Abstract

Species belonging to Aspergillus section Cervini are characterised by radiate or short columnar, fawn coloured, uniseriate conidial heads. The morphology of the taxa in this section is very similar and isolates assigned to these species are frequently misidentified. In this study, a polyphasic approach was applied using morphological characters, extrolite data, temperature profiles and partial BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequences to examine the relationships within this section. Based on this taxonomic approach the section Cervini is resolved in ten species including six new species: A. acidohumus, A. christenseniae, A. novoguineensis, A. subnutans, A. transcarpathicus and A. wisconsinensis. A dichotomous key for the identification is provided.

Key words: Ascomycetes, Eurotiales, Extrolites, Multi-gene phylogeny, Subgenus Fumigati

Taxonomic novelties: Aspergillus acidohumus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. christenseniae A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. novoguineensis A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. subnutans A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. transcarpathicus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson; A. wisconsinensis A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson

Introduction

The section Cervini (Gams et al. 1985) of the genus Aspergillus includes species with radiate or short columnar, fawn coloured, uniseriate conidial heads. Phylogenetic analysis of multilocus sequence data showed that section Cervini belongs to Aspergillus subgenus Fumigati together with sections Fumigati and Clavati (Peterson, 2008, Peterson et al., 2008).

Christensen et al. (1964) assigned four species to this section: A. cervinus, A. kanagawaensis, A. nutans and A. parvulus. Based on morphological similarities Samson (1979) proposed that A. bisporus described by Kwon-Chung & Fennell (1971) also belongs to section Cervini. However, molecular studies revealed that A. bisporus is distantly related to this section, and belongs to subgenus Nidulantes, section Bispori (Peterson 2000, Peterson, 2008, Peterson et al., 2008, Chen et al., 2016). Udagawa et al. (1993) described A. vinosobubalinus in Japan belonging to this section and until now only five species are reported. Isolates assigned to section Cervini are frequently misidentified because they are morphologically similar.

Members of section Cervini are economically less important and not well-studied. Aspergillus cervinus has originally been isolated from African soil (Massee 1914), later it was also found in soil in New Zealand (Neill, 1939, di Menna et al., 2007), Malaysia and USA (Christensen and Fennell, 1964, Christensen et al., 1964). This taxon was found to produce the quinol derivative terremutin and 3,6-dihydroxy-2,5-toluquinone (Elsohly et al. 1974). These authors stated that while the compound terremutin showed a relationship with A. terreus, 3,6-dihydroxy-2,5-toluquinone indicated a relationship to A. fumigatus. Aspergillus kanagawaensis was originally isolated from soil in Japan (Nehira 1951) and later also found in soil in Wisconsin, USA (Christensen et al. 1964), Ukraine and Russia (Ushakova et al., 1974, Buiak et al., 1978), and on oak stumps in Poland (Kwasna 2001). This species secretes a range of proteases which have been studied in detail (Ushakova et al., 1974, Buiak et al., 1978, Landau et al., 1980), and also exhibits entomopathogenic properties against mosquito larvae (de Moraes et al. 2001). Aspergillus parvulus was originally isolated from soil in USA (Smith 1961), but also identified in feed ingredients in Argentina (Magnoli et al. 1998). This species has been found to exhibit a wide spectrum of antibiotic activities against a range of bacteria (Tsyganenko & Zaichenko 2004a), and phytotoxic activities (Tsyganenko & Zaichenko 2004b). This species has been found to produce parvulenone (Chao et al. 1979), naphthalenone (Bartman & Campbell 1979) and asparvenone derivatives (Bös et al. 1997). Aspergillus nutans was originally found in soil in Australia (McLennan et al. 1954), later in soil in Wisconsin, USA and South Africa (Christensen et al., 1964, Wicklow and Whittingham, 1974), it was also reported to produce terremutin (Phoebe et al. 1978). Aspergillus vinosobubalinus was isolated from a sweet flag bed in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan (Udagawa et al. 1993) and it is characterised by sectional features as pinkish fawn, radiate, uniseriate conidial heads. However the ex-type culture CBM BF-33501 is unavailable for the further examination. Species of section Cervini have not been found to be important human pathogens, however Hubka et al. (2012) reported an isolate (closely related to A. parvulus) as the possible cause of human onychomycosis.

In this study, we examined the available isolates of the species belonging to Aspergillus section Cervini to clarify their taxonomic status. The methods used include phylogenetic analysis using internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), β-tubulin (BenA), calmodulin (CaM) and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2), macro- and micro-morphological analysis, examination of temperature and extrolite profiles.

Materials and methods

Fungal strains

Strains used in this study were obtained from CBS, CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands; IBT, culture collection of the DTU Systems Biology, Lyngby, Denmark; CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre, Beijing, China and DTO, working collection of the Applied and Industrial Mycology department housed at CBS-KNAW. An overview of strains is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study.

| Species | Strain no. | Source | GenBank accession nr. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 | |||

| Aspergillus acidohumus | CBS 141577T = CGMCC3.18217 = DTO 340-H1 = IBT 34346 | Acid soil, Guizhou, China | KX423646 | KX423623 | KX423634 | KX423663 |

| A. cervinus | CBS 537.65T = DTO 054-D5 = ATCC 16915 = IBT 22087 = IMI 126542 = NRRL 5025 = QM 8875 = WB 5025 | Soil, tropical rain forest, near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | EF661268 | EF661251 | EF661261 | EF661229 |

| CBS 196.64 = ATCC 15508 = IMI 107684 = NRRL 3157 = IBT 22044 = WB 5026 | Soil, tropical rain forest, near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | EF661270 | EF661250 | EF661260 | EF661228 | |

| A. christenseniae | CBS 122.56T = DTO 022-C8 = IBT 22043 = IBT 23735 = IMI 343732 = NRRL 4897 = WB 4897 | Soil, Rietvlei, Pretoria, South Africa | FJ491613 | FJ491639 | FJ491608 | EF661235 |

| CBS 411.64 = IBT 22076 | Soil under Quercus sp., Wisconsin, USA | FJ491615 | FJ491642 | FJ491607 | – | |

| CBS 122715 = DTO 022-A8 = DTO 349-F2 = IBT 29311 | Soil, Atherton Tableland near little Malgrave, Queensland, Australia | FJ491612 | FJ491644 | FJ491594 | KX423664 | |

| A. kanagawaensis | CBS 538.65T = DTO 054-F3 = ATCC 16143 = IBT 22077 = IFO 6219 = IMI 126690 = NRRL 4774 = WB 4774 | Soil, Kanagawa, Japan | FJ491617 | FJ491640 | FJ491597 | JN121531 |

| NRRL 35642 = DTO 069-D6 = IBT 34350 | Upland hardwood forest soil, Sumter County, Georgia, USA | EF661276 | EF661240 | EF661264 | EF661237 | |

| CBS 129333 = DTO 202-A5 = IBT 34351 | Unknown | KX423647 | KX423624 | KX423637 | KX528452 | |

| A. novoguineensis | CBS 906.96T = DTO 021-G5 = IBT 29312 | Humus, Papua New Guinea | FJ491622 | FJ491641 | FJ491605 | KX423681 |

| A. nutans | CBS 121.56T = DTO 054-D3 = NRRL 575 = NRRL 4364 = NRRL A–6280 = ATCC 16914 = IFO 8134 = IMI 062874ii = IMI 62874 = QM 8159 = WB 4364 = WB 4546 = WB 4776 | Soil, Australia | EF661272 | EF661249 | EF661262 | EF661227 |

| CBS 122714 = DTO 349-F1 = IBT 29313 | Soil, Barron Falls, Australia | FJ491614 | FJ491630 | FJ491600 | KX423665 | |

| A. parvulus | CBS 136.61T = DTO 021-G8 = IBT 22085 = ATCC 16911 = IMI 086558 = LSHB BB405 = NRRL 1846 = NRRL 4753 = QM 7955 = UC 4613 = WB 4753 | Forest soil, USA | EF661269 | EF661247 | EF661259 | EF661233 |

| CBS 412.64 = NRRL 5023 = WB 5023 | Soil under Pinus banksiana, Wisconsin, USA | EF661274 | EF661246 | EF661256 | EF661231 | |

| CBS 262.67 = IBT 22079 | Agricultural soil, Mansholtlaan, Wageningen, the Netherlands | KX423653 | FJ491628 | FJ491599 | KX423668 | |

| CBS 298.71 = IBT 22088 = IMI 151275 | Soil, North Carolina, USA | FJ491616 | FJ491635 | FJ491602 | KX423670 | |

| CBS 123897 = NRRL 4220 = IBT 22039 = DTO 070-A4 | Jackpine (Pinus banksiana) coniferous forest soil, Wisconsin, USA | KX423657 | KX423625 | KX423638 | KX423666 | |

| CBS 133109 = IBT 22046 = WB 4994 = DTO 070-A1 = NRRL A-3096 | Pine forest soil, Scotland, UK | EF661267 | EF661248 | EF661257 | EF661232 | |

| DTO 189-G7 = IBT 34355 | Soil, the Netherlands | KX423654 | KX423627 | KX423639 | – | |

| CBS 133098 = NRRL 2667 = NRRL 5028 = IBT 22045 = WB 5028 | Soil, Georgia, USA | EF661271 | EF661244 | EF661258 | EF661234 | |

| A. subnutans | CBS 129386T = DTO 202-C2 = WSF 445 = IBT 34352 | Soil under Tsuga canadensis, Wisconsin, USA | KX528456 | KX528454 | KX528455 | KX528453 |

| A. transcarpathicus | CBS 423.68T = DTO 022-C7 = IBT 22080 = IMI 134108 = VKM F-1331 | Transcarpathia, Ukraine | FJ491624 | FJ491632 | FJ491610 | KX423680 |

| CBS 410.64 = IBT 22086 = UPSC 3141 = WSF 5750 | Sandy soil, of Salix nigra community, Wisconsin, USA | FJ491611 | FJ491643 | FJ491593 | KX423678 | |

| CBS 424.68 = IBT 22081 | Forest soil, Zacarpathian region, Ukraine | FJ491626 | FJ491631 | FJ491603 | KX423679 | |

| A. wisconsinensis | CBS 413.64T = DTO 022-B1 = NRRL 5027 = IBT 22042 = IBT 22082 = WSF 380 = DTO 070-A5 = WB 5027 | Soil under Tsuga canadensis, Wisconsin, USA | FJ491618 | FJ491638 | FJ491609 | KX423671 |

| CBS 129387 = DTO 202-C3 = IBT 34347 | Soil, Wisconsin, USA | KX423649 | KX423633 | KX423641 | KX423673 | |

| CBS 129400 = DTO 202-D7 = IBT 34348 | Soil, Wisconsin, USA | KX423652 | KX423630 | KX423643 | KX423674 | |

| CBS 126265 = DTO 195-E2 = IBT 34346 | Soil, Stephen Foster State Park, Florida, USA | KX423651 | KX423632 | KX423644 | KX423675 | |

| CBS 127024 = DTO 196-F2 = IBT 34349 | Soil under Tsuga canadensis, Wisconsin, USA | KX423648 | KX423629 | KX423645 | KX423672 | |

| CBS 123896 = NRRL 2161 = IBT 22041 = DTO 070-A3 | Soil, Australia | KX423656 | KX423628 | KX423640 | KX423676 | |

Morphological examinations

Macroscopic characters were studied on Czapek Yeast Autolysate agar (CYA), CYA supplemented with 5 % NaCl (CYAS), Yeast Extract Sucrose agar (YES), Creatine Sucrose agar (CREA), Dichloran 18 % Glycerol agar (DG 18), Oatmeal agar (OA) and Malt Extract agar (MEA, Oxoid malt) (Samson et al. 2010). To enhance the growth, the ex-type culture of A. acidohumus CBS 141577, isolated from acid soil from China, was additionally inoculated on Cherry Decoction agar (CHA) (Crous et al. 2009). The isolates were inoculated at three points on 90 mm Petri dishes and incubated for 7 d at 25 °C in darkness. In addition, CYA and MEA plates were incubated at 30 °C and 37 °C. After 7 d of incubation, colony diameters were recorded. The colony texture, degree of sporulation, obverse and reverse colony colours, the production of soluble pigments and exudates were determined. Light microscope preparations were made from 1 wk old colonies grown on MEA. Lactic acid (60 %) was used as mounting fluid. Ethanol (96 %) was used to remove excess conidia and prevent air bubbles. A Zeiss Stereo Discovery V20 dissecting microscope and Zeiss AX10 Imager A2 light microscope equipped with Nikon DS-Ri2 cameras and software NIS-Elements D v4.50 were used to capture digital images.

