Abstract

With the development of nanotechnology, the application of nanomaterials in the field of drug delivery has attracted much attention in the past decades. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as promising drug nanocarriers have become a new area of interest in recent years due to their unique properties and capabilities to efficiently entrap cargo molecules. This review describes the latest advances on the application of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in drug delivery. In particular, we focus on the stimuli-responsive controlled release systems that are able to respond to intracellular environmental changes, such as pH, ATP, GSH, enzyme, glucose, and H2O2. Moreover, drug delivery induced by exogenous stimuli including temperature, light, magnetic field, ultrasound, and electricity is also summarized. These advanced technologies demonstrate current challenges, and provide a bright future for precision diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: mesoporous silica nanoparticle, drug delivery system, controlled release, stimuli-responsive, chemotherapy

Introduction

Chemotherapy is a common cancer treatment approach that uses chemotherapeutic agents to kill cancer cells.1 High-dose conventional chemotherapeutic agents could not only rapidly kill growing cancer cells, but also non-specifically distribute in the whole body where they affect both cancerous and normal cells, thereby limiting the accumulated dose within the tumor cells and resulting in undesirable treatment due to excessive toxicities.2 Whereas an inadequate dose will limit its effectiveness and result in incomplete treatment and stingy recovery period. Thus, delivery of drugs at an optimal dosage and appropriate duration will make them more effective and powerful in cancer therapy. To overcome this hurdle, a widely pursuit strategy is to design a target-specific and controlled drug-delivery system (DDS) that can transport an effective dosage of drug molecules to the targeted tissues and release the drugs in a sustainable manner.3 The main challenge of such DDS is its ability to carry an effective amount of drugs with no effects or significantly decreased side effects than those of current therapy approaches.

Recently, nanomaterials have attracted increasing attentions in the fields of drug delivery. Over the past decades, several nano-sized DDSs have been developed and applied by targeted drug delivery to cancer cells, such as liposomes,4–7 polymeric micelles,8–11 dendrimers,12–16 carbon nanotubes,17–22 inorganic nanoparticles,23–26 and silica-based materials.27–31 Among them, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have attracted much attention due to their unique physiochemical properties, such as large specific surface area and pore volume, controllable particle size, remarkable stability and biocompatibility, and high drug-loading capacity. In 1992, scientists at the Mobil Corporation synthesized ordered mesoporous silica nanomaterials, and this discovery was recognized as a critical breakthrough in material science that could lead to a variety of applications ranging from food manufacturing to pharmaceutical technology.32

In 2001, Vallet-Regí et al33 published their first report on the application of MSN as a DDS for controlled drug release. Ibuprofen (IB), an extensively employed analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug, was loaded into the MSN and the release process was recorded. Results proved that up to 30 wt% of IB could be loaded into the MSN, and MSN showed a sustained drug release feature. With a gradually increase in studies, a series of MSN-based stimuli-responsive systems have been reported.34,35 The drug release is subsequently to be triggered by environmental stimuli including physical signals (eg, temperature,36,37 electricity,38 magnetic field,39 and photons40–42) and chemical signals (eg, pH values,43 redox potential,44–46 and enzymatic activities47,48).

In this review, we intend to discuss about the advanced progress related to MSN for drug delivery associated with special focus on environmental responsive mechanisms and highlight the effect of endogenous stimuli in drug delivery such as pH, redox, enzyme, ATP, glucose, and H2O2, as well as exogenous stimuli including thermo, light, ultrasound, and magnetic field. We have also summarized current challenges that need to be addressed in order to bring this highly promising MSN to practical uses as drug-delivery vehicles in the bright upcoming future.

Endogenous stimuli-responsive drug delivery

Endogenous stimuli are intrinsic conditions of cancerous tissues such as a tough redox condition, an acidic environment, and presence of certain types of enzymes. The design of nanocarriers sensitive to endogenous stimuli may represent an attractive alternative for targeted and controlled drug delivery. In this section, we will discuss DDS that takes advantage of variations in pH value, redox potential, active enzymes, ATP, glucose, and H2O2.

pH-responsive drug delivery

Among the various stimuli-responsive DDS, pH-triggered drug release attracted much attention since it is well documented that the pH in tumor and inflammatory tissues is more acidic (pH 6.0–7.0) than that in blood and normal tissue (pH 7.4), with even lower pH values in some organelles, such as endosomes (pH 5.5) and lysosomes (pH <5.5).49 Thus, the abnormal pH gradients combined with the advantages of MSN provide opportunities to design nanocarriers that are sensitive to physiopathological pH signals to trigger selective drug release in cancer cells. A number of studies have reported the developments of pH-responsive MSN nanocarriers through surface functionalization of MSN with various materials as gatekeepers. The triggered release of anti-cancer drugs from MSN nanopores was achieved mainly by using polyelectrolytes, supramolecular nanovalves, pH-sensitive linkers, and acid-decomposable inorganic materials.

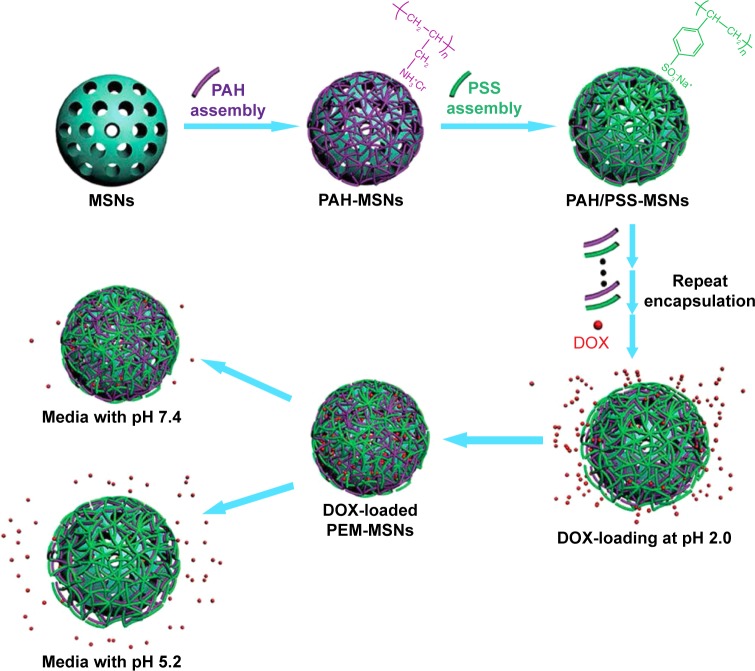

Polyelectrolyte is a commonly used blocking material in pH-responsive drug delivery. Feng et al50 constructed an MSN-based pH-responsive DDS with polyelectrolyte multilayers. Polyallylamine hydrochloride and polystyrene sulfonate were coated onto the surface of MSN via a layer- by-layer technique, and doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) was loaded into the nanopores of the as-prepared polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM)-MSN. The biocompatibility and the influence of the layer numbers on the release profiles were evaluated. A schematic illustration of the construction and release mechanism of PEM-MSN is shown in Figure 1. Results showed that there was a tendency of layer thickness–dependent drug release, and MSN with 20 layers exhibited the highest DOX release rate. Moreover, MSN at acidic condition (pH 5.2) showed a significant higher drug release rate than those at neutral condition (pH 7.4). Popat et al51 reported a core-shell pH-responsive nanocarrier based on surface coating onto phosphonate-functionalized MSN. The coating was realized by phosphoramidate covalent bonding between phosphonate groups on the MSN surface and amino groups on chitosan. IB was loaded as a model drug. Only approximately 20% of IB was released in pH 7.4 due to chitosan’s low degradability and solubility. Whereas ~90% of IB was released in the first 8 hours when the pH value decreased to 5, below the isoelectric point (pI =6.3) of chitosan. Chitosan as a polycation led to the fast dissolution and burst drug release. Hu et al52 also investigated the chitosan-capped MSN as pH-responsive nanocarriers for controlled drug release. Recently many studies reported efficient pH-responsive delivery systems using other polyelectrolytes as gatekeepers, such as poly-4-vinyl pyridine,53 poly [2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate],54 polyacrylic acid,55,56 poly(methyl acrylic acid),57 and poly-L-glutamic acid.58 Thus, the tumor tissues with weak acidity make pH-responsive release systems suitable for controlled release of anti-cancer drugs.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration for the fabrication of pH-responsive carrier systems based on PEM-MSN.

Notes: The polyelectrolyte pairs of PAH/PSS were alternately deposited onto the MSN surface via the LBL technique, DOX was then loaded into the mesoporous channels and inside the polymer shell of PEM-MSN at pH 2.0, thus constructing a pH-responsive drug-delivery system from which the release of DOX is accelerated under acidic conditions. Reproduced from Feng W, Zhou X, He C, et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayer functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for pH-responsive drug delivery: layer thickness-dependent release profiles and biocompatibility. J Mater Chem B. 2013;9:5886–5898, DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C3TB21193B, with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.50

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; PAH, polyallylamine hydrochloride; PSS, polystyrene sulfonate; LBL, layer by layer; DOX, doxorubicin hydrochloride; PEM, polyelectrolyte multilayer.

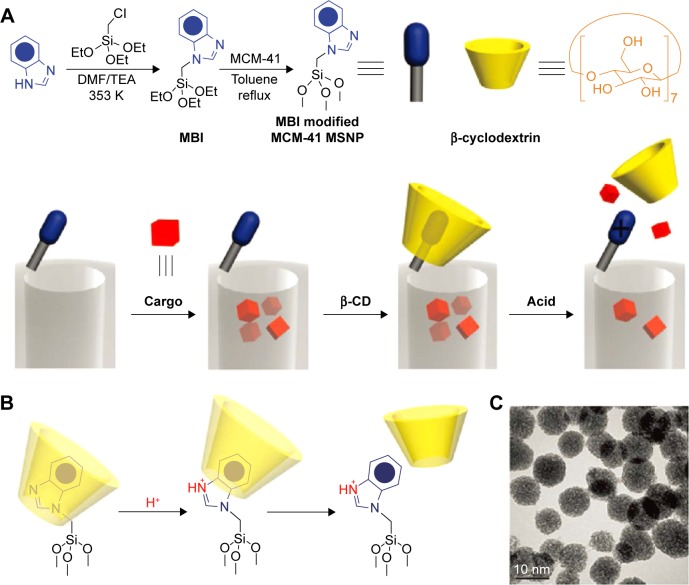

In addition, the application of supramolecule was also reported as a gatekeeper to develop pH-responsive DDS for controlled cargo release such as pseudorotaxanes, rotaxanes, and analogues.59–63 Herein, the aromatic amines/ammonium stalks were immobilized on the MSN surface, and mobile cyclic molecular gates were introduced to encircle the stalks via non-covalent interactions for controlling the transport of the model drugs loaded in the nanopores.64 Under certain conditions (especially acidic conditions), the weak binding constant between cyclic caps and stalks resulted in large-amplitude sliding motions of the caps and burst drug release. Li et al64 have developed several pH-responsive mesoporous silica DDS utilizing the pH-dependent pseudorotaxanes and rotaxanes. In 2009, they constructed a β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) and N-methylbenzimidazole-based pH-responsive MSN DDS, as shown in Figure 2. N-methylbenzimidazole was immobilized onto the MSN surface to serve as stalks and β-CD was introduced to encircle the stalks and form a polypseudorotaxane complex.59 The nanovalves remain closed at pH 7 with no cargo leakage; however, by decreasing the pH to 5, a rapid release of the guest molecules was detected. Upon the drug-loaded MSN was internalized by THP-1 and KB-31 cells, the acidic pH in lysosome triggered the decomposition of the nanovalves and resulted in an observable drug release. Park et al63 also reported a cyclodextrin (CD) rotaxane-based pH-responsive DDS, in which the guest molecules were entrapped in the pores of MSN and then polyetherimide (PEI)/CD poly pseudorotaxane was grafted onto the surface to block the nanopores. PEI was used as the guest polymer for CD hosts. At a pH of 11, a stable poly pseudorotaxane complex formed by PEI and α/γ-CD tightly covered the MSN and blocked the pore of the MSN to make the guest molecules reside in the pores. On decreasing the pH values to 5.5, a burst release of guest molecule was observed, which was attributed to the dissociation of CD rings from the PEI stalks due to the weak interaction of the protonated PEI chain with the hydrophobic interior of CDs.

