Abstract

Risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes are known to augment the activity and tissue expression of angiotensin II (Ang II), the major effector peptide of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS). Overstimulation of the RAS has been implicated in a chain of events that contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular (CV) disease, including the development of cardiac remodelling. This chain of events has been termed the CV continuum. The concept of CV disease existing as a continuum was first proposed in 1991 and it is believed that intervention at any point within the continuum can modify disease progression. Treatment with antihypertensive agents may result in regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, with different drug classes exhibiting different degrees of efficacy. The greatest decrease in left ventricular mass is observed following treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), which inhibit Ang II formation. Although ACE-Is and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) provide significant benefits in terms of CV events and stroke, mortality remains high. This is partly due to a failure to completely suppress the RAS, and, as our knowledge has increased, an escape phenomenon has been proposed whereby the human sequence of the 12 amino acid substrate angiotensin-(1-12) is converted to Ang II by the mast cell protease, chymase. Angiotensin-(1-12) is abundant in a wide range of organs and has been shown to increase blood pressure in animal models, an effect abolished by the presence of ACE-Is or ARBs. This review explores the CV continuum, in addition to examining the influence of the RAS. We also consider novel pathways within the RAS and how new therapeutic approaches that target this are required to further reduce Ang II formation, and so provide patients with additional benefits from a more complete blockade of the RAS.

Keywords: angiotensin-(1-12), angiotensin II, cardiac remodelling, cardiovascular continuum, renin–angiotensin system (RAS)

Introduction

Risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes are known to stimulate the production of angiotensin II (Ang II), the major effector peptide of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) [Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. The RAS plays a major role in the preservation of haemodynamic stability, with overstimulation of this system implicated in a chain of events that contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular (CV) disease [Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. Over the past two decades, a wealth of research has significantly improved our understanding of CV disease. In particular, we have gained invaluable insights into the chain of events that can ultimately lead to the development of target organ damage, end-organ failure and death [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991; Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. This knowledge has resulted in the hypothesis that CV disease occurs as part of a series of events that form a continuum, which occurs due to the presence of one or more risk factors [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991; Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. These risk factors, which have been shown to have an additive effect, include hypertension, hyperglycaemia, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, left ventricular hypertrophy and obesity [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991; Yusuf et al. 2004; Ferrario sand Strawn, 2006]. Activation of inflammatory mechanisms in response to the tissue injury amplified by the presence of one or more of these risk factors results in the initiation of enhanced RAS activity, which mediates an adaptive and maladaptive response [Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. This in turn plays an important role in the pathophysiology of CV disease, with inflammation being a key mechanism in the initiation, progression and clinical sequelae of CV disease [Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. Intervention at any point along this chain of events has been proposed as a means of disrupting the underlying pathophysiology of CV disease and conferring cardioprotection [Ferrario and Strawn, 2006]. The pleotropic actions of Ang II as a hormone, either mediating or modulating cellular signalling mechanisms stimulating trophic, profibrotic, prothrombotic and native immune responses [Harrison et al. 2011], places blockade of this system at the core of treatment approaches to diseases of the heart and blood vessels. This review examines the stages that exist within this CV continuum, with particular attention on cardiac remodelling and how intervention in the RAS may improve CV outcomes.

The CV continuum

The concept of CV disease existing as part of a continuum was first proposed in 1991 by Dzau and Braunwald in a consensus statement [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991]. This working group identified a range of risk factors for CV disease and proposed that intervention at any point within the continuum has the ability to modify the progression of CV disease [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991; Ferrario and Strawn, 2006].

The first stage in the CV continuum is the occurrence of risk factors that predispose to tissue injury, such as hypertension, increased low density lipoproteins (LDLs) and diabetes. Subsequent steps in the continuum see the progressive advance of heart and vascular disease as exemplified by the development of atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease leading to left ventricular dysfunction. If unchecked, this leads to clinical events such as myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and cardiac remodelling. Failure to effectively treat the patient at any of these stages in the continuum results in ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis followed by congestive heart failure or cerebrovascular disease. Ultimately, the patient develops endstage heart disease, brain damage and dementia, resulting in cerebro/CV death [Dzau and Braunwald, 1991].

The association between risk factors and the development of CV disease was investigated in the large-scale standardized, case-control INTERHEART study, which was conducted in 52 countries [Yusuf et al. 2004]. In the INTERHEART study, 15,152 patients admitted with symptoms of acute MI were compared with 14,820 age-matched controls [Yusuf et al. 2004]. This study revealed that 90% of the population attributable risk (PAR) for acute MI resulted from the presence of at least one of 9 independent risk factors (tobacco smoking, elevated apolipoprotein A, hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, psychosocial factors, low fruit and vegetable intake, low physical activity and alcohol consumption). The effect of these risk factors was shown to be additive, with a greater risk of CV events occurring as the number of risk factors increased. For example, the combination of current smoking, hypertension and diabetes was shown to account for 53% of the PAR [Yusuf et al. 2004].

