Abstract

The construction of knockin vectors designed to modify endogenous genes in embryonic stem (ES) cells and the generation of mice from these modified cells is time consuming. The timeline of an experiment from the conception of an idea to the availability of mature mice is at least 9 months. We describe a method in which this timeline is typically reduced to 3 months. Knockin vectors are rapidly constructed from bacterial artificial chromosome clones by recombineering followed by gap-repair (GR) rescue, and mice are rapidly derived by injecting genetically modified ES cells into tetraploid blastocysts. We also describe a tandem affinity purification (TAP)/floxed marker gene plasmid and a GR rescue plasmid that can be used to TAP tag any murine gene. The combination of recombineering and tetraploid blastocyst complementation provides a means for large-scale TAP tagging of mammalian genes.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, protein–protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been studied on a genome-wide level (1–4). This large-scale approach is possible because endogenous, protein-encoding genes in yeast are easily tagged with sequences that facilitate protein complex purification. The high efficiency of homologous recombination in this organism permits modifications of endogenous genes with electroporated PCR products containing only 40 bp of homology. The modified genes are expressed at normal levels; therefore, physiologically relevant protein complexes are formed in vivo and these complexes can be easily purified.

Similar studies have not been performed in mammalian cells because the efficiency of homologous recombination is several orders of magnitude lower. Two novel technologies that have been developed in the past few years make large-scale tagging of mammalian genes possible. The first technology is recombineering. This method utilizes strains of Escherichia coli that contain inducible recombination (red) genes of bacteriophage λ to carry out efficient, homologous recombination between short, terminal homology regions on a PCR product and sequences on a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) (5,6). Several groups have used this technology to construct standard, conditional and knockin gene-targeting vectors for embryonic stem (ES) cell modifications (7,8).

The second technology is ES cell complementation of tetraploid embryos (9–11). This method allows mice to be cloned directly from ES cells. F1 hybrid ES cells are injected into tetraploid blastocysts and implanted into pseudopregnant foster mothers. The animals that are born after 18 days are derived totally from injected cells. If ES cells containing tagged genes are injected, primary tissues could be used directly for protein purification. In this paper, we combine recombineering and ES cell complementation of tetraploid blastocyts to produce knockin mice with a tagged allele in 3 months. The protocol is applicable to any mouse gene and provides a method for large-scale tagging of mouse genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BAC transfer

The Erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF) BAC DNA (75 kb) was purified from the E.coli strain DH10B by the miniprep method (12). Five hundred nanograms of this DNA was electroporated into the E.coli recombineering strain DY380 and chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were obtained. EKLF BAC DNA prepared from DH10B and DY380 was digested with EcoRI, KpnI and SalI and separated on agarose gels to confirm that no DNA rearrangements occurred.

Plasmids

The TAPR plamid was constructed by assembling DNA fragments containing tandem affinity purification (TAP) (1,13), floxed PGK/Hyg (14) and KanR. The gap-repair (GR) plasmid was constructed by inserting the MCI/TK gene (15) into pBlueScript (Stratagene). The sequence of these two plasmids and the plasmids themselves are available upon request.

Recombineering

The procedure for recombineering was essentially as described previously (5). E.coli DY380 harboring the EKLF BAC was grown at 30°C to an OD600 = 0.4–0.6 in Luria–Bertani Medium (LB) in the presence of 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The cells were then shifted to 42°C for 15 min to induce expression of λ recombination proteins Beta, Exo and Gam, followed by chilling in ice water for 10 min. Electrocompetent cells were prepared by washing the cells three times with 10% glycerol. Five hundred nanograms of PCR products were boiled for 1 min per 500 bp and then chilled in ice-cold water. The denatured DNA fragments were electroporated into 50 μl of ice-cold competent cells. After electroporation, 1 ml of LB medium was added to the cuvette, and the culture was incubated at 30°C for 3 h with shaking. The cells were then plated on selective media or pools of cells.

ES cell culture

V6.5 F1 hybrid ES cells (11) were maintained using standard methods (16).