Analysis for secondary metabolites

The cultures were analysed according to the HPLC-diode array detection method of Frisvad and Thrane, 1987, Frisvad and Thrane, 1993 as modified by Smedsgaard (1997). The isolates were analysed on CYA and YES agar using three agar plugs (Smedsgaard 1997). The secondary metabolite production was confirmed by identical UV spectra with those of standards and by comparison to retention indices and retention times in pure compound standards.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Strains were grown for 1 wk on MEA prior to DNA extraction. DNA was extracted using the Ultraclean™ Microbial DNA isolation Kit (MoBio, Solana Beach, U.S.A.) and the extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C. The ITS and parts of the BenA, CaM, and RPB2 genes were amplified and sequenced using methods previously described (Houbraken and Samson, 2011, Samson et al., 2014).

Data analysis

Sequence alignments were generated with MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh & Standley 2013). The most suitable substitution model was determined based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) using FindModel (Posada & Crandall 1998). Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses including 500 bootstrap replicates were run using RAxML BlackBox web-server (Gamma model of rate heterogeneity) (Stamatakis et al. 2008). Bayesian analyses were performed with MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003). A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm of four chains was initiated in parallel from a random tree topology with a heating parameter set at 0.2. The MCMC analyses lasted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies were below 0.01. The sample frequency was set to 100 and the first 25 % of trees were removed as burn-in. Aspergillus fumigatus (CBS 133.61T) was chosen as outgroup. The resulting trees were obtained with FigTree v1.4.2 and annotated using Adobe Illustrator CS5. Bayesian inference (BI) posterior probabilities (pp) values and bootstrap (bs) percentages of ML analysis are labelled at the nodes. Values less than 0.95 pp and less than 70 % bs are not shown. Branches with values more than 1 pp and 95 % bs are thickened. Newly obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank.

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic and morphological species recognition

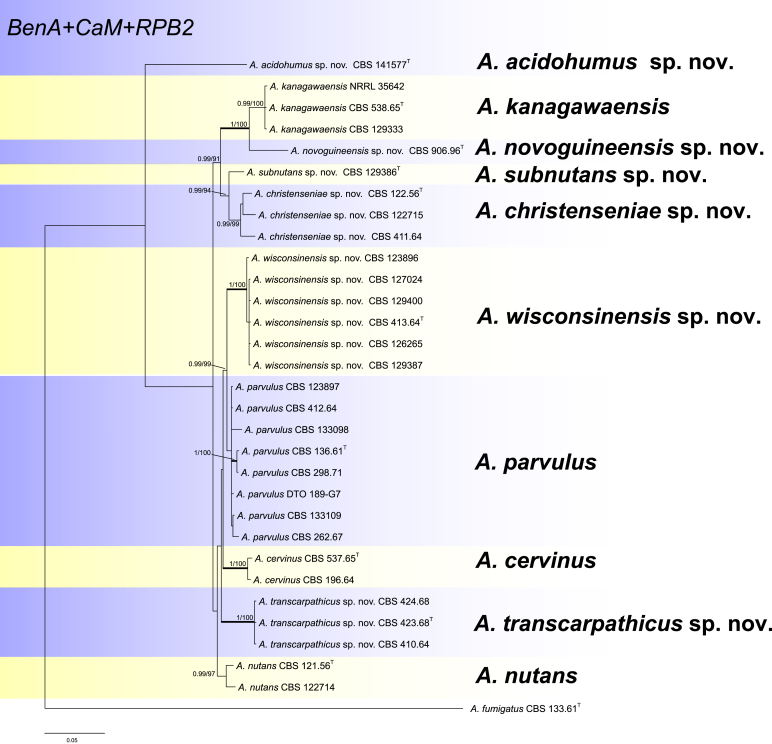

The ITS sequences of section Cervini isolates do not contain sufficient variation for distinguishing the species. Aspergillus acidohumus is the only member that can be identified using ITS sequence, A. cervinus, A. kanagawaensis, A. novoguineensis, A. nutans, A. parvulus, A. transcarpathicus and A. wisconsinensis share identical ITS sequences, while A. subnutans, A. christenseniae show small difference with these seven species (99.8 % similarity, 427/428 bp). Therefore we examined the genetic relatedness using concatenated sequence data of three loci, BenA, CaM and RPB2, the aligned data set had a total length of 1 722 bp (BenA, 411 bp; CaM, 434 bp and RPB2 867 bp). The Maximum likelihood analyses including 500 bootstrap replicates were run using RAxML. For Bayesian analyses, the Kimura 2-parameter with gamma distributed (K2P+G) model was used for BenA and RPB2, while the General time reversible with gamma distributed (GTR+G) model was used for CaM. Based on multi-gene phylogenetic analysis, ten different clades are identified in Aspergillus section Cervini (Fig. 1). Four of these, A. cervinus, A. parvulus, A. nutans, A. kanagawaensis, have been described previously, while six others represent new species.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of section Cervini inferred from concatenated loci (BenA, CaM and RPB2). Branches with values more than 1 pp and 95 % bs are thickened. The phylogram is rooted with Aspergillus fumigatus (CBS 133.61T).

