Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Improving provider recommendations is critical to addressing low human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage. Thus, we sought to determine the effectiveness of training providers to improve their recommendations using either presumptive “announcements” or participatory “conversations.”

METHODS:

In 2015, we conducted a parallel-group randomized clinical trial with 30 pediatric and family medicine clinics in central North Carolina. We randomized clinics to receive no training (control), announcement training, or conversation training. Announcements are brief statements that assume parents are ready to vaccinate, whereas conversations engage parents in open-ended discussions. A physician led the 1-hour, in-clinic training. The North Carolina Immunization Registry provided data on the primary trial outcome: 6-month coverage change in HPV vaccine initiation (≥1 dose) for adolescents aged 11 or 12 years.

RESULTS:

The immunization registry attributed 17 173 adolescents aged 11 or 12 to the 29 clinics still open at 6-months posttraining. Six-month increases in HPV vaccination coverage were larger for patients in clinics that received announcement training versus those in control clinics (5.4% difference, 95% confidence interval: 1.1%–9.7%). Stratified analyses showed increases for both girls (4.6% difference) and boys (6.2% difference). Patients in clinics receiving conversation training did not differ from those in control clinics with respect to changes in HPV vaccination coverage. Neither training was effective for changing coverage for other vaccination outcomes or for adolescents aged 13 through 17 (n = 37 796).

CONCLUSIONS:

Training providers to use announcements resulted in a clinically meaningful increase in HPV vaccine initiation among young adolescents.

What’s Known on This Subject:

National guidelines recommend routine human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for all 11- or 12-year-olds; however, vaccine coverage in the United States is persistently low. Provider recommendation for HPV vaccination is critical for motivating uptake.

What This Study Adds:

Training providers to use announcements resulted in a clinically meaningful increase in HPV vaccine initiation among 11- and 12-year-olds. Training providers to start participatory conversations did not increase HPV vaccine initiation coverage beyond secular trends.

The United States first licensed human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine a decade ago,1 but only 34% of girls and 21% of boys aged 13 to 15 had completed the 3-dose series by 2014.2 These levels fall far short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage.3 The President’s Cancer Panel described this shortfall as “a serious but correctable threat to progress against cancer.”4 An important target for intervention is HPV vaccine initiation as most adolescents who start the series complete it.2

A high-quality recommendation by a health care provider is a uniquely potent motivator of HPV vaccine uptake,5,6 yet many providers make these recommendations hesitantly, late, or not at all.5,7–9 Provider concerns include the time it takes to recommend the vaccine,10–12 anticipation of an uncomfortable conversation related to sex5,13,14 and a false perception that parents do not value HPV vaccination.5,15 One intriguing approach to addressing these issues is to use presumptive “announcements,” or brief statements that assume parents are ready to vaccinate. Announcements are commonly used for early childhood vaccines and other routine clinical care. Furthermore, analyses of videotaped clinician encounters16,17 and a nationally representative survey18 suggest that announcements are associated with higher vaccine uptake. Alternatively, a “conversation” approach that engages parents in open-ended discussions may build rapport and thus increase parental openness to HPV vaccination for their children.19 Although a previous trial did not find evidence that conversations improve parents’ vaccination attitudes, the impact of the approach on vaccination outcomes has not been tested.19

In the absence of previously published randomized trials, it is unclear whether providers who are trained to improve their recommendations using announcements or conversations are more successful in increasing HPV vaccination coverage compared with providers who do not receive such training. We hypothesized that either announcement training or conversation training would lead to larger increases in HPV vaccination coverage compared with no training.

Methods

Participants

We sought to enroll 30 primary care clinics into the trial. Clinics were eligible to enroll if they specialized in pediatric or family medicine; had 100 or more patients aged 11 or 12 attributed to the clinic in the North Carolina Immunization Registry (NCIR) as of March 2014; were located within a 2-hour drive of Chapel Hill, North Carolina; and had at least 1 pediatric or family medicine physician who provided HPV vaccine to adolescents aged 11 or 12. Clinics were ineligible for the trial if they had taken part in quality improvement efforts to increase HPV vaccination rates in the previous 6 months or planned to do so over the next 6 months. We identified 150 eligible clinics based on NCIR data.

