Abstract

Background

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends triple therapy (long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists, long-acting beta-2 agonists, and inhaled corticosteroids) for patients with only the most severe COPD. Data on the proportion of COPD patients on triple therapy and their characteristics are sparse and dated. Objective 1 of this study was to estimate the proportion of all, and all treated, COPD patients receiving triple therapy. Objective 2 was to characterize those on triple therapy and assess the concordance of triple therapy use with GOLD guidelines.

Patients and methods

This retrospective study used claims from the IMS PharMetrics Plus database from 2009 to 2013. Cohort 1 was selected to assess Objective 1 only; descriptive analyses were conducted in Cohort 2 to answer Objective 2. A validated claims-based algorithm and severity and frequency of exacerbations were used as proxies for COPD severity.

Results

Of all 199,678 patients with COPD in Cohort 1, 7.5% received triple therapy after diagnosis, and 25.5% of all treated patients received triple therapy. In Cohort 2, 30,493 COPD patients (mean age =64.7 years) who initiated triple therapy were identified. Using the claims-based algorithm, 34.5% of Cohort 2 patients were classified as having mild disease (GOLD 1), 40.8% moderate (GOLD 2), 22.5% severe (GOLD 3), and 2.3% very severe (GOLD 4). Using exacerbation severity and frequency, 60.6% of patients were classified as GOLD 1/2 and 39.4% as GOLD 3/4.

Conclusion

In this large US claims database study, one-quarter of all treated COPD patients received triple therapy. Although triple therapy is recommended for the most severe COPD patients, spirometry is infrequently assessed, and a majority of the patients who receive triple therapy may have only mild/moderate disease. Any potential overprescribing of triple therapy may lead to unnecessary costs to the patient and health care system.

Keywords: COPD, triple therapy, severity, epidemiology, retrospective study

Introduction

COPD includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and is characterized by airflow limitation.1 A progressive respiratory disease, COPD symptoms include chronic cough, excessive sputum production, wheezing, dyspnea, and poor exercise tolerance.2

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD categorizes COPD patients into four groups (GOLD Groups A–D) based on symptomatic assessment, patients’ spirometric classification, and risk of exacerbations. GOLD recommends long-acting inhaled bronchodilators as first-line maintenance therapy for COPD patients in GOLD Groups A and B. This recommendation includes long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (LAMAs) and long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABAs), as either single or combination therapy.3 GOLD Group C patients have few symptoms but a high risk of exacerbations, and hence are recommended a fixed combination of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA or LAMA. Initiation of triple therapy, consisting of LAMA, LABA, and ICS, is reserved as an alternative treatment for GOLD Group D patients, those patients with the most severe form of COPD. GOLD Group D patients have severe or very severe airflow limitation (GOLD Grade 3 or 4), are highly symptomatic, and experience two or more exacerbations or at least one exacerbation that leads to a hospitalization per year.3

To date, there is no conclusive evidence on the superiority of triple therapy over other therapy options, particularly in patients at low risk of exacerbations.4 GOLD criteria advise that triple therapy be initiated in only a specific subgroup of patients, but doctors may not always follow these recommendations. However, overprescribing of triple therapy exposes patients to side effects of ICS, such as pneumonia.5 Additionally, triple therapy places an undue economic burden on patients who may have benefited from other less expensive mono- or dual-COPD medication regimens.

Real-world evidence suggests that prescribing patterns do differ from recommendations.6,7 A study by Mannino et al found that 64% of COPD patients were prescribed pharmacotherapy that did not adhere to GOLD recommendations.7 Among patients whose treatments were non-adherent to the GOLD criteria, 43% were undertreated and 57% were overtreated.7 GOLD-adherent prescribing was associated with significant reductions in the proportions of patients with all-cause hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits, as well as respiratory-specific ED visits, compared with non-adherent prescribing.7

There are limited real-world studies that describe the characteristics of patients with COPD who are prescribed triple therapy regimens in the US. Estimates of the proportion of COPD patients who receive triple therapy are sparse and dated. A study conducted using data from 2004 to 2005 found that 12.5% of commercially insured and 9.7% of Medicare patients diagnosed with COPD received triple therapy.8 A current understanding of the clinical characteristics, severity of disease, exacerbation history, and health care resource utilization (HRU) prior to triple therapy would provide valuable information to help characterize this population and to assess the concordance with GOLD recommendations for this type of treatment among patients with COPD. The objectives of this study were to quantify the use of triple therapy among patients with COPD and to characterize those treated with triple therapy to assess the concordance of triple therapy use with GOLD recommendations.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a noninterventional retrospective descriptive study done using the US administrative claims data. The data included enrollment, pharmacy, and medical claims from the IMS PharMetrics Plus database (IMS Health Incorporated, Danbury, CT, US). The IMS PharMetrics Plus database is composed of adjudicated claims for more than 150 million unique insured (both commercial and Medicare) enrollees across the US. Enrollees with both medical and pharmacy coverage in 2012 represented 40 million active lives. Patients in every metropolitan statistical area of the US are represented, with coverage of data from 90% of the US hospitals and 80% of all the US doctors, and representation from 85% of the Fortune 100 companies. All data are compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to protect patient privacy. The present study was approved as exempt from an Internal Review Board review by Ethical and Independent Review Services (Independence, MO). Written informed consent was not necessary as this retrospective study of de-identified data meets the criteria of the US Department of Health and Human Services guideline for protection of human subjects during research (45 CFR 46.101 b), clause (4).

