Abstract

A small proportion of cancer cells have stem-cell-like properties, are resistant to standard therapy and are associated with a poor prognosis. The metabolism of such drug-resistant cells differs from that of nearby non-resistant cells. In this study, the metabolism of drug-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells was investigated. The expression of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondrial membrane was negatively correlated with the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Because the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) reflects the functional status of mitochondria and metastasis is the principal cause of death due to cancer, the relationship between MMP and metastasis was evaluated. Cells with a higher MMP exhibited greater migration and invasion than those with a lower MMP. Cells that survived treatment with cisplatin, a standard chemotherapeutic drug for lung adenocarcinoma, exhibited increased MMP and enhanced migration and invasion compared with parental cells. Consistent with these findings, inhibition of mitochondrial activity significantly impeded the migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells. RNA-sequencing analysis indicated that the expression of mitochondrial complex genes was upregulated in cisplatin-resistant cells. These results suggested that drug-resistant cells have a greater MMP and that inhibition of mitochondrial activity could be used to prevent metastasis of drug-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Introduction

Lung cancer accounted for 22.8% of all deaths due to cancer in Korea in 2013.1 Approximately 85–90% of all cases of lung cancer are characterized as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for which platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment.2 Among NSCLCs, adenocarcinoma is the most common type in Korea.3 Despite advances in cancer treatment, treatment fails in many cases, resulting in disease progression, recurrence and metastasis.4 One of the major reasons for treatment failure is intratumoural heterogeneity; a small number of cells have stem-cell-like properties (or stemness), and can survive treatment with common anticancer drugs.4, 5 Cancer cells with stemness are also the principal population that undergoes metastasis.6, 7, 8

Reprogramming of energy metabolism is one of the hallmarks of cancer9 and a target for anticancer drug development.10 Much evidence suggests that the metabolism of tumor cells is heterogeneous.11 In particular, cancer cells with stemness have a metabolism distinct from that of nearby non-stemness cells.11 For example, cancer cells generally rely on glycolysis to support their rapid proliferation; however, in ovarian,12 breast13 and colon14 cancer, proliferation of cells with stemness is dependent on mitochondrial energy production.

To reduce the number of deaths due to cancer, it is important to eradicate or prevent metastasis by cancer cells with stemness. Because stemness populations must survive standard treatments before undergoing metastasis, controlling the drug-resistant cancer cell population is vital. This could be achieved by exploiting the difference in metabolism between the overall cancer cell population and those resistant to therapeutics. Therefore, the difference in metabolism between the overall cancer cell population and the drug-resistant population was investigated in this study. The results revealed that the drug-resistant population of NSCLC adenocarcinoma cells exhibited a higher mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and enhanced migration and invasion compared with the parental cell population. Moreover, inhibition of mitochondrial activity hampered the migration and invasion of the drug-resistant cell population. These findings suggested that treatment with mitochondria inhibitors could reduce the incidence of metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma following platinum-based therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and chemicals

Human non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) adenocarcinoma cell lines, A549 and H1650, were purchased from Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Korea) and cultured in RPMI (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified incubators.

Rotenone (#R8875), cisplatin (#c2210000), SRB (Sulforhodamine B; #S1402) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro- 1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl benzimidazolyl carbocyanine iodide; M34152) was from Molecular Probe (Eugene, OR, USA), TMRE (Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester; ab113852) was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), MitoTrackerGreen FM (#9074) was from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), 7-AAD (7-amino actinomycin D; #559925) was from BD BioSciences (San Jose, CA, USA), DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, #268298) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA), and PrestoBlue cell viability reagent (#A13262) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Flow cytometry analysis was done as reported previously15 at Flow Cytometry Core (National Cancer Center). MMP and contents were analyzed by flow cytometry using JC-1, TMRE and MitoTracker as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were dissociated to single cells using trypsin/EDTA and incubated with JC-1 (2 μM) alone or both TMRE (100 nM) and 7-AAD (2.5 μg ml−1) or MitoTracker (400 nM) alone, then analyzed by FACSVerse flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). For cell sorting, dissociated single cells were stained with JC-1 and cells with upper and lower 20% of MMP were sorted using FACSort flow cytometry (BD Biosciences).

Migration and invasion assay

Boyden chamber migration and invasion assay were done as reported previously.16

Adenosine triphosphate measurement

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells per well), cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) level was measured using a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (#G7572, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions as reported previously.17

Cell proliferation and viability assay

Proliferation rate was determined by SRB colorimetric assay as reported.18 Briefly, cells were fixed with 50% trichloroacetic acid and dried, then stained with 0.4% SRB solution. The protein-bound dye was dissolved by 10 mM Tris base solution and the optical density was determined at 515 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Cell viability was quantified by PrestoBlue cell viability reagent (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA from A549 and A549R cells were extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instruction. Preparation of RNA library and sequencing were performed by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea). RNA library was prepared using TruSeq RNA kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequencing was done using HiSeq 2000 sequencing system (Illumina).

