Abstract

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a widely acknowledged trauma that affects a substantial number of boys/men and has the potential to undermine mental health across the lifespan. Despite the topic's importance, few studies have examined the long-term effects of CSA on mental health in middle and late life for men. Most empirical studies on the effects of CSA have been conducted with women, non-probability samples, and samples of young or emerging adults with inadequate control variables. Based on complex trauma theory, the current study investigated: a) the effect of CSA on mental health outcomes (depressive symptoms, somatic symptom severity, hostility) in late life for men, and b) the moderating effects of childhood adversities and masculine norms in the relationship between CSA and the three mental health outcomes. Using a population-based sample from the 2004-2005 Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, multivariate analyses found that CSA was positively related to both depressive and somatic symptoms and increased the likelihood of hostility for men who reported a history of CSA. Both childhood adversities and masculine norms were positively related to the three outcomes for the entire sample. Among CSA survivors, childhood adversities exerted a moderating effect in terms of depressive symptoms. Mental health practitioners should include CSA and childhood adversities in assessment and treatment with men. To more fully understand the effects of CSA, future studies are needed that use longitudinal designs, compare male and female survivors, and examine protective mechanisms such as social support.

Keywords: child sexual abuse, male survivors, complex trauma, adverse childhood experiences, somatic symptoms, depression

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a widely acknowledged trauma that affects a substantial number of boys/men. CSA is “any completed or attempted sexual act, sexual contact, or non-contact sexual interaction with a child” (Gilbert et al., 2009, p. 69). According to a recent meta-analysis, 8% of men worldwide had experienced some form of sexual abuse prior to the age of 18 (Stoltenborgh, van Ijzendoorm, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011). In addition to non-contact sexual abuse (i.e., exposure to sexual activity, filming, or flashing) and sexual touching, 5% of men reported that they experienced penetrative sexual abuse in childhood (Gilbert et al., 2009). Due to the intricate web of barriers to reporting and disclosure (Easton, Saltzman, & Willis, 2014), actual incidence rates of CSA for boys/men are likely to be higher.

This high prevalence is concerning because research suggests that CSA can negatively impact survivors; mental health throughout their lives (Gilbert et al., 2009). In the CSA literature, however, the vast majority of studies focused on women; empirical evidence on the long-term impact of sexual victimization for boys/men is tenuous (Holmes & Slap, 1998). Few studies have examined the effects of CSA on men's mental health in midlife or late life. Studies have revealed that men who were sexually abused are likely to experience impaired masculine identity, stigma related to perceived homosexuality, self-identity disruptions, delays in disclosure, and lack of access to support resources (Easton, et al., 2014; O'Leary & Barber, 2008), all factors that could affect mental health. Because of the possibility of gender-specific, long-term differences in the effects of CSA, scholars have called for more research with male survivors (Spataro, Moss, & Wells, 2001).

To address this gap in the literature, the current study assessed the impact of CSA on the mental health of men in middle and late life using data collected from a large, population-based survey. Guided by complex trauma theory (Herman, 1992; Van der Kolk, 1996), we examined the association between CSA and depressive symptoms, somatic symptom severity, and hostility in late adulthood. To improve our understanding of mechanisms that might heighten the impact of CSA, we also investigated potential moderating effects of childhood adversities and masculine norms. By advancing the knowledge base on this neglected population, this investigation will inform intervention strategies and future research that could improve the psychological health of men with histories of CSA.

Literature

Complex Trauma Theory

The diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was introduced in the third edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (APA, 1980), largely in response to the mental health needs of returning Vietnam War veterans (Courtois, 2004). Despite its clinical utility as the foundational trauma disorder, clinicians and researchers noted that the symptom triad (i.e., re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal) of PTSD captured a limited range of symptoms that trauma survivors face (Ford & Courtois, 2009). In the early and mid-1990s, scholars introduced the term complex trauma (Herman, 1992; Van der Kolk, 1996), defined as “...a type of trauma that occurs repeatedly and cumulatively, usually over a period of time and within specific relationships and contexts” (Courtois, 2004, p. 412). In addition to fear-based responses inherent in a PTSD diagnosis, survivors of complex trauma such as child abuse often experience additional problems in multiple domains (e.g., affective, self-concept, relational) due to compromised self-organization systems (Briere & Spinazzola, 2005; Ford & Courtois, 2009; Van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005).

More recently, scholars have conceptualized traumatic stressors on a continuum ranging from single-incident, adult-onset events of short duration (e.g., automobile accident, natural disaster) to multiple incident, early-onset events over an extended period of time (e.g., child physical abuse, child neglect; Briere & Spinazzola, 2005). Other attributes of complex stressors include: betrayal of trust by caregivers, occurrence during crucial developmental periods in the lives of victims, and co-occurrence with other environmental stressors that augment suffering (Ford & Courtois, 2009; Van der Kolk et al., 2005). Additionally, invasive stressors of an interpersonal nature such as sexual abuse typically invoke tremendous stigma and shame (Briere & Spinazzola, 2005). Survivors of complex stressors are more likely to experience chronic, long-term problems in interpersonal relations and affect regulation such as depression, somatic illness, and anger or hostility (Cloitre, Garvert, Brewin, Bryant, & Maercker, 2013; Van der Kolk et al., 2005).

