Introduction

Alveolar hydatid disease (AHD) is caused by proliferative larval stage of the fox tapeworm, Echinococcus multilocularis.

AHD is confined to the northern hemisphere, i.e. Europe, Russia, China, Japan and North America. The total number of AE cases in the world is 18,235 per year with China accounting for 91% of cases.1 India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan border these endemic zones and may have a few cases. A few case reports are the only literature available about these cases, and incidence in India as calculated based on the case reports is one per year.2

Foxes and dogs are the definitive hosts and rodents are the intermediate hosts. Man gets infected accidentally and eggs develop into the metacestode stage in the liver, proliferate asexually, infiltrate to the peripheral parts of the liver and metastasize to other organs, hence this potentially fatal disease is also known as malignant hydatid disease.3

A rare case of alveolar hydatid disease of liver is being reported. We describe the clinical, radiological and pathological features to highlight the diagnostic difficulty encountered, and successful management of the case.

Case report

A 37-year-old male patient with no known co-morbidities presented with abdominal discomfort of one-year duration. Abdominal examination revealed a mass measuring 15 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm occupying right hypochondrium, epigastric region, and part of left hypochondrium. The surface was nodular with a sharp inferior margin. General and systemic examinations were unremarkable. LFT, routine biochemical and hematological investigations were within normal limits.

NCCT abdomen showed a space occupying lesion (SOL) involving Seg I–IV of liver, suggestive of atypical hemangioma.

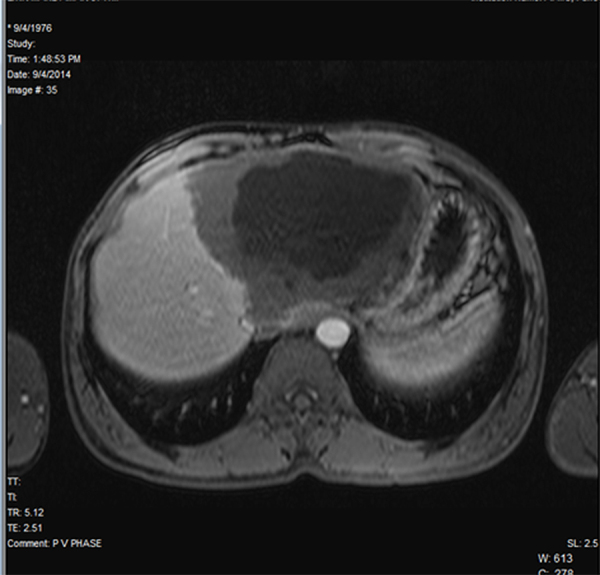

MRI revealed a large heterogeneous predominantly cystic mass lesion involving the entire left lobe and segments V and VIII of the right lobe of liver. The lesion was heterogeneously hypointense on T1WI and heterogeneously hyper intense on T2WI. The larger component of the lesion in the left lobe exhibited a thick (ranging from 1 to 2.5 cm) hypointense rim all around. Solid nature of the lesion in the right lobe showed multiple variable-sized cystic components interspersed within. The lesions did not contain fat, and they showed no restriction on diffusion or contrast enhancement on any of the phases on the dynamic contrast sequences (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Based on these findings, a differential diagnosis of Atypical hemangioma/Chronic Abscess/Atypical hydatid cyst was offered.

Fig. 4.

MRI: HASTE axial-cystic nature of larger component in the left lobe.

Fig. 5.

MRI: Postcontrast T1W axial – absent postcontrast enhancement.

Our patient belonged to Maharashtra and had no history of visit to the endemic zone.

Serology was positive for Echinococcus granulosus.