Real-time imaging of mitochondrial membrane potential

Both green and red fluorescent image and bright field image of A549 cells treated with JC-1 (2 μM) were acquired in an IncuCyte ZOOM live-cell imaging system (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) with a × 10 objective for 24 h in every 2 h interval.

Image-based quantification of cell number

Cells were incubated with DAPI (2 μg ml−1) for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed using the Cytation-3 cell imaging multi-mode microplate reader with a × 4 objective (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Mitochondrial complex 1 enzyme activity

Complex 1 activity was quantified by a complex 1 enzyme activity dipstick assay kit (ab109720, Abcam) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, lysates from 1 × 105–4 × 106 of A549 and A549R cells were allowed to wick up into the dipstick, which immunocaptured complex 1. The dipstick was immersed in complex 1 activity buffer solution containing NADH as a substrate and nitrotetrazolium blue as the electron acceptor. Reduced nitrotetrazolium blue formed a blue–purple precipitate at the complex 1 antibody line on the dipstick, whose signal intensity was corresponded to the level of complex 1 activity.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was done as reported.19 Briefly, data were presented as means±s.d., and P-values were calculated using the Student's t-test calculator. All data were representative of at least three separate experiments.

Results

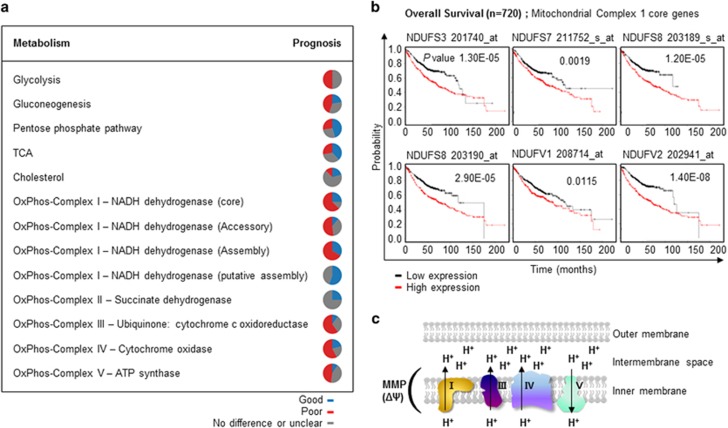

Expression of mitochondrial membrane genes is negatively correlated with the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma

The relationship between the expression of energy metabolism-related genes and prognosis was evaluated using a Kaplan–Meier survival plot generated by a meta-analysis of published lung cancer microarray data sets20 (Supplementary Table 1). In total, 866 lung adenocarcinoma patients were categorized according to the median expression level of specific genes, and the difference in overall survival was investigated. Genes with a P-value <0.05 were considered to be significantly associated with prognosis. If one gene has multiple probes (Affymetrix identification; Affid) showing different prognosis, that gene was regarded as ‘no difference or unclear'. The percentage of genes in each metabolic pathway subset associated with prognosis was evaluated and is presented as a circular diagram. The results suggested that the majority of metabolism-related genes was correlated with prognosis (Figure 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Consistent with previous reports that many glycolytic genes are upregulated in cancer cells and are candidate targets for the development of anticancer drugs,21, 22 ~50% of glycolysis-related genes were negatively correlated with prognosis. Interestingly, the majority of genes whose products mediate oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) in the mitochondrial membrane were negatively correlated with prognosis (Figures 1a and b). These genes, the products of which comprise mitochondrial OxPhos complexes I, III and IV, create the MMP by generating a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (Figure 1c). Thus, it was hypothesized that the MMP is associated with the prognosis of lung cancer.

Figure 1.

The expression of energy metabolism-related genes is negatively correlated with the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. (a) Correlations between the expression of energy metabolism-related genes and prognosis were analyzed using an open database20 with the data of 866 lung adenocarcinoma patients. The percentage of genes associated with a particular prognosis in each metabolic pathway subset is shown. Blue, positive prognosis; red, negative prognosis; gray, no difference in prognosis or unclear. (b) Mitochondrial complex 1 genes and their associations with overall survival. A list of all genes in specific metabolic pathways and their correlations with prognosis is shown in Supplementary Table 1. (c) Schematic diagram of the associations of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) complex genes with MMP.

