, Le Bousse-Kerdilès MC. French INSERM and the European EUMNET Networks on Myelofibrosis. Does primary myelofibrosis involve a defective stem cell niche? From concept to evidence. Blood. 2008;112:3026–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-158386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleischman AG. Inflammation as a driver of clonal evolution in Myeloproliferative Neoplasm. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:606819. doi: 10.1155/2015/606819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Bousse-Kerdilès MC. Primary myelofibrosis and the “bad seeds in bad soil” concept. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:S20. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi L, Salvestrini V, Ferrari D, Di Virgilio F, Lemoli RM. The sixth sense: hematopoietic stem cells detect danger through purinergic signaling. Blood. 2012;120:2365–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JC, Novetsky A, Chen C, Novetsky AD. Plasma matrix metalloproteinase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase in patients with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia or idiopathyc primary myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:709–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleischman AG, Aichberger KJ, Luty SB, Bumm TG, Petersen CL, Doratotaj S, Vasudevan KB, LaTocha DH, Yang F, Press RD, Loriaux MM, Pahl HL, Silver RT, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha facilitates clonal expansion of JAK2V617F-positive cells in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:6392–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bours MJ, Dagnelie PC, Giuliani AL, Wesselius A, Di Virgilio F. P2 receptors and extracellular ATP: a novel homeostatic pathway in inflammation. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:1443–56. doi: 10.2741/235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turzanski J, Grundy M, Russel NH, Pallis M. Interleukin-1beta maintains an apoptosis-resistant phenotype in the blast cells of acute myeloid leukaemia via multiple pathways. Leukemia. 2004;18:1662–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Ikezoe T, Nishioka C, Nobumoto A, Yokoyama A. IL-1β inhibits self-renewal capacity of dormant CD34+/CD38- acute myelogenous leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1967–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arranz L, Sánchez-Aguilera A, Martín-Pérez D, Isern J, Langa X, Tzankov A, Lundberg P, Muntión S, Tzeng YS, Lai DM, Schwaller J, Skoda RC, Méndez-Ferrer S. Neuropathy of haematopoietic stem cell niche is essential for myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature. 2014;7(512):78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature13383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Reca R, Zhang J, Machalinski B, Ratajczak MZ. Quiescent CD34+ early erythroid progenitors are resistant to several erythropoietic ‘inhibitory’ cytokines; role of FLIP. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:160–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chirco R, Liu XW, Jung KK, Kim HR. Novel functions of TIMPs in cell signaling. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;7:19414–29. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ries C. Cytokine functions of TIMP-1. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:659–72. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1457-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SY, Kim JM, Cho SY, Kim HS, Shin HS, Jeon JY, Kausar R, Jeong SY, Lee YS, Lee MA. TIMP-1 modulates chemotaxis of human neural stem cells through CD63 and integrin signalling. Biochem J. 2014;459:565–76. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stricklin GP, Welgus HG. Physiological relevance of erythroid-potentiating activity of TIMP. Nature. 1986;321:628. doi: 10.1038/321628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi L, Forte D, Migliardi G, Salvestrini V, Buzzi M, Ricciardi MR, Licchetta R, Tafuri A, Bicciato S, Cavo M, Catani L, Lemoli RM, Curti A. The tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 increases the clonogenic efficiency of human hematopoietic progenitor cells through CD63PI3K/Akt signaling. Exp Hematol. 2015;43:974–985.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi L, Manfredini R, Bertolini F, Ferrari D, Fogli M, Zini R, Salati S, Salvestrini V, Gulinelli S, Adinolfi E, Ferrari S, Di Virgilio F, Baccarani M, et al. The extracellular nucleotide UTP is a potent inducer of hematopoietic stem cell migration. Blood. 2007;109:533–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-035634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Morelli A, Torboli M, Bolognesi G, Baricordi OR. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecole in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemoli RM, Ferrari D, Fogli M, Rossi L, Pizzirani C, Forchap S, Chiozzi P, Vaselli D, Bertolini F, Foutz T, Aluigi M, Baccarani M, Di Virgilio F. Extracellular nucleotides are potent stimulators of human hematopoietic stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:1662–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvestrini V, Zini R, Rossi L, Gulinelli S, Manfredini R, Bianchi E, Piacibello W, Caione L, Migliardi G, Ricciardi MR, Tafuri A, Romano M, Salati S, et al. Purinergic signalling inhibits human acute myeloblastic leukemia cell proliferation, migration and engraftment in immunodeficient mice. Blood. 2012;119:217–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-370775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anand S, Stedham F, Beer P, Gudgin E, Ortmann CA, Bench A, Erber W, Green AR, Huntly BJ. Effects of the JAK2 mutation on the hemopoietic stem and progenitor compartment in human myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:177–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vainchenker W, Constantinescu SN, Plo I. Recent advances in understanding myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia. F1000Res. 2016:5. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chachoua I, Pecquet C, El-Khoury M, Nivarthi H, Albu RI, Marty C, Gryshkova V, Defour JP, Vertenoeil G, Ngo A, Koay A, Raslova H, Courtoy PJ, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor activation by myeloproliferative neoplasm associated calreticulin mutants. Blood. 2016;127:1325–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-681932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bartalucci N, Tozzi L, Bogani C, Martinelli S, Rotunno G, Villeval JL, Vannucchi AM. Co-targetingthe PI3K/mTOR and JAK2 signalling pathways produces synergistic activity against myeloproliferative neoplasms. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:1385–96. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choong ML, Pecquet C, Pendharkar V, Diaconu CC, Yong JW, Tai SJ, Wang SF, Defour JP, Sangthongpitag K, Villeval JL, Vainchenker W, Constantinescu SN, Lee MA. Combination treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms using JAK and pan-class I PI3K inhibitors. J cell Mol Med. 2013;17:1397–409. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, Harris NL, Le Beau MM, Hellström-Lindberg E, Tefferi A, Bloomfield CD. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemoli RM, Catani L, Talarico S, Loggi E, Gramenzi A, Baccarani U, Fogli M, Grazi GL, Aluigi M, Marzocchi G, Bernardi M, Pinna A, Bresadola F, et al. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived hematopoietic and endothelial stem cells after orthotopic liver transplantation and liver resection. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2817–25. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jovanovic JV, Ivey A, Vannucchi AM, Lippert E, Oppliger Leibundgut E, Cassinat B, Pallisgaard N, Maroc N, Hermouet S, Nickless G, Guglielmelli P, van der Reijden BA, Jansen JH, et al. Establishing optimal quantitative-polymerase chain reaction assays for routine diagnosis and tracking of minimal residual disease in JAK2-V617F-associated myeloproliferative neoplasms: a joint European LeukemiaNet/MPN&MPNr-EuroNet (COST action BM0902) study. Leukemia. 2013;27:2032–39. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohlmann A, Klein HU, Weissmann S, Bresolin S, Chaplin T, Cuppens H, Haschke-Becher E, Garicochea B, Grossmann V, Hanczaruk B, Hebestreit K, Gabriel C, Iacobucci I, et al. The Interlaboratory RObustness of Next-generation sequencing (IRON) study: a deep sequencing investigation of TET2, CBL and KRAS mutations by an international consortium involving 10 laboratories. Leukemia. 2011;25:1840–48. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaffer LG, SM, Campbell LJ. ISCN 2009: International System of Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Basel, Switzerland: Karger AG; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, George G, Begna K, Schwager S, Van Dyke D, Hanson C, Wu W, Pardanani A, Cervantes F, Passamonti F, Tefferi A. DIPSS plus. : a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for Primary Myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:392–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.