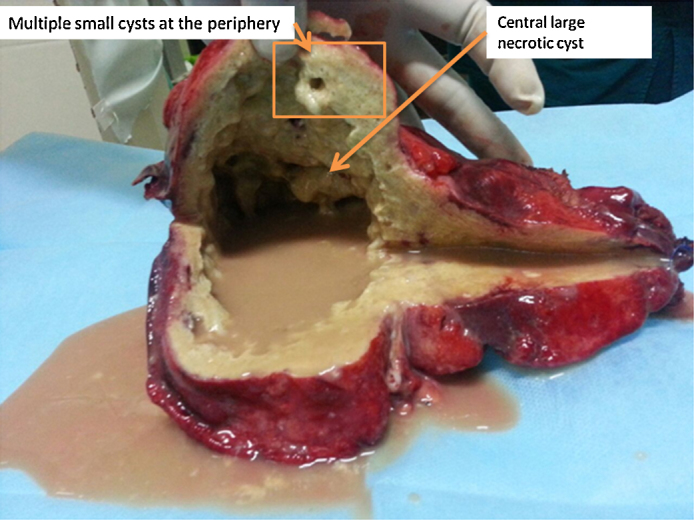

Exploratory laparotomy revealed Seg II, III, IV and part of Seg V replaced completely by a cyst, measuring 17 cm × 13 cm × 10 cm with a thick peripheral tissue. Extended left hepatectomy was done. Left hepatectomy specimen measured 24 cm × 20 cm × 4 cm. External surface appeared nodular. Cut surface showed a large cystic cavity with central necrotic area, measuring 16 cm × 12.5 cm with a peripheral rim of compressed liver parenchyma. The cyst wall was thick and contained 50 ml of thick purulent fluid. Surrounding area showed multiple small cysts with jelly like material within them (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gross specimen showing liver with a large central necrotic area with fluid and peripheral multiple cysts.