Tetraploid blastocyst complementation

HA–EKLF–TAP mice were produced by tetraploid embryo complementation as described previously (10,11) with the following modifications. Briefly, B6D2F1 female mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were hormonally ovulated and bred to stud B6D2F1 males. During the following morning, fertilized eggs were collected in M2 media (MR-015-D, Specialty Media, Phillipsburg, NJ) and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2 in KSOM plus amino acids media (MR-106-D, Specialty Media) to two-cell embryos. Two-cell diploid embryos were fused individually to produce one-cell tetraploid embryos using a 100 μs, 100 V pulse from a CF-150/B electrofuser (Biological Laboratory Equipments, Hungary) with hand-held, insulated electrodes in M2 media. Ninety-nine percent of the two-cell embryos were converted to one-cell tetraploid embryos within 45 min by this simple procedure. Tetraploid embryos were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 50 h to blastocysts in KSOM plus amino acids media. Approximately 90% of tetraploid embryos produced blastocysts with an excellent blastocoele cavity. The ES cells were injected into tetraploid blastocysts with the aid of a Piezo Impact Drive Unit micromanipulator (PMM-150FU, Primetech, Ibaraki, Japan). Injected tetraploid blastocysts were transferred to the uterus of pseudopregnant CD1® female recipients (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Approximately 10% of tetraploid blastocysts that were injected with genetically modified ES cells yielded live-born pups. Forty percent of these pups survived to adulthood. Approximately 25% of tetraploid balstocysts that were injected with unmodified V6.5 ES cells yielded live-born pups and 50% of these pups survived to adulthood.

Primers

The sequences of all the primers used in this paper are listed below. Primers for TAPR plasmid construction: Bam-TAP-F, 5′-GGAGGATCCATGGAAAAGAGAAGATG-3′; Bam-TAP-R, 5′-ACTGGATCCTCAGGTTGACTTCCCCGC-3′. Primers for HA tagging: HA-KLF-5′, 5′-TAGCCCATGAGGCAGAAGAGAGAGAGGAGGCCTGAGGTCCAGGGTGGACACCAGCCAGCC-3′; KLF+79, 5′-AGTCCTCCTGGGTGTCCAGAA-3′. Primers for TAP tagging: KLF-L8-TAP-F2, 5′-tcgtcccttctgctgtggcctctgcccacgtgctttttcacgctctgaccacttagctctgcacatgaagcgtcacctcgcaggtgctggagccggtgcagggTCCATGGAAAAGAGAAGATG-3′; EKLF–TAP-R5, 5′-tataatggctcatcttttgggatacggtccttggatccactcttatttcatccccagtccttgtgcaggatcactcaTCGAATTCCTGCAGATAACTTC-3′. Primers for GR: pBSTK-GAP-F, 5′-ctctgtatagctttgactgtctgggaactcactctatagatcaggctggtTGACCATGATTACGCCAAGC-3′; pBSTK-GAP-R, 5′-cacagccattgagagaaactcacccaagaacttatgaggttcctgtggcaTCCGCTCACAATTCCACACAAC-3′. Primers for PCR screening: EKLF-F, 5′-GAGAGAAGCCTTATGCCTGC-3′; EKLF-R, 5′-TCTGGTGGTCTATATTGCTG-3′; KLF-188, 5′-AGACGCACACCACACACATA-3′; HA-R, 5′-AGTCGGGCACGTCGTAAG-3′; KLF+96, 5′-CCTCCCACACACTCACACT-3′; KLF-9F2, 5′-GCAGCAGCAGTAGTTTCATC-3′; TAP-R2, 5′-CGCCTGAGCATCATTTAG-3′; ES-R1, 5′-AGGGTCACCTAGTGCTTCCA-3′; Kan-F2, 5′-GCCTTCTTGACGAGTTCTT-3′.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The generation of knockin mice in 3 months is illustrated by tagging the endogenous murine EKLF gene with HA and TAP (1,13). EKLF is a C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor that is essential for the globin gene regulation (17–20). To study the cellular localization of EKLF during development and to define protein complexes containing EKLF in primary mouse tissues, we inserted an HA tag at the 5′ end and a TAP tag at the 3′ end of the endogenous mouse EKLF gene. In this paper, we report the method utilized to produce HA/EKLF/TAP knockin mice rapidly. The overall strategy is illustrated in Figure 1.

