Abstract

Background

Lactation improves glucose metabolism, but its role in preventing type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) after gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) remains uncertain.

Objective

To evaluate lactation and the 2-year incidence of DM after GDM pregnancy.

Design

Prospective, observational cohort of women with recent GDM. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01967030)

Setting

Integrated health care system.

Participants

1035 women diagnosed with GDM who delivered singletons at 35 weeks' gestation or later and enrolled in the Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy from 2008 to 2011.

Measurements

Three in-person research examinations from 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (baseline) and annual follow-up for 2 years that included 2-hour, 75-g oral glucose tolerance testing; anthropometry; and interviews. Multivariable Weibull regression models evaluated independent associations of lactation measures with incident DM adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

Of 1010 women without diabetes at baseline, 959 (95%) were evaluated up to 2 years later; 113 (11.8%) developed incident DM. There were graded inverse associations for lactation intensity at baseline with incident DM and adjusted hazard ratios of 0.64, 0.54, and 0.46 for mostly formula or mixed/inconsistent, mostly lactation, and exclusive lactation versus exclusive formula feeding, respectively (P trend = 0.016). Time-dependent lactation duration showed graded inverse associations with incident DM and adjusted hazard ratios of 0.55, 0.50, and 0.43 for greater than 2 to 5 months, greater than 5 to 10 months, and greater than 10 months, respectively, versus 0 to 2 months (P trend = 0.007). Weight change slightly attenuated hazard ratios.

Limitation

Randomized design is not feasible or desirable for clinical studies of lactation.

Conclusion

Higher lactation intensity and longer duration were independently associated with lower 2-year incidences of DM after GDM pregnancy. Lactation may prevent DM after GDM delivery.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a disorder of glucose tolerance affecting 5% to 9% of all U.S. pregnancies (approximately 250 000 annually) (1), with a 7-fold higher risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) (2). Strategies during the postpartum period for prevention of DM focus on modification of lifestyle behaviors, including dietary intake and physical activity, adapted from the Diabetes Prevention Program to promote weight loss (3, 4). Lactation is a modifiable postpartum behavior that improves glucose and lipid metabolism and increases insulin sensitivity (5–10) and has favorable metabolic effects that persist after weaning (11, 12).

Despite these benefits, evidence that lactation prevents type 2 DM remains inconclusive, particularly among women with GDM (5–10, 13). Two prospective epidemiologic studies, based on self-report of DM and initiation of follow-up many years after childbearing, reported weak to modest risk reductions of 3% to 15% per year of lactation among middle-aged and older U.S. nurses (14) or Chinese women (15). However, these findings are subject to reverse causation (such as lower perinatal body mass index or greater insulin sensitivity leading to longer lactation) and potential confounding by unmeasured risk factors (such as GDM history, degree of glucose intolerance, perinatal outcomes, and lifestyle behaviors) that may determine lactation initiation and duration.

Among women with GDM, evidence that lactation prevents DM is based on only 2 studies with conflicting findings. A large, retrospective study of U.S. nurses was null (14), whereas a prospective study reported a 46% lower incidence of DM at 15 years or more after delivery with lactation of 3 months or longer (16). Although this study screened for glucose tolerance at regular intervals, statistical power was inadequate for the 264 women to estimate excess DM incidence earlier than 15 years after delivery or graded associations with lactation (16). This study also lacked measures of perinatal risk factors, lifestyle behaviors, and weight change after delivery. Thus, the entire body of evidence cannot rule out reverse causation and potential confounding from unmeasured determinants of lactation behavior. Also, weight change by 1 year after delivery has not been previously evaluated as a mediator.

To overcome previous limitations and because random assignment of women to either breastfeeding or formula-feeding groups is not desirable or feasible in clinical studies, SWIFT (Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy) prospectively quantified lactation duration and intensity, assessed risk factors for reverse causation and potential confounders, and conducted standardized glucose tolerance testing 6 to 9 weeks after delivery and thereafter annually for 2 years. We hypothesized that higher intensity and longer duration of lactation prevent progression to DM within 2 years, independent of relevant risk factors and determinants of lactation success.

