Abstract

AIM

To assess the prevalence of possible risk factors of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and their age-group specific trend among the general population and osteoarthritis patients.

METHODS

We utilized data from the National Health Insurance Service that included claims data and results of the national health check-up program. Comorbid conditions (peptic ulcer, diabetes, liver disease, chronic renal failure, and gastroesophageal reflux disease), concomitant drugs (aspirin, clopidogrel, cilostazol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroid, anticoagulants, and SSRI), personal habits (smoking, and alcohol consumption) were considered as possible UGIB risk factors. We randomly imputed the prevalence of infection in the data considering the age-specific prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Korea. The prevalence of various UGIB risk factors and the age-group specific trend of the prevalence were identified. Prevalence was compared between osteoarthritis patients and others.

RESULTS

A total of 801926 subjects (93855 osteoarthritis patients) aged 20 and above were included. The prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors became higher as the age increased. The prevalence of each comorbid condition and concomitant drug were higher in osteoarthritis patients. Thirty-five point zero two percent of the overall population and 68.50% of osteoarthritis patients had at least one or more risk factors of UGIB. The prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors in younger age groups were also substantial. Furthermore, when personal habits (smoking, and alcohol consumption) and H. pylori infection were included, the prevalence of concurrent multiple risk factors increased greatly even in younger age groups.

CONCLUSION

Prevalence of UGIB risk factors was high in elderly population, but was also considerable in younger population. Patient with osteoarthritis was at higher UGIB risk than those without osteoarthritis. Physicians should consider individualized risk assessment regardless of age when prescribing drugs or performing procedures that may increase the risk of UGIB, and take necessary measures to reduce modifiable risk factors such as H. pylori eradication or lifestyle counseling.

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding, Prevalence, Risk factor, General population, Osteoarthritis

Core tip: This study identified the prevalence of various upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) risk factors and the age-group specific trend of the prevalence in general population and osteoarthritis patients using large population representative data. Considering the age-group specific trend of the prevalence of UGIB risk factors, physicians should consider individualized risk assessment regardless of age when prescribing drugs or performing procedures that predispose to UGIB. Additionally, subjects with high risk should control modifiable UGIB risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in medical science, upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is still a high risk condition with high morbidity and mortality[1]. Rotondano et al[2] reported that the overall mortality rate of UGIB was approximately 5%. Although its incidence is decreasing worldwide, a substantial amount of patients are still suffering from UGIB[3]. In the United States, the incidence of UGIB was approximately 60.6 per 100000 in 2009[4]. Furthermore, the proportion of aspirin- or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-related UGIB is also increasing[5]. This has led to incurrence of substantial costs[6].

The high mortality and economic burden of UGIB have raised concerns regarding risk factors for the disease. In general, UGIB occurs more frequently in the male sex and advancing age[7,8]. Additionally, many underlying diseases, drugs, and unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., smoking) are proven risk factors of UGIB[3,8-27]. Also, the increasing trend of NSAIDS-induced UGIB has also led to research focusing on arthritis patients, who are potential long-term consumers of these predisposing drugs[28-31].

While several studies have identified significant risk factors of UGIB, many focused on assessing the relative risks of each factor in a specific population group only, not the general population. To the best of our knowledge, to date, no large general-population-based studies have investigated the epidemiology of UGIB risk factors.

In this study, we assessed the prevalence of possible risk factors of UGIB and their age-group specific trend among the general population, and compared the prevalence between patients with osteoarthritis and others.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

This study utilized data from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) (NHIS-2015-2-099), compiled by the NHIS. The National Health Insurance in South Korea covers approximately 98% of the population, ensuring generalization of data[32]. The original claims data included 90% of the population in South Korea. Using a randomized stratified sampling method, the NHIS provided 2% samples of cohorts of the claims data from 2002 to 2013. Detailed explanation of the data structure is provided elsewhere[33]. To investigate recent epidemiology, we used the claims data of outpatient visits in 2013. In addition, to take into account subjects’ personal habits, we used results from the national health check-up program cohorts in 2013, which included lifestyle and medical information, as well as biochemical markers. NHIS provides both claims data and results of national health check-up programs through an online review system (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba000eng.do).

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. E-1508-002-689).