The mechanisms of action underlying the progression of the CV continuum have been attributed to the actions of Ang II, with the oxidative stress caused by the presence of risk factors producing an inflammatory response that favours a high expression of Ang II [Unger, 2002; Dell’Italia, 2011]. Acting through the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor, Ang II stimulates vascular remodelling, leading to increased blood pressure (BP) and contributing to chronic disease pathology by promoting vascular growth and proliferation, endothelial dysfunction and cellular damage due to increased accumulation of radical oxygen species [Dell’Italia, 2011]. Ang II is involved at every step in the process of the progression from atherosclerosis, coronary atherothrombotic disease, MI, remodelling and heart failure to endstage heart disease [Dell’Italia, 2011]. Ang II has also been shown to exert a wide variety of deleterious effects that are mediated either directly, or through a number of signal-transduction pathways that result in cellular proliferation, increased oxidative stress and reduced nitric oxide levels [Morawietz et al. 2006]. Earlier suggestions of a link between the RAS and activation of immune mechanisms [Chatelain and Ferrario, 1978; Chatelain et al. 1980] leading to cardiac and vascular damage have been demonstrated through the provocative findings that Ang II is a modulator of immune mechanisms in hypertension [Harrison et al. 2011].

Cardiac remodelling

A meeting held in 1998, the International Forum on Cardiac Remodelling, aimed to discuss the basic mechanisms of cardiac remodelling and to provide a consensus on key concepts and definitions underlying this process [Cohn et al. 2000]. According to Cohn and colleagues, cardiac remodelling can be defined as ‘genome expression, molecular, cellular and interstitial changes that are manifested clinically as changes in size, shape and function of the heart after cardiac injury’ [Cohn et al. 2000]. Cardiac remodelling has been linked to a worsening of cardiac function and is one of the mechanisms that perpetuate CV disease progression, making it a potential therapeutic target for intervention [Cohn et al. 2000].

The left ventricular hypertrophy associated with cardiac remodelling normally begins within the first few hours after a MI [Cohn et al. 2000]. A number of factors can influence the speed of cardiac remodelling, including hemodynamic load and neurohormonal activation [Cohn et al. 2000]. In addition, ischaemia, cellular necrosis and apoptosis may play a role [Cohn et al. 2000]. It is a physiological and pathological condition that may occur following MI, pressure overload (e.g. aortic stenosis, hypertension), inflammatory heart muscle disease (i.e. myocarditis), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or volume overload due to valvular regurgitation [Cohn et al. 2000]. The myocyte is the principal cardiac cell involved in the remodelling process, altering the shape of the heart, making it more spherical and less elliptical, increasing left ventricular volume and ventricular mass [Cohn et al. 2000]. Other components believed to be involved in cardiac remodelling include the interstitium, fibroblasts, collagen and coronary vasculature [Cohn et al. 2000].

Although the exact mechanisms underlying all the pathways and cells involved in cardiac remodelling have not been fully elucidated, the following hypothesis has been proposed by the members of the International Forum on Cardiac Remodelling: stretch within myocytes results in local noradrenaline activity together with angiotensin and endothelin release [Cohn et al. 2000]. This in turn stimulates myocyte hypertrophy due to the expression of altered proteins and results in a further deterioration in cardiac function. Increased neurohormonal activation, together with increased aldosterone and cytokine activation, stimulates collagen synthesis leading to fibrosis and remodelling of the extracellular matrix [Cohn et al. 2000]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that therapeutic agents such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), Ang II receptor blockers (ARBs) and beta-blockers can modify the process of cardiac remodelling in addition to their other clinically relevant benefits in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with CV disease [Verdecchia et al. 1998; Cohn et al. 2000; Dell’Italia, 2011]. Taken together, these findings implicate the RAS in the mechanisms underlying cardiac remodelling.

