Abstract

Mesenchymal cell types, under mesenchymal-epithelial interaction, are involved in tissue regeneration. Here we show that bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), subcutaneous preadipocytes, and dermal fibroblasts distinctively caused keratinocytes to promote epidermal regeneration, using a skin reconstruction model by their coculture with keratinocytes. Three mesenchymal cell types promoted the survival, growth, and differentiation of keratinocytes, whereas BMSCs and preadipocytes inhibited their apoptosis. BMSCs and preadipocytes induced keratinocytes to reorganize rete ridge- and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively. Keratinocytes with fibroblasts or BMSCs expressed the greatest amount of interleukin (IL)-1α protein, which is critical for mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in skin. Keratinocytes with or without three mesenchymal supports displayed another cross-talk molecule, c-Jun protein. Without direct mesenchymal-epithelial contact, the rete ridge- and epidermal ridge-like structures were not replicated, whereas the other phenomena noted above were. DNA microarray analysis showed that the mesenchymal-epithelial interaction affected various gene expressions of keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types. Our results suggest that not only skin-localized fibroblasts and preadipocytes but also BMSCs accelerate epidermal regeneration in complexes and that direct contact between keratinocytes and BMSCs or preadipocytes is required for the skin-specific morphogenesis above, through mechanisms that differ from the IL-1α/c-Jun pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal-epithelial interaction plays an essential role in organogenesis and tissue regeneration at both embryonic and adult stages (Saunders et al., 1957; Gilbert, 2003). In adult tissue regeneration, which contributes to the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and to its repair against injury by various agents, tissue-localized mesenchymal cell types actively participate under conditions of mesenchymal-epithelial cell communication (Rheinwald and Green, 1975; Demayo et al., 2002; Ootani et al., 2003). Recently, bone marrow mesenchymal cell types have also been shown to infiltrate into impaired tissues and to be involved in tissue regeneration and repair of certain organs (Petersen et al., 1999; Krause et al., 2001; Mitaka, 2001).

Wound healing is a promising model for studying the mechanisms of tissue regeneration of various organs. This healing process demonstrates dynamic regenerative processes consisting of inflammation, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and scarring (Cotran et al., 1999). In wound healing of the skin, epidermal regeneration is a critical event for reorganizing normal cutaneous structure (Tomlinson and Ferguson, 2003). Dermal fibroblasts play a crucial role in epidermal reepithelialization through their growth and cytokine and extracellular matrix production (Green and Thomas, 1978; el-Ghalbzouri et al., 2002). We have shown that a mesenchymal cell type of mature adipocytes in the subcutis promotes the reorganization of the epidermal layer together with keratinocyte growth and differentiation (Sugihara et al., 1991; Sugihara et al., 2001). However, whether subcutaneous adipose tissue-localized preadipocytes and BMSCs are able to effect epidermal regenerations remains to be elucidated. In addition, it is still obscure whether BMSCs, preadipocytes, and fibroblasts, with their mesenchymal cell type-specific characters, induce that different character to the epidermal regeneration of keratinocytes.

To clarify these important issues, we investigated the effects of BMSCs, subcutaneous preadipocytes, and dermal fibroblasts on epidermal regeneration of keratinocytes, using a cutaneous reconstruction model, in which three mesenchymal cell types were cocultured with keratinocytes under conditions with or without direct epithelial-mesenchymal contact. In the culture assemblies, characteristics of the epidermal structures together with keratinocyte growth, apoptosis, and differentiation were analyzed by histochemistry, morphometry, and immunohistochemistry. We also examined the expressions of IL-1α and c-Jun that are critical for mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in the skin (Maas-Szabowski et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2000; Szabowski et al., 2000; Angel et al., 2001; Li et al., 2003). To estimate the factors responsible for the epidermal regeneration under mesenchymal cell type-keratinocyte interactions, we also studied their gene expressions, using DNA microarray analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Keratinocytes and Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Types

All procedures involving animal materials were performed in accordance with the regulations laid down by the ethical guidelines of Saga University. Keratinocytes were isolated from newborn Wistar rats (Charles River Japan, Yokohama, Japan), as previously described (Sugihara et al., 2001). Briefly, skin was removed from the back and abdomen. Keratinocytes were obtained from the epidermis separated from the dermis. They were cultured and maintained in a complete medium of Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. For this study we used three mesenchymal cell types: 1) BMSCs, 2) preadipocytes of subcutaneous adipose tissue, and 3) dermal fibroblasts. BMSCs were isolated from the bone marrow of 4-wk-old Wistar rats (Charles River Japan) according to an established method (Wieczorek et al., 2003). Briefly, marrow was obtained by aspiration from the tibia with a 25-gauge needle. To obtain BMSCs, 1 × 106 marrow stromal cells were cultured in the complete medium. After overnight incubation, nonadherent cells were washed out with the medium, and only the adherent cells were then cultured in the same medium. One week later, these adherent cells were dissociated as BMSCs by trypsin treatment. We isolated preadipocytes from subcutaneous adipose tissue of 4-wk-old Wistar rats (Charles River Japan), as previously described (Manabe et al., 2003). Briefly, adipose tissue was minced and digested with collagenase solution for 20 min at 37°C, with gentle shaking. The cell suspension was filtered through a mesh (74-μm pore size) to remove undigested tissue. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was cultured in the complete medium as preadipocytes (Janke et al., 2002). We confirmed by immunohistochemistry described bellow that the BMSCs and preadipocytes did not express the hematopoietic lineage markers CD31, CD34, and CD45, and the endothelial cell marker von Willebrand factor (Zuk et al., 2002). Preadipocytes (> 95%) expressed S-100 protein (a marker of adipocytes and preadipocytes), and 1 μg/ml insulin stimulation induced cytoplasmic lipid droplets in these preadipocytes (> 90%). Thus, we considered that these isolated mesenchymal cell types had no contamination with hematopoietic and endothelial cell types. All cell types were cultured and maintained in the complete medium described above. A rat dermal fibroblast cell line (FR cells, American Tissue Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) was used as a representative of the dermal fibroblasts.