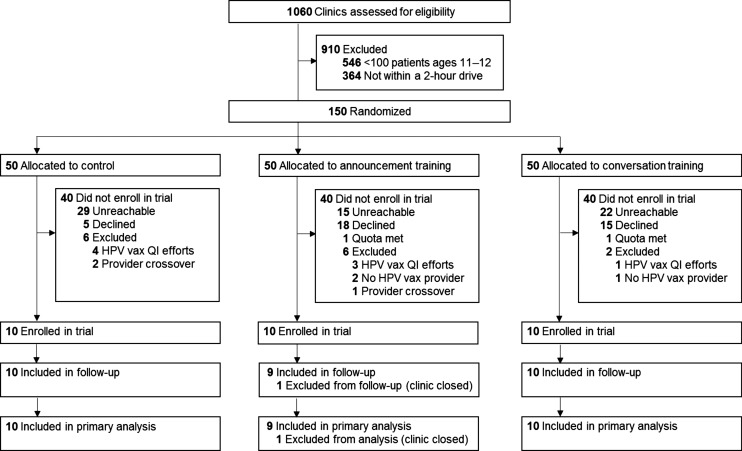

The parallel-group trial design had 3 arms: announcement training, conversation training, or control. A biostatistician unaffiliated with the trial used a 1:1:1 allocation ratio to randomize to trial arm, stratifying clinics based on their patient volume (Fig 1). Between March and August 2015, we conducted recruitment efforts until we met the trial quota of 10 clinics enrolled per arm. When a clinic expressed interest in participating, we determined whether vaccine-prescribing clinicians practiced at clinics randomized to different trial arms (ie, provider crossover) and included only the eligible clinic appearing first on our list, excluding the other clinic from the trial. Although clinics could not be blinded as to whether they received a training, we did not alert them ahead of the training as to which strategy they would learn. Patients were unaware of the training of providers. Of the clinics that did not enroll, 66 were unreachable, 38 declined, 14 were excluded (8 had participated or were planning to participate in HPV vaccination quality improvement efforts, 3 did not have an HPV vaccine prescriber, 3 had provider crossover), and 2 expressed interest after we met the trial’s clinic enrollment quota. Compared with clinics in the intervention arms, fewer control arm clinics declined trial participation and more were unreachable. The number of 11- or 12-year-olds attributed to enrolled clinics and unenrolled clinics did not differ as of March 2014. Providers consented to be in the trial before the start of training sessions.

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow diagram. QI, quality improvement; vax, vaccine.

Procedures

From May to August 2015, a physician educator traveled to intervention clinics to deliver the 1-hour trainings to vaccine-prescribing clinicians (eg, physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) and other clinic staff, who may support parents’ decisions to vaccinate their children. Providers received up to 1 prescribed continuing medical education credit for attending the training. Intervention clinics received up to $800 and control clinics received $200. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the trial protocol.

Intervention

Formative Research

To inform the development of the announcement and conversation trainings, we conducted formative research that included national surveys of US primary care physicians5,11 and parents of adolescents.6 We integrated the surveys’ findings with other published findings and feedback from an expert panel of pediatricians, family physicians, other vaccine providers, and researchers. These experts did not practice at our pilot or trial clinics. In April 2015, we piloted our trainings in 2 clinics, conducted follow-up phone calls with 3 of the clinics’ vaccine-prescribing clinicians to gather additional feedback, reviewed posttraining satisfaction surveys, and refined the trainings.

