Summary

The diencephalon is the primary relay network transmitting sensory information to the anterior forebrain. During development, distinct progenitor domains in the diencephalon give rise to the pretectum (p1), the thalamus and epithalamus (p2) and the prethalamus (p3), respectively. Shh plays a significant role in establishing the progenitor domains. However, the upstream events influencing the expression of Shh are largely unknown. Here, we show that Barhl2 homeobox gene is expressed in the p1 and p2 progenitor domains and the in zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI), and regulates the acquisition of identity of progenitor cells in the developing diencephalon. Targeted deletion of Barhl2 results in the ablation of Shh expression in the dorsal portion of ZLI and causes thalamic p2 progenitors to take the fate of p1 progenitors and form pretectal neurons. Moreover, loss of Barhl2 leads to the absence of thalamocortical axon projections, the loss of habenular afferents and efferents, and a gross diminution of the pineal gland. Thus, by acting upstream of Shh signaling pathway, Barhl2 plays a crucial role in patterning the progenitor domains and establishing the positional identities of progenitor cells in the diencephalon.

Introduction

The thalamus is a major relay center in the brain that regulates the transfer of sensory and motor information from peripheral sensory systems to the cortex. The thalamus and epithalamus together serve many functions including but not limited to learning, motor control, regulating sleep-awake cycle, and regulating dopaminergic systems for mood disorders [1]. The thalamus and epithalamus develop from the diencephalon that can be divided into three progenitor domains or ‘prosomeres’ along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis [2–4]. Prosomere (p) 1, p2 and p3 give rise to pretectum, thalamus and epithalamus and prethalamus, respectively.

Wedged in between the p2 and p3 domains is the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI), which acts as an ‘organizer’ to regulate diencephalic regionalization and patterning [5]. The ZLI is identified by the expression of the morphogen sonic hedgehog (Shh). There is significant evidence implicating the early expression of Shh both in the ZLI and the diencephalic basal plate as an important cue in establishing thalamic anlage [6–10]. Graded Shh expression is also required for specific regionalization within the thalamus with a higher concentration of the morphogen being required for the development of the rostral thalamus (rTh) compared to a much lower concentration for that of the caudal thalamus (cTh) [7]. Shh also influences the development of p3 progenitor domain and hence the prethalamus by causing the expression of genes different from those expressed by the thalamus [6, 11]. While we understand the importance of Shh expression in the ZLI in establishing diencephalic progenitor domains, the upstream molecular mechanisms regulating Shh signaling and hence patterning of the diencephalon is not completely understood.

Previous studies have shown that the BarH-like homeodomain 2 (BARHL2) transcription factor plays critical roles in the specification of retinal cell types [12] and in regulating the divergence of proprioceptive spinal cord dorsal interneurons into its subtypes [13]. The expression of Barhl2 has also been identified in the developing diencephalon [14, 15]. To address the role of Barhl2 in patterning the diencephalon, we used Barhl2lacZ and Barhl2Cre knock-in mouse lines that were described in our previous studies [12, 13]. We show here that Barhl2-null animals have thalamic and epithalamic insufficiencies reflected by the absence of thalamocortical axon projections. We also show that progenitor cells from the p2 thalamic domain acquire some of the attributes of p1 pretectal neurons in the absence of Barhl2. Furthermore, we provide evidence of Barhl2 being upstream of Shh signaling and playing a direct role in patterning the p1 and p2 progenitor domains.