Reconstruction Model of Skin

To analyze the effects of the three mesenchymal cell types on the epidermal regeneration by keratinocytes, we reconstructed skin in vitro by coculture of keratinocytes with each of the mesenchymal cell types, as previously described (Sugihara et al., 2001). First, 2 ml of type I collagen gel solution (Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan) containing 2 × 106 of each of the mesenchymal cell types above was poured into a 30-mm-diameter dish with its bottom made of nitrocellulose membrane (Millicell-CM, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Second, 1 × 106 keratinocytes were overlaid on the mesenchymal cell–containing gel and cultured in the complete medium. Within 2–3 d the keratinocytes grew confluent, after which the prepared culture dish, referred to as the “inner” dish, was placed in a larger “outer” dish (90-mm diameter) containing 8 ml complete medium. Using this method, the keratinocytes were exposed to air, mimicking their environment in vivo. That is, keratinocytes were cultured on BMSC-, preadipocyte- and fibroblast-containing collagen gels. As a control, keratinocytes were cultured on a mesenchymal cell–free gel. Figure 1 (left side) illustrates these experimental conditions. In addition, to decide whether mesenchymal-epithelial interaction was mediated by a direct cell-cell contact, keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types were cocultured under a separate condition. To generate this condition, we put polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore) on a mesenchymal cell-containing gel and thereafter overlaid a 0.5 ml collagen gel on the membrane. Keratinocytes were then seeded on the gel, so that in this way the PVDF membrane did not allow direct contact between keratinocytes.

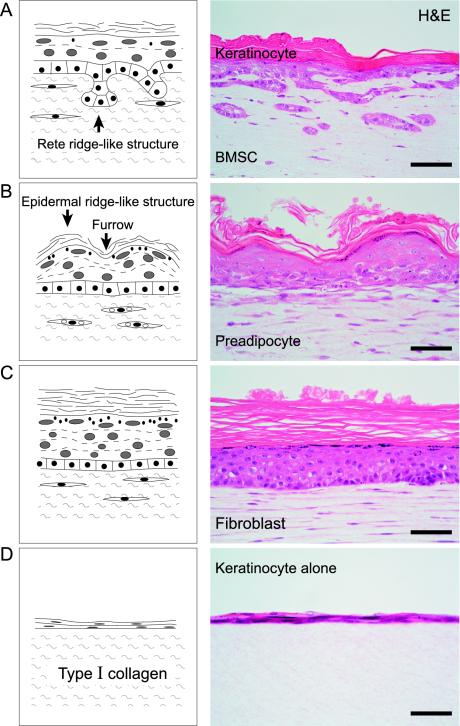

Figure 1.

Structures of regenerative epidermis caused by keratinocytes in a culture with (A–C) or without (D) mesenchymal-epithelial interaction. BM-SCs (A), preadipocytes (B), and fibroblasts (C) promote the stratification of keratinocytes and result in formation of epidermal layers made up of basal, prickle cell, granular and cornified layers, whereas keratinocytes alone (D) form only a thin epidermal layer. (A) BMSCs cause keratinocytes to reorganize the rete ridge-like structure. (B) Preadipocytes induce an epidermal ridge-like structure in the epidermal layer. (C) Fibroblasts induce the greatest thickness of granular and cornified layers in regenerative epidermis. Left side: schematic illustration; right side: H&E staining. Scale bar: 50 μm (A–D).

Structure and Morphometric Analysis

The culture assembly was fixed with 5% formalin, routinely processed, and then vertically embedded in paraffin. Deparaffinized sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In these stained sections we could easily identify the basal, prickle cell, granular and cornified layers. The thickness of these layers was measured by an objective micrometer in at least 10 randomly chosen noncontiguous and nonoverlapping fields of the sections at a high power view, 20× objective.

Immunohistochemistry

To characterize isolated BMSCs and preadipocytes, we examined the hematopoietic lineage markers CD31, CD34, and CD45, using their mouse monoclonal antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). We also examined the expression of the endothelial cell marker von Willebrand factor and the preadipocyte marker S-100 in the cell types, using their rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Dako). To examine the expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), which are suggested to be crucial for keratinocyte-mesenchymal interaction in the skin (Szabowski et al., 2000), mouse monoclonal IL-1α and c-Jun antibodies, and rabbit polyclonal KGF antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). To estimate the differentiating properties of keratinocytes, mouse monoclonal cytokeratin 10 (CK 10, a marker of suprabasal keratinocytes (Ivanyi et al., 1989) antibody (Dako) and cytokeratin 14 (CK 14, a marker of basal cells) antibodies (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) were used (Moll et al., 1982). To differentiate mesenchymal cell types from keratinocytes, mouse monoclonal vimentin antibody (Dako) was used. To characterize the direct or indirect mesenchymal-epithelial contact, we examined the expression of tenascin, which is crucial for organogenesis or morphogenesis (Lightner, 1994), using mouse mAb (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). To estimate myofibroblastic differentiation of mesenchymal cell types, we also examined the expression of α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin), using mouse mAb (Dako). To estimate the formation of basement membrane, we examined the expression of laminin and type IV collagen in culture assembly, using mouse monoclonal antibodies (Dako). Immunohistochemistry was carried out on deparaffinized sections by an avidin–biotin complex immunoperoxidase method, as described previously (Toda et al., 1999; Aoki et al., 2003). As a positive control, rat or human skin was used in an appropriate way for immunohistochemistry. As a negative control, phosphate-buffered saline or normal mouse and rabbit IgGs was used instead of each primary antibody. To avoid the possibility of nonspecific expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF, we carried out an absorption test as a negative control, using their blocking peptides (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). That is, IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF antibodies (1 μg) neutralized with IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF proteins, respectively (10 μg), were used. These results were always negative.

Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was examined by immunohistochemistry with mouse monoclonal proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody (Dako), as previously described (Wilkins et al., 1992). A total of 1000 cells were counted and the percentage of PCNA-positive nuclei was calculated. We also examined PCNA expression in newborn Wistar rat skin.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis was detected by immunohistochemistry with mouse monoclonal single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) antibody (Dako), as previously described (Suurmeijer et al., 1999). A total of 1000 cells were counted and the percentage of ssDNA-positive nuclei was calculated. We also examined ssDNA expression in newborn Wistar rat skin.