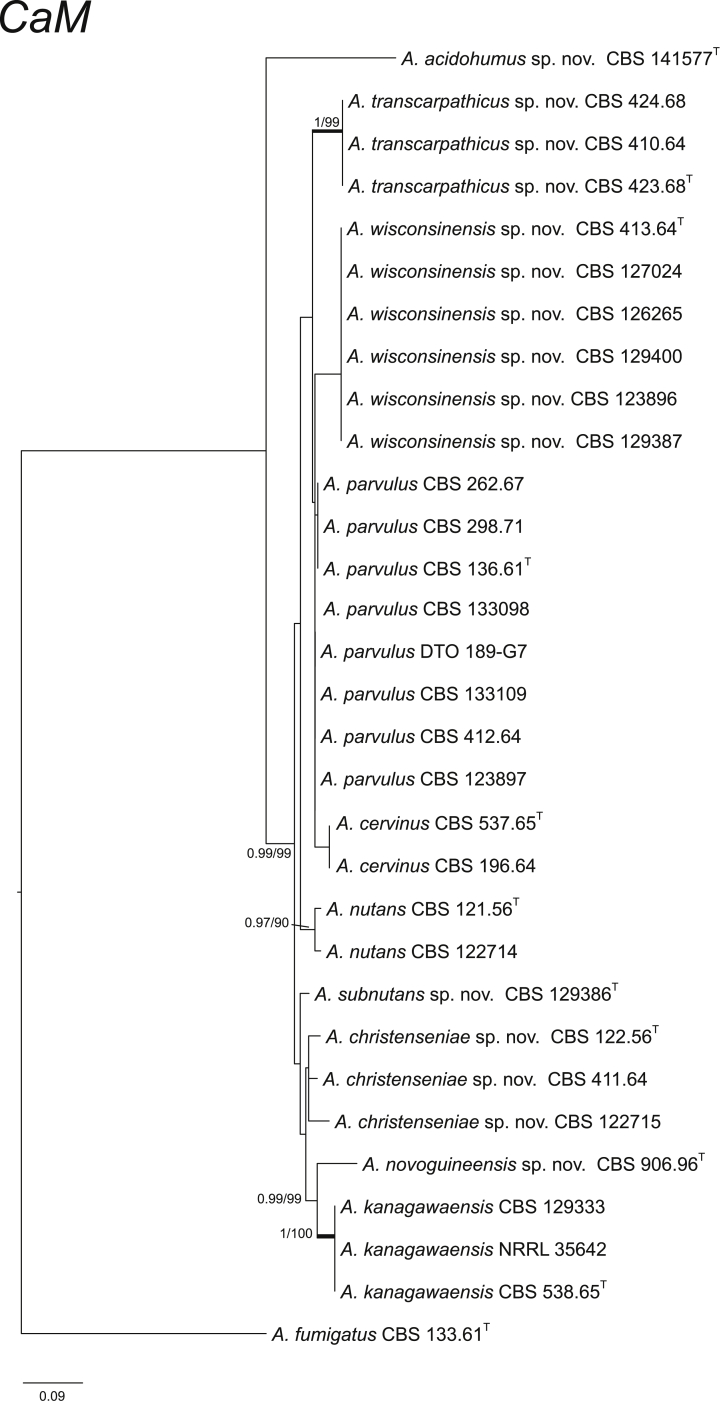

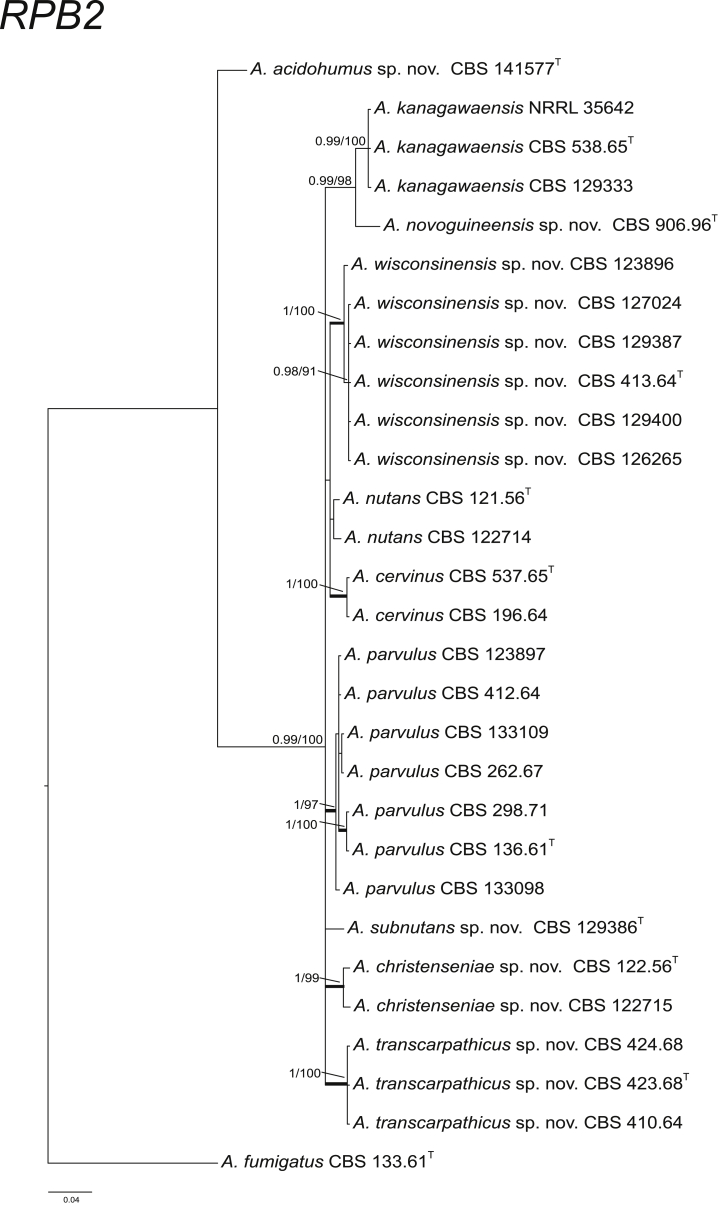

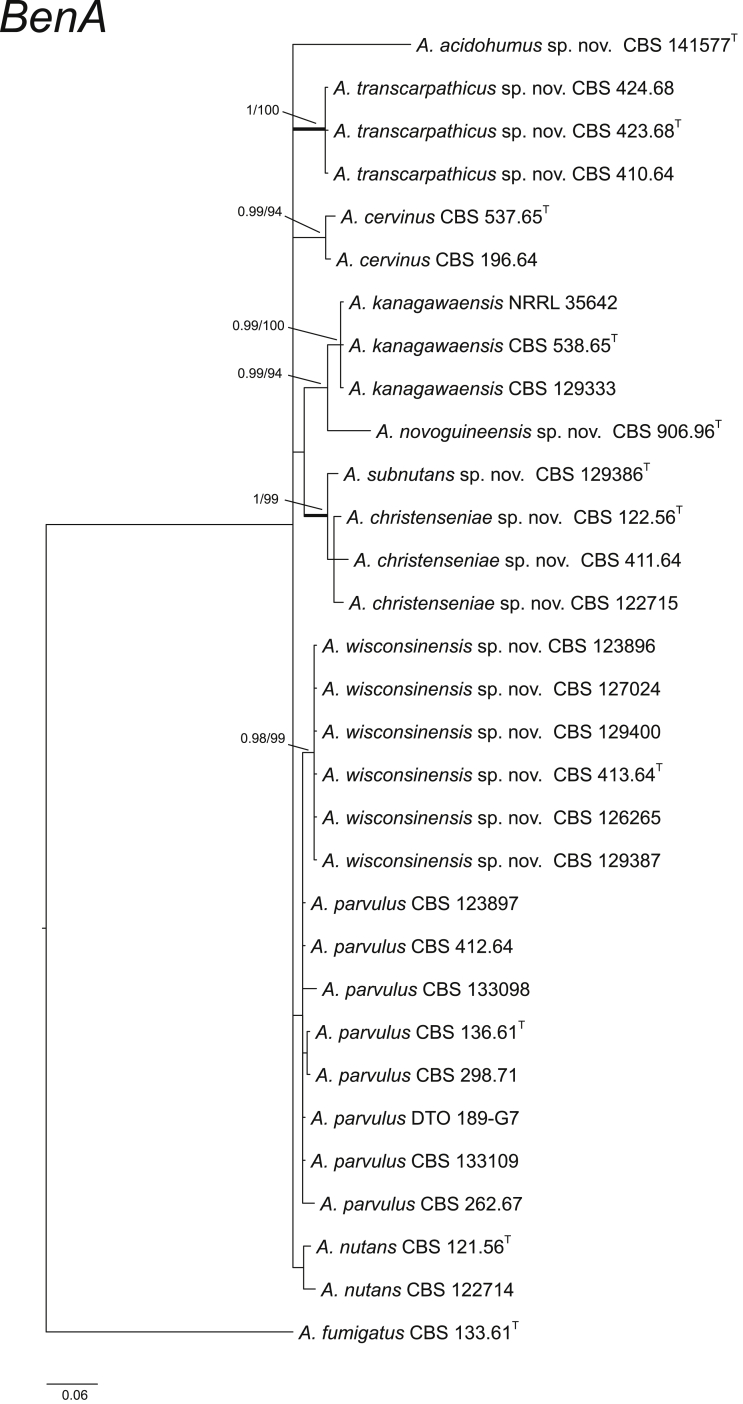

CaM performs well as the secondary identification maker for the identification of Aspergillus strains (Peterson, 2008, Samson et al., 2014). In section Cervini, all the ten species treated here have unique CaM sequences (Fig. 2). The BenA and RPB2 data sets resulted in similar species delimitation (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of section Cervini inferred from CaM. Branches with values more than 1 pp and 95 % bs are thickened. The phylogram is rooted with Aspergillus fumigatus (CBS 133.61T).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of section Cervini inferred from RPB2. Branches with values more than 1 pp and 95 % bs are thickened. The phylogram is rooted with Aspergillus fumigatus (CBS 133.61T).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of section Cervini inferred from BenA. Branches with values more than 1 pp and 95 % bs are thickened. The phylogram is rooted with Aspergillus fumigatus (CBS 133.61T).

Peterson (2008) studied the phylogenetic relationships within Aspergillus based on BenA, CaM, ITS, LSU rDNA (ID) and RPB2, and found that section Cervini formed a sister clade to sections Fumigati and Clavati. The section Cervini branch contained the four species placed in the group by Raper and Fennel (1965) and two additional lineages. These two lineages are also well resolved in our phylogeny, lineage NRRL 4897 (= CBS 122.56) together with other two strains (CBS 411.64 and CBS 122715) are described as A. christenseniae sp. nov., while lineage NRRL 2161 (= CBS 123896) and NRRL 5027 (= CBS 413.64) together with other four strains (CBS 127024, CBS 129387, CBS 126265 and CBS 129400) are described as A. wisconsinensis sp. nov.

Phylogenetically related species have morphological similarities, but there are some exceptions in section Cervini. For example, A. parvulus is phylogenetically related to A. wisconsinensis, A. cervinus and A. transcarpathicus, but morphologically this species has short conidiophores (< 100 μm) which resemble A. nutans, A. christenseniae and A. subnutans (Table 2). Aspergillus wisconsinensis, A. cervinus and A. transcarpathicus are phylogenetically and phenotypically closely related. These three species share the character of 100–300 μm long conidiophores, but there are small morphological differences within these three species. Thus CaM sequence analysis is recommended to facilitate species identification. Aspergillus kanagawaensis and A. novoguineensis form a well-supported lineage (100 % ML, 1 pp, Fig. 1). These two species produce extremely variable but long (100–800 μm) conidiophores and they differ from each other by the growth profile at high temperature; A. kanagawaensis grows on CYA and MEA at 37 °C, while A. novoguineensis does not grow or grows restrictedly under the same condition (Table 2).

Table 2.

Most important morphological characters for species recognition in Aspergillus section Cervini.

| Species | Macromorphology (7 d, in mm) |

Micromorphology |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYA 25 °C | CYA 30 °C | CYA 37 °C | MEA 25 °C | MEA 30 °C | MEA 37 °C | Conidial heads | Conidiophores | Vesicles | Phialides | Conidia | |

| Aspergillus acidohumus | Weak growth | No growth | No growth | 18–19 | 16–17 | No growth | Radiate | 40–85 (–140) × 6.5–8.5 | Globose, 17–23 | 5–6.5 × 2–2.5 | Globose, 3.5–4.5 |

| A. cervinus | 26–27 | 25–26 | No growth | 59–60 | 58–60 | No growth | Radiate | 100–300 × 5–8 | Globose, 15–20 | 5–6.5 × 2.5–3.5 | Globose, 2.5–4 |

| A. christenseniae | 20–29 | 15–25 | No growth | 42–55 | 37–52 | No or weak growth | Short columnar | 8–45 × 3.5–5.5 | Subclavate, 8–10.5 | 3.5–5 × 2–3.5 | Subglobose to ellipsoidal, 4–4.5 × 3–3.5 |

| A. kanagawaensis | 17–20 | 20–24 | 10–14 | 45–55 | 51–62 | 14–25 | Radiate | 100–800 × 5–7.5 | Globose, 20–25 | 5.5–7.5 × 3–3.5 | Globose, 2.5–3.5 |

| A. novoguineensis | 20–21 | 19–21 | No growth | 37–39 | 40–43 | No or weak growth | Radiate | 210–550 × 5–7 | Globose, 18–26 | 5–8 × 2.5–3.5 | Globose, 2.5–3.5 |

| A. nutans | 15–16 | 17–19 | Weak growth | 38–42 | 46–47 | 6–8 | Short columnar | 25–80 × 2–4 | Subclavate, 5–10 | 3.5–6 × 2–3 | Globose, 2.5–3.5 |

| A. parvulus | 22–23 | 23–24 | No growth | 35–46 | 50–51 | 5–6 | Radiate | 17–75 × 2.5–3.5 | Mainly globose, sometimes subclavate, 5–11 | 4–7 × 2–3 | Globose, 2.5–4 |

| A. subnutans | 17–18 | 17–18 | 4–6 | 34–35 | 32–33 | 10–11 | Short columnar | 25–50 × 3.5–5 | Subclavate, 7–13 | 5.5–7 × 2.5–3 | Globose, 3–4 |

| A. transcarpathicus | 14–20 | 11–24 | 4–10 | 44–60 | 37–60 | 12–18 | Radiate | 100–150 × 5.5–7.5 | Globose, 15–20 | 4.5–6.5 × 2.5–3 | Globose, 3–4 |

| A. vinosobubalinus1 | 85 | 63–64 | Radiate, splitting into columns in age | 550–1 200 × 10–12.5 | Globose to elongate, 30–45 | 5–7.5 (–10) × 2.5–3 (–5) | Globose to subglobose, 3–4.5 × 3–4 | ||||

| A. wisconsinensis | 13–17 | 11–16 | No growth | 51–53 | 40–43 | No growth | Radiate | 100–200 × 4–7 | Subclavate to globose, 14–20 | 5–7 × 2.5–3.5 | Globose, 3–4.5 |

Data derived from Udagawa et al. (1993).

Aspergillus nutans is resolved in a separate branch and morphologically it resembles A. christenseniae and A. subnutans. All of these three species produce short conidiophores; A. christenseniae is characterised by subglobose to ellipsoidal conidia, while A. subnutans has upright and uncoloured conidial heads instead of strongly pigmented, nodding heads in A. nutans. Aspergillus acidohumus, isolated from acid soil from China, occupies a basal position in section Cervini without statistical support. This species grows very restrictedly on MEA, CYA, YES and OA. It grows better on CHA media (pH 4.7), but not on CREA, CYAS and DG 18. The species is characterised by extremely compact orange brown conidial heads and tightly connected conidia which have not been observed in other species of section Cervini.

Extrolites

Isolates of Aspergillus species usually produce a diverse range of secondary metabolites that are characteristic of the different sections of Aspergillus. In many cases extrolite profiles are species specific, which are very useful in identification of unknown species (Frisvad et al., 2004, Frisvad et al., 2011, Frisvad & Larsen 2015, Varga et al., 2011, Samson et al., 2014).

An overview of extrolites produced by Cervini species is provided in Table 3. Based on our results and other studies, several species in Aspergillus section Cervini produce terremutin, a precursor of the antibiotically active extrolite terreic acid (Guo et al., 2014, Sharma et al., 2016). Producers of terremutin include A. parvulus, A. nutans, A. cervinus, A. transcarpathicus, A. novoguineensis and A. christenseniae, and were formerly identified as the two first mentioned species (Elsohly et al., 1974, Phoebe et al., 1978). Since the soil-borne species A. terreus produces terremutin and terreic acid, it seems reasonable to speculate that terreic acid is an important antibiotic agent in soil, as members of Aspergillus section Cervini are also soil-borne. Soil-borne isolates of A. fumigatus are also known to produce fumigatin oxide, a compound very similar to terreic acid (Frisvad et al. 2009), indicating a relationship of section Cervini to section Fumigati. Another metabolite indicating the relationship to section Terrei is territrems, produced by A. terreus (Ling et al., 1984, Nong et al., 2014). The compound is reported here for the first time in A. wisconsinensis in section Cervini. The territrems are related to the heteroisoextrolites pyripyropens from section Fumigati (Frisvad and Larsen, 2015, Frisvad and Larsen, 2016).

Table 3.

An overview of extrolites produced by section Cervini species.

| Species | Extrolites |

|---|---|

| Aspergillus acidohumus | No extrolites detected |

| A. cervinus | Terremutin, dihydroxy-2,5-toluquinone, cf. xanthocillin, sclerin |

| A. christenseniae | Cf. 4-hydroxymellein, terremutin, orange-red anthraquinone, cf. chlorflavonin |

| A. kanagawaensis | Few extrolites (two polar indol-alkaloids, one polar indol-alkaloid) |

| A. novoguineensis | An asparvenone, sclerotigenin, terremutin |

| A. nutans | Terremutin, some carotenoid-like extrolites |

| A. parvulus | Asparvenones, parvulenones, 6-ethyl-7-methoxyjuglone, cf. cycloaspeptide, terremutin, some carotenoid-like extrolites, cf. 4-hydroxymellein, orange-red anthraquinone |

| A. subnutans | Cf. 4-hydroxymellein |

| A. transcarpathicus | Asparvenones, terremutin, cf. 4-hydroxymellein, cf. xanthocillin |

| A. wisconsinensis | An asparvenone, cf. 4-hydroxymellein, sclerotigenin, two territrems, cf. cycloaspeptide |

A strain identified as A. cervinus was reported to produce penicillic acid, 4R*,5S*-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-5-methylcyclohex-2-enone and 6-methoxy-5-dihydropenicillic acid (He et al. 2004). Unfortunately this strain is not available for study, but it may also be misidentified and be a member of Aspergillus section Circumdati containing several known producers of penicillic acid (Visagie et al. 2014).