Figure 2.

A graphical representation of the pH-responsive MSNP nanovalve.

Notes: (A) Synthesis of the stalk, loading of the cargo, capping of the pore, and release of the cap under acidic conditions. The average nanopore diameter of the MSNP is ~2.2 nm and the periphery diameter of the secondary side of β-cyclodextrin is ~1.5 nm. Thus, for a cargo with a diameter >0.7 nm, a single nanovalve should be adequate to achieve effective pH-modulated release. (B) Details of the protonation of the stalk and release of the β-cyclodextrin. (C) TEM image of capped MSNP. The scale bar is 10 nm. Reprinted with permission from Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, et al. Autonomous in vitro anticancer drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles by pH-sensitive nanovalves. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(36):12690–12697. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.59

Abbreviations: TEM, transmission emission tomography; β-CD, β-cyclodextrin; MSNP, Mesoporous silica nanoparticle, MBI, 1-Methyl-1H-benzimidazole.

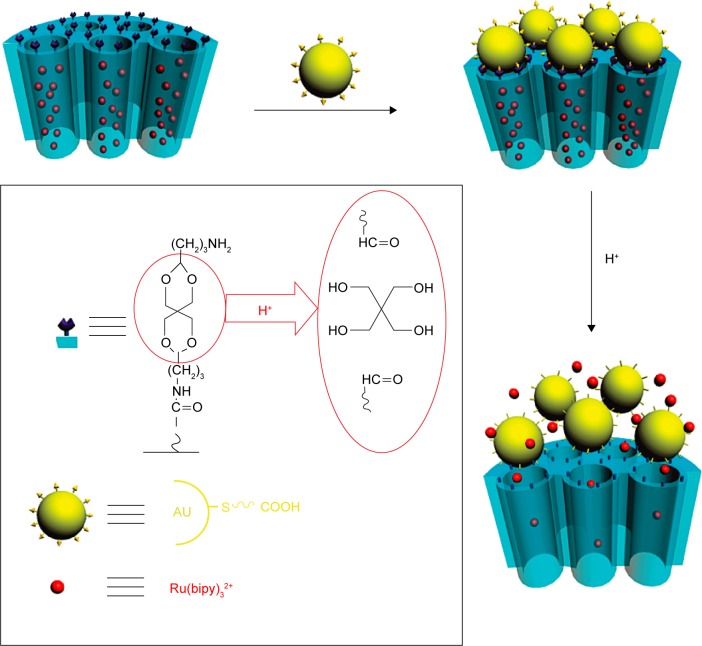

The pH-sensitive linkers, such as acetal bond,65–67 hydrazine bond,68–71 hydrazone bond,72 and ester bond,73,74 can be cleaved under acidic condition, thus providing opportunities for designing pH-responsive DDS applied in cancer treatment. Liu et al65 reported a new pH-responsive nanocarrier by capping gold nanoparticles onto the surface of mesoporous silica through acid-labile acetal linkers (Figure 3). [Ru(bipy)3]Cl2 dye was loaded as a model drug to investigate the pH-responsive release behavior, and the dye-loaded MSN was dispersed in water at different pH values to test the release profiles. At pH 7.0, no free dye was observed as the intact acetal linker and gold nanoparticles blocked the nanopores to inhibit cargo release. However, the solution at pH 4.0 induced a quick release of dye molecules and almost 100% dye molecules were totally released in 13 hours. On decreasing the pH to 2.0, an even faster molecular transport was observed with 90% release within 30 minutes and reached equilibrium in 2 hours. Similarly, a pH-responsive nanocarrier was designed by Chen et al66 via capping graphene quantum dot (GQD) onto the nanopores of mesoporous silica through an acid-cleavable acetal bond. The amount of drug leaked from GQD@MSN remained negligible (nearly 3.5%) after 24 hours of incubation, indicating that GQD caps can efficiently block the nanopores. However, ~48% and 86% of the drug molecule were released when the pH value decreased to 5.0 and 4.0, respectively. The accelerated DOX release was ascribed to the cleavage of the acetal bond under the acidic conditions and the continuous separation of GQDs from MSN. Besides that, hydrazine bond is another widely studies acid-labile linkers. Li et al68 reported a novel intelligent DDS by conjugation of DOX to MSN through acid-labile hydrazone bonds. Results showed that ~15% of DOX was released after 100 hours of incubation at pH 7.4. However, a much faster release rate was observed when the pH value decreased to 6.5, and approximately 55% of DOX was released after 100 hours. To further decrease the pH value to 5.0 in order to simulate the pH condition in endosomes and lysosomes, ~60% of DOX was released in the first 10 hours, and 90% of DOX was released after 100 hours of incubation, which was attributed to the acidic conditions induced cleavage of hydrazone bond uncapped the sealing materials from the MSN.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of pH-responsive nanogated ensemble based on gold-capped mesoporous silica through acid-labile acetal linker.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Agarwal A, Mueller LJ, Feng P. pH-responsive nanogated ensemble based on gold-capped mesoporous silica through an acid-labile acetal linker. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1500–1501. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.65

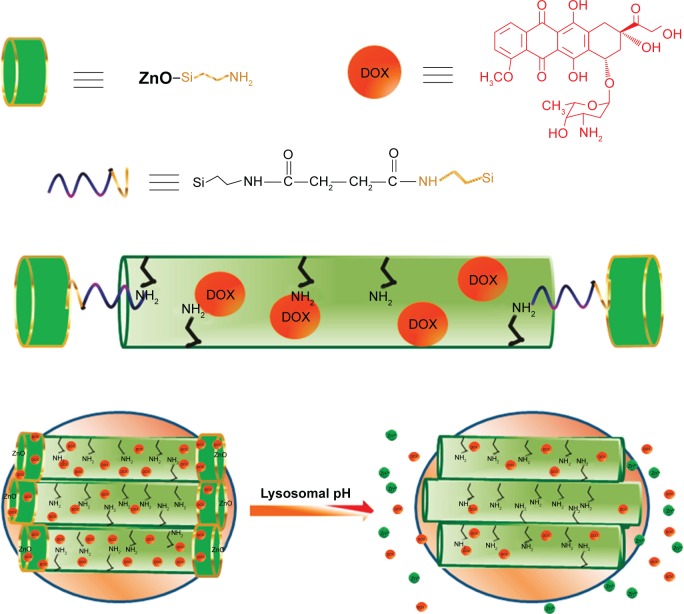

Acidic-decomposable inorganic materials have been reported as gatekeepers to control drug release, offering opportunities to design promising pH-responsive DDS for therapeutic applications. Muhammad et al75 reported a pH-responsive DDS based on acid-decomposable, luminescent ZnO quantum dots (QDs)-capped MSN to inhibit premature drug release (Figure 4). Following cellular uptake by HeLa cells, the ZnO QDs were fast dissolved in the acidic intracellular condition that resulted in a burst drug release into the cytosol. In this research, the ZnO QDs behaved not only as a cap but also as a synergistic antitumor drug for efficient cancer therapy, as the dissolved Zn2+ would induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage. Rim et al76 developed absorbable calcium phosphate (CaP)-capped MSN-based pH-responsive DDS for controlled drug release. Under acidic conditions, the entrapped drugs within the nanopores would be released via the dissolution of the capped CaP. To record the release profiles, the drug loaded nanocarriers were immersed at different pH conditions, and the results showed a fast DOX release rate under low pH conditions (pH 4.5) after 24 hours compared to physiological pH (pH 7.4). Furthermore, the pH-dependent dissolution kinetics of hydroxyapatite-like coating from the DOX-Si-MP-CaP complex was also investigated to support the DOX release profiles. The increased Ca2+ concentration further confirmed that the dissolution of pore blocker resulted in the open of the pores and then triggered DOX release.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of ZnO@MSN-DOX and working protocol for pH-triggered release of the DOX from ZnO@MSN-DOX to the cytosol via selective dissolution of ZnO QDs in the acidic intracellular compartments of cancer cells.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Muhammad F, Guo M, Qi W, et al. pH-Triggered controlled drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles via intracelluar dissolution of ZnO nanolids. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(23):8778–8781. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.75

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin hydrochloride; QDs, quantum dots.

Redox-responsive drug delivery

The development of redox-responsive vehicles for targeted intracellular drug/gene delivery is a very efficient cancer therapeutic strategy. The basic principle of redox-responsive DDS is based on the significant differences in redox concentrations between tumors and normal tissues. It is well documented that concentration of reducing agents such as glutathione (GSH) existing in tumor cells is approximately three times higher than that in normal cells.77 As a redox-sensitive group, the disulfide bond (S–S) could be easily cleaved in the presence of GSH, which makes it an attracting receptor site in the design of redox-responsive DDS. Since Lai et al44 reported the first redox-responsive DDS using CdS nanoparticles to block the pore entrances of mesoporous silica through a disulfide bond, several capped systems driven by GSH and other reducing agents (such as dithiothreitol, DTT) have been described. To establish redox-responsive DDS, disulfide bonds were absolutely necessary, and the gatekeepers may vary, but mainly based on nanoparticles,44,45,78,79 supramolecule or biomacromolecule,80–88 and polymers.89–94

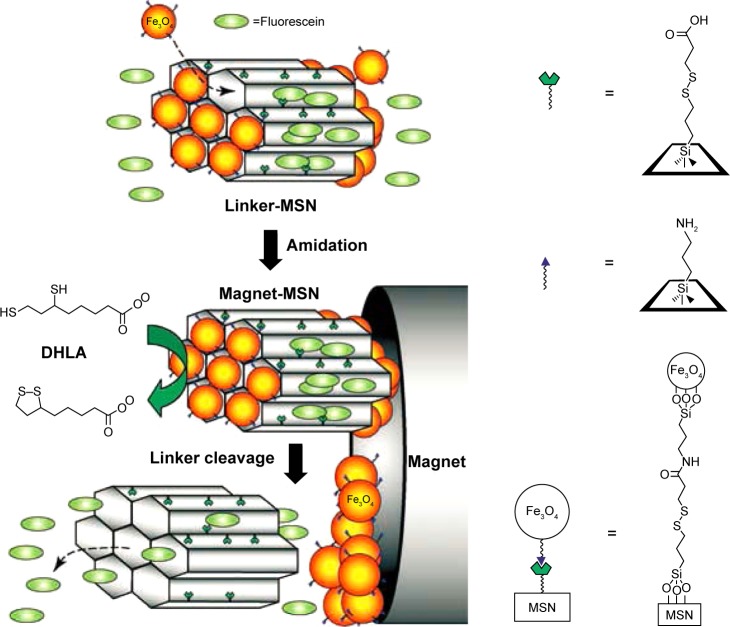

Many inorganic nanoparticles have been used as nanovalves to seal the drug molecule into the channels of MSN through covalently functionalizing MSN with disulfide containing linkers, such as CdS,44 Fe3O4,45 gold,78 and ZnO.79 Giri et al45 synthesized a controlled-release delivery system that was based on MCM-41-type MSN capped with superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles through disulfide bonds and was stimuli-responsive and chemically inert to guest molecules entrapped in the matrix.45 As shown in Figure 5, the disulfide bonds between the MSN and the Fe3O4 nanoparticles are labile and could be cleaved with disulfide reducing agents (DTT) to release the trapped guest molecules from the mesopores.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the redox-responsive delivery system (magnet-MSN) based on mesoporous silica nanorods capped with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles.

