Abstract

Introduction

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare disease that accounts for <1% of breast cancer cases. The most common treatment is modified radical mastectomy (MRM). Recently, breast conservative surgery (BCS) is getting popular for MBC treatment. We report a case and reviewed the literature to investigate whether emerging BCS can be considered as an alternative of a more radical surgery.

Presentation of case

A 46 y.o. patient, presented with a painless left breast lump over a period of six months. The patient underwent a quadrantectomy at another institution. Pathology revealed an intraductal carcinoma in close proximity to the margins of excision. Adjuvant hormonal therapy was proposed to the patient, who refused and was referred to our Institution. We performed a MRM and a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). A contralateral breast liposuction and an adenectomy were also performed. The patient underwent also a nipple-areolar complex reconstruction. The patient didn’t receive adjuvant therapy.

Discussion

Both oncological safety and satisfactory cosmetic outcomes are the goals of MBC treatment. No specific guidelines for MBC treatment have been proposed. MRM is currently the surgical gold standard of MBC (approximately 70% of all cases). Some authors reported that male BCS associated with radiation therapy is a feasible alternative MRM. Taking into account data from the literature and considering the previous surgery, in the case we report, we offered a MRM, SLNB and a contralateral breast symmetrization.

Conclusion

MRM with SLNB and reconstruction of male breast asymmetry should be still considered as the treatment of choice of MBC.

Keywords: Male breast cancer, Breast conserving surgery, Mastectomy, Breast, Case report, Chest wall reconstruction

1. Introduction

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare disease that accounts for < 1% of all breast cancer cases and < 1% of all male cancers [1]. However, as female breast cancer (FBC), the incidence of MBC has increased over the past 25 years [2]. The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer is slightly older in men (67 y.o.) than in females (62 y.o.) [3]. The typical presentation of breast cancer onset in men is a unilateral painless palpable mass in a central sub-areolar location or eccentric to the nipple-areolar complex with early nipple involvement [4], [5]. According to literature data, most of male breast cancers are invasive ductal carcinoma (85–90%) [4], [6]. About 65–90% of MBC are estrogen and progesterone receptor positive, similarly to (FBC) breast cancer in menopausal women [7]. MBC causes a higher mortality than the female counterpart [6]. MBC patients have a worse survival rate compared to women, because of a more advanced disease and an older age at diagnosis [2], [4]. According to the literature on the treatment of MBC, modified radical mastectomy is generally preferred to breast conservation surgery (BCS) [8], [9]. Some others reported more radical surgical approach; 71% of patients in Sanguinetti paper treated with more radical treatment such as radical mastectomy (RM) [10].

However, as for FBC treatment, minimally invasive surgical procedures are getting increasingly popular for MBC treatment [8], [11]. According to Zaenger study, in the preliminary data collected from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 56% of MBC patients had stage T1 cancer, but only 4% had undergone breast conservation surgery [12]. We report a case of MBC treatment and we extensively reviewed pertinent literature of the last 10 years to investigate whether BCS can be considered as the gold standard treatment, or if a more radical surgery is preferable.

2. Presentation of case

A 46 y.o. caucasian patient, amateur swimmer, with no significant past medical history and no family history of breast cancer, presented with a painless left breast lump and nipple bloody discharge over a period of six months. Physical examination revealed a firm mass in the Upper Outer Quadrant (UOQ). Mammography and breast ultrasonography confirmed the presence of the neoplastic mass. No pathological lymph nodes were detected in the axilla at the clinical and ultrasound examination. Furthermore the patient shows a I grade gynecomastia [13]. The patient underwent a nipple sparing upper outer quadrantectomy with excision of the retro-areolar tissue to the left breast at another institution. (Fig. 1) Pathology revealed a low-grade intraductal carcinoma, clinging and micropapillary type, ER/PR+. The tumor was in close proximity to the margins of excision. The cancer TNM staging was IA (pT1,N0,MO) according to AJCC guidelines [14]. Adjuvant hormonal therapy was proposed to the patient. He refused a prolonged endocrine therapy and was referred to our Institution for an oncological and surgical advice.

Fig. 1.

Multistage surgical management of MBC. (a) Post conservative surgery appearance of the patient. (b) Four months after mastectomy and before NAC reconstruction. (c) Six months postoperative result.