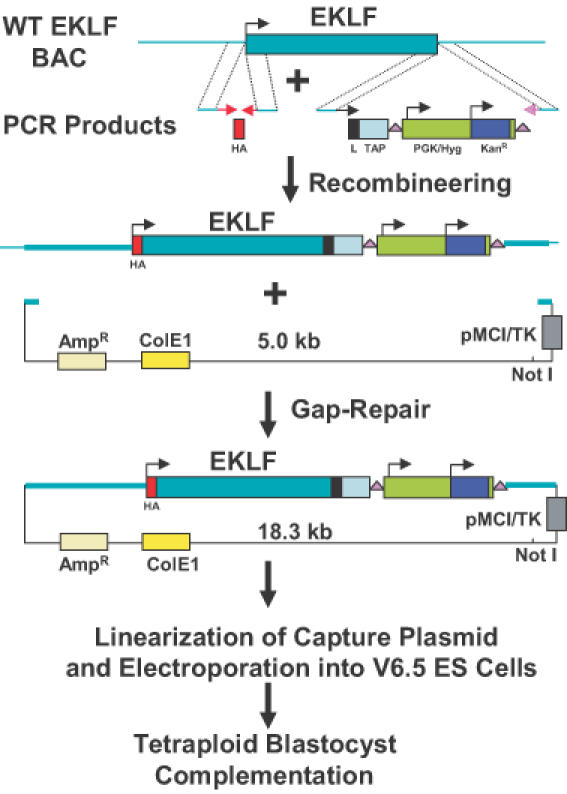

Figure 1.

Overview of method. A BAC clone containing the EKLF gene was transferred from the E.coli strain DH10B to the recombineering strain DY380. These cells were electroporated with PCR products containing an HA tag and a TAPR (Linker/TAP/loxP-PGK/Hyg/KanR-loxP) cassette flanked by 60–79 bp EKLF homologies. Cells containing the correctly modified BAC were electroporated with a PCR product containing AmpR, ColE1 and herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase sequences flanked by 50 bp homologies. By GR, this fragment rescued a 13.3 kb fragment containing the modified EKLF gene plus 6 kb of upstream sequence and 1 kb of downstream sequence. The resulting 18.3 kb plasmid was linearized with NotI and electroporated into the F1 hybrid (B6/129) ES cell line, V6.5. Hygromycin and gancylovir-resistant colonies were analyzed for homologous recombination by PCR and Southern blot hybridization. Correctly targeted ES cells were subsequently injected into tetraploid blastocysts to clone mice that are heterozygous for the tagged EKLF gene, HA–EKLF–TAP.

