Highlights

-

•

Desmoid tumours are the second commonest tumour in FAP after colonic adenomas.

-

•

Desmoid tumours do not metastasise but are locally aggressive.

-

•

Patients with FAP should be examined regularly post-panproctocolectomy since desmoid tumours may arise.

Keywords: Desmoid, FAP

Abstract

Introduction

Desmoid tumours are locally aggressive tumours which are common in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP).

Presentation of case

A 20-year old Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) patient presented with abdominal pain and distention. Abdominal imaging showed small bowel obstruction and hydronephrosis due to a pelvic mass. This mass showed significant enlargement on repeat imaging, and a diagnostic biopsy confirmed desmoid tumour.

The mass was deemed unresectable and he was initially started on sulindac and raloxifene. Repeat imaging however showed further enlargement of the tumour, and therefore vinblastine + methotrexate chemotherapy was commenced, with a good response.

Discussion

FAP is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Gardner’s syndrome is also caused by a mutation in the APC gene, and is now considered a different phenotypic presentation of FAP. Desmoid tumours are initially kept under observation while their size remains stable. Treatment options for enlarging desmoids tumours include surgery (first-line), radiotherapy, and systemic therapy with non-cytotoxic and cytotoxic therapy.

Conclusion

FAP patients should be examined regularly post-panprocotocolectomy, since desmoid tumours may arise. The presence of epidermal cysts in this FAP patient suggests a diagnosis of Gardner’s syndrome.

1. Introduction

Desmoid tumours are the second commonest tumour in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) after colonic adenomas. Although they do not metastasise, they are often locally aggressive, and usually present with symptoms due to compression of adjacent structures, such as bowel or ureter. The authors describe the case of desmoid tumour in a Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) patient who presented with abdominal pain and distention.

2. Patient information

A 20-year old Maltese gentleman presented to the Emergency Department with a 2-day history of abdominal pain. The abdominal pain was severe, particularly over the right flank radiating to the back, and was associated with nausea and vomiting. He also complained of worsening abdominal distention, fatigue and weight loss.

The patient had a history of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), diagnosed at age 7. At the age of 18 he had a laparoscopic restorative panproctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. In late adolescence, he had two skin lumps removed from his feet, with histology showing pilomatrixoma-type features arising in a background of epidermal cyst, raising the possibility of Gardner’s syndrome.

3. Clinical findings

On examination, the patient appeared dehydrated and mildly hypotensive, with a blood pressure of 105/60 mmHg. His parameters were otherwise stable and he was afebrile. The abdomen was distended, and there was mild generalized abdominal tenderness with no rigidity or guarding. Rectal examination was within normal limits. Examination of the lower limbs revealed bilateral mild oedema, with no erythema or calf tenderness.

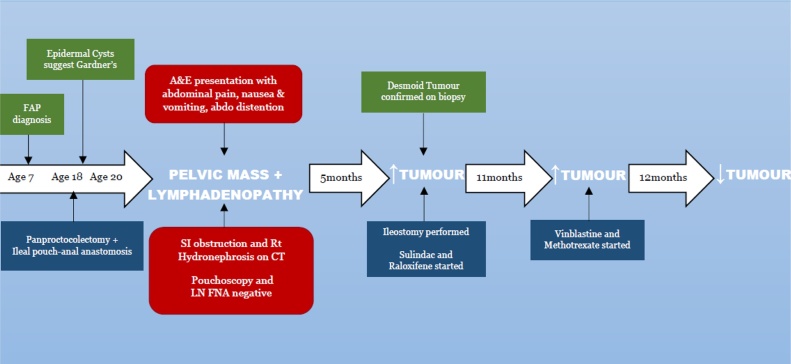

4. Timeline

5. Diagnostic assessment

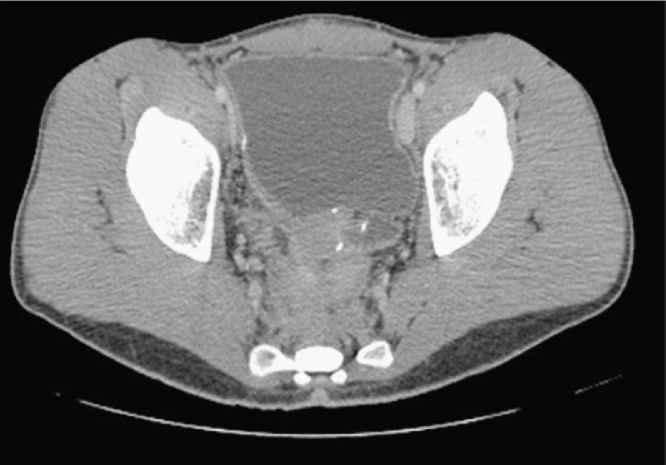

Initial investigations revealed a normal blood count and an elevated urea level. Computed Tomography (CT) showed marked small bowel distention with obstruction due to a mass in the region of the ileal pouch. The mass extended into the pre-sacral space (Fig. 1) and was associated with an enlarged iliac lymph node complex. The large mass was obstructing the lower right ureter with resultant hydroureter and hydronephrosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Dilated fluid-filled bowel with a pre-sacral mass.

