Introduction

Envenomation by bee sting is a common occurrence with self-limiting local reactions in most cases. Occasionally, anaphylaxis and systemic manifestations such as vasculitis, serum sickness, neuritis, and encephalitis have been reported.1 Rarely, Acute coronary syndrome may occur after an insect sting and is known as Kounis syndrome.2 We report and discuss a case of 46-year-old male patient who had a ST-elevation anterior wall myocardial infarction (MI) following multiple bee stings.

Case report

46-year-old male was stung by 8–10 bees over neck and face. Following this, he developed pain and itching over the bee sting sites. Fifteen minutes later, he developed severe, retro-sternal chest pain, associated with profuse sweating and difficulty in breathing. There was no history of syncope. He was taken to a military first aid center, where he was noted to have a normal pulse (86/min), blood pressure (124/82 mmHg), and respiration (14/min). There were multiple bee sting marks, and a mild erythematous rash and swelling of the face and lips. There was no respiratory distress. He was treated with injection chlorphenarmine maleate (10 mg IV), hydrocortisone (100 mg IV) and oral acetaminophen (650 mg PO) for his local symptoms. After a few hours of detention he felt better with minimal chest pain and was sent back to the barracks to rest. However, the next day he reported sick again for continuing mild retrosternal discomfort. On re-evaluation, swelling of the face and lips had marginally increased from the previous day. His pulse (86/min), blood pressure (110/76 mmHg), respiratory rate (20/min), temperature (98.8 °F), and systemic examination were normal. However, the ECG showed ST-elevation in the anterior wall leads (Fig. 1) with associated significant elevation of cardiac enzymes (Troponin T 4 ng/ml, CKMB 300 U/L). The hematological and biochemical parameters were normal. In view of persistent chest pain, ECG changes of ST elevation, and raised cardiac enzymes, he was thrombolyzed with Inj Tenecteplase (40 mg IV bolus). Post-thrombolysis, there was resolution of the chest discomfort and ECG changes (Fig. 2). A 2-D echocardiography showed moderate left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF 40%) with severe hypokinesia of anterior, anterolateral and inferior region of apex. Post-thrombolysis, he was managed with low molecular weight heparin, dual antiplatelets, statins, ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers. The coronary angiogram (CAG) done for risk stratification 13 days after the onset of chest pain showed a right dominant coronary circulation with patent epicardial coronaries.

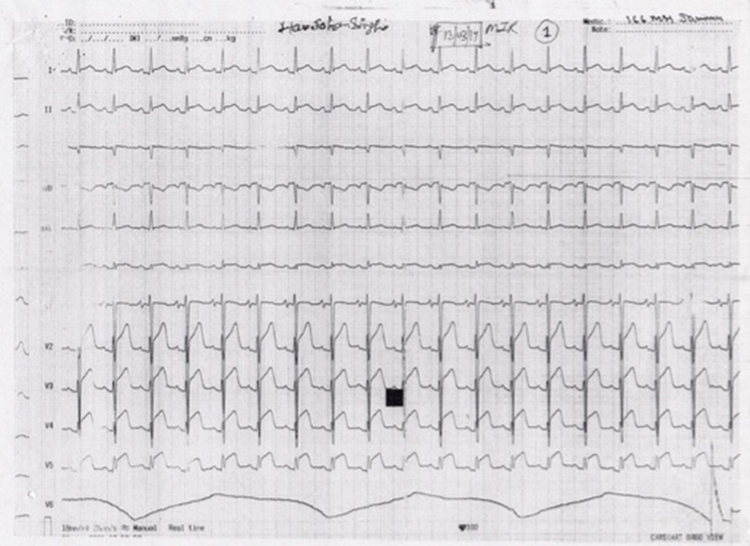

Fig. 1.

ECG (pre-thrombolysis) showing ST-segment elevation in the anterior wall leads.

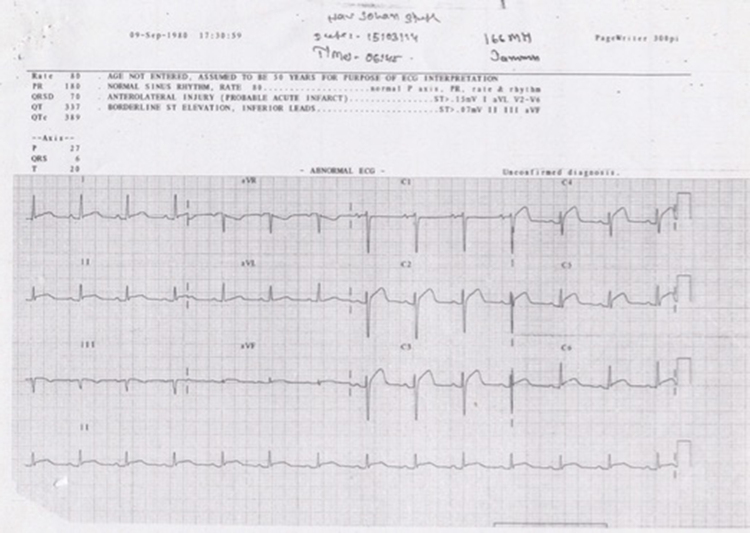

Fig. 2.

ECG (post-thrombolysis) showing resolution of the ST-segment elevation in the anterior wall leads.

Three months after discharge, he was well and ambulant for all activities of daily living. The echocardiography revealed mild left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF 50%) with regional dysfunction in the LAD territory. A 99mTc stress myocardial perfusion imaging (Fig. 3) also showed mild left ventricular dysfunction with a fixed perfusion defect of anterior, anterolateral and inferior region of the apex with no area of reversibility.