Study population

Two separate cohorts of patients were selected from the data source using predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria that were driven by the study objectives. The study period was defined as January 1, 2009–December 31, 2013.

Cohort 1

To estimate the proportion of patients with COPD who receive a triple therapy maintenance regimen (Cohort 1), we identified patients with a COPD diagnosis during the study period (January 1, 2009–December 31, 2013). A COPD diagnosis was defined as two or more outpatient medical claims (on separate dates) or at least one inpatient medical claim; these claims must have a primary or secondary diagnosis of COPD (International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision [ICD-9] – Clinical Modification, diagnosis code of 491. xx [chronic bronchitis], 492.xx [emphysema], or 496.xx [COPD, unspecified]). Patients were also required to be at least 40 years of age at the COPD diagnosis date (date of first inpatient or second outpatient claim for COPD) and have continuous enrollment in a health plan for a period of 24 consecutive months following the COPD diagnosis date. From this COPD patient population, we selected the patients who received triple therapy during the 24-month follow-up period. These patients provided the numerator required for estimating the proportion of patients receiving triple therapy. Patients were deemed to be on triple therapy if the days supplied of all three therapy components (LABA, LAMA, and ICS, in free-dose or fixed-dose combination) overlapped for ≥30 days (eg, LAMA + LABA/ICS, LAMA + LABA + ICS, and LAMA/LABA + ICS). Further details on the identification of triple therapy are provided in the “Variables” section.

Cohort 2

We separately selected patients who initiated triple therapy during the study period as Cohort 2 (ie, Cohort 2 was not a subset of Cohort 1) to describe the characteristics of patients before they initiate a triple therapy maintenance regimen and assess the concordance of triple therapy use with GOLD guidelines. The triple therapy index date was defined as the date of initiation of the third component of triple therapy. All patients were required to have a COPD diagnosis during the study period; the COPD diagnosis was the same as that defined for Cohort 1. Patients were also required to be at least 40 years of age at the COPD diagnosis date and have continuous enrollment in a health plan for a period of 12 consecutive months before and one month after the triple therapy index date. Patients were excluded if they had received triple therapy in the 12-month period prior to the triple therapy index date.

Patients with at least one medical claim with a diagnosis of asthma (ICD-9 493.xx), cystic fibrosis (ICD-9 277.0), or lung cancer (ICD-9 162.xx, except 162.0x) during the study period were excluded from both cohorts.

Variables

Triple therapy

Medications for inclusion as components of a triple therapy maintenance regimen were identified (only those medications in the market at the time of the study were included) by the presence of at least one pharmacy claim and included LAMAs (aclidinium and tiotropium), LABAs (arformoterol, formoterol, indacaterol, olodaterol, and salmeterol), LABA + LAMA (umeclidinium + vilanterol), ICS (budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone, and mometasone furoate/ammonium lactate), and LABA + ICS (budesonide + formoterol, fluticasone + salmeterol, fluticasone + vilanterol, and mometasone furoate + formoterol fumarate). The date of the identified pharmacy claim and the days supplied associated with that claim were used to construct treatment episodes for each drug in each therapeutic class (ie, LAMA, LABA, and ICS). The days’ supply of overlapping fills was appended to the start day after the end of the previous fill’s supply. For instance, if a patient had 7 days of a drug remaining when a prescription was refilled, the days supplied of the newly refilled medication were added on to the days supplied of the prior medication. Therefore, the days supplied of two consecutive 30-day fills of the same medication totaled 60 days, whether or not one was refilled early. Triple therapy was identified when treatment with at least one prescription for an LAMA, an LABA, and an ICS (free-dose or fixed-dose combinations) overlapped for ≥30 consecutive days. The initiation date of the third triple therapy component meeting the mentioned criteria was designated as the triple therapy index date.

Baseline characteristics

Demographic variables of interest identified for Cohort 2 included age on the COPD diagnosis date, gender, and the US geographic region. Clinical characteristics included the Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCI),9 comorbidities of interest (Table S1), and COPD severity in the 12-month pre-index period.

In the absence of lung function values, it is difficult to establish GOLD grades and thus to assess the concordance of triple therapy with GOLD recommendations. Therefore, this study used two methods to assess COPD severity using a claims database.

Method 1 was based on a validated claims-based algorithm proposed by Wu et al.10 This algorithm uses clinical characteristics that can be found in administrative claims databases (eg, number of hospitalized days due to acute exacerbations of COPD, presence of oxygen therapy, etc) to determine COPD severity. Patients were classified as GOLD Grade 1, 2, 3, or 4.

