Abstract

BACKGROUND

Individuals whose families meet the Amsterdam II clinical criteria for Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) are recommended to be referred for genetic counselling and to have colonoscopic screening every 1-2 years.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the uptake and knowledge of guideline-based genetic counseling and colonoscopic screening in unaffected members of families who meet Amsterdam II criteria and their treating endoscopists.

METHODS

Participants in the Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP) who met Amsterdam II criteria were surveyed regarding their knowledge of risk appropriate guidelines for genetic counseling and colonoscopy screening. Endoscopy/pathology reports were obtained from patients screened during the study to determine the follow-up recommendations made by their endoscopists. Survey responses were compared using the Fisher's Exact and Chi-square test. Concordance in participant/provider-reported surveillance interval was assessed using the kappa statistic.

RESULTS

Of the 165 participants, the majority (98%) agreed that genetics and family history are important predictors of CRC and 63% had heard of genetic testing for CRC, though only 31% reported being advised to undergo genetic counseling by their doctor and only 7% had undergone genetic testing. Only 26% of participants reported that they thought they should have colonoscopy every 1-2 years and 30% of endoscopists for these participants recommended 1 to 2 year follow up colonoscopy. There was a 65% concordance (weighted kappa 0.42, 95% CI 0.24-0.61) between endoscopist recommendations and participant reports regarding screening intervals.

CONCLUSIONS

A minority of individuals meeting Amsterdam II criteria in this series have had genetic testing and reported accurate knowledge of risk appropriate screening, and only a small percentage of their endoscopists provided them with the appropriate screening recommendations. There was moderate concordance between endoscopist recommendations and participant knowledge suggesting that future educational interventions need to target both healthcare providers and their patients.

Keywords: Lynch Syndrome, Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer, Colonoscopy, Screening, Genetic Counseling

Introduction

Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder accounting for approximately 2-4% of all colorectal cancers (CRCs) and is associated with a 50-80% lifetime risk of developing CRC.1 The Amsterdam II2 family history criteria for Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) are used to identify individuals who are at increased risk for Lynch Syndrome. These criteria include: three biological relatives with CRC or another Lynch-associated cancer (endometrial, ovarian, upper urinary tract, small bowel) who are linked through a first-degree relative; at least two consecutive generations affected; and one cancer diagnosis under the age of 50.

Professional society guidelines3-8 recommend offering genetic counseling to all individuals who meet Amsterdam II criteria. According to these guidelines, Lynch syndrome mutation carriers and age-eligible individuals who meet Amsterdam II criteria who have not undergone genetic testing should undergo colonoscopy every one to two years starting at age 20-25.

Although aggressive screening in Lynch Syndrome has shown to reduce CRC incidence and mortality,9 individuals at risk for Lynch Syndrome are grossly under-recognized. Hampel et al10 estimated that only approximately 10,000 of the projected 830,000 individuals (1.2%) in the United States with Lynch Syndrome are aware of their mutation status. Some possible reasons for failure to identify Lynch Syndrome families include incomplete ascertainment of multi-generation family history data, lack of recognition that an individual meets Amsterdam II criteria, limited sensitivity of Amsterdam II criteria for diagnosing Lynch Syndrome and cumbersome predictive models used clinically to assess CRC risk.

Even when Lynch Syndrome is suspected or confirmed, the reported compliance rates for CRC screening are widely variable (53-100%).11-16 These projections are likely overestimates as most studies included highly selected patient populations from genetics clinics and are often considered “compliant” if they participate in a single screening test or who have “ever been screened.” A lack of knowledge regarding recommended screening guidelines among patients as well as providers has been identified as potential barriers to appropriate guideline-based screening.17, 18

There is limited data regarding knowledge and uptake of genetic counseling and colonoscopic screening recommendations for CRC-unaffected individuals who meet Amsterdam II criteria, especially those individuals who may not be aware that they are at risk of Lynch Syndrome. Further, little is known about what screening intervals endoscopists who care for these patients recommend and how these compare with what patients understand. We hypothesized that there is poor knowledge and uptake of genetic counseling and colonoscopic screening among patients unaffected by CRC who meet Amsterdam II criteria and their providers and that this is more pronounced in persons identified in the general population as compared to those whose families have sought care at high risk cancer clinics.