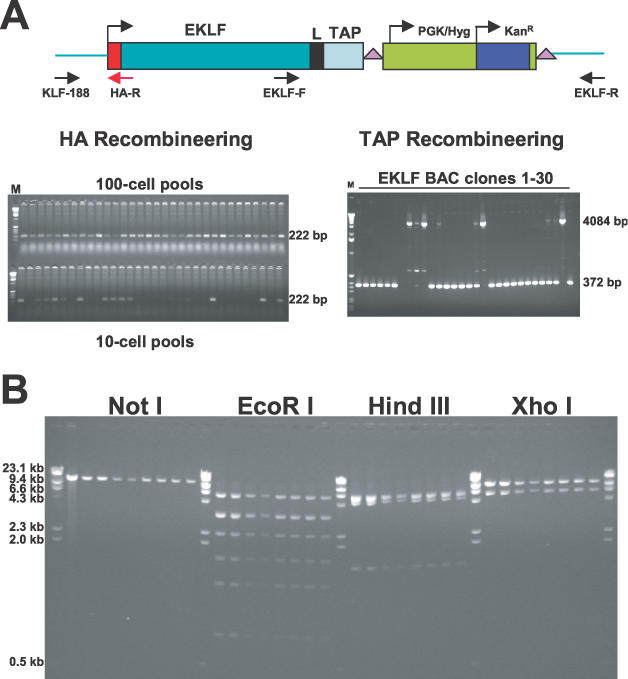

An EKLF BAC clone in DH10B was obtained from the BACPAC Resources Center at Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI). BAC DNA was purified and electroporated into E.coli DY380, which harbors the λ phage red system (5,6). To insert a TAP tag (with an 8 amino acid linker) into the 3′ end of the EKLF gene, two long oligonucleotides were used to amplify by PCR a TAPR (TAP Recombineering) plasmid containing the following cassette: linker/TAP/loxP-PGK/Hyg/KanR-loxP. The 5′ 79 or 77 bases of the two primers are homologous to sequences either immediately upstream or immediately downstream of the EKLF stop codon (TGA) (Figure 1) and the 3′ 20 or 22 bases are homologous to sequences at the ends of the TAPR cassette. The 3.9 kb PCR fragment was gel purified and electroporated into DY380/EKLF BAC after the induction of the λ recombination system by a 15 min incubation at 42°C. Thirty kanamycin-resistant colonies were obtained and PCR with primers EKLF-F and EKLF-R (Figure 2A) was used to identify homologous recombinants. As shown in Figure 2A, the 4084 bp band that was predicted for homologous recombinants was observed in four colonies. Twenty-one colonies contained only a 372 bp band and, therefore, were non-homologous recombinants. The remaining five clones were mixtures of homologous and non-homologous recombinants. Homologous recombinants were derived from these five clones when the original EKLF BAC was lost after further growth and isolation of single colonies. We then purified BAC DNA from the nine homologous recombinants and sequenced the TAP tag and the PGK/Hyg gene. Three of the nine BACs contained the correct sequences.

Figure 2.

HA- and TAP-tagging of the EKLF gene by homologous recombination in E. coli DY380. (A) Sib selection and kanamycin selection of HA- and TAP-tagged EKLF BACs. PCR fragments containing the HA tag or Linker/TAP/loxP-PGK/Hyg/KanR-loxP cassette were electroporated into E.coli DY380 containing the EKLF BAC clone. For the HA tag, pools of cells were prepared and screened by PCR with primers KLF-188 and HA-R. The predicted product for homologous recombinants is 222 bp. For the TAPR cassette, kanamycin- and chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were selected and homologous recombinants were confirmed by PCR with primers EKLF-F and EKLF-R. The predicted products for homologous recombinants is 4084 bp. A 372 bp product is predicted for the wild-type EKLF BAC. (B) Mapping of GR plasmids. To confirm the capture of HA–EKLF–TAP with appropriate flanking sequence, GR plasmids were digested with NotI, EcoRI, HindIII and XhoI, respectively. The number of fragments predicted for plasmids with correctly captured sequences are the following: NotI, 1 band (18.3 kb); EcoRI, 7 bands (5.7, 3.3, 3.2, 2.2, 1.8, 1.2 and 0.8 kb); HindIII, 4 bands (6.1, 5.7, 4.9 and 1.5 kb); XhoI, 2 bands (12.6 and 5.7 kb). In EcoRI digestion, the 3.3 and 3.2 kb bands move as a single band; whereas the 6.1 and 5.7 kb bands in HindIII digestion are inseparable in this gel.

An HA tag was inserted at the 5′ end of the EKLF gene in one of these clones by recombineering. Two methods were used to prepare an HA DNA fragment for electroporation into DY380 cells containing the TAP-tagged EKLF BAC clone. First, a 202 bp fragment containing HA–(11 amino acid linker)–EKLF sequences was derived by PCR amplification of an HA–linker–EKLF plasmid (21). This fragment contained an HA–linker sequence plus 60 bp of homology upstream and 79 bp of homology downstream of the EKLF ATG. Second, a 148 bp fragment containing the HA–linker sequence plus 50 bp of homology upstream and downstream of the EKLF ATG was derived by annealing two partially overlapping 98 base oligonucleotides (48 base overlap) and by extending these primers with T4 DNA polymerase. The fragments were gel-purified and electroporated into DY380 cells containing the TAP-tagged EKLF BAC clone. Correctly recombineered BACs were identified by sib selection. Pools of 100 cells and 10 cells were prepared by serial dilution, expanded by overnight growth and screened by PCR for homologous recombinants using an EKLF upstream primer (KLF-188) and a primer from within the HA tag (HA-R). Data for the first method of HA tagging are shown in Figure 2A. All the 100-cell pools and 13 of the 32 10-cell pools were positive for homologous recombinants. Four of the 10-cell pools were streaked on plates and individual colonies were examined by PCR. Four homologous recombinants were identified and sequencing confirmed that three of these clones contained the correct HA sequence. A similar efficiency of homologous recombination was observed using the second HA tagging method (data not shown).

