Abstract

Curcumin (Cur) is a promising photosensitizer that could be used in photodynamic therapy. However, its poor solubility and hydrolytic instability limit its clinical use. The aim of the present study was to encapsulate Cur into solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) in order to improve its therapeutic activity. The Cur-loaded SLNs (Cur-SLNs) were prepared using an emulsification and low-temperature solidification method. The functions of Cur and Cur-SLNs were studied on the non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells for photodynamic therapy. The results revealed that Cur-SLNs induced ~2.27-fold toxicity higher than free Cur at a low concentration of 15 μM under light excitation, stocking more cell cycle at G2/M phase. Cur-SLNs could act as an efficient drug delivery system to increase the intracellular concentration of Cur and its accumulation in mitochondria; meanwhile, the hydrolytic stability of free Cur could be improved. Furthermore, Cur-SLNs exposed to 430 nm light could produce more reactive oxygen species to induce the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential. Western blot analysis revealed that Cur-SLNs increased the expression of caspase-3, caspase-9 proteins and promoted the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2. Overall, the results from these studies demonstrated that the SLNs could enhance the phototoxic effects of Cur.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, curcumin, solid lipid nanoparticles, drug delivery, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a minimally invasive technique that shows negligible drug resistance, remarkable selectivity, high controllability, and low systemic toxicity when compared with traditional chemotherapies and radiotherapies.1–3 PDT involves three key components: light exposure, photosensitizer, and oxygen. When a photosensitizer is exposed to light of an appropriate wavelength, the excited photosensitizer transfers energy to oxygen, generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), and damages cancer cells.4,5 Undoubtedly, the discovery and optimization of photosensitizer are essential to the development of PDT.

Curcumin (Cur), a polyphenol extracted from the turmeric root, has been shown to exhibit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities.6–8 The photocytotoxic effects of Cur have been recently discovered.9–19 However, the extremely low aqueous solubility and hydrolytic instability under physiological conditions limit its uses.20–22 Many nanoparticles have been used to improve its stability, aqueous solubility, and bioavailability, such as layered double hydroxides, poly(lactide-co-glycolide), chitosan, cellulose, nanogel, and cyclodextrin.8,23–26

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) synthesized with different types of physiological lipids have attracted increasing attention as a novel drug carrier because of their potential advantages, including good biocompatibility, protection for the incorporated compound against degradation, and less toxicity.27–31

In this study, we aimed to improve the photocytotoxicity of Cur by SLNs for cancer treatment. Cur-SLNs were successfully synthesized using emulsification and low-temperature solidification methods and characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses, zeta potential detection, and photon correlation spectroscopy. The results showed that in A549 cells, in comparison with Cur, Cur-SLNs could largely induce tumor cell apoptosis and further arrest cell cycle. Confocal microscopy imaging clearly visualized that the delivery of Cur-SLNs to A549 cells was better than that of free Cur. In order to explore the molecular mechanism by which the SLNs can improve the PDT effects of Cur, we investigated the protein expression of Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3, and caspase-9 through Western blot analysis. Altogether, our data showed the promise of potential applications of delivering Cur as SLNs for PDT.

Materials and methods

Materials

Polyoxyethylene(40)stearate (Myrj52), stearic acid, chloroform, lecithin, Tween-80, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6- indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). Cur (≥98%) was purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). β-Actin, caspase-3, caspase-9, Bax, and Bcl-2 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. Nucleoprotein and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit, bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent, Annexin V-APC/7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) apoptosis detection kit, cell cycle detection kit, 3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) apoptosis detection kit, and ROS detection kit were purchased from KeyGEN Biotech (Nanjin, People’s Republic of China). Dimethyl sulfoxide was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA), and MitoTracker-Red was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Water was prepared using a Millipore Milli-Q® system (Bedford, MA, USA) and decarbonated by boiling. Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640, penicillin–streptomycin, fetal calf serum, and trypsinase were purchased from Gibco (BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA).

Preparation of Cur-SLNs

Cur-SLNs were prepared using emulsification and low-temperature solidification methods.8,28,29 The organic phase containing 0.1 g lecithin, 0.15 g Cur, and 0.2 g stearic acid was dissolved in 10 mL of chloroform. Also, 0.2 g of Myrj52 dissolved in 30 mL of deionized water formed the aqueous phase. After complete dissolution of the aqueous phase at 75°C, the organic phase was injected into it and stirred at 1,200 rpm until the organic solvent disappeared. Then the system was quickly moved to an ice-cold environment at 0°C–2°C, added to 10 mL of cold water, and stirred at 1,200 rpm for 2 h. Centrifugal separation was applied to remove the supernatant at 20,000 rpm (Avanti J25 centrifuge, JA 25.50 rotor, Beckman Coulter). The precipitate was washed by deionized water twice. Finally, the precipitate was resuspended in ultrapure water, refrigerated at −80°C overnight, and lyophilized in a tabletop lyophilizer. The blank carriers (SLNs) were prepared using the same procedure without the addition of Cur.

TEM, particle size, and zeta potential measurements

A drop of a diluted suspension of Cur-SLNs was placed on a carbon-coated copper TEM grid to form a thin liquid film, negatively stained with 2% (w/v) sodium phosphotungstate for 10 min and allowed to air-dry, and examined with a transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The particle size and the zeta potential of Cur-SLNs were measured using a Malvern Zeta-sizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The experiments were repeated three times.