Risk factors of UGIB

From a literature review of previous studies, we identified the possible risk factors of UGIB. We subdivided risk factors into 3 categories: (1) comorbid conditions; (2) concomitant drugs; and (3) personal habit. Comorbid conditions included peptic ulcer[8,10,16], diabetes mellitus[15], liver disease[14], chronic renal failure[3,17,18], and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)[3]. Concomitant drugs included oral aspirin[3,8,11,15,21], other antiplatelet agents including cilostazol and clopidogrel[3,11], NSAIDs[3,8,10,11,16,29], steroids[3,19], anticoagulants including warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban[3,10,11], and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors[3,23,24]. As selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors had been prescribed to reduce the gastrointestinal complications, these drugs were not included as concomitant drugs[31,34,35]. Personal habits included smoking[8,10,11], and alcohol consumption[8,10,11].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection was also considered as a possible independent risk factor[3,8,10,13,16].

Definition of variables

We defined cases of comorbid conditions based on the ICD-10 codes: “K25.X”, “K26.X”, “K27.X”, and “K28.X” for peptic ulcer; “E08.X”, “E09.X”, “E10.X”, “E11.X”, “E12.X”, “E13.X”, and “E14.X” for diabetes; “K70.X”, “K71.X”, “K72.X”, “K73.X”, “K74.X”, “K75.X”, “K76.X”, and “K77.X” for liver disease; “N18.X” for chronic renal failure; “K21.X”, and “K221” for GERD. Cases of comorbid conditions were defined if any of the above-mentioned relevant ICD-10 codes was the main diagnosis (for which the patient primarily presented with), or the first additional diagnosis (that the patient was already being treated for or was diagnosed at the same visit as the main diagnosis). Subjects with “M15.X” to “M19.X” ICD-10 codes as the main or the first additional diagnosis were defined as patients with osteoarthritis.

Although short-term use of some drugs could increase the risk of UGIB[36], we aimed to identify longer-term users of predisposing drugs, especially those with the potential to consume these drugs for life. Therefore, we only included subjects who had been prescribed drugs for at least 60 d as cases of concomitant drug users.

Smoking was subdivided into 2 categories: (1) non- or former smoker; and (2) current smoker. Problematic alcohol consumption was defined as follows: men who drink more than 4 standard drinks a day or 14 standard drinks a week; women who drink more than 3 standard drinks a day or 7 standard drinks a week; and subjects aged 65 or more who drink more than 1 standard drink a day or 7 standard drinks a week. One standard drink contains approximately 14 g of alcohol[37].

Statistical analysis

Subjects aged 20 and above were included in our analysis. First, we calculated the prevalence of each risk factor within the general population and it was compared between osteoarthritis patients and others. To identify subjects with concurrent multiple risk factors, we categorized subjects into 3 categories: (1) those with 1 or more risk factors; (2) those with 2 or more risk factors; and (3) those with 3 or more risk factors or more. As patients with osteoarthritis potentially consume NSAIDs[31], we additionally calculated the prevalence after excluding NSAIDs as a concomitant drug for osteoarthritis patients. Additionally, age-group specific prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors were calculated. Since the data did not provide information about H. pylori infection, we formulated a statistical method to consider this infection. Considering the age-specific prevalence of H. pylori infection in Korea from a representative large cohort study, we randomly imputed the prevalence of infection in the data[38]. The reported prevalence of H. pylori infection was 26.4, 42.1, 52.6, 61.4, 61.6, and 58.6 % for subjects in their 20 s, 30 s, 40 s, 50 s, 60 s, and 70 s (or more), respectively. Following random imputation, prevalence of concurrent multiple risk factors were calculated.

As mentioned above, we included personal habits as risk factors of UGIB. However, information regarding subjects’ personal habits was only available in those who participated in the national health check-up program in 2013. Subgroup analysis was performed to take into account the lifestyle factors in these subjects.

To address the possible differences of the definition of concomitant drug user, sensitivity analysis was performed. Subjects who have been prescribed the drugs for at least 30 d were considered as cases of concomitant drug users.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the STATA software version 14.0 (StataCorp., TX).

RESULTS

A total of 801926 subjects from the general population aged 20 or more (93855 were patients with osteoarthritis) were included in the analysis. Out of this, 233879 subjects participated in the national health check-up program in 2013. The age- and sex-specific distributions of the study population are provided in online only supplementary Table 1.