Method 2 was based on frequency and severity of exacerbations (Table S2). Patients with no exacerbations, or only one mild exacerbation, were classified as GOLD Grade 1 or 2. Patients with more than one mild exacerbation, or a moderate or severe exacerbation were classified in GOLD Grade 3 or 4.

We assessed the following baseline medications for COPD (alone or in fixed-dose combinations when applicable): short-acting beta-2 agonists, short-acting muscarinic antagonists, LABAs, LAMAs, ICS, phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors, methylxanthines, and oral and injectable systemic corticosteroids. Other drugs assessed were antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections, antidiabetic medications, and cardiovascular medications (Table S3).

HRU, both all-cause and COPD-related (defined as a primary or discharge diagnosis of COPD associated with that medical claim), included inpatient, ED, outpatient visits, and inpatient length of stay. Spirometry assessment and oxygen therapy were identified using Current Procedural Terminology Version 4 and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes (Table S4).

Data analysis

Objective 1: proportion receiving triple therapy

To estimate the proportion of patients with COPD who received a triple therapy maintenance regimen, the number of patients taking triple therapy in the 24-month follow-up period after the COPD diagnosis date in Cohort 1 was divided by the number of COPD patients from Cohort 1. Additionally, the proportion of patients with COPD who received triple therapy among those who were treated with any maintenance medication was calculated in a similar manner. Instead of using the total number of patients with COPD in Cohort 1, this additional calculation used a subset of Cohort 1 patients receiving at least one prescription of LAMA, LABA, ICS, or PDE-4, or their fixed-dose combinations during the 24 months following diagnosis in the denominator.

Objective 2: characteristics and HRU

To describe patient characteristics and HRU prior to a triple therapy maintenance regimen, descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the baseline demographic and clinical variables for Cohort 2. Mean values, medians, standard deviations, and ranges were reported for continuous variables, and frequency (number and percentage) was reported for categorical variables. For HRU, the frequency and percentage of patients with inpatient, ED, and outpatient visits were reported; visits in which spirometry was measured or oxygen therapy was provided were also identified.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.4.

Results

Cohort 1

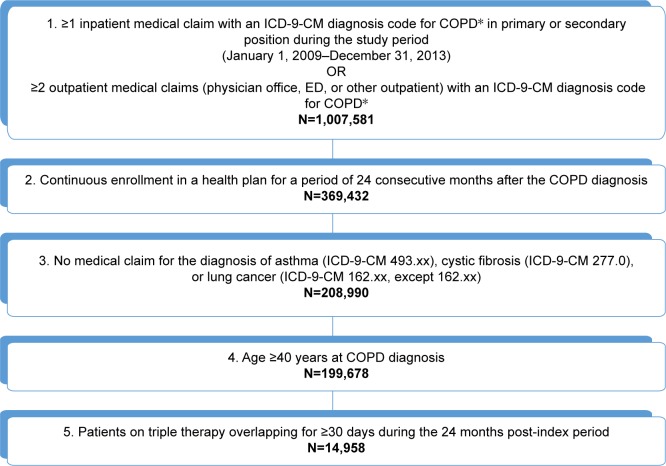

A total of 199,678 patients with COPD were selected in Cohort 1 (Figure 1); of those, 14,958 (7.5%) received triple therapy in the 24-month period after COPD diagnosis date. A total of 58,583 (29.3%) patients with COPD received at least one LAMA, LABA, ICS, or PDE-4 during the same follow-up period; 25.5% of such patients were on a triple therapy regimen. The mean age of all Cohort 1 patients at the date of COPD diagnosis was 62.4±10.6 years. Nearly all triple therapy patients (98.5%) were treated with an LAMA and a fixed-dose combination LABA/ICS medication. The majority of patients (74.8%) were treated with tiotropium bromide and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol xinafoate, while 22.0% of patients were treated with tiotropium bromide and budesonide/formoterol fumarate.

Figure 1.

Sample selection for Objective 1 (to estimate the proportion of patients with COPD who receive a triple therapy maintenance regimen [LAMA/LABA/ICS]).

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. *Defined as ICD-9-CM code for 491.xx (chronic bronchitis), 492.xx (emphysema), or 496.xx (COPD, unspecified) in primary or secondary position.

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist.

