Introduction

Iatrogenic causes such as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric tube insertion, caustic injury, and surgery are commonest causes of transmural esophageal perforation; less common iatrogenic causes include difficult endotracheal intubation, palliative intubation and noninvasive ventilation,1 and preparation for colonoscopy.2 When the transmural perforation occurs following forceful vomiting, it has been termed as spontaneous perforation also known as Boerhaave's syndrome.3 We report a case of spontaneous rupture of esophagus in an individual while having his meals.

Case report

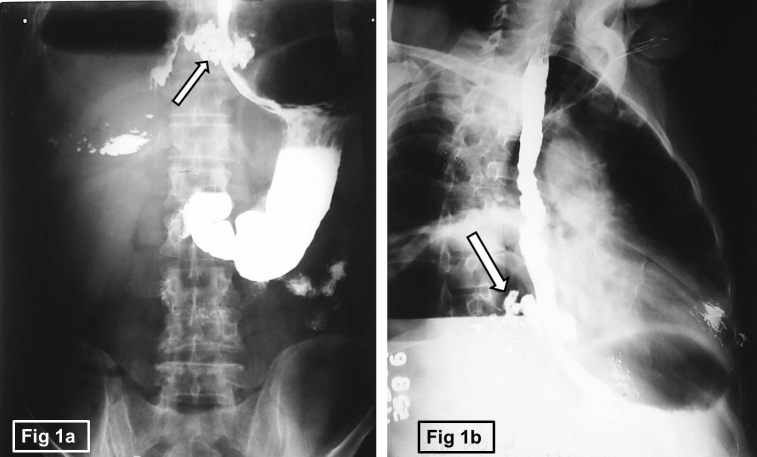

A 57-year-old male patient presented with history of sudden onset of severe right-sided chest pain after a bout of retching while having meal of meat and rice in dinner. This was followed by vomiting and difficulty in swallowing. He reported to a nearby hospital the same day where the treating physician requested for a barium swallow study. The barium swallow study revealed perforation in the distal esophagus with extravasation of barium in the surrounding mediastinum (Fig. 1a and b) and large air fluid level in the right lower chest/upper abdomen (Fig. 2). He was then transferred to a zonal hospital next day for further management. On examination, patient was anxious and sick. He was febrile and had tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension. Abdomen was soft with tenderness in the right upper quadrant. Chest examination revealed reduced air entry on right lower chest.

Fig. 1.

(a and b) The frontal view and Right anterior oblique of Barium swallow showing perforation in the lower third of the esophagus (white arrow) with extravasation of barium in surrounding mediastinum.

Fig. 2.

Erect radiograph chest and upper abdomen showing large air fluid level in the right lower chest and upper abdomen with well-defined superior wall suggesting a subpulmonic hydropneumothorax (white arrow).

Laboratory investigations revealed raised total leukocyte count (12,900/Cu mm), serum bilirubin (3 mg%), blood urea (45 mg%), and serum creatinine (1.2 mg%), clinical and lab findings were suggestive of sepsis. His CECT chest and upper abdomen were done for further evaluation, which revealed a transverse tear in lower third of esophagus communicating with the right pleural space (Fig. 3). Patient was initially managed conservatively with ionotropes and fluids, broad spectrum antibiotics, and intercostal drainage tube for 2 days. After stabilization, patient was air evacuated to tertiary care hospital, where he was managed surgically with right thoracotomy approach with primary repair of the perforation, which was buttressed with intercostal muscle flap, and a feeding jejunostomy was also performed. The patient had an uneventful post-operative recovery.

Fig. 3.

CECT chest showing transverse tear in lower third of esophagus (white arrow) communicating with the right pleural cavity.

Discussion

Dr Hermann Boerhaave was the first to describe a case of esophageal perforation in 1724.4 Autopsy of his patient Baron von Wassenaer, the Grand Admiral of Holland revealed a transverse esophageal tear in distal part with pleural cavity filled with gastric contents, who had died after an induced vomiting following a large meal.

The postulated hypothesis for esophageal rupture in Boerhaave's syndrome is abrupt increase in intraluminal pressure formed during vomiting due to failure in relaxation of cricopharyngeus muscle.5 It has also been reported to occur following straining in childbirth, weight lifting, bouts of coughing or hiccuping, blunt trauma, seizures, and forceful swallowing. The tear is commonly located in the distal esophagus and involves the left posterolateral wall roughly 2–3 cm above the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. The esophageal perforation in our case was in the posterolateral wall of esophagus 2 cm proximal to GE junction but on the right side.

The patient presents classically with repeated bouts of retching and vomiting, with too much food and alcohol intake involving a middle-aged man.6 Intolerable chest pain in lower chest and upper abdomen occurs after this and is associated with dyspnea due to sudden pleural effusion as was seen in this case. The classic acute presentation of retching or vomiting, lower chest pain, and surgical emphysema is defined as Mackler's triad and is seen in only 14% of patients.7

In the later stages patient may present with clinical features of infection and sepsis, which may manifest as fever, hypotension, and altered level of consciousness. This case had complications of esophageal rupture as was evident from the laboratory investigations and clinical examination.