Quantifying the loading efficiency of Cur

The amount of loaded Cur in Cur-SLNs was determined by ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy at 430 nm. Cur-SLNs were diluted with ethanol to the range covered within the standard curve. The concentration of Cur was calculated according to a previously obtained calibration curve for Cur (Absorption =0.1517c+0.022, r2=0.999). The experiments were repeated three times. The drug loading capacity was calculated as follows:

Cell culture and cellular uptake studies

A549 cells obtained from Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China, were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 Thermo cell incubator, with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL).

A549 cells were seeded in glass-bottom dishes and then treated with 15 μM free Cur or Cur-SLNs. After 1, 2, and 4 h of incubation, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) to remove excess free Cur or Cur-SLNs. Fresh RPMI-1640 medium was added to the dishes and the cells were observed under confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). The experiments were repeated three times.

Detection of ROS

A549 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 37°C for 16–24 h. After incubation with free Cur and Cur-SLNs (15 μM of free Cur equivalent) for 4 h, the cells were washed with PBS buffer to remove excess Cur and Cur-SLNs outside the cells. Each well was exposed to a 430 nm light-emitting diode (LED; power density 50 mW/cm2) for 20 min at the same distance to supply the same power. After incubation for 12 h, the cells were washed and harvested. Then, 150 μL of 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate was added to the cell suspension and incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Exactly 20,000 cells were analyzed using flow cytometry analysis with analytical flow cytometry instrument (BD FACSVerse).32,33 The experiments were repeated three times.

Cytotoxicity assay

MTT assay was used to assess the metabolic activity of A549 cancer cells.32 Briefly, A549 cells were seeded into 96-well plates. After 16–24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with various concentrations of free Cur, Cur-SLNs, and SLNs for 4 h. Then, the cells were washed with fresh media twice and exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min. After incubation for 12 h in the dark, the cells were incubated with 20 μL MTT (5 mg/mL) for 4 h at 37°C, followed by treatment with 150 μL dimethyl sulfoxide to dissolve the crystals. The absorbance was quantified at 492 nm using Elx 800 Universal Microplate Reader (BIO-TEK, Inc.). The errors were calculated from three independent set of experiments, each of which was performed in triplicate.

Trypan blue assay

A549 cells were seeded in 35 mm culture dishes and treated with 15 μM Cur-SLNs or free Cur. After incubation for 4 h, the cells were washed with PBS twice and exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min. Following incubation in the dark for 12 h, the cells were stained with 0.04% Trypan blue solution for 5 min. Then, the A549 cells were observed using a Leica microscope.34 The experiments were repeated three times.

Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

A549 cells were seeded into six-well plates and treated with 15 μM Cur-SLNs or free Cur for 4 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS buffer and exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min. After incubation in the dark for 12 h, the cells were harvested and stained with 2 μM JC-1 dye in 500 μL PBS for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity of each sample was detected by FACSCalibur. The experiments were repeated three times.

Apoptosis analysis

A549 cells were seeded in six-well plates for 16–24 h and incubated with 15 μM free Cur and Cur-SLNs for 4 h. They were then washed with PBS buffer twice and exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min. After incubation for 12 h, the cells were collected and fixed in 500 μL of Annexin V binding buffer containing 5 μL Annexin V-APC and 5 μL 7-AAD. After incubation at room temperature for 20 min in the dark, 20,000 cells were analyzed using fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. The experiments were repeated three times.

Cell cycle

A549 cells were seeded in six-well plates for 16–24 h and treated with Cur and Cur-SLNs (15 μM of free Cur equivalent) for 4 h. They were then exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min. After 12 h, the trypsinized cells were suspended in chilled 70% ethanol which contained 50 μg/mL propidium iodide and 100 μg/mL RNase A. After staining for 30 min, 20,000 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The experiments were repeated three times.

Western blot analysis

A549 cells were treated with Cur and Cur-SLNs (15 μM of free Cur equivalent) and exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min, and then incubated for 12 h in the dark. The cells were collected for protein extraction. Twenty microgram protein samples were denatured by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gelelectrophoresis, then separated by gel electrophoresis, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking by 5% bovine serum albumin, the primary antibodies β-actin, Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase-3, caspase-9 (1:1,000 dilution), and a secondary antibody were used to probe the protein levels. The signal was visualized with a chemiluminescent electrochemiluminescent detection system. The experiments were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. All values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Preparation and characterization of Cur-SLNs

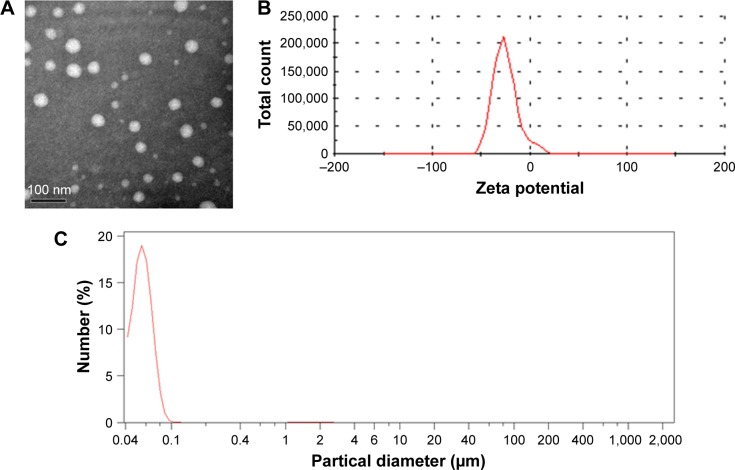

Cur-loaded SLNs were prepared using emulsification and low-temperature solidification methods following our previously reported procedures.8,28,29 TEM images (Figure 1A) revealed a discrete spherical outline, which was in accordance with photon correlation spectroscopy. The zeta potential (Figure 1B) of the SLNs was −26.2±1.3 mV, which is sufficiently high to cause the Cur-SLNs to repel each other, thereby avoiding particle aggregation and encouraging long-term stability.35 As shown in Figure 1C, the average diameter of the Cur-SLNs particles was 56.2 nm. To confirm the encapsulation and formulation of the Cur loaded in SLNs, the photophysical properties of Cur were examined. Free Cur has a distinctly high absorbance peak at 430 nm when dissolved in an ethanolic solution. The drug loading capacity was calculated as 37%±2.5%.

