Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the efficacy of quantitative fecal immunochemical test (FIT) as biomarker of disease activity in ulcerative colitis (UC).

METHODS

Between February 2013 and November 2014, a total of 82 FIT results, obtained in conjunction with colonoscopies, were retrospectivelyevaluated for 63 patients with UC. The efficacy of FIT for evaluation of disease activity was compared to colonoscopic findings. Quantitative fecal blood with automated equipment examined from collected feces. Endoscopic disease severity were assessed using the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) classification. The extent of disease were classified by proctitis (E1), left sided colitis (E2), and extensive colitis (E3). Clinical activity were subgrouped by remission or active.

RESULTS

All of 21 patients with MES 0 had negative FIT (< 7 ng/mL), but 22 patients with MES 2 or 3 had a mean FIT of > 134.89 ng/mL. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of negative FIT about mucosal healing were 73.33%, 81.82%, 91.49%, 51.43% and 73.17%, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of predictive value of positive FIT (cutoff value > 100 ng/mL) about active disease status were 45.45%, 93.33%, 71.43%, 82.35% and 26.83%, respectively. Among patients with clinical remission, FIT was negative in 31 (81.6%) of 38 cases, with a mean fecal hemoglobin concentration of 6.12 ng/mL (range, negative to 80.9 ng/mL) for this group of patients. Among patients with clinical active disease, FIT was negative in 16 (36.4%) out of 44 cases, with a mean fecal hemoglobin concentration > 167.4 ng/mL for this group of patients. FIT was positively correlated with endoscopic activity (r = 0.626, P < 0.01) and clinical activity (r = 0.496, P < 0.01). But, FIT did not correlate with the extent of disease (r = -0.047, P = 0.676)

CONCLUSION

Quantitative FIT can be a non-invasive and effective biomarker for evaluation of clinical and endoscopic activity in UC, but not predict the extent of disease.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Fecal immunochemical test, Mayo endoscopic subscore, Biomarker, Disease activity

Core tip: Until now, colonoscopy has been regarded as the gold standard to assess mucosal status and disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Recently, non-invasive markers of mucosal healing have been studied in UC. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is one of them suggested association with mucosa healing in some studies. Our results have identified that FIT correlated positively with endoscopic activity and clinical remission, but not with extent of disease. In particular a negative FIT could be regarded as an indication of endoscopic and clinical remission. FIT can be a non-invasive and economic biomarker in patients with UC.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the colorectum that is characterized by a clinical course of remission and relapse[1]. Assessment of the response to treatment and monitoring of disease activity are two important aspects of the clinical management inpatients with UC. Clinical indices do not always correlate with actual inflammation in UC patient and active mucosal inflammation is often present in asymptomatic patients. Therefore, recent opinions increasingly require to achieve both clinical response and endoscopic mucosal healing (MH) in the treatment of UC[2-4]. To date, the evaluation of mucosal inflammation with colonoscopy is the gold standard to assess disease activity in patients with UC. However, colonoscopic examination is difficult to frequently perform due to cost and inconvenience to patients. Therefore, identification of non-invasive biomarkers of disease activity in UC is a research priority.

Fecal calprotectin (FC) may provide a promising non-invasive marker of mucosal inflammation, with several studies having shown a correlation between FC and the severity of mucosal inflammation[5-9]. However, the measurement of FC requires the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique which usually can only be performed in tertiary healthcare institutions, usually takes several hours to perform and is expensive[6]. In contrast, quantitative fecal immunochemical test (FIT) measures hemoglobin concentration in feces by using an antibody for human hemoglobin. FIT has been used to screen for colorectal cancer in the general population[10]. FIT quantifies blood in fecal samples simply and rapidly using automated equipment[11]. In patients with UC who are in clinical remission, occult blood can be present in stool samples due to residual mucosal inflammation. In fact, previous studies have shown that FIT correlates well with the mucosal status in patients with UC[12,13].