The isolation of the antiinsectan extrolite sclerotigenin from A. novoguineensis and A. wisconsinensis is the first report of this compound from Aspergillus, as it was first found in Penicillium species (Joshi et al., 1999, Larsen et al., 2000). However the similar heteroisoextrolite auranthine was isolated from A. lentulus in section Fumigati (Larsen et al. 2007), again showing some chemosystematic similarities to section Fumigati.

The asparvenones are produced by A. parvulus, A. transcarpathicus, A. novoguineensis and A. wisconsinensis. These compounds have also been isolated from the unrelated fungi Botrysphaeria australis (Xu et al. 2011) and a Kirschsteinothelia species (Poch et al. 1992). One of the asparvenones (Chao et al., 1975, Chao et al., 1976, Chao et al., 1979), O-methylasparvenone, has been reported to be a serotonin antagonist (Bös et al. 1997). The asparvenones also have other promising biomedical properties (Poch et al., 1992, Xu et al., 2011).

Taxonomy

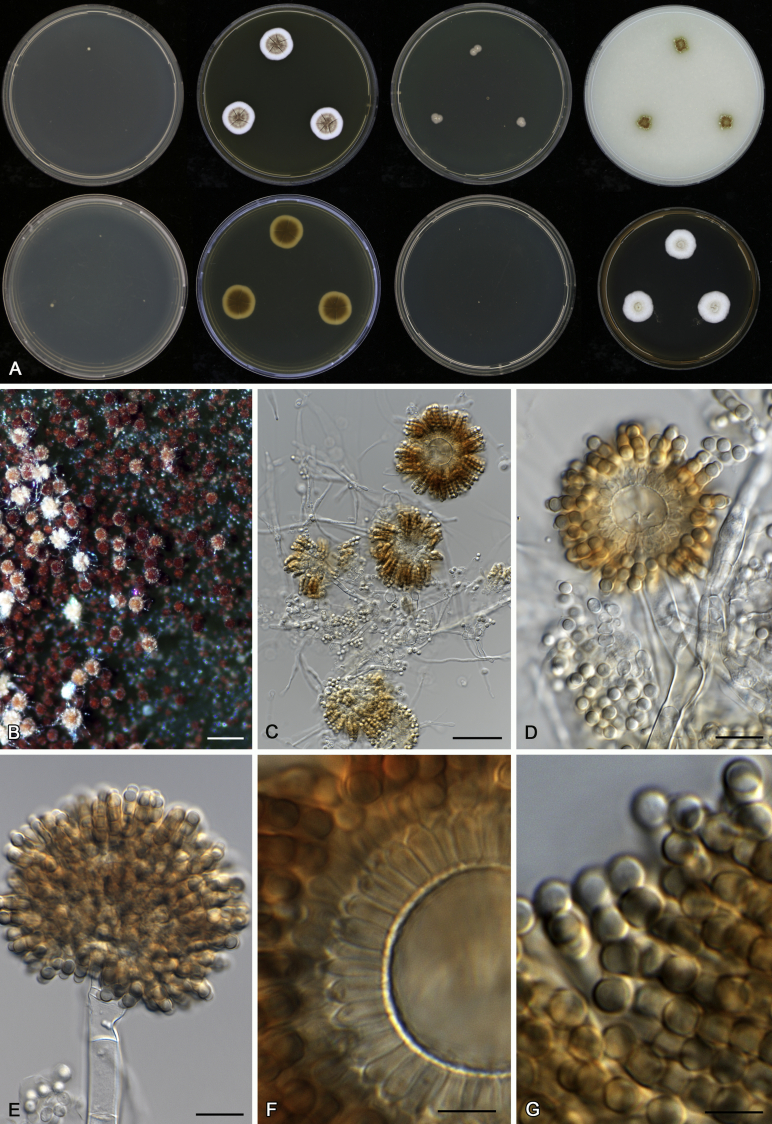

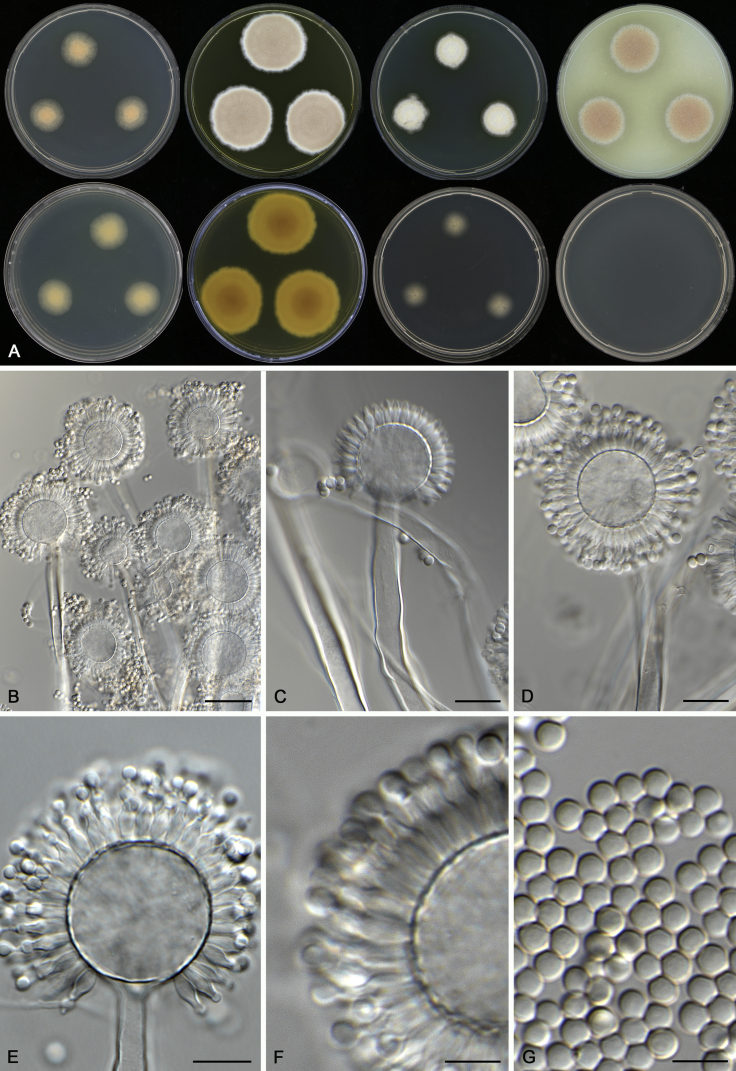

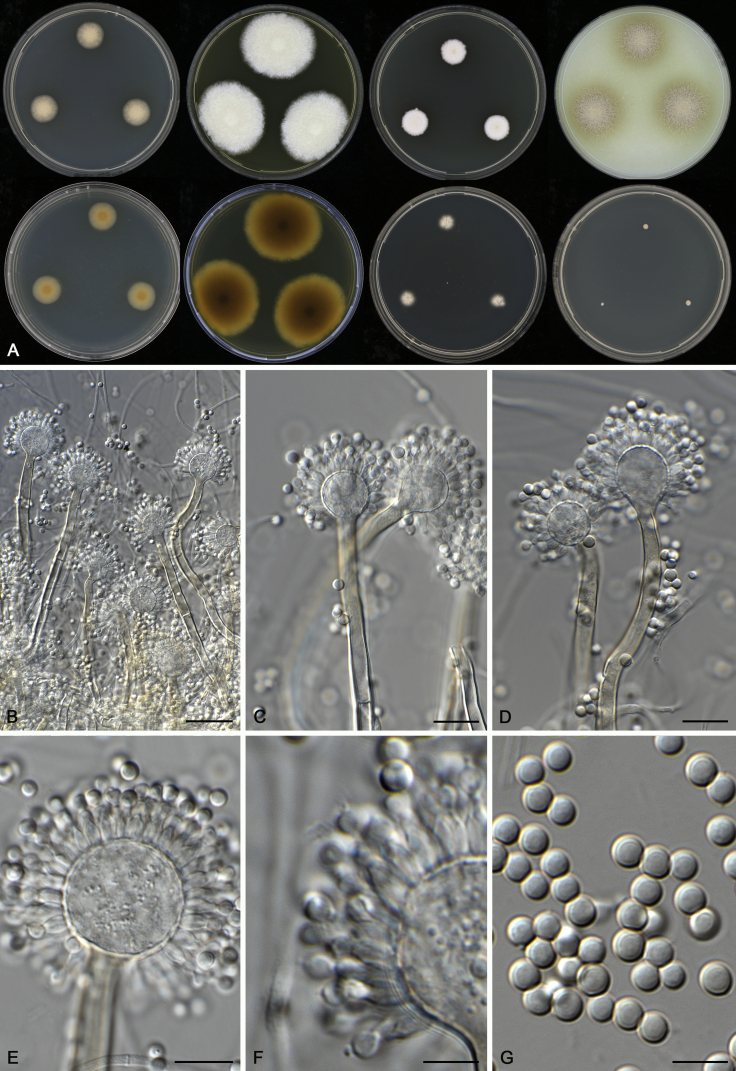

Aspergillus acidohumus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817723. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus acidohumus (CBS 141577T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CHA. B. Conidial heads on MEA after 2 wk incubation. C–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 1 000 μm; C = 30 μm; D, E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to its origin, isolated from acid soil from China.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus acidohumus grows very restrictedly on MEA, CYA, YES and OA, produces extremely compact orange brown conidial heads and tightly connected conidia, these characters can easily distinguish this species from other section Cervini members.

Typus: China, Guizhou, soil, 2014, isolated by X.Z. Jiang (holotype CBS H-22730, culture ex-type CBS 141577 = CGMCC3.18217 = DTO 340-H1 = IBT 34346).

ITS barcode: KX423646. (Alternative markers: BenA = KX423623; CaM = KX423634; RPB2 = KX423663).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA weak growth; CYA 30 °C No growth; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 18–19; MEA 30 °C 16–17; MEA 37 °C No growth; OA 6–7; YES 4–5; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 No growth; CHA 21–22.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: weak growth. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse dark fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse yellowish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation absent; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: No growth. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins irregular; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse dark fawn to brown; soluble pigments olive; exudates absent; reverse olive. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth. On CHA growth was better than on MEA but with less sporulation.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate, extremely compact; conidiophores erect, walls smooth, 40–85 (–140) × 6.5–8.5 μm; vesicles orange brown coloured, globose, 17–23 μm wide, fertile over the entire vesicles; uniseriate, phialides coloured as vesicles, flask-shaped to cylindrical, 5–6.5 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia globose, connected with each other, smooth, 3.5–4.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Aspergillus cervinus Massee, Bull. Misc. Inform. Kew 1914: 158. 1914. MycoBank MB211549. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus cervinus (CBS 537.65T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Typus: WT 540, culture ex-type: CBS 537.65 = DTO 054-D5 = ATCC 16915 = IBT 22087 = IMI 126542 = NRRL 5025 = QM 8875 = WB 5025.

ITS barcode: EF661268. (Alternative markers: BenA = EF661251; CaM = EF661261; RPB2 = EF661229).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 26–27; CYA 30 °C 25–26; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 59–60; MEA 30 °C 58–60; MEA 37 °C No growth; OA 35–40; YES 19–20; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 21–23.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse light yellow to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown to reddish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse light yellow to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to light buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse light yellow to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse cream white. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect and often terminally sinuous, walls smooth, light yellowish brown, 100–300 × 5–8 μm; vesicles hyaline to faintly coloured, globose, 15–20 μm wide, fertile over the three fourths; uniseriate, phialides hyaline, flask-shaped, 5–6.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 2.5–4 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Distinguishing characters: Phylogenetically A. cervinus clusters with A. parvulus and A. wisconsinensis in combined phylogenetic analyses, but without statistical support, it can be distinguished from A. parvulus by longer conidiophores and from A. wisconsinensis by fast growth on CYA. Morphologically, A. cervinus is similar to A. transcarpathicus, but A. transcarpathicus can grow on CYA and MEA at 37 °C.