Empirical Research on CSA

As a prototypal example of a complex traumatic stressor, CSA has the capacity to undermine mental health across the lifespan. An extensive empirical literature has documented linkages between CSA and psychological functioning in adulthood including affective disorders such as depression (Holmes & Slap, 1998; Maniglio, 2009). Cutajar et al. (2010) analyzed data from childhood medical records and public psychiatric databases on a large sample of CSA survivors (80.1% female) in early adulthood. They found that survivors of CSA utilized mental health services at a rate that was 3.65 higher than their non-abused counterparts and had higher rates of a wide range of clinical disorders including depression. Thomas, DiLillo, Walsh and Polusny (2011) conducted a cross-sectional study with 110 female veterans ranging in age from 22 to 65 years and found that CSA predicted depression. In a secondary data analysis of 7,700 Australian young adult women (Coles, Lee, Taft, Mazza & Loxton, 2015), researchers established that people with a history of CSA were 1.4 times more likely to be depressed in the past three years than non-abused counter-parts. Conversely, some studies did not find relationships between CSA and major affective disorders in adulthood for men (Cutajar et al., 2010; Molnar, Buka, & Kessler, 2001; Spataro, Mullen, Burgess, Wells, & Moss, 2004).

The research base on CSA and outcomes such as somatic disorders or hostility in adulthood is less developed. Nonetheless, the results of several studies indicate that CSA is related to a higher lifetime rate of somatic or physical health problems. Nelson, Baldwin, and Taylor (2012) completed an integrative literature review and found that adults with a history of CSA are more likely to experience medically unexplained symptoms (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome) than adults with no abuse history. Other studies with convenience samples of women have found that CSA is related to a greater likelihood of experiencing bodily pain (Coles et al., 2015) and migraine headaches (Bunevicius et al., 2013) in early and middle adulthood. One prospective study that included male survivors, however, found no association between CSA and somatic problems (Spataro et al., 2004). Several qualitative studies have found that CSA was related to anger and rage among men (Fater & Mullaney, 2000; Lisak, 1994; Sigurdardottir, Halldorsdottir, & Bender, 2012). The results of two other studies indicated that CSA increases the risk of personality (e.g., anti-social) or conduct disorders, often characterized by anger and hostility, for men (Fergusson, McLeod, & Horwood, 2013; Spataro et al., 2004). Few quantitative studies, though, have directly assessed whether CSA is related to somatic disorders or hostility in middle or late adulthood for male survivors.

Complex trauma theory asserts that environmental stressors that co-occur with traumas such as CSA can augment suffering for survivors. A prominent class of environmental stressors, adverse childhood experiences (ACE; e.g., physical abuse or neglect, parental substance use), is relatively common in the general population (Chartier, Walker, & Naimark, 2010; Dong et al., 2004) and frequently co-occurs with CSA (Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003; Dong et al., 2004; Easton, 2012). In terms of the long-term effects of ACE, Felitti et al.'s (1998) pioneering research documented links between ACE and health risks for outcomes such as alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts. Chapman et al. (2004) analyzed data from a large sample of adults (N = 9,460; 46% men) and found that exposure to ACE was associated with an increased risk of depressive disorders. More recently, a systematic review (Kalmakis & Chandler, 2014) concluded that ACE was associated with health risk behaviors, developmental disruptions, physical and psychological conditions, and increased health care utilization in adulthood. In addition, there is growing evidence of the cumulative negative effects of multiple ACE on adult mental health (Chapman et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2004; Felitti et al., 1998) and, more specifically, that childhood adversities may predict mental distress among men with histories of CSA (Easton, 2014). However, more research is needed to assess the potential interaction effects of CSA and ACE on men's mental health.

Furthermore, complex trauma theory posits that stigma can heighten negative outcomes among CSA survivors. The experience of CSA violates several norms of masculinity (e.g., heterosexuality, winning, dominance, emotional control); many survivors experience shame and stigma as a result of their abuse (Easton et al., 2014; Holmes & Slap, 1998; Spataro et al., 2001). Some men may respond to victimization by overcompensating and adopting hyper-masculine personas in adulthood (Lisak, 1994). Among the general population, however, rigid notions of masculinity have been associated with lower psychological well-being (Alfred, Hammer, & Good, 2014), psychological distress (Wong, Owen & Shea, 2012), depression (Mahalik & Rochlen, 2006), and negative attitudes towards help-seeking (Levant, Wimer, & Williams, 2009). Few studies have examined the relationship between gender norms and mental health for sexually abused men. Among a large non-probability sample of male survivors of CSA, high conformity to masculine norms was associated with mental distress (Easton, 2014) and suicidality (Easton, Renner, & O'Leary, 2013).

In reviewing the literature, it is evident that more research is needed to surmount some of the limitations of existing studies. To understand the potential lifespan effects of CSA, research should expand the conceptualization of long-term effects beyond studies with adolescents/young adults and examine data from older adults decades after the abuse occurred. Also, most research to date has been with female survivors (e.g., Coles et al., 2015), small convenience samples (e.g., Thomas et al., 2011), or confirmed cases of CSA in medical records (e.g., Cutajar et al., 2010). To advance the empirical knowledge base, the current study is based on a representative, population-based sample, uses a matched comparison group, and controls for confounding variables such as family environment, as suggested by Maniglio (2009). The investigation has two primary aims. First, we assess whether CSA is related to multiple mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms, somatic symptom severity, and hostility) in middle and late adulthood for men. Second, we examine whether childhood adversities or masculine norms moderate the relationships between CSA and long-term mental health outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) is a long-term population-based study of a random sample of 10,317 men and women who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957 and 5,823 of their randomly selected siblings (Hauser & Roan, 2006). After the first interview in 1957, the graduates were re-interviewed at subsequent time points by telephone or mailed questionnaires: 1975 (35-36 years of age), 1993 (53-54 years of age), 2004 (64-65 year of age), and 2011 (71-72 years of age). Data was also collected from a randomly selected sibling of the graduate in three corresponding waves (1977, 1994, and 2005). The current study is a secondary analysis of data from the 2004-2005 WLS interviews, which included data on childhood abuse and other early life adversities. In 2004, 6,845 graduates completed the telephone survey and returned mail questionnaires. In 2005, 3,977 siblings completed both phone interviews and mail questionnaires. The pooled sample of male graduates and siblings from the 2004-2005 WLS was 5,013 respondents (graduates: 3,145; siblings: 1,868).