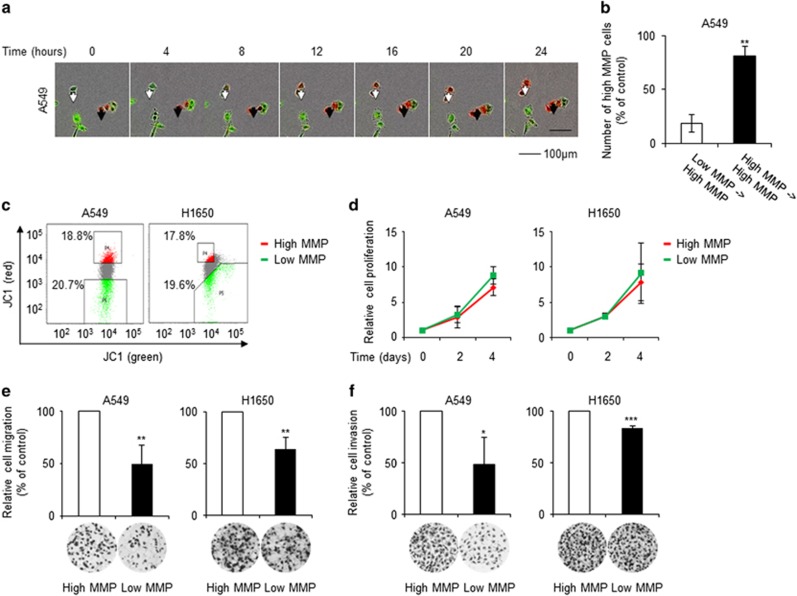

High-MMP cells exhibit increased migration and invasion

Because the major cause of death due to cancer is metastasis,23 the prognosis is closely correlated with the rate of metastasis. Thus, the relationship between MMP and metastasis was investigated in this study. MMP, which reflects the functional status of mitochondria, differs among individual cells under normal growth conditions.24 First, the heterogeneity of the MMP in lung adenocarcinoma cells was assessed. JC-1 stains low-MMP cells as green and high-MMP cells as red due to MMP-dependent accumulation of JC-1 dye in mitochondria, which results in a shift in fluorescence emission from green to red. Real-time fluorescence imaging showed that JC-1-stained lung adenocarcinoma cells had various MMP levels, which were dynamic over a 24-h period (Figure 2a and Supplementary Movie 1). The majority of high-MMP cells retained a high MMP, whereas a proportion of low-MMP cells became high-MMP cells within 24 h. After 24 h, 80% of the total number of high-MMP cells originated from high-MMP cells, and 20% originated from low-MMP cells (Figure 2b). This result suggested that lung adenocarcinoma cells could be grouped into high- and low-MMP cells and maintain their high- or low-MMP status for at least 24 h.

Figure 2.

High-MMP cells exhibit increased migration and invasion. (a) The time course of changes in the MMP of A549 cells was investigated by JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3′,3′-tetraethyl benzimidazolyl carbocyanine iodide) staining and real-time fluorescence microscopy using IncuCyte ZOOM (Essen BioScience). Cells were imaged at 2-h intervals for 24 h; a representative image is shown. Images of the entire time course are shown in Supplementary Movie 1. Red, high-MMP cells; green; low-MMP cells; black arrow, MMP-unchanged cells; white arrow, MMP-changed cells. (b) The change in MMP over 24 h was quantified. (c) A549 and H1650 cells stained with JC-1 were sorted according to their MMP level by flow cytometry using a FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cells in the highest and lowest 20% MMP categories were labelled high- and low-MMP cells, respectively. (d) The proliferation rates of high- and low-MMP cells were determined by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. (e, f) High-MMP cells exhibited increased migration and invasion. Migration and invasion of high- and low-MMP cells were assessed by Transwell migration and invasion assays. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 relative to high-MMP cells.

Cells were sorted according to their MMP level; the upper and lower 20% of cells were termed high- and low-MMP cells, respectively (Figure 2c). The difference in MMP was not significantly associated with the proliferation rate (Figure 2d), suggesting that low-MMP cells were not dead or damaged. In Transwell migration experiments, the migration of low-MMP cells was found to be inferior to that of high-MMP cells (Figure 2e). Moreover, low-MMP cells exhibited a lower invasion capacity than high-MMP cells (Figure 2f). These results suggested that high-MMP cancer cells were more likely to lead to metastasis than low-MMP cells.