Training Content

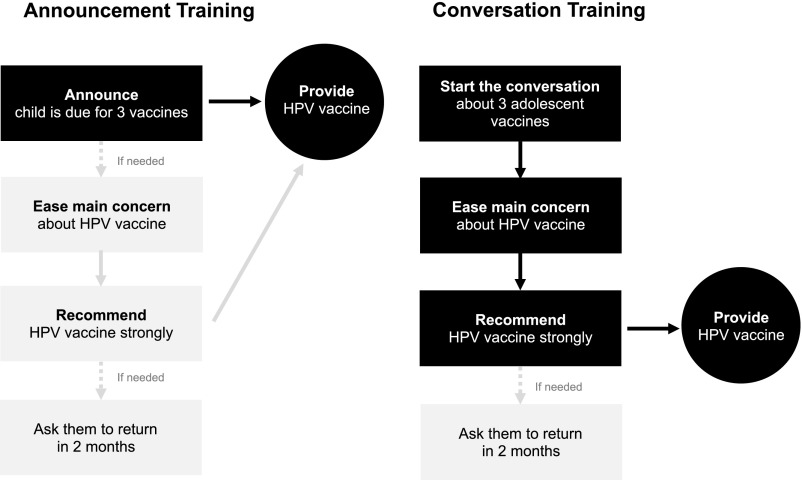

The announcement training, informed by the work of Opel and colleagues,16,17 included the steps shown in Fig 2A. The darker boxes indicate requisite steps for delivering announcements, whereas lighter boxes are necessary only if the previous step did not result in HPV vaccination. We instructed providers to first announce that the child is due for 3 vaccines to be given today. Key elements of this first step included providers mentioning the child’s age; announcing the child is due for 3 vaccines recommended for children this age, placing HPV vaccine in the middle of list; and saying they will vaccinate today (Supplemental Fig 3). Only if parents raised a concern would providers then identify and ease parents’ main concern about HPV vaccine, using a structured approach20 and strongly recommending same-day HPV vaccination. Key elements of this final step included providers giving a motivational statement, ending with the phrase “I recommend …” and encouraging parents to get HPV vaccine that day (Supplemental Fig 3).

FIGURE 2.

Announcement and conversation training content.

In contrast, the conversation training built on the principles of shared decision making. It differed from the announcement training primarily in the first step. We instructed providers to first start the conversation about 3 adolescent vaccines. Key elements of this first step included providers introducing the 3 vaccines recommended for children this age, placing HPV vaccine in the middle of the list to deemphasize it and make it routine,21 discussing the health benefits of these vaccines, and inviting parents’ questions while saving the recommendation for later in the conversation (Fig 2B).

For both trainings, we provided general advice on addressing common problems posed by HPV vaccine communication. For instance, if parents associated the vaccine with sex, we suggested providers redirect the conversation to be about cancer prevention. If parents asked which vaccines are required for school attendance and which are optional, we suggested providers redirect the conversation by saying they strongly recommend all 3 adolescent vaccines. Both trainings suggested providers ask parents who did not agree to vaccination to return in 2 months to further discuss vaccination.

Training Procedures

The physician educator used a standardized script and PowerPoint slide set to lead the 4-part training. The first section, “Review Evidence,” was a didactic review of the latest research on HPV vaccination practices, HPV vaccine effectiveness, safety, and the rationale for targeting younger adolescents. In the second section, “Build Skills,” the physician educator taught participants how to deliver effective HPV vaccine recommendations using either announcements or conversations, depending on the training. This section included step-by-step instruction as well as a demonstration. In the third section, “Practice,” the physician educator gave participants a note card that outlined relevant steps and asked them to complete a brief exercise to adapt the suggested material to their own personal style and language (Supplemental Fig 3). This section included role-play with a colleague and discussion about the benefits and challenges of using announcements or conversations. In the fourth section, “Application to Your Practice,” the physician educator engaged participants in a discussion of how they would apply the training to their clinical practice, allowing them to align their communication as a group.

After the training, vaccine-prescribing clinicians agreed to use announcements or conversations to recommend HPV vaccination for at least 5 vaccine-eligible patients within 2 weeks.22 We asked that participants not share the training content outside their clinics. Clinics in the waitlist control condition received a video recording of the announcement training, which was sent 1 month after the 6-month assessment of vaccination outcomes.