In this study, we measured FITs in patients with UC who had undergone colonoscopy with the aim of comparing endoscopic disease activities with FITs. Furthermore, unlike other studies thus far, we used FIT to compare clinical disease activity and extent of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and diagnosis of UC

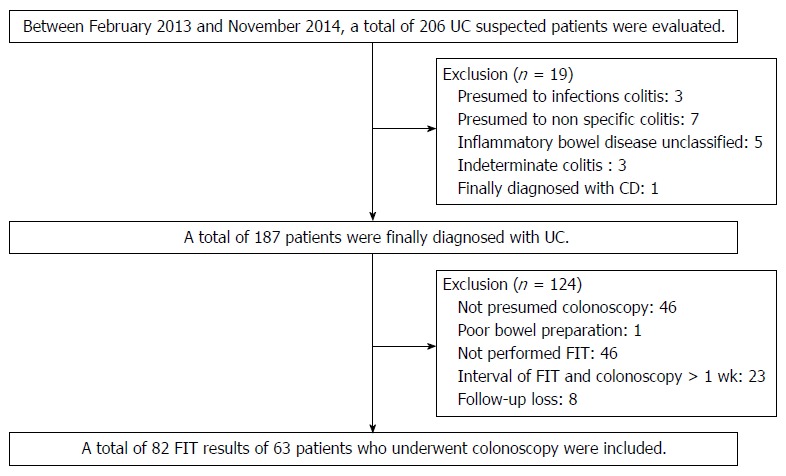

Between February 2013 and November 2014 we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with UCat the Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Korea. During the period, a total of 206 patients with suspected UC were evaluated. UC is diagnosed based on a comprehensive medical history and clinical features, in combination with typical endoscopic and biopsy findings according to current guidelines. UC is a chronic inflammatory condition causing continuous mucosal inflammation of the colon without granulomas on biopsy, affecting the rectum and a variable extent of the colon in continuity, which is characterized by relapsing and remitting course[14,15]. Patients are not clearly diagnosed with UC including inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU) and indeterminate colitis were excluded. IBDU is the cases where a definitive distinction between UCand Crohn’s disease (CD), or other cause of colitis cannot be made after the history, endoscopic appearances, histopathology and appropriate radiology[15]. Indeterminate colitis is a term which has overlapping features of UC and CD[16]. Rule out other diseases in this process, a total of 187 patients were diagnosed with UC. Patients not performed colonoscopy or FIT were excluded and patients with the interval of FIT and colonoscopy was more than 1 wk were also excluded. Finally a total of 82 FIT results of 63 patients who underwent colonoscopy included in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the enrolled patients. UC: Ulcerative colitis; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test.

Fecal sampling and FIT analysis

Fecal samples were prepared on the morning of hospital visit or the previous day hospital visit. FIT results were obtained on the day of colonoscopy (56/82, 68.3%) or within 1 wk (before or after) of colonoscopy (26/82, 31.7%). About seasonally correlation FIT results and disease activity or mucosa status in UC patients is not yet known. But one study reported that FIT results and disease activity of patients with UC can deviate for 2-4 wk[17]. With reference to the study, patients with more than 1 wk intervals between FIT and colonoscopy were excluded. Submitted stool samples were immediately processed and examined using the HM-JACK system (Kyowa Medex, Japan), a fully automated quantitative FIT system. The HM-JACK system can accurately measure fecal hemoglobin concentration within a range of 7-300000 ng/mL. Stools with a hemoglobin concentration > 1000 ng/mL were classified as bloody stools. On the other hand, fecal specimens with a hemoglobin concentration < 7 ng/mL were classified as negative (0-7 ng/mL). The HM-JACK system cannot accurately differentiate hemoglobin concentrations < 7 ng/mL.

Assessment of clinical and endoscopic activity

Clinical and endoscopic disease activity were evaluated using the Mayo scoring system for UC[18]. Endoscopic remission and MH were defined bya Mayo endoscopic score (MES) of “0” or “1”[3]. Clinical remission was defined by a Mayo stool frequency subscore of “0” or “1” and a Mayo rectal bleeding subscore of “0”[3]. Patients with any other Mayo scores were considered to be active disease state. The extent of UC was based on the Montreal Classification, with patients classified as having either: proctitis (E1), left sided colitis (E2) or extensive colitis (E3)[15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Spearman’s and Kendall’s tau rank correlation were performed to determine the association among FIT, MES, the extent of disease and clinical remission. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), with associated 95%CI, for detecting mucosal status based on FIT results, were determined. Statistical significance was set at a P value of 0.05.