Results

Barhl2-null animals lack thalamocortical axon projections

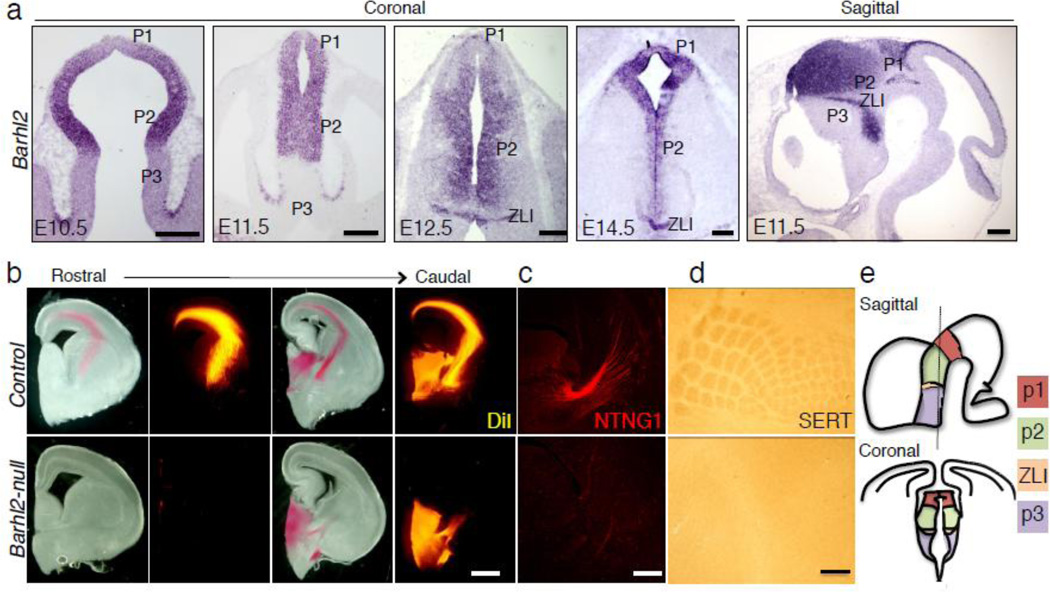

Barhl2 is expressed in p1 and p2 progenitor domains and the ZLI at early stages of the developing diencephalon (Fig. 1a) Expression of Barhl2 was seen as early as E10.5 in the developing diencephalon. As development proceeds, its expression is seen in p1 and p2 progenitor domains and the ZLI. To probe the importance of Barhl2 in the diencephalic progenitor domains, we first examined the thalamus in the Barhl2-null animals at E17.5-E18.5, embryonic time points at which thalamic nuclei are well defined, and found that the Barhl2-null animals lacked thalamocortical axon projections as revealed by DiI anterograde tracing (Fig. 1b) and Netrin-G1 staining (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, while the segregation of thalamocortical afferents into vibrissal patterned barrels was readily visualized in the somatosensory cortex of the control animals, they were missing in the Barhl2-null mice, confirming the lack of cortical projections from the thalamus (Fig. 1d). The anterior thalamic nuclei were not specified at E17.5 as seen by the loss of expression of PROX1 (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Loss of thalamocortical axons in Barhl2-null mice. (a) In situ hybridization of caudal sections at various time points and of representative sagittal section at E11.5 shows Barhl2 expression in the developing diencephalon. (b) DiI tracing of thalamocotrical axons at E18.5 shows a loss of cortical projections in Barhl2-null mice. (c) Anti-NTNG1 immunohistochemistry displays the loss of thalomo-cortical afferents in Barhl2-nulls at E17.5. (d) Anti-SERT immunohistochemistry of tangential cortical sections reveals the loss of distinct vibrissal patterned barrels in Barhl2-null mice at P8. (e) Schematic representation of sagittal and coronal sections of the diencephalon outlines the positions of different progenitor domains and ZLI. Scale bars in a, c and d equals 200 µm and in b equals 500 µm.

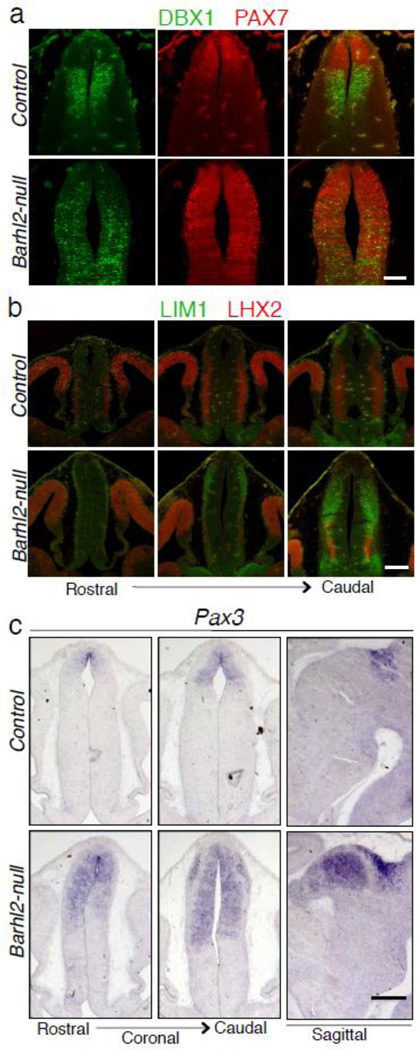

p1 progenitor domain markers are ectopically expressed in the presumptive p2 progenitor domain