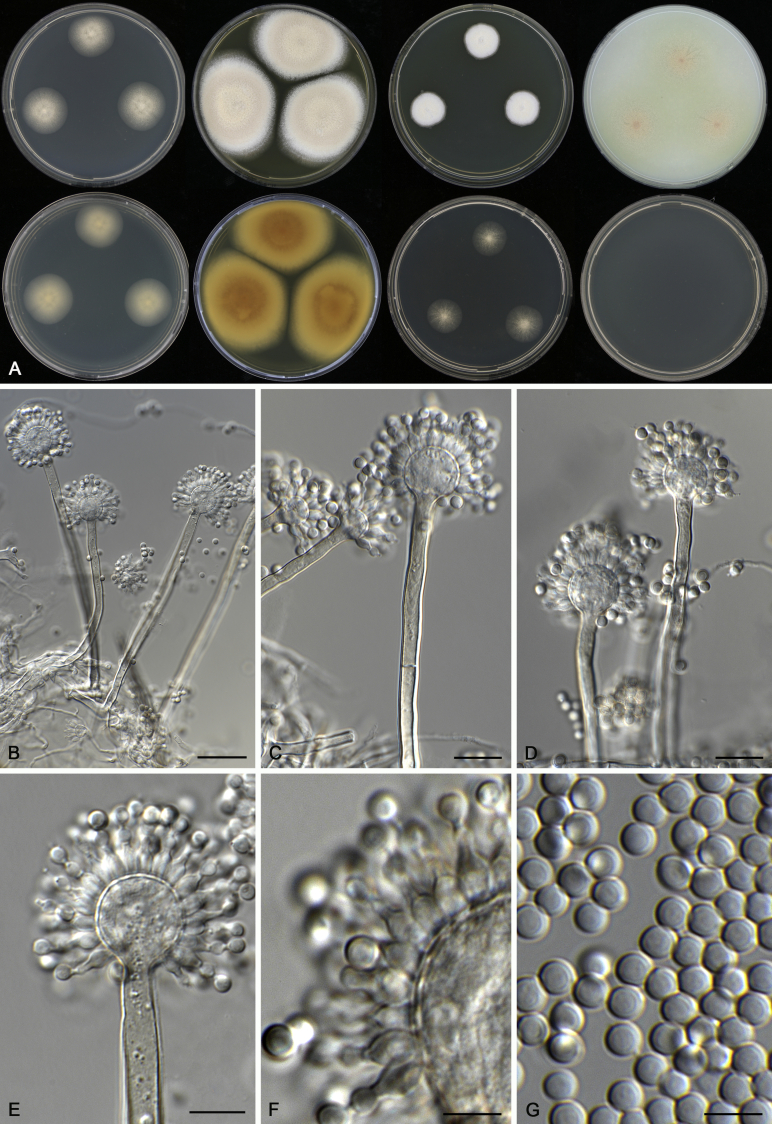

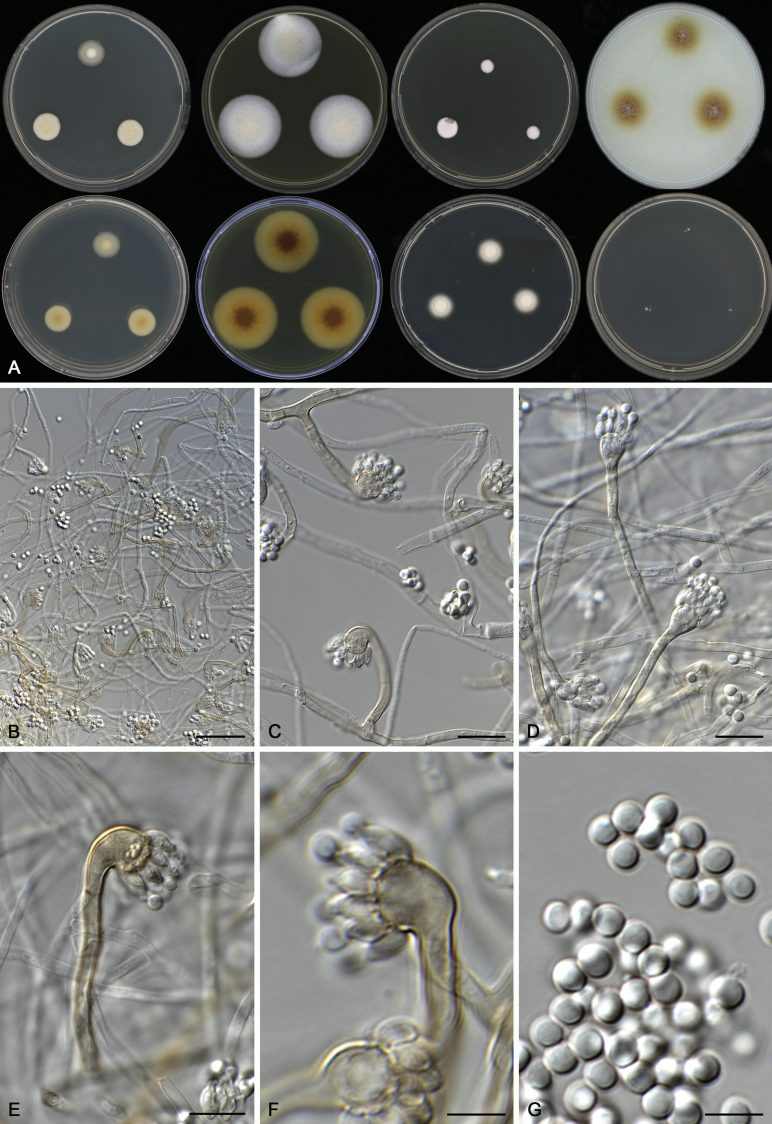

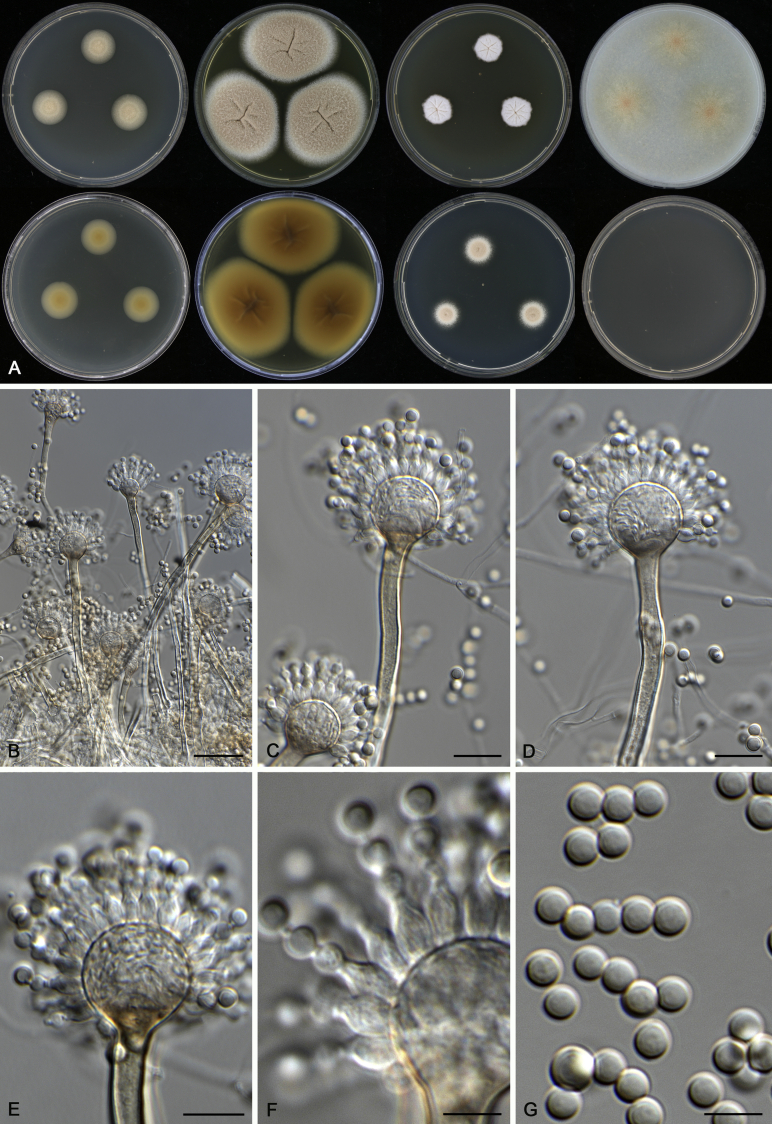

Aspergillus christenseniae A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817724. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus christenseniae (CBS 122.56T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Named in honour of Martha Christensen, who isolated the original culture.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus christenseniae is close to A. nutans and A. subnutans, but can be distinguished by its subglobose to ellipsoidal conidia.

Typus: South Africa, Pretoria, Rietvlei, soil, isolated by W.J. Lütjeharms (holotype CBS H-9217, culture ex-type: CBS 122.56 = DTO 022-C8 = IBT 22043 = IBT 23735 = IMI 343732 = NRRL 4897 = WB 4897).

ITS barcode: FJ491613. (Alternative markers: BenA = FJ491639; CaM = FJ491608; RPB2 = EF661235).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 20–29; CYA 30 °C 15–25; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 42–55; MEA 30 °C 37–52; MEA 37 °C No growth; OA 40–42; YES 9–11; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 11–15.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent to olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse cream white to yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse reddish brown at centre, yellowish brown at edge. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane to sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white to light fawn; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse yellowish brown to reddish brown. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation absent; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent to light brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse reddish brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads short columnar; conidiophores erect or bent, sometimes nodding, walls smooth, strongly yellowish brown coloured, 8–45 × 3.5–5.5 μm; vesicles coloured as the stalks, subclavate, 8–10.5 μm wide, fertile over the upper half; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 3.5–5 × 2–3.5 μm. Conidia subglobose to ellipsoidal, smooth, 4–4.5 × 3–3.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Aspergillus kanagawaensis Nehira, J. Jap. Bot. 26: 109. 1951. MycoBank MB292847. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus kanagawaensis (DTO 069-D6). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–H. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 100 μm; C, D = 30 μm; E, F = 10 μm; G, H = 5 μm.

Typus: IMI 126690, culture ex-type: CBS 538.65 = DTO 054-F3 = ATCC 16143 = IBT 22077 = IFO 6219 = IMI 126690 = NRRL 4774 = WB 4774.

ITS barcode: FJ491617. (Alternative markers: BenA = FJ491640; CaM = FJ491597; RPB2 = JN121531).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 17–20; CYA 30 °C 20–24; CYA 37 °C 10–14; MEA 45–55; MEA 30 °C 51–62; MEA 37 °C 14–25; OA 33–39; YES 15–18; CREA No growth to weak growth; CYAS 14–19; DG18 12–31.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse buff; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse cream white to yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white to light buff; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse light buff; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse buff to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to cream yellow. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent to light brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown to olive brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth to weak growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect and often terminally sinuous, smaller heads often nodding, walls smooth, light yellowish brown to light greyish, 100–800 × 5–7.5 μm; vesicles faintly coloured to light yellowish brown, globose, 20–25 μm wide, fertile over the three fourths to entire surface; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 5.5–7.5 × 3–3.5 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 2.5–3.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Distinguishing characters: Aspergillus kanagawaensis is close to A. novoguineensis, but A. novoguineensis does not grow or grows very restrictedly on CYA and MEA at 37 °C.

Notes: The ex-type culture (CBS 538.65) of A. kanagawaensis CBS 538.65 is degenerated and does not sporulate anymore; strain DTO 069-D6 was used for morphological observation and description.

