Abstract

The review is aimed at describing modern approaches to detection as well as precision and personalized treatment of ovarian cancer. Modern methods and future directions of nanotechnology-based targeted and personalized therapy are discussed.

Keywords: Genetic profiling, targeted therapy, nanotechnology, personalized medicine, siRNA

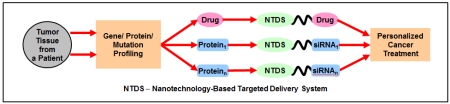

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most deadly malignancies that can form in the female body. Current statistical analysis reveals ovarian cancer as the 5th leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide [1]. It is also labeled as the most prevalent and lethal gynecologic cancer as well [2]. As a result, considerable research efforts have been dedicated to understanding ovarian cancer mechanisms and various methods for possibly treating the disease. Unfortunately, there has been little progress transitioning the research into effective clinical applications. Only 20% of the new cases of ovarian cancer are detected in an early stage and 5-year survival rates for patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer is roughly 30% [3]. Therefore, additional translational research must be carried out in order to progress the current state of clinical care of ovarian cancer.

For many years, scientists researched cancer in a reductionist approach, examining single targets or pathways. Years of researching various cancers with this approach have made many great improvements in the field of oncology, but it appears there is a limit to its efficacy, especially in improving patient mortality from ovarian cancer. In recent times, it has become evident that cancer is a disease driven by multiple cellular pathways, which can be affected in any number of ways [4]. Morphological and molecular studies investigating ovarian cancer make it clear that it should not be classified as a single disease, but a collection of disease subtypes with altering origins and significantly different clinical behaviors [5, 6]. In addition, tumors often have heterogeneous cell populations, comprised of various differentiated cell types, which form a unique microenvironment [7]. Therefore, new approaches to cancer medicine are required in order to improve treatment outcomes. The concept of systems biology has been brought up over the past few years and applied to cancer in efforts of developing so-called predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory (P4) cancer medicine. [8].

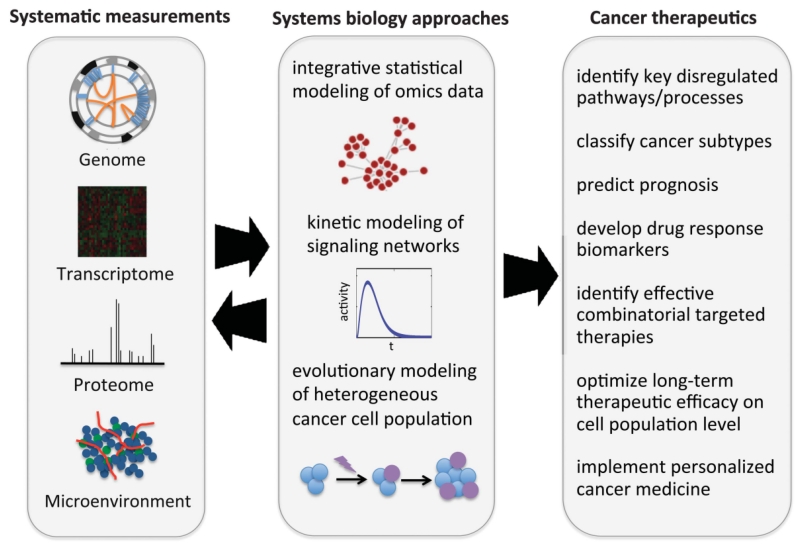

Systems biology takes a broader, more holistic approach to understanding the basic biology of cancer (Figure 1) [9]. It takes into account the various biological scales (genetics, signaling pathways, etc.) and their interaction to form the complex biological system found in a tumor [10-12]. The main objective of cancer systems biology is essentially to develop personalized cancer medicine. In order to achieve this, data on the different biological scales must be integrated for a more detailed picture of tumorigenesis, cancer stratification, and progression (Figure 2) [9]. Various models can also be designed in order to detect, diagnose, and predict the outcome of particular treatment [13-15].

Figure 1.

Systems biology approaches in cancer therapy. Reproduced with permission from [9].

Figure 2.

An integrative, iterative and model-based strategy for personalized cancer medicine. After initial diagnosis, a series of molecular profiling measurements are carried out for the patient for extensive characterization of the individual cancer. The results of the profiling are used to build computational. Based on the results of the measurements and modeling, an optimal therapeutic strategy is developed and applied for the specific patient. The process can be repeated during the treatment in order to account for possible cancer adaptation to therapy. Reproduced with permission from [9].

The present review will discuss advancements made in various fields of research that can be applied to personalized ovarian cancer medicine. It will emphasize different technologies developed over the years and their applications to personalize care of ovarian cancer patients in the clinic.

2. Emerging Technology for Precise Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer

The field of oncology has always been an ever-expanding area of medical care due to the massive investments and advances in the basic sciences. New developments in various fields of research have uncovered many aspects of the disease with an extreme emphasis on the complexity and high variability it can have in different patients. Consequently, the idea of a treating all forms of cancer with a single “miracle” treatment finally appears impossible. By integrating knowledge obtained from different research disciplines, models and algorithms could be generated to guide oncologists to optimize treatment regimens for patients based on the individual properties of their cancer.

2.1. Genetics

The genetics of humans essentially defines their individual peculiarities. Subtle differences found in the genetic makeup of a population create the different traits observed in society. In addition, variations in a gene among a population produce different gene isoforms that may result in altered gene function creating phenotypic variations in cell behavior. Unfortunately, some inherited gene isoforms can result in a diseased state of an individual. These are typically referred to as mutated genes. In the case of ovarian cancer, mutated genes inherited from a parent can make a person more susceptible to developing the disease in their lifetime.

However, inherited mutations only account for a small fraction of the overall cases of ovarian cancer detected. In 2015, there were an estimated 21,290 new cases of ovarian cancer, but it is believed that only 10-20% of these are attributed to germline mutations [16-18]. Either sporadic mutations or deregulated gene expression should be the major causes for most ovarian cancer patients. Recent advancements in genomics, transcriptome profiling, and epigenetic fingerprinting have been applied to cancer research and can possibly be integrated into a cancer systems biology approach for improving cancer medicine.

2.1.1. Genomic Sequencing Techniques

Since the completion of the human genome project, massive amounts of data have been uncovered about the relationship of many diseases and their relation to the genome. Perturbed signaling networks at the cellular level can alter cellular processes and cause symptoms of a diseased state exhibited at higher biological scales [8]. As mentioned earlier, cancer has an extremely complex etiology and during the development of the disease any number of mutations can occur. For this reason, genomic sequencing can be a valuable tool for oncologists. While genomic sequencing was expensive to perform during the human genome project, technological advancements in next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have reduced the cost of sequencing dramatically and have been applied to cancer research [19].

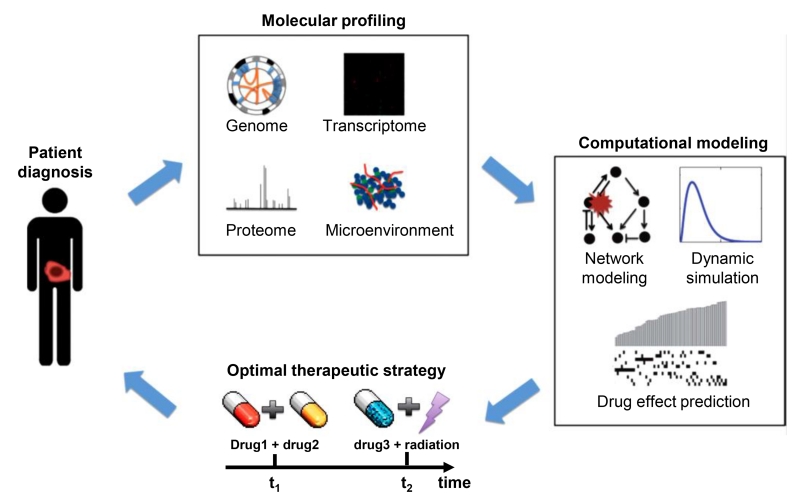

By performing genomic screening, it is possible to determine if a patient has any pre-existing factors that would make them more susceptible to develop cancer in their lifetime. For example, mutations found in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes increases a woman’s risk for developing ovarian cancer in her lifetime to roughly 40% and 18%, respectively [20-22]. For women without germline mutations, high throughput sequencing allows for screening population samples in a short amount of time and can possibly identify novel mutations in ovarian cancer. This technique has been applied extensively to breast cancer research and is starting to be applied to ovarian cancer as well [23]. Another technique known as mate-pair NGS has been shown to be useful for predicting disease progression in an individual (Figure 3) [24]. If genomic rearrangement were to occur during the progression of the disease, mate-pair NGS approaches like personalized analysis of rearranged ends (PARE) could be a method of detecting such parameters in patient samples [24].

Figure 3.

The PARE (personalized analysis of rearranged ends) approach. The method is based on novel mate-paired analysis of resected tumor DNA to identify individualized tumor-specific rearrangements. Such alterations are used to develop PCR-based quantitative analyses for personalized tumor monitoring of plasma samples or other bodily fluids. Modified from [24].

2.1.2. Transcriptome Profiling

For normal cell function, certain genes are expressed at definite levels to maintain regulation of the various processes occurring during the cell cycle. Alterations that may happen in the regulatory regions of a gene can lead to abnormal levels of its products, resulting in deregulation in normal cell processes. Usually such dysregulations result in one of two ways: cell death or neoplastic progression.

Screening a large population of tumor samples can help provide gene expression profiles that can be useful for stratifying various cancers into subtypes on a molecular level. Expression profiles from various populations can be integrated into various models to guide oncologists towards optimal patient management in the clinic [25]. Several methods have been optimized and are currently being applied to cancer research. One technique widely used today to obtain gene expression profiles is the quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Total RNA is extracted and purified from homogenized biopsy tissue, converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) by reverse transcription (RT), and is amplified by PCR. Unlike traditional PCR, this method employs fluorescent dyes to allow an instrument to detect RNA levels during the PCR process. This allows scientists to measure expression levels in the diseased state to diagnose patient samples with precision in relatively short periods of time [26-28].