Notes: The controlled-release mechanism of the system is based on the reduction of the disulfide linkage between the Fe3O4 nanoparticle caps and the linker-MSN hosts by reducing agents such as DHLA. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Giri S, Trewyn BG, Stellmaker MP, Lin VS. Stimuli-responsive controlled-release delivery system based on mesoporous silica nanorods capped with magnetic nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl.45 Copyright © 2005 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DHLA, dihydroplipoic acid.

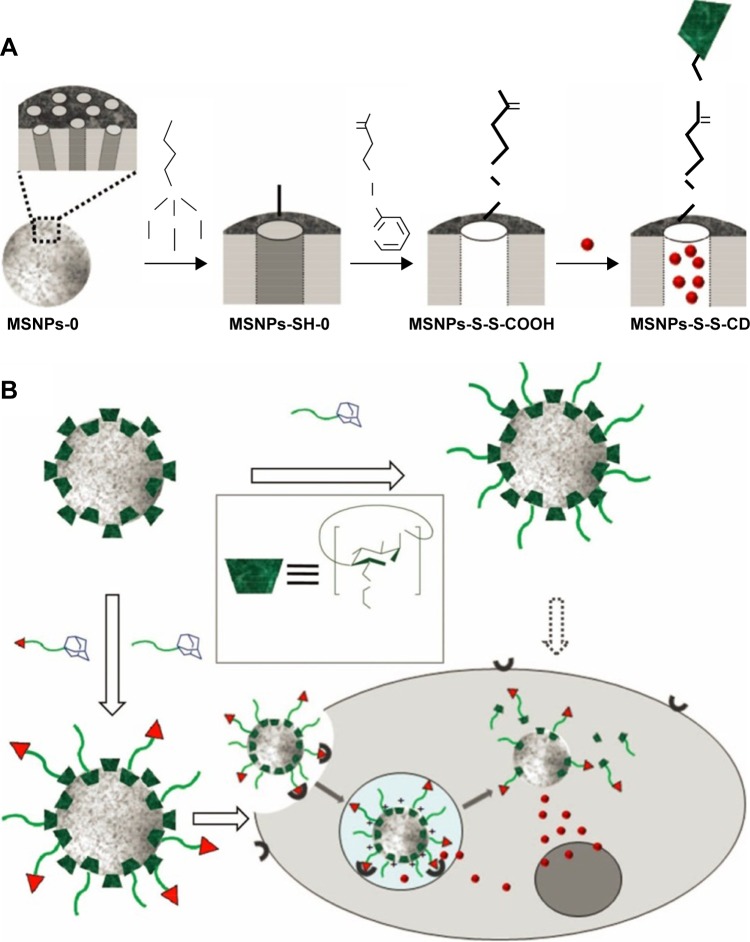

Moreover, some supramolecule can also be introduced as gatekeeper onto the surface of MSN. As illustrated in Figure 6, Zhang et al80 reported redox-responsive nano-gated MSN by grafting β-CD or adamantane onto the nanopores of MSN through disulfide. After the drug-loaded nanoparticles internalized and then escaped from the endosome to diffuse into the cytoplasm of cancer cells, the high concentration of GSH in the cytoplasm leads to the removal of the β-CD/adamantane caps by cleaving the pre-installed disulfide bonds, further promoting the release of drugs from the nanocarriers.80,81 Similarly, some biomacromolecules including collagen,84 cytochrome c,85 peptides,86 hyaluronic acid,87 and heparin88 can also be covalently immobilized onto the surface of MSN through disulfide-containing linker and act as gatekeeper for controlled drug release.

Figure 6.

(A) Synthetic representation of the cargo-loaded MSNPs-S-S-CD. Reaction conditions: 1) MPTMS in toluene; 2) 2-carboxyethyl-2-pyridyl disulfide in ethanol, followed by the removal of the surfactant CTAB; 3) loading of cargo molecules, followed by additions of β-CD(NH2)7 and 1-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC⋅HCl). MSNPs-0 and MSNPs-SH-0 mean that the mesopores are occupied with the CTAB template. (B) Schematic illustration of multifunctional MSNPs-CD-PEG-FA for targeted and controlled drug delivery. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Zhang Q, Liu F, Nguyen KT, et al. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer-targeted and controlled drug delivery. Adv Funct Mater.80 Copyright © 2012 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: β-CD, β-cyclodextrin; MSNPs, mesoporous silica nanoparticles; CD, cyclodextrin; MPTMS, (3-Mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane; CTAB; cetyltrimethylammonium bromide.

Polymers are the most popular organic materials used for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Gong et al89 successfully synthesized redox-sensitive MSN functionalized with polyethylene glycol (PEG) through a disulfide bond linker. Results showed that drug release was markedly accelerated with the increasing concentration of GSH, while PEG-functionalized system maintained close at low GSH concentrations. Other reports using PEG as gatekeepers also showed similar results.90–92 Liu et al95 reported a redox-responsive DDS by using cross-linked poly N-acryloxysuccinimide as a gatekeeper. Poly N-acryloxysuccinimide was anchored to the outlet of silica mesopore through reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. The loaded molecules were released from the hybrid materials by the cleavage of the disulfide linker of the polymeric network with the addition of disulfide reducing agents DTT. It is believed that the developments of such a biocompatible system with non-covalent polymer-gatekeepers in MSN-based nanocarriers provide a versatile method for hydrophilic drug delivery and enhance the effectiveness of cancer therapy.

Enzyme-responsive drug delivery

The upregulated expression profile of specific enzymes in pathological conditions such as cancer or inflammation makes it an interesting stimulus to achieve enzyme-mediated drug release.96 Recently, the developments of enzyme-triggered DDS based on functionalized MSN have attracted much attention.

Patel et al97 designed an enzyme-responsive snap-top covered SiO2 nanocarriers. MSN with an azide-terminated surface was achieved by alkylating amine-modified MSN with a tri(ethylene glycol) monoazide monotosylate motif. The α-CD tori was then threaded onto the tri(ethylene glycol) chains at low temperature (at 5°C) to effectively block the nanopores, while the azide served as a handle to attach a stoppering group that was chemically attached to the snap-top precursors using the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Porcine liver esterase was designed to test the viability of an enzyme-responsive snap-top motif by catalyzing the hydrolysis of an adamantyl ester stopper, which resulted in a dethreading of the α-CD and quick release of the cargo molecules from the pores. Similarly, Sun et al98 developed a sulfonatocalix[4]arene (SC[4]A)-capped enzyme-responsive DDS through enzyme cleavage bonds onto the surface of mesostructured silica. These versatile systems are capable of entrapment and controlled release of cargo molecules in response to three different types of exogenous stimuli, such as enzyme, pH variation, and addition of competitive binding agent. In the presence of esterase and urease, SC[4]A-capped MSN showed a rapid cargo release.

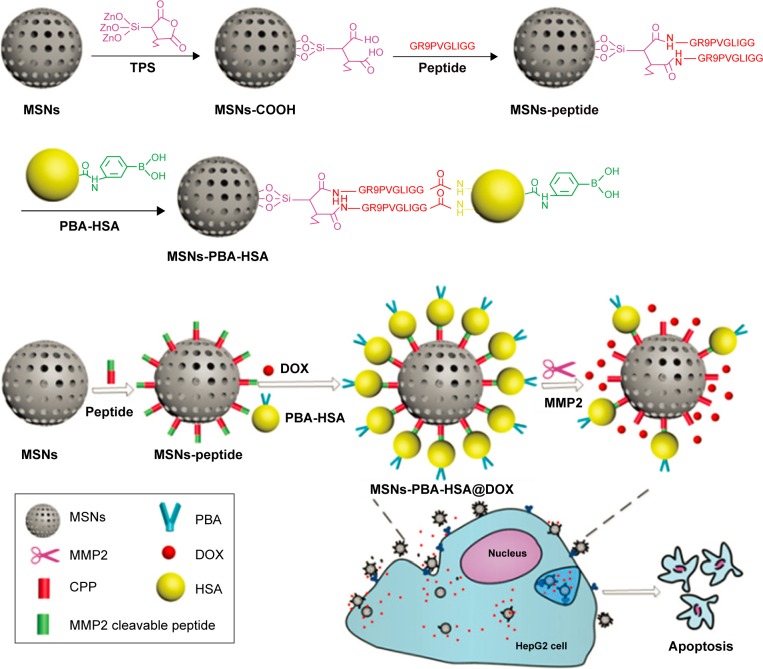

As one of the important physiological changes in the tumor microenvironment, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP2 and MMP9, are overexpressed in almost all the types of cancer cells and associated with tumor invasiveness, metastasis, and angiogenesis, whereas they are minimally expressed in healthy tissues.99–106 Recently, specific protease-sensitive peptide sequences have been designed as linkers that allow the controlled release of chemotherapeutics from MSN. van Rijt et al101 developed avidin-capped MSN functionalized with linkers that could be specifically cleaved by MMP9, thereby allowing controlled release of chemotherapeutics from MSN in high MMP9-expressing lung tumor cells. The avidin-capped MSN demonstrated an efficient protease sequence-specific release of the incorporated chemotherapeutic cisplatin and a rapid tumor cell apoptosis. Liu et al102 reported phenyl boronic acid–conjugated human serum albumin (PBA-HSA)-capped MSN for MMPs-responsive drug delivery. As shown in Figure 7, PBA-HSA was grafted onto the surfaces of MSN as a sealing agent via an intermediate linker of a functional MMP2 cleavable peptide. When the MSN-based DDS reaches the tumor site, the overexpressed MMP2 in the tumor microenvironment breaks down the intermediate linker and releases the drugs to induce cell apoptosis in vitro and inhibit tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of the functionalization routes of an MSN-based drug-delivery system and its enzyme-mediated biological responses.

Note: Reproduced from Liu J, Zhang B, Luo Z, et al. Enzyme responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted tumor therapy in vitro and in vivo. Nano scale. 2015;7(8):3614–3626,102 with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry, DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201201316.