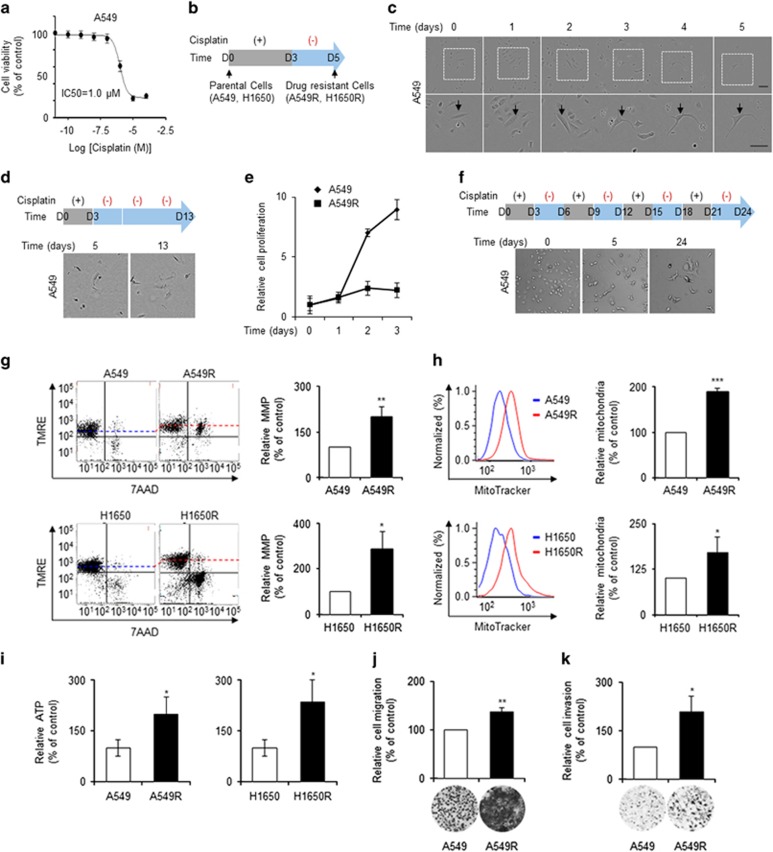

Cisplatin-resistant cells have a high MMP and exhibit increased migration and invasion

The majority of cancer cells are killed by chemotherapy; however, a small population of drug-resistant cells survive, and these can lead to metastasis. The MMP and metastasis potential of these drug-resistant cells were thus investigated. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of cisplatin, a standard chemotherapeutic, for A549 cells was 1.0 μM (Figure 3a). A549 cells were treated with 10 μM cisplatin for 3 days, followed by culture in the absence of cisplatin for 2 days (Figure 3b). The majority of A549 cells eventually underwent apoptosis; however, some cells survived after 5 days (Figure 3c and Supplementary Movie 2). Indeed, almost all cells viable on day 5 survived for further 8 days (Figure 3d). The proliferation rate of the surviving cells on day 5 was reduced greatly compared with parental cells (Figure 3e). Moreover, the surviving cells on day 5 were resistant to a further three cycles of 3-day cisplatin treatment (Figure 3f). These cells were thus considered cisplatin-resistant cells and named A549R cells. Drug-resistant H1650 cells were obtained by treatment with 5 μM cisplatin and were named H1650R cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cisplatin-resistant cells had a high MMP and increased migration and invasion. (a) A549 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of cisplatin for 3 days. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of cisplatin for A549 cells was determined by SRB assay. (b) Schematic diagram of cisplatin treatment. (c) A small population of lung adenocarcinoma cells was resistant to cisplatin treatment. A549 cells treated with cisplatin (10 μM) as indicated in b were imaged at 2-h intervals for 5 days using IncuCyte ZOOM (Essen Bioscience); a representative image is shown. Full time-course images are shown in Supplementary Movie 2. (d) After withdrawal of cisplatin, A549R cells remained viable but did not proliferate significantly. The majority existed as single cells and were viable at 10 days after cisplatin withdrawal. (e) The proliferation rates of A549 and A549R cells were determined by cell counting using Cytation 3 (Bioteck). (f) A549R cells survived a further three cycles of cisplatin treatment. (g) Cisplatin-resistant cells had a higher MMP than parental cells. The MMPs of parental (A549 and H1650) and cisplatin-resistant (A549R and H1650R) cells were investigated by tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE) staining followed by flow cytometry (FACSVerse; BD Biosciences). 7-Amino actinomycin D (7-AAD) staining was used to evaluate cell viability. (h) Cisplatin-resistant cells had a greater number of mitochondria than parental cells. Parental and cisplatin-resistant cells were stained with Mitotracker and analyzed by flow cytometry. (i) Cisplatin-resistant cells had a higher cellular ATP level than parental cells, as determined using an ATP assay kit. (j, k) Cisplatin-resistant cells exhibited increased migration and invasion, as determined by Transwell migration and invasion assays. Data are means of at least three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 relative to parental cells.