Table 1 shows the overall prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors. GERD was the most frequent comorbid condition associated with UGIB in the overall population, subjects without osteoarthritis, and patients with osteoarthritis (14.10%, 12.67%, and 26.60%, respectively). Although aspirin was the most frequently used predisposing drug in the overall population (6.63%), NSAIDs had the highest prevalence in osteoarthritis patients (28.42%). The prevalence of each comorbid condition and concomitant drug usage were also higher in these patients compared to the general population. We found that 35.02% of the overall population and 68.50% of osteoarthritis patients had at least one or more risk factors of UGIB. More than 16% of subjects with osteoarthritis had 3 or more concurrent risk factors. Even when NSAIDs were excluded for prevalence calculation of concurrent multiple risk factors, the prevalence of osteoarthritis patients with at least one or more risk factors decreased by only 8%. When H. pylori infection was considered, the prevalence of concurrent multiple risk factors increased approximately 2-fold in the overall population. The increase in the prevalence of osteoarthritis patients was also substantial. All P values for each risk factor from the chi square test between subjects without osteoarthritis and osteoarthritis patients were below 0.001.

Table 1.

Prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding risk factors

| Overall Population (n = 801926 ) | Without Osteoarthritis (n = 708107) | Osteoarthritis Patients (n = 93855) | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Peptic ulcer | 9.15% | 7.85% | 19.00% |

| Diabetes | 8.33% | 7.04% | 18.12% |

| Chronic liver disease | 5.76% | 5.28% | 9.32% |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.49% | 0.44% | 0.83% |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 14.30% | 12.67% | 26.60% |

| Concomitant drugs1 | |||

| Aspirin | 6.63% | 5.41% | 15.86% |

| Clopidogrel | 1.78% | 1.43% | 4.44% |

| Cilostazol | 0.66% | 0.51% | 1.76% |

| NSAIDs | 5.99% | 3.02% | 28.42% |

| Steroid | 1.28% | 0.93% | 3.94% |

| Anticoagulants2 | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.36% |

| SSRI | 0.44% | 0.37% | 1.00% |

| No. of risk factors | |||

| ≥ 1 | 35.02% | 30.58% | 68.50% |

| ≥ 2 | 13.87% | 10.66% | 38.04% |

| ≥ 3 | 4.52% | 2.97% | 16.25% |

| No. of risk factors | |||

| (Excluding concomitant NSAIDs Use) | |||

| ≥ 1 | 33.10% | 29.49% | 60.40% |

| ≥ 2 | 11.81% | 9.63% | 28.26% |

| ≥ 3 | 3.22% | 2.38% | 9.60% |

| No. of risk factors | |||

| (After H. pylori prevalence imputation) | |||

| ≥ 1 | 64.57% | 62.16% | 82.76% |

| ≥ 2 | 23.26% | 20.08% | 47.19% |

| ≥ 3 | 8.12% | 6.47% | 20.60% |

Subjects who were prescribed 60 d or more in 2013;

Warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban were included. All P values from the χ2 test between subjects without osteoarthritis and arthritis patients are below 0.001. NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

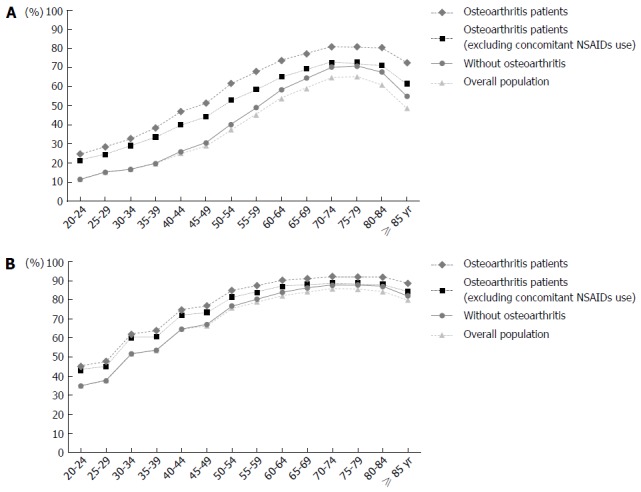

Figure 1 shows the age-group specific trend of prevalence with at least one risk factor. Prevalence of UGIB risk factors increases with age, with the highest value seen among the 70-79 year-old age group. The age-group specific prevalence of UGIB risk factors among osteoarthritis patients is provided in online only supplementary Table 2.

Figure 1.