Microarray Analysis

To elucidate the gene expression of keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types during epidermal regeneration, we carried out DNA microarray analysis, using a mesenchymal cell type-keratinocyte separating condition that did not permit the contamination of the mesenchymal cell type- and keratinocyte-derived mRNAs. The materials were obtained from three independent experiments. The gene expression of keratinocytes with mesenchymal supports was compared with that of control keratinocytes, which were cultured on a mesenchymal cell–free collagen layer. The gene display of mesenchymal cell types with keratinocyte support were also compared with that of dermal FR fibroblasts alone. Broad-scale gene expression was performed by Atlas glass rat 1.0 microarrays (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA), which included 1081 rat DNA fragments; the complete list of the complementary sequences and controls is available on the Web site of the supplier (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/clontech/). Fluorescent labeling of mRNAs was performed using an Atlas glass fluorescent labeling kit (Clontech Laboratories) according to manufacturer's protocols. Synthesized first-stranded cDNAs from culture cell-derived mRNAs were labeled with fluorescence dyes, Cy3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan) at 25°C for 30 min. Hybridization of the microarray was carried out in a hybridization solution (supplied by Clontech Laboratories) for 16 h at 50°C. Washing of microarrays was performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. The microarrays were scanned in Cy3 channels with a microarray scanner, GenePix 4000B (Foster City, CA). QuantArray software (ArrayGauge) was used for image analysis. The average of the resulting total Cy3 signal gives a ratio that was used to balance or to normalize the signals. A ratio of more than twofold regulation was considered as a significant change in the gene expression.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Isogen reagent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of RNA (5 μg) were used in the reverse transcriptase (RT) reaction, using Random Hexamers as the primer, to generate first-strand cDNA and SuperScript reverse transcriptase (50 U/ml; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Frederick, MD), by following the manufacturer's instructions. The conditions for each PCR were determined in preliminary experiments and optimized for each set of primers. Expression levels of the IL-1α were determined with the following specific primers (5′ to 3′): CGCTTGAGTCGGCAAAGAAATC and CACATGCCATGCGAGTGA; primers for KGF (5′ to 3′): GTAGCGATCAACTCAAGGTC and ACAGCGATATCGAGACACTCA; and specific primers for the c-Jun (5′ to 3′): TGAGTGCAAGCGGTGTCTTA and TAGTGGTGATGTGCCCATTG. To amplify the GAPDH, the following primers (5′ to 3′) were used: TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA and AGATCCACAACGGATACATT. The amplification condition was one cycle at 94°C for 4 min. Then for IL-1α, 37 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (54°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min) with a final extension of 72°C for 7 min were used; the differences among the different amplifications were with regard to the number of cycles so that for c-Jun, there were 40 cycles, for KGF there were 36 cycles, and for GAPDH there were 34 cycles. The resulting PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2.0% (wt/vol) agarose gel in TBE (90 mM Tris/90 mM boric acid/2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and stained with ethidium bromide. The expected sizes for the PCR products were IL-1α(941 base pairs), KGF (570 base pairs), c-Jun (486 base pairs), and GAPDH (308 base pairs). The density of each band was quantified using NIH Image software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). We determined the relative gene expression by dividing the densitometric value of the mRNA RT-PCR product by that of the GAPDH product. The final ratio was obtained by dividing the value of treatment group by that of the control group.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained through five to seven independent experiments were analyzed by Scheffè test. Values represented the mean ± SD. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

BMSCs, Preadipocytes, and Fibroblasts Distinctively Promote Epidermal Regeneration

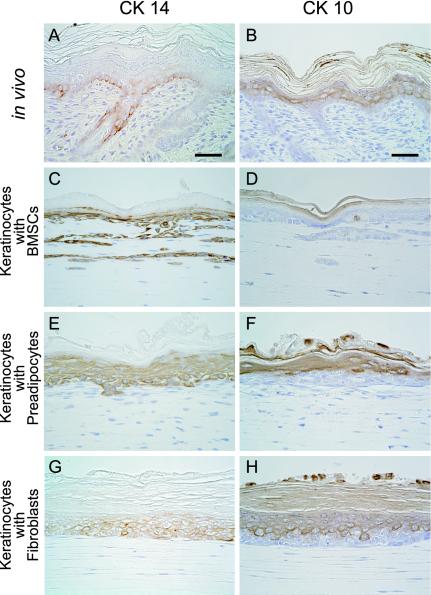

BMSCs, subcutaneous preadipocytes and dermal fibroblasts clearly promoted the stratification of keratinocytes, resulting in the formation of an epidermal layer consisting of basal, prickle cell, granular and cornified layers (Figure 1, A–C). In contrast, keratinocytes without these mesenchymal supports formed only a thin epidermal layer (Figure 1D) underwent apoptosis, and disappeared in the culture assembly after 14 d. Dermal fibroblasts, among the mesenchymal cell types, caused keratinocytes to reorganize the greatest thickness of prickle cell, granular and cornified layers (Figure 1C). Only BMSCs made it possible for keratinocytes to reconstruct a rete ridge-like structure in a basal layer (Figure 1A), whereas preadipocytes and fibroblasts could not. Preadipocytes induced an epidermal ridge-like structure in the regenerative epidermis (Figure 1B), whereas the others did not. CK 14, which displayed locally in basal layer of the skin in vivo (Figure 2A), was expressed in the basal to granular layer of the epidermis reorganized by keratinocytes with mesenchymal support (Figure 2, C, E, and G). This suggests that the cytoskeletal maturity of keratinocytes in regenerative epidermis may require other factors in addition to mesenchymal-epithelial interaction. CK 10 (a marker of suprabasal keratinocytes) expression pattern of keratinocytes with mesenchymal support was similar to that of keratinocytes in vivo (Figure 2, B, D, F, and H). In addition, the expression of basement membrane proteins, laminin and type IV collagen, was not affected by three mesenchymal cell types. This suggests that basement membrane formation by keratinocytes may not require mesenchymal support. Finally, in all of the conditions, three mesenchymal cell types did not express the hematopoietic lineage markers CD31, CD34, and CD45, and the endothelial cell marker von Willebrand factor. These cells did not undergo angiogenesis in a collagen gel.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression of cytokeratin 14 (CK 14) and cytokeratin 10 (CK 10) in normal rat skin (A and B) and regenerative epidermis by keratinocytes with mesenchymal support (C–H). In normal rat skin (A), only basal cells express CK 14. However CK 14 is expressed in the basal to granular layer of epidermis regenerated by keratinocytes with BMSC (C), preadipocyte (E), or fibroblast (G) support. CK 10 is expressed in the suprabasal layer of the epidermis reorganized by keratinocytes with BMSC (D), preadipocyte (F), or fibroblast (H) support, as well as normal skin (B). No mesenchymal cell types display CK14 and CK 10. Scale bar: 50 μm (A–H).

Mesenchymal Cell Types Promote Keratinocyte Growth

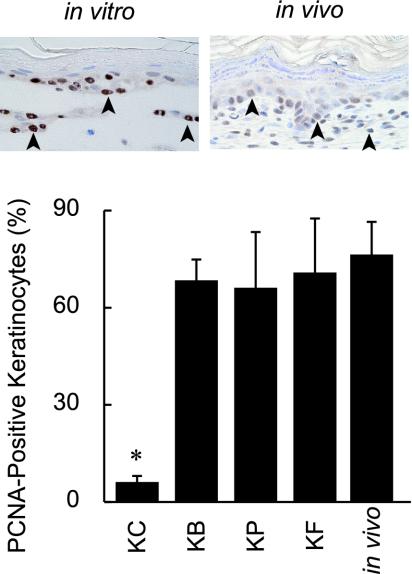

Effects of BMSCs, preadipocytes and fibroblasts on keratinocyte proliferation were examined by immunohistochemistry for PCNA at 7 d in culture. PCNA-positive cells (insets of Figure 3) were limited within the basal layer in all conditions. The PCNA-labeling index of keratinocytes with each of three mesenchymal cell types was higher in a cell type–independent manner than that of keratinocytes without mesenchymal support (Figure 3). The index of keratinocytes with mesenchymal support in vitro was similar to that of keratinocytes in vivo (Figure 3). There were no differences in the indices of each of the mesenchymal cell types among the all conditions.