The aims of this study were (1) to evaluate the knowledge and uptake of genetic counselling and testing and the knowledge of risk-appropriate colonoscopic screening among CRC-unaffected members of families who meet Amsterdam II criteria recruited from both high-risk cancer clinics as well as population-based registries, (2) to evaluate the proportion of endoscopists whose follow up recommendations were consistent with current guidelines for individuals meeting Amsterdam II criteria and (3) compare endoscopist and patient understanding of appropriate screening intervals.

Methods

Study Design

Study participants were enrolled in the Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP), a randomized controlled trial19 designed with the primary aim of promoting colonoscopy adherence in members of high-risk CRC families; details of the FHPP study design have been previously published.19 Briefly, first degree family members unaffected by CRC were recruited from two national cancer registries: the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR) and the Cancer Genetics Network (CGN),20 which included individuals identified by high-risk cancer clinics as well as from population-based cancer registries. These registries collected detailed, three-generation family histories. CRC-unaffected family members identified through these registries were sent a general newsletter regarding familial cancer risk and were invited to participate in FHPP. For the FHPP trial, these CRC-unaffected participants were randomized to receive either an intensive tailored telephone and mailed counseling intervention (providing risk-specific, guideline-based colonoscopic screening recommendations of colonoscopy every 1-2 years for Amsterdam II participants) or to a control group that was mailed general information about the importance of cancer screening, but no specific risk-based recommendations. The present analysis is restricted to the FHPP participants whose family met Amsterdam II criteria (based on the three generation family history obtained from the CFR and CGN).

All participants completed a baseline questionnaire prior to randomization and a follow-up questionnaire at 24 months. The baseline questionnaire evaluated participants’ knowledge and uptake of genetic testing and, knowledge of risk appropriate colonoscopy screening intervals based on their personal risk. The 24 month follow-up questionnaire similarly assessed knowledge of recommended colonoscopy screening intervals as well as adherence to colonoscopy screening during the study period.

Upon completion of the 24 month study period, a supplemental questionnaire was mailed to all participants who completed the FHPP study (2008-2009) and included additional questions about how genetic testing was discussed between patients and providers and barriers to genetic testing.

The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

FHPP participants (n=632) were recruited from nine CCFR and three CGN registry sites in the United States from 2004 to 2006, and were unaffected by CRC, at least 21 years of age and English speaking. For this analysis, we included only those FHPP participants whose family met the Amsterdam II criteria (n=165).

Study Aims

Knowledge and Uptake of Genetic Testing

The baseline questionnaire asked the following questions regarding uptake of genetic counseling:

“Have you ever heard of genetic testing for colon cancer,” “Have any of your relatives had genetic testing,” “if yes, did any of them test positive,” “have you ever been advised to undergo genetic testing for colon cancer,” “have you ever had genetic testing for colon cancer” and “if yes, did you test positive?”

The supplemental questionnaire asked the following questions regarding genetic counseling:

“Have you ever discussed genetic testing for colon cancer with your provider, if so, who raised the issue (I did, my doctor, other healthcare provider),” “have you ever been advised to consider genetic testing for colon cancer, if so, who advised you,” and “if you were advised to have genetic testing and did not, why did you choose not to be tested?”

Knowledge and Uptake of Colonoscopic Screening

Participant knowledge of colorectal cancer screening recommendations (based on guidelines for their level of risk) was evaluated by the following question asked at baseline and 24 months after the intervention: “How often should you have a colonoscopy performed? (responses: every 1-2 years; every 2-5 years, every 5-9 years; every 10 years or more).” A response of ‘every 1-2 years’ was considered to be a correct answer.

Adherence to colonoscopy screening was evaluated during follow-up as previously reported.21 Participants who underwent colonoscopy at any time during the study period were asked to sign a medical release of information so that endoscopy reports, pathology reports and medical chart documentation regarding endoscopy findings and follow up recommendations could be obtained. For this analysis, endoscopist screening interval recommendations were determined based on review of the endoscopy/pathology reports and documentation in the patient chart.

Concordance between participant and endoscopist perceived appropriate screening interval was evaluated by comparing individual endoscopist recommendations and participant responses as reported on the 24 month follow-up questionnaire.