Study Sample

The study sample was comprised of respondents who reported a history of being sexually abused and a matched comparison group of those who reported no history of CSA. In the 2004-2005 WLS dataset, a total of 129 respondents reported having experienced sexual abuse during childhood. From the remaining 4,884 respondents, we used stratified random sampling to select a comparison group (i.e., no history of CSA) that had similar socio-demographic characteristics with the respondents who reported a history of CSA. Using a matched comparison group is valuable because it replicates a randomized experiment and reduces confounding bias when comparing the abused and non-abused groups, important considerations when evaluating causal relationships between CSA and adverse outcomes in later life (Bolen, 2001; Osborne, 2008).

Consistent with other research that has used matched comparison groups from the WLS (Seltzer, Floyd, Song, Greenberg, & Hong, 2011; Song, Floyd, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Hong, 2010), we used age and education as stratification variables to identify strata. We first examined the distribution of these variables among sexually abused men to determine the strata levels. By comparing the number of people in each stratum between the CSA group and the comparison pool, the final matching ratio was derived as 1:18. We then randomly selected respondents from each stratum based on the final matching ratio. As a result, the comparison group consisted of a stratified random sample of 2,322 respondents. A series of t-tests and χ2 tests confirmed that there were no significant differences between men in the CSA and comparison groups in terms of age, marital status, educational attainment, household income, and health status. Combining the two groups, our final study sample consisted of 2,451 men. Thus, the abused group (n = 129) constituted 5.3% of the total sample.

Sample Characteristics

The average age of respondents was 64.2 years (range = 44 - 84). The majority of respondents reported that they were married (85.9%) and in good or excellent health (84.2%). On average, respondents indicated that they had completed 14.5 years of education (i.e., high school degree and some college) and that their fathers had completed 10.1 years (i.e., less than high school degree). Almost one-third of respondents (29.7%) reported that they lived in rural areas during childhood. The mean (squared) household income was 255.9 (SD=136.8), which equates to approximately $84,000 (range= $0-$710,000).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). This scale has been widely used to assess later-life depression (Haringsma, Engels, Beekman, & Spinhoven, 2004) The items ask about the frequency of occurrence of common depressive symptoms such as depressed mood, feeling of worthlessness/hopelessness, and loss of appetite. Response choices ranged from zero to seven, indicating the number of days a respondent experienced each symptom in the past week. Response choices were summed to produce a total score (range = 0 - 140), with higher scores indicating high levels of depressive symptoms. In the regression analyses, the square root of the depression scores was used due to the high skewness of the variable. In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the CES-D scale was 0.87 and the mean was 3.2 (SD=1.8; range=0-10.6).

Somatic Symptom Severity

Somatic symptom severity was assessed using 16 items based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2002). The items asked respondents whether they experienced specific physical symptoms in the past six months (e.g., back pain/strain, shortness of breath). Response choices for each item were based on a four-point Likert scale: none (1), a little (2), some (3), and a lot (4). Response choices were summed to produce a total score (range = 0 - 64) with higher scores indicating high levels of somatic symptom severity. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.82 and the mean was 20.2 (SD=7.9; range=1-56).

Hostility

Hostility was measured with three items that were derived from the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (Spielberger, 1988). The stem and items read: “On how many days during the past week did you (a) feel irritable, or likely to fight or argue?; (b) feel like telling someone off?; (c) feel angry or hostile for several hours at a time?” Response choices ranged from zero to seven days and were summed to produce a total score (range = 0 - 21) with higher scores indicating more hostility. Due to high levels of skewness, the summary score was recoded as a binary variable: feeling hostile (1; if respondents reported hostility scores of 3 or more) and not feeling hostile (0). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.86. In this sample, 14.9% (n=356) reported feeling hostile.

Sexually abused in childhood

To assess for a history of CSA, we relied on four items from the WLS: “Up-until 18, to what extent (a) did your father have oral, anal, or vaginal sex with you against your wishes?; (b) did any other person have oral, anal, or vaginal sex with you against your wishes?; (c) did your father treat you in way that you consider sex abuse?; (d) did any other person treat you in way that you consider sex abuse?” Response choices for each item were based on a four-point Likert scale: not at all (1), a little (2), some (3), and a lot (4). Respondents who answered a little, some, or a lot for any of the four items were coded as having been sexually abused during childhood (1; no = 0), constituting 5.3% of the sample (n=129).

Childhood adversities

Childhood adversities were measured with items from the WLS that corresponded with major categories within the Adverse Childhood Experiences (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). The WLS contained items for seven of the ACE categories: emotional abuse, physical abuse, neglect, family dysfunction, parental divorce, witnessing domestic violence, and living with a household member with a substance problem (sexual abuse was used as an independent variable). For example, one item asked: “Up until you were 18, how often did you see a parent or one of your brothers or sisters get beaten at home.” Response choices were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to very often (5). For each of the seven item, responses of often (4) and very often (5) were recoded into yes (1). Responses were then were summed to produce a total score (range = 0 - 7) with higher scores indicating more childhood adversities. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.62. The mean score for childhood adversities was .8 (SD=1.22; range=0-7).