Another popular method for transcriptome profiling is microarray assays. Microarray analysis requires isolating the total RNA in a sample and converting it into cDNA just like when performing qRT-PCR. However, microarrays rely on in situ hybridization of complementary nucleotide strands instead of sample amplification. DNA spots are placed on the microarray surface and each spot contains a custom designed DNA sequence that acts as a probe for specific gene detection. The sample cDNA is fluorescently labeled and when they bind to their complementary spots on the microarray, a fluorescent signal is emitted based on the amount of cDNA bound to the probe DNA. Microarray assays can be performed in a quick and cost-effective manner, which make them a promising tool for clinical transcriptome profiling of patient tumor biopsies. Plus, a number of studies have been conducted using microarray analysis for various types of cancers that have shown their high potential to screen patient samples for unique subtype-specific gene signatures that can help to predict treatment response, tumor progression, and patient prognosis [25, 30]. Meta-analysis of transcriptome profiles can aid in patient care and allow for optimal treatment courses (Figure 4) [25].

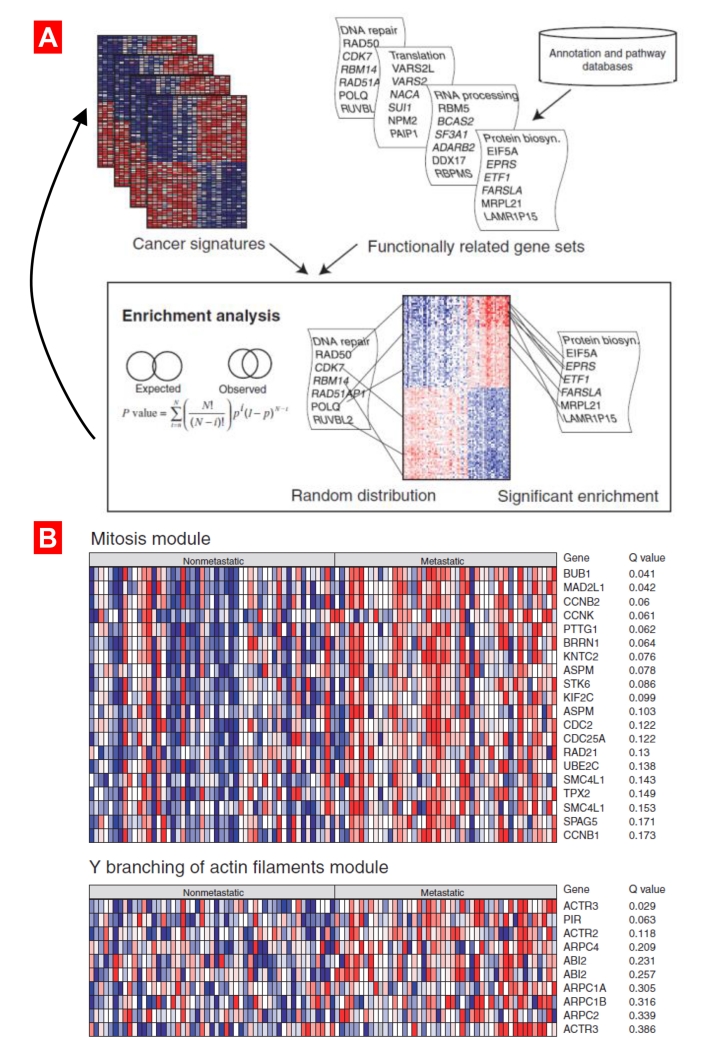

Figure 4.

Different analytical methodologies that have been used to build functional modules or enriched gene sets. (A) The binomial distribution was used to calculate the chance probability that a gene set would show a given degree of enrichment in a cancer signature. Gene set enrichment scores were computed for several types of gene sets (Gene Ontology, KEGG, Biocarta) across hundreds of cancer signatures from the Oncomine database. (B). Two functional modules (mitosis and the Y branching of actin filaments modules) enriched in a metastatic breast cancer signature. The modules showed significant enrichment, suggesting that these processes are important for the development of metastases in breast cancer. Modified from [25].

2.1.3. Epigenetic Fingerprinting

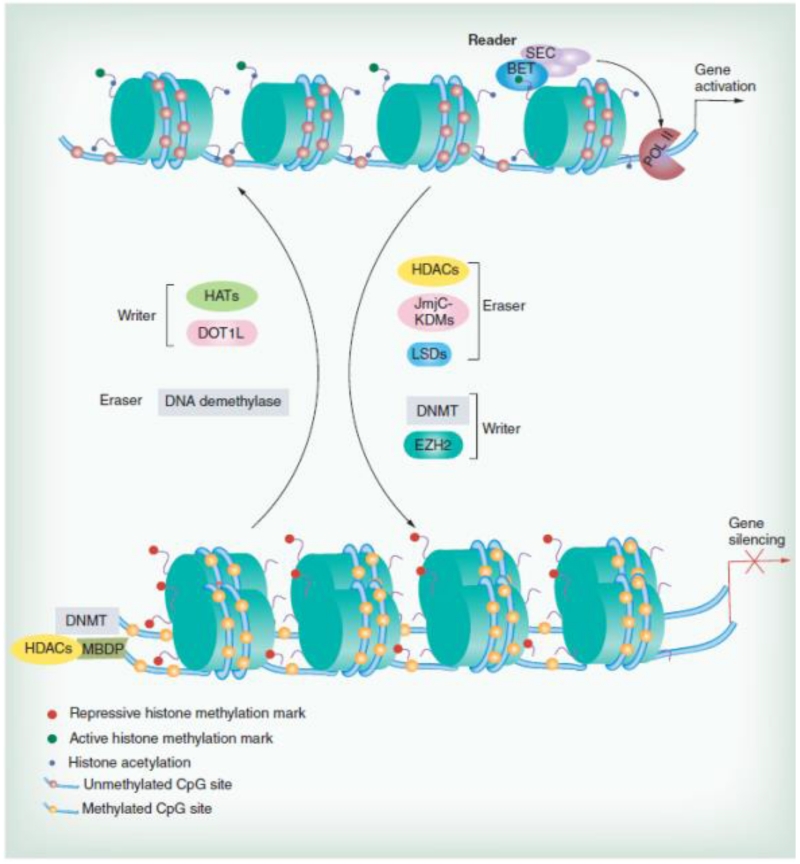

Many years of molecular biology research has determined that reversible alterations (known as epigenetics) that affect gene expression can be made to the genome. Epigenetic alterations to the genome occur during normal cell cycle regulation (Figure 5) [29]. More importantly though, research has shown these alterations tend to occur more frequently than mutations. Epigenetic alterations may represent one of the reasons why mutational analysis has been successful for guiding treatment decisions for only small subsets of patients [31]. There are two major forms of epigenetic regulation: one that occurs at the gene level and a second that occurs at the chromosomal level. The first is known as genomic methylation. Methyl groups can be added to certain regions of genes, which can either active or inactive gene expression. Promoter region methylation will repress gene expression, while methylation in the body of the gene is observed in actively expressed genes [32]. Modifying histone tails is the other major method used by cells to regulate their gene expression levels. Acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitination of histone groups can alter gene expression by changing the packing density of the chromatid and altering mRNA splicing patterns [33, 34]. Epigenetic changes can serve as possible biomarkers for early tumor detection. Epigenetic profiles obtained for patient samples can augment mutational data for even more accurate tumor diagnosis and prognosis [35].

Figure 5.

The epigenetic transcriptional machinery. BET, SEC: representative reader (proteins that bind modifications and facilitate epigenetic effects); HATs, DOT1L, DNMT, EZH2: representative writers (enzymes that establish DNA methylation or histone modifications); histone deacetylases, JmjC–KDMs, LSDs, DNA demethylase: representative erasers (proteins that remove DNA methylation or histone modification marks). Reproduced with permission from [29].

Epigenetic fingerprint profiling can help in determining how epigenetic regulation affects gene expression and in the case with ovarian cancer, it may be possible to find therapeutic targets and determine the disease progression [36].