Age-group specific prevalence of any upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk factors. A: Without Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence imputation; B: With H. pylori prevalence imputation; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

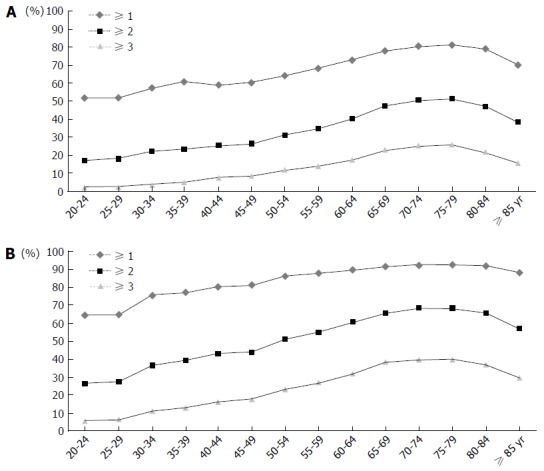

The increased prevalence of UGIB risk factors with age was consistently noted in the overall population, peaking among subjects in their 70 s (Table 2). For subjects who participated in the national health check-up program, the prevalence of multiple risk factors increased naturally as 2 more risk factors (smoking, and alcohol consumption) were considered (Figure 2). The number of smokers and alcohol consumers generally decreased with age. As the criteria for alcohol consumption changed at the age of 65, the prevalence of problematic drinking increased at the age-group (see online only supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Age-group specific prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding risk factors in overall population

| 20-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | 45-49 | 50-54 | 55-59 | 60-64 | 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | ≥ 85 yr | |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||||||||||

| Peptic ulcer | 3.84% | 4.80% | 4.92% | 5.49% | 7.61% | 8.47% | 10.87% | 12.45% | 14.20% | 15.49% | 17.50% | 16.08% | 13.72% | 9.95% |

| Diabetes | 0.31% | 0.49% | 0.96% | 1.76% | 3.27% | 5.68% | 8.78% | 13.17% | 18.18% | 22.04% | 25.48% | 25.96% | 23.55% | 16.13% |

| Chronic liver disease | 2.17% | 2.99% | 3.74% | 4.40% | 4.76% | 5.99% | 7.55% | 8.68% | 9.09% | 9.03% | 8.01% | 6.91% | 5.65% | 3.96% |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.03% | 0.06% | 0.09% | 0.14% | 0.23% | 0.28% | 0.39% | 0.59% | 0.88% | 1.13% | 1.66% | 1.84% | 1.96% | 1.66% |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux disease | 6.02% | 8.34% | 8.88% | 9.92% | 13.22% | 13.63% | 17.18% | 19.11% | 22.11% | 22.85% | 23.93% | 20.94% | 17.29% | 11.43% |

| Concomitant drugs1 | ||||||||||||||

| Aspirin | 0.03% | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.42% | 1.15% | 2.65% | 5.66% | 10.21% | 15.55% | 19.84% | 24.26% | 25.57% | 25.15% | 19.66% |

| Clopidogrel | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.03% | 0.09% | 0.27% | 0.56% | 1.10% | 2.13% | 3.66% | 5.18% | 7.23% | 8.59% | 9.41% | 7.19% |

| Cilostazol | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.03% | 0.11% | 0.23% | 0.48% | 0.86% | 1.36% | 1.98% | 2.59% | 3.09% | 2.96% | 2.17% |

| NSAIDs | 0.48% | 0.66% | 1.00% | 1.65% | 2.28% | 3.58% | 6.19% | 8.77% | 11.81% | 15.27% | 18.31% | 19.83% | 19.57% | 14.99% |

| Steroid | 0.27% | 0.35% | 0.44% | 0.59% | 0.72% | 0.91% | 1.23% | 1.64% | 2.18% | 2.99% | 3.60% | 3.80% | 3.48% | 2.50% |

| Anticoagulants2 | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.03% | 0.04% | 0.06% | 0.09% | 0.15% | 0.23% | 0.32% | 0.47% | 0.68% | 0.88% | 0.68% | 0.46% |

| SSRI | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.21% | 0.24% | 0.29% | 0.38% | 0.41% | 0.59% | 0.92% | 1.23% | 1.57% | 1.88% | 1.41% |

| No. of risk factors | ||||||||||||||

| ≥ 1 | 11.53% | 15.26% | 16.72% | 19.63% | 25.88% | 30.45% | 40.22% | 49.00% | 58.39% | 64.43% | 70.27% | 70.69% | 67.59% | 54.93% |

| ≥ 2 | 1.66% | 2.42% | 3.23% | 4.36% | 6.59% | 9.35% | 14.79% | 20.87% | 28.01% | 33.92% | 39.74% | 40.03% | 36.67% | 25.34% |