Methods

Study Population

The SWIFT study design and research method have been previously described (17). In brief, 1035 women diagnosed with GDM by Carpenter–Coustan criteria (18) were enrolled from August 2008 to December 2011. They received prenatal care and delivered at Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospitals and met other eligibility criteria based on telephone screenings during late gestation and after delivery to assess breastfeeding and formula use. The overall response rate was 55%, and 64% of the eligible respondents enrolled. Participants provided informed consent at the in-person examination at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (baseline) before collection of blood specimens from a 2-hour, 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT); completion of surveys; anthropometric and body composition measurements; and annual in-person follow-up examinations for 2 years (October 2008 to June 2014) (17). The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria (Supplement, available at www.annals.org) included diagnosis of GDM, live birth at 35 weeks' gestation or later, age 20 to 45 years, no history of diabetes, English- or Spanish-speaking, no serious medical conditions, and classification of infant feeding as intensive lactation or intensive formula feeding. Women recorded daily formula feeding (amount and frequency) from delivery through 6 weeks thereafter to estimate cumulative intake of formula and other supplements (17). Telephone interviews at 4 to 6 weeks after delivery identified women who fell into an intensive lactation (≤6 oz of formula per 24 hours since delivery) or intensive formula feeding (≥14 oz of formula per 24 hours for 3 weeks, no breast milk, or previous breastfeeding and weaned in ≤3 weeks) group. We excluded 83 women who reported mixed feeding (formula supplementation of 7 to 13 oz per 24 hours) or inconsistent feeding (transition to ≥14 oz of formula per 24 hours after 3 weeks of lactation) at the eligibility screening interview within 4 to 6 weeks after delivery (17).

Data Collection Procedures

Women who met study criteria were mailed instructions to follow an unrestricted diet for 3 days preceding the OGTT and to fast at least 10 hours the night before. At each in-person examination, fasting blood specimens were collected between 7:00 and 10:30 a.m. before consumption of 75 g of dextrose (Fisherbrand). Plasma aliquots obtained from fasting and 2-hour postload blood samples were stored at −70 °C until being transported to the University of Washington Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories (Seattle, Washington), which performed enzymatic assays for glucose and double-antibody radioimmunoassays for total insulin developed by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Immunoassay Core Laboratory (Seattle, Washington) (5).

Prospective Quantitative Assessment of Lactation Intensity and Duration

Trained research staff assessed lactation intensity and duration prospectively via feeding diaries, telephone calls, in-person examinations, and monthly mailed questionnaires to collect the exact date and age (months and days) of weaning (17). Lactation intensity at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (baseline) represents the cumulative amount of formula and breast milk fed since delivery and the intensity for the past 7 days (average number of breast milk– and formula-feeding episodes per 24 hours; quantity of formula per feeding; and total number of feedings per day, including water, other liquids, or solids). We classified women into 1 of the 4 following lactation intensity groups at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery: exclusive lactation (no formula, foods, or liquids), mostly lactation (>0 to 6 oz of formula per 24 hours), mostly formula (>17 oz per 24 hours) and mixed (7 to 17 oz of formula per 24 hours) or inconsistent lactation pattern, and exclusive formula feeding (formula only; no breastfeeding or breastfeeding <3 weeks) since birth. Women who transitioned into the mixed or inconsistent group after eligibility screening and before enrollment (n = 101) were classified as mostly formula feeding based on similar DM incidence.

Classification of Glucose Tolerance and Incident DM

Glucose tolerance at the baseline examination was evaluated by administration of the 2-hour, 75-g OGTT. Women with elevations that indicated a DM diagnosis at baseline confirmed on 2 separate occasions or those without repeated testing were excluded from longitudinal follow-up for incident DM.

Incident DM was identified via this test, which was administered during annual SWIFT follow-up examinations. In addition, electronic medical records from health plans were used to identify incident DM based on clinical laboratory tests (fasting, 2-hour OGTT, or random glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin); International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, diagnostic codes confirmed with laboratory results; and receipt of DM medications. For participants receiving outside follow-up care, we also used self-report of DM with health care provider diagnosis. Glucose tolerance categories included normal, glucose intolerant (impaired fasting glucose level of 5.55 to 6.94 mmol/L [100 to 125 mg/dL] or impaired glucose tolerance from the 2-hour, 75-g OGTT postglucose level of 7.77 to 11.04 mmol/L [140 to 199 mg/dL]), or DM (OGTT fasting glucose levels ≥6.99 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dL], 2-hour glucose levels ≥11.10 mmol/L [≥200 mg/dL], random glucose levels ≥11.10 mmol/L [≥200 mg/dL], or glycosylated hemoglobin levels ≥6.5%) via the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria (18). Elevations after baseline that indicated a DM diagnosis were confirmed by repeated laboratory tests outside of any subsequent pregnancies.