2.1.4. Recent Advanced Technologies for Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis, Imaging and Surgery

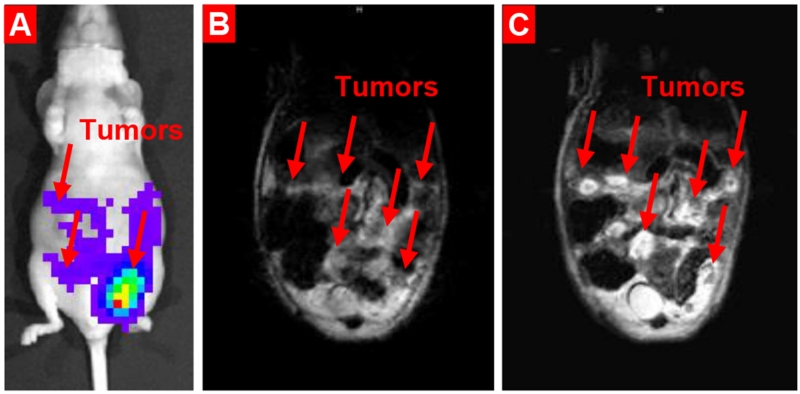

Several recent studies have been carried out in order to provide for an integrated proteogenomic characterization of ovarian cancer. These investigations combine genomics, transcription, proteomics and phosphoproteomics data in order to identify the molecular components and underlying mechanisms associated with ovarian cancer and specifically with short overall survival of patients. Recently, investigators from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory performed a comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteomic characterization of 174 ovarian tumors [37]. The integration of genomic data with proteomic measurements revealed a number of mechanisms and proteins (e.g. copy-number alternations, proteins associated with chromosomal instability, signaling pathways that diverse genome rearrangement, etc.) that allowed for stratifying patients for therapy and predicting clinical outcomes in high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC). However, despite of the remarkable advances in screening technologies, the most HGSC cases are still detected in advanced stages when the efficacy of the treatment and available therapeutic options are limited. The development of efficient and sensitive imaging techniques and screening protocols for the detection of the disease in early stage is extremely important. Currently, several imaging techniques are being used for early detection of HGSC. In addition to established methods including serum CA-125, ultrasound, sonography, CT, and MRI scans, innovative in vivo confocal microlaparoscopic procedure, transvaginal sonography (especially enhanced transvaginal sonography and transvaginal color Doppler sonography), photoacoustic and tumor-specific fluorescence imaging have been recently investigated [38]. Such techniques allow for gathering information regarding the size, composition, and location of the tumor as well as detection of metastases. In turn, such information is important for determining the stage of the disease and selecting treatment plans. Confocal microlaparoscopes are also able to display live images of abnormal regions in real-time during surgery and guiding biopsies. Nanotechnology has an ability of enhancing the existing imaging techniques as well as developing novel approaches for tumor-specific imaging that also can be applied to ovarian cancer. For instance, single-walled carbon nanotubes have been proposed for in vivo fluorescence imaging [39] as well as tumor-targeted responsive nanoparticle-based systems were recently developed for enhancing magnetic resonance imaging and simultaneous therapy of ovarian cancer [40, 41]. It was shown that uniform, stable cancer targeted nanoparticles (PEGylated water-soluble manganese oxide nanoparticles, modified with LHRH targeting peptide) demonstrated a remarkable capability of substantially enhancing the detection of ovarian tumor and intraperitoneal metastases (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Enhancement in ovarian cancer MRI sensitivity and specificity by ovarian cancer-targeted Mn3O4 nanoparticles. (A) Representative bioluminescence IVIS optical imaging. (B-C) Representative magnetic resonance imaging. (B) MRI without a contrast agent. (C) MRI after injection of biocompatible cancer-targeted Mn3O4 nanoparticles. Modified from [41].

2.2. Proteomics

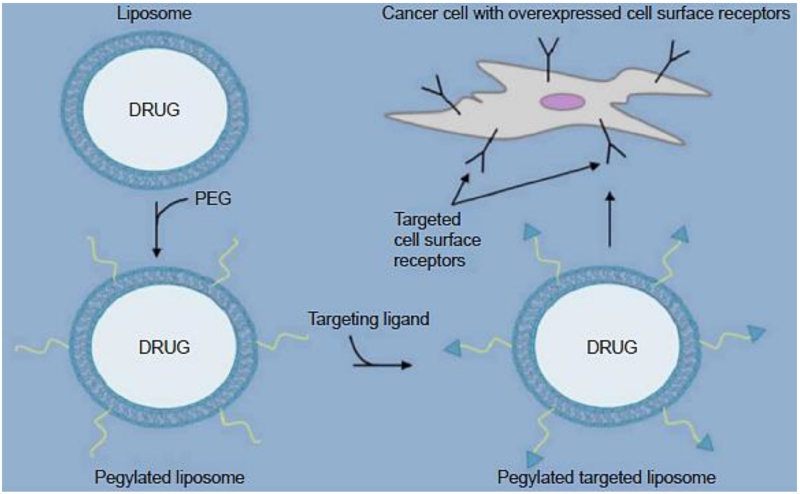

Proteins are major components involved in carrying out the functions of cellular pathways. Therefore, understanding the structures and functions of proteins is essential for understanding how they may play a role in certain diseases. Proteins can serve as biomarkers for diagnosing cancers. A recently developed targeted proteomics technique called selected reaction monitoring (SRM) has been proven to be efficient at quantifying protein biomarkers in patient tissues and blood samples [42]. This could be a possible technique for early cancer diagnosing, if viable biomarkers are identified and can be used in the clinic. At the same time, detected proteins can be used as possible therapeutic targets in cancer medicine. Cell protein receptors overexpressed in cancers could be targeted either to deliver a chemotherapeutic directly specifically to the tumor or as a therapeutic target itself for higher treatment efficacy (Figure 7) [43, 44].

Figure 7.

Receptor targeted drug loaded liposomes. Targeted Targeting ligands coupled to the distal end of poly(ethylene glycol), which are anchored to the liposome surface in order to generate a targeted PEGylated liposome system specific to upregulated cell surface receptors. Reproduced with permission from [44].

2.3. Single-Cell Analytics

One of the major challenges facing oncologists that impedes optimal cancer treatment is the fact that tumors are heterogeneous and contain a number of distinct cell types (Figure 8) [7]. In order to effectively treat cancer, so-called cancer stem cells which initiate tumor growth and reoccurrence need to be targeted. However, studies determined that cancer stems cells generally make up roughly 1% of the cell population in a tumor [45-47]. Consequently, performing molecular analytics on a homogenized patient biopsy may not give an accurate depiction of the underlying mechanisms that drove cancer formation. As the disease progresses, the stem cells differentiate into different cells types that usually have varying gene and protein expression profiles. This means that the use of homogenized tissues from whole biopsies for determining an expression profile can result in signal to noise complications leading to inaccurate diagnosis of patient tumors [48]. This enormous amount of heterogeneity also makes it difficult to distinguish subtype stratification from cancer progression [49].

Figure 8.

Development of cancer in a complex and dynamic tumor microenvironment (TME). Cancer cells are in close relationship with diverse non-cancer cell types within the TME, forming a functional nexus that facilitates tumor initiation, survival, and exacerbation. Cytotoxicity generated by treatments including chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapy eliminates many malignant cells within the cancer cell population; however, surviving cells are frequently retained in specific TME niches. Reproduced with permission from [7].

In recent years, several researchers have adopted the concept of microfluidics as a method for performing single-cell analytics. These methods have been proven useful for sorting single cells based on certain properties [50, 51]. Once the cancer stem cells have been isolated, they can accurately be analyzed to determine what pathways have been disturbed and drive the disease. Single-cell analytical technologies have been emerging throughout the years and show good promise clinical application.

Several whole-genome amplification (WGA) methods have been designed to accurately amplify and detect small amounts of DNA. Single-nucleus sequencing (SNS) is an amplification method that uses degenerate-oligonucleotide PCR to amply DNA from a single cell. It shows low coverage of the entire genome, but has been proven useful for determining the copy number of particular genes [52]. Another WGA method gaining momentum is multiple displacement amplification (MDA). Random primers are used during the amplification process allowing for a linear amplification. MDA generates long DNA products and shows high genome coverage, which makes it useful for screening genes for point mutations and identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) relevant to clinical application [53-55].

Moreover, transcriptome analysis, as mentioned earlier, is essential for examining the driving forces of a cancer. Just like with genomics, multiple methods have been optimized to analyze the transcriptomes of single cells. Single-cell mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) is a promising method for single cell analysis. This method utilizes multiplexed reverse transcription and PCR to amplify specific targets in a simple one-step protocol, which allows for high-throughput. Unfortunately, this method is currently limited to analyzing a small number of genes [56, 57]. Another method for analyzing single-cell transcriptomes is SMART-seq® amplification (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA). The protocol for this method involves template-switching. This includes anchoring a primer site onto the 3’ end of cDNA fragments. The cDNA is amplified using traditional end-point PCR and the amplified sample is sequenced by sequencers. This method can identify SNPs in transcripts and different isoforms produced during transcript maturation. However, it has shown limited success in profiling certain transcripts that are expressed at low levels [58, 59]. Both of these techniques shown promise in a laboratory setting, but seem like have a limited application in the clinic since each sample is handled and analyzed separately, limiting the amount of throughput and slowing down the entire diagnostic process. As a result, high-throughput techniques such as molecular barcoding of single cell transcripts in reaction wells or droplets prior to generating a transcript sequence libraries were developed [60]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing (CEL-seq) utilizes this approach by depositing single cells along with barcode transcript probes into microwells. The labeled transcripts are converted to cDNA and can be selectively amplified based on the barcode labels [61]. Drop-seq is a method that separates cells into microdroplets, where barcodes are added and associate with specific RNA transcripts. All of the barcode-associated transcripts can be amplified and sequenced in parallel to generate multiple sequence libraries in a short amount of time [62]. The barcoding strategy utilized by both methods enables high-throughput analysis of single-cell transcriptomes and seems like it is promising for clinical application [63].

Proteomic analysis of single cells is much more challenging compared to genomic and transcriptomic analysis due to the fact that proteins cannot be amplified by any technology currently available [60]. Mass cytometry is one method that labels proteins with isotope-bound antibodies, which can be analyzed using multiplexed fluorescence microscopy. It can help to quantify proteins in order to generate proteomic profiles for patients [64]. Multiplexed ion beam imaging (MIBI) can quantify proteins in single cells to produce proteomic profiles similarly to mass cytometry. MIBI differs slightly by using secondary-ion mass spectrometry to image proteins labeled by isotope-tagged antibodies [65]. Both of these methods have shown a substantial potential for studying basic cell processes like cell-signaling pathways and possibly can be applied to the clinical oncology.

3. Clinical Application of Precision Ovarian Cancer Medicine

3.1. Biomarkers for Earlier Detection of Ovarian Cancer

Most patients with ovarian cancer do not demonstrate symptoms until the disease has progressed into an advanced stage [66]. A method for screening for earlier detection of ovarian cancer in patients seems to be imperative. An ideal biomarker can be DNA, RNA, or a protein that is tumor specific and is released into bodily fluids like the blood [67-70]. Several viable biomarkers have been identified for a few forms of cancer. However, ovarian cancer is lacking strong biomarkers that correlate with ovarian tumor formation and progression. One candidate biomarker is the CA-125 glycoprotein. Many reports have been published stating that a number of patients with ovarian cancer exhibit elevated levels of CA-125. Actually, some reports show that up to 78% of patients with ovarian cancer have elevated levels of this glycoprotein [71, 72]. Since such a staggering number of patients have this commonality, screening for CA-125 levels in women has been proposed for detecting ovarian cancer while patients are presymptomatic. However, the validity of CA-125 as a biomarker for detecting ovarian cancer is questionable. CA-125 levels can become elevated due to inflammation, cirrhosis, and diabetes mellitus [73]. There is also increasing evidence that shows that CA-125 is sometime elevated in other cancer like endometrial, fallopian, and lung cancers [74]. False positive results represent therefore a substantial obstacle for this test. Other biomarkers are required to further confirm whether elevated levels of CA-125 observed in a patient are due to ovarian cancer or another condition.