| ≥ 3 | 0.16% | 0.25% | 0.39% | 0.67% | 1.22% | 2.10% | 3.92% | 6.44% | 10.06% | 13.44% | 17.08% | 16.97% | 15.05% | 8.48% |

| No. of risk factors | ||||||||||||||

| (After H. pylori prevalence imputation) | ||||||||||||||

| ≥ 1 | 34.84% | 37.72% | 51.60% | 53.61% | 64.84% | 67.08% | 76.84% | 80.34% | 83.99% | 86.35% | 87.86% | 87.91% | 86.93% | 82.20% |

| ≥ 2 | 4.24% | 5.79% | 8.93% | 10.81% | 16.85% | 20.48% | 30.34% | 38.05% | 46.72% | 52.90% | 57.54% | 57.88% | 54.60% | 42.92% |

| ≥ 3 | 0.54% | 0.83% | 1.60% | 2.26% | 4.04% | 5.87% | 10.63% | 15.35% | 21.22% | 26.20% | 30.43% | 30.36% | 27.95% | 18.31% |

Subjects who were prescribed 60 d or more in 2013;

Warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban were included. NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Age-Group Specific Prevalence of Multiple Risk Factors in Subjects Performed Health Check-up. A: Without Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence imputation; B: With H. pylori prevalence imputation. Smoking and problematic alcohol drinking were included as risk factors additionally.

In the sensitivity analysis, although the prevalence of each concomitant drug usage was slightly decreased, the prevalence did not vary much from that of the main analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis for prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding risk factors in overall population (%)

| 20-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | 45-49 | 50-54 | 55-59 | 60-64 | 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | ≥ 85 yr | |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||||||||||

| Peptic ulcer | 3.84% | 4.80% | 4.92% | 5.49% | 7.61% | 8.47% | 10.87% | 12.45% | 14.20% | 15.49% | 17.50% | 16.08% | 13.72% | 9.95% |

| Diabetes | 0.31% | 0.49% | 0.96% | 1.76% | 3.27% | 5.68% | 8.78% | 13.17% | 18.18% | 22.04% | 25.48% | 25.96% | 23.55% | 16.13% |

| Chronic liver disease | 2.17% | 2.99% | 3.74% | 4.40% | 4.76% | 5.99% | 7.55% | 8.68% | 9.09% | 9.03% | 8.01% | 6.91% | 5.65% | 3.96% |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.03% | 0.06% | 0.09% | 0.14% | 0.23% | 0.28% | 0.39% | 0.59% | 0.88% | 1.13% | 1.66% | 1.84% | 1.96% | 1.66% |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 6.02% | 8.34% | 8.88% | 9.92% | 13.22% | 13.63% | 17.18% | 19.11% | 22.11% | 22.85% | 23.93% | 20.94% | 17.29% | 11.43% |

| Concomitant drugs1 | ||||||||||||||

| Aspirin | 0.04% | 0.09% | 0.18% | 0.50% | 1.26% | 2.84% | 5.97% | 10.67% | 16.17% | 20.60% | 25.24% | 26.59% | 26.35% | 20.75% |

| Clopidogrel | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.04% | 0.10% | 0.28% | 0.59% | 1.17% | 2.25% | 3.83% | 5.47% | 7.58% | 9.03% | 10.00% | 7.75% |

| Cilostazol | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.02% | 0.04% | 0.13% | 0.25% | 0.54% | 0.96% | 1.48% | 2.15% | 2.83% | 3.39% | 3.21% | 2.45% |

| NSAIDs | 2.34% | 3.31% | 4.56% | 6.29% | 7.35% | 9.96% | 14.69% | 18.52% | 23.02% | 27.50% | 31.07% | 31.68% | 30.34% | 22.76% |

| Steroid | 0.88% | 1.07% | 1.28% | 1.62% | 1.88% | 2.21% | 2.91% | 3.50% | 4.43% | 5.54% | 6.59% | 6.72% | 6.07% | 4.58% |

| Anticoagulants2 | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.03% | 0.04% | 0.07% | 0.10% | 0.16% | 0.25% | 0.34% | 0.53% | 0.73% | 0.96% | 0.73% | 0.50% |

| SSRI | 0.21% | 0.22% | 0.21% | 0.27% | 0.32% | 0.38% | 0.50% | 0.55% | 0.74% | 1.13% | 1.53% | 1.89% | 2.13% | 1.70% |

| No. of risk factors | ||||||||||||||

| (without H. pylori prevalence imputation) | ||||||||||||||

| ≥ 1 | 13.32% | 17.55% | 19.61% | 23.22% | 29.38% | 34.49% | 44.88% | 53.68% | 62.87% | 68.98% | 74.57% | 74.65% | 71.74% | 58.61% |