Effects of Ang II

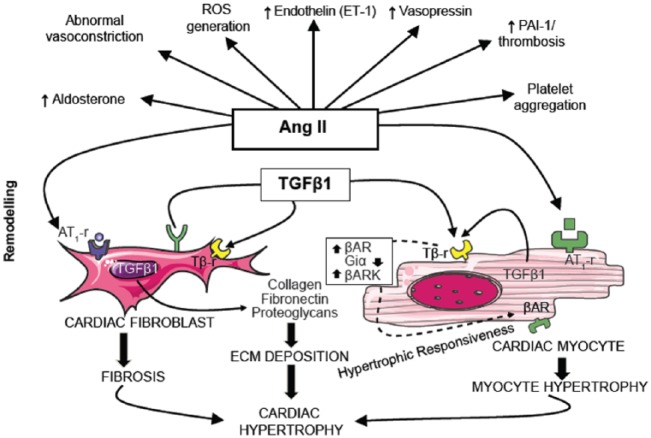

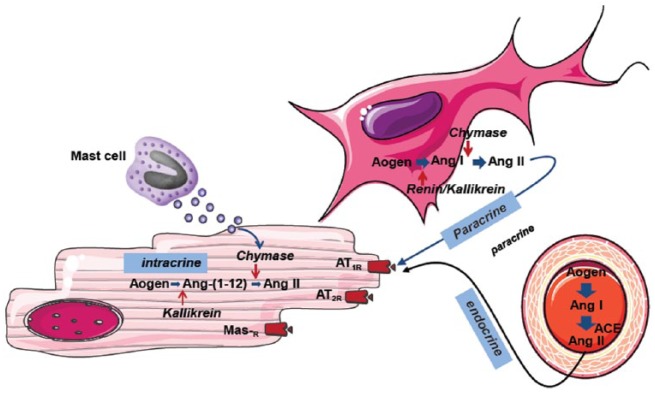

The key stage in the effector mechanisms of the RAS is the binding of Ang II to AT1 receptors. This initiates a signal transduction cascade that results in enhanced collagen synthesis by cardiac fibroblasts, causing fibrosis and myocyte hypertrophy, both of which underlie the development of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 1) [Krenning et al. 2010]. Ang II has been found to display paracrine, intracrine and endocrine influences on cellular signalling pathways (Figure 2). Intracrine actions include the ability of intracellular renin, if present, to alter the electrical properties of the cardiac cell membrane by shortening of the action potential and reducing the refractoriness period [De Mello, 2013]. These changes occur due to an increase in the total potassium current within the cell, which results in concomitant changes in heart excitability. It has been proposed that these intracrine effects of Ang II might be of particular importance during pathological conditions such as MI, when heart excitability is already enhanced [De Mello, 2013]. Ang II has also been shown to increase the percentage and velocity of myocyte shortening, increase the velocity of myocyte re-lengthening and increase peak systolic transient calcium levels [Zhou et al. 2015].

Figure 1.

Angiotensin II drives the mechanisms underlying cardiac remodelling.

Ang II, angiotensin II; AT1-r, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; βAR, β-adrenergic receptor; βARK, β-adrenergic receptor kinase; ECM, extracellular matrix; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Tβ-r, TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1.

Figure 2.

Intracrine, paracrine and endocrine signalling mechanisms of angiotensin II.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; Ang, angiotensin; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2R, angiotensin II type 2 receptor; Mas-R, Mas receptor.

A report presenting hormonal data obtained during the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) [The Consensus Trial Study Group, 1987] evaluated the relationship between hormonal activation in heart failure and prognosis; an association between upregulation of ACE and the evolution of heart failure was noted [Swedberg et al. 1990]. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted by Hirsch and colleagues, who noted that the renal effects of ACE may play a role in heart failure [Hirsch et al. 1992]. In contrast, the limited ability of ACE-Is in heart failure progression and cardiac Ang II suppression may be related to the more prominent role of chymase in human Ang II production from angiotensin I (Ang I) [Zablocki and Sadoshima, 2010; Ferrario et al. 2014]. Thus, it is possible that an ‘escape phenomenon’ occurs with chronic Ang II suppression which allows Ang II to return to normal levels [Zablocki and Sadoshima, 2010].