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; MMP, matrix metalloprotein; PBA, phenyl boronic acid; HSA, human serum albumin; DOX, doxorubicin hydrochloride; CPP, cell penetration peptide; TPS, 3-triethoxysilylpropylsuccinic anhydride.

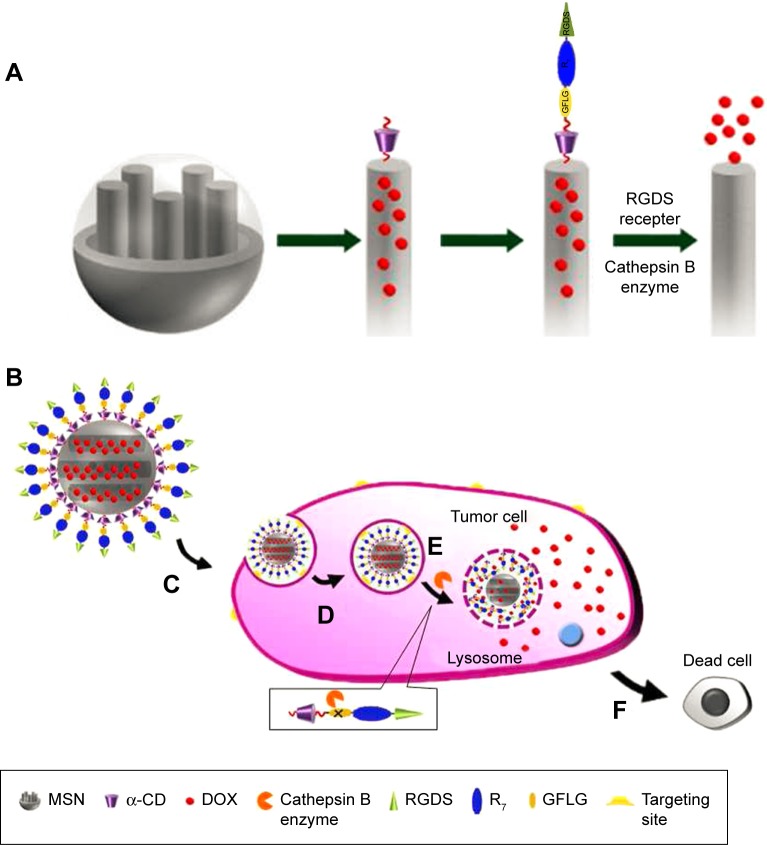

Cathepsin B is another kind of protease that is widely used for enzyme-responsive drug release. As a late endosomal and lysosomal protease that can specifically hydrolyze Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly (GFLG) sequence, cathepsin B is overexpressed in various types of tumors.107,108 Cheng et al109 reported an MSN-based cathepsin-B responsive DDS. As described in Figure 8, the classic rotaxane structure formed with alkoxysilane tether and α-CD was employed to anchor onto the orifices of MSN to serve as gatekeeper and further modified with multi-functional peptide azido-GFLGR7RGDS for drug loading, tumor targeting, and cathepsin B responsive functions. The functional nanoparticles could specifically target and internalize to HeLa cells, and the overexpressed cathepsin B in endosomes and lysosomes could specifically hydrolyze the GFLG sequences to switch on the nanovalves and resulted in ~80% release of the loaded DOX within 24 hours. Furthermore, in vitro cellular experiments indicated that DOX-loaded MSN resulted in a high rate of cell apoptosis. Li et al110 also obtained similar results by using enzyme-responsive cell-penetrating peptides to functionalize silica nanoparticles.

Figure 8.

(A) Functionalization procedure of the MSN. (B) Drug-loaded MSN under physiological condition. (C) RGDS-targeted to the tumor cell. (D) Endocytosis into specific tumor cell. (E) Cathepsin B enzyme-triggered drug release in cytoplasm. (F) Apoptosis of the tumor cell. Reprinted with permission from Cheng YJ, Luo GF, Zhu JY, et al. Enzyme-induced and tumor-targeted drug delivery system based on multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(17):9078–9087. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.109

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin hydrochloride; α-CD, α-cyclodextrin; RGDS, Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser; GFLG, Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly.

Also, other enzyme-responsive DDSs have been reported. Bernardos et al48 synthesized lactose-capped silica nanoparticles that could be selectively uncapped using β-D-galactosidase by the cleavage of a glycosidic bond. Thornton and Heise111 described enzyme-mediated release of guest molecules from silica nanoparticles coated with a bioactive peptide shell. In the presence of elastase, specific enzymatic hydrolysis of the peptide shell removes the bulky peptide-terminated Fmoc groups, permitting the selective release of the entrapped guest molecules. Schlossbauer et al47 described the use of biotin–avidin complex for biomolecule-based, enzyme-responsive drug release and demonstrated the mechanism of action of this system with controlled release of guest molecules as a result of enzymatic hydrolysis of trypsin. These representative examples highlight the potential of enzyme-triggered drug delivery.

Glucose-responsive drug delivery

Glucose-responsive materials have attracted much attention in recent years due to their capability of competitive combination with glucose, which shows great potential application in drug delivery.112

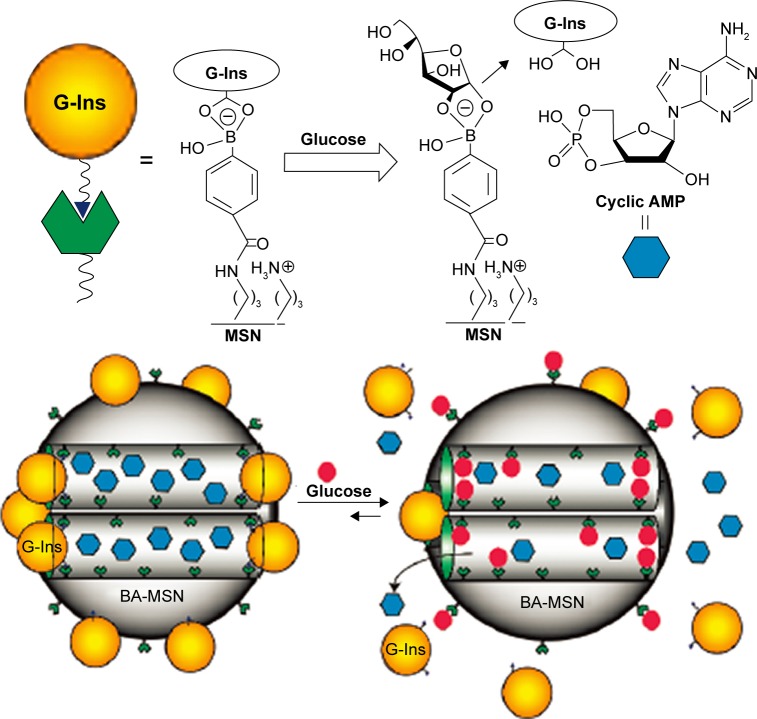

Zhao et al113 reported the synthesis of a glucose-responsive MSN-based double delivery system for both insulin and cyclic AMP with precise control over the sequence of release. As depicted in Figure 9, gluconic acid–modified insulin (G-Ins)8 proteins were immobilized on the exterior surface of boronic acid-functionalized MSN through reversible covalent bonding between phenyl boronic acid and vicinal diols of FITC-G-Ins, giving rise to the desired FITC-G-Ins-MSN material and also serving as caps to encapsulate cyclic AMP molecules inside the mesopores of MSN. It is well known that phenyl boronic acid can form much more stable cyclic esters with the adjacent diols of saccharides than with acyclic diols. The release of both G-Ins and cyclic AMP from MSN could be triggered by introducing glucose to cleave the linkage between FITC-G-Ins and boronic acid-functionalized MSN. This glucose-responsive drug release system was expected to be a novel and promising therapeutic strategy to cure diabetes in the future, instead of the frequently used insulin injection approach.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the glucose-responsive MSN-based delivery system for controlled release of bioactive G-Ins and cyclic AMP.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Cheng YJ, Zhao Y, Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Lin VS. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based double drug delivery system for glucose-responsive controlled release of insulin and cyclic AMP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(24):8398–8400. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.113

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; G-Ins, gluconic acid–modified insulin; BA-MSN, boronic acid-functionalized MSN.

Chen et al114 reported a glucose-responsive controlled- release system based on the competitive combination between glucose oxidase, glucosamine, and glucose. MSN was first functionalized with D-(+)-glucosamine to act as an anchor and then capped with glucose oxidase to seal the preloaded rhodamine B. The controlled release of the entrapped guest molecules could be realized through effective competitive combination with glucose to open the nanovavles of MSN.

Zhao et al115 introduced a novel glucose-responsive controlled release of insulin system by coating glucose oxidase and catalase multilayers onto the surface of MSN. The MSN serves as a drug reservoir and the glutaraldehyde cross-linked enzymatic multilayers act as a valve to control the release of insulin in response to the exogenous glucose level.

H2O2-responsive drug delivery

The main culprit in the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion injury is the overproduction of ROS. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is the most abundant form of ROS produced during ischemia/reperfusion, which usually induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and triggers apoptosis, leading to the oxidative damage of tissues.116–118 Therefore, targeting H2O2 as a diagnostic marker and therapeutic agent shows great potentials.

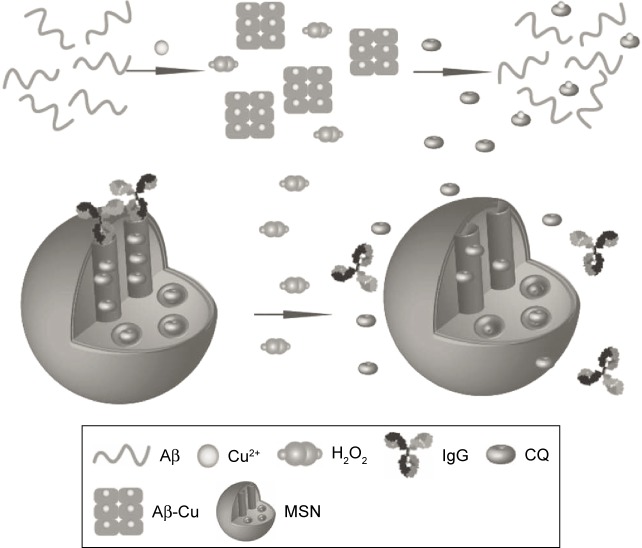

Geng et al119 reported a biocompatible and H2O2-responsive controlled-release system to realize target delivery of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic metal chelator. As illustrated in Figure 10, the system was consisted of a mesoporous nanoparticle functionalized with a derivative of aryl boronic acids by forming stable cyclic esters with the adjacent diols of saccharides. Human immunoglobulin G (IgG) was chosen as a nanoscopic cap. The delivery of the entrapped guest molecules depended on the oxidization of the aryl boronic esters to phenols in the presence of H2O2. The complete breakage of aryl boronic esters resulted in the release of IgG and guest molecules, and the release rate was sensitive to H2O2 concentration. Negligible guest molecules were released in the absence of H2O2 at room temperature, indicating that IgG acted as an efficient cap for guest molecules retention. Whereas with increasing H2O2 concentrations of 5 mM, approximately 91% of the guest molecules were released after 12 hours of incubation, which was attributed to the rupture of boronate ester bonds that link the MSN and IgG to the opening of the nanovalves. This novel kind of delivery system shows a potential application in controlled drug release.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of H2O2-induced release of guest molecules clioquinol (CQ) from the pores of MSN capped with IgG.