| ≥ 2 | 2.25% | 3.29% | 4.42% | 5.97% | 8.57% | 11.89% | 18.42% | 24.98% | 33.02% | 39.09% | 45.26% | 45.36% | 41.69% | 29.63% |

| ≥ 3 | 0.29% | 0.48% | 0.74% | 1.18% | 1.99% | 3.20% | 5.72% | 8.93% | 13.23% | 17.29% | 21.32% | 21.25% | 18.75% | 11.07% |

| No. of risk factors | ||||||||||||||

| (after H. pylori prevalence imputation) | ||||||||||||||

| ≥ 1 | 36.21% | 39.37% | 53.24% | 55.64% | 66.45% | 68.97% | 78.69% | 82.11% | 85.68% | 88.13% | 89.66% | 89.52% | 88.55% | 83.72% |

| ≥ 2 | 5.12% | 7.08% | 10.87% | 13.30% | 19.66% | 23.81% | 34.58% | 42.48% | 51.41% | 57.73% | 62.40% | 62.59% | 59.14% | 46.84% |

| ≥ 3 | 0.78% | 1.21% | 2.32% | 3.24% | 5.45% | 7.75% | 13.52% | 18.90% | 25.56% | 30.79% | 35.35% | 35.09% | 32.49% | 21.95% |

Subjects who were prescribed 60 d or more in 2013;

Warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban were included. NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple UGIB risk factors in the general population and patients with osteoarthritis. We also identified the trend of age-group specific prevalence of UGIB risk factors. Large sample size with systematic sampling method ensures the generalization of the results. Moreover, the unique dataset from NHIS enabled us to address multiple personal habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption, as well as comorbid diseases and drugs.

Our findings showed that age was associated with increased prevalence of UGIB risk factors, consistent with previous studies[7,8]. Naturally, the prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors became higher as the age increased. However, the prevalence of UGIB risks in younger subjects was also substantial. In the overall population, more than 14% of subjects aged 50-54 years old already had 2 or more risk factors. When H. pylori infection was considered, the prevalence of 3 or more risk factors is 10% in this age group. Furthermore, approximately 50% of subjects aged 30-34 years old had at least one risk factor. This is even more evident when we included personal habits as risk factors.

Patients with osteoarthritis have a higher prevalence of concurrent multiple risk factors compared to the subjects without, even after excluding NSAIDs. When NSAIDs were excluded, the difference of age-group specific prevalence of having at least one risk factor between the subjects without osteoarthritis and osteoarthritis patients became smaller. However, this difference of prevalence became larger as age decreases, suggesting that young osteoarthritis patients have more underlying risk factors than the subjects without osteoarthritis.

Our findings have important clinical implications: First, elderly subjects are at high risk for UGIB by not only due to their age, but also multiple comorbid conditions and concomitant drug usage. Furthermore, increasing age is associated with UGIB occurrence, recurrence, and mortality[8]. Physicians with elderly patients should, therefore, identify measures to reduce the occurrence of UGIB in this population.

Second, our study revealed that a considerable portion of young adults has concurrent multiple risk factors of UGIB. When H. pylori infection was considered, more than 10% of the general population aged 35-39 had 2 or more UGIB risk factors. When we took into account subjects’ personal habits, more than 60% of those aged 20-24 factors, physicians should consider individualized risk assessment for UGIB of already had at least one UGIB risk factor. Given that osteoarthritis patients are likely to consume NSAIDs and possess higher prevalence of UGIB risk in NSAIDs prescription, regardless of patients’ age[30]. Selective COX-2 inhibitors or concurrent prescription of proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol may be a good option for osteoarthritis patients with high risk of UGIB[28,34,35,39,40].