Data Management & Statistical Analysis

All data was analyzed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, North Carolina). Participant responses regarding knowledge of genetic counseling/testing and risk-appropriate screening intervals (dichotomous outcomes) were compared overall and according to participant recruitment source (clinic based vs population based) using the Chi squared or Fisher's Exact test as appropriate. Concordance in participant-reported and endoscopist-reported recommendation of colonoscopy screening interval is reported as the proportion of responses in agreement and was assessed using the kappa statistic.

Results

A total of 165 consenting participants from families who met Amsterdam II criteria were enrolled in FHPP, completed the baseline questionnaire and were included in this study. There was a 90% response rate for the 24 month follow up questionnaire (n=149) and a 55.2% response rate for the supplemental questionnaire (n=91). There were no differences in the participants who completed the follow-up questionnaire and supplemental questionnaire in terms of baseline characteristics, intervention group or whether they were adherent to colonoscopy screening during the study.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 165 participants included in this analysis are shown in Table 1. Approximately 50 percent of participants were women, the majority were 50 years of age or older, Caucasian, had health insurance, a regular doctor and incomes over $45,000. A little more than half of participants (57%) were recruited into the FHPP study through a family member who was a patient in a high-risk cancer clinic vs. 43% who were recruited through a family member identified by population-based cancer registries.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 165 FHPP participants from families meeting Amsterdam II criteria.

| (N, %) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | 81 (49.1%) |

| F | 84 (50.9%) | |

| Age | < 40 | 12 (7.3%) |

| 40-49 | 33 (20.0%) | |

| 50-59 | 60 (36.4%) | |

| 60-69 | 38 (23.0%) | |

| 70-79 | 22 (13.3%) | |

| Race | White | 155 (93.9%) |

| Asian | 2 (1.2%) | |

| African American/Black | 8 (4.9%) | |

| Income | > 70 K | 65 (39.4%) |

| 45 K-69,999 | 45 (27.3%) | |

| 30 K-44,999 | 23 (13.9%) | |

| 15 K-29,999 | 12 (7.3%) | |

| < 14,999 | 7 (4.2%) | |

| Don't Know/Prefer not to answer | 13 (7.9%) | |

| Education | Post College | 29 (17.6%) |

| College Graduate | 49 (29.7%) | |

| Some college or technical school | 50 (30.3%) | |

| High school/GED | 30 (18.2%) | |

| Less than High School | 6 (3.6%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Insurance Status | Yes | 158 (95.8%) |

| No | 6 (3.6%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Regular Doctor | Yes | 152 (92.1%) |

| No | 13 (7.9%) | |

| Recruitment source | High-Risk Clinic Based | 94 (57.0%) |

| Population Based | 71 (43.0%) |

Participant Knowledge & Uptake of Genetic Testing

At baseline, 98 percent (n=162) of participants reported that genetics or having a family history of colorectal cancer was ‘very important’ (n=125, 75.7%) or ‘important’ (n=37, 22.4%) in predicting future risk of colon cancer. Sixty-three percent (n=104) had heard of genetic testing; significantly more recruited from a high-risk clinic than those recruited from a population-based registry [71.3% (n=67) vs. 52.1% (n=37), p=0.015)]. Only 31 percent (n=51) of participants recalled being advised by a medical provider to undergo genetic testing (Table 2).

Table 2.

FHPP Participant knowledge about and uptake of genetic counseling at baseline stratified by recruitment source.

| Baseline Survey Question | Response | Overall n=165 (%) | Population Based n=71 (%) | HR Clinic Based n=94 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you heard of genetic testing? | Yes | 104 (63.0) | 37 (52.1) | 67 (71.3) | 0.0146 |

| Have you been advised to undergo genetic testing? | Yes | 51 (30.9) | 17 (23.9) | 34 (36.2) | 0.1254 |

| Have you undergone genetic testing? | Yes | 12 (7.3) | 3 (4.2) | 9 (9.6) | 0.2363 |

| Do you have a relative who has undergone genetic testing? | Yes | 45 (27.3) | 17 (23.9) | 28 (29.8) | 0.4811 |

At baseline, only 7.3% (n=12) had undergone genetic testing (8 reported testing positive, 4 reported testing negative). Twenty-seven percent (n=45) of the participants reported that a relative had undergone genetic testing and 41.8% (n=69) did not know whether a family member had been tested. Of those with family members who had undergone testing, 40.0% (n=18/45) reported that their family member tested positive, 33.3% (n=15/45) tested negative and 26.7% (n=12/45) did not know results of their family member's testing. There was no significant difference in these responses according to recruitment source (population based vs clinic based).