Anthropometry and Adiposity Measurements

Research staff used standardized protocol and research-quality calibrated instruments at each examination to measure weight, height, and waist circumference as previously described (17). Body weight was measured in light clothing and at standing height without shoes. Waist circumference was measured midway between the iliac crest and the lowest lateral portion of the rib cage and anteriorly midway between the xiphoid process of the sternum and the umbilicus. The 2 consecutive measurements were followed by a third if these measurements diverged by 1 cm or greater (17). Weight at baseline was subtracted from weight at 1 year after delivery to evaluate changes associated with lactation.

Perinatal Course and Outcomes

Electronic medical records provided prenatal 3-hour, 100-g OGTT results; GDM treatment type (diet, oral medications, or insulin), prepregnancy or first trimester body weight; delivery weight; and perinatal (GDM diagnosis date, delivery method, and discharge diagnoses) and newborn outcomes (birthweight, length, gestational age, neonatal intensive care unit admission, medical diagnoses, Apgar score, and length of hospital stay).

Lifestyle Behaviors and Depression

Interviewer- and self-administered, validated questionnaires assessed dietary intake, depression, and physical activity at each examination. PrimeScreen, a brief questionnaire about food frequency (reproducibility of 0.70 for foods and food groups and 0.74 for nutrients), assessed dietary intake of fat, fiber, and several other nutrients (19). A slightly modified version (17) of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire, a 32-item, semiquantitative, validated questionnaire (reproducibility measures of 0.78 to 0.93), was used to assess physical activity during the postpartum period (20). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (21) was used for longitudinal evaluation of depressive symptoms to achieve consistent measurements across the 3 examinations during the 2-year study.

Reproductive, Medical, and Sociodemographic Characteristics

Data collection occurred via in-person examination interviews, monthly mailed surveys, and telephone interviews, as well as via health plan electronic medical records to obtain current medical conditions (diagnosis and treatment), medication use (including hormonal contraceptives), subsequent pregnancies and perinatal outcomes, infant health history, family history of diabetes, education, parity, participation in low-income nutrition programs, age, and race/ethnicity.