Figure 3.

Detection of keratinocyte growth by immunohistochemistry with PCNA in vitro and in vivo. The insets show PCNA-positive nuclei (arrowheads) within a basal layer of epidermis in vivo (left) and in vitro with BMSC support (right). Percentages of PCNA-positive cells in epidermis regenerated by keratinocytes with BMSC, preadipocyte, and fibroblast supports are 68.3 ± 7.8, 66.0 ± 17.2, and 70.7 ± 17.0 (%), respectively. There are no significant differences among these values. The percentage of keratinocytes alone is significantly lower than that of keratinocytes with each of BMSC, preadipocyte, and fibroblast supports (*p < 0.001). Percentage of PCNA-positive keratinocytes is 77.2 ± 7.8 (%) in normal skin of the newborn Wistar rat.

BMSCs and Preadipocytes Inhibit Keratinocyte Apoptosis

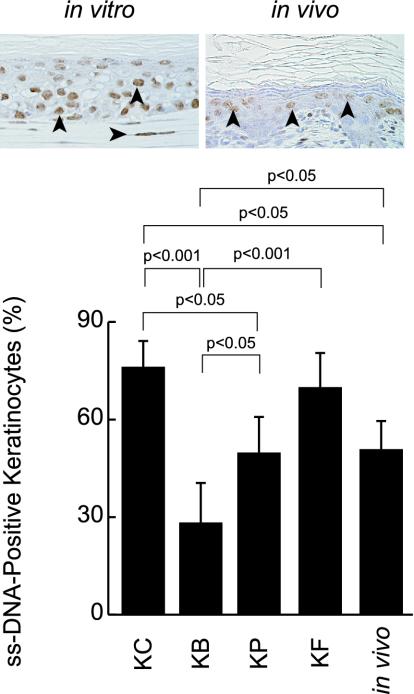

Effects of BMSCs, preadipocytes and fibroblasts on keratinocyte apoptosis were determined by immunohistochemistry for ssDNA antibody at 7 d of culture (insets of Figure 4). The ssDNA-labeling index of keratinocytes with BMSCs was significantly the lowest, followed in order by that of keratinocytes with preadipocytes and then fibroblasts (Figure 4). The index of keratinocytes without any mesenchymal support was similar to that of keratinocytes with fibroblasts (Figure 4). These results suggest that the cellular turnover rate of keratinocytes with fibroblasts is higher than that of keratinocytes with BMSCs or preadipocytes, because there was no difference in growth of keratinocytes with each of three mesenchymal cell types. The index of keratinocytes in vivo was similar to that of keratinocytes with preadipocytes or fibroblasts (Figure 4). There were no differences in the ssDNA-positive rates of the mesenchymal cell types under mesenchymal-epithelial interaction.

Figure 4.

Detection of apoptosis of keratinocytes by immunohistochemistry for ssDNA antibody in vitro and in vivo. The insets show ssDNA-positive keratinocytes in vivo (left) and in vitro with preadipocyte support (left). Percentages of ssDNA-positive keratinocytes with BMSCs, preadipocytes and fibroblasts are 28.2 ± 10.5, 49.7 ± 10.0 and 69.8 ± 13.6 (%), respectively. The percentage of keratinocytes alone is 76.1 ± 10.0. There are significant differences among these values, as indicated in the figure, although there is no significance difference between the values of keratinocytes alone and keratinocytes with fibroblasts. The percentage of keratinocytes in normal skin of the newborn Wistar rat is 51.0 ± 9.7 (%).

Immunohistochemical Expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF in Mesenchymal-Epithelial Interaction

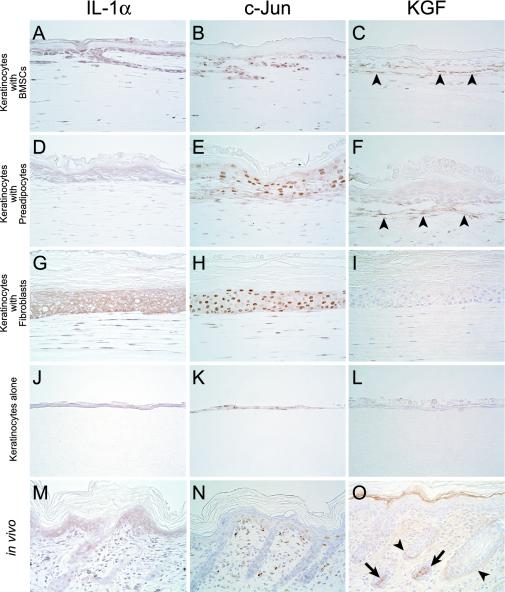

In this study, we investigated the expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF proteins, which are all critical for mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in the skin (Ng et al., 2000; Szabowski et al., 2000; Angel et al., 2001; Li et al., 2003). BMSCs and fibroblasts promoted a higher level of expression of IL-1α in keratinocytes than preadipocytes or keratinocytes alone. Fibroblasts had the highest IL-1α expression of mesenchymal cell types, followed in order by BMSCs and preadipocytes. IL-1α expression of keratinocytes in vivo was similar to that of keratinocytes with preadipocytes or of keratinocytes alone. Both fibroblasts in vivo and in vitro displayed IL-1α similarly (Figure 5, A, D, G, J, and M). c-Jun expression of keratinocytes with mesenchymal support was higher than that of keratinocytes alone. Fibroblasts had the greatest display of c-Jun, followed in order by BMSCs and preadipocytes. c-Jun expression of keratinocytes in vivo was similar to that of keratinocytes alone in vitro. Both fibroblasts in vivo and in vitro expressed c-Jun similarly (Figure 5, B, E, H, K, and N). Keratinocytes expressed IL-1α and c-Jun more prominently than the three mesenchymal cell types. KGF was not detected in any keratinocytes with or without mesenchymal support, whereas both BMSCs and preadipocytes located near the regenerative epidermis expressed KGF. In vivo, KGF was detected in hair bulb and external root sheath of hair follicles, and dermal stroma, although its nonspecific expression was observed in cornified layer (Figure 5, C, F, I, L, and O), supporting previous results (Werner, 1998).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF in vitro and in vivo. Keratinocytes alone (J) as well as the cells with preadipocytes (D) express IL-1α weakly. Keratinocytes with BMSCs (A) as well as the cells with fibroblasts (G) strongly display IL-1α. In IL-1α expression of mesenchymal cell types, though weakly, fibroblasts (G) show the highest, followed in order by BMSCs (A) and preadipocytes (D). Keratinocytes among all conditions express IL-1α more prominently than the three mesenchymal cell types. IL-1α expression of keratinocytes in vivo (M) was similar to that of keratinocytes with preadipocytes (D) or of keratinocytes alone (J). Both fibroblasts in vivo (M) and in vitro (G) displayed IL-1α similarly. c-Jun expression of keratinocytes with mesenchymal support (B, E, and H) was higher than that of keratinocytes alone (K). In mesenchymal cell types, c-Jun expressions of fibroblasts (H) were the greatest, followed in order by BMSCs (B) and preadipocytes (E). Keratinocytes express c-Jun more prominently among all conditions than the three mesenchymal cell types. c-Jun expression of keratinocytes in vivo (N) was similar to that of keratinocytes alone in vitro (K). Both fibroblasts in vivo (N) and in vitro (H) expressed c-Jun similarly. Only BMSCs (C) and preadipocytes (F) located near the regenerative epidermis express KGF, whereas it is not detected in any keratinocytes with (C, F, and I) or without mesenchymal support (L) and fibroblasts (I). In vivo, KGF (O) was detected in hair bulb (arrows) and external root sheath (arrowheads) of hair follicles, and dermal stroma, although its nonspecific expression was observed in cornified layer. Scale bar: 50 μm (A–L).