The modified gene (HA–EKLF–TAP) with ∼6.0 kb of sequence upstream of HA and 1.0 kb of sequence downstream TAP was rescued from the HA–EKLF–TAP BAC clone by GR (Figure 1). The GR vector was a 5.0 kb DNA fragment generated by PCR amplification of a GR plasmid containing an ampicillin-resistance gene, a ColE1 replicon and a pMCI/TK gene (15). Two long primers were utilized for PCR. The 5′ 50 bases of the two primers were homologous to sequences either 6.0 kb upstream of HA or 1.0 kb downstream of TAP and the 3′ 20 or 22 bases were homologous to sequences at the ends of the linearized GR plasmid. The 5.0 kb PCR fragment was gel-purified and electroporated into induced DY380 containing the HA–EKLF–TAP BAC. Nine ampicillin/kanamycin-resistant colonies were picked and the DNA prepared from these colonies was digested with NotI, EcoRI, HindIII and XhoI. As shown in Figure 2B, the restriction patterns of all nine clones indicated that the 18.3 kb plasmid contained correctly captured HA–EKLF–TAP with the appropriate homology regions. Sequence analysis of the junctions between HA–EKLF–TAP and the GR plasmid vector in these clones confirmed that the predicted structure was produced (data not shown).

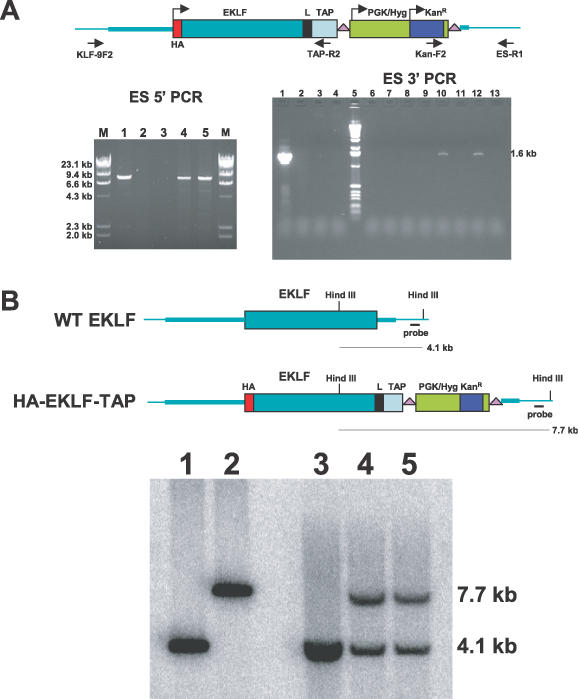

To replace the wild-type EKLF gene with HA–EKLF–TAP in ES cells, one of the capture plasmids was linearized by NotI digestion and electroporated into hybrid B6/129 F1 ES cell line V6.5 (11). After 8 days of selection in hygromycin and gancylovir, eight ES cell colonies were obtained. Genomic DNA from these colonies was analyzed by PCR with primers Kan-F2 and ES-R1. As shown in Figure 3A (ES 3′ PCR), colonies designated ES5 and ES7 (lanes 10 and 12) produced a 1.6 kb band that is predicted for homologous recombination. PCR amplification of HA–EKLF–TAP BAC DNA was used as a positive control (lane 1), and PCR amplifications of linearized capture plasmid (lane 2) and wild-type V6.5 ES cell DNA (lane 3) served as negative controls.

Figure 3.