We then investigated the fate of p2 progenitor cells that give rise to the thalamus and epithalamus. DBX1 is expressed in the thalamic progenitor cells in the ventricular zone and is expressed in a graded fashion with strong expression in the dorsal side of the caudal thalamus and a significantly weaker expression in the ventral side of the caudal thalamus [16]. In Barhl2-null brains at E12.5, the expression of DBX1 was not restricted to the ventricular zone, but was also present in the mantle zone. In addition, the graded expression pattern of DBX1 was lost (Fig. 2a). We found the same to be true at earlier time points at E10.5 and E11.5 (Fig. S2). PAX7 expression, which marks the post-mitotic cells of the p1 domain [16] in the control at E12.5, was expressed throughout the presumptive p2 domain in the Barhl2-null (Fig. 2a). Consistently, LIM1 and Pax3, also markers for post-mitotic p1 neurons [17], were ectopically expressed in the presumptive p2 domain in the Barhl2-null (Fig. 2b, c). While LHX2 and LHX9 is normally expressed in post-mitotic caudal thalamic neurons [18], its expression in the caudal thalamus was severely attenuated in the null (Fig. 2b, S2). Taken together, these results suggest that the p2 progenitor cells acquire some of the attributes of p1 pretectal neurons in the Barhl2-null diencephalon.

Figure 2.

Mis-expression of pretectal neuron markers in the absence of Barhl2. (a) Immunolabeling reveals that the confined expression of DBX1 (green) in thalamic progenitor cells is disrupted and that PAX7 (red) expression expands from the p1 domain to the presumptive p2 domain in the Barhl2-null mice at E12.5. (b and c) A similar fate switch is seen by expression of LIM1 (green in b) and Pax3 (c), markers for prectectal neurons and LHX2 (red in b) expression is down-regulated in the dorsal thalamic neurons of the Barhl2-null mice at E12.5. Scale bars equal 200 µm.

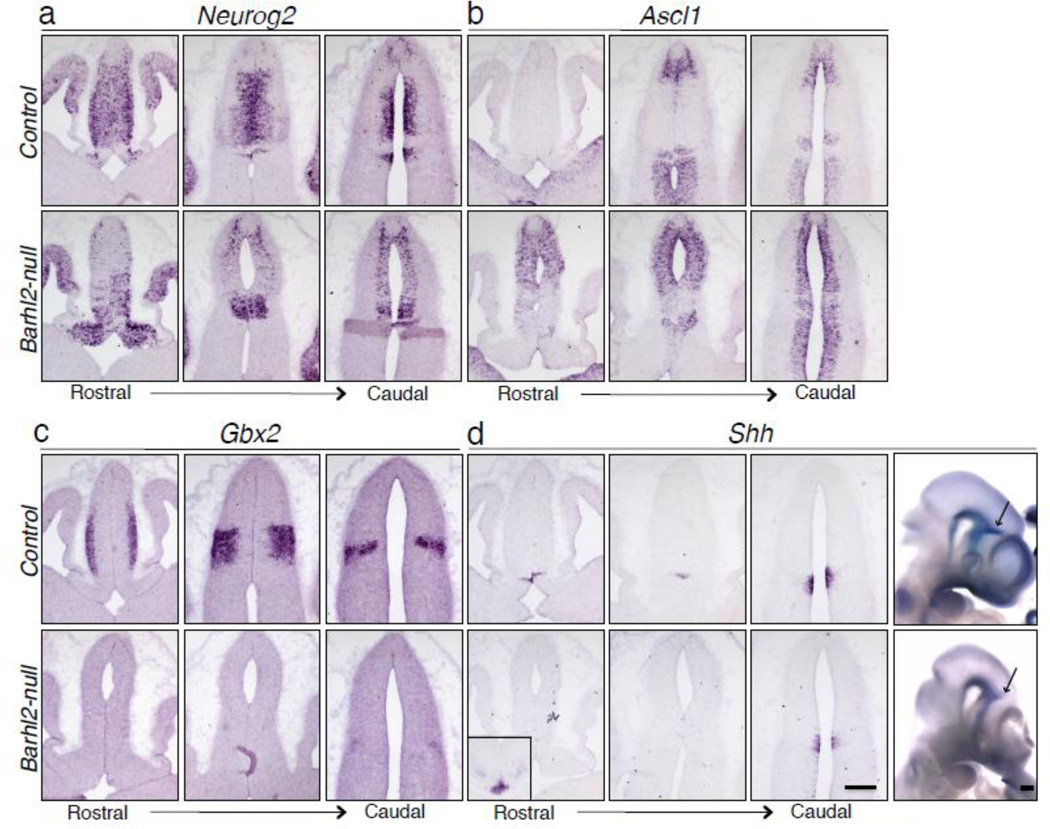

Barhl2 acts upstream of Shh to control the patterning of p1 and p2 progenitor domains and the development of ZLI