Cohort 2

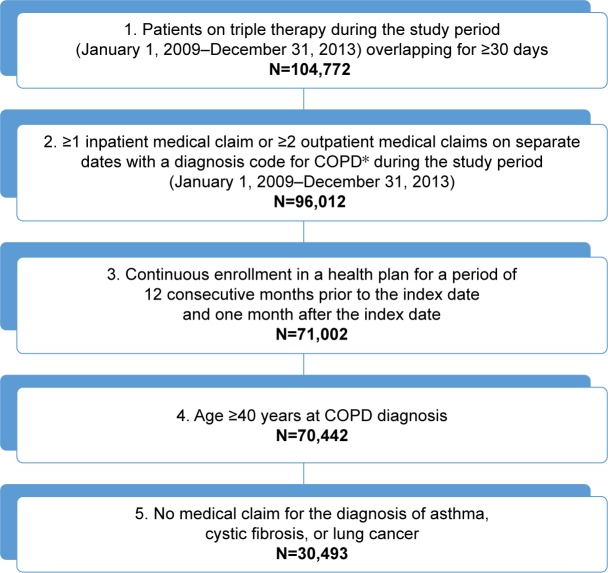

A total of 30,493 patients with COPD who were treated with triple therapy were selected for Cohort 2 (Figure 2). The mean age at the index date was 64.7±9.2 years, and over 87% of patients were 55 years of age or older (Table 1). More than half of all patients (56.9%) were male.

Figure 2.

Sample selection for Objective 2 (to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics, and health care resource use of patients with COPD prior to initiation of a triple therapy maintenance regimen [LAMA/LABA/ICS]).

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. *Defined as ICD-9-CM code for 491.xx (chronic bronchitis), 492.xx (emphysema), or 496.xx (COPD, unspecified) in primary or secondary position.

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of COPD patients on triple therapy from Cohort 2 at the index date

| Baseline demographic characteristics | COPD patients on triple therapy, N=30,493 |

|---|---|

| Age at index, years | |

| Mean (SD); median (range) | 64.7 (9.2); 64.0 (40–84) |

| Age group at index, years | |

| 40–54 | 3,777 (12.4%) |

| 55–64 | 13,063 (42.8%) |

| 65 and above | 13,653 (44.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 17,351 (56.9%) |

| Female | 13,142 (43.1%) |

| Geographic region | |

| Midwest | 10,405 (34.1%) |

| South | 8,903 (29.2%) |

| West | 2,660 (8.7%) |

| East | 8,525 (28.0%) |

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. Population used is the one identified for Objective 2.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Clinical characteristics of Cohort 2 (Table 2) were determined for the year prior to the initiation of triple therapy. The mean DCI was 1.4±1.9, and nearly two-thirds (61.7%) of patients had a diagnosis of heart failure, 52.9% had a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia, and 27.5% had a diagnosis of depression.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of COPD patients on triple therapy from Cohort 2 in the baseline year

| Baseline clinical characteristics | COPD patients on triple therapy, N=30,493 |

|---|---|

| DCI | |

| Mean (SD); median (range) | 1.4 (1.9); 1.0 (0–20) |

| DCI, category | |

| 0 | 13,350 (43.8%) |

| 1 | 6,582 (21.6%) |

| 2 | 4,355 (14.3%) |

| 3 | 2,535 (8.3%) |

| 4+ | 3,671 (12.0%) |

| Baseline comorbidities | |

| Heart failure | 18,804 (61.7%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia | 16,116 (52.9%) |

| Depression | 8,372 (27.5%) |

| Stroke | 6,643 (21.8%) |

| Mood disorders | 5,872 (19.3%) |

| Hypertension | 5,881 (19.3%) |

| TIA | 4,946 (16.2%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4,299 (14.1%) |

| Cancer | 3,543 (11.6%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3,343 (11.0%) |

| Respiratory failure | 3,131 (10.3%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 2,489 (8.2%) |

| Insomnia | 2,400 (7.9%) |

| Pneumonia | 1,898 (6.2%) |

| Osteoporosis | 1,549 (5.1%) |

| Anxiety | 1,421 (4.7%) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 643 (2.1%) |

| COPD severity (based on algorithm from Wu et al10) | |

| GOLD 1, mild | 10,511 (34.5%) |

| GOLD 2, moderate | 12,433 (40.8%) |

| GOLD 3, severe | 6,862 (22.5%) |

| GOLD 4, very severe | 687 (2.3%) |

| COPD severity (based on frequency and severity of exacerbations) | |

| GOLD 1 or 2 | 18,483 (60.6%) |

| None | 17,448 (57.2%) |

| Mild (only one exacerbation) | 1,035 (3.4%) |

| GOLD 3 or 4 | 12,010 (39.4%) |

| Mild (more than one exacerbation) | 5,468 (17.9%) |

| Moderate | 4,401 (14.4%) |

| Severe | 2,141 (7.0%) |

| Baseline medications | |

| Antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections | 16,469 (54.0%) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 14,679 (48.1%) |

| COPD medications | 21,696 (71.2%) |

| LAMA | 20,889 (68.5%) |

| LABA | 650 (2.1%) |

| ICS | 728 (2.4%) |

| LAMA + LABA | 0 (0.0%) |

| LABA + ICS | 20,178 (66.2%) |

| SABA | 19,528 (64.0%) |

| SAMA | 1,373 (4.5%) |

| SABA + SAMA | 4,963 (16.3%) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 15,008 (49.2%) |

| PDE-4 | 238 (0.8%) |

| Methylxanthines | 1,184 (3.9%) |

| Antidiabetic medications | 4,897 (16.1%) |

| Cardiovascular medications | 18,350 (60.2%) |

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. Population used is the one identified for Objective 2.