Figure 1.

Characterization of Cur-SLNs.

Notes: Transmission electron microscopy image (A), zeta potential distribution (B), and particle size distribution (C) of Cur-SLNs.

Abbreviation: Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles.

Cell viability assay

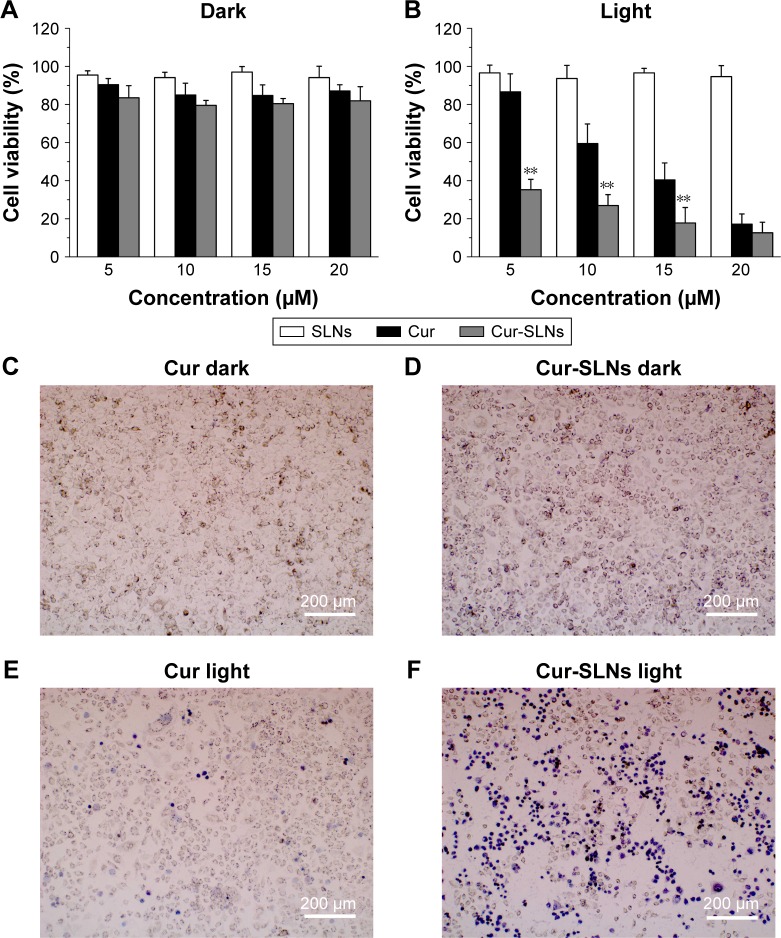

As shown in Figure 2, without light exposure, Cur-SLNs and free Cur exhibited negligible cytotoxicity to A549 cells. After having been exposed, on treatment with 10 μM free Cur and Cur-SLNs, the viability of A549 cells was found to be 67% and 27%, respectively. When A549 cells treated with 15 μM free Cur and Cur-SLNs, the viability was 40% and 18%, respectively. As expected, SLNs displayed no cytotoxicity to A549 cells either in the dark or under light exposure. Microscopic images of trypan blue stained cells further confirmed the improved PDT efficiency of Cur-SLNs over free Cur.

Figure 2.

Killing of in vitro photodynamic cancer cells.

Notes: Cell viabilities of the A549 cells treated with Cur, SLNs, Cur-SLNs in the dark (A), and with light irradiation (B). Trypan blue stained images of A549 cells (C–F) incubated with Cur or Cur-SLNs with and without laser irradiation. The statistical significances in Cur and Cur-SLNs groups were determined using a two-sample Student’s t-test. The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three experiments, **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles.

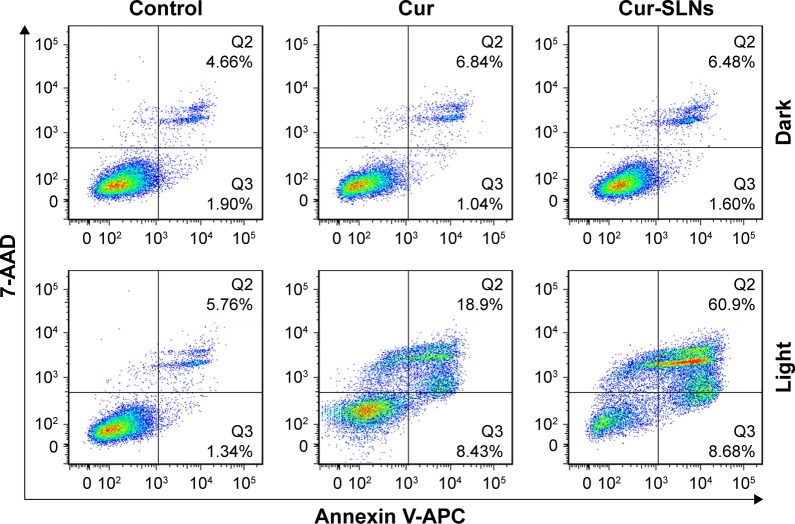

Apoptosis analysis by Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD staining

Annexin V-APC/7-AAD staining, a more sensitive method for detecting apoptosis,36 was used to determine whether Cur-SLNs demonstrated superior anticancer effects compared to free Cur. After the A549 cells were exposed to 430 nm LED for 20 min, as shown in Figure 3, 27.33% of apoptotic cells (early apoptosis plus late apoptosis) were found in the sample incubated with Cur only. When treated with Cur-SLNs (15 μM), 69.58% of apoptotic A549 cells were induced to apoptosis. In conclusion, Cur-SLNs displayed a stronger anticancer effect in A549 cells, compared to free Cur.