Inhibition of the RAS

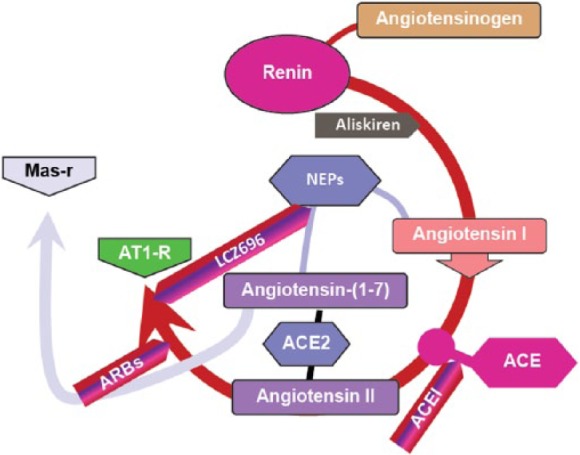

In a transgenic rat model of renin-dependent hypertension, direct renin inhibition by means of AT1 receptor blockade has been shown to reduce both cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac remodelling [Whaley-Connell et al. 2013]. Interestingly, a reduction in interstitial cardiac fibrosis was also observed and it is thought that this may contribute to the observed reduction in hypertrophy [Whaley-Connell et al. 2013]. Different anti-RAS approaches act at different points within the system (Figure 3). For example, the direct renin inhibitor, aliskiren, acts early in the RAS pathway to block the hydrolysis of angiotensinogen to Ang I by the enzyme renin [Pilz et al. 2005; Ferrario, 2010; Esteras et al. 2015]. Further down the RAS pathway, ACE-Is prevent the hydrolysis of Ang I to the key effector of the pathway, Ang II [Esteras et al. 2015]. The effector actions of Ang II are inhibited by ARBs, which block the binding of Ang II to AT1 receptors [Esteras et al. 2015]. In addition, a novel combination of an AT1 receptor antagonist with an inhibitor of cardiac atrial natriuretic peptide metabolism within a single entity has shown superior efficacy over ACE-Is, and so may become a major pillar of future heart failure treatment approaches [McMurray et al. 2014]. Valsartan/sacubitril (previously known as LCZ696) is an example of an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor containing an ARB as well as a neprilysin inhibitor that acts to increase circulating levels of natriuretic peptides [Segura et al. 2013]. Another dual inhibitor, omapatrilat, combined ACE and neprilysin inhibition, but use of this combination has been associated with increased levels of angioedema [Buggey et al. 2015].

Figure 3.

Target sites for the therapeutic inhibition of the renin–angiotensin system.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ATI-R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; Mas-R, Mas receptor.

It has been suggested that treatment with antihypertensive agents may result in regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, with different drug classes exhibiting different degrees of hypertrophy regression [Schmieder et al. 1996]. A meta-analysis of 39 randomized controlled trials examined the ability of various antihypertensive agents to reduce left ventricular hypertrophy. This analysis demonstrated that greater reductions in BP were associated with a more marked decrease in left ventricular hypertrophy, as was a longer duration of treatment [Schmieder et al. 1996]. The greatest decrease in left ventricular mass and wall thickness was observed with ACE-Is (13%) compared with reductions of 9% with calcium channel blockers, 7% with diuretics and 6% with beta-blockers [Schmieder et al. 1996]. However, despite the efficacy of ACE inhibition in terms of BP lowering and interruption of the CV continuum, there is a growing body of evidence that these agents may not produce a sustained inhibition of Ang II synthesis [Garg and Yusuf, 1995; Ferrario, 2010, Ferrario et al. 2014]. Rather, an escape phenomenon which permits synthesis of Ang II via an alternative pathway may ultimately allow the RAS to overcome the effects of ACE-Is [Garg and Yusuf, 1995; Ferrario, 2010; Ferrario et al. 2014]. In addition, Ang II intracrine actions will not be affected by either ACE-Is or ARBs as these drugs act preferentially at the level of the cell membrane.

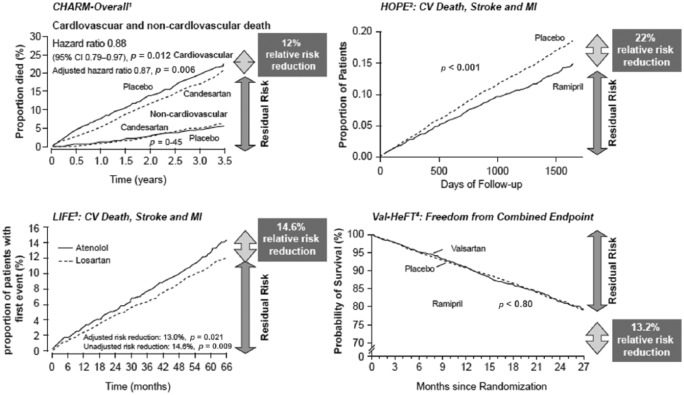

Clinical studies investigating the inhibition of the RAS

Although clinical trial data indicate that ACE-I and ARB therapies provide a significant benefit when compared with placebo in terms of endpoints such as MI, stroke, congestive heart failure, hospitalization for CV events and CV-related mortality, the incidence of these events remains high [The Consensus Trial Study Group, 1987; SOLVD Investigators, 1991; Yusuf et al. 2000; Dahlof et al. 2002; Granger et al. 2003]. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Trial assessed the role of the ACE-I, ramipril, in patients who did not have left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure, but nonetheless were considered to be at high risk for CV events [Yusuf et al. 2000]. Treatment with ramipril reduced the rate of death from CV causes when compared with placebo (6.1% versus 8.1%, respectively). A reduction in the relative risk of MI, stroke, cardiac arrest and heart failure was also observed in those patients who received ramipril [Yusuf et al. 2000]. However, 14% of the patients in the treatment group still experienced a CV-related event compared with 17.8% of placebo-treated patients [Yusuf et al. 2000]. In other words, the residual risk for events was substantially higher than the benefit.

The Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trial compared the ACE-I enalapril with placebo in patients with congestive heart failure who were receiving conventional treatment [SOLVD Investigators, 1991]. The addition of enalapril to conventional treatment significantly reduced mortality and hospitalization for heart failure in these patients. SOLVD demonstrated that 35.2% (452) of patients who were receiving enalapril died compared with 39.7% (510) of placebo-treated patients. Therefore, although the addition of this treatment added benefit, a considerable number of enalapril-treated patients did not survive [SOLVD Investigators, 1991]. Similarly, in the CHARM-Alternative (Candesartan in Heart failure – Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) trial, heart failure patients with ACE-I intolerance were randomised to receive either placebo or the ARB candesartan (target dose, 32 mg per day) [Pfeffer et al. 2003b]. During a median follow up of 33.7 months, hospitalization or CV-related death was reported in 33% (n = 334) of candesartan patients versus 40% (n = 406) of placebo patients. As in the SOLVD study, although active treatment offered clinical benefit when compared with placebo, a marked number of patients did not survive, or experienced an unfavourable outcome [Granger et al. 2003]. The Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE) compared the ARB losartan with the beta-blocker atenolol in 9,193 individuals with essential hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy [Dahlof et al. 2002]. This study noted fewer deaths and a lower rate of CV morbidity in those patients who received losartan compared with atenolol. However, there were still 204 deaths amongst patients in the losartan arm of the LIFE study [Dahlof et al. 2002]. It should be noted, however, that two important clinical trials have demonstrated significant benefits of the ARB valsartan in reducing the risk of hospital admissions for worsening heart failure, and death [Cohn and Tognoni, 2001] and evolution post-MI [Pfeffer et al. 2003a].