Knockin of HA–EKLF–TAP in ES cells. (A) Mapping of the targeted ES cell locus by PCR. Genomic DNA was purified from ES cell clones and screened by PCR. For ES 5′ PCR, lane 1, modified EKLF BAC DNA; lane 2, wild-type V6.5 ES cells; lane 3, primer control; lanes 4 and 5, ES clones 5 and 7; lane M, molecular weight marker. For ES 3′ PCR, lane 1, modified EKLF BAC DNA; lane 2, linearized gap-repaired plasmid DNA; lane 3, wild-type V6.5 ES cells; lane 4, primer control; lane 5, 1.0 kb marker; lanes 6–13, ES cell clones 1–8. (B) Southern blot of targeted ES cell clones. Genomic DNA purified from ES cell clones was digested with HindIII and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. The probe was a 447 bp SnaBI fragment isolated from sequence downstream of the 1.0 kb homology. Lane 1, wild-type EKLF BAC; lane 2, modified EKLF BAC; lane 3, wild-type V6.5 ES cells; lanes 4 and 5, ES5 and ES7.

Correct targeting at the 5′ end was assessed by PCR amplification of genomic ES cell DNA using a TAP primer (TAP-R2) and a primer (KLF-9F2) derived from the sequence upstream of the 6 kb homology (Figure 3A, ES 5′ PCR). As expected, ES5 and ES7 (lanes 4 and 5) produced a 9.1 kb band which was identical to the one generated by the HA–EKLF–TAP BAC DNA control (lane 1). A 9.1 kb PCR fragment was not observed with wild-type V6.5 cell DNA (lane 2). Southern blot analysis of ES5 and ES7 DNA confirmed that one EKLF allele was replaced with HA–EKLF–TAP in these cells (Figure 3B). Lanes 4 (ES5) and 5 (ES7) of Figure 3B demonstrate that both ES cell clones contain the 4.1 kb wild-type allele and the 7.7 kb knockin allele. Control lanes 1 and 2 are the wild-type and knockin EKLF BAC DNA, respectively, and lane 3 is wild-type ES cell DNA.

Mice containing the HA–EKLF–TAP knockin allele were rapidly produced by the method of tetraploid embryo complementation. The production of mice by this method precludes the generation of chimeric mice that must be bred to demonstrate germline transmission. ES5 and ES7 cells were injected into tetraploid blastocysts and 121 of these blasts were transferred to the uteri of foster mothers. Twelve pups were born alive and five survived to adulthood. All were heterozygous for the HA–EKLF–TAP allele and no chimerism was observed. Each animal was derived entirely from the modified ES cells.

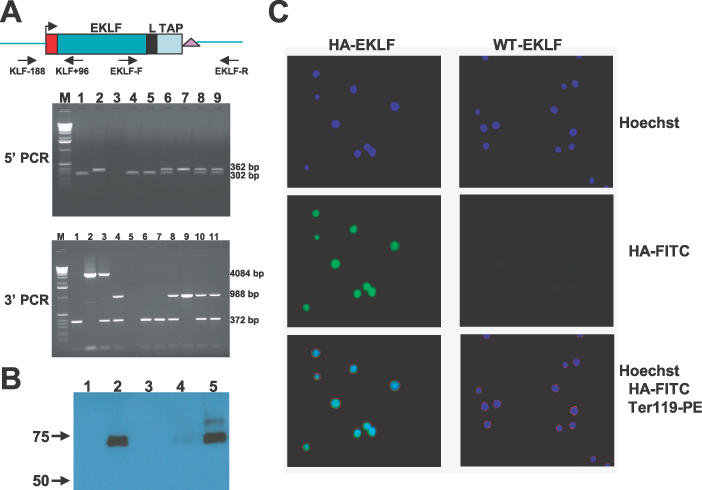

All the steps described above were completed in 3 months. To demonstrate that HA–EKLF–TAP is functional in vivo, we derived mice that were homozygous for the knockin. Heterozygous HA–EKLF–TAP males were bred to C57B6 females that express CRE recombinase from the cytomegalovirus promoter and the offspring were mated. Tail DNA from one litter of six pups was analyzed by PCR with 5′ primers KLF-188 and KLF+96, and the results are illustrated in Figure 4A (lanes 4–9). One of six pups was homozygous for HA–EKLF–TAP (lane 7). The six tail DNAs were also analyzed by PCR with 3′ primers EKLF-F and EKLF-R (lanes 6–11, Figure 4A). The segregation pattern was the same as observed above, and the same pup was homozygous for HA–EKLF–TAP (lane 9). Multiple litters were genotyped and, as expected, one-fourth of the pups were homozygous for HA–EKLF–TAP. Blood smears and hematological values (data not shown) were normal in these animals; therefore, HA–EKLF–TAP is functional in vivo.