During the establishment of the p1 and p2 domains, Neurog2 is expressed in the ventricular surface of p2 progenitor cells and in the ZLI. The expression of Neurog2 inhibits that of Ascl1 [19]. Hence Ascl1 is complementarily expressed in the p1 domain, the rostral thalamus region of the p2 domain and the p3 domain [14, 16]. Upon Barhl2 deletion, the compartmentalized expression patterns of Neurog2 and Ascl1 were disrupted (Fig. 3a, b). The attenuation of Neurog2 expression with a concomitant up-regulation of Ascl1 in the presumptive p2 domain provides further evidence that the p2 progenitor cells likely acquire pretectal traits. However, there still remained a small region of the diencephalon that expressed both DBX1 and ASCL1 (Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Barhl2 acts upstream of Shh and regulates pro-neural gene expression. In the Barhl2-null mice at E12.5, the compartmentalized expression of Neurog2 in the ZLI and the caudal thalamic p2 neurons is disrupted (a). The distinctive expression of Ascl1 in the pretectal p1 neurons, rostral thalamic p2 neurons and prethalamic p3 neuorns is disrupted (b). Gbx2 expression in p2 thalamic neurons is nearly abolished (c). Shh expression in the ZLI is restricted to the ventral portion of ZLI while its dorsal expression is lost (d) both in coronal sections and whole-mount images, inset showing the normal expression of Shh in the notochord. Scale bars equal 200 µm.

We further examined the expression of Gbx2, which is expressed in the thalamic progenitors [20, 21], and found its expression abolished in the Barhl2-null (Fig. 3c). Previous studies have shown that Shh plays an essential role in regulating Gbx2 expression and that blocking Shh signaling in the dorsal portion of ZLI leads to a reduction in Gbx2 expression [6]. We thus compared the expression of Shh in the control and Barhl2-null, and found that Shh expression was ablated in the dorsal region and was restricted to the ventral portion of the ZLI (Fig. 3d), suggesting that the progression of ZLI formation is attenuated prematurely owing to the ventral restriction of Shh. Taken together, these results indicate that Barhl2 acts upstream of Shh to regulate the progression of ZLI and the patterning of p1 and p2 domains.