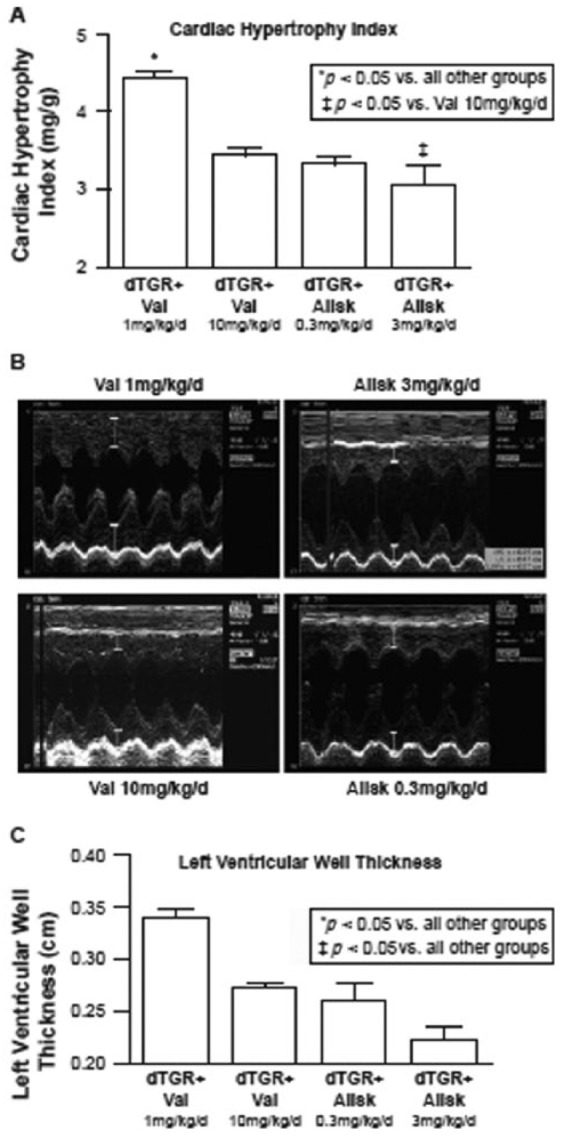

As previously discussed, cardiac tissue hypertrophy is indicative of cardiac damage. Pilz and colleagues [Pilz et al. 2005] examined the degree of cardiac hypertrophy occurring during treatment with antihypertensive agents in an animal model of hypertension using echocardiography to measure left ventricular wall thickness and cardiac hypertrophy index (Figure 4). The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that the direct renin inhibitor, aliskiren, and the ARB, valsartan, possess the ability to ameliorate the cardiac and renal damage observed in this animal model. Compared with untreated animals, both aliskiren and valsartan reduced systolic BP and albuminuria, and prevented cardiac hypertrophy [Pilz et al. 2005]. Clinical data have also demonstrated that aliskiren, at a dose of 300 mg, was as effective as the ARB losartan (100 mg) in promoting left ventricular mass regression in 465 patients with hypertension and increased ventricular wall thickness [Solomon et al. 2009]. Reduction in left ventricular mass in those who received aliskiren in combination with losartan was not significantly different from those who received losartan monotherapy [Solomon et al. 2009]. Thus, direct renin inhibition appears to be as effective as ARB treatment in attenuating the cardiac hypertrophy observed in hypertensive patients.

Figure 4.

Comparative effects of valsartan (Val) and aliskiren (Allsk) in double transgenic rats (dTGR+) in terms of cardiac hypertrophic index (A, top panel), M-mode echocardiography (B, middle panel) and left ventricular dimensions (C, bottom panel). Aliskiren has been shown to prevent left ventricular hypertrophy and reduce left ventricular mass in an animal model of hypertension [Pilz et al. 2005].

Allak, aliskiren; TGR, double transgenic rats; Val, valsartan.

It is therefore apparent, that despite adequate treatment of hypertension, a residual risk of morbidity and mortality remains in those patients who are treated with either ACE-Is or ARBs. Several clinical studies, including CHARM, HOPE, LIFE and Val-HeFT have demonstrated considerable mortality rates in patients receiving anti-RAS medication (Figure 5) [Yusuf et al. 2000; Cohn and Tognoni, 2001; Dahlof et al. 2002; Pfeffer et al. 2003b]. Moreover, studies have failed to produce clear evidence for the benefit of any particular drug class or classes that would support their recommendation for the treatment of either older or younger adults [Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment; Turnbull et al. 2008]. Thus, despite evidence for the involvement of Ang II in the pathogenesis of CV disease, the long-term use of RAS inhibitors in the treatment of patients with CV disease has not proved as effective as originally hoped, due to a partial failure to suppress the actions of Ang II within the cell itself [Ferrario et al. 2005].

Figure 5.

Plots of the Kaplan–Meier for cardiovascular end-points of four major trials comparing active treatment to corresponding placebos. Despite the benefits of ACE-Is and ARBs in terms of reducing hypertension, a residual risk of morbidity and mortality remains. Superscripts on the named-trials denote corresponding citations [1Pfeffer et al. 2003b; 2Yusuf et al. 2000; 3Dahlöf et al. 2002; 4Cohn and Tognoni, 2001

ACE-Is, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction.

Improved understanding of the RAS has presented novel targets

The observed loss of efficacy of ACE-Is over time has resulted in the hypothesis that an escape phenomenon provides an alternative pathway for the synthesis of Ang II [Garg and Yusuf, 1995; Ferrario, 2010; Ferrario et al. 2014]. Angiotensin-(1-12) (Ang-(1-12)) is a novel 12 amino acid peptide substrate that was initially isolated from the rat intestine [Nagata et al. 2006]. In the presence of the Mast cell protease, chymase, Ang-1(1-12) is converted directly into Ang II in humans [Ahmad et al. 2011].

Investigations have shown that Ang-(1-12) is abundant in a wide range of organs and tissues including the small intestine, spleen, kidneys, heart and liver. Furthermore, it demonstrated the ability to constrict aortic strips in vitro and increase BP in rats, effects which were abolished in the presence of either the ACE-I captopril or the ARB candesartan [Nagata et al. 2006]. Following on from these findings, studies conducted by our research group at Wake Forest University School of Medicine have highlighted differences between humans and rodents regarding the enzymatic pathway responsible for the metabolism of Ang-(1-12) [Ferrario et al. 2014]. In addition, Ang-(1-12) has been shown to function as a non-renin alternative precursor for the local tissue production of Ang II, which facilitates intracrine or paracrine RAS functions [Jessup et al. 2008; Ferrario et al. 2014].