Of the 91 participants who completed the supplemental questionnaire, 24.2% (n=22) reported having ever discussed genetic testing with their treating physicians; of these, 36% (n=8) had raised the issue themselves, whereas 41% (n=9) reported that their doctor had raised the issue. Thirty-three percent (n=30) of those completing the supplemental questionnaire reported having been advised to undergo genetic testing by a variety of sources (13 from their doctor, 9 from another healthcare provider, 7 from a family member, and one from a friend). Participants cited various barriers to undergoing genetic testing including that they could not afford it or insurance did not cover it (n=10), that they were worried that their insurance company would find out (n=5) or that they have not made up their minds (n=5); however the most common response was that they were not advised to undergo genetic testing (n=29).

Participant Knowledge and Uptake of Colonoscopic Screening

Participants’ knowledge of appropriate colonoscopic screening interval at baseline and 24 months post randomization is shown in Table 3. At baseline, only 21.8% of the participants reported 1-2 years as the appropriate colonoscopy screening interval given their family history of colon cancer with no difference between the participants recruited from a population based registry or those recruited from a high-risk clinic.

Table 3.

FHPP participant knowledge and uptake of colonoscopic screening.

| Question | Response | Overall n=165 (%) | Population Based n=71 (%) | HR Clinic Based n=94 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | |||||

| How frequently should you have a colonoscopy? | Every 1-2 Years | 36 (21.8) | 15 (21.1) | 21 (22.3) | 1.0 |

| Every 2-5 Years | 113 (68.5) | 45 (63.4) | 68 (72.3) | 0.2395 | |

| Every 5-10 Years | 11 (6.7) | 7 (9.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.2094 | |

| > 10 years | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1.0 | |

| I don't know | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1.0 | |

| No Answer | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0.1837 | |

| 24 MONTH FOLLOW-UP | |||||

| How frequently should you have a colonoscopy? | Every 1-2 Years | 42 (25.5) | 9 (12.7) | 33 (35.1) | 0.0011 |

| Every 2-5 Years | 87 (52.7) | 46 (64.8) | 41 (43.6) | 0.0078 | |

| Every 5-10 Years | 16 (9.7) | 7 (9.9) | 9 (9.6) | 1.0 | |

| > 10 years | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 0.1837 | |

| I don't know | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1.0 | |

| No Answer | 16 (9.7) | 6 (8.5) | 10 (10.6) | 0.7922 | |

| Did you have a colonoscopy performed during the study period? | Yes | 95 (57.6) | 35 (49.2) | 60 (63.8) | 0.008 |

At the end of the study (24 months), overall participant knowledge of risk appropriate intervals increased only slightly, to 25.5%. There was a significantly higher percentage of correct risk-based responses in the group recruited from high risk clinics compared to population clinics at 24 months (35.1% vs 12.7%, p=0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in correct risk-based responses when comparing other baseline characteristics. Despite the fact that the telephone intervention strongly emphasized the importance of colonoscopy every 1-2 years, there was no difference in the proportion of participants who reported 1-2 years as the appropriate screening interval between those who received the telephone counseling and tailored follow up letter vs. those who were mailed general screening information (26% vs. 25%, respectively).

Ninety-five (58%) of participants had undergone colonoscopy screening during the two year study period. There were a significantly higher proportion of participants recruited from a high risk clinic that underwent colonoscopy when compared to participants recruited from population-based registries (63.8% vs 49.2%, p=0.008) but there were no significant differences in other baseline characteristics between participants who did and did not have screening.

Endoscopist Recommendations for Colonoscopic Screening Intervals

Colonoscopy and corresponding pathology reports were obtained from 83 of the 95 (87%) participants who reported having a colonoscopy during the study period. The indications for the procedure and follow up recommendations are shown in Table 4. Based on the colonoscopy reports, 20.5% (n=17) listed Lynch Syndrome or HNPCC as the primary indication for the procedure, 72.3% (n=60) listed family history and/or personal history of CRC or polyps and the remaining 8.4% (n=7) listed routine screening, symptoms, or did not document the indication for the procedure.