Figure 3.

FACS profiles of Annexin V-APC/7-AAD staining of A549 cells undergoing apoptosis induced by Cur and Cur-SLNs in the dark or with irradiation.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

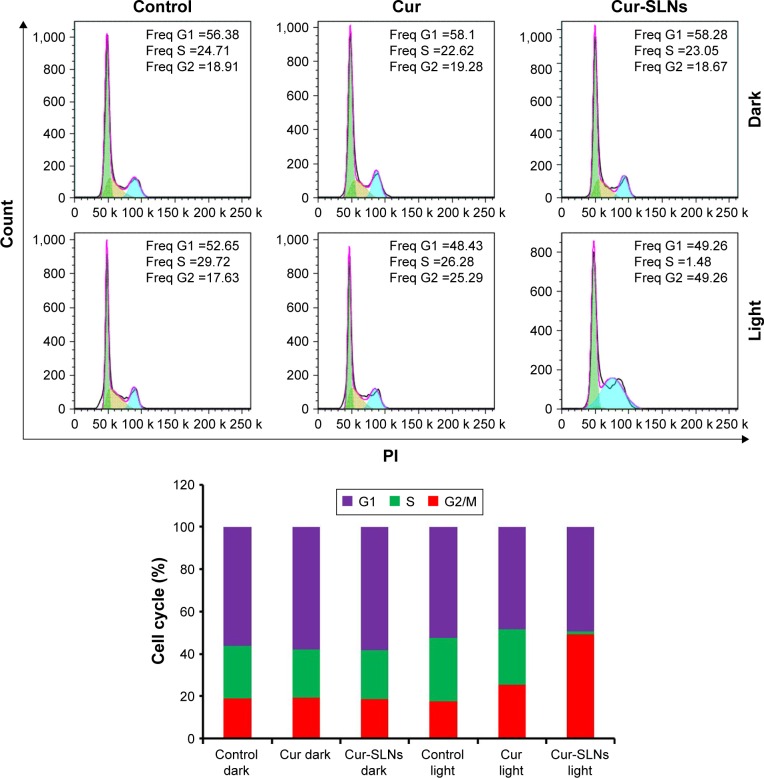

Cell cycle studies

The DNA content of cells was measured with propidium iodide.37 As shown in Figure 4, treating A549 cells with Cur and Cur-SLNs in the dark did not alter the cell cycle, compared with the untreated control group. In contrast, after they were exposed to the excitation light at 430 nm, A549 cells treated with Cur-SLNs showed 49.26% arrest in G2/M phase of cell cycle leading to cell death and the cells treated with Cur showed 25.29% arrest in G2/M phase. These data suggest that Cur-SLNs showed more significant cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase in A549 cells at the same concentration after exposure.

Figure 4.

Cell cycle analysis of A549 cells treated with Cur and Cur-SLNs in the dark or with irradiation, and bar diagrammatic representation showing the percentage cell distribution in different phases of cell cycle.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; Freq, Frequency; PI, propidium iodide.

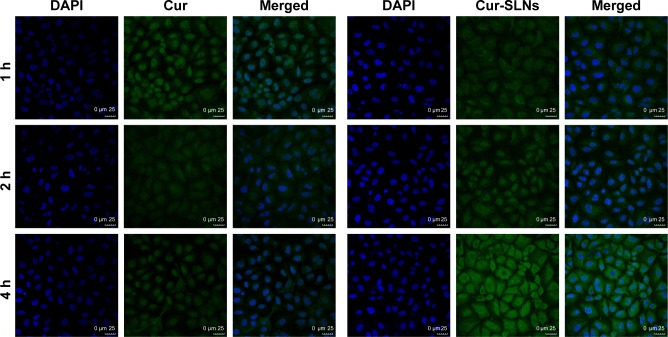

Cellular uptake and localization

A549 cells were incubated with Cur-SLNs or free Cur at the same concentration (15 μM) for 1, 2, and 4 h at 37°C and then imaged under a confocal fluorescence microscope. As shown in Figure 5, free Cur showed a little green fluorescence at 1 h, whereas at 4 h, its fluorescence intensity disappeared, possibly due to degradation from the time-dependent absorption spectra, which was also confirmed by other studies as mentioned earlier. However, cells treated with Cur-SLNs showed gradually increasing fluorescence intensity over time; when observed at 4 h of incubation, the cellular uptake of Cur-SLNs was much higher than that of free Cur. It has been reported that SLNs could enhance drug bioavailability by increasing Cur delivery and residence time through adhesion to the cellular surface.38,39 The 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride staining data revealed that the nuclear morphology remained unchanged in the dark, indicating the noncytotoxic nature of Cur-SLNs or free Cur in the dark.

Figure 5.

Intracellular uptake study of free Cur and Cur-SLNs in A549 cells.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; DAPI, 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride.