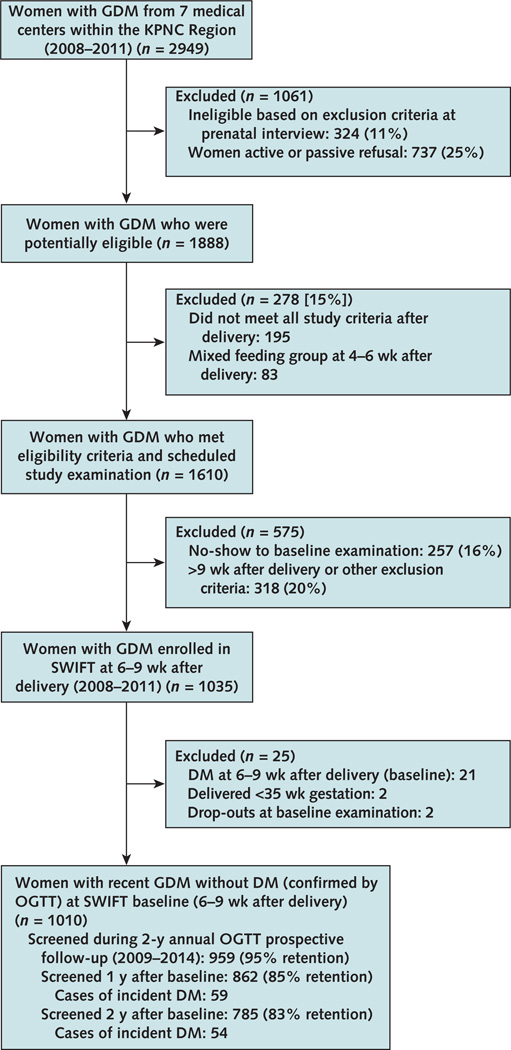

Analytic Sample and Retention

Of 1035 enrollees, 21 women with DM who had elevated glucose levels (fasting glucose level ≥6.99 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dL] or 2-hour glucose level ≥11.10 mmol/L [≥200 mg/dL]) from the 2-hour OGTT at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (baseline) were excluded. We also excluded 2 dropouts at baseline and 2 women who delivered at less than 35 weeks' gestation. After these exclusions, 1010 SWIFT participants without DM at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery were followed and rescreened annually for 2 years to ascertain DM incidence (Figure). We identified 59 DM cases within 1 year (screened 862 of 1010 [85%]) and 54 DM cases from 1 to 2 years (screened 785 of 951 at risk [83%]). Overall, 959 (95%) participants were evaluated for glucose tolerance at least once during the 2-year follow-up (defined as <32 months after baseline): 688 at both years 1 and 2, 174 at year 1 only, and 97 at year 2 only.

Figure. Study flow diagram.

DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; KPNC = Kaiser Permanente Northern California; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; SWIFT = Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy.

Statistical Methods

We compared characteristics of women and newborns by incident DM status during follow-up using t tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Prenatal, postpartum, and newborn characteristics were compared across lactation intensity groups using 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables, chi-square tests for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for medians. We used the Fisher exact test for cell sizes of less than 5. The Weibull regression model (a flexible, parametric survival model) was used for point and interval estimation of hazard ratios and 95% CIs of DM associated with lactation intensity and duration and controlled for confounding variables (22). Analyses accounted for standard right censoring due to not having DM at the last examination during follow-up and for interval censoring due to DM screening at annual study examinations or routine clinical examinations. With interval censoring, the exact failure time for a woman without DM at an examination and diagnosed at the next examination is unknown. In addition to interval censoring with unequal screening intervals, regression analyses accommodated time-varying lactation duration in which women were appropriately categorized at each point in time during follow-up according to current lactation duration status, moving into the next highest-duration category when, and if, the duration category boundary was reached. On the basis of a priori decisions (17), selected groups of baseline, perinatal, and newborn covariates were included in regression models in succession to control for potential confounding or reverse causation due to perinatal risk factors and lifestyle behaviors. Weight change was added to the final model (all covariates included) to assess its role in the mediation of the lactation–DM association. We used SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute), for all analyses and PARM_ICE macro, version 3.2 (Free Software Foundation) (22), for regression analyses. A more detailed description of the modeling approach is provided in the Supplement. Tests of trends across increasing lactation intensity and duration categories were calculated by treating the ordinal categories as continuous variables in the regression models (coded as 1 through 4 across the 4 categories). Statistical significance was defined as P values (all 2-sided) less than 0.05.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The funding source had no role in the scientific conduct of this study, including the design, method, data analysis, interpretation of the results, or dissemination of findings.

Results

Of 1010 eligible participants without DM at baseline, median follow-up was 1.8 years (range, 0.2 to 2.6 years). During the 2-year follow-up, 959 women were assessed, and 113 (11.8%) developed incident DM: 59 of 862 (6.8%) at 1 year and 54 of 782 (6.9%) at 2 years. The overall incidence rate of DM was 5.64 cases per 1000 person-months (95% CI, 4.60 to 6.68) and ranged from 3.95 cases per 1000 person-months (CI, 2.07 to 5.83) for exclusive lactation to 8.79 cases per 1000 person-months (CI, 5.47 to 12.11) for exclusive formula use at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (Table 1) in a graded manner (P trend = 0.004). Of 113 DM cases, 77 were classified by 2-hour OGTTs; 16 by fasting or random glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin levels based on the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria (18) (Methods section); 11 by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, diagnostic codes and treatment with DM medications; 1 by self-report based on the health care provider's diagnosis; 1 by a 2-hour postload glucose level of 11.04 mmol/L (199 mg/dL); and 7 by fasting glucose levels of 6.88 to 69.94 mmol/L (124 to 125 mg/dL).