Notes: CQ can chelate Cu2+ to disassemble Aβ plaques and inhibit H2O2 production. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Geng J, Li M, Wu L, Chen C, Qu X. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based H2O2 responsive controlled-release system used for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Adv Healthc Mater.119 Copyright © 2012 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; IgG, immunoglobulin G; Aβ, amyloid-beta.

ATP-responsive drug delivery

As one of the important biogenic molecules, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a multifunctional nucleotide that provides ubiquitous energy for all biological processes, including muscle contraction, cells function, synthesis and degradation of essential cellular compounds, and membrane transport, by breaking the phosphoanhydride bond. There is growing evidence that the upregulated ATP levels are correlated with many pathological processes, such as chemoresistance, uncontrolled tumor growth, and synaptic transmission in neurons,120,121 which make it a significant marker in distinguishing cancerous cells from normal cells. Owning to the upregulated ATP level, many researchers have tried to design ATP-responsive drug-release systems that can specifically recognize ATP as well as the competitive binding with ATP aptamer.122–126

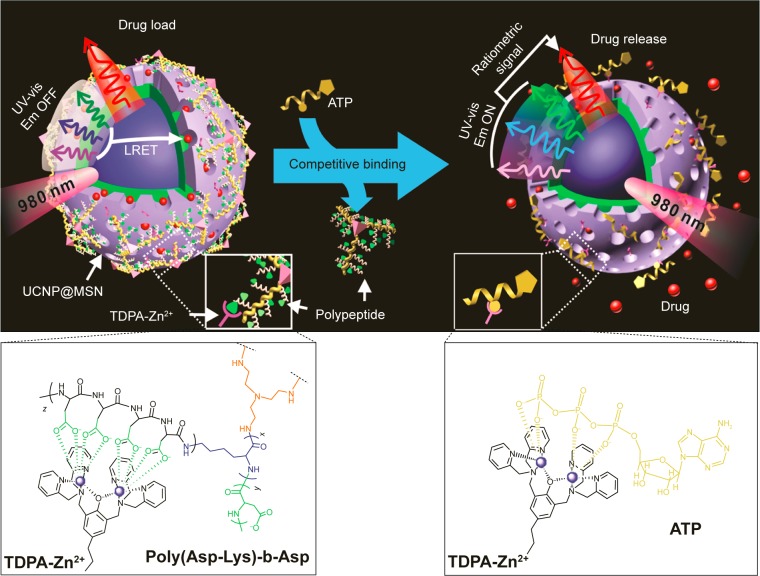

Lai et al122 developed an ATP-responsive DDS for real-time monitoring of drug release. As shown in Figure 11, the mesoporous-silica-coated up-conversion nanoparticle (UCNP@MSN) was wrapped with a compact branched polypeptide, poly(Asp-Lys)-b-Asp, and then functionalized with zinc-dipicolylamine analogue (TDPA-Zn2+) on its exterior surface. In the absence of ATP, the loaded drugs remained entrapped within the UCNP-MSN due to the multivalent interactions between Asp moieties in the polypeptide and the TDPA-Zn2+ complex present on the surface of UCNP-MSN. Whereas in the presence of ATP, a competitive displacement of the surface-bound polypeptide by ATP due to its higher affinity to TDPA-Zn2+ was observed, which led to the opening of the channel and sustained drug release. He et al designed a facile ATP-responsive controlled release system consisting of MSN functionalized with aptamers as a cap.123 In this system, the ATP aptamer was first hybridized with arm single-stranded DNA1 (arm ssDNA1) and arm single-stranded DNA2 (arm ssDNA2) to form a sandwich-type DNA structure and then grafted onto the MSN surface through click chemistry approach, which resulted in blocked guest molecules in the nanopores. Seven hours after the addition of ATP (20 mM), ~83.2% of the total load guest molecule was released due to the aptamer-containing sandwich-type DNA structure was dissociated through a competitive binding with ATP, leaving the flexible arm ssDNA1 and ssDNA2 on the surface of MSN. Zhu et al124 reported an ATP-responsive MSN-dependent drug-release system based on aptamer target interactions. The pores of MSN were capped with ATP aptamer-modified Au nanoparticles. In the presence of ATP molecule, a competitive displacement reaction occurred, the Au nanoparticles were uncapped from the MSN, and the cargo was released.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the real-time monitoring of ATP-responsive drug release from polypeptide-wrapped TDPA-Zn2+-UCNP@MSN.

Notes: Small molecule drugs were entrapped within the mesopores of the silica shell by branched polypeptide capping the pores through a multivalent interaction between the oligo-aspartate side chain in the polypeptide and the TDPA-Zn2+ complex on nanoparticles surface. The UV-vis emission from the multicolor UCNP under 980 nm of excitation was quenched because of the LRET between the loaded drugs and the UCNP. Addition of small molecular nucleoside-polyphosphates such as ATP led to a competitive binding of ATP to the TDPA-Zn2+ complex, which displaced the surface-bound compact polypeptide because of the high binding affinity of ATP to the metallic complex. The drug release was accompanied with an enhancement in the UV-vis emission of UCNP, which allows for real-time monitoring of the drug release via a ratiometric signal using the NIR emission of UCNP as an internal reference. Reprinted with permission from Lai J, Shah BP, Zhang Y, Yang L, Lee KB. Real-time monitoring of ATP-responsive drug release using mesoporous-silica-coated multicolor upconversion nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015;9(5):5234–5245. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.122

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; UV-vis, ultraviolet-visible; UCNP, up-conversion nanoparticle; TDPA-Zn2+, zinc-dipicolylamine analogue; Em, emission; LRET, luminescence resonance energy transfer; NIR, near infrared.

Exogenous stimuli-responsive drug delivery

Unlike endogenous stimuli, exogenous stimuli are carried out via an external physical treatment. Although this approach seems unappealing, exogenous stimuli-responsive DDSs might be more encouraging and favorable due to the heterogeneous physiological conditions of human population. In this section, drug delivery triggered by externally applied stimuli, including temperature changes, magnetic fields, ultrasounds, and light and electric fields, are discussed.

Thermo-responsive drug delivery

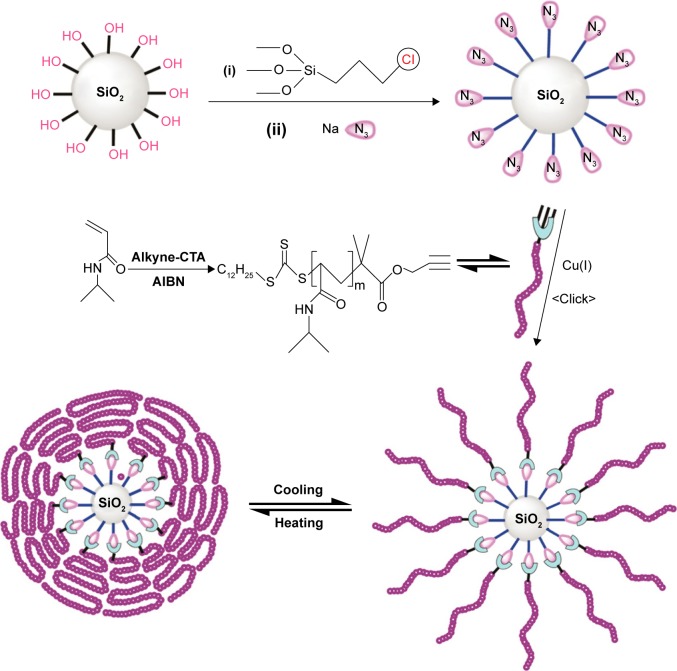

Thermo-responsive drug delivery is one the most investigated stimuli-responsive strategies and has been widely explored in tumor therapy.127 Thermo-responsive MSN DDSs are usually composed of MSN and surface-coated thermo-responsive materials. The drug release was closely dependent on the variation of the surrounding temperature to control the switch of the nanovalves. Poly N-isopropyl acrylamide (PNIPAM) has been well known as a thermo-responsive polymer. As depicted in Figure 12, Chen et al128 reported a thermo-responsive DDS synthesized by covalent functionalization of silica nanoparticles with PNIPAM by a combination of reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer and click chemistry. The thermal-induced conformational changes of the NIPAM polymer layer on the exterior surface of the MSN could be used as a switch to control the cargo release. When the temperature increases above 30°C, PNIPAM acquires hydrophobic character and the chains of polymers aggregated on the SiO2 surface and the drug molecule are blocked in the nanopores of MSN. At a temperature between 25°C and 30°C, the outer zone of PNIPAM brushes still remains hydrophilic and the chains of polymers are extended and swollen in an aqueous solution. Thus, the entrapped drug could be quickly released. Singh et al129 developed a temperature-sensitive MSN for triggered drug release by a relatively simple technique. The anionic surface of MSNPs was functionalized with bifunctional N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide hydrochloride, and the acrylamide group was subsequently covalently cross-linked to NIPAM and poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate by radical copolymerization at room temperature. DOX was used as a model drug molecule and the polymer-coated MSN showed a high drug-loading capability (~50% of total DOX added). At temperatures (37°C) greater than the lower critical solution temperature (LCST, 31°C), approximately 50% DOX was released within the first 2 hours, which is relatively higher than those maintained at room temperature. Other researchers also investigated the PNIPAM-based thermo-responsive DDS using MSN as the drug container.130–136 This new core-shell thermo-responsive nanocarrier showed promising potential in controlled drug/gene delivery.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of hybrid silica nanoparticles coated with thermoresponsive PNIPAM brushes via RAFT polymerization and click chemistry.

Notes: Reprinted with permission from Chen J, Liu M, Chen C, Gong H, Gao C. Synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles with well-defined thermoresponsive PNIPAM via a combination of RAFT and click chemistry. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3(8):3215–3223. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.128 The expression of (i) and (ii) indicates the addition order of the reaction materials.

Abbreviations: PNIPAM, poly N-isopropyl acrylamide; RAFT, reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer; AIBN, azobisisobutyronitrile.

Moreover, researchers have tried to employ nuclear acid as gatekeeper to develop thermo-responsive DDS. The double-stranded DNA has been recognized as attractive capping materials due to their unique self-recognition properties of duplex DNA, as well as temperature-dependent assembly. As reported by Schlossbauer et al,37 Chen et al,137 and Chang et al,138 duplex DNA strand or oligonucleotide was anchored onto the openings of the nanovalves and was utilized as a cap for blocking the guest molecules within the porous channels. The duplex DNA cap could be denatured by DNA strand melting at a specific melting temperature of the oligonucleotide, thus opening the valves and releasing the cargo.

In general, the biggest challenge in designing thermo-responsive nanocarriers lies in the development of novel materials that are safe and sensitive enough to respond to slight temperature changes around the physiological temperature of 37°C.