Fig. 3.

99mTc stress myocardial perfusion imaging showing a fixed perfusion defect of the anterior, anterolateral and inferior region of the apex with no areas of reversibility.

We were unable to do an intradermal skin test for bee venom and serum tryptase levels due to the lack of this facility at our hospital.

Discussion

Bees, wasps, ants, and sawflies belong to the hymenoptera order of insects. Stings and bites by these insects are common with a myriad of local and systemic reactions.1, 2 Of the various varieties of honey bees, the Africanized honey bee (Apismellifera scutellata) is the most common subspecies implicated. Though uncommon, the systemic manifestations include anaphylaxis, dyspnea, bronchospasm, generalized edema, vasculitis, acute renal failure, neuritis, encephalitis, and serum sickness.3 Acute coronary syndrome after hymenoptera stings is rare and seldom reported.3

In 1991, Kounis et al. described the syndrome of allergic angina3 as the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome with conditions associated with mast cell activation including allergic or hypersensitivity and anaphylactic or anaphylactoid insults due to allergic hypersensitivity reactions. Numerous causes such as hymenoptera sting, viper venom, food allergy, idiopathic anaphylaxis, mastocytosis, and serum sickness, and drugs such as NSAIDS, contrast media, antibiotics, and antineoplastic drugs capable of causing Kounis syndrome have been documented.3 This immune mediated injury is postulated to be triggered by mast cell activation and degranulation induced by IgE or non-IgE mechanism. The release of vasoactive inflammatory mediators such as histamine, serotonin, neutral proteases, arachidonic acid metabolites (thromboxane and leukotrines), and various cytokines and chemokines cause vasospasm, platelet and clotting factor activation. This results in coronary vasospasm and thrombosis causing myocardial ischemia and infarction. Besides Kounis syndrome, anaphylaxis causing severe hypotension may result in decreased myocardial perfusion. Vasospasm secondary to use of exogenous adrenaline in anaphylaxis may cause undue vasoconstriction resulting in myocardial injury. Rarely, direct myocardial necrotizing effect of large amounts of venom released during multiple bee stings has also been postulated as a cause of myocardial damage.2, 4, 5

Two variants of Kounis syndrome have been described.4 Type I variant includes normal coronary arteries without predisposing factors for coronary artery disease and Type II variant includes patients with culprit but quiescent pre-existing atheromatous disease, in whom acute allergic episode could induce plaque erosion or rupture manifesting as an acute MI. In our patient, Type I Kounis syndrome was more likely the cause of the ST-elevation MI. However, as thrombolysis was done prior to the CAG, it cannot be ascertained whether the infarction was due to vasospasm alone or if there was an associated thrombus formation with or without a plaque rupture. As the CAG showed patent epicardial coronaries, it is likely that vasospasm was the primary mode, with superadded thrombosis. Moreover, the absence of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia and hyperhomocysteinemia makes vulnerable atherosclerotic vessel disease less likely. Anaphylaxis causing severe hypotension resulting in decreased myocardial perfusion is also unlikely as immediately after the sting, and on repeated examination, there was no hypotension. Considering that only 10–15 bees stung our patient, it is unlikely that the cumulative dose was high enough for direct myocardial necrotizing damage. Also, this method of affection is likely to give global myocardial dysfunction rather than a vessel specific regional wall involvement.

The right coronary artery has been found to be more commonly involved due to the presence of an ostial muscular band, which is vulnerable to spasm. However, our patient had electrocardiographic features to suggest left anterior descending artery affection, which has been rarely reported in literature.6, 7, 8

The clinical presentation of an acute coronary syndrome may be quite varied, ranging from being completely silent, to a delayed presentation several hours after of the sting.2, 9, 10 The key to early diagnosis and management lies in a high index of clinical suspicion of this rare occurrence. The delay in diagnosis of AMI in our case was due to lack of awareness. It is recommended that every patient, who complains of chest pain after a bee sting, should undergo serial ECG recordings, regardless of the severity of the patients reaction to the bee sting.6, 9, 10

Conclusion

Kounis syndrome is a rare cause of an acute coronary syndrome with atypical presentations. This along with the lack of knowledge of this entity may lead to delay in diagnosis and treatment. The present case highlights the importance of suspicion and early recognition of this rare syndrome.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Freeman T.M. Hypersensitivity to hymenoptera stings. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1978–1984. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nittner-Marszalska M., Kopeć A., Biegus M. Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction after multiple bee stings. A case of “delayed” Kounis syndrome? Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:e62–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kounis N.G., Zavas G.M. Histamine induced coronary artery spasm: the concept of allergic angina. Br J Clin Pract. 1991;45:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kounis N.G. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction): a natural paradigm? Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira D.B., Costa R.S., De Oliveira J.A., Muccillo G. An infarct-like myocardial lesion experimentally induced in Wistar rats with Africanized bee venom. J Pathol. 1995;177(1):95–102. doi: 10.1002/path.1711770114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biteker M. Current understanding of Kounis syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:777–788. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukta V., Chandragiri S., Das A.K. Allergic myocardial infarction. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(2):157–158. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.107544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puvanalingam A., Karpagam P., Sundar C., Venkatesan S., Ragunanthanan Myocardial infarction following bee sting. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62(August):78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erbilen E., Gucan E., Albayrak S., Ozveren O. Acute myocardial infarction due to a bee sting manifested with ST wave elevation after hospital admission. South Med J. 2008;101(4):448. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318167ba78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombardi A., Vandelli R., Cerè E., Di Pasquale G. Silent acute myocardial infarction following a wasp sting. Ital Heart J. 2003;4:638–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]