Finally, identifying and controlling modifiable risk factors is of great importance. The majority of subjects who already consume the above-mentioned drugs are those who require them long-term, possibly lifelong. In addition, most of the comorbid conditions related to UGIB are intractable chronic disease. Therefore, these high-risk subjects should control any modifiable risk factors of UGIB, such as smoking, heavy drinking, and H. pylori infection[27,35]. Also, further prospective studies are needed to address the issue of other lifestyle modification and UGIB prevention.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not include other risk factors apart from the ones studied. For instance, drug-drug interaction and drug dosage (both of which increase the risk of UGIB) were not considered[19,25]. Furthermore, some drugs may cause UGIB even with short-term use[36]. Additionally, we used imputation of H. pylori infection prevalence from a cohort study[38]. This might affect the prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors of UGIB. More detailed information about individual-level risks may give rise to a different prevalence. However, the difference in prevalence between the main and sensitivity analysis was not high, supporting the reliability of the results. Finally, ICD-10 codes based definition of osteoarthritis may not meet the specific diagnostic criteria. However, claims with such osteoarthritis diagnosis are usually made with clinical features which are consistent with symptoms and signs of osteoarthritis, and are accompanied by prescription of NSAIDS, which increases the risk of UGIB. In addition, claims data has its own strengths in terms of large sample size, representativeness, and generalizability to the real world setting.

We investigated the prevalence of various risk factors of UGIB in the general population and osteoarthritis patients. Physicians should consider individualized risk assessment regardless of age when prescribing drugs or performing procedures that may increase the risk of UGIB, and take necessary measures to reduce modifiable risk factors such as H. pylori eradication or lifestyle counseling.

COMMENTS

Background

Despite advances in medical science, upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is still a high risk condition with high morbidity and mortality. Although its incidence is decreasing worldwide, a substantial amount of patients are still suffering from UGIB. Furthermore, the proportion of aspirin- or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-related UGIB is also increasing.

Research frontiers

While several studies have identified significant risk factors of UGIB, many focused on assessing the relative risks of each factor in a specific population group only, not the general population. To the best of our knowledge, to date, no large general-population-based studies have investigated the epidemiology of UGIB risk factors. The research hotspot is to assess the prevalence of various UGIB risk factors among the general population, and compared the prevalence between patients with osteoarthritis and others.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first study to investigate the prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple UGIB risk factors in the general population and patients with osteoarthritis. The authors also identified the trend of age-group specific prevalence of UGIB risk factors. The prevalence of individual and concurrent multiple risk factors became higher as the age increased. However, the prevalence of UGIB risks in younger subjects was also substantial. In addition, patients with osteoarthritis have a higher prevalence of concurrent multiple risk factors compared to the general population.

Applications

Present study has important clinical implications. First, elderly subjects are at high risk for UGIB by not only due to their age, but also multiple comorbid conditions and concomitant drug usage. Second, physicians should always bear in mind the possibility of UGIB, regardless of age. Finally, identifying and controlling modifiable risk factors is of great importance.

Peer-review

In the presented article the prevalence of possible risk factors of UGIB among general population and patients with osteoarthritis were assessed. The prevalence of risk factors were higher in patients with osteoarthritis compared to general population

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital, No. E-1508-002-689.

Informed consent statement: As this study was an observational study and we used data from the public repository (National Health Insurance Service Sharing Service, https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ay/bdaya001iv.do;jsessionid=3xOUDsw6a2QK3ySYMpQ89I3lkGUasr6famrJXqsPHnXUv5ZSQHwSrTY3jZiuZLPh.primrose2_servlet_engine1), informed consent was exempted (IRB No. E-1508-002-689).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author from email of DW Shin (dwshin.snuh@gmail.com). The presented data are anonymized and risk of identification is low. As the data is owned to the National Health Insurance, institutional approval must precede before providing the dataset.