Light-responsive drug delivery

Due to their non-invasiveness property and the possibility of remote spatiotemporal control, a variety of light-responsive systems have been developed in recent years to achieve on-demand drug release in response to light irradiation at a specific wavelength (in the ultraviolet [UV], visible, or near-infrared regions). The mechanism relies on the photo-sensitiveness-induced conformational transition of the nano-carriers.

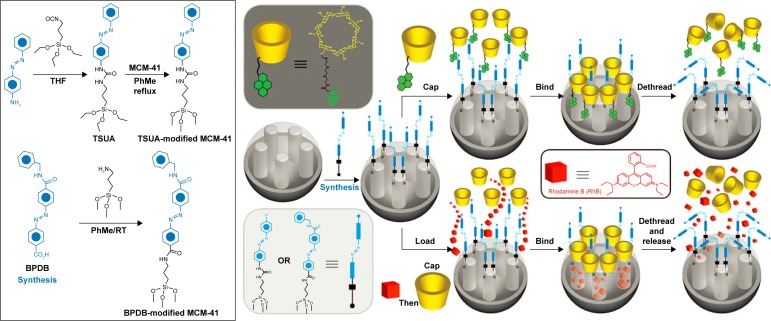

Azobenzene (AB) is a type of light-sensitive molecule. When irradiated with UV light at a wavelength of 351 nm, AB is able to isomerize from the more-stable trans to a less-stable cis configuration. Previous studies have demonstrated that there was a high binding affinity between β-CD and trans-AB derivatives and a low binding affinity between β-CD and cis-AB derivatives in aqueous solutions.139,140 According to this principle, a lot of AB-liable light-responsive DDSs were designed.41,42,141–143 Ferris et al42 developed AB-derivative-dependent DDS and MSN-based light-responsive DDS. As shown in Figure 13, two different AB derivatives, prepared from 4-(3-triethoxysilylpropylureido) azobenzene and (E)-4-((4-(benzylcarbamoyl)phenyl) diazenyl) benzoic acid, were used to modify MSN and act as stalks. Then, pyrene-modified β-CD was threaded onto the stalks that bind to trans-AB units to cap the nanopores and seal the preloaded model drug molecule. Upon irradiation with UV light of 351 nm, isomerization of AB units from trans form to cis form occurs, which leads to the dissociation of β-CD rings from the stalks, uncapping the container and releasing the cargo outside.

Figure 13.

Synthesis of TSUA- and BPDB-modified MCM-41.

Notes: Two approaches to the operation and function of the AB-modified MCM-41 NPs carrying nanovalves. Py-β-CD or β-CD threads onto the trans-AB stalks to seal the nanopores. Upon irradiation (351 nm), the isomerization of AB units from trans to cis leads to the dissociation of Py-β-CD or β-CD rings from the stalks, thus opening the gates to the nanopores and releasing the cargo. Reprinted with permission from Ferris DP, Zhao YL, Khashab NM, Khatib HA, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Light-operated mechanized nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(5):1686–1688. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.42

Abbreviations: TSUA, 4-(3-triethoxysilylpropylureido) azobenzene; BPDP, (E)-4-((4-(benzylcarbamoyl)phenyl)diazenyl) benzoic acid; β-CD, β-cyclodextrin; AB, azobenzene, NP, nanoparticle; THF, tetrahydro furan; RT, room temperature; PhMe, toluene.

Coumarin is also an attractive photo-responsive molecule. Mal et al144 described an UV light-induced reversible drug-release system for the first time. 7-[(3-Trihydroxysilyl) ropoxy]coumarin was attached to the silanol groups of cholestane-loaded MSN that acted as “hinged double doors” to block the drug molecules in the nanopores. When the system was irradiated at the UV light wavelength greater than 310 nm, coumarin underwent a photodimerization reaction and cyclobutane dimer rings were formed that spanned the pores to hinder drug diffusion. Whereas when the system was irradiated with UV light of wavelength of ~250 nm, cyclobutane rings were photocleaved, yielding new coumarin monomers to release the entrapped drug molecules. Guardado-Alvarez et al145 introduced a light-responsive DDS based on photolabile coumarin-based molecules. Coumarin-based molecules were bound to the surface of MSN, and then bulky β-CD molecules were non-covalently associated with the substituted coumarin molecules, blocking the pores and preventing the cargo diffusion. Upon one-photon excitation at 376 nm or two-photon excitation at 800 nm, the bond that bound coumarin to the nanopore was cleaved, which resulted in the fast release of both the CD cap and cargo molecules.

The major drawback of light-triggered drug delivery is its low penetration depth (~10 mm) in UV-visible region (wavelength <700 nm). However, it is possible to replace UV-visible light with near infrared (NIR) laser (range 700–1,000 nm), which showed deeper tissue penetration effect, lower scattering properties, and minimal harm to tissues.

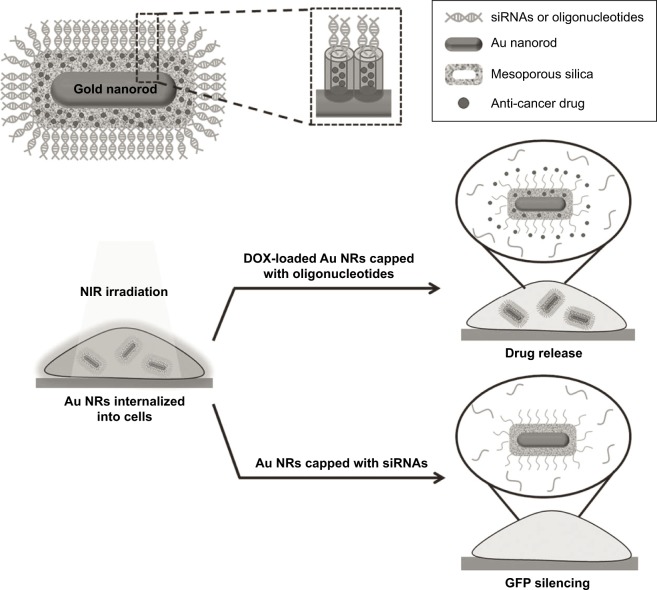

Gold nanoparticles presented plasmonic properties and showed high efficiency to transform NIR radiation into thermal energy. Chang et al138 have reported an NIR light-responsive oligonucleotide-gated ensembles for intracellular drug delivery. As depicted in Figure 14, the system is composed of gold nanorods–encapsulated MSN and surface-decorated DNA double strands as gatekeepers. When this device was irradiated with NIR laser (808 nm, 1.5 W/cm2), the generated heat enables denaturing of the duplex oligonucleotides of the DNA strands opening the pores and allowing the drugs to diffuse out of the carrier. Yang et al146 developed a novel multifunctional NIR-stimulus-controlled drug-release system based on gold nanocages as photothermal cores, mesoporous silica shells as supporters to increase the anticancer drug loading, and thermo-responsive PNIPAM as NIR-stimulus gatekeepers (Au-nanocage@ mSiO2@PNIPAM). The Au nanocage cores can effectively absorb and convert light into heat upon irradiation with an NIR laser, thereby resulting in the collapse of the PNIPAM shell covering the surface of mesoporous silica and exposing the nanochannels outside, realizing the triggered release of entrapped DOX. Vivero-Escoto et al147 synthesized a gold nanoparticle-capped MSN-based intracellular DDS for photo-induced controlled release of an anticancer drug.

Figure 14.

Schematic illustration of Au nanorods (Au NRs) with an oligonucleotide-capped silica shell and the corresponding near infrared (NIR) light-controlled intracellular drug and siRNA release.

Note: Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Chang YT, Liao PY, Sheu HS, Tseng YJ, Cheng FY, Yeh CS. Near-infrared light-responsive intracellular drug and siRNA release using Au nanoensembles with oligonucleotide-capped silica shell. Adv Mater.138 Copyright © 2012 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

There are also other strategies to construct light-responsive DDS, such as grafting pore blockers using light-sensitive linkers or polymers, which suffer physicochemical changes or induced rupture under light irradiation.148–150

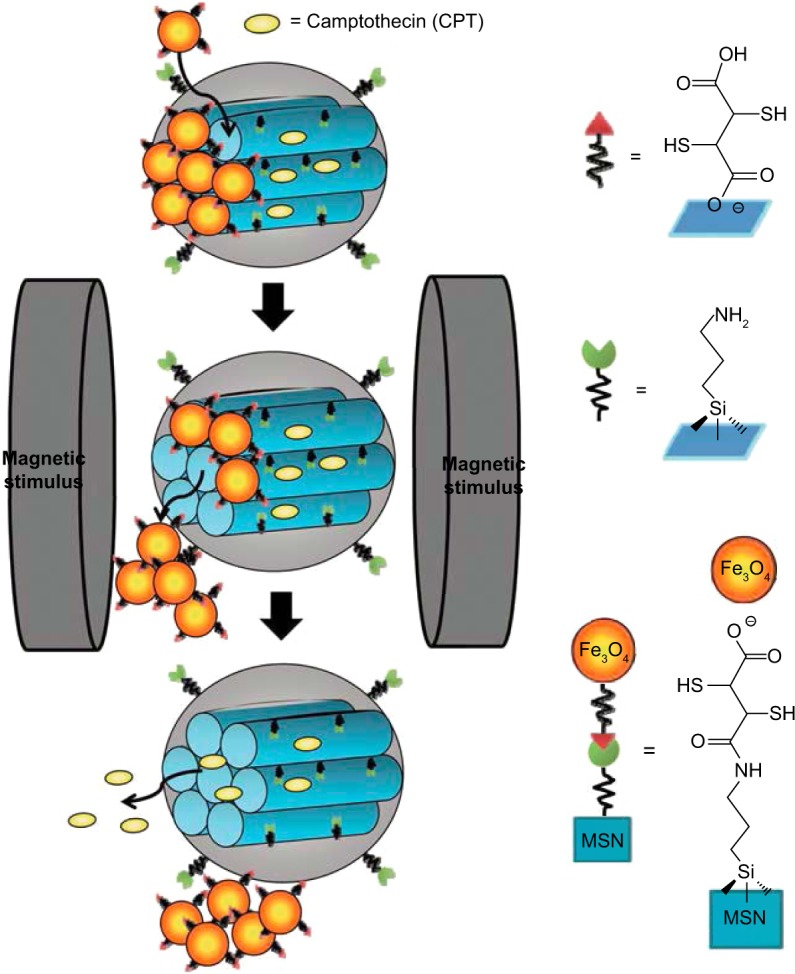

Magnetic-responsive drug delivery

Magnetic-responsive DDS relies on the delivery of magnetic and drug-loaded nanoparticles to the tumor site under the influence of external magnetic field. The external magnetic field can not only drive the magnetic nanoparticles to the desired location precisely, but also can act as an exogenous stimulus to induce the controlled drug release. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle is one of the most widely employed magnetic particles.

As illustrated in Figure 15, Chen et al151 constructed a novel nanocarrier (MSN@Fe3O4) using a facile technology by capping amine-modified MSN with 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid–functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles through chemical amidation. In the absence of magnetic field, a negligible amount of the drug was released from the MSN@Fe3O4. However, some nanocaps can be removed by breaking the chemical bonds when subjected to an external controllable magnetic field, which subsequently leads to a fast drug release. Also, the results showed that the release profiles were dependent on the strength and time duration. Moreover, MSN@Fe3O4 nanocarriers could perform well as T2-weighted magnetic resonance contrast enhancement agents for molecular imaging.