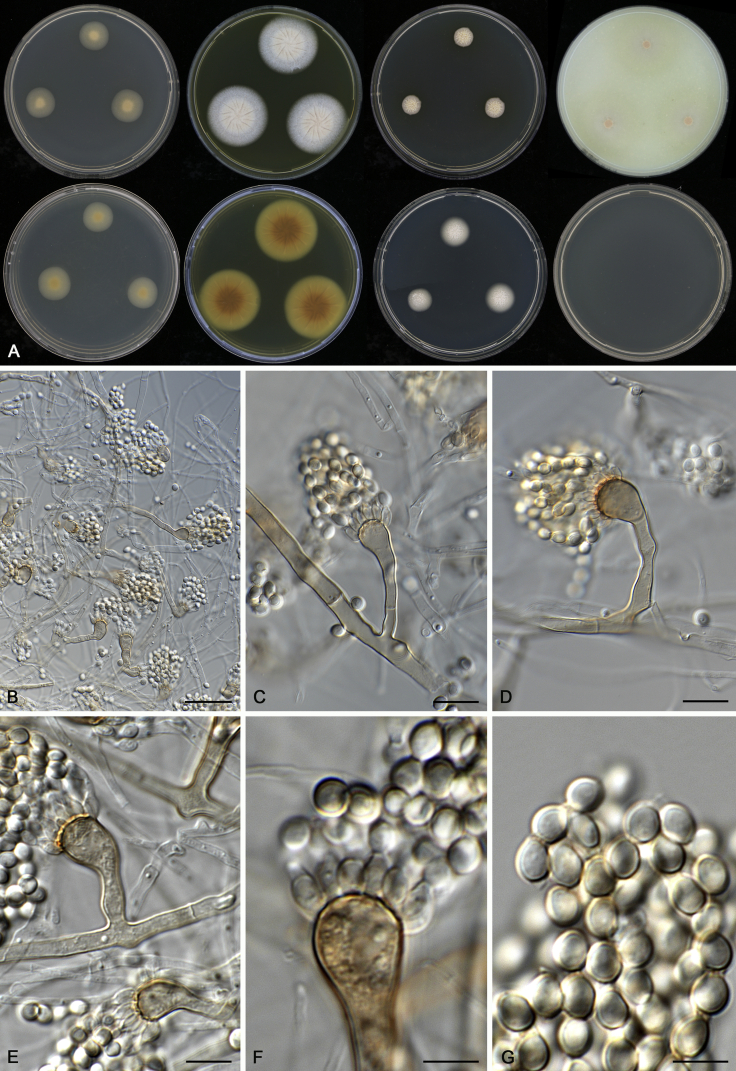

Aspergillus novoguineensis A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817725. Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus novoguineensis (CBS 906.96T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to its origin, isolated from Papua New Guinea.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus novoguineensis is closely related to A. kanagawaensis, however A. novoguineensis does not grow or grows very restrictedly at 37 °C.

Typus: Papua New Guinea, Central province, Varirata national park near Port Moresby, humus, 1995, isolated by A. Aptroot (holotype: CBS H-22729, culture ex-type: CBS 906.96 = DTO 021–G5 = IBT 29312).

ITS barcode: FJ491622. (Alternative markers: BenA = FJ491641; CaM = FJ491605; RPB2 = KX423681).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 20–21; CYA 30 °C 19–21; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 37–39; MEA 30 °C 40–43; MEA 37 °C No or weak growth; OA 29–30; YES 20–21; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 17–18.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white to light buff; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse buff; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse buff to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect, or sometimes bent, walls smooth, 210–550 × 5–7 μm; vesicles globose, 18–26 μm wide, fertile over the two thirds to entire surface; uniseriate, phialides flask-shaped, 5–8 × 2.5–3.5 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 2.5–3.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

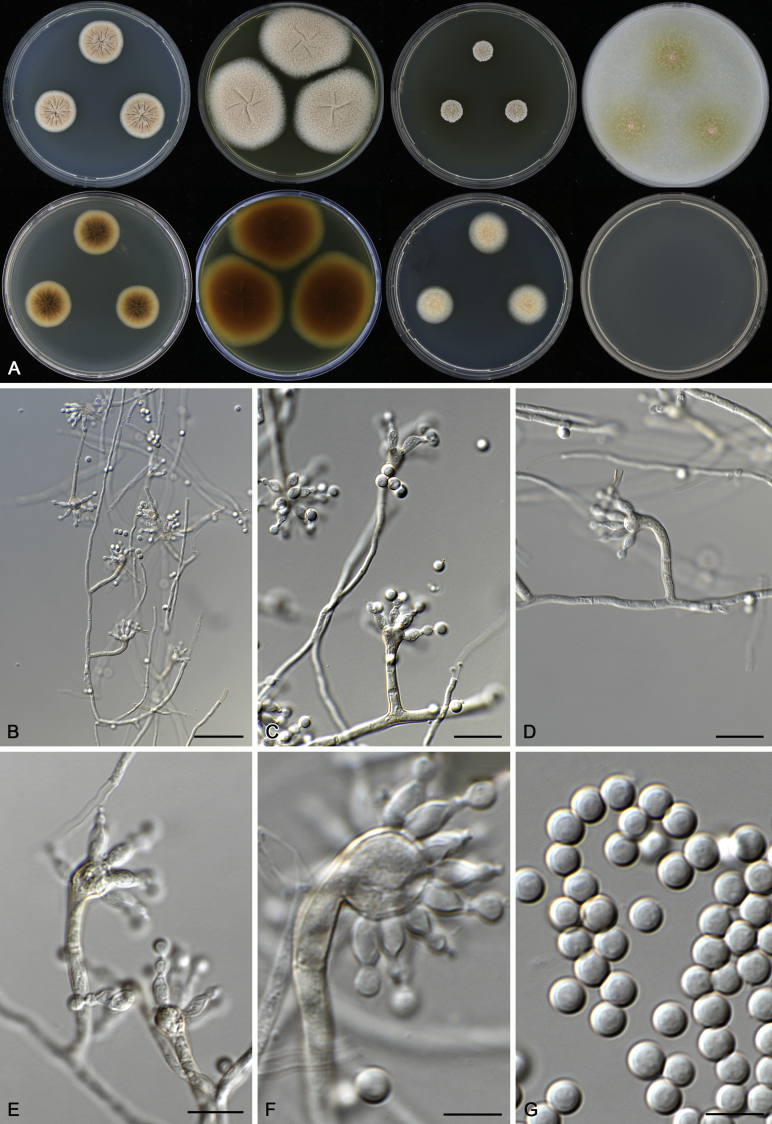

Aspergillus nutans McLennan & Ducker, Aust. J. Bot. 2: 355. 1954. Mycobank MB292850. Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus nutans (CBS 121.56T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Typus: IMI 62874ii, culture ex-type: CBS 121.56 = DTO 054-D3 = NRRL 575 = NRRL 4364 = NRRL A–6280 = ATCC 16914 = IFO 8134 = IMI 062874ii = IMI 62874 = QM 8159 = WB 4364 = WB 4546 = WB 4776.

ITS barcode: EF661272. (Alternative markers: BenA = EF661249; CaM = EF661262; RPB2 = EF661227).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 15–16; CYA 30 °C 17–19; CYA 37 °C Weak growth; MEA 38–42; MEA 30 °C 46–47; MEA 37 °C 6–8; OA 25–26; YES 9–12; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 18–19.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse buff to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, slightly sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse reddish brown at centre, yellowish brown at edge. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation moderately dense to dense, conidia en masse white to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads short columnar; conidiophores erect or bent, sometimes nodding, walls smooth, yellowish brown, 25–80 × 2–4 μm; vesicles coloured as the stalks, subclavate, sometimes borne at acute angles, 5–10 μm wide, fertile over the upper half to two thirds; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 3.5–6 × 2–3 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 2.5–3.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Distinguishing characters: Aspergillus nutans can be distinguished from other Cervini members by columnar conidial heads, strongly pigmented, short, nodding conidiophores and globose conidia.

Aspergillus parvulus G. Sm., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 44: 45. 1961. MycoBank MB121074. Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus parvulus (CBS 136.61T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Typus: IMI 86558, culture ex-type: CBS 136.61 = DTO 021-G8 = IBT 22085 = ATCC 16911 = IMI 086558 = LSHB BB405 = NRRL 1846 = NRRL 4753 = QM 7955 = UC 4613 = WB 4753.

ITS barcode: EF661269. (Alternative markers: BenA = EF661247; CaM = EF661259; RPB2 = EF661233).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 22–23; CYA 30 °C 23–24; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 35–46; MEA 30 °C 50–51; MEA 37 °C 5–6; OA 29–30; YES 10–11; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 19–22.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse reddish brown at centre, yellowish brown at edge. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse reddish brown at centre, yellowish brown at edge. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse ochraceous buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to buff. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse olive brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect or bent, sometimes nodding, walls smooth, yellowish brown, 17–75 × 2.5–3.5 μm; vesicles faintly coloured to light yellowish brown, mainly globose, sometimes subclavate, 5–11 μm wide, fertile over the two thirds to three fourths; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 4–7 × 2–3 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 2.5–4 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Distinguishing characters: The short conidiophores (< 100 μm) can distinguish Aspergillus parvulus from phylogenetically related species A. cervinus and A. transcarpathicus. Morphologically A. parvulus resembles A. nutans and A. subnutans, but the latter two produce short columnar conidial heads.

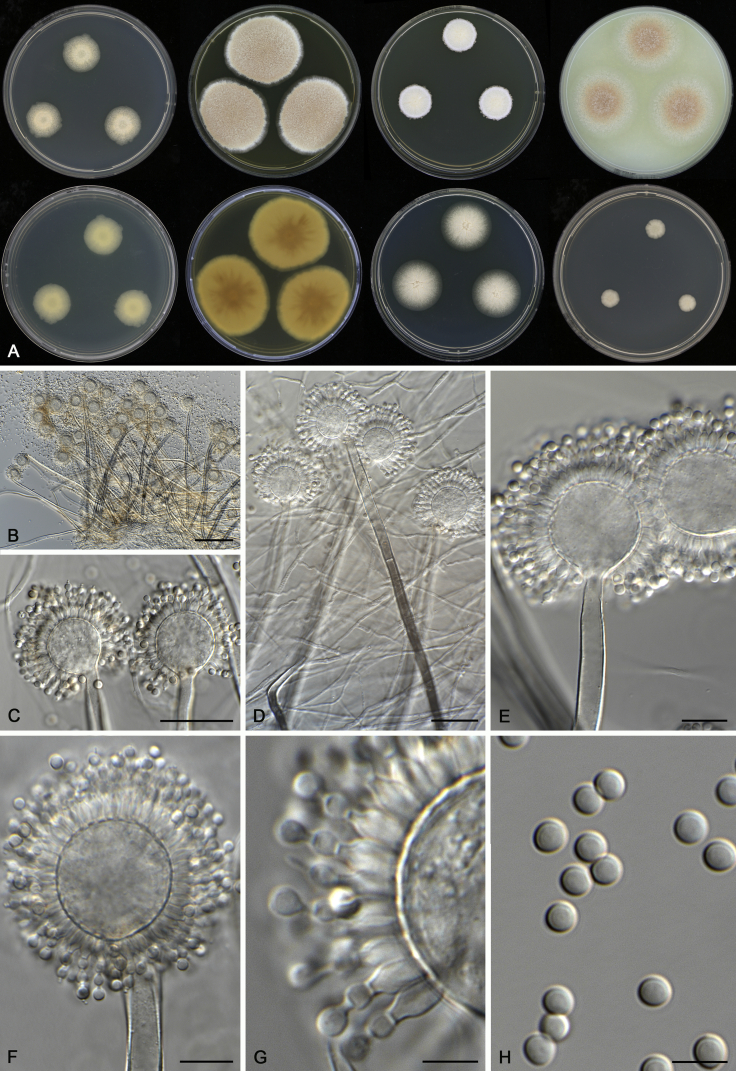

Aspergillus subnutans A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817726. Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus subnutans (CBS 129386T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to its resemblance with A. nutans.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus subnutans resembles A. nutans phylogenetically and morphologically, but differs in upright, uncoloured vesicles.

Typus: USA, Wisconsin, soil under Tsuga canadensis, 1960, isolated by M. Christensen (holotype: CBS H-22728, culture ex-type: CBS 129386 = DTO 202–C2 = WSF 445 = IBT 34352).