3.2. Targeted Therapeutics

The debulking surgery is still necessary for many advanced ovarian patients [76]. However, micronodular and floating tumor colonies, which are spread within the peritoneal cavity, cannot be adequately treated by surgery or radiation and require extensive chemotherapy. Current maintenance chemotherapies including olaparib and bevacizumab delay disease progression, but do not prevent recurrence or death. The recent combination treatment hold promise for the targeted chemotherapeutics [77]. The concept of personalized medicine relies on treatments that can be applied to specific subtypes of ovarian cancer seen throughout the patient population. Targeted therapy utilizes the molecular profile of a patient’s cancer to design a more efficacious plan for treating the disease. Defined biomarkers can be targeted to create an antitumor response or as a mechanism for tumor-specific delivery of certain traditional chemotherapeutic drugs (Figure 9) [75]. The following targeted therapies have been studied extensively and are used clinically to treat certain subtypes of ovarian cancer.

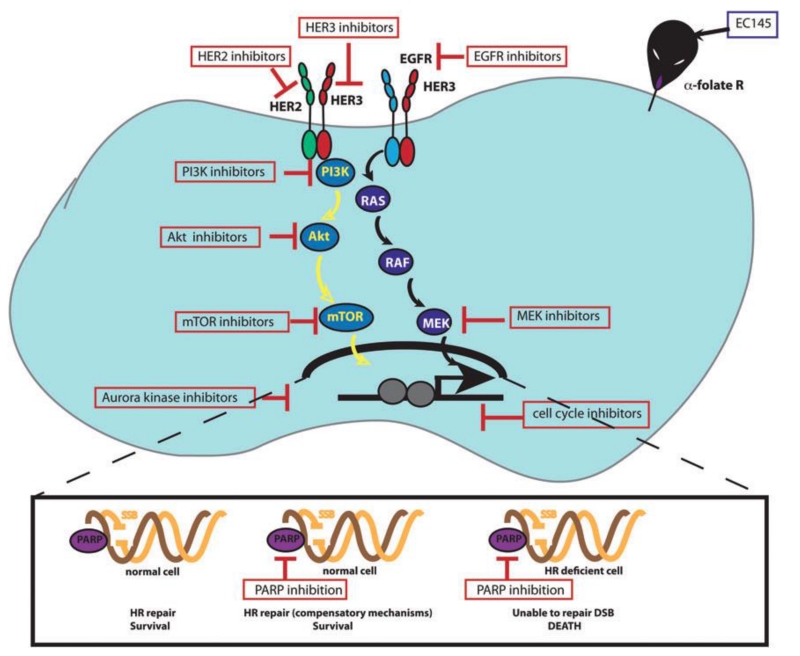

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram illustrating core molecular pathways driving ovarian cancer that represent therapeutic targets. Reproduced with permission from [75].

3.2.1. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

Anti-angiogenic therapies have been one of the most successful classes of targeted therapeutics in the clinic for ovarian cancer perhaps due to the fact that most cases of ovarian cancer are detected at more advanced stages. Angiogenesis has long been known to play a key role in tumor growth, disease progression, and has been considered a possible therapeutic target of tumors since the 1970’s [78]. Therapeutics inhibiting this process may slow cancer growth and progression, which appears to make certain subtypes of ovarian cancer more susceptible to traditional chemotherapies [79].

A major component in angiogenesis is VEGF, an endogenous compound that promotes tissue vascularization [80, 81]. Studies have shown it is overexpressed in a subset of patients that have poor prognosis compared with patients with normal levels of the compound [82, 83]. To exploit this feature in certain patients, Roche developed bevacizumab (sold under the trade name Avastin®), a humanized monoclonal antibody (MAB) that binds to VEGF and inhibits the compound’s ability to bind to it receptor [84, 85]. Therefore, VEGF cannot elicit the activation of any downstream signaling effects. This tends to reduce vascularization and normalizes the tumor microenvironment, but does not typically show cytotoxic effects [85]. For this reason, bevacizumab has been studied as a combinational therapy administered with several cytotoxic cancer therapeutic drugs for first-line recurrent ovarian cancer therapy.

Two phase III clinical trials, the international collaboration on ovarian neoplasms 7 (ICON-7) and gynecologic oncology group study 218 (GOG218), were conducted recently to evaluate the effects of two combinational therapies involving bevacizumab combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel [86, 87]. The ICON-7 study enrolled a total of 1873 women, who were either given carboplatin and paclitaxel with bevacizumab or a placebo to investigate if the addition of bevacizumab could increase progression-free survival (PFS) in the patients with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian cancer. The study observed a prolonged median PFS in the groups receiving bevacizumab compared to the control group and concluded the use of bevacizumab as a first-line therapy, in combination carboplatin and paclitaxel, as well as a maintenance monotherapy could increase PFS in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer [86]. The GOG218 study was a complementary study to ICON-7. It enrolled 1528 women with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian cancer and these patients were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel combined with either bevacizumab or a placebo to investigate PFS and interim overall survival of the patients. The study showed improved median PFS and overall survival in patients receiving bevacizumab and concluded the addition of bevacizumab could be an approach to treating advance-staged epithelial ovarian cancers [87].

A phase III ovarian cancer study comparing efficacy and safety of chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy in platinum-sensitive recurrent disease (OCEANS) for recurrent ovarian cancer was conducted to investigate a combinational therapy of bevacizumab combined with carboplatin and gemcitabine and evaluate whether the addition of bevacizumab can increase PFS in patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian tumors. There was a significant improvement in the median PFS among the patients that received the addition of bevacizumab to the therapeutic regime. Patients receiving bevacizumab had a median PFS of 12.4 months compared to the median PFS 8.4 months observed among the patients who only received carboplatin and gemcitabine [88]. The results showed promise, but the third interim overall survival (OS) analysis conducted in the study did not show any significant improvements to patient OS with the addition of bevacizumab [89]. The AURELIA (avastin use in platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer) study, a recent phase III trial for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer evaluated combinational therapies involving bevacizumab combined with paclitaxel, topotecan, or liposomal doxorubicin. The addition of bevacizumab showed and improved median PFS compared to each therapeutic agent administered without bevacizumab [90]. The median patient OS was 16.6 months for patients that received chemotherapy, combined with bevacizumab and 13.3 months for the patients that received only chemotherapy [91].

Bevacizumab is not currently approved for first-line or maintenance therapy of ovarian cancer by the FDA, but has been approved as a first-line therapeutic agent, when combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel, for treating advanced-stage ovarian cancer by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [84]. Perhaps if more clinical studies are conducted that show the therapeutic benefits of supplementing chemotherapy with bevacizumab, the FDA would reconsider approving it for the treatment of certain ovarian cancers. Nevertheless, VEGF and its receptor are prospective targets for certain cancers and could be exploited as such. More research is required for anti-VEG inhibitors and investigating their true potential in ovarian cancer therapy.

3.2.2. Angiokinase Inhibitors

Angiogenesis involves multiple signaling pathways, which require a number of tyrosine kinases to activate the signal cascade. Therefore, inhibiting tyrosine kinases other than the VEGF receptors become a promising concept for treating ovarian cancer. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are generally referred to as orally bioavailable small molecules that can inhibit multiple tyrosine kinases with high potency [92, 93]. Molecules that target tyrosine kinases involved in angiogenesis are also commonly referred to as angiokinase inhibitors [94].

Pazopanib (GlaxoSmithKline) is a angiokinase inhibitor that targets VEGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and c-kit [95]. A phase III trial (AGO-OVAR 16) was conducted to investigate pazopanib as first-line and maintenance therapies epithelial ovarian cancer [96]. Pazopanib was compared with a placebo to evaluate progression-free survival (PFS) in both groups. The group treated with pazopanib has a median PFS of 17.9 months compared to 12.3 months seen in the placebo group [97]. Another tyrosine kinase inhibitor called nintedanib (Boehringer Ingelheim) has been investigated as first-line and maintenance combinational therapies with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The study is ongoing and results are expected in 2016 [98]. A third tyrosine kinase inhibitor called cediranib (AstraZeneca) was recently investigated in the double blind ICON6 study as a combinational first-line therapy with platinum-based chemotherapeutics and a maintenance monotherapy. The study investigated the efficacy of cediranib, while also evaluating toxicity, PFS, quality of life (QOL), and OS [99]. The median PFS increased by 3.2 months when comparing the treatment group with the control group [100]. Overall, angiokinase inhibition appears to be a promising approach to treating ovarian cancer. The molecules mentioned above have good overall patient response rates when administered alone or as a part of a combinational therapy.

3.2.3. Poly-ADP Ribose Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitors

Base excision repair is a DNA repair pathway for fixing single-stranded breaks in which PARP enzymes play a key role. When PARP inhibition occurs, the single-stranded breaks in the DNA eventually collapse and form double-stranded breaks during replication [101, 102]. Double-stranded breaks in DNA are repaired by homologous recombination, a process mediated by the BRCA enzymes, or by non-homologous end joining, an error prone repair mechanism that usually leads to genetic instability. PARP inhibition in individuals with BRCA-deficiencies only allows for double-stranded breaks to be repaired by non-homologous end joining, which usually results in cell death [103-105]. Ovarian cancer patients with BRCA mutations are a subset of patients whom would benefit the most from PARP inhibition therapy and a considerable amount of effort has been invested into the evaluation of the concept.

Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor (AstraZeneca) that has shown a promise for treating BRCA-deficient ovarian tumors in patients [106, 107]. It has been studied extensively as a monotherapy as well as in combination with various chemotherapeutic drugs traditionally used for ovarian cancer patients. A phase-II trial was conducted using olaparib as a maintenance therapy for patients that had recurrent ovarian cancer with or without BRCA 1/2 mutation. The Study concluded that individuals with BRCA mutation(s) exhibited a longer progression-free survival compared to individuals without the mutations [108, 109]. Due to the promising results for patients with BRCA-deficient tumors, the SOLO studies, two phase III trials are currently being conducted using olaparib as a maintenance monotherapy for patients that are known to have these mutations and have undergone platinum-based chemotherapy as a first-line treatment [110, 111]. Primary outcome measurements and analysis are expected in 2016.