Measures

NCIR provided clinic-level data on vaccination coverage, specialty, patient volume (ie, count of patients attributed to the clinic in NCIR), patient sex, and patients’ eligibility for publicly funded vaccines (Table 1). Used by >90% of vaccine providers in the state, NCIR is a secure, Web-based registry that contains immunization information for almost all North Carolina adolescents.23,24 NCIR had vaccination data for the highest percentage of adolescents of any state as of 2013.24 NCIR provides data on vaccination status, attributing all vaccine doses to the clinic at which the adolescent is a patient at the time of data collection. We calculated changes in vaccine coverage, from baseline to 3 months and 6 months posttraining at the clinic, among adolescents aged 11 or 12 and 13 through 17. We matched the trial arms on timing of trainings and assessments to control for seasonal variation in vaccination. Vaccine coverage was assessed for the cohort of adolescents attributed to each clinic as of 6-months postintervention. We assessed coverage for the following vaccines: HPV initiation (≥1 dose); HPV completion (3 doses); tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap); and meningococcal conjugate (≥1 dose). The primary trial outcome was change in HPV vaccination initiation between baseline and 6-months post-intervention for adolescents ages 11 or 12. The remaining vaccination outcomes were secondary trial outcomes. We used data for a single cohort in each clinic, although some adolescents may not have had a visit with their provider during this 6-month trial period.

TABLE 1.

Clinic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Control (10 Clinics) | Announcement Training (9 Clinics) | Conversation Training (10 Clinics) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic specialty, k (%) | ||||

| Pediatric | 6 (60) | 7 (78) | 9 (90) | .32 |

| Family practice | 4 (40) | 2 (22) | 1 (10) | |

| Adolescent patient load, mean (SD) | ||||

| Ages 11 or 12 | 600 (689) | 476 (422) | 690 (340) | .66 |

| Ages 13–17 | 1454 (1511) | 1004 (906) | 1422 (737) | .63 |

| All ages (11–17) | 2053 (2190) | 1479 (1327) | 2112 (1073) | .65 |

| Vaccine prescribers at clinic | 6.5 (5.7) | 4.6 (3.4) | 5.3 (2.7) | .59 |

| Sex of patients, mean proportion (SD) | ||||

| Male | 0.50 (0.02) | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.47 (0.03) | .12 |

| Female | 0.47 (0.02) | 0.46 (0.02) | 0.48 (0.03) | .30 |

| Not specified | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | .51 |

| Vaccine dose funding,a mean proportion (SD) | ||||

| Private/North Carolina Health Choice | 0.62 (0.19) | 0.57 (0.22) | 0.73 (0.19) | .25 |

| Public | 0.38 (0.19) | 0.43 (0.22) | 0.27 (0.19) | .25 |

| Baseline vaccination coverage, patients aged 11 or 12, % | ||||

| HPV, ≥1 dose | 30.0 | 25.5 | 21.3 | <.01* |

| HPV, 3 doses | 8.8 | 6.4 | 5.6 | <.01* |

| Tdap | 72.7 | 66.4 | 68.1 | <.01* |

| Meningococcal | 52.8 | 51.5 | 52.0 | .42 |

| Baseline vaccination coverage, patients aged 13–17, % | ||||

| HPV, ≥1 dose | 60.9 | 54.4 | 51.7 | <.01* |

| HPV, 3 doses | 37.1 | 30.4 | 30.2 | <.01* |

| Tdap | 93.7 | 91.2 | 88.8 | <.01* |

| Meningococcal | 84.8 | 81.3 | 77.6 | <.01* |

Analyses of baseline vaccination rates weighted for patient volume.

Privately funded vaccines are funded by insurance and North Carolina Health Choice. Publicly funded doses include those funded by Vaccines for Children (American Indian/Alaska Native, Medicaid, uninsured, underinsured, and Title X).

P < .01.

Statistical Analysis

Power analyses assumed each trial arm would have 10 clinics that served 5000 adolescents aged 11 or 12, baseline HPV vaccine initiation coverage of 45%, α = .05. We estimated 80% power to detect a 2.7% difference between the control and each intervention arm in HPV vaccine initiation coverage from baseline to follow-up. Analyses of trial data used a modified intent-to-treat approach that included enrolled clinics with data available at baseline and 6-months postintervention. To assess whether clinic characteristics differed by trial arm, we used Fisher’s exact test and analysis of variance. To analyze intervention effects, we performed mixed-level Poisson regressions for each vaccination outcome, modeling the change in vaccine coverage from baseline to 3- and 6-month follow-up at the level of the patient. Regression models included a random intercept to account for unobserved heterogeneity among clinics as well as an offset variable equal to the log of the number of adolescent patients at each clinic. Analyses accounted for clustering of data by clinic. We report unadjusted proportions for vaccine coverage data at 3 and 6 months posttraining. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC), using 2-tailed tests and a critical α = .05.