RESULTS

Patients characteristics

A total of 82 FITs were evaluated for 63 patients with UC, 60 males and 22 females, with a median age of 47.9 years. Baseline characteristics of our patient group are shown in Table 1. Mean disease duration was 33.5 mo (range, 0-217 mo). All patients were treated with suppository or oral 5-ASA, with 46 patients (56.1%) treated with additional therapy: 17 patients (20.7%) with systemic steroids; 23 patients (28%) with azathioprine; and 6 patients (7.3%) with anti TNF-alpha therapy. During the study period, 3 patients were hospitalized for severe UC. No patient underwent surgery for UC-related complications and no patient died.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled cases

| Characteristics variables | Value |

| Age (yr), mean (range) ± SD | 47.9 (22-75) ± 12.5 |

| Male/Female, n (%) | 60/22 (73.2/26.8) |

| Disease duration (mo), mean (range) ± SD | 33.5 (0-217) ± 48.3 |

| MES, n (%) | |

| 0 | 21 (25.6) |

| 1 | 39 (47.6) |

| 2 | 15 (18.3) |

| 3 | 7 (8.5) |

| Disease extent, n (%) | |

| Extensive colitis | 32 (39.0) |

| Left sided colitis | 30 (36.6) |

| Proctitis | 20 (24.4) |

| Fecal hemoglobin concentrations (ng/mL), n (%) | |

| 0-7, negative | 47 (57.3) |

| 7-100 | 21 (25.6) |

| 100-1000 | 11 (13.4) |

| > 1000 | 3 (3.7) |

| Drug at study entry, n (%) | |

| Oral / Suppository 5-ASA | 64 (100.0)/18 (22.0) |

| Systemic steroids | 17 (20.7) |

| Azathioprine | 23 (28.0) |

| Anti-TNFα | 6 (7.3) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; 5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylic acids; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

Correlation between FIT and endoscopic finding

Colonoscopy was performed in all patients during the study period. Among the 82 colonoscopy, 38 (46.3%) were performed in patients in clinical remission and the other 44 (53.7%) in patients with clinical active disease. The distribution of MES based on colonoscopic findings was as follows: MES of “0” in 21 patients (25.6%); MES of “1” in 39 (47.6%); MES of “2” in 15 (18.3%) patients; and MES of “3” in 7 (8.5%). All of patients with MES of “0” had negative FIT (< 7 ng/mL). Patients with MES of “2” or “3” had a mean fecal hemoglobin concentration of 134.89 ng/mL (range, negative to > 1000 ng/mL). Among patients with MES of “2” or “3”, 18.2% (4 of 22 patients) had a negative FIT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Negative fecal immunochemical test probability (%) and mean fecal immunochemical test values according to mayo endoscopic subscore

| MES | Negative FIT (%) | mean FIT (ng/mL) |

| 0 | 21/21 (100) | 0 |

| 1 | 44/60 (73.3) | 33.94 |

| 2 or 3 | 4/22 (18.2) | > 134.891 |

Three cases in MES “2” or “3” were measured more than 1000 ng/mL fecal hemoglobin concentration. MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test.

The distribution of MES for the 47 negative FIT cases was as follows: MES of “0” in 21 patients (44.7%); MES of “1” in 22 (46.8%) patients; MES of “2” in 3 (6.4%) patients; and MES of “3” in 1 patient (2.1%). Therefore, a negative FIT identifies mucosa healing, assessed by endoscopy (MES of “0” or “1”), with a probability of 92%. For the 35 patients with a positive FIT, the distribution of MES was as follows: MES of “0” in 0 patient; MES of “1” in 17 patients (48.6%); MES of “2” in 12 patients (34.3%); and MES of “3” in 6 patients (17.1%). Among the three patients with FIT >1000 ng/mL, 2 patients had a MES of “2”, with the other patient having a MES of “3” (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mayo endoscopic subscore according to fecal immunochemical test values

| n (%) | |

| Negative FIT cases (n = 47) | |

| MES 0 or 1 | 43 (91.5) |

| MES 2 or 3 | 4 (8.5) |

| Positive FIT cases (n = 35) | |

| MES 0 | 0 |

| MES 1 | 17 (48.6) |

| MES 2 or 3 | 18 (51.4) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test.