The MMP of parental (A549 and H1650) and cisplatin-resistant (A549R and H1650R) cells was measured by TMRE staining followed by flow cytometry. Cell viability was assayed using 7-AAD, a membrane-impermeable fluorescent dye that is generally excluded from viable cells. The MMP of cisplatin-resistant A549R and H1650R cells was significantly higher than that of parental A549 and H1650 cells (Figure 3g). Flow cytometry analysis using MitoTracker Green FM, which accumulates in active mitochondria, also showed that the mitochondria of cisplatin-resistant cells were more active than those of parental cells (Figure 3h). Moreover, cisplatin-resistant cells had a higher cellular ATP level than parental cells (Figure 3i). As drug-resistant cells had higher MMP and ATP levels, their migration and invasion were evaluated. A Transwell migration and invasion assay showed that drug-resistant cells exhibited increased migration and invasion compared with parental cells (Figures 3j and k).

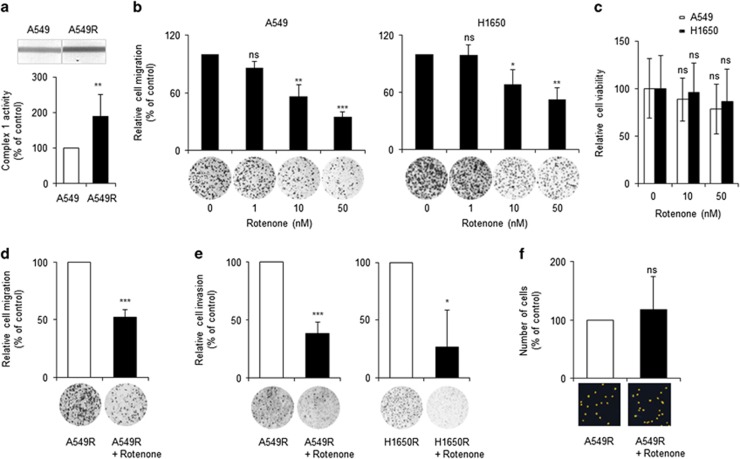

Inhibition of mitochondrial activity reduced migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells

As high-MMP cells exhibited greater migration and invasion than low-MMP cells and cisplatin-resistant cells showed a higher MMP and enhanced migration and invasion (Figures 2 and 3), the question of whether mitochondrial activity was required for the migration and invasion of drug-resistant cells was investigated. First, the effect of inhibition of mitochondrial activity on the migration of lung adenocarcinoma cells was determined. Cisplatin-resistant cells exhibited increased mitochondrial complex 1 activity compared with parental cells (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure S1). Nanomolar concentrations of Rotenone, an inhibitor of mitochondrial OxPhos complex 1,25 significantly reduced the migration of A549 and H1650 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4b). Because Rotenone at nanomolar concentrations did not cause the deaths of A549 and H1650 cells (Figure 4c) and other lung adenocarcinoma cells,26 their decreased migration was not due to a reduction in viability.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of mitochondrial activity reduced the migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells. (a) Mitochondrial complex 1 activities of A549 and A549R cells were determined by a complex 1 enzyme activity dipstick assay kit. (b) Rotenone, a mitochondria complex 1 inhibitor, inhibited the migration of lung adenocarcinoma cells in a dose-dependent manner. During migration assays of A549 and H1650 cells, Rotenone was added at the indicated doses. (c) Rotenone at low doses did not cause cell death. A549 and H1650 cells were treated with the indicated doses of Rotenone for 24 h, and cell viability was assessed using the PrestoBlue cell-viability reagent (Invitrogen). (d, e) A low dose of Rotenone inhibited the migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells. Cisplatin-resistant cells (A549R and H1650R cells) were treated with or without Rotenone (10 nM) during migration and invasion assays. (f) Rotenone did not affect the viability of cisplatin-resistant cells. A549R cells were treated with or without Rotenone (10 nM) for 3 days, and surviving cells were imaged and enumerated using Cytation 3 (Bioteck). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 relative to non-Rotenone-treated cells.

The dependence of the migration and invasion of drug-resistant cells on mitochondrial activity was next evaluated. Treatment with 10 nM Rotenone significantly reduced the migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells (Figures 4d and e). To exclude the possibility that the decreased invasion was caused by a reduction in cell viability, the effect of 10 nM Rotenone treatment on the viability of drug-resistant cells was assessed. Because a small number of cisplatin-resistant cells was used, enumeration using conventional colourimetric methods was problematic. Thus, cells were enumerated using a Cytation 3 cell-imaging microplate reader. Viable cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), a fluorescent marker of the nucleus, and imaged (Supplementary Figure S2). Treatment with Rotenone (10 nM) had no effect on the number of viable cells (Figure 4f). These results suggested that mild inhibition of mitochondrial activity reduces the migration and invasion of cisplatin-resistant cells without affecting their viability.