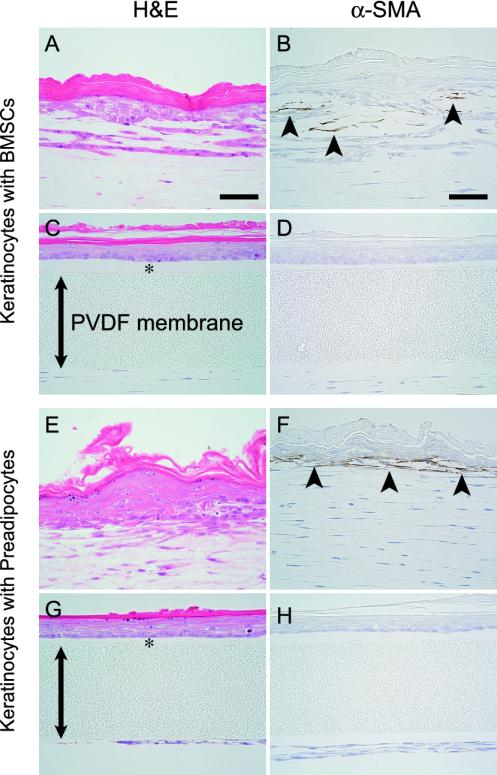

Effects of Indirect Contact Between Mesenchymal Cell Types and Keratinocytes on Epidermal Morphogenesis

To determine whether mesenchymal-epithelial interaction is mediated by a direct cell-cell contact, keratinocytes and each of the mesenchymal cell types were cocultured under conditions that did not allow their direct contact. In these conditions, BMSCs and preadipocytes did not induce keratinocytes to organize rete ridge-like and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively (Figure 6, A, C, E, and G). However, the other phenomena described above were clearly replicated even under conditions of indirect contact between keratinocytes and the mesenchymal cell types. These results indicate that direct contact between keratinocytes and BM-SCs or preadipocytes are required for the morphogenesis of rete ridge-like and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively. In addition, we did not detect tenascin in any epidermal cells, mesenchymal cell types and stroma under direct or indirect epithelial-mesenchymal contact. Interestingly, BMSCs and preadipocytes located near the epidermal layer, expressed α-SMA under direct mesenchymal-epithelial contact, although BMSCs and preadipocytes that were distantly located from the epidermal layer did not express α-SMA (Figure 6, B and F). BMSCs and preadipocytes did not express α-SMA under indirect mesenchymal-epithelial contact (Figure 6, D and H). Some fibroblasts can express α-SMA sporadically under both direct and indirect mesenchymal-epithelial contact.

Figure 6.

Structures of epidermis and immunohistochemical expression of α-SMA in coculture of keratinocytes with BMSCs (A–D) and preadipocytes (E–H) under conditions with (A, B, E, and F) or without direct epithelial-mesenchymal contact (C, D, G and H); the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (double arrow) does not allow keratinocytes and each of the mesenchymal cell types to directly come into contact with each other. Basal layers reorganized by keratinocytes with BMSCs (C) and preadipocytes (G) under their indirect adhesion remain as linear structures, whereas keratinocytes with BMSCs (A) and preadipocytes (E) under their direct adhesion organize rete ridge-like and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively. BMSCs (B) and preadipocytes (F) that are located near epidermal layer express α-SMA under direct mesenchymal-epithelial adhesion, although BMSCs (B) and preadipocytes (F) that are located distant from the epidermal layer do not express α-SMA. BMSCs (D) and preadipocytes (H) do not display α-SMA under indirect mesenchymal-epithelial adhesion. H&E staining (A, C, E and G) and immunohistochemistry for α-SMA (B, D, F, and H). (*) collagen gel layer. Scale bar: 50 μm (A–H).

Gene Expression by Microarray Analysis under Mesenchymal-Epithelial Interaction

We studied the gene expression of keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types with or without mesenchymal-epithelial interaction under mesenchymal cell type-keratinocyte separating conditions, using DNA microarray analysis. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the expression of the various genes that are suggested to be critical for mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in the skin. Asterisks in Table 1 show the ratios of more than twofold decreased regulation of the following genes, compared with keratinocyte control: IL-1α in keratinocytes with preadipocytes, IL-1β in keratinocytes with preadipocytes and fibroblasts, JunB in keratinocytes with fibroblasts, and KGF in keratinocytes with preadipocytes. Asterisks of Table 2 indicate the ratios of more than twofold increased regulation of the following genes, compared with fibroblast control: IL-1α and IL-1β in BMSCs with keratinocytes, KGF in BMSCs, and preadipocytes and fibroblasts with keratinocytes. Tables 3 and 4 summarize the levels of expression of the various genes in keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types, respectively, with or without mesenchymal-epithelial interaction.

Table 1.

Cutaneous mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk gene expression of keratinocytes with or without mesenchymal support

| Gene | GenBank no. | Keratinocyte control | With BMSCs | With preadipocytes | With fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | D00403 | 1.00 | 0.62 | *0.32 | 0.64 |

| IL-1β | M98820 | 1.00 | 0.54 | *0.25 | 0.57 |

| c-Jun | X17163 | 1.00 | 1.21 | 0.91 | 0.53 |

| JunB | X54686 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.86 | *0.46 |

| KGF | X56551 | 1.00 | 0.94 | *0.16 | 0.53 |

| GM-CSF | U00620 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.51 |

Values represent original ratios compared to the control keratinocyte gene expression as 1. Asterisks indicate ratios of more than twofold regulation.