Fig. 2.

Dilated bowel with air fluid levels and right sided hydronephrosis.

A right-sided ureteric stent was inserted. Pouchoscopy was attempted but the pouch was inaccessible due to a very narrow lumen. Biopsies were taken from abnormal mucosa below the pouch, and histology showed chronic colitis and an adenomatous polyp with low grade dysplasia. The patient was discharged home with close follow-up.

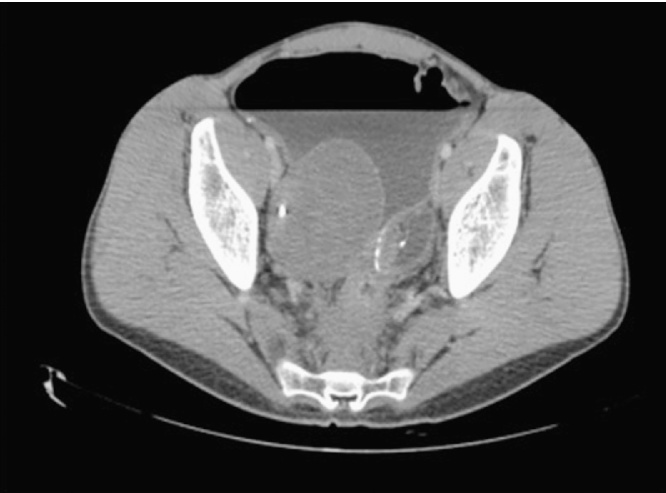

Pouchoscopy was repeated two months later and biopsies were taken from an erythematous area, with histology showing mucosal lymphoid hyperplasia with no evidence of malignancy. US-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the mesenteric lymph nodes showed no malignant cells. Repeat CT five months after presentation showed a significant enlargement of the right pelvic mass (Fig. 3). The abdominal lymphadenopathy had however decreased in size. Significant small bowel dilatation persisted (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Dilated fluid-filled bowel with an enlarging pre-sacral mass.

Fig. 4.

Severely dilated bowel with air fluid levels.

The case was discussed with the Multi-Disciplinary Team who deemed the mass to be a desmoid tumour due to the history of FAP. The enlarging desmoid tumour was causing chronic incomplete small bowel obstruction and hydronephrosis. In view of the pilomatrixoma-type features of the epidermal cysts, the patient was likely to have Gardner’s syndrome.

6. Therapeutic intervention

The patient was then transferred to St. Mark’s Hospital in Middlesex, United Kingdom for expert management. He was commenced on parenteral nutrition and underwent an explorative laparotomy whereby the tumour was deemed unresectable. A loop ileostomy was formed just proximal to the ileoanal pouch; a diagnostic biopsy taken from the presacral mass confirmed desmoid tumour. Combination non-cytotoxic anti-desmoid medication—sulindac and raloxifene—was started in view of his age and in an attempt to obtain higher response rates than achievable with monotherapy.

7. Follow-up and outcomes

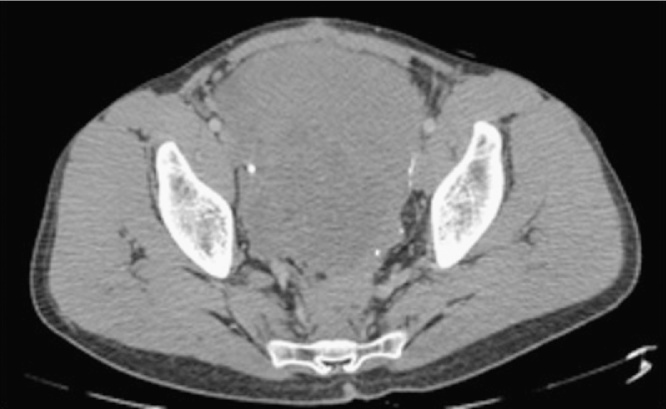

Repeat CT 12 months after presentation showed that the pelvic mass had more than doubled in size, then measuring 22 × 20 × 16 cm (Fig. 5). He was referred to Oncology at 16 months post-presentation and given the urgency posed by the rapid disease progression, cytotoxic therapy was indicated. Echocardiography showed a LVEF of 55%, and he was therefore started on weekly vinblastine + methotrexate chemotherapy in preference to an anthracycline-based regimen. After a two-month period, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed a slight reduction in the intra-abdominal mass. At four months, tumour size was stable, while it shrunken to 15 × 16 × 16 cm by 3 months after completion of the 1 year course of chemotherapy.