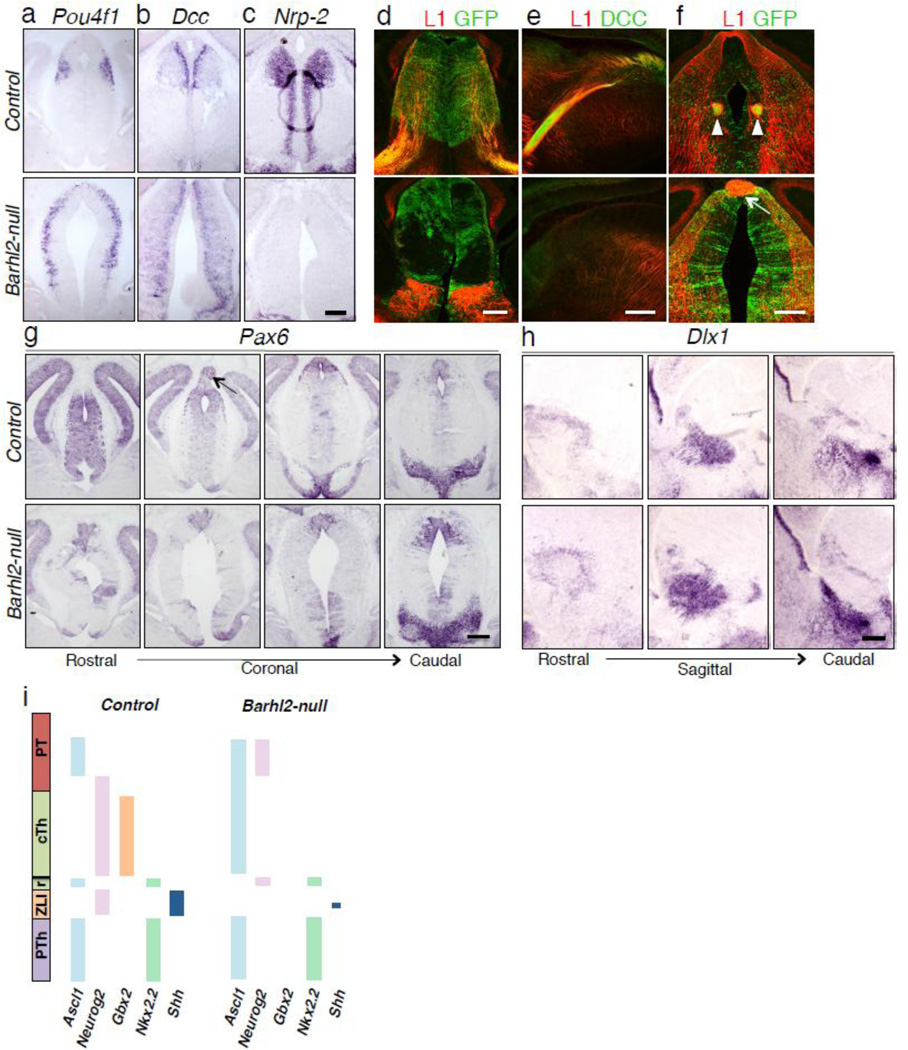

Loss of Barhl2 affects the development of epithalamus structures

To determine whether loss of Barhl2 affected other future components of the p2 domain namely the habenula and pineal gland (collectively called the epithalamus), we examined the expression of markers of epithalamus structures in Barhl2-null mice. Pou4f1 is a habenular marker expressed in the alar plate of the caudal p2 domain at the border between p1 and p2 [22]. In the Barhl2-null mutant, Pou4f1 is ectopically expressed in the p1 progenitor domain and further into the presumptive p2 domain (Fig. 4a). A similar expansion in the expression of the deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc), the receptor for netrin ligand expressed in the floor plate [23], was seen in the habenular neurons (Fig. 4b). The expression of neuropilin-2 (Nrp2), which is required along with semaphorin 3F (Sema3F) for habenular axon guidance [23, 24], was also abolished in the Barhl2-null (Fig. 4c). A functional habenula is thus not established in the Barhl2-null since the afferent input to the habenula via the stria terminalis (Fig. 4d) and the efferent connections from the habenula via the fasciculus retroflexus (Fig. 4e, f) were severely attenuated. The posterior commissure connecting the pretectal nuclei was also enlarged in the Barhl2-null mutant compared to the control (Fig. 4f). Additionally, Pax6 expression in the developing diencephalon [25] revealed the absence of a pineal gland in the Barhl2-null (Fig. 4g). While the p1 and p2 progenitor domains were affected, an analysis of expression of Dlx1 showed that the p3 progenitor domain remained unaffected in the Barhl2-null animals (Fig. 4h). Taken together, loss of Barhl2 leads to a loss of the developmental components of the p2 domain. A diagrammatic summary of molecular factors affected due to the loss of Barhl2 is illustrated in Fig. 4i.

Figure 4.

Absence of Barhl2 leads to a loss of other p2 progenitor domain structures. (a-c) At E14.5, Pou4f1, a habenular neuron marker is ectopically expressed in p1 and p2 domain neurons in the Barhl2-null mice (a). Dcc expression in habebular axons is similarly affected in the Barhl2-null mice (b). The expression of Nrp2, a habenular axon guidance molecule is abolished in the Barhl2-null mice (c). (d-f) At E14.5, the expression of L1 in stria terminalis, the habenular afferent is abolished in the Barhl2-null mice (d). Efferent output from the habenula provided by the fasciculus retroflexus as seen by the expression of L1 is abolished in the Barhl2-null mice (e). Expression of L1 displays a hyperfasciculation of the posterior commissure (arrow) in the null mutant as compared to the control (f). Arrowheads indicate the presence of fasciculus retroflexus in the control as compared to the mutant (f). Expression of Pax6 at E12.5 across all progenitor domains is affected in the null mutant and displays a loss of pineal gland (arrow) (g). Expression of Dlx1, a marker for the p3 progenitor domain is unaltered in the Barhl2-null mutant (h). A summary of affected factors encompassing various progenitor domains in the Barhl2 mutant as compared to the control is schematically represented (i) (Figure schematic adapted and modified from [33]). Scale bars equal 200 µm.