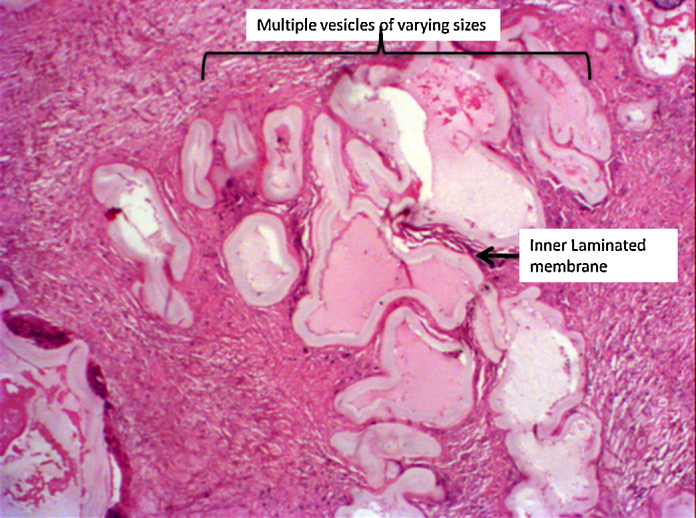

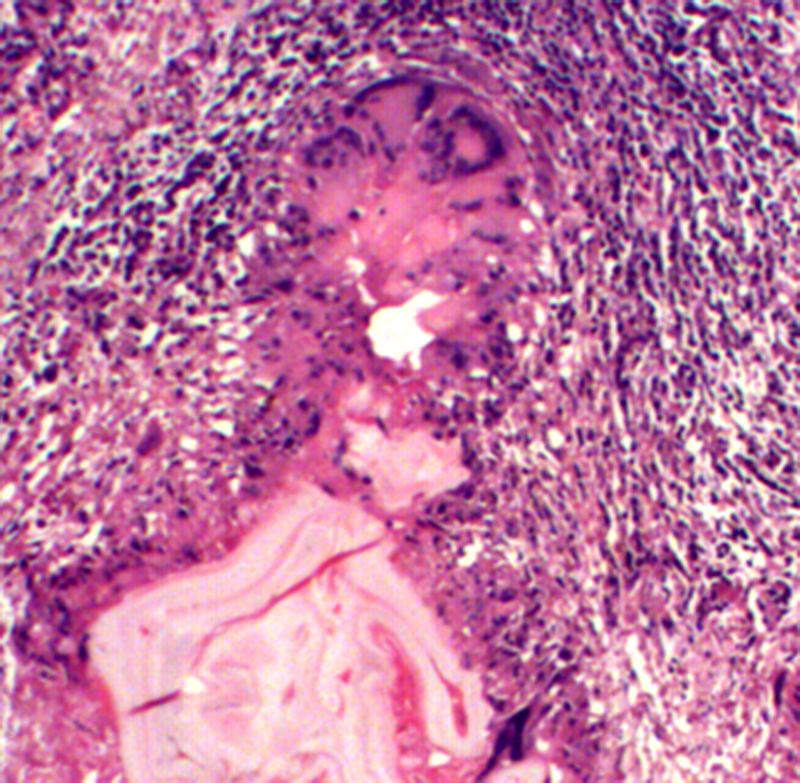

Microscopic examination revealed a central necrotic area. Multiple sections from the peripheral area showed multiple vesicles of varying sizes and shapes, infiltrating the liver parenchyma. The vesicles showed branching, both within and outwards, giving rise to an alveolar or multilocular appearance. Each cyst was lined by an inner illdefined germinal layer and an outer laminated acellular layer. Occasional hooklets were noted; however, scolices were not found. There was no pericyst. The cysts were seen infiltrating into the surrounding liver parenchyma, with foreign body granulomas, giant cells, and moderate amount of chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly of lymphocytes. Special stains PAS and ZN stain highlighted the characteristic laminated layer of the cyst. These morphological features were consistent with Alveolar Hydatid Disease (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph (20× H&E), multiple branching hydatid cysts seen infiltrating the liver parenchyma.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph (40× H&E) granulomatous reaction at the infiltrating margin of the cysts surrounding the cysts.

Postoperatively, the patient was started on Albendazole at the dose 10–15 mg/kg per day in two divided doses. His postoperative period was uneventful. He is presently asymptomatic and is being followed up regularly.

Discussion

Alveolar hydatid of the liver was first described by Virchow. He described the clinical features, detailed histopathology, and the specific infiltrative aspect of AE.4

Four species of Echinococcus produce infection; E. granulosus and E. multilocularis are the most common, causing cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE), respectively. Echinococcus vogeli and Echinococcus oligarthrus, cause polycystic echinococcosis but have only rarely been associated with human infection.1

AHD results from infection by the larval forms of E. multilocularis. Humans are accidental, intermediate hosts, infected either by direct contact with the definitive host or indirectly through contamination of food or water with parasite eggs.

After ingestion, the parasites reach the liver through lymphatics and portal system. The echinococcal metacestodes develop in the liver and form an alveolar structure, made up by several vesicles surrounded by large granulomas. Diameter of vesicles varies from less than 1 mm up to 15–20 cm. Brood capsules or protoscolices are rarely seen.4 We did not see any protoscolices or brood capsules in our case. Lesions may be complicated by central necrosis producing a cavity or pseudocyst4 as was seen in our case.

The budding daughter vesicles on the outer side form a progressive, infiltrating tumor-like growth. Over a period a large and heterogeneous parasitic mass is finally formed which consists of peripheral, actively proliferating sites, and centrally located necrotic tissue.

These cysts can be differentiated microscopically from cysts of E. granulosus, which are unilocular, have three layers, and do not exhibit a granulomatous reaction. Scolices and hooklets are easily found in CE, whereas rarely found in AE. The margins are not infiltrative. In contrast, E. multilocularis lacks the ectocyst and larval structures infiltrates into the host tissue causing destruction. This pattern mimics invasive carcinoma.5

Central necrotic cavities are often found in advanced stages of hepatic alveolar echinococcosis.6

Because of the slow growth, patients become symptomatic in later stages. Some patients present with mass lesions liver, abscess and jaundice and life threatening complications such as biliary cirrhosis, cholangitis and portal hypertension. These cysts have a tendency to recur. The release of metacestode vesicles into the blood or lymphatic vessels leads to metastases to organs like lung, brain, bone, etc.1 Untreated, the disease is eventually fatal.

Ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with standard and diffusion-weighted sequences, all are useful and complementary to each other and help in arriving at the right diagnosis.

AE is known to have varied imaging appearances. Mecit et al. have described five variants of the imaging appearances of AE. Type I to type V. Type I consists of multiple small cysts with no associated solid component. Type II has solid component with multiple small cysts. Type III has solid component with multiple irregular large cysts. Type IV lesions are solid without any cystic component and type V is described as a single large cyst.7

The lesion in our case was large, involving both lobes and exhibited mixed features following type II, IV as well as V in different locations and did not fall in one specific type. The major component in the left lobe of liver rather had a “mass like” appearance, which may also be confused with an abscess, which has not been described in any of these aforementioned five variants.

The case was referred from a peripheral hospital to a tertiary care center. The peripheral hospital had only the facility of CT hence that was the cross sectional imaging offered at that center. Otherwise also, CT scan is the primary modality offered followed by MRI whenever diagnostic dilemma arises, which was present in this case. In AHD, MRI scores over CT as far as the depiction of its multivesicular nature and vascular, biliary or extrahepatic extension is concerned.

On ultrasound, alveolar hydatid manifests as a large space occupying lesion with alternating areas of increased and decreased echogenicity. The margins are irregular with scattered foci of calcification. It also may show multiple hyperechoic nodules giving a “hailstorm” appearance.7 CECT confirms the morphology of the lesion and can confirm or exclude presence of calcifications.

The various differential diagnoses that can be considered are simple hepatic cyst, cystadenocarcinomas, cholangiocarcinoma, abscess, atypical hemangiomas and CE.

Immunodiagnostic methods are useful to narrow down the differentials of the imaging diagnosis. IgG ELISA has a sensitivity of 80–99% and specificity of 61.7% and frequently crossreacts with cestodes (89%), nematodes (39%), and trematodes (30%) and was therefore positive in this case.1

Recombinant (r) Em18 is also being evaluated to differentiate between alveolar hydatid and cystic hydatid.1

Radical surgery is the only option in operable cases. It should be followed by chemotherapy for at least 2 years. Inoperable cases and patients who have undergone nonradical resection or liver transplantation require continuous chemotherapy for many years. Patients should be monitored for at least 10 years, as there is a risk of recurrence. In contrast, surgery provides complete cure in CE.

In conclusion, AHD of liver is rare among Indian population and is a great mimicer. A high degree of suspicion complemented by the various diagnostic modalities can help in arriving at the right diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Nunnari G., Pinzone M.R., Gruttadauria S. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(13):1448–1458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i13.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torgerson P.R., Keller K., Magnotta M., Ragland N. The global burden of alveolar echinococcosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(6):722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vijay K., Vijayvergia V., Saha A., Naidu C.S., Rao P., Godara R. Hepatic alveolar hydatidosis – a malignant masquerade. Hell J Surg. 2013;85(2):135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis T., Matthias F. Rudolf Virchow and the recognition of alveolar echinococcosis, 1850s. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(5):732–735. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.070216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khuroo M.S., Datta D.V., Khoshy A., Mitra S.K., Chhuttani P.N. Alveolar hydatid disease of the liver with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1980;56(653):197–201. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.56.653.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottstein B. Molecular and immunological diagnosis of echinococcosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:248–261. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantarci M., Bayraktutan U., Karabulut N. Alveolar echinococcosis: spectrum of findings at cross-sectional imaging. RadioGraphics. 2012;32:2053–2070. doi: 10.1148/rg.327125708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]