On the basis of the pathology report and the relative residual paucity of breast tissue, we proposed to the patient a modified radical mastectomy as an alternative to adjuvant hormonal therapy. The patient accepted the suggested surgical treatment. A left modified radical mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy were performed, and associated with a contralateral breast liposuction and adenectomy, as indicated in a grade II gynecomastia [13] (Fig. 2). Four months later the patient underwent a left Nipple-Areolar complex (NAC) reconstruction under local anesthesia. Areolar reconstruction was performed using a full-thickness skin graft from the ipsilateral groin, while nipple reconstruction was achieved using a subdermal single pedicle local flap (Fig. 3). Histologic examination of the residual breast parenchyma revealed the persistence of sparse foci of intra-ductal carcinoma, clinging and micropapillary type, with tumor free margins, while the SLNB was negative for metastatic disease. Histological examination of contralateral breast was also negative. The patient did not receive any adjuvant therapy. He is currently under oncological follow-up according to the International guidelines established for FBC, and is free from at 18 months follow-up [14].

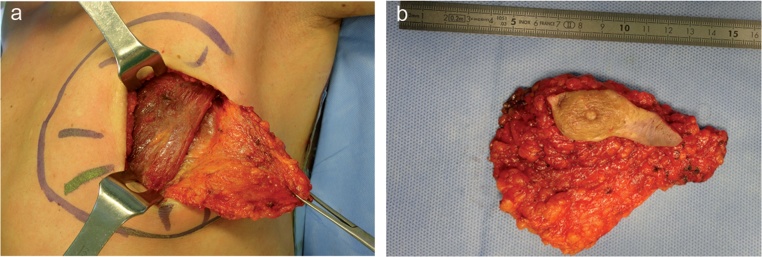

Fig. 2.

(a) Left modified radical mastectomy: the breast tissue is detached from the pectoralis major muscle. (b) Sample of the mastectomy.

Fig. 3.

Nipple-Areolar complex (NAC) reconstruction. Intraoperative view.

3. Discussion

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for FBC treatment and surveillance are well established, but no specific guidelines for male patients exists, and no clinical trials or prospective studies have been performed. In the absence of definite data, the treatment of MBC has traditionally followed guidelines established for FBC [1], [15], [16], [17], [18]. However, modified radical mastectomy is currently the surgical gold standard treatment of MBC (approximately 70% of all cases), followed by radical mastectomy (8–30%), total mastectomy (5–14%), and lumpectomy with or without irradiation (1–13%) [2], [19]. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, between 1983 and 2009, 4707 (86.8%) MBC patients underwent mastectomy while 718 (13.2%) underwent breast conservation surgery (i.e., lumpectomy) [16], [18]. Although breast conservation surgery (BCS) has not known the same widespread acceptance as in FBC patients, BCS is getting popular also for MBC treatment [11]. Nowadays, lumpectomy is performed in a small but rising proportion of MBC patients; as reported by the SEER database, the rate of patients undergoing lumpectomy between 2007 and 2009 is significantly superior to the corresponding rate between 1983 and 1986 (15.1% vs. 10.6%). Some authors reported that breast conservation surgery associated with radiation therapy, in selected patients, is a feasible alternative to total or modified radical mastectomies [8], [11], [16], [21]. The literature review showed that male patients reported to have conservative surgery were likely to be of black race and elderly; they did not receive lymph node sampling, had advanced stage disease, and were often treated with palliative purposes [1], [4], [8].

Conservative surgery has the disadvantage of requiring adjuvant radiation therapy and, in selected patients, hormonal therapy to reach the same safety of mastectomy. Radiation therapy involves quite a few sequelae and men are usually more reluctant than women to receive it [1]. According to the SEER data, just the 35% of patients treated with lumpectomy also received radiation therapy, while the others (75%) received surgery alone [16], [18]. This data reveal that men undergoing breast conservation surgery may receive a suboptimal treatment, not safe as mastectomy and with a higher recurrence rate. Physical and emotive consequences of hormonal therapies and chemotherapies, including the fear for an emasculating therapy and sexual dysfunction, are more problematic than in the female counterpart, which limits their indications in male patients. As said by the recent literature [8], [11], [12], [16], [17] emerging BCS, in early stage MBC, has comparable survival rates to MRM and has been progressively more performed in the last years. Despite the current transition from radical to conservative surgical treatment of MBC, we retain that MRM is still regarded as the standard treatment due to the paucity of male breast tissue, the typical central sub-areolar location of the cancer with early nipple involvement and the debilitating side effects of adjuvant therapy necessary in BCS. Moreover scarring and chest wall deformity resulting from the male mastectomy are less disfiguring than in female patients. Taking into account literature data and considering tumor histology and the pathologic close margins of the previous surgery, in the case we report, we offered a modified radical mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. The patient agreed with the proposed treatment, preferring to receive a radical surgery, rather than an adjuvant treatment [20].