Discussion

The thalamus relays sensory information from peripheral nervous system to the cortex to bring about conscious perception and is indispensible for the vitality of an animal. The habenula acts as a relay in connecting the forebrain with the midbrain and hindbrain and is implicated in several disorders such as depression and schizophrenia. The pineal gland mainly regulates the sleep-wake cycle. Furthermore, thalamocortical afferents affect the expression of developmental genes in the neocortex and are crucial for the establishment of neocortical identities [26]. In this study we show that Barhl2 is essential for the development of these diencephalic structures and that in Barhl2-null mice, cells in the p2 progenitor domain acquire attributes of p1 progenitor domain while p3 progenitor domain remains unaffected.

In the absence of Barhl2, expression of p1 progenitor domain neuron markers such as Pax7, Pax3 and Lim1 expands into the presumptive p2 progenitor domain. Previous studies have shown that a loss of Gbx2 disrupts the border between the epithalamus and pretectum [21], which is consistent with our results and may explain the cell fate mixing between cells in p1 and p2 prosomeres. Moreover, Barhl2-nulls also display a severe attenuation of Lhx2 expression, a marker for p2 progenitor domain neurons (Fig. 2). This mis-specification can be attributed to the mis-expression of neural bHLH genes Neurog2 and Ascl1 in the Barhl2-nulls (Fig. 3 a, b). While the expression of Neurog2 and Pax6 in the Barhl2-nulls is largely missing from the presumptive p2 domain, the appearance of patchy expression of the markers in parts of the p2 prosomere domain cannot be ignored. Previous studies have demonstrated that the ZLI functions as an ‘organizer’ that prevents the mixing of neighboring cell types. It is hence plausible that the dorsal truncation of the ZLI leads to some cell mixing between the p2 and p3 prosomeres, leading to the presence of Neurog2 and Pax6 positive p3 cells in the presumptive p2 domain. Hyperfasciculation of the posterior commissure further lends credence to a fate switch of the p2 progenitors into the p1 pretectal neurons (Fig. 4f). Since the pretectal nuclei are interconnected by the posterior commissure and there is an expansion of the overall p1 domain at the expense of p2 progenitors, it is plausible that the additional pretectal neurons contribute to the hyperfasciculated posterior commissure. However, the p3 progenitor domain remains unaffected in Barhl2-nulls, as seen by the expression of Dlx1, a marker for p3 domain progenitor neurons. This is a surprising result since a disruption in Shh signaling affects the development of both p2 and p3 progenitor domains [6, 11]. One plausible explanation for this might be that the ventral expression of Shh in the ZLI contributes in part to the normal development of p3 progenitor domain in Barhl2-null animals.

We have showed that in the absence of Barhl2, the p2 progenitor domain structures: the thalamus and the epithalamus are severely attenuated. Furthermore, loss of expression of markers for thalamic progenitor cells Gbx2 (Fig. 1c) and Pax6 [27] (Fig. 1g) in the presumptive p2 domain in Barhl2-null animals supports the claim that Barhl2-null animals lack a thalamus. While Barhl2 seems to affect Pax6 expression in the p2 domain of the developing diencephalon, whether this ties into the regulation of Shh in the ZLI is currently unknown. Furthermore the absence of thalamocortical afferents (Fig. 1b, 1c) and vibrissal staining in the somatosensory cortex proves the absence of a functional thalamus in the Barhl2-nulls (Fig. 1d). Similarly we display the loss of a habenular and pineal gland epithalamic structures using markers such as Pou4f1, Dcc, Nrp-2 and Pax6 (Fig. 4). Taken together, Barhl2 is a key regulator of Shh and controls the early patterning of the diencephalon. In the absence of Barhl2, p2 prosomere domain progenitors acquire attributes of p1 progenitor domain neurons. It is thus crucial for the development of p2 domain structures: the thalamus and epithalamus.