Fig. 5.

Enlarging pelvic mass.

8. Discussion

Desmoid tumours are rare fibromatous lesions that are non-metastasising but locally aggressive and have a high rate of recurrence even after complete resection [1], [2] These slow-growing tumours commonly arise in the abdominal wall or in the intra-abdominal region.

2% of cases of desmoid tumours are associated with FAP [1]. Whereas the incidence of desmoid tumours in the general population is 2–4 per million per year, the incidence in FAP is 10–20%, meaning that a patient with FAP is at an 852-fold increased risk of developing a desmoid tumours [2], [3], [6]. While sporadic desmoid tumours show a flight female preponderance, there is an equal incidence in males and females in FAP patients [8]. Familial aggregation is seen in FAP demois tumours, but not in sporadic cases [7].

FAP is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, on chromosome 5q21 [4]. FAP is characterized by hundreds of adenomatous colorectal polyps, with an almost inevitable progression to colorectal cancer at an average age of 35–40 years [4]. Biallelic mutations of the APC gene induces desmoid tumour formation, hence the association between these two disorders [2]. Surgical trauma has been identified as a predisposing factor for desmoid tumour formation in FAP, with one key study from 1994 noting a history of previous abdominal surgery in 68% of FAP patients with abdominal desmoids, with 55% occurring within 5 years post-operatively [7].

Gardner’s syndrome is also caused by a mutation in the APC gene. It includes extracolonic manifestations, both benign, such as osteomas, skin cysts, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigmented epithelium and desmoid tumours and malignant, such as duodenal, thyroid, pancreatic, liver and central nervous system cancers. Previously, Gardner’s syndrome used to be considered as a separate entity, but it is now considered a different phenotypic presentation of FAP [4].

Intra-abdominal desmoids are usually asymptomatic. They become symptomatic when they compress or have infiltrated surrounding viscera. This may result in intestinal obstruction, ischemic bowel secondary to vascular compression, and hydronephrosis due to ureteric compression. Desmoid tumours can also rarely lead to bowel perforation as well as deep vein thrombosis, pyrexia of unknown origin, gastrointestinal bleeding and intra-abdominal abscess formation [2].

Patients with FAP should be closely followed up regularly with abdominal examinations in order to look for any signs of tumours and obstruction [1]. CT and MRI are used to identify these tumours (and monitoring) [2] but a biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis [1]. They are initially kept under observation while their size remains sTable Surgical excision with a safety margin is the first-line treatment for enlarging desmoid tumours.

Desmoid tumours are star-shaped tumours with infilitrative growth, so complete excision entails a large resection. In the past, radical surgical resection with the goal of achieving complete excision with negative margins was standard, as for sarcomas. However whereas positive margins are a predictor of local failure in the case of sarcomas, this was not shown consistently for desmoid tumours, as indolent desmoid tumours will not recur regardless of margin positivity. Therefore radical surgery for all demoid tumours may lead to unnecessary morbidity. Studies have shown that patients with poor prognosis desmoid tumours would benefit most from clear surgical resection margins, and the extent of surgery now depends on the biology of tumour, with function-sparing surgery that does not leave macroscopic residual disease being the treatment of choice in many cases [9]. Recurrence rates after surgery range from 60 to 85%, hence highlighting the importance of regular follow-up and monitoring [2].

Radiotherapy is considered for patients who are not good surgical candidates, or when there remains gross residual disease postoperatively. Systemic therapy is used at relapse; non-cytotoxic drugs are used first-line in situations of acceptably low risk, while cytotoxic chemotherapy is indicated at disease progression or in clinically urgent situations. Non-cytotoxic options include anti-oestrogens (e.g. tamoxifen), prostaglandin inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and imatinib [2], [5]. Possible chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced desmoid tumours include doxorubicin + dacarbazine, liposomal doxorubicin, vinblastine + methotrexate, vinorelbine + methotrexate and vincristine + actinomycin-D + cyclophosphamide [5].