Differential diagnosis of Boerhaave's syndrome is Mallory-Weiss syndrome, which is a mucosal tear of esophagus and does not include the tear of the smooth muscles of the esophagus. It generally occurs with vomiting and presents commonly with hematemesis. However, hematemesis, though may be occasionally present in Boerhaave's syndrome, is not its predominant feature.

Diagnosing Boerhaave's syndrome is not difficult given the history and its clinical presentation, the role of Radiology is not only in confirming the diagnosis by demonstrating the tear but also in evaluating the patients for its complications. Erect Radiograph chest posteroanterior view is the most useful in early diagnosis, as most of the patients will reveal an abnormal chest finding after the perforation.8 The V-sign of Naclerio may be seen on chest radiograph as radiolucent streaks of air seen in the retrocardiac region in the shape of the letter V. However, the most common finding is a one-sided pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax, other features such as pneumomediastinum or surgical emphysema may also be seen.

Any suspected patient of an esophageal perforation a contrast esophagogram should be done. The contrast agents of choice are ionic or non-ionic iodinated contrast agents such as gastrograffin or iohexol. The study will show leakage of contrast into the pleural cavity and/or mediastinum. The use of barium in these patients may lead to mediastinitis. However, a thin barium study can be done if the study by ionic and non-ionic contrast agents is negative and there is high index of suspicion of perforation, as barium can detect smaller leaks, which may be missed on gastrograffin study. In this case, the barium was used inadvertently in the peripheral hospital, as probably spontaneous rupture of esophagus was not suspected clinically.

CECT chest with oral water-soluble iodinated contrast will help in localizing the site of esophageal perforation (Fig. 3). If it does not identify the site of tear, it will reveal indirect evidence of esophageal perforation such as medastinal air or fluid, pleural effusion, and hydropneumothorax.9

Aim of management of a case of esophageal perforation should be to resuscitate the patient with adequate volume of fluid by intravenous route, broad spectrum antibiotics should be given to prevent secondary infection followed by timely surgical repair of the tear.10

The mortality rate in esophageal perforation is 10% with early diagnosis and can be as high as 50% if diagnosed late.6 The cause of late mortality is the associated complications such as mediastinal, pericardial and lung infection leading to sepsis.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency; therefore, a very high index of clinical suspicion should be kept in individuals presenting with classical history and Mackler's triad. Early identification of the perforation is crucial for patients’ favorable outcome and surgical intervention should be considered. Surgery to close the perforation is the management of choice, but medical management can be attempted depending on the general condition of the patient. Recently, there have been advancements in endoscopic/interventional radiology management of esophageal perforation; these include a powerful nitinol over-the-scope clipping system (OTSC system), esophageal stent insertion, endoscopic sealants, and endoscopic insertion of strips of Surgisis, which is an acellular matrix obtained from porcine submucosa. These interventional therapies have provided alternative management strategies to the conventional surgical management.11

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Col Atul Gupta (Retd), for the surgical management of the case at the zonal hospital.

References

- 1.Van de Louw A., Brocas E., Boiteau R., Perrin-Gachadoat D., Tenaillon A. Esophageal perforation associated with noninvasive ventilation: a case report. Chest. 2002;122(5):1857–1858. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.5.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu J.Y., Kim S.K., Jang E.C., Yeom J.O., Kim S.Y., Cho Y.S. Boerhaave's syndrome during bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol in a patient with postpolypectomy bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5(5):270–272. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duehring G.L. Boerhaave syndrome. Radiol Technol. 2000;72(1):51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams B.D., Sebastian B.M., Carter J. Honoring the Admiral: Boerhaave-van Wassenaer's syndrome. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(3):146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerke H.S. Boerhaave's syndrome and barogenic injuries of the esophagus. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1994;4(4):819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klin B., Berlatzky Y., Uretzky G. Boerhaave's syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Isr J Med Sci. 1989;25(2):113–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo K.M., Schneider J.I. High-risk chief complaints: chest pain – the big three. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27(4):685–712. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han S.Y., McElvein R.B., Aldrete J.S. Perforation of the esophagus: correlation of site and cause with plain film. Am J Roentgenol. 1983;145:537–540. doi: 10.2214/ajr.145.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker C.L., LoCiciero J., Hartz R.S., Donaldson J.S., Shields T. Computed tomography in patients with esophageal perforation. Chest. 1990;98:1078–1080. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White R.K., Morris D.M. Diagnosis and management of esophageal perforations. Am Surg. 1992;58(2):112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costamagna G., Marchese M. Management of esophageal perforation after therapeutic endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2010;6(6):391–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]