Peer-review started: August 5, 2016

First decision: September 12, 2016

Article in press: October 31, 2016

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Koch TR, Ozen H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327–1335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotondano G. Epidemiology and diagnosis of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:643–663. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tielleman T, Bujanda D, Cryer B. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laine L, Yang H, Chang SC, Datto C. Trends for incidence of hospitalization and death due to GI complications in the United States from 2001 to 2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1190–1195; quiz 1196. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohmann C, Imhof M, Ruppert C, Janzik U, Vogt C, Frieling T, Becker K, Neumann F, Faust S, Heiler K, et al. Time-trends in the epidemiology of peptic ulcer bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:914–920. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laine L, Peterson WL. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:717–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, Metz DC. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84:102–113. doi: 10.1159/000323958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper JM, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Corticosteroid use and peptic ulcer disease: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:735–740. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-9-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanas Á, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Arguedas Y, García S, Bujanda L, Calvet X, Ponce J, Perez-Aísa Á, Castro M, Muñoz M, Sostres C, García-Rodríguez LA. Risk of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:906–912.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massó González EL, Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, García Rodríguez LA. Variability among nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1592–1601. doi: 10.1002/art.27412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iijima K, Kanno T, Koike T, Shimosegawa T. Helicobacter pylori-negative, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug: negative idiopathic ulcers in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:706–713. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i3.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo JC, Leu HB, Hou MC, Huang CC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Chan WL, Lin SJ, Chen JW. Cirrhotic patients at increased risk of peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:542–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, Pellegrini F, Lepore V, Tognoni G, Nicolucci A. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307:2286–2294. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sostres C, Lanas A. Epidemiology and demographics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: prevalence, incidence, and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JY, Lee TC, Montez-Rath ME, Paik J, Chertow GM, Desai M, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:495–506. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011070658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalman RS, Pedrosa MC. Evidence-based review of gastrointestinal bleeding in the chronic kidney disease patient. Semin Dial. 2015;28:68–74. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutthann SP, García Rodríguez LA, Raiford DS. Individual nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and other risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Epidemiology. 1997;8:18–24. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock S, Jørgensen T, Bonnevie O, Andersen L. Risk factors for peptic ulcer disease: a population based prospective cohort study comprising 2416 Danish adults. Gut. 2003;52:186–193. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valkhoff VE, Sturkenboom MC, Kuipers EJ. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding associated with low-dose aspirin. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García Rodríguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994;343:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, Tse F, Armstrong D, Leontiadis GI. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811–819. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paton C, Ferrier IN. SSRIs and gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ. 2005;331:529–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vonbach P, Reich R, Möll F, Krähenbühl S, Ballmer PE, Meier CR. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding: a hospital-based case-control study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:705–710. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters HP, De Vries WR, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Akkermans LM. Potential benefits and hazards of physical activity and exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2001;48:435–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, Chrischilles EA, Brown SL, Wallace RB. Physical activity and risk of severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage in older persons. JAMA. 1994;272:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasef SA, Shaaban AA, Mould-Quevedo J, Ismail TA. The cost-effectiveness of celecoxib versus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs plus proton-pump inhibitors in the treatment of osteoarthritis in Saudi Arabia. Health Econ Rev. 2015;5:53. doi: 10.1186/s13561-015-0053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laine L, Harper S, Simon T, Bath R, Johanson J, Schwartz H, Stern S, Quan H, Bolognese J. A randomized trial comparing the effect of rofecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2-specific inhibitor, with that of ibuprofen on the gastroduodenal mucosa of patients with osteoarthritis. Rofecoxib Osteoarthritis Endoscopy Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:776–783. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Bh, Shin BJ, Kim DJ, Lee JC, Suk KS, Park YS, Kim KW, Cho KJ, Shin KY, Koh MS, Moon SH. Gastrointestinal Risk Assessment in the Patients Taking Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammarory Drugs for Lumbar Spinal Disease. J Korean Society Spine Surg. 2011;18:239. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SH, Han CD, Yang IH, Ha CW. Prescription pattern of NSAIDs and the prevalence of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal risk factors of orthopaedic patients in clinical practice in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:561–567. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ChangBae C, SoonYang K, JunYoung L, SangYi L. Republic of Korea. Health system review. Health Systems Transit. 2009;11:1–184. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SH, Cho BL, Shin DW, Hwang SS, Lee H, Ahn EM, Yun JM, Chung YH, Nam YS. The Effect of Asthma Clinical Guideline for Adults on Inhaled Corticosteroids PrescriptionTrend: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:1048–1054. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:728–738. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks J, Warburton R, Beales IL. Prevention of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: current controversies and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4:206–222. doi: 10.1177/2040622313492188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang CH, Chen HC, Lin JW, Kuo CW, Shau WY, Lai MS. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal adverse events associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a nationwide case-crossover study in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:763–771. doi: 10.1002/pds.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enoch MA, Goldman D. Problem drinking and alcoholism: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, Kim GH, Kang JM, Park MJ, Yim JY, Kim HU, Baik GH, Seo GS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan JQ, Tsoi KK, Yang M, Wang JY, Threapleton DE, Yang ZY, Zou B, Mao C, Tang JL, Chan FK. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative effectiveness and safety of strategies for preventing NSAID-associated gastrointestinal toxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1262–1275. doi: 10.1111/apt.13642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown TJ, Hooper L, Elliott RA, Payne K, Webb R, Roberts C, Rostom A, Symmons D. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: a systematic review with economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii–iv, xi-xiii, 1-183. doi: 10.3310/hta10380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]