When we consider only the 60 cases in whom endoscopy identified MH, FIT was negative in 44 of these 60 cases (73.33%). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of the fecal hemoglobin concentration in relation to MH are reported in Table 4 and summarized as follows: sensitivity, 73.33%; specificity, 81.82%; PPV, 91.49%; NPV, 51.43%; and accuracy, 73.17%. The change in these predictive values of FIT using a cutoff value of fecal hemoglobin concentration > 100 ng/mL, which is popularly used for colon cancer screening, is reported in Table 5. The predictive value of FIT specifically in patients with an active disease status, identified by endoscopy, is summarized as follows: sensitivity, 45.45%; specificity, 93.33%; PPV, 71.43%; NPV, 82.35%; and accuracy, 26.83%.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of fecal immunochemical test for mucosal healing (mayo endoscopic subscore 0 or 1)

| Negative FIT (< 7 ng/mL) | |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 0.73 (0.60-0.83) |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 0.81 (0.59-0.94) |

| PPV (95%CI) | 0.91 (0.80-0.97) |

| NPV (95%CI) | 0.52 (0.35-0.70) |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 0.73 (0.62-0.82) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value.

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of fecal immunochemical test for endoscopic active disease (mayo endoscopic subscore 2 or 3)

| Positive FIT (> 100 ng/mL) | |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 0.45 (0.24-0.67) |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 0.93 (0.83-0.98) |

| PPV (95%CI) | 0.71 (0.41-0.91) |

| NPV (95%CI) | 0.82 (0.71-0.90) |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 0.26 (0.17-0.37) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value.

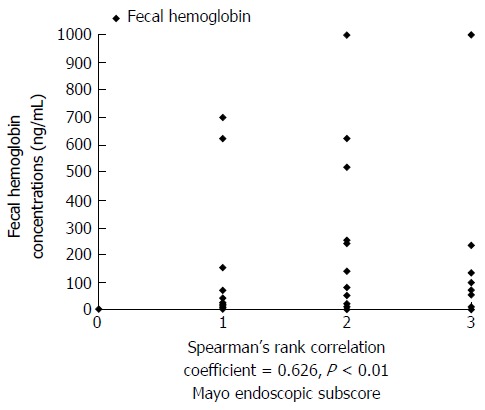

As a result, FIT was positively correlated with endoscopic activity, with a Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient of 0.626 and corresponding P value <0.01. The correlation between the FIT and findings of disease activity on endoscopy are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Correlation between fecal immunochemical test and mayo endoscopic subscore. FIT was positively correlated with endoscopic activity (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient = 0.626, P < 0.01). MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; FIT: Fecal immunochemical test.

Correlation between FIT and the extent of disease

Eighty two cases of colonoscopy were classified according to the extent of disease, where the extent of UC was defined using the Montreal Classification. The distribution of cases was as follows: 20 patients (24.4%) were classified in the E1 category; 30 patients (36.6%) in the E2 category; and 32 patients (39.0%) in the E3 category. Among the 47 patients with a negative FIT, the extent of disease was classified as E1 in 12 patients (25.6%), as E2 in 16 patients (34.0%), and as E3 in 19 patients (40.4%). Among the 35 patients with a positive FIT, the extent of disease was classified as E1 in 8 patients (22.9%), as E2 in 14 patients (40.0%), and as E3 in 13 patients (37.1%). As a result, FIT did not correlated with the extent of disease (r = -0.047, P = 0.676).