Table 1.

Crude Incidence Rates (95% CIs) of Type 2 DM Within 2 y of Follow-up Among Women With GDM Pregnancy, by Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery*

| Lactation Intensity Group | Sample, n | Participants With Incident DM, n |

Person-Months | Incidence Rate (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive formula | 153 | 27 | 3071.2 | 8.79 (5.47–12.11) |

| Mostly formula and mixed or inconsistent lactation | 214 | 29 | 4480.5 | 6.47 (4.11–8.83) |

| Mostly lactation | 387 | 40 | 8191.2 | 4.88 (3.37–6.39) |

| Exclusive lactation | 205 | 17 | 4299.6 | 3.95 (2.07–5.83) |

| Total | 959 | 113 | 20 042.5 | 5.64 (4.60–6.68) |

DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus.

959 female participants in SWIFT (Study of Women, Infant Feeding, and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy). P value for trend = 0.004.

Incident DM cases per 1000 person-months.

At baseline, women who later developed DM were heavier, of Hispanic or Asian race/ethnicity, more likely to receive insulin or oral medications to treat GDM, and more likely to deliver by cesarean section (Table 2). They also had slightly higher dietary consumption of animal fat, and physical activity scores (Table 2), as well as adverse newborn outcomes (large for gestational age and heavier birthweight), (Appendix Table 1, available at www.annals.org). Lactation intensity at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery (Appendix Tables 2 and 3, available at www.annals.org) was inversely associated with prepregnancy body mass index and neonatal intensive care unit admission and hospital stay but not with GDM treatment, gestational weight gain, severity of prenatal glucose intolerance (that is, the sum of 3-hour OGTT Z score), or history of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Lactation intensity at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery was directly associated with lactation duration (Appendix Table 4, available at www.annals.org)—the exclusive and mostly lactation groups breastfed for longer periods (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Prenatal and Baseline Characteristics of Women With GDM, by Incident DM Status During 2-y Follow-up*

| Characteristic | Incident DM (n = 113) | No DM (n = 846) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Mean age at baseline (SD), y | 33.9 (5.4) | 33.3 (4.7) | 0.197 |

| Mean educational level, n (%) | 0.002 | ||

| High school or less | 41 (36.3) | 189 (22.3) | |

| Some college | 33 (29.2) | 237 (28.0) | |

| College graduate | 39 (34.5) | 420 (49.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)† | 0.004 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 17 (15.0) | 208 (24.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13 (11.5) | 59 (7.0) | |

| Hispanic | 46 (40.7) | 246 (29.0) | |

| Asian | 36 (31.9) | 316 (37.4) | |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | 17 (2.0) | |

| Parity, n (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Primiparous | 38 (33.6) | 308 (36.4) | |

| Multiparous | 75 (66.4) | 538 (63.6) | |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome, n (%) | 18 (15.9) | 44 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| WIC recipient, n (%)‡ | 42 (37.2) | 204 (24.1) | 0.003 |

| Family history of DM, n (%) | 69 (61.1) | 404 (47.8) | 0.008 |

| Prenatal | |||

| Mean prepregnancy BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 33.4 (8.3) | 29.0 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy weight status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| BMI <25 kg/m2 | 15 (13.3) | 276 (32.6) | |

| BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 30 (26.6) | 257 (30.4) | |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 68 (60.1) | 313 (37.0) | |

| Mean gestational weight gain (SD), kg | 8.1 (8.4) | 10.6 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Mean 3-h, 100-g OGTT results (SD) | |||

| Fasting glucose level | <0.001 | ||

| mmol/L | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.0 (0.6) | |

| mg/dL | 100.3 (13.5) | 90.9 (11.5) | |

| 1-h glucose level | <0.001 | ||

| mmol/L | 11.8 (1.5) | 11.0 (1.2) | |

| mg/dL | 212.1 (26.5) | 197.7 (21.9) | |

| 2-h glucose level | <0.001 | ||

| mmol/L | 10.3 (1.8) | 9.7 (1.5) | |

| mg/dL | 186.4 (32.5) | 175.1 (26.5) | |

| 3-h glucose level | 0.004 | ||

| mmol/L | 7.5 (2.1) | 7.0 (1.8) | |

| mg/dL | 135.1 (38.2) | 125.5 (32.3) | |

| Mean sum of 3-h, 100-g OGTT Z scores (SD)§ | 1.9 (3.1) | −0.2 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean gestational age at GDM diagnosis (SD), wk | 22.3 (8.5) | 25.8 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Treatment of GDM, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Diet only | 46 (40.7) | 609 (72.0) | |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 52 (46.0) | 218 (25.7) | |