Masculine norms

Masculine norms were measured by a series of seven statements on stereotypical behavior and beliefs for men. Respondents were asked about the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “...a man should always try to project an air of confidence even if he really doesn't feel confident inside”, “...when a man is feeling pain he should not let it show”, and “...men have greater sexual needs than women.” Each item was measured on five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores on the seven items were summed (range = 0 – 35) with higher scores indicating more agreement with masculine norms. In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the masculine norms was 0.60. The mean score was 19.4 (SD=3.4; range=1-35).

Control variables

Sociodemographic characteristics, including age, marital status, educational attainment, total household income, self-rated health condition, and childhood background were controlled in the analyses. Marital status was coded as married (1) and non-married (0). Educational attainment was reported as the number of years of education completed by the respondent. Total annual household income was comprised of 14 different income sources (e.g., wages, investments, pension plans, other government programs) and reported in US dollars. For self-rated health, participants selected one of five response choices: very poor (1), poor (2), fair (3), good (4), and excellent (5). In our analyses, the good and excellent categories were collapsed into one category (1) and the very poor, poor, and fair were combined and used as a reference category (0). In order to control for childhood environmental factors, we included father's educational attainment (in years) and rural background. The rural background was assessed by a question in the 1957 survey that asked the population of the town in which graduate respondents attended high school. Those who used to live in a place with a population of less than 2,500 were coded as having been raised in a rural area (1; 0 = not rural).

Analytic procedures

After univariate and bivariate analyses, multiple regression analyses were performed. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to examine factors related to depressive and somatic symptom severity, controlling for sociodemographic variables. For the binary outcome of hostility, logistic regression was used. To correct for the graduates and siblings nested within a family, models were estimated using robust standard errors (Cameron & Miller, 2011). Diagnostic analyses indicated that all other conditions for regression models including normality and linearity assumptions were met.

The analyses were sequentially conducted. In Model 1, the CSA variable, as well as the control variables were entered. In Model 2, childhood adversities and masculine norm were added to examine their effects on mental health outcome variables. In Model 3, we added interaction terms (CSA × childhood adversities scores; CSA × masculine norms). The scores for childhood adversities and masculine norms were standardized before creating the interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991).

Item nonresponse for most measures was low (< 3%). To handle incomplete data, we conducted multiple imputation by chained equations in Stata 13.0, which generated five datasets with imputed values.

Results

Bivariate results

Table 1 presents correlations between all of the variables in the study. Table 2 presents the results of bivariate analyses between men who did and did not report being sexually abused in childhood. Mean comparisons indicated that men with a history of CSA had significantly higher scores on childhood adversities compared to non-abused adults (t(2,444) = −7.88, p < .001). In terms of the dependent variables, abused men reported higher levels of depressive symptoms (t(2,385) = −2.96, p < .05), and somatic symptom severity (t(2,274) = −4.20, p < .001). In addition, a higher percentage of men who were abused reported feeling hostile than their counterparts (χ2(1, N = 2,386) = 4.25, p < .05).

Table 1.

Correlation Table

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.37* | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 0.39* | 0.22* | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 0.05* | 0.09* | 0.04* | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.15* | 0.12* | 0.14* | 0.16* | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6 | 0.10* | 0.11* | 0.08* | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7 | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.06* | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8 | −0.02 | −0.07* | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.11* | −0.12* | 1.00 | |||||

| 9 | −0.09* | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.05* | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10 | −0.06* | −0.15* | −0.04* | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.19* | −0.23* | 0.32* | 0.05* | 1.00 | |||

| 11 | −0.08* | −0.08* | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.15* | 0.17* | 0.14* | 0.36* | 1.00 | ||

| 12 | −0.25* | −0.33* | −0.12* | −0.03 | −0.05* | −0.10* | −0.08* | 0.08* | 0.04* | 0.15* | 0.11* | 1.00 | |

| 13 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.00 | −0.16* | 0.04* | −0.12* | −0.11* | −0.04 | 1.00 |

Note: N = 2,451.

1. Depression

2. Somatic symptom severity

3. Feeling hostile

4. Sexually abused

5. Childhood adversities

6. Masculine norm

7. Age

8. Father's education

9. Married

10. Years of education

11. Total household income

12. Good/Excellent health condition

13. Raised in a rural area

p < .05

Table 2.

Bivariate Analyses of Key Variables

| CSA | Non-CSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood adversities | 1.64 (1.82)*** | .79 (1.16) |

| Masculine norm | 19.41 (3.41) | 19.39 (3.44) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.55 (2.02)* | 3.13 (1.81) |

| Somatic symptom severity | 23.08 (8.80)*** | 19.99 (7.86) |

| Feeling hostile (%) | 21.26* | 14.56 |

Notes: Values are means (standard deviation), or percentages where indicated. Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05