Abbreviations: DCI, Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist; PDE-4, phosphodiesterase-4; SABA, short-acting beta-2 agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Using the algorithm by Wu et al to classify this sample, 34.5% had mild COPD (GOLD 1), 40.8% had moderate COPD (GOLD 2), 22.5% had severe COPD (GOLD 3), and 2.3% had very severe COPD (GOLD 4). Over half (57.2%) of patients did not have any exacerbations, while 3.4% had one mild exacerbation, 17.9% had two mild exacerbations, 14.4% had a moderate exacerbation, and 7.0% had a severe exacerbation. When we classified COPD severity based on exacerbation frequency and severity, we assessed 18,483 (60.6%) patients as GOLD Grade 1 or 2, and 12,010 (39.4%) patients as GOLD Grade 3 or 4 (Table 2). During the 12-month pre-index period, 47.0% of patients had spirometry conducted, and 29.8% of patients had oxygen therapy during a medical visit. The top five medications used were COPD medications (71.2%), cardiovascular medications (60.2%), antibiotics commonly prescribed for respiratory infections (54.0%), oral corticosteroids (48.1%), and antidiabetic medications (16.1%).

All-cause health care utilization for Cohort 2 in the year prior to the index date is presented in Table 3. Over one-third (34.9%) of patients had at least one hospitalization during this period, and those patients had a mean number of 1.8±2.1 hospitalizations. The average length of stay among patients with at least one hospitalization was 9.9±13.2 days. Almost all patients (98.0%) had at least one outpatient visit, with a mean of 19.5±18.5 visits per patient. Over one-third (34.8%) of patients had an ED visit during the year prior to the index date, with a mean of 0.7±2.0 visits.

Table 3.

All-cause HRU among COPD patients on triple therapy from Cohort 2 in the baseline year

| All-cause HRU | COPD patients on triple therapy, N=30,493 |

|---|---|

| Hospitalization | |

| At least one hospitalization | 10,655 (34.9%) |

| Among patients with at least one hospitalization | |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of hospitalizations | 1.8 (2.1); 1.0 (1–117) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of length of stay per patient | 9.9 (13.2); 6.0 (1–196) |

| Outpatient visits | |

| Any outpatient visit | 29,895 (98.0%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of outpatient visits per patient | 19.5 (18.5); 14.0 (0–347) |

| ED visits | |

| Any ED visit | 10,625 (34.8%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of ED visits per patient | 0.7 (2.0); 0.0 (0–140) |

| Spirometry visits | |

| Any visit where spirometry was assessed | 14,318 (47.0%) |

| Among those with either no exacerbation or one mild exacerbation | 8,078/18,483 (43.7%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of visits in which spirometry was assessed | 0.9 (1.4); 0.0 (0–38) |

| Oxygen therapy | |

| Any visit with oxygen therapy | 9,099 (29.8%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of visits with oxygen therapy | 4.3 (9.0); 0.0 (0–347) |

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. Population used is the one identified for Objective 2. All-cause visits were defined as any inpatient or outpatient visit related to any diagnosis; COPD-related visits were identified as inpatient or outpatient visits in which a diagnosis code for COPD is the primary diagnosis code associated with that visit (or discharge claim for an inpatient visit). Inpatient and ED visits were limited to one per day; outpatient visits were limited to one per provider per day; length of stay was truncated for stays over 365 days; COPD exacerbation severity was evaluated regardless of cause by definition of the algorithm. Mean, SD, median, and range were reported for the entire population.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HRU, health care resource utilization; SD, standard deviation.

Table 4 presents COPD-related resource utilization among patients in Cohort 2. Of all patients in this cohort, 18.2% had at least one COPD-related hospitalization in the year prior to the index date; among those who had a hospitalization, the mean number of COPD-related hospitalizations was 1.5±1.2, with a mean length of stay of 5.1±5.0 days. Over three-quarters of patients (75.7%) had at least one outpatient visit for COPD, with a mean of 2.9 (±4.3) visits. ED visits were less frequent, and 7.0% of patients had a COPD-related ED visit.

Table 4.