Correlation between FIT and clinical activity

Among the 82 colonoscopies performed, 38 (46.3%) were performed in patients with clinical remission, with the other 44 (53.7%) were performed in patients with clinical active disease. Among patients in clinical remission, FIT was negative in 31 (81.6%) of 38 cases, with a mean fecal hemoglobin concentration of 6.12 ng/mL (range, negative to 80.9 ng/mL) for this group of patients. Among patients in clinical active disease, FIT was negative in 16 (36.4%) out of 44 cases, with a mean fecal hemoglobin concentration > 167.4 ng/mL (range, negative to > 1000 ng/mL) for this group of patients. The probability of a negative FIT and mean FIT values according to clinical status of UC are reported in Table 6, with MES according to clinical status reported in Table 7. Overall, FIT positively correlated with clinical activity (r = 0.496, P < 0.01).

Table 6.

Negative fecal immunochemical test probability (%) and mean fecal immunochemical test values according to clinical condition

| Clinical condition | Negative FIT (%) | mean FIT (ng/mL) |

| Remission status (n = 38) | 31/38 (81.6) | 6.12 |

| Active status (n = 44) | 16/44 (36.4) | > 167.41 |

Three cases in clinical active were measured more than 1000 ng/mL fecal hemoglobin concentration. FIT: Fecal immunochemical test.

Table 7.

Mayo endoscopic subscore according to clinical condition

| Clinical condition | n (%) |

| Remission status (n = 38) | |

| MES 0 or 1 | 37 (97.4) |

| MES 2 | 1 (2.6) |

| MES 3 | 0 |

| Active status (n = 44) | |

| MES 0 or 1 | 23 (52.3) |

| MES 2 | 14 (31.8) |

| MES 3 | 7 (15.9) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore.

Correlation between FIT and conventional inflammatory markers

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured in all patients. In FIT negative group (n = 47), ESR was normal range (0-10 mm/h) in 15 cases (31.9%) and CRP was normal range (0-0.5 mg/dL) in 38 cases (80.9%). In FIT positive group (n = 35), ESR was higher than the normal ranges in 28 cases (80.0%) and CRP was higher than the normal ranges in 13 cases (37.1%). Mean ESR was 18.47 mm/hr (range, 2-83) in FIT negative group and 31.06 mm/hr (range, 2-118) in FIT positive group. Mean CRP was 0.338 mg/dL (range, 0.01-3.12) in FIT negative group and 1.286 mg/dL (range, 0.01-7.45) in FIT positive group. Statistically, FIT did not correlated with ESR (r = 0.183, P = 0.100) or CRP (r = 0.154, P = 0.167).

DISCUSSION

As the clinical course of UC is characterized by multiple phases of clinical remission and acute exacerbations, continued monitoring of disease status and treatment are required. In particular, identification of disease activity during asymptomatic periods is important inpredictingsubsequent acute exacerbation. With the accumulation of evidence on the value of the status of the mucosa in the disease process of UC, MH has been regarded as an important clinical goal to achieve in patients with UC[3,11]. Studies have in fact indicated that MH can alter the course of UC, reducing the rate of hospitalization and surgery[19]. Therefore, the evaluation of MH is an important component of the treatment and follow-up of patients with UC. Until now, colonoscopy has been regarded as the gold standard to assess mucosal status in patients with UC. However, colonoscopy is burdensome for patients and carries the possibility of exacerbating the disease status. Furthermore in one study, colonoscopy itself may worsen the disease condition in IBD patients, even in remission state[20]. Therefore, frequent colonoscopy, as required for adequate monitoring of UC status, is difficult due to cost and the inconvenience to patients. To overcome this clinical problem, non-invasive markers of MH have been studied. Although ESR and CRP levels have been used as conventional markers of inflammation, the clinical application of these markers is limited as they reflect systemic inflammation and, therefore, are non-specific to inflammation of the mucosa. FC seems to be promising non-invasive marker of mucosal inflammation and several studies have shown its correlation to the severity of mucosal inflammation. The usefulness of FC has been proven in clinical practice, reliably identifying disease activity in patients with UC who had undergone endoscopicexamination and correlating well with the degree of mucosal inflammation[5-9]. Usually, however, FC can only be performed in tertiary institutions, takes several hours to provide results and is expensive. Moreover, it has been reported that FCresults can exhibit large variation, even between stool samples from the same patient collected on the same day[21].