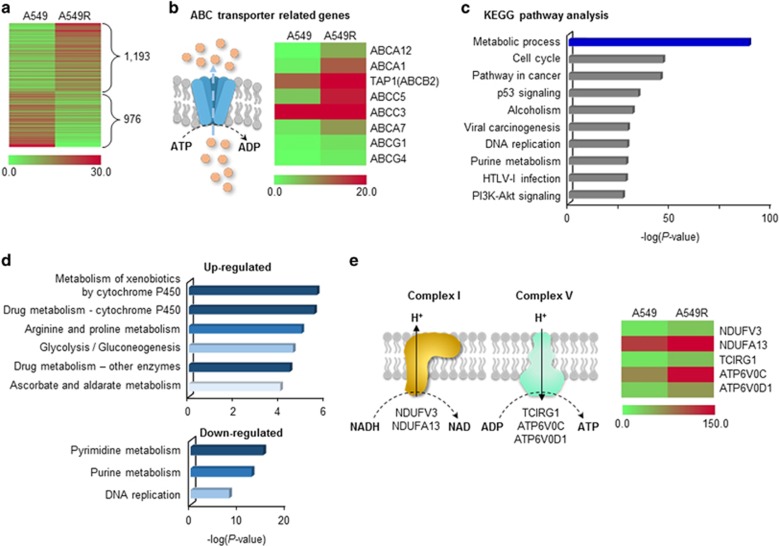

Global changes in the expression of metabolism-related genes in cisplatin-resistant cells

To evaluate the metabolism of cisplatin-resistant cells, the mRNA levels of relevant genes in A549 and A549R cells were compared using RNA-sequencing. In total, 1,193 genes were upregulated and 976 genes were downregulated more than twofold in A549R cells compared with parental A549 cells (Figure 5a). Drug efflux systems were activated in A549R cells, as indicated by upregulation of ABC transporters (Figure 5b). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis showed that differentially expressed genes were enriched in the metabolic process category (Figure 5c and Supplementary Table 2). The majority of upregulated genes were in the drug-detoxification category, and the majority of downregulated genes were related to DNA synthesis-related metabolism (Figure 5d). Among genes related to the mitochondrial OxPhos complex, all those whose expression was changed significantly were upregulated, suggesting enhancement of mitochondrial activity in cisplatin-resistant cells (Figure 5e and Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 5.

Global changes in the expression of metabolism genes in cisplatin-resistant cells. (a) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between parental and cisplatin-resistant cells (A549 and A549R cells) were analyzed by RNA sequencing. Genes whose expression changed more than twofold are shown. (b) Drug-efflux systems were activated in A549R cells. Various ABC transporters were upregulated in A549R cells. (c) Metabolic process was the dominant pathway altered in A549R cells according to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. The top 10 pathways are presented; full analysis results are shown in Supplementary Table 2. (d) Drug detoxification and DNA synthesis-related metabolism were up- and downregulated, respectively, in A549R cells. Up- and downregulated DEGs in the metabolic process category were subjected to KEGG pathway analysis. Pathway maps with a P-value <1 × 10−4 are shown. (e) Genes related to OxPhos-complexes I and V were upregulated in A549R cells. All DEGs related to the OxPhos complexes whose expression changed more than twofold are shown.

Discussion

Intratumoural heterogeneity and cancer stemness are the principal causes of failure of cancer therapy. In many cases, a small population of drug-resistant cells survives after first-line standard therapy, which can lead to metastasis and recurrence. Identification of the difference in metabolism between drug-resistant and parental cells might suggest a method of eradicating the former. In this study, the MMP of cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells was increased (Figure 3). In addition, KEGG pathway analysis of RNA-sequencing data showed that the expression of mitochondrial membrane genes was upregulated in cisplatin-resistant compared with parental cells (Figure 5). These results suggested that drug-resistant cells are more reliant on mitochondria for energy production compared with parental cells.