Figure 15.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis and structure of the Fe3O4 NPs-capped mesoporous silica drug nanocarriers.

Note: The drug release from MSN@Fe3O4 nanocarriers can be remotely controlled under a magnetic stimulus. Reproduced with permission from Chen PJ, Hu SH, Hsiao CS, Chin YY, Liu DM, Chen SY. Multifunctional magnetically removable nanogated lids of Fe3O4-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular controlled release and MR imaging. J Mater Chem. 2011;21(8):2535–2543. With permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.151 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C0JM02590A.

Abbreviations: NP, nanoparticle; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

Magnetic field–triggered drug release is usually dependent on the temperature, which is based on magnetic nanoparticle–embedded MSN that is capable of generating thermal energy under an external magnetic field so as to induce the conformational changes of the thermo-sensitive materials capped on the surface of MSN. Baeza et al152,153 developed a novel magnetic-responsive nanodevice that is able to control the release of small molecules and proteins in response to an alternating magnetic field. This device was based on iron oxide-encapsulated MSN and surface decorated with a temperature-sensitive NIPAM-based polymer. The copolymer was designed to act as thermo-responsive gatekeeper for the drug-loaded MSN and the release of the encapsulated drug could be modulated by the duration of the alternating magnetic field on–off states, which affects the shrinkage of the mesh size and the recovery of polymer. Cargos could be entrapped into nanocarriers at temperatures below LCST and released at temperatures above LCST. Under alternating magnetic field, the quickly enhanced temperature induced the conformational change of the surface-coated polymer to attain a more hydrophobic property thereby leading to a rapid release of the entrapped cargos.

Ruiz-Hernández et al154 also reported a magnetic- responsive DDS through double-helix DNA strand self-assembly to cap the nanochannels. Single-stranded DNA was immobilized onto the surface of thiol-/disulfide-functionalized MSN in which iron oxide superparamagnetic nanoparticles were encapsulated. The magnetic MSN was loaded with fluorescein as model drug molecule and subsequently capped with the complementary DNA strand. When exposed to an alternating magnetic field of 24 kA⋅m−1 and 100 kHz, the fluorescein-loaded particles could quickly heat the environment to reach hyperthermia in a few minutes, so as to induce progressive double-stranded DNA melting, giving rise to uncapping and subsequent drug release. Therefore, this novel strategy could play an important role in the development of thermo- and magnetic-responsive DDS against cancer.

Many other temperature-sensitive materials are also used as gatekeepers, such as lipid bilayer155 and pseudorotaxanes,39 and the heat generated from alternating magnetic field induced the disassembly of the blockers and sustained drug release.

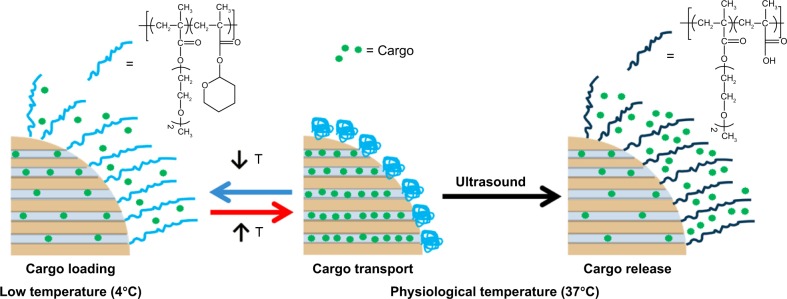

Ultrasound responsive drug delivery

Ultrasound is one of the most promising exogenous stimuli for drug delivery with the advantages of noninvasiveness, ability of deep tissue penetration, and controllable frequency.156 Moreover, ultrasonic irradiation could enhance drug release rate from both biodegradable and non-biodegradable polymer matrices.157

Paris et al developed a new ultrasound-responsive system based on MSN for controlled drug release.158 As illustrated in Figure 16, the temperature–ultrasound dual responsive random copolymer p(2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl methacrylate-co-tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate) was grafted on the MSN surface to act as gatekeeper, where 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl methacrylate is a kind of temperature-responsive monomer and tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate is a kind of ultrasound-responsive monomer. The temperature conversation is an on–off switch for model drug loading. At 4°C, 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl methacrylate showed a hydrophilic coil-like conformation and the model drug molecules could be diffused into the open nanopores, whereas at a temperature of 37°C, the hydrophobic polymer tightly collapsed onto the MSN to block the drug molecules in the nanopores. Upon ultrasound irradiation, the sensitive polymer changes its hydrophobicity and conformation toward coil-like gate-opening and cargo-releasing. Upon ultrasound irradiation with a frequency of and 1.3 MHz and power of 100 W at 37°, the hydrophobic tetrahydropyranyl methacrylate groups were hydrolyzed into hydrophilic methacrylic acid and methacrylic acid groups. This polarity change provokes the opening of the gates of the mesoporous channels resulting in a release of drug molecules. Kim et al159 reported a silica nanoparticle-based DDS that could be triggered by ultrasound. The system was composed of mesoporous silica as the drug reservoir and poly dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as gatekeeper to suppress the initial fast release. When the system was exposed to ultrasound for 10 minutes, sustained drug release was observed. These data confirmed that these hybrid MSNs can act as effective systems for ultrasound-responsive drug delivery.

Figure 16.

Schematic illustration of the behavior of dual-responsive release system in aqueous medium.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Paris JL, Cabañas MV, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. Polymer-grafted mesoporous silica nanoparticles as ultrasound-responsive drug carriers. ACS Nano. 2015;9(11):11023–11033. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.158

Abbreviation: T, temperature.

Electro-responsive drug delivery

Weak electric fields can be used to achieve pulsed or sustained drug release through a variety of actuation mechanisms with the advantages of simplicity, accurate dosage control, and easy coupling to bioelectronics. For instance, nanoparticles based on conductive polypyrrole exhibited tailored drug-release profiles as a result of a synergistic process of electrochemical reduction–oxidation and electric-field-driven movement of charged molecules.160 Zhao et al161 developed a tunable pH and electro-responsive drug release system based on chitosan-capped MSN. IB-loaded MSNs (IB-MSNs) were dispersed in chitosan solution and co-deposited with chitosan hydrogel on a titanium plate. The co-deposition was performed by immersing a titanium plate (as a cathode) and a platinum wire to the chitosan solution (pH~5) containing IB-MSN. After removal of the titanium plate from the chitosan solution, an opaque chitosan hydrogel with IB-MSN could be observed on the titanium plate and the stimuli-triggered IB release from chitosan/MSN complex hydrogel was studied. Results showed that the release of ibuprofen could be activated by applying a cathodic voltage (~ −5.0 V) to the titanium plate, resulting in a burst drug release and ~95% of the drug molecule was released in the first 3 hours. Also, this system showed a non-acid-dependent release manner, and a pH value of 7.4 and 10.0 accelerated the drug release, respectively.

Li et al162 established a dual thermo- and electro-responsive DDSs by coating functional macromolecules onto the outlets of MSN. The thermo-responsive moiety N-isopropylacrylamide was copolymerized with the electro-responsive moiety 4-nitrophenyl methacrylate (NPMA) to form a macromolecular coating on the surface of MSN. When exposed to an external electric field, the electro-sensitive NPMA could rotate and reorient its conformation, resulting in an increased drug release no matter whether the surrounding temperature was below or above the LCST.

Electrostimuli provide a new option in the design of the stimuli-triggered drug release and shows a promising potential in cancer therapy.