We show that the loss of Barhl2 leads to the down-regulation of Shh, suggesting that Barhl2 could regulate the early patterning of diencephalon by acting upstream of Shh. Interestingly, the expression of Shh is not abolished in the absence of Barhl2 (Fig. 3d, S3). Rather, it is restricted to the ventral portion of the ZLI. Shh is expressed initially in the basal plate of p1-p3 and later in the ZLI as patterning of the diencephalon proceeds [10, 28]. Once initiated in the developing ZLI, it expands dorsally thus forming a barrier between p2 and p3 domains [29]. One possibility is that Barhl2 could have a role in regulating the dorsal expansion of Shh expression but not the initiation of Shh expression in the ZLI. Since Barhl2 expression begins at E10.5 in the developing diencephalon and expression of Shh begins at E9 in the ZLI [29], it is likely that loss of Barhl2 restricts the dorsal expansion of ZLI. Recently published studies have identified a Shh ZLI enhancer of evolutionary origin and have demonstrated that BARHL2 directly binds to this enhancer in E10.5 mouse embryo brains [30]. Moreover, studies in Xenopus have shown that Barhl2 restricts the dorsal expansion of the ZLI by affecting the competence of neuroepithelial cells to respond to the secreted form of SHH from the alar plate [31]. Previous studies have also shown that Gbx2 expression is regulated by Shh and that blocking Shh signaling in the dorsal portion of ZLI attenuates Gbx2 expression [6]. Additionally, studies have shown that Shh promotes thalamic specification by activating Gbx2 [32] and that the dorsal extension of Shh expression in the ZLI is crucial for normal gene expression in the thalamus [6]. Here we have shown that the loss of Barhl2 abolishes Shh expression in the dorsal portion of ZLI and that loss of Barhl2 also leads to an attenuation of Gbx2 expression in p2 domain. Our results taken in conjunction with previously published data argue for the role of Barhl2 in regulating the patterning of the developing diencephalon by directly controlling the expression of Shh in the Barhl2 to Shh to Gbx2 regulatory pathway.

Experimental procedures

Animals

All animal procedures in this study were approved by the University Committee of Animal Resources at the University of Rochester. Barhl2lacz/+ and Barhl2Cre/+ mice were generated previously (10). Embryos were designated as E0.5 at noon on the day vaginal plug was first observed in the breeding mother. Pups were designated P0 on the day of birth.

Immunohistochemistry and In situ hybridization

Time-mated embryos were dissected in cold PBS and fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, following which they were equilibrated in 30% (w/v) sucrose at 4°C overnight and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and sectioned at 18–30 µm on a cryostat. Sections were collected on slides and were processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or in situ hybridization (ISH).

The following antibodies were used for IHC: Anti-DBX1 (1:1,000, gift from Y. Nakagawa), Anti-DCC (1:500, Santa Cruz), Anti-GFP (1:1000, Abcam), Anti-L1 (1:200, Chemicon), Anti-LHX2 (1:200, Santa Cruz), Anti-LHX9 (1:200, Santa Cruz), Anti-LIM1 (1:500, DSHB), Anti-ASCL1 (1:200, R&D Systems), Anti-NKX2.2 (1:200, DSHB), Anti-PAX7 (1:200, DSHB), Anti-PROX1 (1:500, Covance), Anti-SERT (1:500, Immunostar), Anti-SHH (1:500, R&D Systems). Alexa conjugated antibodies (1:1,000, Molecular probes) were used for visualization.

The following probes were used for ISH: Barhl2 (Gift from M. Xiang), Pax3 (Gift from L. Puelles), Neurog2 (657-1497 of NM009718.2), Ascl1 (Gift from A. Joyner), Shh (Gift from A. McMahon), Gbx2 (Gift from A. Joyner), Pou4f1 (267-1497 of NM011143.4), Dcc (Gift from Z.F. Chen), Nrp2 (984-1911 of AF022857), Pax6 (Gift from X. Zhang), Lhx2 (1149-1806 of AF124734), and Dlx1 (1501-2277 of NM010053).