| Insulin | 15 (13.3) | 19 (2.3) | |

| Hospital labor and delivery | |||

| Mean length of gestation (SD), wk | 39.1 (1.2) | 39.1 (1.1) | 0.80 |

| Mean length of stay (SD), d | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 47 (41.6) | 258 (30.5) | 0.017 |

| 6 to 9 wk after delivery (baseline) | |||

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 33.4 (7.4) | 29.6 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean waist circumference (SD), cm | 97.0 (14.1) | 89.0 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Mean postdelivery weight change (SD), kg | −8.2 (4.0) | −9.2 (3.6) | 0.006 |

| Mean HOMA-IR index score (SD) | 8.5 (5.7) | 5.1 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Median HOMA-IR index score (IQR) | 7.4 (4.5–10.5) | 4.1 (2.8–6.3) | <0.001 |

| Mean 2-h, 75-g OGTT results (SD) | |||

| Fasting glucose level | <0.001 | ||

| mmol/L | 5.7 (0.6) | 5.2 (0.4) | |

| mg/dL | 102.4 (10.9) | 93.6 (8.1) | |

| 2-h postload glucose level | <0.001 | ||

| mmol/L | 7.4 (1.7) | 6.1 (1.5) | |

| mg/dL | 133.4 (30.4) | 109.5 (26.5) | |

| Glucose tolerance, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Normal | 33 (29.2) | 595 (70.3) | |

| IFG level only | 34 (30.1) | 142 (16.8) | |

| IGT only | 18 (15.9) | 77 (9.1) | |

| IFG level and IGT | 28 (24.8) | 32 (3.8) | |

| Depression, n (%) | 0.68 | ||

| None | 91 (85.1) | 710 (86.5) | |

| Moderate or severe | 16 (14.9) | 111 (13.5) | |

| Median lifestyle behaviors (IQR) | |||

| Total PA, metabolic equivalent h/wk | 46.5 (36.0–71.7) | 42.6 (31.5–55.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate to vigorous PA, metabolic equivalent h/wk | 24.4 (16.6–40.7) | 21.4 (14.0–30.6) | 0.005 |

| Dietary glycemic index | 220.5 (150.6–280.3) | 228.1 (172.0–302.1) | 0.24 |

| Dietary fiber, g/100 kcal | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.82 |

| Dietary animal fat, percentage of kcal | 26.8 (22.2–31.7) | 24.9 (19.7–30.8) | 0.023 |

| Contraception, n (%)† | 0.95 | ||

| Progesterone only | 3 (2.7) | 23 (2.7) | |

| Combination oral pills | 14 (12.4) | 104 (12.3) | |

| Intrauterine device | 12 (10.6) | 79 (9.3) | |

| None or barrier | 84 (74.3) | 640 (75.7) | |

| Subsequent birth (1 birth during 2-y follow-up), n (%) | 8 (7.1) | 106 (12.5) | 0.093 |

BMI = body mass index; DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HOMA-IR = Homeostatic Metabolic Assessment of Insulin Resistance; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; IQR = interquartile range; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; PA = physical activity; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Data were missing for depression score (n = 31), HOMA-IR index score (n = 5), and lifestyle behaviors (n = 5).

Fisher exact text for cell sizes <5.

Eligibility based on income ≤185% of the federal poverty level.

Sum of the 4 Z scores for the prenatal 100-g OGTT glucose values (fasting and 1, 2, and 3 h).