The lung cancer cells showed diverse mitochondrial activity, as determined by JC-1 and TMRE staining (Figure 2). The time course of changes in the MMP in lung cancer cells has not been reported previously. In this study, the time required for the MMP of individual cells to change was determined in a semi-quantitative manner (Figures 2a and b). The data suggested that the MMP of lung adenocarcinoma cells did not change greatly during performance of Transwell migration/invasion assays, which were 12–16 h in duration. The Transwell migration/invasion assay results showed that high-MMP cells exhibited greater migration and invasion than low-MMP cells. This finding is consistent with previous reports that colon and metastatic breast cancer cells with higher MMPs have greater invasive potential.27, 28

The drug-resistant cells that survive drug treatment enter dormancy.29, 30 As a result of persistent drug treatment, a fraction of these cells produce colonies of cells with relatively stable tolerance, and these exit dormancy.30 In this study, the drug-resistant cell population was isolated by treatment with cisplatin for 3 days and a further 2 days of culture in the absence of cisplatin (Figure 3). The isolated cells continued to survive but did not proliferate (Figures 3d and e), suggesting that they were dormant. Because cisplatin affects mitochondria,31 the MMP was measured 2 days after the removal of cisplatin to exclude the possibility of drug-induced changes in the MMP. The MMP of cisplatin-resistant dormant cells was higher than that of the parental cells (Figure 3). Because dormant, drug-resistant and stem-cell-like populations of breast cancer cells are dependent on mitochondria for energy production,13 the relationship between MMP and drug resistance is likely not limited to NSCLC. Further investigation of changes in MMP among parental cells, dormant drug-resistant cells and drug-resistant cells that have exited from dormancy will provide further information on the relationship between MMP and drug resistance.

Mitochondria have been linked to metastasis32, 33 due to their production of reactive oxygen species, and the effect of inhibition of mitochondrial complex 1 on metastasis is unclear. Inhibition of mitochondrial complex 1 by gene knockdown has been reported to promote migration.34 However, metformin, a complex 1 inhibitor,35 was found to suppress metastasis of breast cancer,36 ovarian cancer37 and melanoma.38 In this study, Rotenone, a specific inhibitor of complex 1,25 inhibited the migration/invasion of not only the overall population but also the drug-resistant population of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Treatment with nanomolar concentrations of Rotenone inhibited migration/invasion without affecting cell viability (Figure 4). Because 5 and 10 nM Rotenone inhibited complex 1 activity by ~11% and ~33%, respectively,39 and a micromolar concentration of Rotenone is required to reduce the viability of NSCLC cells,26 a slight reduction in mitochondrial complex 1 activity might affect metastasis but not cell viability. Although many inhibitors of mitochondria are toxic, therapeutic windows exist for their use against cancer.40, 41, 42 Thus, these findings suggest that inhibitors of mitochondria can be used to reduce the incidence of metastasis after platinum-based therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tae Sik Kim of the Flow Cytometry Core (National Cancer Center) for his expert assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC-1410670 and NCC-1610190) and by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2014R1A1A2058486).

Author contributions

JHJ, DKK and YS: collection and assembly of data, data analysis, interpretation and writing of draft; HYK, BS, EYL and JKK: collection of data; HJY, HC, DHS, STK, JHC and SYK: data analysis and interpretation; HJ: conception, design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Experimental & Molecular Medicine website (http://www.nature.com/emm)