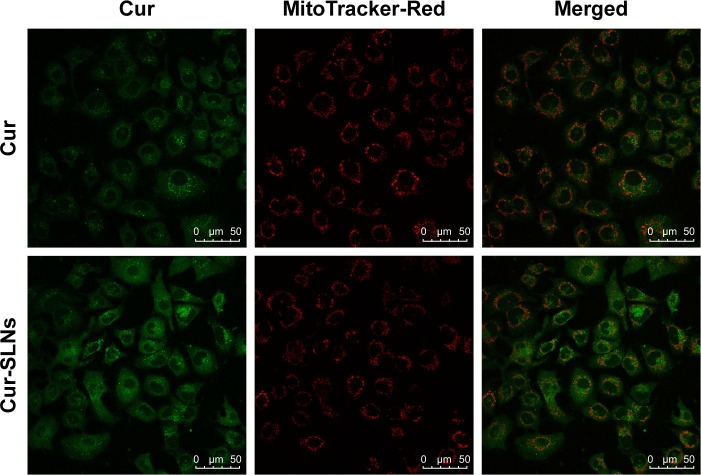

In order to evaluate the capability of Cur to selectively target mitochondria, colocalization imaging experiments were performed in A549 cells. Mito-Tracker Green, a commercial mitochondrial dye, was employed to label mitochondria. As shown in Figure 6, the fluorescence of Cur overlapped well with that of Mito-Tracker Green. This could suggest that Cur-SLNs and free Cur were specifically bound to intracellular mitochondria. Also, accumulation of Cur-SLNs–treated cells was even much stronger than free Cur in the mitochondria.

Figure 6.

Cellular uptake of Cur and Cur-SLNs at 4 h.

Note: Confocal imaging of the colocalization of Cur and Cur-SLNs with mitochondria (MitoTracker-Red).

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles.

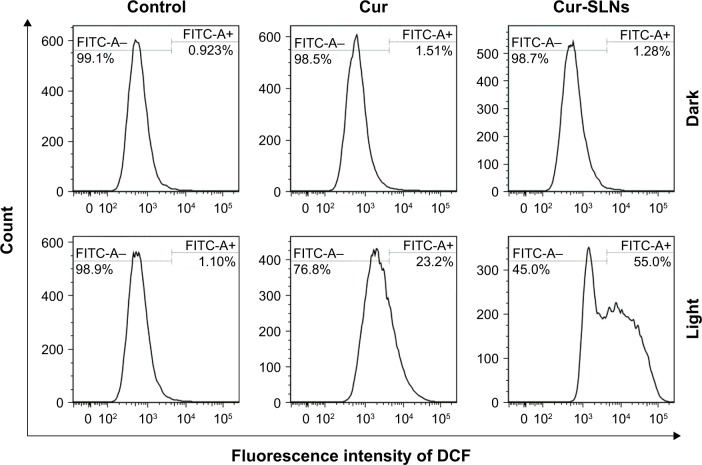

ROS generation of Cur-SLNs

As shown in Figure 7, no obvious change in ROS was detected in the dark group. When A549 cells were directly exposed to 430 nm, the Cur-SLNs were irradiated to produce more ROS (55.0%) than the free Cur (23.2%). This assay indicated that photoactivation of Cur-SLNs increased intracellular ROS levels, resulting in a better PDT effect in killing cancer cells.

Figure 7.

DCFH-DA/DCFH assay performed for the detection of ROS generation by Cur and Cur-SLNs in A549 cells.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; DCFH, dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

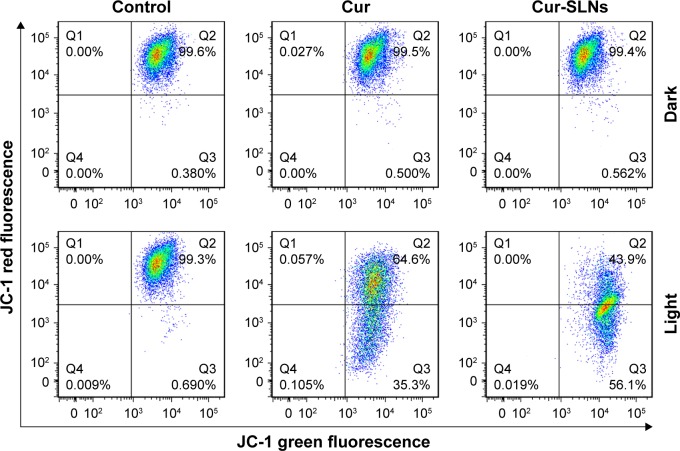

Cur-SLNs induced mitochondrial dysfunction

In order to investigate whether Cur-SLN–induced apoptosis in A549 cells involves alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential, we used a JC-1 probe to monitor the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential of Cur-SLNs–treated cells by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 8, the JC-1 monomer/aggregate ratio was 0.55 in Cur-treated group, while it was 1.28 in the Cur-SLNs–treated group. The data suggest that treating A549 cells with Cur-SLNs resulted in disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential. Also, mitochondrial dysfunction might be involved in the process of Cur-SLN–induced apoptosis.

Figure 8.

FACS analysis of JC-1 stained cells for the detection of mitochondrial membrane potential changes induced by Cur and Cur-SLNs in A549 cells.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; JC-1, 3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide.