** p< .01

p < .001

Multivariate results

Depressive symptoms

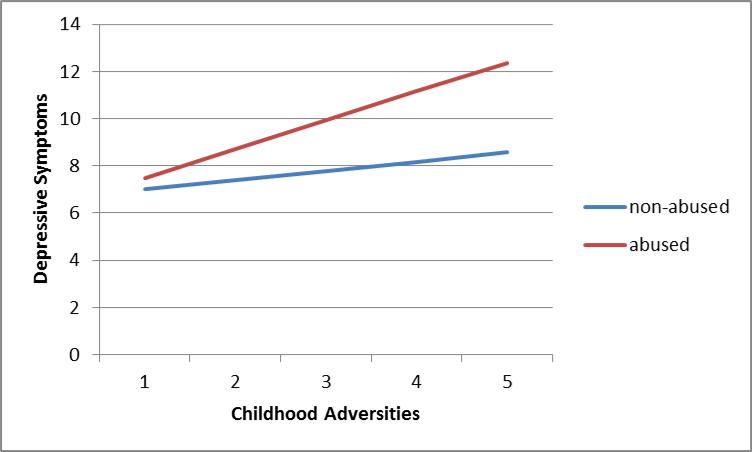

A summary of OLS regression results for depressive symptoms is presented in Table 3. In Model 1, CSA predicted significantly higher depressive symptoms (b = .37, p < .05), after controlling for the sociodemographic characteristics. Model 2 showed that higher scores for childhood adversities (b = .23, p < .001) and masculine norms (b = .15, p < .01) were associated with more depressive symptoms. However, after controlling for the childhood adversities and masculine norms, CSA was no longer significant (b = .22, p = ns). Model 3 evaluated the extent to which the effects of CSA were moderated by childhood adversities and masculine norms by examining interaction terms simultaneously. The results indicated that childhood adversities had significant interactions with CSA (b = .33, p < .05). Among all respondents, a greater number of childhood adversities was associated with more frequent depressive symptoms. However, the effect appears to be even stronger for the men with histories of CSA (see Figure 1). The average of the adjusted R2 values of Model 3 was 0.11. Throughout the three models, age, being married, total household income, and having good/excellent health were negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

OLS Analyses Predicting Depressive Symptoms

| Model 1 b (S.E.) |

Model 2 b (S.E.) |

Model 3 b (S.E.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | .37(.17)* | .22 (.17) | .04 (.16) |

| Childhood adversities | .23 (.04)*** | .19 (.04)*** | |

| Masculine norm | .15 (.05)** | .16 (.05)** | |

| CSA * Childhood adversities | .33 (.13)* | ||

| CSA * Masculine norm | −.10 (.24) | ||

| Age | −.03 (.01)*** | −.03 (.01)*** | −.03 (.01)*** |

| Married | −.35 (.11)** | −.34 (.11)** | −.35 (.11)** |

| Years of education | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.02) | −.01 (.02) |

| Total household income | −.00 (.00)* | −.00 (.00)* | −.00 (.00)* |

| Good/Excellent health condition | −1.25 (.11)*** | −1.19 (.11)*** | −1.19 (.11)*** |

| Father's education | −.00 (.01) | −.00 (.01) | .00 (.01) |

| Rural background | −.18 (.08)* | −.17 (.08)* | −.16 (.08)* |

| Constant | 7.17 (.65)*** | 6.84 (.65)*** | 6.81 (.64)*** |

| Adjusted R2 | .08 | .10 | .11 |

Notes: Standardized regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05

p< .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

Interaction between CSA and Childhood Adversities on Depressive Symptoms

Somatic symptom severity

Table 4 presents the results of OLS regression analyses predicting somatic symptom severity. In Model 1, CSA was associated with higher levels of somatic symptom severity (b = 2.84, p < .001). In Model 2, scores for childhood adversities and masculine norms were both related to somatic symptom severity (b = .75, p < .001; b = .54, p < .05, respectively). Even after controlling for childhood adversities, masculine norms, and sociodemographic variables, CSA still predicted greater levels of somatic symptom severity (b = 2.36, p < .01). The average of the adjusted R2 values of Model 3 was .14. However, none of the interaction terms were significant, indicating that the effects of CSA on psychosomatic symptoms do not differ by the childhood adversities and masculine norms. In all three models, age, education, and having good/excellent health condition were negatively associated with somatic symptom severity.

Table 4.

OLS Analyses Predicting Somatic Symptom Severity

| Model 1 b (S.E.) |

Model 2 b (S.E.) |

Model 3 b (S.E.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | 2.84 (.75)*** | 2.36 (.74)** | 1.97 (.62)** |

| Childhood adversities | .75 (.16)*** | .67 (.17)*** | |

| Masculine norm | .54 (.22)* | .57 (.23)* | |

| CSA * Childhood adversities | .65 (.54) | ||

| CSA * Masculine norm | −.60 (.68) | ||

| Age | −.07 (.04) | −.06 (.04)* | −.06 (.04)* |

| Married | .53 (.47) | .57 (.47) | .55 (.47) |

| Years of education | −.29 (.07)*** | −.26 (.07)*** | −.26 (.07) |

| Total household income | −.00 (.00) | −.00 (.00) | −.00 (.00) |

| Good/Excellent health condition | −6.92 (.52)*** | −6.71 (.53)*** | −6.69 (.53)*** |

| Father's education | −.03 (.05) | −.01 (.05) | −.01 (.05) |

| Rural background | −.40 (.36) | −.37 (.36) | −.37 (.36) |

| Constant | 34.59 (3.03)*** | 33.56 (2.98)*** | 33.47 (2.97)*** |

| Adjusted R2 | .13 | .14 | .14 |

Notes: Standardized regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05

p< .01

p < .001

Hostility

Table 5 summarizes the results of logistic regression models for the hostility outcome. In Model 1, the odds of feeling hostile were 57% higher among men who reported a history of CSA than non-abused men (OR = 1.57, p < .05), after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. In Model 2, CSA was not significantly related to a higher risk of feeling hostile, after accounting for the effects of the childhood adversities, masculine norms, and sociodemographic factors. Both higher scores on childhood adversities (OR = 1.37, p < .001) and masculine norms (OR = 1.20, p < .05) were associated with a greater risk of feeling hostile. Model 3, there were no significant moderating effects of childhood adversities and masculine norms on the association between CSA and the risk of feeling hostile. Across the models, age, having a good/excellent health condition, and rural background consistently showed negative associations with feeling hostile. The overall predictive models were statistically significant.