FIT has been reported from several recent studies as another biomarker[12,13,22]. FC estimate the degree of inflammation in the bowel based on the amount of inflammatory cells, whereas FIT measures the amount of blood from the damaged bowel mucosa[22]. Our study demonstrates that fecal hemoglobin can be used as a marker of endoscopic and clinical disease activityin patients with UC, with a negative FIT accurately reflecting MH and disease remission. Therefore, FIT could provide an “easily available” evaluation of MH to assess the effectiveness of therapy aimed at inducing disease remission in patients with UC. FIT would also be appropriate for repeated evaluations of MH, which is required over the course of clinical remission in patients with UC. In this regard, FIT provides the fast results and at a low financial cost, which could allow physicians to monitor patients with UC more easily and frequently.

FC requires 5-10 g of fecal material for analysis while FIT only requires the probe to be placed in a small sample of stool[6,23]. FIT is available even in smaller institutions, including general primary healthcare. As well, FIT has a unique comparative cutoff value to differentiate disease activity and status, whereas a status cutoff value for FC is currently undetermined[23].

The definition of MH in UC has not been clearly established. Older studies had reported the MH to MES 0 or 1[3], whereas more recent studies have reported MH to MES 0 alone[12]. In recent one study, when the MH to MES 0, FIT appears to be more sensitive than FC for predicting MH (FIT, 95% sensitivity; FC, 82% sensitivity)[22].

The ideal biomarker will be able to detect early relapse in asymptomatic period. Our results also provide evidence of the future possibility of using FIT to identify aggravation of the disease status among patients with a positive FIT. As an example, among our patient group, a 57-year-old male patient, diagnosed with UC 5 years prior, was being treated using azathioprine and oral 5-ASA agents. The colonoscopy and FIT were performed while this patient was classified as being in clinical remission. Although endoscopy findings were negative, with MES of “1” and disease status of E1, a fecal hemoglobin concentration of 74.1 μg/dL was identified on the FIT. Three months later, the patient showed worsening of his clinical symptoms, including persistent bleeding. Sigmoidoscopy conducted at the time of disease exacerbation classified the mucosa as a MES of “3”. The patient’s symptoms improved after his doses of azathioprine and oral 5-ASA were adjusted. One previous study reported that FIT became higher prior to clinical relapse in some UC patients[17]. In order to accurately prove whether the FIT or FC can detect subclinical relapse in early, well designed studies are required.

The limitations of our study need to be acknowledged in the interpretation and application of our results. First, we conducted a retrospective, single center study that included a small absolute number of patients with UC. Second, although previous studies have used the OC-SENSOR neo system to measure hemoglobin concentrations < 50 ng/mL, in our study we used the HM-JACK system that can detect a negative FIT at < 7 ng/mL. With a lower discrimination threshold, a negative FIT can be a very sensitive test of disease status. Nevertheless, the correlation between the MES “0” and a negative FIT was 100% in our study. Third, all patients did not enforce the same day as the fecal sampling and colonoscopy. Although the fecal sampling 1 wk before or after the colonoscopy, FIT and mucosa state may not be exact match as temporally. Forth, only a single fecal sample was obtained from each patient thus individual variation and sampling variation can arise and lead to incorrect results.

In conclusion, our results show that FIT was a reliable tool to identify the inflammation status of colonic mucosa in patients with UC, especially for identifying clinical and endoscopic remission. As FIT was positively correlated with clinical status, a negative FIT could be regarded as an indication of endoscopic and clinical remission. With a positive FIT, careful observation and follow-up is recommended. Sequential testing using FIT could be helpful to monitor disease activity and to inform clinical decisions to modify treatment, including increasing dose of medication. Therefore, FIT can bean effective test which can assess the disease activity in patients with UC.