Table 4.

Colonoscopy indications and follow up recommendations.

| Colonoscopy Results (N=83)a | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indication | Lynch | 17 (20.5%) |

| FH or personal hx polyps | 60 (72.3%) | |

| routine screening | 1 (1.2%) | |

| symptoms | 4 (4.8%) | |

| not documented | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Follow-up interval recommended | 1-2 years | 25 (30.1%) |

| 3-5 years | 42 (50.6%) | |

| Other (flexible sigmoidoscopy, fecal testing) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Not Documented | 14 (16.9%) |

Of the 95 participants who had a colonoscopy during the study period, there were 83 endoscopy/pathology reports available for review.

Only 30.1% (n=25/83) of the participants’ endoscopists recommended repeating colonoscopy at the recommended interval for those that meet Amsterdam II criteria (1-2 years), whereas 50.6% (n=42/83) recommended a screening or surveillance interval of 3 to 5 years and 17% (n=14/83) did not document a follow-up recommendation. Of the 17 providers who listed ‘Lynch Syndrome’ or ‘HNPCC’ as the indication for the procedure, 88% (n=15) recommended 1-2 year follow-up colonoscopy.

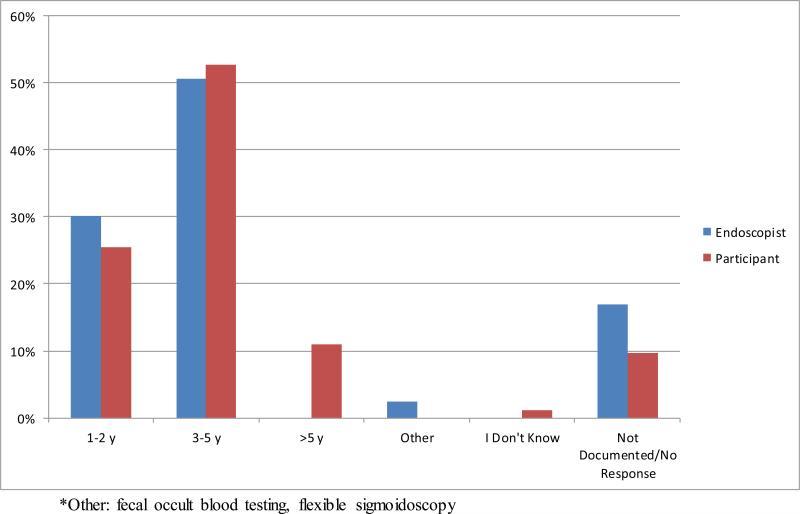

Concordance Between Endoscopists and Participants

Among the 83 participants with colonoscopy reports available, 69 had follow up recommendations documented either in the report, in the medical chart or on the pathology results sent to the participant. Three of these 69 were excluded from concordance analysis due to missing data from the participants’ reports of screening recommendations. A comparison of the participants’ understanding of appropriate screening intervals (as reported on the 24 month follow up survey) and the endoscopists’ screening recommendations made at the time of colonoscopy is shown in Figure 1a. There was a 65.2% (43/66) concordance (Figure 1b) between what the participant believed was the appropriate colorectal screening interval for themselves and what their endoscopist had recommended, corresponding to a weighted kappa statistic of 0.42 (95% CI 0.24-0.61) suggesting fair to moderate agreement. Only 27.3% (18/66) of the participant/endoscopist pairs were in agreement that 1-2 years was the appropriate screening interval.

Figure 1. Comparison of participant knowledge and endoscopist recommendation for colonoscopy screening interval.

a. Comparison of participant knowledge of colonoscopy screening interval at 24 months and endoscopist recommendation based on endoscopy reports.

b. Concordance between endoscopist recommendations and participant perceptions of colonoscopic screening recommendations.

When calculating concordance, the denominator excludes the participants who did not have an endoscopy report to review and participants who did not respond. Bold indicates concordance.