Other PARP inhibitors are currently being studied as well. Rucaparib (Covis) is currently being investigated in a phase-II trail (ARIEL2) for platinum-sensitive, relapsed high-grade ovarian cancer. The study is currently recruiting participants and expects to obtain primary results in 2017 [112]. Veliparib (Abbot) is currently in a phase-II trial, evaluating patients with mutation in the BRCA 1 and/or 2 gene(s). Results for this study are expected in 2016 [113]. Niraparib (Tesaro) is currently being investigated in a phase III trial study as a maintenance therapy for patients with platinum-sensitive tumors either with or without BRCA 1 and/or 2 gene mutation(s). The study will determine the efficacy of niraparib as a maintenance monotherapy for patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Results are expected towards the end of 2016 [114].

Overall, the results emerging from clinical trials on PARP inhibitors demonstrate they might have a lot of potential treating various cancers. Patients with gynecologic cancers containing BRCA 1 and/or 2 mutation(s) appear to benefit the most from chemotherapy supplemented with a PARP inhibitor. Even still, PARP inhibitors are a relatively new class of anticancer agents and need to be investigated even further to determine their full potential. Also, further studies should be conducted to investigate any potential toxicity issues that may arise from interactions of the agents in combinational therapies including PARP inhibitors and conventional chemotherapies [84].

3.2.4. Folate and Folate Receptor Alpha (FRα) Antagonists

Folate and its respective receptors are essential components of cells that rapidly divide. Folate is important for DNA synthesis and helps promote cell division. Inhibiting folate synthesis represents therefore a potential method for slowing tumor growth and potentially cause cytotoxic effects in cancers that are highly dependent on folate metabolism for DNA replication during cell division [115]. Several folate metabolism inhibitors have been studied extensively to date. Aminopterin and its successor methotrexate are molecules that competitively compete with folate for the binding site of the dihydrofolate reductase enzyme [116]. Fluorouracil-5 is a pyrimidine analog that acts as a suicide inhibitor by irreversibly binding to the thymidylate synthase enzyme [117]. These drugs have been studied for treating various cancers, but have been shown some limited success partly due to toxicity and patient tolerance issues [118, 119].

However in recent years, other thymidylate synthase inhibitors called pemetrexed (Eli Lilly) and raltitrexed (AstraZeneca) have been investigated as potential antifolate therapies for ovarian cancer [120]. Pemetrexed, combined with bevacizumab, has been evaluated as a combinational therapy for ovarian cancer patients with recurrent tumors. Median patient PFS improved to 7.9 months and median OS increased to 25.7 months [121].

Targeting FRα seems to be another promising approach for treating ovarian cancer. Reports have shown that as high as 80% of epithelial ovarian cancers overexpress FRα, while the normal ovarian tissue in the same patient show extremely low levels of the expression [122, 123]. In addition, levels of FRα expression correlate with staging and determining the grade of ovarian cancer [124, 125]. This makes FRα a promising target for certain ovarian cancer patients. Farletuzumab (Morphotek) represents a fully humanized monoclonal antibody (MAB) that binds FRα, but does not inhibit folate metabolism. In fact, when farletuzumab binds FRα it promotes cell lysis by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) [126]. A phase II trial conducted with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian tumors evaluated farletuzumab combined with carboplatin and taxane followed by farletuzumab monotherapy for maintenance. The study concluded that the combinational therapy improved the overall tumor response rate and farletuzumab was well tolerated by patients [127]. However the phase III FAR-131 study, which investigated farletuzumab combined with carboplatin and taxane as a combinational therapy for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian tumors, failed to reach the primary PFS endpoint and raised concerns whether farletuzumab would be effective in the clinic [128]. Further testing may yield better results.

Folate-conjugated therapeutic agents are one more approach for exploiting ovarian tumors overexpressing FRα. The therapeutic agent relies on the folate molecule to target FRα in the tumor for increased tumor-specific drug disposition [129]. Vintafolide (Merck) is a folate molecule conjugated with desacetylvinlastine hydrazine, a highly potent vinca alkaloid [130]. Vinca alkaloids are a set of anti-mitotic alkaloid agents derived from plants belonging to the genus Vinca [131]. Vintafolide was investigated as a combinational therapy with PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) for recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian tumors in patients that have undergone less than three separate chemotherapeutic regimens in the phase II PRECEDENT study. The combinational therapy was compared with PLD as a monotherapy and the advantages of the combinational therapy were confirmed. Patients treated with PLD only had a median PFS of 2.7 months and patients treated with PLD and vintafolide had a median PFS of 5.0 months [132]. A phase III PROCEED study is currently underway and results are expected in 2016 [133].

In conclusion, therapies that disrupt folate metabolism appear like a possible approach to treating recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian tumors. Although, farletuzumab has shown promised results in phase II trials, but data from phase III trials did not confirm its clinical applicability. The real potential for exploiting the overexpressed FRα that is registered frequently in epithelial ovarian cancer cases appears to be with the folate-conjugates therapeutic agents. Targeting the folate receptor could be a possible approach to systematic treatment of ovarian cancers that may have already metastasized.

3.2.5. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (HER) Antagonists

The ERBB2 gene is a known proto-oncogene that encode for the human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2). It has been extensively studied in breast cancer and its overexpression correlates with poor prognosis [134]. HER2 generally has no correlation with the prognosis of ovarian cancer. It typically is never seen at elevated levels in most ovarian cancers, but is elevated in advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer patients in rare cases [135]. Consequently, it could potentially be a small subtype of ovarian cancer that could benefit from HER2 inhibition. Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) and pertuzumab humanized MABs (Roche) that have shown great efficacy treating HER2-positive breast cancers [136, 137]. No clinical evidence to date supports trastuzumab as a viable treatment for ovarian cancer [138]. Interestingly, pertuzumab does not show promise as a monotherapy, but might be useful in combination with other chemotherapeutic for treating platinum-resistant ovarian tumors [139]. In a phase II trial conducted on patients with platinum-resistant ovarian tumors, investigated the efficacy of a combinational therapy of containing pertuzumab and gemcitabine. Treatment response rate for patients that received the combinational therapy was 13.8%, a significant increase from the 4.6% response rate observed by the patients who received gemcitabine and a placebo [140]. An ongoing phase III study is currently being conducting on recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian tumors to investigate combinational therapies of pertuzumab or a placebo with gemcitabine, paclitaxel, or gemcitabine [141]. Results for this study are expected in 2016.

The promising outlook for pertuzumab is most likely due to its mechanism of action. The MAB binds to HER2 in a manner that inhibits its ability to dimerize with HER3 [142]. It is significant because HER3 overexpression has been associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer [143]. A HER3-targeted MAB named MM-121 (Merrimack Pharmaceuticals) is under current investigation as a combinational therapy with paclitaxel in a phase II study for platinum-resistant, advanced-stage ovarian tumors [144]. Finally, HER antagonist showed some promise and could be used as a targeted therapy for platinum-resistant tumors and for ovarian cancers that overexpress ERBB2 and/or ERBB3 genes.

3.2.6. Estrogen Receptor (ER) Antagonists

The estrogen receptor (ER) has been studied extensively in breast cancer. Evidence has revealed that estrogen influences increased proliferation in a subset of ovarian cancers [145]. In fact, it has been reported that up to 60% of patients with ovarian cancer are ER positive [146]. Tamoxifen has been investigated for treating recurrent ER-positive ovarian cancer tumors since it has had success treating ER positive breast cancers. However, a meta-analysis of 20 clinical trials shows a median overall patient response rate to tamoxifen therapy of only 13% [146]. A novel ER antagonist called fulvestrant (AstraZeneca) was investigated as monotherapy for recurrent ER-positive ovarian tumors in a phase II trial. Patients treated with fulvestrant showed a 38% overall response rate. The results from this study have warranted a phase III trial study to be conducted [147]. ER-positive ovarian tumors make up a decent subset of the overall cases seen. Therefore even though ER antagonists have had little success thus far, there could still be potential for this therapeutic approach. Perhaps a combinational therapy may be efficacious in treating ER-positive ovarian tumors.

3.2.7. Aromatase Inhibitors

Aromatase is also known as the estrogen synthase enzyme. As the name suggests, it plays a role in estrogen production and has been thought of as another approach to treating ER-positive tumors [148]. Anastrozole (AstraZeneca) is one aromatase inhibitor that has been studied for possible treatment for ER-positive ovarian tumors. It competes with various androgens for the aromatase-binding pocket, reversibly binding to inhibit the production of estrogen [149]. Letrozole (Novartis) is another aromatase inhibitor with the mechanism of action similar to anastrozole [150]. A third aromatase inhibitor called exemestane (Pfizer) has a different mode of action. It acts as a suicide inhibitor, binding to the active site of the enzyme, permanently inactivating it and inhibiting estrogen synthesis [151]. Exemestane has been investigated for treating refractory ovarian cancers [152]. A meta-analysis of nine clinical studies showed the three demonstrated about the same overall patient response rates with roughly 8% of the patients tested in all of the trials exhibiting a therapeutic response [146]. While this is not a pronounced value, there may be a potential future for aromatase inhibitors in combinational therapies with ER antagonists and/or chemotherapeutics.