Results

Clinic Characteristics

Of the 30 clinics enrolled in the trial, 29 had accessible data for 3- and 6-month vaccine coverage assessments (1 clinic that received announcement training closed before follow-up assessments). No clinics or participants withdrew due to adverse events. Most were pediatric clinics (76%). As of 6 months posttraining, NCIR attributed 17 173 adolescents aged 11 or 12 and 37 796 adolescents aged 13 through 17 to the clinics. A mean of 5 (range 2–12) vaccine prescribers practiced at each clinic. Trial arms did not differ on these clinic characteristics but did differ with respect to baseline vaccination coverage (Table 1). Of vaccine prescribers at intervention clinics, attendance was 90% for announcement trainings and 89% for conversation trainings. Of vaccine prescribers who attended trainings, 92% were present for the majority (ie, at least three-quarters) of the announcement training, and 99% were present for the majority of the conversation training. As is typical, some clinics received quality improvement visits from the state immunization branch during the follow-up period (2 that received announcement training, 3 that received conversation training, and 3 in the control arm).

Trial Outcomes

Clinics that received announcement training had increases in HPV vaccine initiation coverage at 6 months for 11- or 12-year-olds that exceeded control clinics’ increases (5.4% difference, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1% to 9.7%), the primary trial outcome (Table 2). This difference represents 37 more patients who initiated HPV vaccination. Sex-stratified analyses also showed greater increases in coverage at 6 months among girls (4.6% difference, 95% CI 0.1% to 9.0%) and among boys (6.2% difference, 95% CI 1.5% to 11.0%). These increases were already observable by 3 months for 11- or 12-year-olds overall (5.1% difference, 95% CI 2.0% to 8.2%), as well as for girls (4.8% difference, 95% CI 1.6% to 8.0%) and boys (5.6% difference, 95% CI 2.0% to 9.1%) separately.

TABLE 2.

HPV Vaccine Coverage Among Patients Aged 11 or 12 Years, 3- and 6-Month Posttraining (n = 17 173).

| 3-Months Posttraining | 6-Months Posttraining | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage at 3 Mo (%)a | Coverage Change Over Previous 3 Mo (%)b | Difference From Control (%) (95% CI)b | P | Coverage at 6 Mo (%)a | Coverage Change Over Previous 6 Mo (%)b | Difference From Control (%) (95% CI)b | P | |

| ≥1 dose | ||||||||

| Control | 37.3 | 6.4 | Reference | — | 41.2 | 9.5 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 38.0 | 11.5 | 5.1 (2.0 to 8.2) | .003* | 42.0 | 14.9 | 5.4 (1.1 to 9.7) | .02* |

| Conversation | 30.3 | 8.4 | 2.0 (–0.4 to 4.4) | .10 | 33.7 | 11.5 | 2.0 (–1.4 to 5.5) | .24 |

| ≥1 dose to girls | ||||||||

| Control | 39.6 | 7.2 | Reference | — | 44.0 | 11.2 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 41.0 | 12.0 | 4.8 (1.6 to 8.0) | .004* | 45.2 | 15.7 | 4.6 (0.1 to 9.0) | .045* |

| Conversation | 33.0 | 8.8 | 1.5 (–0.9 to 4.0) | .21 | 36.4 | 11.9 | 0.7 (–2.9 to 4.3) | .69 |

| ≥1 dose, boys | ||||||||

| Control | 35.7 | 6.0 | Reference | – | 39.2 | 8.4 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 35.8 | 11.6 | 5.6 (2.0 to 9.1) | .003* | 39.7 | 14.7 | 6.2 (1.5 to 11.0) | .01* |

| Conversation | 28.3 | 8.1 | 2.1 (–0.5 to 4.8) | .11 | 31.9 | 11.3 | 2.8 (–0.9 to 6.6) | .13 |

| 3 doses | ||||||||

| Control | 11.5 | 1.9 | Reference | — | 13.5 | 3.6 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 9.2 | 2.6 | 0.7 (–0.7 to 2.1) | .32 | 10.7 | 3.9 | 0.3 (–1.8 to 2.3) | .81 |