Also, we decided for a comprehensive cosmetic treatment and reshaping of the entire chest wall, achieved through NAC reconstruction and contralateral symmetrization (Fig. 1).

MBC involves patients between the fifth and sixth decades of life, when a moderate grade of gynecomastia is physiological [17]. In our patient the breast symmetry was achieved performing a contralateral liposuction and adenectomy instead of the volume replacing of the mastectomy side [6]. This approach let to perform a prophylactic adenectomy in patients with an additional risk of contralateral cancer. The contralateral breast treatment has both oncological and aesthetic purposes.

The patient was satisfied with the cosmetic outcome and went back to his recreational activities, starting again to swim, with no shame or concern to show his chest. Men who undergo mastectomies usually complain unsatisfactory aesthetic results because of the excision of the NAC and the alteration of the normal male chest contour [21]. Thus, post-oncological male chest reshaping should be regularly considered in men, in order to reduce postoperative psychological distress by restoring the patient’s body image.

4. Conclusion

Male breast cancer should be treated as a rare and unique disease, rather than just as a hormone-positive cancer that mainly affects postmenopausal women [1], [9] Based on the physical and psychological factors related to the male sex as well as on oncological considerations, we believe that modified radical mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or axillary dissection and reconstruction of male breast asymmetry should be considered as the treatment of choice of MBC, as this radical and comprehensive treatment guarantees both an optimal oncologic care and cosmetic result.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

All authors have no source of funding.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Guarantor

Adriana Cordova, Gabriele Giunta.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request

SCARE criteria

The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [22].

References

- 1.Cloyd J.M., Hernandez-Boussard T., Wapnir I.L. Poor compliance with breast cancer treatment guidelines in men undergoing breast-conserving surgery. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;139(1):177–182. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2517-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa B., Moser E., Cardoso F. An update on male breast cancer and future directions for research and treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;717(1–3):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottini L., Palli D., Rizzo S. Male breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2010;73(2):141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fentiman I.S., Fourquet A., Hortobagyi G.N. Male breast cancer. Lancet. 2006;367(9510):595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan T.J., Leong L.C., Sim L.S. Clinics in diagnostic imaging (147). Male breast carcinoma. Singapore Med. J. 2013;54(6):347–352. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patten D.K., Sharifi L.K., Fazel M. New approaches in the management of male breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2013;13(5):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansen Taber K.A., Morisy L.R., Osbahr A.J. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis, and management (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2010;24(5):1115–1120. doi: 10.3892/or_00000962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fogh S., Kachnic L.A., Goldberg S.I. Localized therapy for male breast cancer: functional advantages with comparable outcomes using breast conservation. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2013;13(5):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korde L.A., Zujewski J.A., Kamin L. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(12):2114–2122. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanguinetti A., Polistena A., Lucchini R., Monacelli M., Galasse S., Avenia S. Male breast cancer, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment: Twenty years of experience in our Breast Unit. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016;20S:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golshan M., Rusby J., Dominguez F., Smith B.L. Breast conservation for male breast carcinoma. Breast. 2007;16(6):653–656. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaenger D., Rabatic B.M., Dasher B., Mourad W.F. Is Breast conserving therapy a safe modality for early-Stage male Breast cancer? Clin. Breast Cancer. 2016;16(April (2)):101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordova A., Moschella F. Algorithm for clinical evaluation and surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008;61(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Breast Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0051. http:/www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp Available at: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiluk J.V., Lee M.C., Park C.K. Male breast cancer: management and follow-up recommendations. Breast J. 2011;17(5):503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloyd J.M., Hernandez-Boussard T., Wapnir I.L. Outcomes of partial mastectomy in male breast cancer patients: analysis of SEER, 1983–2009. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20(5):1545–1550. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staruch Robert M.T., Rouhani Maral J., Ellabban Mohammed. The surgical management of male breast cancer: time for an easy access national reporting database? Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2016;9(August):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giordano S.H. Lumpectomy in male patients with breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20(8):2460–2461. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cutuli B. Strategies in treating male breast cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007;8(2):193–202. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruddy K.J., Giobbie-Hurder A., Giordano S.H. Quality of life and symptoms in male breast cancer survivors. Breast. 2013;22(2):197–199. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaverien M.V., Scott J.R., Doughty J.C. Male mastectomy: an oncoplastic solution to improve aesthetic appearance. J. Plast Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013;66(12):1777–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. (article in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]