Figure 4.

HA–EKLF–TAP expression in homozygous HA–EKLF–TAP mice. (A) PCR amplification of mouse tail DNA. For 5′ PCR, the predicted products for wild-type and HA–EKLF–TAP alleles are 302 and 362 bp, respectively. For 3′ PCR, the predicted products for wild-type and HA–EKLF–TAP alleles before CRE deletion are 372 and 4084 bp, respectively. After CRE deletion, the HA–EKLF–TAP allele is 988 bp. For 5′PCR, lane M, 1.0 kb marker; lane 1, wild-type C57B6 mouse; lane 2, modified EKLF BAC DNA; lane 3, primer control; lanes 4–9, individual pups in a single litter produced by mating heterozygotes. For 3′ PCR, lane M, 1.0 kb marker; lane 1, wild-type C57/B6 mouse; lane 2, modified EKLF BAC DNA; lane 3, a cloned heterozygous mouse; lane 4, a heterozygous mouse in which the PGK/Hyg/KanR markers have been removed by Cre recombinase; lane 5, primer control; lanes 6–11, same litter as above. (B) Western blot with anti-HA antibody. Whole-cell extracts were used in western blot. Lane 1, COS cells transfected with a control plasmid, pSG5; lane 2, COS cells transfected with an HA–EKLF–TAP cDNA plasmid, pDZ17; lane 3, Ter119+ bone marrow cells from a wild-type mouse; lane 4, Ter119− bone marrow cells from an HA–EKLF–TAP homozygous mouse; lane 5, Ter119+ bone marrow cells from an HA–EKLF–TAP homozygous mouse. (C) Fluorescent digital sections of Ter119+ bone marrow cells from a wild-type mouse and an HA–EKLF–TAP homozygous mouse stained with Hoechst, anti-HA monoclonal antibody conjugated with FITC and anti-Ter119 monoclonal antibody conjugated with PE.

Western Blot analysis of bone marrow cell extracts with an anti-HA monoclonal antibody confirmed HA–EKLF–TAP expression. Bone marrow cells from wild-type and HA–EKLF–TAP homozygous mice were separated into Ter119+ and Ter119− fractions on a MACS column (Miltenyi Biotech) using anti-Ter119 antibody linked to magnetic beads. Whole-cell protein extracts from these cells were analyzed. As shown in Figure 4B, two bands with molecular weights of ∼65 and 70 kDa were detected in the Ter119+ bone marrow cell fraction from HA–EKLF–TAP mice (lane 5) but not in Ter119+ cells from wild-type mice (lane 3). Low levels of the HA–EKLF–TAP doublet were also observed in the Ter119− fraction from HA–EKLF–TAP mice (lane 4). Similar bands were detected in a positive control sample derived from COS cells transfected with a HA–EKLF–TAP cDNA clone, pDZ17 (lane 2), but no protein was detected in whole-cell extracts prepared from COS cells transfected with a control vector pSG5 (lane 1). These results demonstrate that EKLF is expressed predominately in Ter119+ hematopoietic cells from the bone marrow.

The cellular localization of EKLF in bone marrow cells was tested by immunofluorescence microscopy. Bone marrow cells were prepared from wild-type and HA–EKLF–TAP homozygous mice and stained with PE-conjugated anti-Ter119 antibody. Ter119+ cells were then purified by FACS sorting, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal antibody. Figure 4C illustrates fluorescent, digital sections of these cells. The bottom left panel, which illustrates the merge of Hoechst, anti-Ter119-PE and anti-HA-FITC stains, demonstrates that HA–EKLF–TAP is localized in the nucleus in adult bone marrow erythroid cells.