Conclusion

In this review, we have highlighted the advanced progress on mesoporous silica-based materials as stimuli-responsive controlled-release systems. The application of SiO2 particles in the preparation of stimuli-responsive DDS is mainly based on their biocompatibility, large surface area, high drug-loading capacity, nontoxicity, easy functionalization, and pore volume modulation. Moreover, it is simple to functionalize the surface of MSN with polymer/molecular ensembles to develop gated DDS. These smart DDS can be delivered into targeted cells and released drugs in some controlled manner by the exogenous stimuli including temperature, light, magnetic field, ultrasound, and electricity, as well as internal stimuli such as pH, ATP, GSH, enzyme, glucose, and H2O2. The application of MSN-based DDS shows great promise in biomedical applications such as bioimaging, disease diagnosis, and treatment which serves the precision and personalized therapy with high efficiency.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21575106), the Scientific Research Foundation for Returned Scholars, Ministry of Education of China, Zhejiang Qianjiang Talents Program and Wenzhou Government’s Start-up Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chabner BA, Roberts TG., Jr Timeline: chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho K, Wang X, Nie S, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1310–1316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ninomiya K, Kawabata S, Tashita H, Shimizu N. Ultrasound-mediated drug delivery using liposomes modified with a thermosensitive polymer. Ultrason Sonochem. 2014;21(1):310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mo R, Jiang T, Gu Z. Enhanced anticancer efficacy by ATP-mediated liposomal drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(23):5815–5820. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dicheva BM, ten Hagen TL, Seynhaeve AL, Amin M, Eggermont AM, Koning GA. Enhanced specificity and drug delivery in tumors by cRGD-anchoring thermosensitive liposomes. Pharm Res. 2015;32(12):3862–3876. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao H, Zhang Q, Yu Z, He Q. Cell-penetrating peptide-based intelligent liposomal systems for enhanced drug delivery. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2014;15(3):210–219. doi: 10.2174/1389201015666140617092552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding J, Chen L, Xiao C, Chen L, Zhuang X, Chen X. Noncovalent interaction-assisted polymeric micelles for controlled drug delivery. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50(77):11274–11290. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03153a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu L, Perche F, Wang T, Torchilin VP. Matrix metalloproteinase 2-sensitive multifunctional polymeric micelles for tumor-specific co-delivery of siRNA and hydrophobic drugs. Biomaterials. 2014;35(13):4213–4222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ke XY, Lin Ng VW, Gao SJ, Tong YW, Hedrick JL, Yang YY. Co-delivery of thioridazine and doxorubicin using polymeric micelles for targeting both cancer cells and cancer stem cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35(3):1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhaveri AM, Torchilin VP. Multifunctional polymeric micelles for delivery of drugs and siRNA. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:77. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C, Pan D, Luo K, et al. Dendrimer-doxorubicin conjugate as enzyme-sensitive and polymeric nanoscale drug delivery vehicle for ovarian cancer therapy. Polym Chem. 2014;5:5227–5235. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C, Pan D, Luo K, et al. Peptide dendrimer-doxorubicin conjugate-based nanoparticles as an enzyme-responsive drug delivery system for cancer therapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(8):1299–1308. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yavuz B, Pehlivan SB, Vural İ, Ünlü N. In vitro/in vivo evaluation of dexamethasone-PAMAM dendrimer complexes for retinal drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104(11):3814–3823. doi: 10.1002/jps.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra S, Noronha G, Dietrich S, Lang H, Bahadur D. Dendrimer-magnetic nanoparticles as multiple stimuli responsive and enzymatic drug delivery vehicle. J Magn Magn Mater. 2015;380:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Sun L, Pan L, et al. Dendrimer-like assemblies based on organoclays as multi-host system for sustained drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;88(3):706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H, Shi H, Zhang H, et al. Prostate stem cell antigen antibody-conjugated multiwalled carbon nanotubes for targeted ultrasound imaging and drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2014;35(20):5369–5380. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatnagar I, Venkatesan J, Kiml SK. Polymer functionalized single walled carbon nanotubes mediated drug delivery of gliotoxin in cancer cells. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(1):120–130. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Faraj A, Shaik AP, Shaik AS. Magnetic single-walled carbon nanotubes as efficient drug delivery nanocarriers in breast cancer murine model: noninvasive monitoring using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging as sensitive imaging biomarker. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;10:157–168. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S75074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siu KS, Zheng X, Liu Y, et al. Single-walled carbon nanotubes non-covalently functionalized with lipid modified polyethylenimine for siRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25(10):1744–1751. doi: 10.1021/bc500280q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karchemski F, Zucker D, Barenholz Y, Regev O. Carbon nanotubes-liposomes conjugate as a platform for drug delivery into cells. J Control Release. 2012;160(2):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Shi J, Jia X, et al. NIR-/pH-responsive drug delivery of functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes for potential application in cancer chemo-photothermal therapy. Pharm Res. 2013;30(11):2757–2771. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maleki Dizaj S, Barzegar-Jalali M, Zarrintan MH, Adibkia K, Lotfipour F. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery system. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12(10):1649–1660. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1049530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elbialy NS, Fathy MM, Khalil WM. Doxorubicin loaded magnetic gold nanoparticles for in vivo targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2015;490(1–2):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu J, Zhang R, Li J, et al. Fluorescent graphene quantum dots as traceable, pH-sensitive drug delivery systems. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:6709–6724. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S91864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You P, Yang Y, Wang M, Huang X, Huang X. Graphene oxide-based nanocarriers for cancer imaging and drug delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(22):3215–3222. doi: 10.2174/1381612821666150531170832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou J, Zhang W, Hong C, Pan C. Silica nanotubes decorated by pH-responsive diblock copolymers for controlled drug release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(6):3618–3625. doi: 10.1021/am507832n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiappini C, De Rosa E, Martinez JO, et al. Biodegradable silicon nanoneedles delivering nucleic acids intracellularly induce localized in vivo neovascularization. Nat Mater. 2015;14(5):532–539. doi: 10.1038/nmat4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohta S, Yamura K, Inasawa S, Yamaguchi Y. Aggregates of silicon quantum dots as a drug carrier: selective intracellular drug release based on pH-responsive aggregation/dispersion. Chem Commun (Camb) 2015;51(29):6422–6425. doi: 10.1039/c5cc00925a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, Chen Y, Ji X, et al. Controlled intracellular release of doxorubicin in multidrug-resistant cancer cells by tuning the shell-pore sizes of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5(12):9788–9798. doi: 10.1021/nn2033105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang H, Guo J, Sun Y, Chang B, Ren Q, Yang W. Facile synthesis of pH sensitive polymer-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their application in drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011;421(2):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kresge CT, Leonowicz ME, Roth WJ, Vartuli JC, Beck JS. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism. Nature. 1992;359:710–712. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vallet-Regi M, Rámila A, del Real RP, Pérez-Pariente J. A new property of MCM-41: drug delivery system. Chem Mater. 2001;13(2):308–311. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mamaeva V, Rosenholm JM, Bate-Eya LT, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for targeted inhibition of Notch signaling in cancer. Mol Ther. 2011;19(8):1538–1546. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo GF, Chen WH, Liu Y, Lei Q, Zhuo RX, Zhang XZ. Multifunctional enveloped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for subcellular co-delivery of drug and therapeutic peptide. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6064. doi: 10.1038/srep06064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aznar E, Mondragón L, Ros-Lis JV, et al. Finely tuned temperature-controlled cargo release using paraffin-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(47):11172–11175. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlossbauer A, Warncke S, Gramlich PM, et al. A programmable DNA-based molecular valve for colloidal mesoporous silica. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(28):4734–4737. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y, Liu H, Li F, et al. Dipolar molecules as impellers achieving electric-field-stimulated release. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1450–1451. doi: 10.1021/ja907560y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas CR, Ferris DP, Lee JH, et al. Noninvasive remote-controlled release of drug molecules in vitro using magnetic actuation of mechanized nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(31):10623–10625. doi: 10.1021/ja1022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang XJ, Liu X, Liu Z, Pu F, Ren J, Qu X. Near-infrared light-triggered, targeted drug delivery to cancer cells by aptamer gated nanovehicles. Adv Mater. 2012;24:2890–2895. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu YC, Fujiwara M. Installing dynamic molecular photomechanics in mesopores: a multifunctional controlled release nanosystem. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(13):2241–2244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferris DP, Zhao YL, Khashab NM, Khatib HA, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Light-operated mechanized nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(5):1686–1688. doi: 10.1021/ja807798g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu C, Yu L, Zheng Z, et al. Tannin as a gatekeeper of pH-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2015;5:85436–85441. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, et al. A mesoporous silica nanosphere-based carrier system with chemically removable CdS nanoparticle caps for stimuli-responsive controlled release of neurotransmitters and drug molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(15):4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giri S, Trewyn BG, Stellmaker MP, Lin VS. Stimuli-responsive controlled-release delivery system based on mesoporous silica nanorods capped with magnetic nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44(32):5038–5044. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H, Kim S, Park C, Lee H, Park HJ, Kim C. Glutathione-induced intracellular release of guests from mesoporous silica nanocontainers with cyclodextrin gatekeepers. Adv Mater. 2010;22(38):4280–4283. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlossbauer A, Kecht J, Bein T. Biotin-avidin as a protease-responsive cap system for controlled guest release from colloidal mesoporous silica. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(17):3092–3095. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernardos A, Aznar E, Marcos MD, et al. Enzyme-responsive controlled release using mesoporous silica supports capped with lactose. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(32):5884–5887. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tannock IF, Rotin D. Acid pH in tumors and its potential for therapeutic exploitation. Cancer Res. 1989;49(16):4373–4384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng W, Zhou X, He C, et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayer functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for pH-responsive drug delivery: layer thickness-dependent release profiles and biocompatibility. J Mater Chem B. 2013;9:5886–5898. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21193b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Popat A, Liu J, Lu GQ, Qiao SZ. A pH-responsive drug delivery system based on chitosan coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:11173–11178. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu X, Wang Y, Peng B. Chitosan-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles as pH-responsive nanocarriers for controlled drug release. Chem Asian J. 2014;9(1):319–327. doi: 10.1002/asia.201301105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niedermayer S, Weiss V, Herrmann A, et al. Multifunctional polymer-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for pH-responsive targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale. 2015;7(17):7953–7964. doi: 10.1039/c4nr07245f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun JT, Hong CY, Pan CY. Fabrication of PDEAEMA-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles and pH-responsive controlled release. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114(29):12481–12486. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan L, Tang Q, Yang D, Zhang JZ, Zhang F, Hu J. Preparation of pH-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their application in controlled drug delivery. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115(20):9926–9932. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xing R, Lin H, Jiang P, Qu F. Biofunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for magnetically oriented target and pH-responsive controlled release of ibuprofen. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2012;403:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen H, Guo J, Chang B, Yang W. pH-responsive composite microspheres based on magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticle for drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;84(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng J, Tian X, Sun Y, Lu D, Yang W. pH-sensitive poly(glutamic acid) grafted mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2013;450(1–2):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, et al. Autonomous in vitro anticancer drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles by pH-sensitive nanovalves. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(36):12690–12697. doi: 10.1021/ja104501a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao YL, Li Z, Kabehie S, Botros YY, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. pH-operated nanopistons on the surfaces of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(37):13016–13025. doi: 10.1021/ja105371u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angelos S, Khashab NM, Yang YW, et al. pH clock-operated mechanized nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(36):12912–12914. doi: 10.1021/ja9010157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du L, Song H, Liao S. A biocompatible drug delivery nanovalve system on the surface of mesoporous nanoparticles. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;147(1):200–204. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park C, Oh K, Lee SC, Kim C. Controlled release of guest molecules from mesoporous silica particles based on a pH-responsive polypseudorotaxane motif. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(9):1455–1457. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(7):2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Agarwal A, Mueller LJ, Feng P. pH-responsive nanogated ensemble based on gold-capped mesoporous silica through an acid-labile acetal linker. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1500–1501. doi: 10.1021/ja907838s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen T, Yu H, Yang N, Wang M, Ding C, Fu J. Graphene quantum dot-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles through an acid-cleavable acetal bond for intracellular drug delivery and imaging. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2(31):4979–4982. doi: 10.1039/c4tb00849a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Y, Ai K, Liu J, Sun G, Yin Q, Lu L. Multifunctional envelope-type mesoporous silica nanoparticles for pH-responsive drug delivery and magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials. 2015;60:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li ZY, Liu Y, Wang XQ, et al. One-pot construction of functional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for the tumor-acidity-activated synergistic chemotherapy of glioblastoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(16):7995–8001. doi: 10.1021/am402082d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng SH, Liao WN, Chen LM, Lee CH. pH-controllable release using functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as an oral drug delivery system. J Mater Chem. 2011;21(20):7130–7137. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang IP, Sun SP, Cheng SH, et al. Enhanced chemotherapy of cancer using pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticles to antagonize P-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(5):761–769. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin CH, Cheng SH, Liao WN, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for the improved anticancer efficacy of cisplatin. Int J Pharm. 2012;429(1–2):138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang F, Pauletti GM, Wang J, et al. Dual surface-functionalized Janus nanocomposites of polystyrene/Fe3O4@SiO2 for simultaneous tumor cell targeting and stimulus-induced drug release. Adv Mater. 2013;25(25):3485–3489. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun L, Zhang X, An J, Su C, Guo Q, Li C. Boronate ester bond-based core-shell nanocarriers with pH response for anticancer drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2014;4(39):20208–20215. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan L, Yang MY, Wu HX, et al. Glucose- and pH-responsive nanogated ensemble based on polymeric network capped mesoporous silica. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(11):6310–6316. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muhammad F, Guo M, Qi W, et al. pH-Triggered controlled drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles via intracelluar dissolution of ZnO nanolids. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(23):8778–8781. doi: 10.1021/ja200328s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rim HP, Min KH, Lee HJ, Jeong SY, Lee SC. pH-Tunable calcium phosphate covered mesoporous silica nanocontainers for intracellular controlled release of guest drugs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(38):8853–8857. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saito G, Swanson JA, Lee KD. Drug delivery strategy utilizing conjugation via reversible disulfide linkages: role and site of cellular reducing activities. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(2):199–215. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Torney F, Trewyn BG, Lin VS, Wang K. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles deliver DNA and chemicals into plants. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(5):295–300. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu S, Huang X, Du X. pH- and redox-triggered synergistic controlled release of a ZnO-gated hollow mesoporous silica drug delivery system. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(7):1426–1432. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01794c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Q, Liu F, Nguyen KT, et al. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer-targeted and controlled drug delivery. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(24):5144–5156. [Google Scholar]