COMMENTS

Background

To date, the evaluation of mucosal inflammation with colonoscopy is the gold standard to assess disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). However, colonoscopic examination is difficult to frequently perform due to cost and inconvenience to patients. Therefore, identification of non-invasive biomarkers of disease activity in UC is a research priority.

Research frontiers

Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is one of them suggested association with mucosa healing in some studies.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The presented results have identified that FIT correlated positively with endoscopic activity and clinical remission, but not with extent of disease. In particular a negative FIT could be regarded as an indication of endoscopic and clinical remission.

Applications

FIT can be a non-invasive and economic biomarker in patients with UC.

Peer-review

In this retrospective study, authors aimed to evaluate the efficacy of quantitative FIT as biomarker of disease activity in UC. This study shows that fit was a reliable tool to identify the inflammation status of colonic mucosa in patients with UC.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Peer-review started: July 21, 2016

First decision: October 11, 2016

Article in press: November 16, 2016

P- Reviewer: Yuksel I S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pineton de Chambrun G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lémann M, Colombel JF. Clinical implications of mucosal healing for the management of IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, Esser D, Wang Y, Lang Y, Marano CW, Strauss R, Oddens BJ, Feagan BG, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1194–1201. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardizzone S, Cassinotti A, Duca P, Mazzali C, Penati C, Manes G, Marmo R, Massari A, Molteni P, Maconi G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:483–489.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:15–22. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa F, Mumolo MG, Bellini M, Romano MR, Ceccarelli L, Arpe P, Sterpi C, Marchi S, Maltinti G. Role of faecal calprotectin as non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:642–647. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, Bellini M, Romano MR, Sterpi C, Ricchiuti A, Marchi S, Bottai M. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:364–368. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Trummler M, Renzulli P, Seibold F. Ulcerative colitis: correlation of the Rachmilewitz endoscopic activity index with fecal calprotectin, clinical activity, C-reactive protein, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1851–1858. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, Romero Y, Armstrong D, Schmidt C, Trummler M, Pittet V, Vavricka SR. Fecal calprotectin more accurately reflects endoscopic activity of ulcerative colitis than the Lichtiger Index, C-reactive protein, platelets, hemoglobin, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:332–341. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182810066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LS, Yen AM, Chiu SY, Liao CS, Chen HH. Baseline faecal occult blood concentration as a predictor of incident colorectal neoplasia: longitudinal follow-up of a Taiwanese population-based colorectal cancer screening cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:551–558. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, Noman M, Arijs I, Van Assche G, Hoffman I, Van Steen K, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1295–1301. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakarai A, Kato J, Hiraoka S, Kuriyama M, Akita M, Hirakawa T, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Evaluation of mucosal healing of ulcerative colitis by a quantitative fecal immunochemical test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:83–89. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooiweer E, Fidder HH, Siersema PD, Laheij RJ, Oldenburg B. Fecal hemoglobin and calprotectin are equally effective in identifying patients with inflammatory bowel disease with active endoscopic inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:307–314. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000438428.30800.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, Maaser C, Chowers Y, Geboes K, Mantzaris G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Vermeire S, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965–990. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A–36A. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuriyama M, Kato J, Takemoto K, Hiraoka S, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Prediction of flare-ups of ulcerative colitis using quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1110–1114. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menees S, Higgins P, Korsnes S, Elta G. Does colonoscopy cause increased ulcerative colitis symptoms? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:12–18. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasson A, Stotzer PO, Öhman L, Isaksson S, Sapnara M, Strid H. The intra-individual variability of faecal calprotectin: a prospective study in patients with active ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato J, Hiraoka S, Nakarai A, Takashima S, Inokuchi T, Ichinose M. Fecal immunochemical test as a biomarker for inflammatory bowel diseases: can it rival fecal calprotectin? Intest Res. 2016;14:5–14. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilkin A, Rozen P, Levi Z, Waked A, Maoz E, Birkenfeld S, Niv Y. Performance characteristics and evaluation of an automated-developed and quantitative, immunochemical, fecal occult blood screening test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2519–2525. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]