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Hostility

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | 1.57 (1.01, 2.43)* | 1.27 (.81, 1.99) | 1.02 (.59, 1.77) |

| Childhood adversities | 1.37 (1.24, 1.51)*** | 1.33 (1.19, 1.48)*** | |

| Masculine norm | 1.20 (1.02, 1.42)* | 1.22 (1.04, 1.43)* | |

| CSA * Childhood adversities | 1.25 (.94, 1.67) | ||

| CSA * Masculine norm | .85 (.50, 1.43) | ||

| Age | .95 (.93, .98)*** | .95 (.93, .98)*** | .95 (.93, .98)** |

| Married | 1.17 (.83, 1.65) | 1.20 (.85, 1.69) | 1.19 (.84, 1.68) |

| Years of education | .96 (.91, 1.01) | .97 (.92, 1.02) | .97 (.92, 1.02) |

| Total household income | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| Good/Excellent health condition | .47 (.34, .65)*** | .50 (.36, .69)*** | .50 (.36, .69)*** |

| Father's education | 1.00 (.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (.97, 1.04)* |

| Rural background | .72 (.55, .94)* | .73 (.56, .96)* | .74 (.56, .97)* |

| Constant | 14.07 (2.03, 97.31)** | 9.93 (1.32, 74.51)* | 9.64 (1.30, 72.55)* |

Notes: Odds ratios with confidence intervals in parentheses. Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05

p< .01

p < .001

Discussion

A central aim of this study was to examine whether CSA was related to several indicators of mental health for men in middle and late adulthood. After controlling for sociodemographic variables and childhood environmental factors (e.g., rural background, father's educational attainment), we found that CSA was positively related to all three psychological outcomes for men: depressive symptoms, somatic symptom severity, and hostility. These findings indicate that CSA can have potentially long-lasting effects. Based on the sample's mean age (64.2 years) and survey items that assessed sexual abuse prior to 18 years of age, our investigation suggests that CSA may be linked to harmful outcomes for many survivors four to five decades after its occurrence. The findings are consistent with complex trauma theory (Herman, 1992; Van der Kolk, 1996) which asserts that complex stressors such as CSA can disrupt key developmental processes in childhood and adolescence, leading to later life difficulties such as feelings of despair and hopelessness, unexplained physical complaints, and anger dysregulation (Cloitre et al., 2013; Van der Kolk et al., 2005).

For direct effects, our findings support the growing empirical literature on CSA and affective disorders (Holmes & Slap, 1998; Maniglio, 2009) and counter findings from studies that did not find such a relationship for male survivors (Cutajar et al., 2010; Molnar et al., 2001; Spataro et al., 2004). However, the latter three studies assessed links between CSA and affective disorders in early adulthood. For example, the mean age of male participants in studies by Cutajar et al. (2010) and Sparator et al. (2004) were, respectively, 31 years and 21 years. It is possible that CSA exerts a different effect on depressive symptoms at different life stages for men. Similar to female survivors (Coles et al, 2015; Bunevicius et al., 2013), male survivors in our study were also more likely to experience long-term somatic problems than men without abuse histories. This finding is inconsistent with those from Spataro et al.(2004), again, possibly due to the different mean age of participants. Building on previous qualitative studies (Fater & Mullaney, 2000; Lisak, 1994; Sigurdardottir, Halldorsdottir, & Bender, 2012), our results indicate that men with histories of CSA have a greater likelihood of experiencing feelings of hostility later in life than men with no abuse history. Certainly feelings of hostility or anger could be underlying mechanisms that disrupt functioning in various aspects of survivors’ lives (e.g., employment, relationship quality, life satisfaction). Overall, this investigation is one of the first population-based studies to find evidence of the negative influence of CSA on mental health outcomes for men later in the life course with a robust set of control variables.

A second aim of the study was to examine potential moderators of the relationship between CSA and long-term mental health outcomes. Complex trauma theory posits that other environmental stressors in childhood (e.g., ACE) can compound the effect of traumatic experiences on survivors’ mental health (Ford & Courtois, 2009; Van der Kolk et al., 2005). Additional stressors can magnify the psychological injury from CSA to the child and undermine potential recovery resources such as social support, both mechanisms that can contribute to psychological problems in adulthood. Childhood adversities have also been related to more severe forms of CSA among male survivors (Easton, 2012), another possible route to psychopathology. Our results supported a direct relationship between childhood adversities and three mental health outcomes among the entire sample of men, which is consistent with the growing literature on ACE (Chapman et al., 2004; Felitti et al., 1998; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2014). Beyond the direct effect, we found that childhood adversities had an additional effect of augmenting depressive symptoms in middle and late adulthood for men who were sexually abused. Interestingly, we did not find support that childhood adversities moderated the relationship between CSA and either somatic symptom severity or hostility. Once a person reaches a certain threshold of somatic symptoms or feelings of hostility (due to the direct effects, for example, of CSA or childhood adversities), it may be harder to detect and quantify an additional moderating effect. Another possibility is that more proximal factors (e.g., current life stressors) might exert greater influence through moderation than childhood adversities. Regardless, more research is needed to evaluate how third variables may interact with CSA to affect these two mental health outcomes in late life.

We examined a second potential moderator of the relationship between CSA and mental health outcomes: masculine norms. Due to shame and stigma, some survivors adopt rigid masculine norms as a coping mechanism (Lisak, 1994), which could undermine long-term mental health. Our analyses found a direct relationship between masculine norms and psychological outcomes across the entire sample, consistent with research in the general population (Alfred et al., 2014; Mahalik & Rochlen, 2006; Wong et al., 2012). However, we did not find a heightened effect of masculine norms among those who were sexually abused. Our results are inconsistent with two existing studies with male survivors (Easton, 2014; Easton et al., 2013) and may reflect measurement issues, which will be discussed later. A possible explanation is that masculine norms operate differently across generations, as the sample in the current study was nearly 15 years older than the samples in the two previous studies.