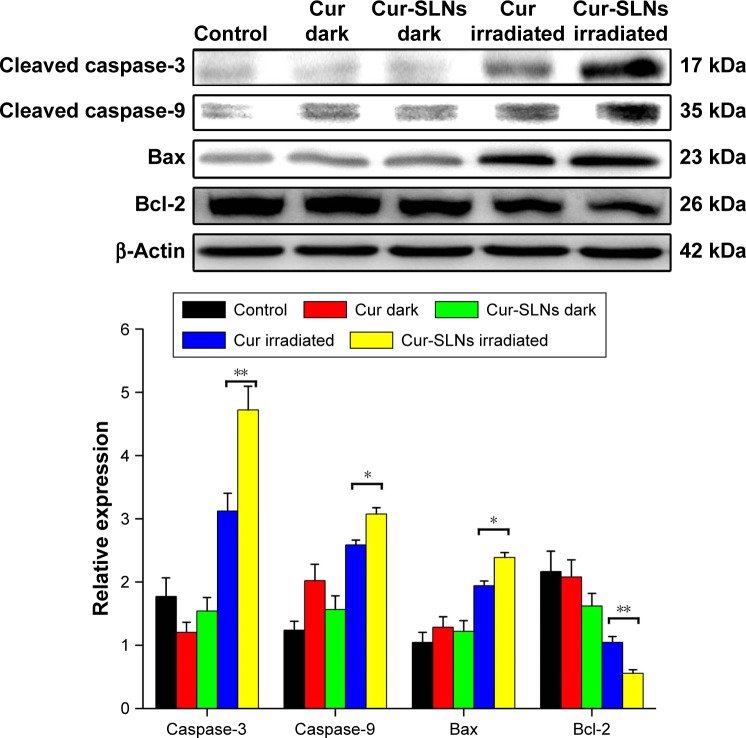

Western blot analysis

Figure 9 reveals that after PDT treatment, the expression levels of Bax, caspase-3, and caspase-9 were upregulated and the expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 was downregulated, compared to dark treatment. After exposure, the expression levels of Bax, caspase-3, and caspase-9 induced by Cur-SLNs were much higher than those of free Cur-treated group; also, the expression of Bcl-2 was lower compared to that with Cur treatment. This result shows that SLNs could enhance the PDT effects of Cur.

Figure 9.

Expression of caspase-3, caspase-9, Bax, and Bcl-2 proteins by Western blotting analysis after 20 min of irradiation using a 430 nm LED.

Notes: The statistical significances in Cur and Cur-SLNs groups were determined using a two-sample Student’s t-test. The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation of three experiments; *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: Cur, curcumin; Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; LED, light-emitting diode.

Discussion

In a previous study, we encapsulated Cur into SLNs to improve its dispersity and stability for enhancing the anti-inflammatory activity of Cur.8 In this study, we demonstrated that SLNs could act as an effective carrier to deliver Cur and exhibit a higher photodynamic toxicity to A549 cells.

In order to explore the mechanism by which Cur-SLNs induced higher PDT activity in comparison with free Cur, confocal microscopy was used, which showed that the fluorescence intensity of Cur-SLNs could be observed within 1 h and became stronger after 4 h of incubation in A549 cells, while free Cur showed only weak green fluorescence. It could be deduced that Cur-SLNs were more stable and soluble than free Cur. Coincubation of A549 cells with Cur-SLNs and Mito-Tracker Deep Red showed that the drug was enriched in mitochondria. The mitochondrion is an essential organelle supplying energy and regulating apoptosis in cells, usually be used as a target in PDT.40

It is well known that Cur exposed to 430 nm light could generate a large amount of ROS, inducing the apoptosis of cancer cells.32,37,41 Cytotoxic intracellular ROS can cause damage to mitochondria in cells, resulting in cell death. Our results demonstrated that SLN was a good drug delivery system for Cur, which enhanced its intracellular uptake and slowed down its hydrolysis in PDT.

Previous reports show that loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is an early event in apoptosis. This is because the ROS burst activates an inner membrane anion channel and promotes the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore by oxidation of matrix glutathione.42 High levels of ROS can disrupt the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and destroy the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane, resulting in immediate dissipation of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and osmotic swelling of the mitochondrial matrix.43,44 Once there is no exchange of small molecules between the matrix and the cytoplasm, mitochondrial energy production stops and cell apoptosis occurs. In our study, the mitochondrial membrane potential of Cur-SLN–treated group showed more serious collapse compared to that of free Cur group.