Targeting of Ang-(1-12)

Characterization of the expression and localization of Ang-(1-12) has shown that it is predominantly found in ventricular myocytes and the proximal, distal and collecting renal tubules within the deep cortical and outer medullary zones [Jessup et al. 2008]. Moreover, comparisons of the expression of Ang-(1-12) in hypertensive rats and normotensive rats revealed significantly higher levels of Ang-(1-12) in the heart and significantly lower levels in the kidneys of hypertensive rats [Jessup et al. 2008]. The metabolism of Ang-(1-12) has been investigated in plasma membranes isolated from human atrial appendage tissue [Ahmad et al. 2011]. In the absence of any RAS inhibitor, Ang-(1-12) was converted into Ang I, Ang II, angiotensin-(1-7) and angiotensin-(1-4), with the primary metabolism occurring via chymase to produce Ang II. In parallel to these findings, Ahmad and colleagues also used immunohistochemistry to demonstrate significant chymase levels primarily localized within the atrial cardiac myocytes [Ahmad et al. 2011].

Cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion injury occurs as the consequence of an acute increase in oxidative and inflammatory stress during reperfusion. The outcome of this injury is the death of cardiac myocytes. Mast cells normally exist in an intact form within the myocardium, but become activated releasing enzymes, such as chymase, in response to acute stress. Following ischaemia/reperfusion cardiac injury, degranulation of mast cell contents into the interstitium is common [Zheng et al. 2014]. Using a preclinical model, Zheng and colleagues investigated the role of the Mast cell protease, chymase, in cardiomyocyte injury following ischaemia/reperfusion cardiac injury. Pretreatment with a specific oral chymase inhibitor significantly attenuated loss of laminin, focal adhesion complex disruption and release of troponin I into the circulation. Further immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated a high level of chymase within cardiomyocytes after ischaemia/reperfusion injury [Zheng et al. 2014]. Taken together, these findings provide evidence for a secondary pathway within the RAS that can enable the system to overcome blockade with traditional ACE-Is to continue to produce Ang II, thus permitting the effects of the RAS on the CV continuum to continue unchecked.

Conclusion

Research over the last few years has revealed that CV disease exists as a continuum, with treatment at any point within this process capable of modifying disease progression. Several studies have shown that left ventricular hypertrophy is an independent risk factor for mortality from CV disease. Moreover, this can be corrected by the use of treatments to inhibit the RAS, which will in turn, modulate the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and so interrupt the CV continuum. However, escape mechanisms mean that commonly used RAS inhibitors do not fully prevent the formation and actions of intracellular Ang II, which has itself been implicated in the process of cardiac remodelling. These escape mechanisms represent a novel intracrine pathway, whereby chymase is able to act within myocytes to convert angiotensin-(1-12) into Ang II. Therefore, new therapeutic approaches that target this novel pathway are required in order to reduce Ang II formation and so provide patients with further benefits from a more complete blockade of the RAS.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Sarah Birch of Novartis Ireland Ltd., Dublin, Ireland.

Footnotes

Funding: The author acknowledges that his studies regarding novel angiotensins is supported by a grant (2P01 HL-051952) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Pressure of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement: The author declares no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