Impact of Genetic Testing Results on Colonoscopic Indications and Screening Recommendations

The participants who reported that they had had genetic testing represent special groups. The four participants with known negative genetic testing would no longer fall into the 1-2 year screening category. Despite this, two of these four participants (and their corresponding endoscopists) still recommended that their next screening should be in 1-2 years. The other 2 thought it should be in 2-5 years. Excluding these 4 participants from the analysis did not significantly alter the main results of the paper.

Of the eight participants who reported testing positive for a Lynch syndrome mutation, 5 thought that there next screening should be in 1-2 years but only 2 of their endoscopists reported HNPCC or Lynch syndrome as the indication for the colonoscopy; these two endoscopists recommended a 1-2 years surveillance interval, the other 6 recommended a 3-5 year interval.

Discussion

Lynch Syndrome is the most common hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, yet it is grossly under-recognized, resulting in missed opportunities to capture high-risk patients and their family members for appropriate genetic counseling and colonoscopic screening. The present study is one of the largest reports to date of the knowledge and uptake of genetic testing and guideline-based colonoscopic screening recommendations among CRC-unaffected individuals who meet Amsterdam II criteria.

We found that although the majority of participants acknowledged the importance of family history in CRC risk and had heard of genetic testing, less than 10 percent had undergone genetic testing. Further, only one third of participants reported that their providers had advised them to undergo genetic testing and a large proportion (27%) of participants who said that their family members had undergone genetic testing were unaware of the results. These findings demonstrate a major deficit in guideline-based care for members of HNPCC families in the US and highlight the need to improve education of both providers and family members about the importance of the cancer family history as a tool to identify individuals at risk for a hereditary CRC syndrome. These data also underscore the importance of communication about genetic test results within families in order to assure that at-risk members are provided adequate information about their familial risk of CRC.

Our results demonstrate very poor knowledge of and adherence to recommended colonoscopic screening intervals among both high risk patients and their providers. Although knowledge of appropriate screening interval improved slightly among participants from baseline to 24 months, there appears to have been very little impact from the intensive telephone intervention despite the fact that participants received direct counseling that they should undergo colonoscopy every 1-2 years based on their level of risk. This suggests that education alone (at least that provided outside of the usual clinical setting) may not be sufficient to change perceptions in persons at increased risk. Our data suggests that the provider recommendation is a very important factor in participant understanding of screening intervals. Only 30% of the endoscopists for this high-risk population recommended colonoscopic screening every 1-2 years, and the concordance between what the endoscopist recommended and what the participant reported as appropriate was moderate (65%). This would imply that patients are likely to adhere to what their provider recommends despite information provided through phone or mail-based interventions such as that used for FHPP and indicates that provider education is a critical element of any intervention to improve screening rates in this high risk group.

Our findings concur with those from a study by Stoffel et al22 that surveyed 181 patients from hereditary clinics in the US about their screening uptake. Twenty seven percent of these patients had inadequate screening (≥ 1-2 years) and of these, half had a colonoscopy within the last three to five years as per their doctors’ recommendations, whereas only 24% reported that their provider had recommended 1-2 years. These findings along with those reported in our study suggest that efforts to improve adherence to recommended guidelines in potential Lynch families should include both patient and provider-directed strategies.

Participants who were recruited because their family member was being seen in a high risk cancer clinic were about 20% more likely to report that they had heard of genetic testing and had discussed genetic testing with their provider but this did not translate into higher rates of referral for or completion of genetic testing. Interestingly, although there was no difference at baseline, participants recruited from high risk clinics exhibited significantly better knowledge of appropriate screening intervals at 24 months after enrollment regardless of whether they were in minimal or intensive intervention group. Participants from high risk clinics were also were more likely to be adherent to colonoscopic screening than those recruited from a population based registry; again with no difference based intervention group. This suggests that families who are seen at high risk clinics are at an advantage in terms of risk recognition and can benefit from the education and services provided by these clinics. Additionally, it suggests that at-risk families in the population at-large, which constitute the majority of Lynch families, at not getting the information that they need to reduce their CRC risk.