Prognosis depends on the stage of desmoid tumours (I to IV) with five-year survival being 95% at Stage 1 (asymptomatic, <10 cm maximum diameter, and not growing) and 76% at Stage IV (severely symptomatic, or >20 cm, or rapidly growing) [10], [11].

9. Patient perspective

The patient described an initial period of anxiety until a definitive diagnosis was reached, and when disease progression was initially noted. Once cytotoxic therapy was started and repeat imaging showed stable disease, the patient felt more comfortable and content.

10. Conclusion

Since desmoid tumours are common in FAP, patients should be examined regularly post-panprocotocolectomy for any signs suggesting the presence of intra-abdominal desmoid tumours. The patient most likely had a diagnosis of Gardner’s syndrome, as suggested by the epidermal cysts. This is a distinctive phenotype of FAP, and the presence of desmoid tumours is well-documented. The patient was initially treated with non-cytotoxic therapy, however cytotoxic therapy was started at disease progression. Vinblastine + methotrexate combination therapy had a good response.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Nill.

Ethical approval

Not relevant.

Consent

Not relevant since there are no identifying images.

Author contribution

Sarah Xuereb is the corresponding author. She is a final year medical student at University of Malta Medical School, and she was responsible for the writing of the case report together with Rachel Xuereb and Chiara Buhagiar, final year medical students at the University of Malta Medical School. Jonathan Gauci is a Higher Specialist Trainee in Respiratory and General Medicine who was responsible for the care of the patient while training at Sir Anthony Mamo Oncology Centre, Mater Dei Hospital, and was involved in the writing of the case report. Claude Magri is a Consultant in Clinical Oncology at Sir Anthony Mamo Oncology Centre, Mater Dei Hospital who was responsible for the primary care of the patient from the Oncology aspect, and supervised the writing of this case report.

Guarantor

Sarah Xuereb, Rachel Xuereb, Chiara Buhagiar, Jonathan Gauci, Claude Magri.

Contributor Information

Sarah Xuereb, Email: sarahxuereb94@gmail.com.

Rachel Xuereb, Email: rachel.xuereb94@gmail.com.

Chiara Buhagiar, Email: chiarabuhagiar@gmail.com.

Jonathan Gauci, Email: jonathangauci88@gmail.com.

Claude Magri, Email: claude.magri@gov.mt.

References

- 1.Leal R.F., Tapia Silva P.V.V., Setsuko Ayrizono M.L., Fagunes J.J., Amstalden E.M.I., Rodrigues Coy C.S. Desmoid tumor in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2010;47(4):373–378. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032010000400010. ISSN 0004-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moraes Righetti A.E., Jacomini C., Serafim Parra R., Normanha Riberiro de Almeida A.L., Ribeiro Rocha J.J., Féres O. Familial adenomatous polyposis and desmoid tumors. Clinics. 2011;66(10):1839–1842. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez Garcia E.B., Knoers N.V. Gardner’s syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis): a cilia-related disorder. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(7):727–735. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escobar C., Munker R., Thomas J.O., Li B.D., Burton G.V. Update on desmoid tumours. Ann. Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAdam W.A., Goligher J.C. The occurrence of desmoids in patients with familial polyposis coli. Br3 Surg. 1970;57:618–631. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800570816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurbuz A.K., Giardiello F.M., Petersen G.M., Krush A.J., Offerhaus G.J., Booker S.V., Kerr M.C., Hamilton S.R. Desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut BMJ. 1994;35(3):377–381. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah M., Azam B. Case report of an intra-abdominal desmoid tumour presenting with bowel perforation. McGill J. Med. 2007;10(2):90–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonvalot S., Desai A., Coppola S., Le Péchoux C., Terrier P., Dômont J., Le Cesne A. The treatment of desmoid tumours: a stepwise clinical approach. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl. 10) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasper B., Ströbel P., Hohenberger P. Desmoid tumors: clinical features and treatment options for advanced disease. Oncologist. 2011;16(May (5)):666–682. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quintini C., Ward G., Shatnawei A., Xhaja X., Hashimoto K., Steiger E., Hammel J., Diago Uso T., Burke C.A., Church J.M. Mortality of intra-abdominal desmoid tumours in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: a single center review of 154 patients. Ann. Surg. 2012;255(3):511–516. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824682d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church J., Lynch C., Neary P., LaGuardia L., Elayi E. A desmoid tumour-staging system separates patients with intra-abdominal, familial adenomatous polypsis-associated desmoid disease by behaviour and prognosis. ACRCS. 2008;51:897–901. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]