Table 2.

Cutaneous mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk gene expression of mesenchymal cell types with or without keratinocyte support

| Gene | GenBank no. | Fibroblast control | BMSCs | Preadipocytes | Fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | D00403 | 1.00 | *2.69 | 1.18 | 1.16 |

| IL-1β | M98820 | 1.00 | *2.17 | 1.19 | 1.35 |

| c-Jun | X17163 | 1.00 | 1.49 | 0.75 | 1.07 |

| JunB | X54686 | 1.00 | 1.28 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| KGF | X56551 | 1.00 | *4.21 | *2.18 | *2.00 |

| GM-CSF | U00620 | 1.00 | 1.81 | 1.11 | 1.47 |

Values represent original ratios compared to the control fibroblast gene expression as 1. Asterisks indicate ratios of more than twofold regulation.

Table 3.

Significantly regulated genes in keratinocytes with or without mesenchymal support

| Gene | GenBank no. | Keratinocyte control | With BMSCs | With preadipocytes | With fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bax-alpha | U49729 | 1.00 | 5.47 | 7.03 | 3.11 |

| bcl-2 | L14680 | 1.00 | 11.46 | 74.23 | 4.75 |

| c-fms | X61479 | 1.00 | 2.41 | 9.68 | 2.03 |

| GIRK4 | L35771 | 1.00 | 7.49 | 19.01 | 20.07 |

| Kv3.2 | M84203 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.35 |

| PRKAR1A | M17086 | 1.00 | 2.19 | 4.42 | 3.38 |

| SHPS-1 | D85183 | 1.00 | 24.62 | 15.69 | 10.84 |

| Somatostatin | M25890 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 2.92 | 0.24 |

| TXR2 | D21158 | 1.00 | 3.32 | 3.03 | 2.76 |

| VSNL2 | D13125 | 1.00 | 2.85 | 3.39 | 8.03 |

Values represent original ratios compared to the control keratinocyte gene expression as 1. Abbreviations: 1) Bax-alpha, Bcl-2-associated X protein membrane isoform alpha; 2) bcl-2, B-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 2; 3) c-fms, macrophage colony-stimulating factor I receptor; 4) GIRK4, G protein-activated inward rectifier potassium channel 4; 5) Kv3.2, voltage-gated potassium channel protein 3.2; 6) PRKARIA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase type I alpha regulatory subunit; 7) SHPS-1, receptor-like protein with SH2 binding site; 8) TXR 2, thromboxane A2 receptor; and 9) VSNL2, neural visinin-like protein 2.

Table 4.

Significantly regulated genes in mesenchymal cell types with or without keratinocyte support

| Gene | GenBank no. | Fibroblast control | BMSCs | Preadipocytes | Fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11DH | J05107 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.41 |

| beta-ARK1 | M87854 | 1.00 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.33 |

| Ehk3 | U21954 | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| IGFBP5 | M62781 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Pep T2 | D63149 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.45 |

| PYY | M17523 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| RET1 | U97142 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| SHPS-1 | D85183 | 1.00 | 11.76 | 12.17 | 0.35 |

| VAMP-2 | M24105 | 1.00 | 3.71 | 8.84 | 2.84 |

Values represent original ratios compared to the control fibroblast gene expression as 1. Abbreviation: 1) 11-DH, corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 1; 2) beta-ARK1, beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1; 3) Ehk 3, ephrin type-A receptor 7; 4) IGFBP5, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5; 5) Pep T2, kidney oligopeptide transporter; peptide transporter 2; 6) RET1, RET ligand 1; 7) PYY, peptide YY; 8) VAMP 2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2.

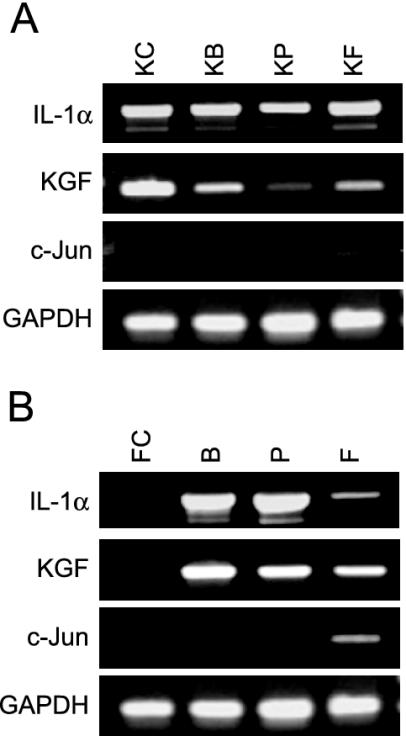

Gene Expression of IL-1α, KGF, and c-Jun by Semiquantitative RT-PCR Analysis

We carried out semiquantitative RT-PCR to estimate the validity of microarray-based gene expression of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF, which are all critical for keratinocyte-fibroblast interaction in the skin. IL-1α and KGF were detected in keratinocytes in all conditions, and keratinocytes with preadipocytes tended to show the lowest level of these genes (Figure 7A). IL-1 α and KGF were expressed in the mesenchymal cell types only under mesenchymal cell-keratinocyte interaction, and their expression tended to be lowest in fibroblasts with keratinocytes (Figure 7B). c-Jun was weakly detected in both keratinocytes and fibroblasts only under keratinocyte-fibroblast interaction (Figure 7, A and B). These results suggest that there is a discrepancy between microarray- and semiquantitative RT-PCR–based expressions of IL-1α in mesenchymal cell types, and of c-Jun in both keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types.

Figure 7.

IL-1α, KGF, and c-Jun mRNA expression of keratinocytes (A) and mesenchymal cell types (B) by RT-PCR. IL-1α and KGF of keratinocytes are detected in all conditions, and keratinocytes with preadipocytes (KP) tend to show the lowest level of these genes. IL-1 α and KGF are expressed only in the mesenchymal cell types under mesenchymal cell-keratinocyte interaction, and their expressions in fibroblasts with keratinocytes (F) tend to be lowest. c-Jun is detected in both keratinocytes (KF) and fibroblasts (F) only under keratinocyte-fibroblast interaction. KC, keratinocytes alone; KB, keratinocytes with BMSCs; KP, keratinocytes with preadipocytes; KF, keratinocytes with fibroblasts; FC, fibroblasts alone; B, BMSCs with keratinocytes; P, preadipocytes with keratinocytes; and F, fibroblasts with keratinocytes.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that BMSCs, subcutaneous preadipocytes and dermal fibroblasts promote epidermal regeneration in a skin reconstruction model. In contrast, keratinocytes without mesenchymal support undergo apoptosis and disappear in a culture assembly after 14 d. This suggests that mesenchymal support is critical for the survival, growth, and differentiation of keratinocytes (Rheinwald and Green, 1975; Green et al., 1977). Fibroblasts and mature adipocytes induced keratinocytes to form epidermal stratified structures (Sugihara et al., 2001), whereas only BMSCs and preadipocytes caused them to organize the rete ridge- and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively. This suggests that BMSCs and preadipocytes may play a more vital role than fibroblasts and mature adipocytes in epidermal integration during wound healing. In addition, we have not shown the effects of mixed subpopulations of mesenchymal cell types on epidermal regeneration. To estimate the mechanisms involved in the regeneration, forthcoming studies with different subpopulations of adipose tissue and bone marrow would be helpful.