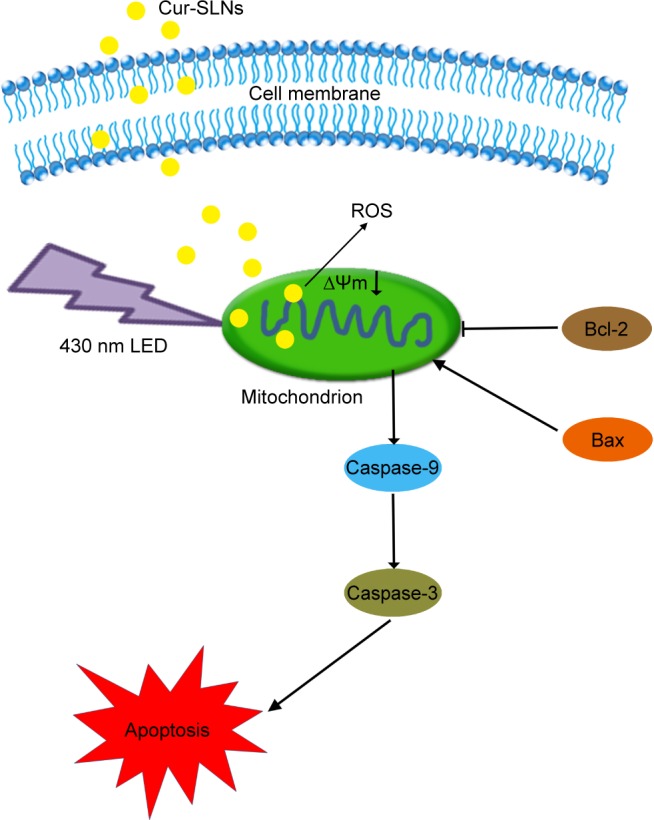

In order to investigate the underlying molecular mechanism, the proapoptotic protein Bax and the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 were measured by Western blotting. The antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 can counteract the proapoptotic activity from Bax, and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 might be another useful factor in the cellular threshold for undergoing apoptosis induced by PDT.45 Many studies have shown that activation of the caspase protein family triggers the apoptotic process in cells. Caspase-9 cleaved and activated procaspase-3.36,46–49 Activation of caspase-3 resulted in the apoptosis of cell, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and internucleosomal DNA fragmentation. Figure 10 shows that after PDT treatment, the expression levels of caspase-3 and caspase-9 improved significantly and the expression in Cur-SLN–treated group was higher compared to that in Cur-treated group. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was lower in Cur-SLN–treated group compared to that in Cur-treated group. This indicates that induction of apoptosis after PDT treatment may be through a caspase-dependent mechanism and that Cur delivered by SLNs can induce more apoptosis of A549 cells. In conclusion, Cur-SLNs may be used as a promising therapeutic agent for cancer treatment.

Figure 10.

The signaling pathways and mechanism of Cur-SLNs in A549 cells.