DiI tracing

To visualize thalamocortical axon projections, DiI crystals (Molecular Probes) were applied to the thalamus of E17.5 brain and placed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 14 days. 50 µm sections were obtained on a vibratome and were visualized under the 543 nm filter in a ZEISS stereoscope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Libby, A. Kiernan, P. White, and the members of Gan laboratory for their insightful discussions and technical assistance. This research was supported by The National Institute of Health grant 1R21EY023104, Zhejiang Province Science Grant 2012C13023-1, and the Research to Prevent Blindness challenge grant to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Q.D. and L.G. designed and conceived the experiments. Q.D., R.B., D.Z., G.L, and L.G. performed the experiments. Q.D., R.B., and L.G wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sherman SM, Guillery RW, Sherman SM. Exploring the thalamus and its role in cortical function. 2nd. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; 2006. p. xxi.p. 484. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puelles L, Rubenstein JL. Forebrain gene expression domains and the evolving prosomeric model. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(9):469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puelles L, Rubenstein JL. Expression patterns of homeobox and other putative regulatory genes in the embryonic mouse forebrain suggest a neuromeric organization. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16(11):472–479. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figdor MC, Stern CD. Segmental organization of embryonic diencephalon. Nature. 1993;363(6430):630–634. doi: 10.1038/363630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee M, Li JY. Patterning and compartment formation in the diencephalon. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:66. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiecker C, Lumsden A. Hedgehog signaling from the ZLI regulates diencephalic regional identity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(11):1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/nn1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vue TY, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling controls thalamic progenitor identity and nuclei specification in mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29(14):4484–4497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0656-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong Y, et al. Spatial and temporal requirements for sonic hedgehog in the regulation of thalamic interneuron identity. Development. 2011;138(3):531–541. doi: 10.1242/dev.058917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vieira C, et al. Thalamic development induced by Shh in the chick embryo. Dev Biol. 2005;284(2):351–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein DJ. Regulation of thalamic development by sonic hedgehog. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:57. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholpp S, et al. Hedgehog signalling from the zona limitans intrathalamica orchestrates patterning of the zebrafish diencephalon. Development. 2006;133(5):855–864. doi: 10.1242/dev.02248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Q, et al. BARHL2 differentially regulates the development of retinal amacrine and ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):3992–4003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5237-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding Q, et al. BARHL2 transcription factor regulates the ipsilateral/contralateral subtype divergence in postmitotic dI1 neurons of the developing spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(5):1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112392109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T, et al. Mammalian BarH homologue is a potential regulator of neural bHLH genes. Dev Biol. 1998;199(2):216–225. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki-Hirano A, et al. Dynamic spatiotemporal gene expression in embryonic mouse thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519(3):528–543. doi: 10.1002/cne.22531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vue TY, et al. Characterization of progenitor domains in the developing mouse thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505(1):73–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt T, et al. A role for Pax6 in the normal development of dorsal thalamus and its cortical connections. Development. 2000;127(23):5167–5178. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peukert D, et al. Lhx2 and Lhx9 determine neuronal differentiation and compartition in the caudal forebrain by regulating Wnt signaling. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(12):e1001218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fode C, et al. A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes Dev. 2000;14(1):67–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyashita-Lin EM, et al. Early neocortical regionalization in the absence of thalamic innervation. Science. 1999;285(5429):906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Guo Q, Li JY. Transcription factor Gbx2 acts cell-nonautonomously to regulate the formation of lineage-restriction boundaries of the thalamus. Development. 2009;136(8):1317–1326. doi: 10.1242/dev.030510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quina LA, et al. Brn3a and Nurr1 mediate a gene regulatory pathway for habenula development. J Neurosci. 2009;29(45):14309–14322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2430-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funato H, Saito-Nakazato Y, Takahashi H. Axonal growth from the habenular nucleus along the neuromere boundary region of the diencephalon is regulated by semaphorin 3F and netrin-1. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16(3):206–220. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahay A, et al. Semaphorin 3F is critical for development of limbic system circuitry and is required in neurons for selective CNS axon guidance events. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6671–6680. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06671.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell TN, et al. Polymicrogyria and absence of pineal gland due to PAX6 mutation. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(5):658–663. doi: 10.1002/ana.10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vue TY, et al. Thalamic control of neocortical area formation in mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33(19):8442–8453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5786-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caballero IM, et al. Cell-autonomous repression of Shh by transcription factor Pax6 regulates diencephalic patterning by controlling the central diencephalic organizer. Cell Rep. 2014;8(5):1405–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeltser LM. Shh-dependent formation of the ZLI is opposed by signals from the dorsal diencephalon. Development. 2005;132(9):2023–2033. doi: 10.1242/dev.01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimamura K, et al. Longitudinal organization of the anterior neural plate and neural tube. Development. 1995;121(12):3923–3933. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao Y, et al. Cis-regulatory architecture of a brain signaling center predates the origin of chordates. Nat Genet. 2016;48(5):575–580. doi: 10.1038/ng.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juraver-Geslin HA, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Durand BC. The conserved barH-like homeobox-2 gene barhl2 acts downstream of orthodentricle-2 and together with Iroquois-3 in establishment of the caudal forebrain signaling center induced by Sonic Hedgehog. Dev Biol. 2014;396(1):107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabo NE, et al. The role of Sonic hedgehog of neural origin in thalamic differentiation in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2009;29(8):2453–2466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4524-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa Y, Shimogori T. Diversity of thalamic progenitor cells and postmitotic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(10):1554–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.