| Conversation | 7.2 | 1.5 | −0.4 (–1.4 to 0.7) | .48 | 9.2 | 3.3 | −0.3 (–2.1 to 1.5) | .71 |

| 3 doses, girls | ||||||||

| Control | 12.6 | 2.1 | Reference | — | 14.7 | 4.0 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 11.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 (–0.5 to 2.4) | .21 | 12.9 | 4.3 | 0.3 (–1.9 to 2.4) | .81 |

| Conversation | 8.9 | 2.0 | 0.0 (–1.1 to 1.1) | .97 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 (–2.0 to 1.9) | .97 |

| 3 doses, boys | ||||||||

| Control | 10.6 | 1.8 | Reference | — | 12.5 | 3.3 | Reference | — |

| Announcement | 7.5 | 2.1 | 0.3 (–1.3 to 1.8) | .70 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 0.1 (–2.3 to 2.4) | .96 |

| Conversation | 5.9 | 1.2 | −0.6 (–1.8 to 0.6) | .28 | 7.6 | 2.7 | −0.6 (–2.6 to 1.4) | .55 |

Vaccine coverage is unadjusted.

Three- and 6-month coverage change and comparisons among trial arms are adjusted for clustering at the clinic level.

P < .05.

Clinics that received conversation training did not differ from the control arm on coverage change for HPV vaccine initiation among adolescents ages 11 or 12 (all Ps > .05). Intervention arms did not differ from the control arm with respect to other ages (adolescents aged 13 through 17) or other vaccination coverage, including HPV series completion, Tdap, and meningococcal (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

A decade after HPV vaccine licensure, coverage remains low, in part because of missed opportunities for providers to recommend the vaccine.25 Our trial found that a brief, 1-hour training in using announcements increased coverage for HPV vaccine initiation by 5 percentage points over the control for 11- and 12-year-old adolescents. Training providers to start recommendations with a participatory conversation did not increase coverage.

Researchers have used various names for announcements, including “paternalistic,” “presumptive,” and “efficient communication.” We prefer the term “announcement” as it describes the communication behavior impartially. Our findings are consistent with observational studies that suggest announcements encourages vaccination, a hypothesis first advanced by Opel.16,17 In an analysis of 111 videotaped provider-parent discussions, parental acceptance of early childhood vaccines was more common when providers started their communication using what Opel called a “presumptive format.”16,17 Similarly, Moss and colleagues found that among a probability sample of 4121 parents of adolescents from the National Immunization Survey—Teen, HPV vaccination coverage was higher among adolescent girls of parents who recalled “efficient” provider communication about HPV vaccination than those who recalled participatory discussions.18 We speculate that announcements normalize HPV vaccination for both providers and parents, making providers more likely to raise the topic and parents more likely to consent to vaccination. In contrast, our conversation training did not increase HPV vaccine initiation. This outcome mirrors the findings of a trial by Henrikson and colleagues who found that participatory communication training was ineffective in reducing hesitant attitudes toward early childhood vaccination, as assessed by a survey of 347 mothers.19

The absence of change for 3-dose HPV vaccine series completion observed in the current trial may be due to the intervention’s focus on vaccine initiation, the 6-month follow-up period, and a decline in visits to a provider. We speculate an absence of change in vaccine coverage among older adolescents may also be due, in part, to a decline in visits to a provider. Our intervention sought to change provider behavior during a clinical encounter but not to change the frequency of clinic visits.

By achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in HPV vaccine initiation coverage, the announcement training fills an important gap. Providers describe needing a brief recommendation approach that avoids discussing sex and gives parents an opportunity to ask questions should they wish to, issues that our trainings addressed.14 Additional research is needed to better understand how trainings improve coverage and the extent to which providers use announcements in routine clinical practice.