In this study, keratinocytes with BMSCs, preadipocytes and fibroblasts as well as keratinocytes in vivo expressed CK 10 in suprabasal layer, but not in basal layer. However, CK 14 was displayed in both basal and suprabasal keratinocytes of regenerative epidermis with mesenchymal support, whereas it is expressed only in basal cells in vivo. This suggests that suprabasal keratinocytes in reconstructed epidermis may retain an immature property of basal cells. To further examine the differentiating properties of the epidermal layer, we preliminarily tried to detect cytokeratins 5/8 and 19, and involucrin. But we did not detect these molecules in both reconstructed epidermis and natural skin. To address this issue, further studies are needed.

In our study, the growth, apoptosis, and IL-1α/c-Jun pathway of keratinocytes showed no change under conditions with or without direct contact between keratinocytes and each mesenchymal cell types. This suggests that autocrine and paracrine pathways regulate these events during epidermal regeneration in a direct cell-cell contact-independent manner. In contrast, BMSCs and preadipocytes cause keratinocytes to organize the rete ridge- and epidermal ridge-like structures, respectively. However, this only occurred in conditions with direct cell-cell contact, whereas fibroblasts failed to induce these structures. It seems likely that BMSCs and preadipocytes integrate these skin-specific structures through their direct cell-cell contact-dependent mechanisms, which are different from IL-1α/c-Jun pathway. In addition, BMSCs and preadipocytes which were located near the epidermal layer expressed α-SMA, suggesting that they regain myofibroblastic differentiation only under their direct contact with keratinocytes. The myofibroblastic differentiation of BM-SCs and preadipocytes may contribute to wound contraction. Finally, to estimate the transdifferentiation of mesenchymal cell types into keratinocytes, we carried out the following preliminary study, using a PKH 2 fluorescent staining kit (Zynaxis Cell Science, Malvern, PA), as previously described (Toda et al., 1993). When PHK 2 dyelabeled mesenchymal cell types and -nonlabeled keratinocytes were cocultured, we did not detect the dye-labeled cells in the regenerative epidermis. It seems unlikely that mesenchymal cell types may transdifferentiate into keratinocytes. However, the issue is crucial, and thus we will study this process, using in vitro and in vivo systems.

Mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in skin is controlled by various molecules, including IL-1α, IL-1β, c-Jun, JunB, and KGF (Maas-Szabowski et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2000; Szabowski et al., 2000; Angel et al., 2001; Li et al., 2003). In this study, fibroblasts and BMSCs promote IL-1α protein expression of keratinocytes more prominently than preadipocytes. Fibroblasts show the highest c-Jun protein expression in mesenchymal cell types with keratinocyte support, followed in order by BMSCs and preadipocytes. This suggests that fibroblasts, BMSCs, and preadipocytes, in that order, may be involved in the mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in skin. In our study, KGF protein was expressed in BMSCs and preadipocytes only under their direct contact with keratinocytes, suggesting that BMSCs and preadipocytes may be involved in KGF production during epidermal regeneration. Furthermore, the degree of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF protein expression in keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types with or without their interaction was not parallel to that of these mRNA expressions by microarray and RT-PCR analyses. We have not clarified the reasons for this discrepancy, and it is conceivable that the pathway of IL-1α, c-Jun, and KGF protein production from their mRNA expression may be complexly regulated by unknown factors. This idea is support by recent evidence that the discrepancy between proteome and transcriptional regulation, apart from different translation efficiency, indicates a changed turnover rate of proteins in different conditions (Ohlmeier et al., 2004).

In this study, there was a discrepancy between microarray- and RT-PCR–derived data in keratinocytes and mesenchymal cell types. In microarray the housekeeping genes GAPDH, cytoplasmic beta actin and 40S ribosomal protein S29 were used as a control, whereas only GAPDH was used in RT-PCR. Therefore, different selection of the housekeeping genes may be responsible for the discrepancy above. It is also conceivable that the discrepancy may depend on the labeling efficiency of cDNAs with fluorescence dyes in microarray. Although the precise reason remains unclear, our results support the recent facts that there may be a discrepancy among the data of gene expressions by DNA microarray, RT-PCR, etc. (Eriksson et al., 2003). Thus, we think that one should estimate the validity of the microarray-based gene expressions in our study.

BMSCs and preadipocytes may not be the major cell types of normal skin. However, as we described, BMSCs and preadipocytes promote epidermal regeneration. Recent studies (Kawamoto et al., 2002; Sata et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003; Korbling and Estrov, 2003) have shown 1) that marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells exist in adult circulation and 2) that the progenitor cells differentiate into endothelial cells after homing to neovascularization sites. Preadipocytes develop from mature adipocytes under adipocyte-endothelial cell interaction (Aoki et al., 2003). Taken together, these results suggest that homing BMSCs and preadipocytes may contribute to epidermal regeneration in wound healing and to homeostasis of skin structure.

In conclusion, we have shown that not only skin-localized fibroblasts and preadipocytes, but also BMSCs promote epidermal regeneration. We have also shown that direct contact between keratinocytes and BMSCs or preadipocytes is required for the skin-specific morphogenesis. This suggests that BMSCs and preadipocytes may be applicable to cellular therapy for skin injuries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Hirase for helpful discussions regarding this work; H. Ideguchi, F. Mutoh, S. Nakahara, M. Nishida and N. Isakari for technical assistance; and A. Fushihara for typing the manuscript.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04–01–0038. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04–01–0038.