ITS barcode: KX528456. (Alternative markers: BenA = KX528454; CaM = KX528455; RPB2 = KX528453).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 17–18; CYA 30 °C 17–18; CYA 37 °C 4–6; MEA 34–35; MEA 30 °C 32–33; MEA 37 °C 10–11; OA 32–35; YES 15–16; CREA No growth; CYAS 7–8; DG18 14–19.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse white to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse cream white. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins irregular; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense to dense, conidia en masse white to light fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to light buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse light fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse light fawn; soluble pigments olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse olive brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads short columnar; conidiophores erect or bent, walls smooth, 25–50 × 3.5–5 μm; vesicles subclavate, 7–13 μm wide, fertile over the upper half to two thirds; uniseriate, phialides flask-shaped, 5.5–7 × 2.5–3 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 3–4 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Notes: The ex-type culture (CBS 129386 = DTO 202-C2 = WSF 445 = IBT 34352) was considered as an aberrant strain of A. nutans due to their high morphological similarity (Christensen et al. 1964). Our molecular results warrant it as a unique species.

Aspergillus transcarpathicus A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817727. Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus transcarpathicus (CBS 423.68T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to its origin, isolated from Transcarpathia, Ukraine.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus transcarpathicus resembles A. cervinus, but differs by ability of growing on CYA and MEA at 37 °C.

Typus: Ukraine, Transcarpathia, soil, deposited by L.A. Belyakova (holotype: CBS H-22727, culture ex-type: CBS 423.68 = DTO 022-C7 = IBT 22080 = IMI 134108 = VKM F-1331).

ITS barcode: FJ491624. (Alternative markers: BenA = FJ491632; CaM = FJ491610; RPB2 = KX423680).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 14–20; CYA 30 °C 11–24; CYA 37 °C 4–10; MEA 44–60; MEA 30 °C 37–60; MEA 37 °C 12–18; OA 37–43; YES 10–17; CREA No growth; CYAS No growth; DG18 8–23.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane to sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn or light yellow; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse reddish brown at centre, yellowish brown at edge. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse light yellow to fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white to light buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse cream white. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments light brown to olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse cream white to olive brown to brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect and often terminally sinuous, walls smooth, yellowish brown, 100–150 × 5.5–7.5 μm; vesicles faintly coloured, globose, 15–20 μm wide, fertile over the two thirds to entire surface; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 4.5–6.5 × 2.5–3 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 3–4 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Notes: Hubka et al. (2012) reported a isolation of section Cervini member from suspected onychomycosis. Their isolate CCF 3945 shows 94.2 % and 96.6 % similarity with A. parvulus in BenA and CaM sequences respectively. This isolate is identified as A. transcarpathicus here according to sequence data (BenA = FR775332, CaM = FR837972, RPB2 = FR837980).

Aspergillus vinosobubalinus Udagawa, Kamiya & Kaori Osada, Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan 34: 255. 1993. MycoBank MB361186.

Typus: CBM BF-33501. Culture ex-type: CBM BF-33501.

ITS barcode: n.a. (Alternative markers: BenA = n.a.; CaM = n.a.; RPB2 = n.a.).

Colony characters: Fide Udagawa et al. (1993) Colonies on Czapek agar growing rapidly, attaining a diameter of 40–44 mm in diam within 7 days at 25 °C, velvety, loose-textured, more or less zonate, consisting of a thin basal felt from which conidiophores moderately arise, Purplish Gray (M. 13D2 after Kornerup & Wanscher 1978) or Fawn (Rayner 1970), becoming Brownish Gray (M. 8D2) or Vinaceous Buff (Rayner) in age; reverse uncoloured. Colonies on CYA spreading broadly, attaining a diameter of 85 mm within 7 days at 25 °C, velvety, zonate, furrowed in a radial pattern, consisting of a rather compact basal felt, usually producing abundant conidial heads, sometimes intermixed with Orange (M. 5A5) or saffron (Rayner) sclerotia on the felt, Purplish Gray (M. 14B2), becoming Brownish Gray (M. 8C2) or Vinaceous Buff (Rayner) in age; sclerotia produced more abundantly in granular appearance in the dark-incubated cultures; exudate lacking; reverse Pale Yellow (M. 4A3) or Buff (Rayner). Colonies on CYA with 20 % sucrose (CYA20S) spreading broadly, growth rate and other characters similar to those on CYA. Colonies on malt extract agar (MEA) growing rapidly, attaining a diameter of 63–64 mm within 7 days at 25 °C, velvety, plane, consisting of a thin submerged mycelium from which numerous conidiophores arise, Reddish Lilac (M. 14C3) to Dull Lilac (M. 15C3); exudate lacking; reverse uncoloured to Yellowish Gray (M. 4B2) or Smoke Gray (Rayner).

Micromorphology: Fide Udagawa et al. (1993) Conidial heads radiate, splitting into columns in age, 250–350 μm in diam. Conidiophores straight to terminally sinuous, sometimes nodding; stipes 550–1 200 × 10–12.5 μm, with walls smooth and thickened up to 2 μm near the base, upper portion light yellowish brown; vesicles globose to more or less elongate, 30–45 μm in diam, brownish, fertile over the entire surface. Aspergilla uniseriate with tightly packed phialides; phialides cylindric, 5–7.5 (–10) × 2.5–3 (−5) μm. Conidia hyaline, pale yellowish brown in mass, globose to subglobose, 3–4.5 × 3–4 μm, at first echinulate and thin-walled, becoming verruculose with small warts, diminutive aspergilla sometimes present; conidiophores 150–350 × 3.5–5 μm; vesicles flask-shaped, 7.5–15 μm in diam, fertile over upper half to two-thirds; phialides 7.5–10 × 2.5–3 μm; conidia as described. Sclerotia greyish orange or saffron, mostly subglobose, sometimes elongate, 380–600 μm in diam, composed of angular, thick-walled, 15–30 × 10–24 μm cells; no evidence of asci through three months on CYA, CYA20S or MEA.

Distinguishing characters: The rapid growth on CYA (85 mm within 7 d), saffron-coloured sclerotia and wide vesicles (30–45 μm) can easily distinguish A. vinosobubalinus from other section Cervini members.

Notes: According to the original description, A. vinosobubalinus is characterised by fawn, radiate conidial heads, uniseriate, globose to elongate vesicles, which fit the morphological features of section Cervini (Udagawa et al. 1993). Unfortunately, the ex-type culture and sequence data of A. vinosobubalinus were not available for this study.

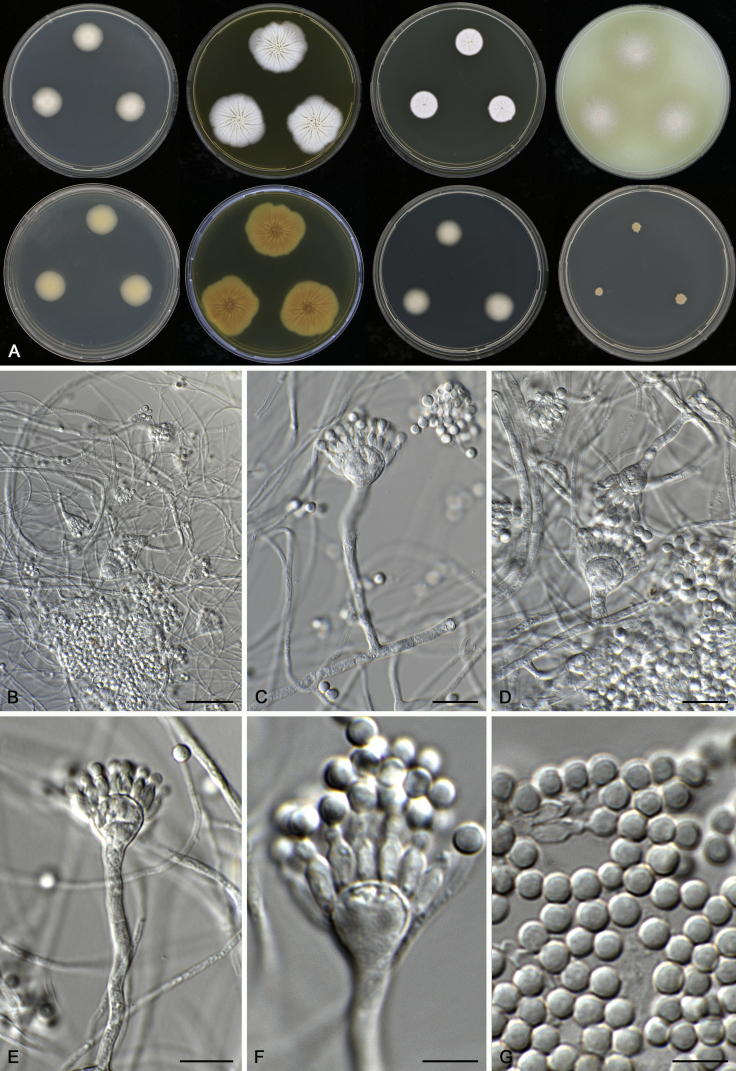

Aspergillus wisconsinensis A.J. Chen, Frisvad & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB817728. Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Morphological characters of Aspergillus wisconsinensis (CBS 413.64T). A. Colonies: top row left to right, CYA, MEA, YES and OA; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, reverse MEA, DG18 and CYA 37 °C. B–G. Conidiophores and conidia. Scale bars: B = 30 μm; C–E = 10 μm; F, G = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to its origin, isolated from soil under Tsuga canadensis, USA, Wisconsin.

Diagnosis: Aspergillus wisconsinensis resembles A. cervinus and A. transcarpathicus. It differs from A. cervinus by slow growth on CYA and from A. transcarpathicus by its lack of growth at 37 °C.

Typus: USA, Wisconsin, near Madison, soil under Tsuga Canadensis, isolated by M. Christensen (holotype: CBS H-9203, culture ex-type: CBS 413.64 = DTO 022–B1 = NRRL 5027 = IBT 22042 = IBT 22082 = WSF 380 = DTO 070-A5 = WB 5027).

ITS barcode: FJ491618. (Alternative markers: BenA = FJ491638; CaM = FJ491609; RPB2 = KX423671).

Colony diam, 7 d (mm): CYA 13–17; CYA 11–16; CYA 37 °C No growth; MEA 51–53; MEA 30 °C 40–43; MEA 37 °C No growth; OA 25 °C 35–40; YES 14–23; CREA No growth; CYAS Weak growth; DG18 14–19.

Colony characters: CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse yellowish brown. MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear droplets; reverse yellowish brown. YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, sulcate; margins entire; mycelium white; texture floccose; sporulation dense, conidia en masse white to light fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse ochraceous buff. DG18 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies moderately deep, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse yellowish brown at centre, cream white at edge. OA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies low, plane; margins entire; mycelium white; texture velvety; sporulation moderately dense, conidia en masse fawn; soluble pigments olive brown; exudates clear droplets; reverse brown. CREA 25 °C, 7 d: No growth.

Micromorphology: Conidial heads radiate; conidiophores erect or bent, yellowish brown, 100–200 × 4–7 μm; vesicles coloured as the stalks, subclavate to globose, 14–20 μm wide, fertile over the two thirds; uniseriate, phialides faintly coloured, flask-shaped, 5–7 × 2.5–3.5 μm. Conidia globose, smooth, 3–4.5 μm. Ascomata not produced.

Dichotomous key to species from section Cervini

| 1a) | Conidial heads short columnar ……………………………………………. 2 |

| 1b) | Conidial heads radiate ……………………………………………………… 4 |

| 2a) | Conidia subglobose to ellipsoidal ……………………… A. christenseniae |

| 2b) | Conidia globose ……………………………………………………………... 3 |

| 3a) | Vesicles strongly pigmented, nodding ………………………….. A. nutans |

| 3b) | Vesicles upright, uncoloured ………………………………… A. subnutans |

| 4a) | Conidiophores mainly not exceeding 100 μm in length ………………... 5 |

| 4b) | Conidiophores exceeding 100 μm in length ……………………………... 6 |

| 5a) | Vesicles exceeding 15 μm in width ………………………. A. acidohumus |

| 5b) | Vesicles not exceeding 15 μm in width ……………………… A. parvulus |

| 6a) | Conidiophores usually 100–300 μm in length …………………………... 7 |

| 6b) | Conidiophores extremely variable, 1 001 200 μm in length ……………. 9 |

| 7a) | Grow on CYA and MEA at 37 °C .………………….. A. transcarpathicus |

| 7b) | Does not grow on CYA and MEA at 37 °C ……………………………... 8 |

| 8a) | Slow growth (<20 mm, 25 °C, 7d) on CYA …………. A. wisconsinensis |

| 8b) | Fast growth (>25 mm, 25 °C, 7d) on CYA ………………….. A. cervinus |

| 9a) | Fast growth (>80 mm, 25 °C, 7d) on CYA ………… A. vinosobubalinus |

| 9b) | Slow growth (<40 mm, 25 °C, 7d) on CYA …………………………… 10 |

| 10a) | No growth or restricted growth on CYA and MEA at 37 °C ……………………………………... A. novoguineensis |

| 10b) | Grows on CYA and MEA at 37 °C …………………... A. kanagawaensis |

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to the late Dr János Varga, who started this work and published many papers on the taxonomy of the genus Aspergillus. This research was supported by the Hungarian Research Fund (OTKA K115690).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre.