COPD-related HRU among COPD patients on triple therapy from Cohort 2 in the baseline year

| COPD-related HRU | COPD patients on triple therapy, N=30,493 |

|---|---|

| Hospitalization | |

| Any hospitalization | 5,555 (18.2%) |

| Among patients with at least one hospitalization | |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of hospitalizations | 1.5 (1.2); 1 (1–33) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) length of stay per patient | 5.1 (5.0); 4 (1–62) |

| Outpatient visits | |

| Any outpatient visit | 23,084 (75.7%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of outpatient visits per patient | 2.9 (4.3); 2 (0–149) |

| ED visits | |

| Any ED visit | 2,132 (7.0%) |

| Mean (SD); median (range) of ED visits per patient | 0.1 (0.4); 0 (0–12) |

Notes: IMS PharMetrics Plus database from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013. Population used is the one identified for Objective 2. All-cause visits were defined as any inpatient or outpatient visit related to any diagnosis; COPD-related visits were identified as inpatient or outpatient visits in which a diagnosis code for COPD is the primary diagnosis code associated with that visit (or discharge claim for an inpatient visit). Inpatient and ED visits were limited to one per day; outpatient visits were limited to one per provider per day; length of stay was truncated for stays over 365 days; COPD exacerbation severity was evaluated regardless of cause by definition of the algorithm. Mean, SD, median, and range were reported for the entire population.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HRU, health care resource utilization; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study of a large US claims database, the proportion of patients receiving any maintenance medication was 29.3%, consistent with previous research indicating that only 29%–45% of diagnosed COPD patients are treated with maintenance drugs.8,11 Among this subset of treated patients, 25.5% of patients received triple therapy. Out of all the patients with a COPD diagnosis, 7.5% of patients were treated with triple therapy.

The mean age of the patients receiving triple therapy was relatively high (approximately 65 years) as expected,12 and over half of the patients were male. Comorbidities associated with aging were relatively common, including heart failure, hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia, depression, stroke, and hypertension. Overall health care utilization was also high in this sample; over one-third of patients had at least one hospitalization and/or one ED visit in the year before triple therapy, while the majority of patients had an outpatient visit. However, this was partially driven by the selection criteria used to identify this sample, as at least one inpatient visit or two outpatient visits with a diagnosis of COPD were required during the study period.

GOLD specifically recommends triple therapy for only the group of patients with severe or very severe airflow limitation (GOLD Grade 3 or 4) who are highly symptomatic, and experiencing two or more exacerbations, or at least one exacerbation leading to a hospitalization per year. This study found that among all COPD patients who received triple therapy, approximately 75% had either mild or moderate COPD (GOLD Grade 1 or 2, assessed using the Wu et al claims-based algorithm), indicating that a large percentage of patients may be receiving triple therapy contrary to treatment recommendations. Additionally, when we used exacerbation severity and frequency as a proxy for GOLD staging, our findings that 60.4% of patients might have been GOLD Grade 1 or 2, and that over half of all patients had no spirometry performed (consequently providing no assessment of a patient’s severity of airflow obstruction to establish GOLD Grade), further support the possibility that a substantial percentage of patients with COPD may be receiving overtreatment with triple therapy.

The management of stable COPD focuses on reducing symptoms and reducing future risk of disease progression, exacerbations, and mortality.3 It is possible that, for those receiving triple therapy, the clinician’s assessment of the patient’s COPD status warranted further treatment. However, in this group of patients with mild or no exacerbations (consistent with GOLD Grade 1 or 2), the evidence to support the use of triple therapy (inclusive of an ICS) versus LABA or LAMA monotherapy and/or LABA/LAMA combination therapy may not be intuitive based on the history available for the 12 months prior to treatment.

The point of consideration being raised by this manuscript is the need to assess 1) whether one should add a third treatment, versus a dual therapy, when the patient clinically needs a change, or 2) whether one should continue the use of triple therapy when no exacerbations have occurred in the prior year. Receiving ICS also places patients at an increased risk of pneumonia and other comorbid diseases, ultimately adding to the disease burden of COPD patients.13 It is recognized that the choice of therapy can be affected by factors outside of pure clinical assessment, such as limiting the number of prescription changes affecting the patient (ie, adding a new medicine to an existing regimen versus a complete regimen change), clinician confidence/experience with treatment options (LABA/ICS versus LABA/LAMA), or patients misunderstanding of their regimen where they continue to use a medication that the physician has discontinued. Regardless, the use of triple therapy should be assessed based on the available evidence, and alternatives should be considered when appropriate.

This study has limitations consistent with those of other retrospective claims database studies. Claims diagnoses represent justifications for billing and may not always accurately reflect patients’ medical conditions. Further, a pharmacy claim indicates the availability of a medication to a patient, not actual use of that medication. Health care received outside the health insurance plan, such as over-the-counter medications, does not appear in the claims data. Also, the geographic distribution of the overall sample was not necessarily representative of the population of the US. Finally, the requirement of continuous enrollment in a health plan might introduce selection bias to the study design; patients without a continuous plan enrollment history may have less access to medical care and therefore may have different comorbidity profiles and treatment patterns than patients included in the study.

Absence of spirometry results is a potential limitation for this study, as COPD severity cannot be conclusively ascertained without spirometry results. To mitigate this limitation, a validated algorithm by Wu et al was used to identify COPD severity for patients included in these analyses.10 This algorithm was found to have good external and construct validity, and uses clinical characteristics that are found in administrative claims databases to classify COPD severity. Both the severity (via treatment setting) and frequency of exacerbations were also assessed as a supplemental indicator of COPD severity.