Implications for Practice

Due to the personal, interpersonal, and socio-political barriers to disclosure, men often guard the secret of being sexually abused in childhood well into adulthood and across the life course (Easton, 2013). However, some survivors will seek services for specific mental health problems such as depression, unexplained physical problems such as somatic concerns, or behavioral problems related to interpersonal aggression, violence, or feelings of hostility. In these cases, it is important for mental health professionals to include CSA in screening assessments. Because it may take survivors considerable time to form trusting therapeutic relationships conducive to disclosure and discussion of CSA, these survivors may not endorse CSA during initial intake assessments. Mental health providers should keep CSA as a possible underlying explanation for presenting psychological, physical, and behavioral issues during the course of treatment and consider reassessing for CSA in later sessions.

The interaction effect between CSA and childhood adversities on depressive symptoms also has important clinical implications for mental health practitioners working with male survivors of CSA experiencing depressive disorders. To gain a more thorough understanding of clients, therapists should include childhood social environment (more specifically, ACE) in intake assessments and clinical intervention plans. It is possible that male survivors harbor long-held feelings of shame, self-blame, or hopelessness as well as other disturbances in self-perception, all aspects of complex trauma (Ford & Courtois, 2009; Van der Kolk et al., 2005). Although distal factors that occurred forty or fifty years prior cannot be changed, the residual effect of these corrosive environments (as well as men's interpretation of their meaning) can be examined and, if necessary, reinterpreted through therapy sessions.

Directions for Future Research

The results have many implications for future research. First, this study demonstrated that CSA and childhood adversities have detrimental effects on mental health for men in middle and late life. To improve our understanding of similarities and differences between male and female survivors, future studies that include men and women should compare mental health outcomes of CSA based on gender. This type of research could help determine whether some outcomes traditionally associated with men (e.g., hostility) are unique to male survivors or also present with female survivors. Second, complex trauma theory (Herman, 1992; Van der Kolk, 1996) contends that early life stressors such as CSA not only impair affect regulation (and related mental health outcomes), but also undermine survivors’ ability to form meaningful, trusting relationships throughout their life (Cloitre et al., 2013; Van der Kolk et al., 2005). Given the important role that social support can play in coping with traumatic experiences, future studies should examine relationship patterns (e.g., marital, familial, friendship) for survivors of CSA across the life course and their potential to mitigate psychological problems. Finally, the current study used a cross-sectional design to investigate the relationships between CSA and multiple mental health outcomes in middle and late life for men. Although it was not possible to determine causal effects with this design, this study did establish important correlations among key concepts. Future studies can build on these findings by using longitudinal analytic techniques to examine life course trajectories for mental health outcomes.

Limitations

In interpreting the results of the current study, several considerations deserve mentioning. Although this population-based study used probability sampling, a noteworthy methodological improvement over previous studies with male survivors of CSA, the sample, nonetheless, was drawn from a single state (i.e., Wisconsin) that is not necessarily generalizable to the US population. One strength of the dataset is that it is “broadly representative of older White American men and women who have completed at least a high school education” (Herd, Carr, & Roan, 2014, p. 37). However, research on CSA and late-life mental health outcomes with more diverse samples (e.g., ethnicity, race, education level, income level, marital status) is needed to enrich our understanding of these relationships across the general population.

A second limitation is the percentage (2.6%) of male participants in the 2004-2005 WLS data wave who self-reported a history of CSA, a figure that is lower than current prevalence rates of CSA for boys (Gilbert et al., 2009; Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). Although it is possible that this cohort (many born in the 1940s) experienced a lower incidence of CSA, it is more likely that there was under-reporting due to a variety of methodological (e.g., retrospective recall or social desirability bias; limited number and type of screening items) and socio-cultural (e.g., generational stigma/shame) factors. If the latter is the case, participants in the comparison group with (un-reported) histories of CSA may have suppressed some of the results. Future studies that triangulate data with multiple sources (e.g., administrative records) or use more elaborate screening items could generate more accurate rates of CSA.

Finally, any secondary analysis is restricted in terms of the type of measures that are available to the researchers. Some of the measures in the current study (e.g., masculine norms) had acceptable internal consistency but lacked other established psychometric properties. Other measures (e.g., CSA items) did not elicit information related to duration or severity, important considerations in assessing the impact of the trauma. Using validated measures of masculinity (e.g., Conformity to Masculine Norms; Mahalik et al., 2003) and more nuanced indicators of CSA in future research studies with men would strengthen the knowledge base.

Despite these limitations, the current study expanded our knowledge of male survivors of CSA and mental health outcomes in middle and late adulthood. Consistent with complex trauma theory (Herman, 1992; Van der Kolk, 1996), CSA and childhood adversities were related to multiple psychological problems including depressive symptoms, somatic symptom severity, and hostility nearly fifty years, on average, after the sexual abuse occurred. Most of the previous research with male survivors has been based on relatively small, non-probability samples of college students or young adults. By utilizing data from a sixty year, panel cohort study, this investigation was able to expand the timeframe for examining long-term results with a population-based sample. As one of the first studies of its kind, the results illustrated the potentially harmful effects of CSA and childhood adversities that can last into late life for men, underscoring the need for timely assessment and treatment of this vulnerable, marginalized population.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03AG048768. The study also received financial support from the Boston College Institute on Aging (Aging Research Incentive Grant). The authors are grateful for the advice and assistance of Dr. Jan Greenberg (School of Social Work) and Dr. Jieun Song (Waisman Center) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Scott D. Easton, School of Social Work, Boston College, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, McGuinn Hall, Room 207, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, 02467, USA.