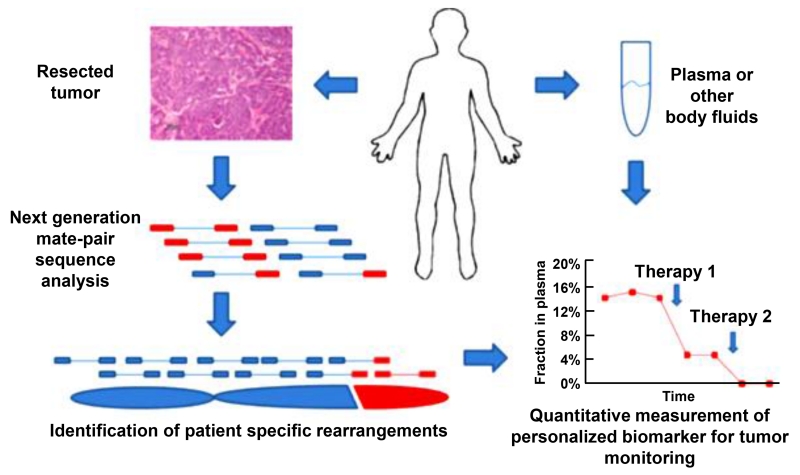

3.3. Nanotechnology Approach for Personalized Targeted Therapy of Ovarian Cancer

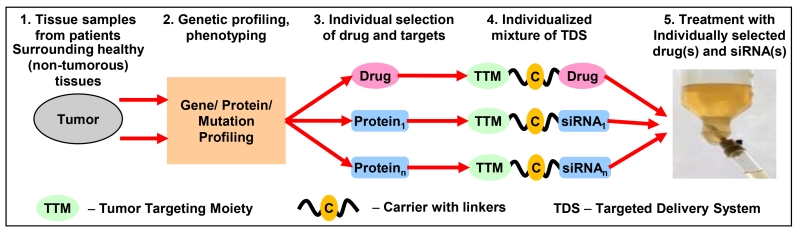

Recently, we proposed an innovative approach for targeted personalized treatment of different cancers that can also be successfully applied to ovarian cancer [153-155]. Based on the extensive preliminary data obtained in our laboratory, we concluded that for the effective suppression of the growth of ovarian tumor, an inducer(s) of cell death (anticancer drug(s)) should be delivered to the cancer cells simultaneously with the suppressors of multidrug resistance and cell death defensive mechanisms [153-165]. However, different proteins can be responsible for tumor progression, drug resistance and cell death defense in different patients. Consequently, during the personalized precision treatment of a particular patient with ovarian tumor, only those of such proteins that overexpressed in particular tumor tissues from a particular patient should be suppressed. We identified a set of targets that: (1) are responsible for multidrug resistance, tumor progression and anti-apoptotic cellular defense in ovarian cancer cells and (2) are most often overexpressed in patient tumor samples when compared with surrounding healthy ovarian tissues. Also, a set of nanotechnology-based targeted delivery systems (NTDSs) was synthesized. Each of NTDS contains only one protein inhibitor (siRNA) to suppress one targeted protein or an anticancer drug. These NTDSs can be used in any combination with each other. Each of these NTDSs also contains a tumor targeting moiety (a synthetic analog of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone, LHRH) that is used for the delivery of drugs and siRNA specifically to ovarian tumors and minimize adverse side effects. The proposed simplified treatment protocol looks as follows (Figure 10) [153]. Ovarian tumor tissue and surrounding normal tissue samples are taken from the patient. Total RNA from the samples is isolated and subjected to qRT-PCR using selected panel of primers. Based on the results of the measurements, the most overexpressed proteins are selected as targets for the personalized treatment. Corresponding NTDSs containing anticancer drug(s) and targeted siRNAs are selected, mixed and used for the treatment. Preliminary in vitro and in vivo data showed that such a personalized treatment approach is much more effective when compared with a standard treatment protocol.

Figure 10.

Personalized cancer treatment. Modified from [153].

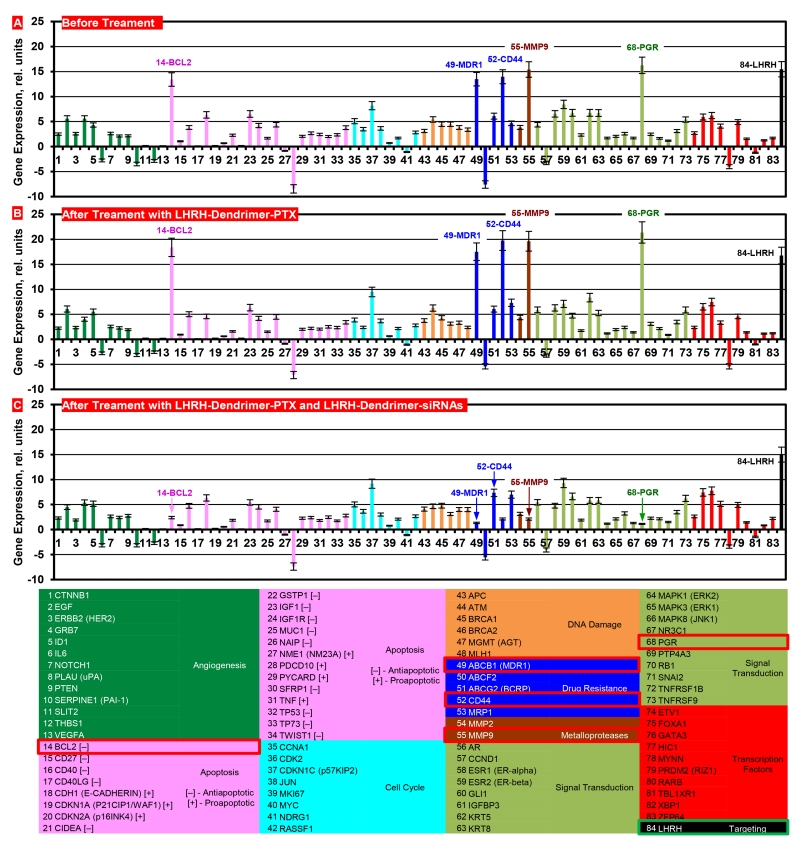

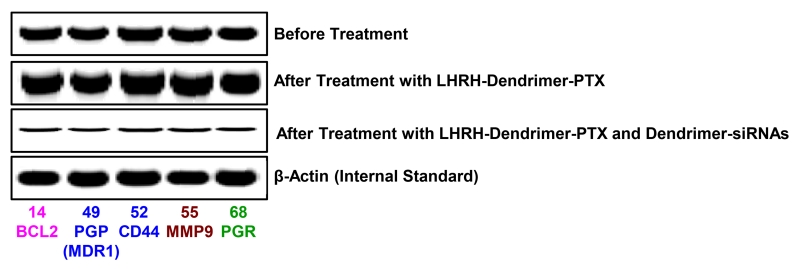

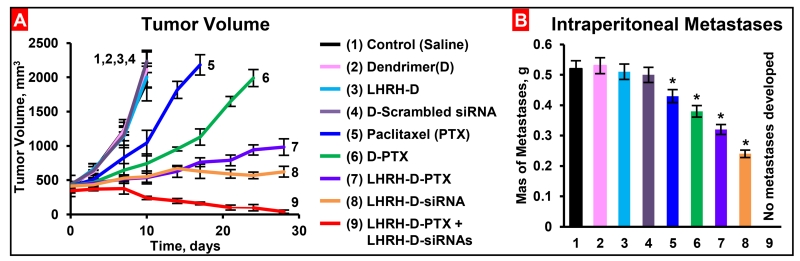

In order to support the proposed personalized approach, the expressions of mRNAs were measured in samples of primary tumors and malignant ascites obtained from different patients with ovarian carcinoma. Initially, the expression of 191 genes in cells isolated from these samples was analyzed using three different commercial cancer gene profiling qRT-PCR kits (Human Apoptosis and Breast Cancer RT2 ProfilerTM PCR Arrays and qBiomarker Copy Number PCR Array Human Ovarian Cancer, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Based on the results of these measurements, 83 genes were selected for the creation of a custom qRT-PCR array (Figure 11). The expression of luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) - an excellent ovarian cancer-targeting moiety [154, 155, 165] was also measured. We used previously selected and characterized multidrug resistant cells isolated from tumor samples of a patient with metastatic ovarian cancer and used these cells to initiate subcutaneous tumor in nude mice. The cells were labelled with luciferase as previously described [154] and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice. 15-20 days after transplantation primary tumors reached a size of ~0.4 cm3 and about 80% of mice developed intraperitoneal metastases. The progression of the subcutaneous tumor as well as intraperitoneal metastases was assessed by three different imaging systems (optical, MRI, ultrasound), direct measurements of the size/volume of primary tumors and intraperitoneal metastases and histopathological evaluation. Gene expression profile in the primary subcutaneous tumors was similar to those registered in the original resistant cells isolated form the patient. Five genes (BCL2, MDR1, CD44, MMP9, PGR) overexpressed in these cells were selected as targets specific for this patient (Figure 11). The overexpression of selected mRNAs was confirmed by the measurements of corresponding protein (Figure 12). In order to effectively deliver an anticancer drug (paclitaxel, PTX) and siRNA targeted to the selected genes/mRNAs, we developed a tumor-targeted (by the LHRH peptide) dendrimer-based delivery system [155, 166]. Treating the mice with free non-bound PTX or dendrimer-bound PTX without siRNA increased the expression of all five selected targets (Figure 11B). The application of dendrimer-bound PTX delivered in the mixture with dendrimers containing five siRNAs (selected specifically for this patient), decreased the expression of all target genes and proteins (Figure 11C and Figure 12). It should also be stressed that LHRH-targeted dendrimers accumulated predominately in the tumor, while similar but non-targeted dendrimers distributed mainly between the tumor, liver, spleen, kidney and lungs. Further experiments showed that non-bound free and non-targeted dendrimeric PTX triggered apoptosis in the tumor and several healthy organs inducing adverse side effects, only slightly delayed tumor growth and the development of intraperitoneal metastases. The delivery of PTX by dendrimers significantly enhanced the induction of cell death in the tumor and limited the side effects, while the combination of dendrimers containing PTX and five siRNAs targeted to the selected for this patient mRNAs (Figure 11) significantly enhanced cell death induction, imposed tumor shrinkage and completely prevented the development of intraperitoneal metastases (Figure 13). Consequently, these data support the proposed concept of nanotechnology approach for personalized treatment of ovarian cancer.

Figure 11.

Expression of genes (A, B, C, qPCR) in tumors of mice bearing xenografts of drug resistant malignant ascites obtained from a patient with ovarian carcinoma. The selected targeted genes for this patient are denoted in the table by red squares. Nude mice were inoculated with cancer cells. After tumors reached a size of about 0.4 cm3, mice were treated 8 times twice per week within 4 weeks with LHRH-Dendrimer-PTX (B) and LHRH-Dendrimer-PTX + LHRH- Dendrimer –siRNAs (C). Means ± SD are shown, n=4.