Contributor Information

A.J. Chen, Email: amanda_j_chen@163.com.

R.A. Samson, Email: r.samson@cbs.knaw.nl.

References

- Bartman C.D., Campbell I.M. Naphthalenone production in Aspergillus parvulus. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1979;25:130–137. doi: 10.1139/m79-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bös M., Canesso R., Inoue-Ohga N. O-methylasparvenone, a nitrogen-free serotonin antagonist. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 1997;5:2165–2171. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buiak L.I., Al-Nuri M.A., Landau N.S. Effect of a stimulating factor formed by Aspergillus wentii on exoprotease biosynthesis by a culture of Aspergillus kanagawaensis. Mikrobiologiia. 1978;47:1004–1009. [Article in Russian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao P.D., Schiff P.L., Jr., Slatkin D.J. Metabolites of aspergilli. II. Asparvenone and O-methylasparvenone, naphthalenones from Aspergillus parvulus. Lloydia Journal of Natural Products. 1975;38:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao P.D., Schiff P.L., Jr., Slatkin D.J. Metabolites of aspergilli. 4. Isolation and characterization of 3 new naphtalenone and one naphthaquinone metabolites of Aspergillus parvulus. Lloydia Journal of Natural Products. 1976;39:476. [Google Scholar]

- Chao P.D., Schiff P.L., Jr., Slatkin D.J. Metabolites of aspergilli. 4. New naphthalenones and 6-ethyl -7-methoxyjuglone from Aspergillus parvulus. Journal of Chemical Research. 1979;1979:236. [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.J., Frisvad J.C., Sun B.D. Aspergillus section Nidulantes (formerly Emericella): Polyphasic taxonomy, chemistry and biology. Studies in Mycology. 2016;84:1–118. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M., Fennell D.I. The rediscovery of Aspergillus cervinus. Mycologia. 1964;56:350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M., Fennell D.I., Backus M.P. Aspergillus kanagawaensis and related species in Wisconsin forest soils. Mycologia. 1964;56:354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Crous P.W., Verkley G.J.M., Groenewald J.Z. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre; Utrecht, The Netherlands: 2009. Fungal biodiversity. [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes A.M., da Costa G.L., Barcellos M.Z. The entomopathogenic potential of Aspergillus spp. in mosquitoes vectors of tropical diseases. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 2001;41:45–49. doi: 10.1002/1521-4028(200103)41:1<45::AID-JOBM45>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Menna M.E., Sayer S.T., Barratt B.I.P. Biodiversity of indigenous tussock grassland sites in Otago, Canterbury and the central North Island. V. Penicillia and aspergilli. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 2007;37:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Elsohly H.N., Slatkin D.J., Schiff P.L., Jr. Metabolites of Aspergillus cervinus Massee (Moniliaceae) Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 1974;63:1632–1633. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600631034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Frank J.M., Houbraken J. New ochratoxin producing species of Aspergillus section. Circumdati. Studies in Mycology. 2004;50:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Larsen T.O. Chemodiversity in the genus Aspergillus. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2015;99:7859–7877. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Larsen T.O. Extrolites of Aspergillus fumigatus and other pathogenic species in Aspergillus section Fumigati. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;6 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Larsen T.O., Thrane U. Fumonisin and ochratoxin production in industrial Aspergillus niger strains. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Rank C., Nielsen K.F. Metabolomics of Aspergillus fumigatus. Medical Mycology. 2009;47:S53–S71. doi: 10.1080/13693780802307720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Thrane U. Standardized high performance liquid chromatography of 182 mycotoxins and other fungal metabolites based on alkylphenone retention indices and UV-VIS spectra (diode array detection) Journal of Chromatography A. 1987;404:195–214. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)86850-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J.C., Thrane U. Liquid column chromatography of mycotoxins. In: Betina V., editor. Chromatography of mycotoxins: techniques and applications. Vol. 54. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1993. pp. 253–372. (Journal of Chromatography Library). [Google Scholar]

- Gams W., Christensen M., Onions A.H.S. Infrageneric taxa of Aspergillus. In: Samson R.A., Pitt J.I., editors. Advances in Penicillium and Aspergillus systematics. Vol. 102. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. pp. 55–62. (NATO ASI Series. Ser. A.: Life Sciences). [Google Scholar]

- Guo C.J., Sun W.W., Bruno K.S. Molecular genetic characterization of terreic acid pathway in Aspergillus terreus. Organic Letters. 2014;16:5250–5253. doi: 10.1021/ol502242a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Wijeratne E.M., Bashyal B.P. Cytotoxic and other metabolites of Aspergillus inhabiting the rhizosphere of Sonoran desert plants. Journal of Natural Products. 2004;67:1985–1991. doi: 10.1021/np040139d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houbraken J., Samson R.A. Phylogeny of Penicillium and the segregation of Trichocomaceae into three families. Studies in Mycology. 2011;70:1–51. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.70.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubka V., Kubatova A., Mallatova N. Rare and new etiological agents revealed among 178 clinical Aspergillus strains obtained from Czech patients and characterised by molecular sequencing. Medical Mycology. 2012;50:601–610. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.667578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi B.K., Gloer J.B., Wicklow D.T. Sclerotigenin: a new antiinsectan benzodiazepine from the sclerotia of Penicillium sclerotigenum. Journal of natural Products. 1999;62:650–652. doi: 10.1021/np980511n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup A., Wanscher J.H. 3rd edn. Eyre Methuen; London: 1978. Methuen handbook of colour. [Google Scholar]

- Kwasna H. Fungi in the rhizosphere of common oak and its stumps and their possible effect on infection by Armillaria. Applied Soil Ecology. 2001;17:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung K.J., Fennell D.I. A new pathogenic species of Aspergillus. Mycologia. 1971;63:478–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau N.S., Egorov N.S., Buiak L.I. Role of an exoprotease biosynthesis-stimulating microbial factor in Aspergillus kanagawaensis in the process of its growth and development. Mikrobiologiia. 1980;49:919–923. [Article in Russian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen T.O., Frydenvang K., Frisvad J.C. UV guided isolation of benzodiazepines in Penicillium. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2000;28:881–886. doi: 10.1016/s0305-1978(99)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen T.O., Smedsgaard J., Nielsen K.F. Production of mycotoxins by Aspergillus lentulus and other medically important and closely related species in section Fumigati. Medical Mycology. 2007;45:225–232. doi: 10.1080/13693780601185939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K.H., Liou H.H., Yang C.M. Isolation, chemical structure, acute toxicity, and some physicochemical properties of territrem C from Aspergillus terreus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1984;47:98–100. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.1.98-100.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnoli C., Dalcero A.M., Chiacchiera S.M. Enumeration and identification of Aspergillus group and Penicillium species in poultry feeds from Argentina. Mycopathologia. 1998;142:27–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1006981523027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massee G.E. Fungi Exotici XVIII. Aspergillus cervinus Massee. Kew Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew) 1914;1914:158. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan E.I., Ducker S.C., Thrower L.B. New soil fungi from Australian heathland: Aspergillus, Penicillium and Spegazzinia. Australian Journal of Botany. 1954;2:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Nehira T. A new species of the genus Aspergillus isolated in Japan. Journal of Japanese Botany. 1951;26:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Neill J.C. The mould fungi of New Zealand. Royal Society of New Zealand Transactions & Proceedings. 1939;69:237–264. [Google Scholar]

- Nong X.H., Wang Y.F., Zhang X.Y. Territrem and butyrolactone derivatives from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:6113–6124. doi: 10.3390/md12126113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S.W. Phylogenetic relationships in Aspergillus based on rDNA sequence analysis. In: Samson R.A., Pitt J.I., editors. Integration of modern taxonomic methods for Penicillium and Aspergillus classification. Harwood Academic Publishers; Amsterdam: 2000. pp. 323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S.W. Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus species using DNA sequences from four loci. Mycologia. 2008;100:205–226. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.100.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S.W., Varga J., Frisvad J.C. Phylogeny and subgeneric taxonomy of Aspergillus. In: Varga J., Samson R.A., editors. Aspergillus in the genomic era. Wageningen Academic Publishers; Wageningen: 2008. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Phoebe C.H., Slatkin D.J., Schiff P.L. Metabolites of Aspergilli. 5. Terremutin and terremutin hydrate, an artefact, from Aspergillus nutans. Lloydia Journal of Natural Products. 1978;41 662–662. [Google Scholar]

- Poch G.K., Gloer J.B., Shearer C.A. New bioactive metabolites from a freshwater isolate of the fungus Kirsteiniothelia sp. Journal of Natural Products. 1992;55:1093–1099. doi: 10.1021/np50086a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D., Crandall K.A. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper K.B., Fennell D.I. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1965. The genus Aspergillus. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes version 3.0: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner R.W. Commonwealth Mycological Institute; Great Britain: 1970. A mycological colour chart. [Google Scholar]

- Samson R.A. A compilation of the Aspergilli described since 1965. Studies in Mycology. 1979;18:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Samson R.A., Houbraken J., Frisvad J.C. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre; Utrecht: 2010. Food and indoor fungi. [Google Scholar]

- Samson R.A., Visagie C.M., Houbraken J. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Studies in Mycology. 2014;78:141–173. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Lambu M.R., Jamwal U. Escherichia coli N-acetylglucosamine-I-phosphate uridyltransferase/glucosamine-I-phosphate-acetyltransferase (GlmU) inhibitory activity of terreic acid isolated from Aspergillus terreus. Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 2016;21:342–353. doi: 10.1177/1087057115625308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedsgaard J. Micro-scale extraction procedure for standardized screening of fungal metabolite production in cultures. Journal of Chromatography A. 1997;760:264–270. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. Some new and interesting species of micro-fungi. British Mycological Society Transactions. 1961;44:12–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web-Servers. Systematic Biology. 2008;75:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsyganenko K.S., Zaichenko O.M. Antibiotic and phytotoxic properties of some Aspergillus parvulus Smith strains. Mikrobiolohichnyĭ Zhurnal. 2004;66:62–67. [Article in Ukrainian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsyganenko K.S., Zaichenko O.M. Antibiotic properties of some species of genus Aspergillus MICH. Mikrobiolohichnyĭ Zhurnal. 2004;66:56–61. [Article in Ukrainian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa S., Kamiya S., Osada K. Aspergillus vinosobubalinus, a new species in Aspergillus section Cervini. Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan. 1993;34:255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ushakova V.I., Dalko L.D., Egorov N.S. Study of the protease complex synthetized by Aspergillus kanagawaensis in relation to its fibrinolytic activity. Nauchnye Doklady Vyssheĭ Shkoly. Biologicheskie Nauki. 1974;1974:93–97. [Article in Russian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga J., Frisvad J.C., Samson R.A. Two new aflatoxin producing species, and an overview of Aspergillus section Flavi. Studies in Mycology. 2011;69:57–80. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.69.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visagie C.M., Varga J., Houbraken J. Ochratoxin production and taxonomy of the yellow aspergilli (Aspergillus section Circumdati) Studies in Mycology. 2014;78:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicklow D.T., Whittingham W.F. Soil microfungal changes among the profiles of disturbed conifer-hardwood forests. Ecology. 1974;55:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.H., Lu C.H., Zheng Z.H. New polyketides isolated from Botrysphaeria australis strain ZJ12-1A. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2011;94:897–902. [Google Scholar]