Abbreviations used: α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; AP-1, activator protein 1; BMSC, bone marrow stromal cell; CK, cytokeratin; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IL, interleukin; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

References

- Angel, P., Szabowski, A., and Schorpp-Kistner, M. (2001). Function and regulation of AP-1 subunits in skin physiology and pathology. Oncogene 20, 2413-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, S., Toda, S., Sakemi, T., and Sugihara, H. (2003). Coculture of endothelial cells and mature adipocytes actively promotes immature preadipocyte development in vitro. Cell Struct. Funct. 28, 55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotran, R., Kumar, V., and Collins, T. (1999). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Demayo, F., Minoo, P., Plopper, C.G., Schuger, L., Shannon, J., and Torday, J.S. (2002). Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in lung development and repair: are modeling and remodeling the same process? Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 283, L510-L517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Ghalbzouri, A., Gibbs, S., Lamme, E., Van Blitterswijk, C.A., and Ponec, M. (2002). Effect of fibroblasts on epidermal regeneration. Br. J. Dermatol. 147, 230-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, E., Forsgren, A., and Riesbeck, K. (2003). Several gene programs are induced in ciprofloxacin-treated human lymphocytes as revealed by microarray analysis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74, 456-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, S.F. (2003). Developmental Biology, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Green, H., Rheinwald, J.G., and Sun, T.T. (1977). Properties of an epithelial cell type in culture: the epidermal keratinocyte and its dependence on products of the fibroblast. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 17, 493-500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, H., and Thomas, J. (1978). Pattern formation by cultured human epidermal cells: development of curved ridges resembling dermatoglyphs. Science 200, 1385-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanyi, D., Ansink, A., Groeneveld, E., Hageman, P.C., Mooi, W.J., and Heintz, A.P. (1989). New monoclonal antibodies recognizing epidermal differentiation-associated keratins in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Keratin 10 expression in carcinoma of the vulva. J. Pathol. 159, 7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, J., Engeli, S., Gorzelniak, K., Luft, F.C., and Sharma, A.M. (2002). Mature adipocytes inhibit in vitro differentiation of human preadipocytes via angiotensin type 1 receptors. Diabetes 51, 1699-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto, A., Asahara, T., and Losordo, D.W. (2002). Transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization. Cardiovasc. Radiat. Med. 3, 221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K. et al. (2003). Circulating numbers of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with gastric and breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 198, 83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling, M., and Estrov, Z. (2003). Adult stem cells for tissue repair—a new therapeutic concept? N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 570-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D.S., Theise, N.D., Collector, M.I., Henegariu, O., Hwang, S., Gardner, R., Neutzel, S., and Sharkis, S.J. (2001). Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell 105, 369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., Gustafson-Brown, C., Hanks, S.K., Nason, K., Arbeit, J.M., Pogliano, K., Wisdom, R.M., and Johnson, R.S. (2003). c-Jun is essential for organization of the epidermal leading edge. Dev. Cell 4, 865-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightner, V.A. (1994). Tenascin: does it play a role in epidermal morphogenesis and homeostasis? J. Invest. Dermatol. 102, 273-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas-Szabowski, N., Stark, H.J., and Fusenig, N.E. (2000). Keratinocyte growth regulation in defined organotypic cultures through IL-1-induced keratinocyte growth factor expression in resting fibroblasts. J. Invest. Dermatol. 114, 1075-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe, Y., Toda, S., Miyazaki, K., and Sugihara, H. (2003). Mature adipocytes, but not preadipocytes, promote the growth of breast carcinoma cells in collagen gel matrix culture through cancer-stromal cell interactions. J. Pathol. 201, 221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitaka, T. (2001). Hepatic stem cells: from bone marrow cells to hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281, 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll, R., Franke, W.W., Schiller, D.L., Geiger, B., and Krepler, R. (1982). The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell 31, 11-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D.C., Shafaee, S., Lee, D., and Bikle, D.D. (2000). Requirement of an AP-1 site in the calcium response region of the involucrin promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24080-24088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlmeier, S., Kastaniotis, A.J., Hiltunen, J.K., and Bergmann, U. (2004). The yeast mitochondrial proteome, a study of fermentative and respiratory growth. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3956-3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ootani, A., Toda, S., Fujimoto, K., and Sugihara, H. (2003). Foveolar differentiation of mouse gastric mucosa in vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 1905-1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, B.E., Bowen, W.C., Patrene, K.D., Mars, W.M., Sullivan, A.K., Murase, N., Boggs, S.S., Greenberger, J.S., and Goff, J.P. (1999). Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science 284, 1168-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheinwald, J.G., and Green, H. (1975). Formation of a keratinizing epithelium in culture by a cloned cell line derived from a teratoma. Cell 6, 317-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata, M. et al. (2002). Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 8, 403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J.W., Cairns, J.M., and Gasseling, M.T. (1957). The role of apical ectodermal ridge of ectoderm in the differentiation of the morphological structure of and inductive specificity of limb parts of the chick. J. Morphol. 101, 57-88. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, H., Toda, S., Miyabara, S., Kusaba, Y., and Minami, Y. (1991). Reconstruction of the skin in three-dimensional collagen gel matrix culture. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 27A, 142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, H., Toda, S., Yonemitsu, N., and Watanabe, K. (2001). Effects of fat cells on keratinocytes and fibroblasts in a reconstructed rat skin model using collagen gel matrix culture. Br. J. Dermatol. 144, 244-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suurmeijer, A.J., van der Wijk, J., van Veldhuisen, D.J., Yang, F., and Cole, G.M. (1999). Fractin immunostaining for the detection of apoptotic cells and apoptotic bodies in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. Lab. Invest. 79, 619-620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabowski, A., Maas-Szabowski, N., Andrecht, S., Kolbus, A., Schorpp-Kistner, M., Fusenig, N.E., and Angel, P. (2000). c-Jun and JunB antagonistically control cytokine-regulated mesenchymal-epidermal interaction in skin. Cell 103, 745-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda, S., Nishimura, T., Yamada, S., Koike, N., Yonemitsu, N., Watanabe, K., Matsumura, S., Gartner, R., and Sugihara, H. (1999). Immunohistochemical expression of growth factors in subacute thyroiditis and their effects on thyroid folliculogenesis and angiogenesis in collagen gel matrix culture. J. Pathol. 188, 415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda, S., Yonemitsu, N., Minami, Y., and Sugihara, H. (1993). Plural cells organize thyroid follicles through aggregation and linkage in collagen gel culture of porcine follicle cells. Endocrinology 133, 914-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, A., and Ferguson, M.W. (2003). Wound healing: a model of dermal wound repair. Methods Mol. Biol. 225, 249-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, S. (1998). Keratinocyte growth factor: a unique player in epithelial repair processes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 9, 153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, G., Steinhoff, C., Schulz, R., Scheller, M., Vingron, M., Ropers, H.H., and Nuber, U.A. (2003). Gene expression profile of mouse bone marrow stromal cells determined by cDNA microarray analysis. Cell Tissue Res. 311, 227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, B.S., Harris, S., Waseem, N.H., Lane, D.P., and Jones, D.B. (1992). A study of cell proliferation in formalin-fixed, wax-embedded bone marrow trephine biopsies using the monoclonal antibody PC10, reactive with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). J. Pathol. 166, 45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk, P.A. et al. (2002). Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4279-4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]