Supplementary Material

References

- Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat 2016; 48: 436–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Liu SV, Subramaniam DS, Giaccone G. Refining the treatment of NSCLC according to histological and molecular subtypes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015; 12: 511–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JY, Jang SH. Epidemiology of lung cancer in Korea: recent trends. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2016; 79: 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 14: 275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtova AV, Xiao J, Mo Q, Pazhanisamy S, Krasnow R, Lerner SP et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer chemoresistance. Nature 2015; 517: 209–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DA, Bhakta NR, Kessenbrock K, Prummel KD, Yu Y, Takai K et al. Single-cell analysis reveals a stem-cell program in human metastatic breast cancer cells. Nature 2015; 526: 131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 2011; 331: 1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanchi I, Santamaria-Martinez A, Susanto E, Peng H, Lehr HA, Delaloye JF et al. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature 2012; 481: 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144: 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer's Achilles' heel. Cancer Cell 2008; 13: 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Yang J, Lee E, Cheong JH. Metabolism in embryonic and cancer stemness. Arch Pharm Res 2015; 38: 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasto A, Bellio C, Pilotto G, Ciminale V, Silic-Benussi M, Guzzo G et al. Cancer stem cells from epithelial ovarian cancer patients privilege oxidative phosphorylation, and resist glucose deprivation. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 4305–4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBleu VS, O'Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis MC et al. PGC-1alpha mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16: 992–1003, 1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song IS, Jeong YJ, Jeong SH, Heo HJ, Kim HK, Bae KB et al. FOXM1-induced PRX3 regulates stemness and survival of colon cancer cells via maintenance of mitochondrial function. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 1006-16.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Jang H, Kim TW, Kang BH, Lee SE, Jeon YK et al. Core pluripotency factors directly regulate metabolism in embryonic stem cell to maintain pluripotency. Stem Cells 2015; 33: 2699–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek AR, Lee CH, You HJ. A role of zinc-finger protein 143 for cancer cell migration and invasion through ZEB1 and E-cadherin in colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinogen 2014; 53(Suppl 1): E161–E168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Lee SH, Lee JS, Nam B, Seong TW, Son J et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition combined with phenformin treatment reversed NSCLC through ATP depletion. Oncotarget, (e-pub ahead of print 30 June 2016; doi:10.18632/oncotarget). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Kim N, Kim SJ, Song J, Gong YD, Kim SY. Anti-cancer effect of a quinoxaline derivative GK13 as a transglutaminase 2 inhibitor. J Cancer Res Clin 2013; 139: 1279–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Choi DE, Kim H, Cho EJ, Youn HD. Cabin1 represses MEF2 transcriptional activity by association with a methyltransferase, SUV39H1. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 11172–11179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lanczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e82241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NP, Schulze A. Targeting cancer metabolism—aiming at a tumour's sweet-spot. Drug Discov Today 2012; 17: 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Locasale JW, Bielas JH, O'Sullivan J, Sheahan K, Cantley LC et al. Heterogeneity of tumor-induced gene expression changes in the human metabolic network. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31: 522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell 2006; 127: 679–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov AV, Margreiter R. Heterogeneity of mitochondria and mitochondrial function within cells as another level of mitochondrial complexity. Int J Mol Sci 2009; 10: 1911–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Choi AY, Yoon H, Choe W, Yoon KS, Ha J et al. Baicalein protects HT22 murine hippocampal neuronal cells against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species production and CHOP induction. Exp Mol Med 2010; 42: 811–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YL, Feng S, Chen W, Hua ZC, Bian JJ, Yin W. Mitochondrial inhibitor sensitizes non-small-cell lung carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by reactive oxygen species and Bcl-X(L)/p53-mediated amplification mechanisms. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5: e1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. The intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential of colonic carcinoma cells is linked to the probability of tumor progression. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 9861–9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston MA, Augenlicht LH, Heerdt BG. Stable differences in intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential of tumor cell subpopulations reflect phenotypic heterogeneity. Int J Cell Biol 2011; 2011: 978583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell 2010; 141: 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita Y, Kalir T, Rahaman J, Dottino P, Kohtz DS. Alterations in nuclear pore architecture allow cancer cell entry into or exit from drug-resistant dormancy. Am J Pathol 2012; 180: 375–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Schumaker LM, Egorin MJ, Zuhowski EG, Guo Z, Cullen KJ. Cisplatin preferentially binds mitochondrial DNA and voltage-dependent anion channel protein in the mitochondrial membrane of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: possible role in apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 5817–5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porporato PE, Payen VL, Perez-Escuredo J, De Saedeleer CJ, Danhier P, Copetti T et al. A mitochondrial switch promotes tumor metastasis. Cell Rep 2014; 8: 754–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Flomenberg N, Birbe RC, Witkiewicz AK et al. Mitochondrial metabolism in cancer metastasis: visualizing tumor cell mitochondria and the ‘reverse Warburg effect' in positive lymph node tissue. Cell Cycle 2012; 11: 1445–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zhou A, Lu H, Chen Y, Huang G, Yue X et al. Suppression of mitochondrial complex I influences cell metastatic properties. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e61677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton WW, Weinberg SE, Hamanaka RB, Soberanes S, Sullivan LB, Anso E et al. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. Elife 2014; 3: e02242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufi S, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Lopez-Bonet E et al. The anti-diabetic drug metformin suppresses the metastasis-associated protein CD24 in MDA-MB-468 triple-negative breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2011; 25: 135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan R, Graham RP, Maguire JL, Giri S, Shridhar V. Metformin suppresses ovarian cancer growth and metastasis with enhancement of cisplatin cytotoxicity in vivo. Neoplasia 2011; 13: 483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo M, Tichet M, Abbe P, Ohanna M, Lehraiki A, Rouaud F et al. Metformin blocks melanoma invasion and metastasis development in AMPK/p53-dependent manner. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12: 1605–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Kruse SE, Palmiter RD, Xia Z. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition is not required for dopaminergic neuron death induced by rotenone, MPP+, or paraquat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 15136–15141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg SE, Chandel NS. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Chem Biol 2015; 11: 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pages M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016, (e-pub ahead of print 4 May 2016; doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.60.

- Vander Heiden MG. Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10: 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.