Abbreviations: Cur-SLNs, curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles; LED, light-emitting diode; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that SLNs could be used as a potential drug delivery carrier which largely enhances the cancer cell killing efficiency of Cur exposed to 430 nm light. This surprising effect was because the SLN-based delivery system dramatically increased intracellular shuttling of Cur, enhanced the hydrolytic stability of Cur, and increased light-induced ROS formation. Altogether, our data showed the promise of using SLNs in combined phototherapies with synergistic efficacies for treating cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 31570849, 81671105), the National key research and development program (Grant No 2016YFA0100800), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dou QQ, Teng CP, Ye E, Loh XJ. Effective near-infrared photodynamic therapy assisted by upconversion nanoparticles conjugated with photosensitizers. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:419–432. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S74891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu Z, Sun Q, Pan W, Li N, Tang B. A near-infrared triggered nanophotosensitizer inducing domino effect on mitochondrial reactive oxygen species burst for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9(11):11064–11074. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaing Oo MK, Yang YM, Hu Y, Gomez M, Du H, Wang HJ. Gold nanoparticle-enhanced and size-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species from protoporphyrin IX. ACS Nano. 2012;6(3):1939–1947. doi: 10.1021/nn300327c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Fei B, Halig LV, et al. Targeted iron-oxide nanoparticle for photodynamic therapy and imaging of head and neck cancer. ACS Nano. 2014;8(7):6620–6632. doi: 10.1021/nn501652j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S. Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71(10):1397–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(4):787–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Zhu RR, Sun DM, et al. Intracellular uptake of curcumin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles exhibit anti-inflammatory activities superior to those of curcumin through the NF-kappa B signaling pathway. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11(3):403–415. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2015.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araujo NC, Fontana CR, Bagnato VS, Gerbi ME. Photodynamic effects of curcumin against cariogenic pathogens. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30(7):393–399. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee S, Prasad P, Hussain A, Khan I, Kondaiah P, Chakravarty AR. Remarkable photocytotoxicity of curcumin in HeLa cells in visible light and arresting its degradation on oxovanadium(IV) complex formation. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48(62):7702–7704. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33576j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khorsandi K, Hosseinzadeh R, Fateh M. Curcumin intercalated layered double hydroxide nanohybrid as a potential drug delivery system for effective photodynamic therapy in human breast cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2015;5(114):93987–93994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koon H, Leung AW, Yue KK, Mak NK. Photodynamic effect of curcumin on NPC/CNE2 cell. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25(1–2):205–215. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v25.i1-2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garai A, Pant I, Banerjee S, Banik B, Kondaiah P, Chakravarty AR. Photorelease and cellular delivery of mitocurcumin from its cytotoxic cobalt(III) complex in visible light. Inorg Chem. 2016;55(12):6027–6035. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar T, Butcher RJ, Banerjee S, Mukherjee S, Hussain A. Visible light-induced cytotoxicity of a dinuclear iron(III) complex of curcumin with low-micromolar IC50 value in cancer cells. Inorganica Chim Acta. 2016;439:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye Y, Li Y, Fang F. Upconversion nanoparticles conjugated with curcumin as a photosensitizer to inhibit methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in lung under near infrared light. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:5157–5165. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S71365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar T, Banerjee S, Mukherjee S, Hussain A. Mitochondrial selectivity and remarkable photocytotoxicity of a ferrocenyl neodymium(III) complex of terpyridine and curcumin in cancer cells. Dalton Trans. 2016;45(15):6424–6438. doi: 10.1039/c5dt04775g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitra K, Gautam S, Kondaiah P, Chakravarty AR. The cis-diammineplatinum(II) complex of curcumin: a dual action DNA crosslinking and photochemotherapeutic agent. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(47):13989–13993. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee S, Pant I, Khan I, et al. Remarkable enhancement in photocytotoxicity and hydrolytic stability of curcumin on binding to an oxovanadium(IV) moiety. Dalton Trans. 2015;44(9):4108–4122. doi: 10.1039/c4dt02165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee S, Chakravarty AR. Metal complexes of curcumin for cellular imaging, targeting, and photoinduced anticancer activity. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(7):2075–2083. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):807–818. doi: 10.1021/mp700113r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan MH, Huang TM, Lin JK. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27(4):486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma RA, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:453–470. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand P, Nair HB, Sung B, et al. Design of curcumin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles formulation with enhanced cellular uptake, and increased bioactivity in vitro and superior bioavailability in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79(79):330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Yadav VR, Prasad S, Kannappan R, et al. Cyclodextrin-complexed curcumin exhibits anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activities superior to those of curcumin through higher cellular uptake. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(7):1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Anitha A, Maya S, Deepa N, et al. Efficient water soluble O- carboxymethyl chitosan nanocarrier for the delivery of curcumin to cancer cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83(2):452–461. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yallapu MM, Ebeling MC, Chauhan N, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Interaction of curcumin nanoformulations with human plasma proteins and erythrocytes. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6(1):2779–2790. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez AP, Casasco A, Schilrreff P, et al. Enhanced photodynamic leishmanicidal activity of hydrophobic zinc phthalocyanine within archaeolipids containing liposomes. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9(1):3335–3345. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S60543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Zhu R, Sun X, Zhu Y, Liu H, Wang SL. Intracellular uptake of etoposide-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles induces an enhancing inhibitory effect on gastric cancer through mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9(4):3987–3998. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S64103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Zhu R, Xie Q, et al. Enhanced bioavailability and efficiency of curcumin for the treatment of asthma by its formulation in solid lipid nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;7(7):3667–3677. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farboud ES, Nasrollahi SA, Tabbakhi Z. Novel formulation and evaluation of a Q10-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle cream: in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:611–617. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S16815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie S, Pan B, Shi B, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticle suspension enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of praziquantel against tapeworm. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6(1):2367–2374. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S24919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan Y, Min Y, Hu Q, Xing B, Liu B. NIR photoregulated chemo- and photodynamic cancer therapy based on conjugated polyelectrolyte-drug conjugate encapsulated upconversion nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2014;6(19):11259–11272. doi: 10.1039/c4nr03302g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui S, Yin D, Chen Y, et al. In vivo targeted deep-tissue photodynamic therapy based on near-infrared light triggered upconversion nanoconstruct. ACS Nano. 2012;7(1):676–688. doi: 10.1021/nn304872n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian B, Wang C, Zhang S, Feng L, Liu Z. Photothermally enhanced photodynamic therapy delivered by nanographene oxide. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7000–7009. doi: 10.1021/nn201560b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahoo SK, Panyam J, Prabha S, Labhasetwar V. Residual polyvinyl alcohol associated with poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles affects their physical properties and cellular uptake. J Control Release. 2002;82(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Wang X, Zhang S, Wang P, Zhang K, Liu Q. Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer, triggers mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in ECA-109 cells via production of reactive oxygen species. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9(1):3077–3090. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S59302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar T, Banerjee S, Hussain A. Remarkable visible light-triggered cytotoxicity of mitochondria targeting mixed-ligand cobalt(III) complexes of curcumin and phenanthroline bases binding to human serum albumin. RSC Adv. 2015;5(22):16641–16653. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohanty C, Acharya S, Mohanty AK, Dilnawaz F, Sahoo SK. Curcumin- encapsulated MePEG/PCL diblock copolymeric micelles: a novel controlled delivery vehicle for cancer therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5(3):433–449. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxena V, Hussain MD. Polymeric mixed micelles for delivery of curcumin to multidrug resistant ovarian cancer. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2013;9(7):1146–1154. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2013.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hackbarth S, Schlothauer J, Preuß A, Röder B. New insights to primary photodynamic effects – singlet oxygen kinetics in living cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2010;98(3):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao ZX, Li YC, Lu HM, Sung HW. A genetically-encoded KillerRed protein as an intrinsically generated photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35(1):500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang G, Liu C, Liu J, et al. Exopolysaccharide from Trichoderma pseudokoningii induces the apoptosis of MCF-7 cells through an intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;136:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou T, Dang Y, Zheng YH. The mitochondrial translocator protein, TSPO, inhibits HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis via the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation pathway. J Virol. 2014;88(6):3474–3484. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03286-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang S, Yang L, Ling X, et al. Tumor mitochondria-targeted photodynamic therapy with a translocator protein (TSPO)-specific photosensitizer. Acta Biomater. 2015;28:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou Z, Zhang Y, Deng K, et al. UV-emitting upconversion-based TiO2 photosensitizing nanoplatform: near-infrared light mediated in vivo photodynamic therapy via mitochondria-involved apoptosis pathway. ACS Nano. 2015;9(3):2584–2599. doi: 10.1021/nn506107c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang F, Yang X, Ma L, et al. Multifunctional up-converting nanocomposites with multimodal imaging and photosensitization at near-infrared excitation. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(47):24597–24604. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sivanantham B, Sethuraman S, Krishnan UM. Combinatorial effects of curcumin with an anti–neoplastic agent on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) through the regulation of EGFR–ERK1/2 and apoptotic signaling pathways. ACS Comb Sci. 2016;18(1):22–35. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biswas R, Chung PS, Moon JH, Lee SH, Ahn JC. Carboplatin synergistically triggers the efficacy of photodynamic therapy via caspase 3-, 8-, and 12-dependent pathways in human anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(3):995–1007. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu R, Wang Q, Zhu Y, et al. pH sensitive nano layered double hydroxides reduce the hematotoxicity and enhance the anticancer efficacy of etoposide on non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Biomater. 2015;29:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]