There are likely multiple reasons for the low level of knowledge about risk-appropriate colonoscopy screening guidelines among high risk persons but in this population it does not appear to be due to a lack of awareness of the importance of family history as a risk factor for CRC or due to a lack of interest or concern about cancer risk or a lack of awareness of the importance of CRC screening. We previously reported that approximately 90% of the participants in FHPP who met Amsterdam II criteria recognized that their family history of CRC increased their own risk, 80% were concerned about getting CRC and 95% thought that CRC screening was part of good overall health care.19 Possible contributing factors may include lack of awareness of different risk categories (Amsterdam II criteria versus other family history), limited family communication about risk, screening behavior of other family members and the overall media and physician emphasis on promoting recommendations for the average risk population with less attention focused on high risk groups. Although FHPP participants, particularly those recruited via population-based sources, generally recognized that they are at increased risk due to their family history, many may not have known that their family history was suggestive of a hereditary syndrome.

The reasons for the low level of appropriate screening recommendations (30%) by providers are also likely multi-factorial but failure to recognize that patients meet Amsterdam II criteria is likely a major contributor. Lynch syndrome is grossly under-recognized10 in part because providers often do not have access to a full family history.23 This is more likely to be an issue in open access endoscopy units where the patients are not seen by the endoscopist prior to the procedure. In our study, Lynch Syndrome or HNPCC was listed as the indication for the procedure in only 20 percent of the colonoscopy reports despite the fact that all of the patients had a family history that met Amsterdam II criteria. A much larger proportion of physicians listed “family history” as the indication for colonoscopy, suggesting that either the physicians were not aware of the full extent of the family history or that they did not recognize that the family history met Amsterdam II criteria. Our data demonstrate a very low level of recognition of a potential hereditary syndrome among endoscopist for patients at-risk for Lynch syndrome.

When providers recognized that their patients were from Lynch or HNPCC families they were much more likely to recommend appropriate screening intervals. This suggests that a major reason that providers fail to recommend guideline-based screening is that they may not be aware (or may not recognize) that the patient meets Amsterdam II criteria. Lack of knowledge of current colonoscopic screening recommendations for HNPCC and Lynch Syndrome is likely a smaller contributor as these guidelines are readily accessible and broadly endorsed by the gastroenterology community.5, 7, 8

This study has several strengths. It is one of the largest studies to assess knowledge of screening intervals among individuals meeting Amsterdam II criteria who are unaffected by colorectal cancer. The data was collected systematically and prospectively as part of a randomized controlled trial in contrast to most studies of HNPCC/Lynch Patients that rely on retrospective chart reviews.13-18, 24 The endoscopists’ recommendations were collected from the medical record (endoscopy reports) rather than by physician surveys which are less likely to capture true practice. An additional strength to our study is the inclusion of participants who met Amsterdam II criteria identified through population-based sources (43%). Thus, our results are more likely reflect the knowledge and practices of a greater population of persons at risk for Lynch Syndrome than reports derived exclusively from high risk clinics.

There are also several limitations to our analyses. The participants were a selected cohort of mostly insured, educated and affluent individuals who had already been enrolled in a registry that focused on cancer family history. CRC screening knowledge is likely to be higher in this population than in the general population suggesting that the problem of low level of knowledge of risk-appropriate guidelines might be even more pronounced in the general population than we found in this group. We were only able to evaluate endoscopist recommendations for participants who underwent colonoscopy during the study period. Thus, we were only able to obtain endoscopist surveillance recommendations from a subset (n=83) of the total group (n=165). However, we did not find any significant differences in baseline characteristics between those who had or did not have a colonoscopy. Genetic testing results were self-reported and not confirmed by medical records. There was a limited response in the supplemental questionnaire regarding how genetic testing discussions are initiated and barriers to obtaining genetic testing. Although there was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between those who filled out the supplemental questionnaire and those who did not, we cannot ensure that these groups were equivalent in their attitudes. Negative genetic testing is unlikely to have influenced participants/endoscopists knowledge of surveillance intervals as the overall results of knowledge were no different when the participants who reported testing negative were excluded.

In summary, this analysis demonstrates that individuals meeting Amsterdam II criteria are not often advised to have genetic testing and those who are have low uptake of genetic testing. In this experience, participants meeting Amsterdam II criteria have poor knowledge of appropriate screening guidelines and their endoscopists do not appear to recognize their increased risk and typically do not recommend appropriate screening intervals. Patients, even those who received an intervention recommending evidence-based screening intervals, tended to agree with their providers’ follow-up recommendations rather than those provided by our intervention. These results highlight the possible futility of interventions directed to individuals that are not part of their medical care as well as the importance of using multi-targeted approaches that include educational interventions for both providers and patients in order to improve recognition, screening and surveillance of individuals at risk for Lynch syndrome.