Spirometry may be underreported in claims data, as patients could have been tested at sites other than their physician’s office.13 However, the percentage of patients with evidence of spirometry in this study was similar to that seen in other studies.14 Additionally, some measurements that are potentially associated with disease severity and control,15,16 such as smoking status or history, alcohol consumption, socioeconomic status, body mass index, health-related quality of life, literacy, and access to care, were not available for this analysis of administrative claims data. Although HRU during the year prior to triple therapy initiation was identified, a future study might compare the costs and utilization after treatment to those of patients who have similar disease severity, but are not treated with triple therapy. Finally, triple therapy users could be compared to a matched cohort of patients who did not start triple therapy; factors associated with triple therapy initiation could then be identified.

Conclusion

This large US claims database study found that among COPD patients treated with maintenance medications, one-quarter were treated with triple therapy. Even though triple therapy is recommended for only the most severe COPD patients, this study indicates that a substantial percentage of patients receiving triple therapy are likely GOLD Grade 1 or 2, and that over half of patients did not receive the spirometric testing required to assess airflow limitation, a valuable component of disease severity assessment. Any potential overprescribing of triple therapy may lead to unnecessary costs both to the patient and to the health care system. Careful assessment needs to be conducted by prescribers so that patients with COPD are prescribed triple therapy only when necessary and in concordance with treatment recommendations.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

Diagnosis codes used for disease conditions of interest

| Diagnosis | ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 300.0x, 300.2x |

| Cancer | 140.xx–208.xx |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 427.x |

| Depression | 296.2x, 296.3x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 301.13x, 308.0x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.xx |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250.xx |

| Heart failure | 428.xx |

| Hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia | 272.0x–272.4x |

| Hypertension | 401.xx–405.xx |

| Insomnia | 307.42, 307.41, 327.0, 780.51, 780.52 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 410.xx–414.xx |

| Mood disorders | 296.xx |

| Myocardial infarction | 410.xx, 412.xx |

| Osteoporosis | 733.0x |

| Pneumonia | 480.xx–486.xx, 770.0x, 997.31 |

| Respiratory failure | 518.81, 518.83, or 518.84 |

| Stroke | 430.xx–434.xx |

| TIA | 435.xx |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table S2.

Definitions of COPD exacerbations by severity

| Type of COPD exacerbations | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mild COPD exacerbation | An ED visit OR office visit OR outpatient non-ED visit with: 1) any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD; OR 2) a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position; OR 3) a diagnosis for respiratory failure in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD (no hospitalization); AND 4) a pharmacy claim for any of the antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections within seven days of the visit; OR 5) a prescription claim for an oral corticosteroid within seven days of the visit |

| Moderate COPD exacerbation | A hospitalization with: 1) a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD AND any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position; OR 2) a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position; AND 3) no respiratory failure |

| Severe COPD exacerbation | 1) A hospitalization with any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position; AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for respiratory failure; OR 2) a hospitalization with a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for respiratory failure; OR 3) a hospitalization with a principal diagnosis for respiratory failure AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification.

Table S3.

List of non-COPD medications used in patients diagnosed with COPD

| Type of medications | Drug classes |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections | Amino-penicillins |

| First-generation cephalosporins | |

| Second-generation cephalosporins | |

| Macrolides | |

| Penicillins | |

| Tetracyclines | |

| Antidiabetic medications | Oral antidiabetic drugs |

| Biguanides | |

| Sulfonylureas | |

| Meglitinides | |

| Thiazolidinediones | |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors | |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors | |

| Other antidiabetic drugs | |

| Insulin | |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibitors | |

| Cardiovascular medications | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers (or inhibitors) | |

| Beta blockers | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Diuretics | |

| Digitalis preparations | |

| Vasodilators |

Table S4.

Procedure codes used to identify procedures of interest

| Procedure | CPT codes | HCPCS codes |

|---|---|---|

| Spirometry | 94010, 94014–94016, 94060, 94070, 94375, 94620 | |

| Oxygen therapy | E0424, E0425, E0430, E0431, E0433, E0434, E0435, E0439, E0440, E0441, E0442, E0443, E0444, E1390, E1391, E1392, E1405, E1406, K0738, K0741, S8120, S8121 |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Samuel Huse of Evidera for his programming assistance during the conduct of this study and Janet Dooley of Evidera for her assistance with the editing and production of this paper.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc. provided the funding for this study. RL and SK are salaried employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. JCS, TDB, JL, and TKW are currently employees of Evidera, which provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, and other organizations. In their salaried positions, they work with a variety of companies and organizations and are precluded from receiving payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. Evidera received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim for work on the project and the manuscript. XP was an employee of Evidera during the conduct of this study and the writing of this manuscript; she is currently employed by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Marlborough, MA. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance − United States, 1971–2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(6):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2016 Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2016. [Accessed April 27, 2016]. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd-2016/