References

- Ahmad S., Simmons T., Varagic J., Moniwa N., Chappell M., Ferrario C. (2011) Chymase-dependent generation of angiotensin II from angiotensin-(1-12) in human atrial tissue. PLoS One 6: e28501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggey J., Mentz R., Devore A., Velazquez E. (2015) Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition in heart failure: mechanistic action and clinical impact. J Card Fail 21: 741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain R., Ferrario C. (1978) Biphasic changes in thymus structure during evolving renal hypertension. Clin Sci Mol Med 55: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain R., Vessey A., Ferrario C. (1980) Lymphoid alterations and impaired T lymphocyte reactivity in experimental renal hypertension. J Lab Clin Med 95: 737–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J., Ferrari R., Sharpe N. (2000) Cardiac remodeling – concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J., Tognoni G. (2001) A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 345: 1667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlof B., Devereux R., Kjeldsen S., Julius S., Beevers G., De Faire U., et al. (2002) Cardiovascular Morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 359: 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello W. (2013) Intracellular renin alters the electrical properties of the intact heart ventricle of adult Sprague–Dawley rats. Regul Pept 181: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Italia L. (2011) Translational success stories: angiotensin receptor 1 antagonists in heart failure. Circ Res 109: 437–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzau V., Braunwald E. (1991) Resolved and unresolved issues in the prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease: a workshop consensus statement. Am Heart J 121: 1244–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteras R., Perez-Gomez M., Rodriguez-Osorio L., Ortiz A., Fernandez-Fernandez B. (2015) Combination use of medicines from two classes of renin–angiotensin system blocking agents: risk of hyperkalemia, hypotension, and impaired renal function. Ther Adv Drug Saf 6: 166–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario C. (2010) Addressing the theoretical and clinical advantages of combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system: antihypertensive effects and benefits beyond BP control. Life Sci 86: 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario C., Ahmad S., Nagata S., Simington S., Varagic J., Kon N., et al. (2014) An evolving story of angiotensin-II-forming pathways in rodents and humans. Clin Sci 126: 461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario C., Jessup J., Chappell M., Averill D., Brosnihan K., Tallant E., et al. (2005) Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 111: 2605–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario C., Strawn W. (2006) Role of the Renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system and proinflammatory mediators in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 98: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R., Yusuf S. (1995) Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. JAMA 273: 1450–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger C., McMurray J., Yusuf S., Held P., Michelson E., Olofsson B., et al. (2003) Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet 362: 772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D., Guzik T., Lob H., Madhur M., Marvar P., Thabet S., et al. (2011) Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension 57: 132–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch A., Talsness C., Smith A., Schunkert H., Ingelfinger J., Dzau V. (1992) Differential effects of captopril and enalapril on tissue renin–angiotensin systems in experimental heart failure. Circulation 86: 1566–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup J., Trask A., Chappell M., Nagata S., Kato J., Kitamura K., et al. (2008) Localization of the novel angiotensin peptide, angiotensin-(1-12), in heart and kidney of hypertensive and normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2614–H2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenning G., Zeisberg E., Kalluri R. (2010) The origin of fibroblasts and mechanism of cardiac fibrosis. J Cell Physiol 225: 631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray J., Packer M., Desai A., Gong J., Lefkowitz M., Rizkala A., et al. (2014) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 371: 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawietz H., Rohrbach S., Rueckschloss U., Schellenberger E., Hakim K., Zerkowski H., et al. (2006) Increased cardiac endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. Eur J Clin Invest 36: 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S., Kato J., Sasaki K., Minamino N., Eto T., Kitamura K. (2006) Isolation and identification of proangiotensin-12, a possible component of the renin–angiotensin system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 350: 1026–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer M., McMurray J., Velazquez E., Rouleau J., Kober L., Maggioni A., et al. (2003a) Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 349: 1893–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer M., Swedberg K., Granger C., Held P., McMurray J., Michelson E., et al. (2003b) Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 362: 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz B., Shagdarsuren E., Wellner M., Fiebeler A., Dechend R., Gratze P., et al. (2005) Aliskiren, a human renin inhibitor, ameliorates cardiac and renal damage in double-transgenic rats. Hypertension 46: 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder R., Martus P., Klingbeil A. (1996) Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. A meta-analysis of randomized double-blind studies. JAMA 275: 1507–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura J., Salazar J., Ruilope L. (2013) Dual neurohormonal intervention in CV disease: angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 22: 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S., Appelbaum E., Manning W., Verma A., Berglund T., Lukashevich V., et al. (2009) Effect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren, the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan, or both on left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 119: 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLVD Investigators (1991) Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 325: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg K., Eneroth P., Kjekshus J., Wilhelmsen L. (1990) Hormones regulating cardiovascular function in patients with severe congestive heart failure and their relation to mortality. Circulation 82: 1730–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Consensus Trial Study Group (1987) Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 316: 1429–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull F., Neal B., Ninomiya T., Algert C., Arima H., Barzi F., et al. (2008) Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br Med J 336: 1121–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger T. (2002) The role of the renin–angiotensin system in the development of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 89: 3A–9A; discussion 10A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecchia P., Schillaci G., Borgioni C., Ciucci A., Gattobigio R., Zampi I., et al. (1998) Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation 97: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley-Connell A., Habibi J., Rehmer N., Ardhanari S., Hayden M., Pulakat L., et al. (2013) Renin inhibition and AT1R blockade improve metabolic signaling, oxidant stress and myocardial tissue remodeling. Metabolism 62: 861–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Hawken S., Ôunpuu S., Dans T., Avezum A., Lanas F., et al. (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the Interheart Study): case-control study. Lancet 364: 937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., Bosch J., Davies R., Dagenais G. (2000) Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. Engl J Med 342: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablocki D., Sadoshima J. (2010) The one-two punch: knocking out angiotensin II in the heart. J Clin Invest 120: 1028–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Wei C., Hase N., Shi K., Killingsworth C., Litovsky S., et al. (2014) Chymase Mediates injury and mitochondrial damage in cardiomyocytes during acute ischemia/reperfusion in the dog. PLoS One 9: e94732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Cheng C., Li T., Ferrario C., Cheng H. (2015) Modulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ current by angiotensin-(1-7): normal versus heart failure. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 9: 342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]