Study Highlights.

What is Current Knowledge

Lynch Syndrome is the most common hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome and has a 50-80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer

Lynch Syndrome is grossly under-recognized

Current guidelines recommend that individuals who meet Amsterdam II clinical criteria should be referred for genetic counseling and undergo colonoscopy every 1-2 years

What is New

In this experience, a minority of individuals who meet Amsterdam II criteria are referred for genetic testing or are aware that they should be undergoing colonoscopy every 1-2 years

A minority of endoscopists recommend appropriate 1-2 year surveillance intervals for this high risk group

There is moderate concordance between participant knowledge and physician recommendations

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by grant UM1 CA167551 from the National Cancer Institute and through cooperative agreements with the following CCFR centers: USC Consortium Colorectal Cancer Family Registry U01/U24 CA074799), Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (U01/U24 CA074800), Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01/U24 CA074794). Seattle CCFR research was also supported by the Cancer Surveillance System of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, which was funded by Control Nos. N01-CN-67009 (1996-2003) and N01-PC-35142 (2003-2010) and Contract No. HHSN2612013000121 (2010-2017) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute with additional support from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Similarly, the collection of cancer incidence data used in this study for LA country was also supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute, any of the collaborating centers in the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR), the State of California Department of Public Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HNPCC

Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer

- CRC

Colorectal Cancer

- FHPP

Family Health Promotion Project

- CGN

Cancer Genetics Network

- CFR

Cancer Family Registry

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: none.

References

- 1.Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Petersen GM. AGA technical review on hereditary colorectal cancer and genetic testing. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:198–213. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, et al. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1453–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:197–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colorectal Cancer Screening. 2013;2014 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0003. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colorectal_screening.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Genetic Testing and Management of Hereditary Gastrointestinal Cancer Syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223–62. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasen HF, Tomlinson I, Castells A. Clinical management of hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:88–97. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:829–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampel H, de la Chapelle A. The search for unaffected individuals with Lynch syndrome: do the ends justify the means? Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1–5. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claes E, Denayer L, Evers-Kiebooms G, et al. Predictive testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: subjective perception regarding colorectal and endometrial cancer, distress, and health-related behavior at one year post-test. Genet Test. 2005;9:54–65. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins V, Meiser B, Gaff C, et al. Screening and preventive behaviors one year after predictive genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:273–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadley DW, Jenkins JF, Dimond E, et al. Colon cancer screening practices after genetic counseling and testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:39–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halbert CH, Lynch H, Lynch J, et al. Colon cancer screening practices following genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) mutations. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1881–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson KA, Trimbath JD, Petersen GM, et al. Impact of genetic counseling and testing on colorectal cancer screening behavior. Genet Test. 2002;6:303–6. doi: 10.1089/10906570260471831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner A, van Kessel I, Kriege MG, et al. Long term follow-up of HNPCC gene mutation carriers: compliance with screening and satisfaction with counseling and screening procedures. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-0658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Dijk DA, Oostindier MJ, Kloosterman-Boele WM, et al. Family history is neglected in the work-up of patients with colorectal cancer: a quality assessment using cancer registry data. Fam Cancer. 2007;6:131–4. doi: 10.1007/s10689-006-9114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh H, Schiesser R, Anand G, et al. Underdiagnosis of Lynch syndrome involves more than family history criteria. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowery JT, Marcus A, Kinney A, et al. The Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP): design and baseline data from a randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in high risk families. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:426–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anton-Culver H, Ziogas A, Bowen D, et al. The Cancer Genetics Network: recruitment results and pilot studies. Community Genet. 2003;6:171–7. doi: 10.1159/000078165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowery JT, Horick N, Kinney AY, et al. A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:601–10. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoffel EM, Mercado RC, Kohlmann W, et al. Prevalence and predictors of appropriate colorectal cancer surveillance in Lynch syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1851–60. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SG, Ahnen DJ. Familial colon cancer syndromes: an update of a rapidly evolving field. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:428–38. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleiker EM, Menko FH, Taal BG, et al. Screening behavior of individuals at high risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:280–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]