- 4.Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health (CADTH) Triple therapy for moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CADTH Technol Overv. 2010;1(4):e0129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iannella H, Luna C, Waterer G. Inhaled corticosteroids and the increased risk of pneumonia: what’s new? A 2015 updated review. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(3):235–255. doi: 10.1177/1753465816630208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asche CV, Leader S, Plauschinat C, et al. Adherence to current guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among patients treated with combination of long-acting bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:201–209. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S25805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannino DM, Tzy-Chyi Yu M, Zhou H, Higuchi K. Effects of GOLD-adherent prescribing on COPD symptom burden, exacerbations, and health care utilization in a real-world setting. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami) 2015;2(3):223–235. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2.3.2014.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Make B, Dutro MP, Paulose-Ram R, Marton JP, Mapel DW. Under-treatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S27032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Cifaldi M, Kang Y, Mallet D, Colice G. Development of a COPD severity score. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1679–1687. doi: 10.1185/030079906X115621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diette GB, Dalal AA, D’Souza AO, Lunacsek OE, Nagar SP. Treatment patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in employed adults in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:415–422. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S75034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busch R, Han MK, Bowler RP, et al. COPDGene Investigators Risk factors for COPD exacerbations in inhaled medication users: the COPDGene study biannual longitudinal follow-up prospective cohort. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:28. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoh RJ, Fero LJ, Shapiro H, et al. Performance of a new screening spirometer at a community health fair. Respir Care. 2002;47(10):1150–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins NM, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, Chalmers GW, Dunn FG, McMurray JJ. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnostic pitfalls and epidemiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(2):130–139. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahadori K, FitzGerald JM. Risk factors of hospitalization and readmission of patients with COPD exacerbation − systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(3):241–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omachi TA, Sarkar U, Yelin EH, Blanc PD, Katz PP. Lower health literacy is associated with poorer health status and outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):74–81. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2177-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Diagnosis codes used for disease conditions of interest

| Diagnosis | ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 300.0x, 300.2x |

| Cancer | 140.xx–208.xx |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 427.x |

| Depression | 296.2x, 296.3x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 301.13x, 308.0x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.xx |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250.xx |

| Heart failure | 428.xx |

| Hypercholesterolemia/hyperlipidemia | 272.0x–272.4x |

| Hypertension | 401.xx–405.xx |

| Insomnia | 307.42, 307.41, 327.0, 780.51, 780.52 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 410.xx–414.xx |

| Mood disorders | 296.xx |

| Myocardial infarction | 410.xx, 412.xx |

| Osteoporosis | 733.0x |

| Pneumonia | 480.xx–486.xx, 770.0x, 997.31 |

| Respiratory failure | 518.81, 518.83, or 518.84 |

| Stroke | 430.xx–434.xx |

| TIA | 435.xx |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table S2.

Definitions of COPD exacerbations by severity

| Type of COPD exacerbations | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mild COPD exacerbation | An ED visit OR office visit OR outpatient non-ED visit with: 1) any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD; OR 2) a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position; OR 3) a diagnosis for respiratory failure in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD (no hospitalization); AND 4) a pharmacy claim for any of the antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections within seven days of the visit; OR 5) a prescription claim for an oral corticosteroid within seven days of the visit |

| Moderate COPD exacerbation | A hospitalization with: 1) a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD AND any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position; OR 2) a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position; AND 3) no respiratory failure |

| Severe COPD exacerbation | 1) A hospitalization with any of the diagnosis codes indicative of an acute exacerbation in the primary position; AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for respiratory failure; OR 2) a hospitalization with a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for respiratory failure; OR 3) a hospitalization with a principal diagnosis for respiratory failure AND a secondary ICD-9-CM code for COPD |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision – Clinical Modification.

Table S3.

List of non-COPD medications used in patients diagnosed with COPD

| Type of medications | Drug classes |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics commonly used for respiratory infections | Amino-penicillins |

| First-generation cephalosporins | |

| Second-generation cephalosporins | |

| Macrolides | |

| Penicillins | |

| Tetracyclines | |

| Antidiabetic medications | Oral antidiabetic drugs |

| Biguanides | |

| Sulfonylureas | |

| Meglitinides | |

| Thiazolidinediones | |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors | |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors | |

| Other antidiabetic drugs | |

| Insulin | |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibitors | |

| Cardiovascular medications | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers (or inhibitors) | |

| Beta blockers | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Diuretics | |

| Digitalis preparations | |

| Vasodilators |

Table S4.

Procedure codes used to identify procedures of interest

| Procedure | CPT codes | HCPCS codes |

|---|---|---|

| Spirometry | 94010, 94014–94016, 94060, 94070, 94375, 94620 | |

| Oxygen therapy | E0424, E0425, E0430, E0431, E0433, E0434, E0435, E0439, E0440, E0441, E0442, E0443, E0444, E1390, E1391, E1392, E1405, E1406, K0738, K0741, S8120, S8121 |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System.