Strengths of our trial include an effective, brief, and standardized intervention; having clinic-provided data on vaccination; and having a large sample of vaccine-eligible adolescents at trial clinics. We chose a physician to deliver the trainings, but future research will need to establish whether educators with different backgrounds would be as effective. A benefit of holding trainings at providers’ own clinics is that it allowed most members of health care teams to attend, but we do not know what impact the trainings would have in other settings, such as a national meeting, or other modes, such as a webinar. Although our trial was conducted in larger clinics in urban and rural areas of 1 Southeastern US state, we do not know whether the findings will generalize to other areas of the US, to large managed-care organizations, to smaller clinics, or to clinics that do not use immunization registries. Trial findings may represent more motivated clinics as many eligible clinics were unreachable or declined. We attempted to limit contamination by randomizing at the clinic level, randomizing before recruiting, and discouraging participants from sharing the strategy outside their clinics. It is possible that some spillover occurred, and if it did, our evaluation would underestimate the effects of the intervention. Differences by trial arm in baseline vaccination coverage also may have affected the magnitude of the observed intervention effect. Future research can extend the present trial by comparing the effectiveness of announcement training in clinics with low and high vaccination coverage. We did not assess clinics’ use of electronic health records nor clinicians’ adherence to recommendation approaches through visit observation. Research is needed to identify how parents and their adolescent children respond to announcements. Although our evaluation focused on how best to first raise the topic of vaccination, research is also needed on effective ways to ease concerns that parents may express.

Conclusions

A brief training in improving HPV vaccine recommendations using announcements increased HPV vaccine initiation among adolescents at the recommended ages for routine vaccination. Our findings support training providers to use announcements as an approach to address low HPV vaccination uptake in primary care clinics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marcy Boynton, Katrina Donahue, Margaret Gichane, Madeline Mitchell, Jennifer Morgan, Kathryn Peebles, and Parth Shah for assistance with the trial. They received no compensation for their contributions beyond that received in the normal course of their employment.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- NCIR

North Carolina Immunization Registry

- Tdap

tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis

Footnotes

Dr Brewer conceptualized and designed the trial; designed the data collection instruments; wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; and supervised the trial; Ms Hall conceptualized and designed the trial; designed the data collection instruments; acquired the data; and wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Malo conceptualized and designed the trial; designed the data collection instruments; acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Gilkey conceptualized and designed the trial; designed the data collection instruments; and wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; Ms. Quinn acquired the data and wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Lathren conceptualized and designed the trial and wrote, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT NCT02377843).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Research reported in this publication was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer and training grants from the National Cancer Institute (grants R25 CA57726 and K22 CA186979). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the trial; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Brewer reports receiving commercial research grants from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and serving on a paid advisory board for Merck. Dr Brewer did not use Merck resources to support this trial. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) . Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(29):784–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthy People 2020. Immunization and infectious diseases. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed May 2, 2016

- 4.National Cancer Institute Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake: Urgency for Action to Prevent Cancer. A Report to the President of the United States from the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McRee AL, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(6):541–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison MA, Hurley LP, Markowitz L, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives about HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20152488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Reiter PL, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk geographic area. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(3):197–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, et al. Missed clinical opportunities: provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11–12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine. 2011;29(47):8634–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilkey MB, Moss JL, Coyne-Beasley T, Hall ME, Shah PD, Brewer NT. Physician communication about adolescent vaccination: How is human papillomavirus vaccine different? Prev Med. 2015;77:181–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: a survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander AB, Best C, Stupiansky N, Zimet GD. A model of health care provider decision making about HPV vaccination in adolescent males. Vaccine. 2015;33(33):4081–4086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healy CM, Montesinos DP, Middleman AB. Parent and provider perspectives on immunization: are providers overestimating parental concerns? Vaccine. 2014;32(5):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1998–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss JL, Reiter PL, Rimer BK, Brewer NT. Collaborative patient-provider communication and uptake of adolescent vaccines. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henrikson NB, Opel DJ, Grothaus L, et al. Physician communication training and parental vaccine hesitancy: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer A. Making the CASE for vaccines: communicating about vaccine safety. Available at: www.vicnetwork.org/2010/09/22/making-the-case-for-vaccine/. Accessed February 15, 2016

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention You Are the Key to HPV Cancer Prevention [PowerPoint slides]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/speaking-colleagues.html. Accessed September 22, 2016

- 22.Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54(7):493–503 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dayton A. Improving quality of health care using the North Carolina Immunization Registry. N C Med J. 2014;75(3):198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013. IISAR data participation rates: 2013 ADOLESCENT participation table and map. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/annual-report-IISAR/2013-data.html#adolescent. Accessed October 9, 2015

- 25.Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, et al. ; Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):620–624 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]