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of recombineering and tetraploid blastocyst complementation (5,6,10,11) provides a method to produce knockin mice in 3 months. The novel plasmids described in this paper permit rapid TAP tagging of any gene in the murine genome. We anticipate that the use of this strategy will enable large-scale tagging of mouse genes and systematic identification of protein complexes during development.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Don Court for the E.coli recombineering strain DY380. We are grateful to Dr Rudolf Jaenisch for the V6.5 ES cells and members of the Townes laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NHLBI grants to T.M.R. and T.M.T., and a NIGMS grant to N.P.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gavin A.C., Bosche,M., Krause,R., Grandi,P., Marzioch,M., Bauer,A., Schultz,J., Rick,J.M., Michon,A.M., Cruciat,C.M. et al. (2002) Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature, 415, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho Y., Gruhler,A., Heilbut,A., Bader,G.D., Moore,L., Adams,S.L., Millar,A., Taylor,P., Bennett,K., Boutilier,K. et al. (2002) Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature, 415, 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee T.I., Rinaldi,N.J., Robert,F., Odom,D.T., Bar-Joseph,Z., Gerber,G.K., Hannett,N.M., Harbison,C.T., Thompson,C.M., Simon,I. et al. (2002) Transcriptional regulatory networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science, 298, 799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren B., Robert,F., Wyrick,J.J., Aparicio,O., Jennings,E.G., Simon,I., Zeitlinger,J., Schreiber,J., Hannett,N., Kanin,E. et al. (2000) Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science, 290, 2306–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee E.C., Yu,D., Martinez de Velasco,J., Tessarollo,L., Swing,D.A., Court,D.L., Jenkins,N.A. and Copeland,N.G. (2001) A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics, 73, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu D., Ellis,H.M., Lee,E.C., Jenkins,N.A., Copeland,N.G. and Court,D.L. (2000) An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5978–5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P., Jenkins,N.A. and Copeland,N.G. (2003) A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res., 13, 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotta-de-Almeida V., Schonhoff,S., Shibata,T., Leiter,A. and Snapper,S.B. (2003) A new method for rapidly generating gene-targeting vectors by engineering BACs through homologous recombination in bacteria. Genome Res., 13, 2190–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z.Q., Kiefer,F., Urbanek,P. and Wagner,E.F. (1997) Generation of completely embryonic stem cell-derived mutant mice using tetraploid blastocyst injection. Mech. Dev., 62, 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagy A., Rossant,J., Nagy,R., Abramow-Newerly,W. and Roder,J.C. (1993) Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 8424–8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggan K., Akutsu,H., Loring,J., Jackson-Grusby,L., Klemm,M., Rideout,W.M.,III, Yanagimachi,R. and Jaenisch,R. (2001) Hybrid vigor, fetal overgrowth, and viability of mice derived by nuclear cloning and tetraploid embryo complementation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 6209–6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maniatis T., Fritsch,E.F. and Sambrook,J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigaut G., Shevchenko,A., Rutz,B., Wilm,M., Mann,M. and Seraphin,B. (1999) A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol., 17, 1030–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauer B. and Henderson,N. (1989) Cre-stimulated recombination at loxP-containing DNA sequences placed into the mammalian genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 147–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansour S.L., Thomas,K.R. and Capecchi,M.R. (1988) Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cells: a general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature, 336, 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogan B., Beddington,R., Costantini,F. and Lacy,E. (1994) Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller I.J. and Bieker,J.J. (1993) A novel, erythroid cell-specific murine transcription factor that binds to the CACCC element and is related to the Kruppel family of nuclear proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 2776–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donze D., Townes,T.M. and Bieker,J.J. (1995) Role of erythroid Kruppel-like factor in human gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 1955–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuez B., Michalovich,D., Bygrave,A., Ploemacher,R. and Grosveld,F. (1995) Defective haematopoiesis in fetal liver resulting from inactivation of the EKLF gene. Nature, 375, 316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkins A.C., Sharpe,A.H. and Orkin,S.H. (1995) Lethal beta-thalassaemia in mice lacking the erythroid CACCC-transcription factor EKLF. Nature, 375, 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandya K., Donze,D. and Townes,T.M. (2001) Novel transactivation domain in erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF). J. Biol. Chem., 276, 8239–8243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]