Figure 12.

Expression of targeted proteins (Western blotting) in tumors of mice bearing xenografts of drug resistant malignant ascites obtained from a patient with ovarian carcinoma. Nude mice were inoculated with cancer cells. After tumors reached a size of about 0.4 cm3, mice were treated 8 times twice per week within 4 weeks with LHRH-Dendrimer-PTX and LHRH-Dendrimer-PTX + LHRH-Dendrimer-siRNAs. Representative images of Western blots are shown.

Figure 13.

Tumor volume (A) and mass of intraperitoneal ascites (metastases, B) in mice bearing xenografts of drug resistant malignant ascites obtained from patients with ovarian carcinoma. After tumor reached a size of about 0.4 cm3, mice were treated 8 times twice per week within 4 weeks with substances indicated. Means ± SD are shown, n=4.

3.4. Integrating Data to Generate Personalized Ovarian Cancer Medicine Guidelines and Protocols

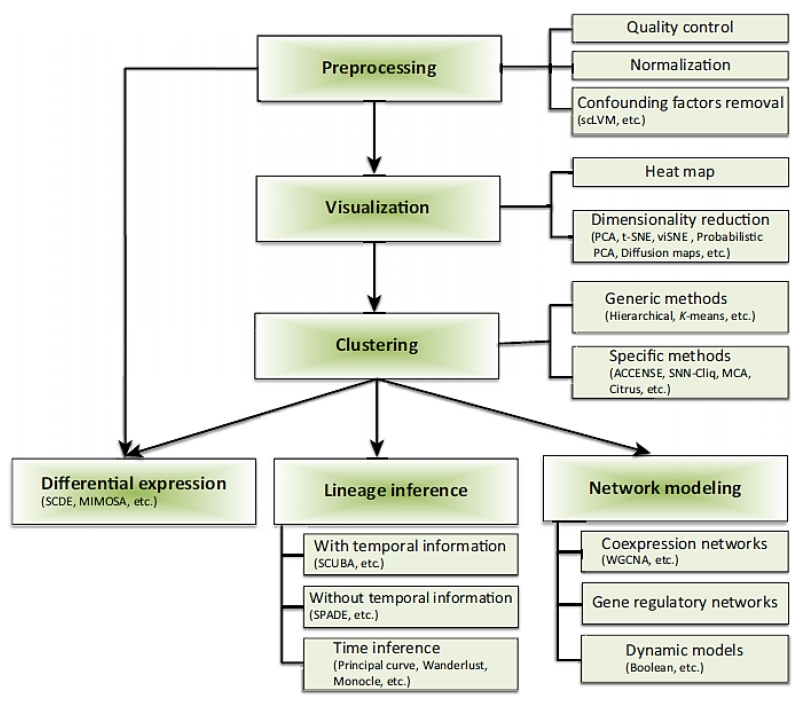

Integration of enormous libraries of data will make it easier to diagnose patients and allow for improved patient treatment outcomes (Figure 14). One such database is the cancer genome atlas (TCGA). The project began in 2005 and has been ever expanding since [167]. The project aims to incorporate molecular data discovered over the years. Ultimately, the goal is to set up these models, algorithms, and guideline protocols using cancer research data. The data from the TCGA could help provide biomarkers for diagnosing patient tumors with increased accuracy [168]. Then as research continues to advance, the tools can be adjusted and finely tuned to the point where mortality rates are reduced as much as humanly possible.

Figure 14.

A Typical Flowchart for Single-Cell Data Analysis. Reproduced with permission from [60].

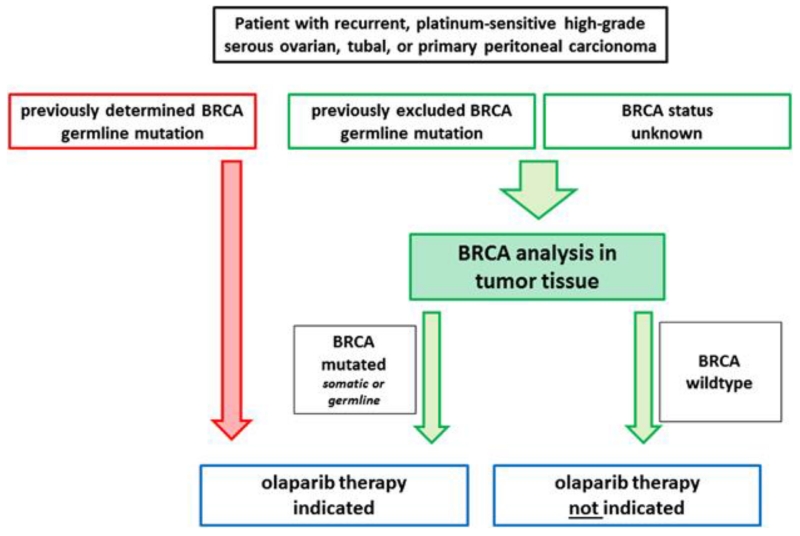

Modeling helps further stratify ovarian cancers beyond histological subtyping. Molecular biomarkers and clinical data can shape protocols for guiding oncologists to decide on an optimal treatment course for a particular patient. For instance, patients with germline mutations for BRCA 1/2 will benefit the most from a PARP inhibitor added to chemotherapy (Figure 15) [23]. Furthermore, if a patient is ER positive, then the addition of an ER agonist or estrogen antimetabolite could increase treatment efficacy.

Figure 15.

Algorithm for predictive BRCA testing in tumor tissue. Patients with recurrent, high-grade serous ovarian, tubal, or primary peritoneal carcinoma may be considered for an olaparib maintenance therapy. For patients with unknown BRCA status or patients who have previously been tested negative for a BRCA germline mutation BRCA status should be determined in tumor tissue, which enables the detection of germline and somatic mutations (green). Patients in whom a tumoral BRCA mutation is detected are eligible for therapy. Patients who have previously been tested positive for a germline BRCA mutation are eligible for therapy and do not need further testing (red). Reproduced with permission from [23].

5. Future Directions to Further Improve Personalized Ovarian Cancer Medicine

An enormous catalog of data exists from both the basic sciences and clinical research. To help oncologists decide on an optimal treatment course to use for a particular patient, certain screening guidelines and diagnostic protocols should be generated. At present, screening for ovarian cancer is limited. At present, the only two methods for screening for ovarian cancer are transvaginal ultrasound and the CA-125 blood test. Controversy surrounds the efficacy of screening patients using these methods [66]. Therefore, new predictive biomarkers are essential for earlier detection of ovarian tumors in patients. Targeted therapeutics has come a long way for ovarian cancer care and demonstrate a clinical promise in the future. The key to efficacious personalized cancer care is to discover and diagnose tumors as early and accurately as possible. This is the main obstacle for ovarian cancer care and needs to be improved in order to improve the patient treatment outcomes and reduce patient mortality rates. If ovarian tumors can be detected early, especially when the patient is presymptomatic, patients will have the greatest chance for overcoming the disease and destroying ovarian malignancies.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- CDC

complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CEL-seq

single-cell RNA-sequencing

- DOC

doxorubicin

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FRα

Folate receptor alpha

- HER

human epidermal growth factor receptor

- LHRH

luteinizing hormone releasing hormone

- MAB

monoclonal antibody

- MDA

multiple displacement amplification

- MIBI

Multiplexed ion beam imaging

- mRNA-seq

mRNA sequencing

- NGS

next generation sequencing

- OS

overall survival

- P4

predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory

- PARE

personalized analysis of rearranged ends

- PARP

Poly-ADP ribose polymerase

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PLD

PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin

- QOL

quality of life

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SNS

single-nucleus sequencing

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- TDS

targeted delivery system

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WGA

whole-genome amplification

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].A.C. Society . Ovarian Cancer. Vol. 2015. American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Loeb KR, Loeb LA. Significance of Multiple Mutations in Cancer. Carcinogeneis. 2000;21:379–385. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kurman RJ, Shih I-M. The Origin and Pathogenesis of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Proposed Unifying Theory. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2010;34:433–443. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ricciardelli C, Oehler MK. Diverse molecular pathways in ovarian cancer and their clinical significance. Maturitas. 2009;62:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen F, Zhuang X, Lin L, Yu P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Hu G, Sun Y. New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2015;13:45. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tian Q, Price ND, Hood L. Systems cancer medicine: towards realization of predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory (P4) medicine. J Intern Med. 2012;271:111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Du W, Elemento O. Cancer systems biology: embracing complexity to develop better anticancer therapeutic strategies. Oncogene. 2015;34:3215–3225. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang E. Cancer Systems Biology. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu ET, Lauffenburger DA. Systems Biomedicine: Concepts and Perspectives. Elsevier Science; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Barillot E, Calzone L, Hupe P, Vert JP, Zinovyev A. Computational Systems Biology of Cancer. Taylor & Francis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chow LM, Endersby R, Zhu X, Rankin S, Qu C, Zhang J, Broniscer A, Ellison DW, Baker SJ. Cooperativity within and among Pten, p53, and Rb pathways induces high-grade astrocytoma in adult brain. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zbuk KM, Eng C. Cancer phenomics: RET and PTEN as illustrative models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:35–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Konstantinopoulos PA, Matulonis UA. Current status and evolution of preclinical drug development models of epithelial ovarian cancer. Front Oncol. 2013;3:296. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].A.C. Society . Cancer Facts and Figures, 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, Dobrovic A, Birrer MJ, Webb PM, Stewart C, Friedlander M, Fox S, Bowtell D, Mitchell G. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2654–2663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Foulkes WD. Inherited Susceptibility to Common Cancers. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:1243–1253. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Grada A, Weinbrecht K. Next-generation sequencing: methodology and application. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:e11. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moshehi R, Chu W, Karlan B, Fishman D, Risch H, Fields A, Smotkin D, Ben-David Y, Reosenblatt J, Russo D, Schwartz P, Tung N, Warner E, Rosen B, Friedman J, Brunet J-S, Narod SA. BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Analysis of 208 Ashkenazi Jewish Women with Ovarian Cancer. The American Society of Human Genetics. 2000;66:1272–2000. doi: 10.1086/302853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Whitemore AS, Gong G, Itnyre J. Prevalence and Contribution of BRCA1 Mutations in Breast Cancer and Ovarian Cancer - Results from Three US Population-Based Case-Control Studies of Ovarian Cancer. The American Society of Human Genetics. 1997;60:496–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DEC, Rosen B, Bradley L, Kwan E, Jack E, Vesprini DJ, Kuperstein G, Abrahamson JLA, Fan I, Wong B. Prevalence and Penetrance of Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in a Population of 649 women with Ovarian Cancer. The American Society of Human Genetics. 2001;68:700–710. doi: 10.1086/318787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dietel M, Johrens K, Laffert MV, Hummel M, Blaker H, Pfitzner BM, Lehmann A, Denkert C, Darb-Esfahani S, Lenze D, Heppner FL, Koch A, Sers C, Klauschen F, Anagnostopoulos I. A 2015 update on predictive molecular pathology and its role in targeted cancer therapy: a review focussing on clinical relevance. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:417–430. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2015.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Leary RJ, Kinde I, Diehl F, Schmidt K, Clouser C, Duncan C, Antipova A, Lee C, McKernan K, De La Vega FM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA, Jr., Velculescu VE. Development of personalized tumor biomarkers using massively parallel sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:20ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rhodes DR, Chinnaiyan AM. Integrative analysis of the cancer transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2005;37(Suppl):S31–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stahlberg A, Zoric N, Aman P, Kubista M. Quantitative Real-Time PCR for Cancer Detection - the Lymphoma Case. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2005;5:221–230. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Aerts J, Wynendaele W, Paridaens R, Christiaens MR, van den Bogaert W, van Oosterom AT, Vandekerckhove F. A Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) to Detect Breast Carcinoma Cells in Peripheral Blood. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:39–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1008317512253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Warrenfeltz S, Pavlik S, Datta S, Kraemer ET, Benigno B, McDonald JF. Gene expression profiling of epithelial ovarian tumours correlated with malignant potential. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yan W, Herman JG, Guo M. Epigenome-Based Personalized Medicine in Human Cancer, Epigenomics. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van’t Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AAM, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, van der Velde T, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, Bernards R. A Gene-Expression Signature as a Predictor of Survival in Breast Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr., Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Luco RF, Pan Q, Tominaga K, Blencowe BJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science. 2010;327:996–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1184208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. Charting Histone Modifications and the Functional Organization of Mammalian Genomes. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Verma M. In: Advances in Cancer Biomarkers. Scatena R, editor. Springer; Netherlands: 2015. pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Keita M, Wang ZQ, Pelletier JF, Bachvarova M, Plante M, Gregoire J, Renaud MC, Mes-Masson AM, Paquet ER, Bachvarov D. Global methylation profiling in serous ovarian cancer is indicative for distinct aberrant DNA methylation signatures associated with tumor aggressiveness and disease progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang H, Liu T, Zhang Z, Payne SH, Zhang B, McDermott JE, Zhou JY, Petyuk VA, Chen L, Ray D, Sun S, Yang F, Chen L, Wang J, Shah P, Cha SW, Aiyetan P, Woo S, Tian Y, Gritsenko MA, Clauss TR, Choi C, Monroe ME, Thomas S, Nie S, Wu C, Moore RJ, Yu KH, Tabb DL, Fenyo D, Bafna V, Wang Y, Rodriguez H, Boja ES, Hiltke T, Rivers RC, Sokoll L, Zhu H, Shih Ie M, Cope L, Pandey A, Zhang B, Snyder MP, Levine DA, Smith RD, Chan DW, Rodland KD, C. Investigators Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization of Human High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ohman AW, Hasan N, Dinulescu DM. Advances in tumor screening, imaging, and avatar technologies for high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:322. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ghosh D, Bagley AF, Na YJ, Birrer MJ, Bhatia SN, Belcher AM. Deep, noninvasive imaging and surgical guidance of submillimeter tumors using targeted M13-stabilized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13948–13953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400821111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Savla R, Minko T. Nanoparticle design considerations for molecular imaging of apoptosis: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic value. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016 Jun 29; doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.016. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Savla R, Garbuzenko OB, Chen S, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Minko T. Tumor-targeted responsive nanoparticle-based systems for magnetic resonance imaging and therapy. Pharm Res. 2014;31:3487–3502. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1436-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Picotti P, Bodenmiller B, Mueller LN, Domon B, Aebersold R. Full Dynamic Range Proteome Analysis of S. cerevisiae by Targeted Proteomics. Cell. 2009;138:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bianco R, Gelardi T, Damiano V, Ciardiello F, Tortora G. Rational Bases for the Development of EGFR Inhibitors for Cancer Treatment. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39:1416–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Khan DR, Webb MN, Cadotte TH, Gavette MN. Use of Targeted Liposome-based Chemotherapeutics to Treat Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2015;9:1–5. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S29421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsay V, Wicha M, Clarke MF, Simeone DM. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a Cancer Stem Cell in Human Brain Tumors. Cancer Research. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bedard PL, Hansen AR, Ratain MJ, Siu LL. Tumour Heterogeneity in the Clinic. Nature. 2013:501. doi: 10.1038/nature12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hofree M, Shen JP, Carter H, Gross A, Ideker T. Network-based stratification of tumor mutations. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nicholas CR, Gaur M, Wang S, Pera RA, Leavitt AD. A Method for Single-Cell Sorting and Expansion of Genetically Modified Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2007;16:109–117. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Thorsen T, Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. Microfluidic Large-Scale Integration. Science. 2002;298:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1076996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, Andrews P, Rodgers L, McIndoo J, Cook K, Stepansky A, Levy D, Esposito D, Muthuswamy L, Krasnitz A, McCombie WR, Hicks J, Wigler M. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dean FB, Hosono S, Fang L, Wu X, Faruqi AF, Bray-Ward P, Sun Z, Zong Q, Du Y, Du J, Driscoll M, Song W, Kingsmore SF, Egholm M, Lasken RS. Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082089499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hou Y, Song L, Zhu P, Zhang B, Tao Y, Xu X, Li F, Wu K, Liang J, Shao D, Wu H, Ye X, Ye C, Wu R, Jian M, Chen Y, Xie W, Zhang R, Chen L, Liu X, Yao X, Zheng H, Yu C, Li Q, Gong Z, Mao M, Yang X, Yang L, Li J, Wang W, Lu Z, Gu N, Laurie G, Bolund L, Kristiansen K, Wang J, Yang H, Li Y, Zhang X, Wang J. Single-cell exome sequencing and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell. 2012;148:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xu X, Hou Y, Yin X, Bao L, Tang A, Song L, Li F, Tsang S, Wu K, Wu H, He W, Zeng L, Xing M, Wu R, Jiang H, Liu X, Cao D, Guo G, Hu X, Gui Y, Li Z, Xie W, Sun X, Shi M, Cai Z, Wang B, Zhong M, Li J, Lu Z, Gu N, Zhang X, Goodman L, Bolund L, Wang J, Yang H, Kristiansen K, Dean M, Li Y, Wang J. Single-cell exome sequencing reveals single-nucleotide mutation characteristics of a kidney tumor. Cell. 2012;148:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tang F, Barbacioru C, Wang Y, Nordman E, Lee C, Xu N, Wang X, Bodeau J, Tuch BB, Siddiqui A, Lao K, Surani MA. mRNA-Seq Whole Transcriptome Analysis of a Single Cell. Nature Methods. 2009;6:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dalerba P, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, Rajendran PS, Rothenberg ME, Leyrat AA, Sim S, Okamoto J, Johnston DM, Qian D, Zabala M, Bueno J, Neff NF, Wang J, Shelton AA, Visser B, Hisamori S, Shimono Y, Van De Wetering M, Clevers H, Clarke MF, Quake SR. Single-Cell Dissection of Transcriptional Heterogeneity in Human Colon Tumors. Nature Biotechnology. 2012;29:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ramskold D, Luo S, Wang YC, Li R, Deng Q, Faridani OR, Daniels GA, Khrebtukova I, Loring JF, Laurent LC, Schroth GP, Sandberg R. Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:777–782. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shalek AK, Satija R, Adiconis X, Gertner RS, Gaublomme JT, Raychowdhury R, Schwartz S, Yosef N, Malboeuf C, Lu D, Trombetta JJ, Gennert D, Gnirke A, Goren A, Hacohen N, Levin JZ, Park H, Regev A. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature. 2013;498:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Saadatpour A, Lai S, Guo G, Yuan GC. Single-Cell Analysis in Cancer Genomics. Trends Genet. 2015;31:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hashimshony T, Wagner F, Sher N, Yanai I. CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell Rep. 2012;2:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, Trombetta JJ, Weitz DA, Sanes JR, Shalek AK, Regev A, McCarroll SA. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Klein AM, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, Tallapragada N, Veres A, Li V, Peshkin L, Weitz DA, Kirschner MW. Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2015;161:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el AD, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, Balderas RS, Plevritis SK, Sachs K, Pe’er D, Tanner SD, Nolan GP. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Angelo M, Bendall SC, Finck R, Hale MB, Hitzman C, Borowsky AD, Levenson RM, Lowe JB, Liu SD, Zhao S, Natkunam Y, Nolan GP. Multiplexed ion beam imaging of human breast tumors. Nat Med. 2014;20:436–442. doi: 10.1038/nm.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, Johnson CC, Lamerato L, Isaacs C, Reding DJ, Greenlee RT, Yokochi LA, Kessel B, Crawford ED, Church TR, Andriole GL, Weissfeld JL, Fouad MN, Chia D, O’Brien B, Ragard LR, Clapp JD, Rathmell JM, Riley TL, Hartge P, Pinsky PF, Zhu CS, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS, Miller AB, Xu JL, Prorok PC, Gohagan JK, Berg CD, Team PP. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2295–2303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]