Jooyoung Kong, Center for Healthy Aging, College of Health and Human Development, Pennsylvania State University, 422 Biobehavioral Health Building, University Park, PA 16802, jzk255@psu.edu.

References

- Alfred GC, Hammer JH, Good GE. Male student veterans: Hardiness, psychological well-being, and masculine norms. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2014;15(1):95–99. doi: 10.1037/a0031450. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Author; Arlington, VA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bolen RM. Child sexual abuse: Its scope and our failure. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Spinazzola J. Phenomenology and psychological assessment of complex posttraumatic states. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18(5):401–412. doi: 10.1002/jts.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunevicius A, Rubinow DR, Calhoun A, Leserman J, Richardson E, Rozanski K, Girdler SS. The association of migraine with menstrually related mood disorders and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Women's Health. 2013;22(10):871–876. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4279. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A, Miller D. Robust inference with clustered data. In: Ullah A, Giles EA, editors. Handbook of empirical economics and finance. Chapman & Hall/CRC.; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. 2014 May 14; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34(6):454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Maercker A. Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2013;4(1-12) doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, Mazza D, Loxton D. Childhood sexual abuse and its association with adult physical and mental health results from a national cohort of young Australian women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30(11):1929–1944. doi: 10.1177/0886260514555270. doi: 10.1177/0886260514555270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Therapy, Research, Practice and Training. 2004;41(4):412–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412. [Google Scholar]

- Cutajar MC, Mullen PE, Ogloff JR, Thomas SD, Wells DL, Spataro J. Psychopathology in a large cohort of sexually abused children followed up to 43 years. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34(11):813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.004. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27(6):625–639. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00105-4. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28(7):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD. Understanding adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and their relationship to adult stress among male survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2012;40:291–303. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.707446. doi:10.1080/10852352.2012.707446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD. Disclosure of child sexual abuse among adult male survivors. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;41:344–355. doi:10.1007/s10615-012-0420-3. [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD. Masculine norms, disclosure, and childhood adversities predict long-term mental distress among men with histories of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38(2):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.020. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD, Renner LM, O'Leary P. Suicide attempts among men with histories of child sexual abuse: Examining abuse severity, mental health, and masculine norms. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.007. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton SD, Saltzman L, Willis D. “Would you tell under circumstances like that?”: Barriers to disclosure of child sexual abuse for men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2014;15(4):460. doi: 10.1037/a0034223. [Google Scholar]

- Fater K, Mullaney JA. The lived experience of adult male survivors who allege childhood sexual abuse by clergy. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21(3):281–295. doi: 10.1080/016128400248095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37(9):664–674. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.013. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Courtois CA. Defining and understanding complex trauma and complex traumatic stress disorders. In: Courtois CA, Ford JD, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. Gilford Press; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haringsma R, Engels GI, Beekman ATF, Spinhoven P. The criterian validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of self-referred elders with depressive symptomatology. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19:558–563. doi: 10.1002/gps.1130. doi: 10.1002/gps.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Roan CL. The class of 1957 in their mid-60s: A first look (Working Paper No. 2006-3) University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for Demography and Ecology; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd P, Carr D, Roan C. Cohort profile: Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS). International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;43(1):34–41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys194. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL. Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence from domestic violence to political terrorism. Guildford Press; New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual abuse of boys: Definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis KA, Chandler GE. Adverse childhood experiences: towards a clear conceptual meaning. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(7):1489–1501. doi: 10.1111/jan.12329. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spizer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating somatic symptom severity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:258–266. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Wimer DJ, Williams CSD. The relationships between masculinity variables, health risk behaviors and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. International Journal of Men's Health. 2009;8:3–21. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0801.3. [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D. The psychological impact of sexual abuse: Content analysis of interviews with male survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(4):525–548. doi: 10.1007/BF02103005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Rochlen AB. Men's likely responses to clinical depression: What are they and do masculinity norms predict them? Sex Roles. 2006;55(9-10):659–667. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9121-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RPJ, Gottfried M, Freitas G. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2003;4(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: A systematic review of reviews. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(7):647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(5):753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Baldwin N, Taylor J. Mental health problems and medically unexplained physical symptoms in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An integrative literature review. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing. 2012;19(3):211–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01772.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary PJ, Barber J. Gender differences in silencing following childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2008;17:133–143. doi: 10.1080/10538710801916416. doi:10.1080/10538710801916416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne JW. Best practices in quantitative methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Song J, Greenberg J, Hong J. Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2011;116(6):479–499. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.6.479. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.6.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S, Bender SS. Deep and almost unbearable suffering: consequences of childhood sexual abuse for men's health and well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2012;26(4):688–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00981.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Floyd FJ, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Hong J. Long-term effects of child death on parents’ health-related quality of life: A dyadic analysis. Family Relations. 2010;59:269–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00601.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataro J, Moss SA, Wells DL. Child sexual abuse: A reality for both sexes. Australian Psychologist. 2001;36(3):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, Wells DL, Moss SA. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184(5):416–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Granenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(2):79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, DiLillo D, Walsh K, Polusny MA. Pathways from child sexual abuse to adult depression: The role of parental socialization of emotions and alexithymia. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1(2):121–135. doi: 10.1037/a0022469. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA. The complexity of adaptation to trauma: Self-regulation, stimulus discrimination, and characterological development. In: Van der Kolk BA, McFarlane A, Weisaeth L, editors. Traumatic Stress. Guildford Press; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 182–213. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, Spinazzola J. Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18(5):389–399. doi: 10.1002/jts.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Owen J, Shea M. A latent class regression analysis of men's conformity to masculine norms and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(1):176–183. doi: 10.1037/a0026206. doi: 10.1037/a0026206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]