In multivariable regression models (Table 3), higher lactation intensity was associated with lower adjusted rates of incident DM in a monotonic gradient adjusted for age and covariates, including maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and life-style behaviors (all P trend < 0.025). Longer lactation duration (>2 to 5 months, >5 to 10 months, and >10 months compared with 0 to 2 months) was also independently associated with lower rates of incident DM (Table 4) in a monotonic gradient (all P trend < 0.01). Addition of newborn outcomes and lifestyle covariates to models adjusted for age and maternal and perinatal risk factors had minimal effect on observed associations. In a sensitivity analysis, exclusion of 7 DM cases classified by a fasting glucose level of 6.88 to 69.94 mmol/L (124 to 125 mg/dL) did not change our findings. Addition of weight change from delivery to 1 year thereafter, a potential mediator, modestly attenuated the associations between lactation intensity and duration with incident DM in models adjusted for age, maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and lifestyle behaviors (Tables 3 and 4). However, protective associations remained statistically significant (P trend < 0.05). The results of additional exploratory analyses are presented in the Supplement.

Table 3.

Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery and Adjusted HRs of Incident DM (95% CIs) Within 2-y Follow-up Among Women With GDM Pregnancy*

| Weibull Regression Proportional Hazards Model |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) of Incident DM Within 2 y of Follow-up, by Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery |

P Value for Trend |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive Formula (n = 153) |

Mostly Formula† and Mixed or Inconsistent Lactation (n = 214) |

Mostly Lactation‡ (n = 387) |

Exclusive Lactation (n = 205) |

||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.72 (0.43–1.23) | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | 0.43 (0.23–0.82) | 0.003 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors§‖ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.64 (0.37–1.12) | 0.54 (0.32–0.92) | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 0.016 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors and newborn outcomes§¶ |

1.00 (Reference) | 0.65 (0.37–1.13) | 0.53 (0.31–0.91) | 0.47 (0.25–0.91) | 0.017 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and postpartum lifestyle behaviors§** |

1.00 (Reference) | 0.66 (0.38–1.14) | 0.56 (0.32–0.95) | 0.48 (0.25–0.92) | 0.023 |

| Add potential mediator: weight change from delivery to 1 y†† | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.72 (0.41–1.28) | 0.67 (0.38–1.16) | 0.47 (0.24–0.93) | 0.048 |

DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HR = hazard ratio.

959 participants in SWIFT (Study of Women, Infant Feeding, and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy) and 113 incident cases of DM within 32 mo after baseline. Covariate data are complete except for those for lifestyle behaviors, which were missing for 5 women, and 1-y weight change, which were missing for 35 women.

>17 oz/24 h.

0–6 oz/24 h.

Addition of this selected group of covariates in succession to the age-adjusted model.

Race/ethnicity; education; prepregnancy body mass index; GDM treatment; sum of prenatal 3-h, 100-g oral glucose tolerance test Z score; gestational age at GDM diagnosis; and subsequent birth (1 vs. 0) during 2-y follow-up.

Large for gestational age vs. not large for gestational age (reference), hospital stay >3 d, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Total physical activity (metabolic equivalent h/wk), glycemic index, and percentage of kcal from animal fat (greater than the median percentage).

Added to full model adjusted for age, maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and postpartum lifestyle behaviors.

Table 4.

Lactation Duration Categories and Adjusted HRs of Incident DM (95% CIs) Within 2-y Follow-up Among Women With GDM Pregnancy*

| Weibull Regression Proportional Hazards Model |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) of Incident DM Within 2 y of Follow-up, by Time-Dependent Lactation Duration |

P Value for Trend |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 mo (n = 189) |

>2–5 mo (n = 190) |

>5–10 mo (n = 208) |

>10 mo (n = 372) |

||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.64 (0.36–1.13) | 0.44 (0.22–0.88) | 0.38 (0.20–0.71) | 0.001 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors†‡ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.55 (0.30–1.01) | 0.51 (0.25–1.01) | 0.44 (0.23–0.84) | 0.009 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors and newborn outcomes†§ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.55 (0.31–1.01) | 0.50 (0.25–0.99) | 0.43 (0.23–0.82) | 0.007 |

| Maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and postpartum lifestyle behaviors†‖ |

1.00 (Reference) | 0.54 (0.30–0.99) | 0.55 (0.28–1.09) | 0.43 (0.22–0.82) | 0.010 |

| Add potential mediator: weight change from delivery to 1 y¶ | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.48 (0.25–0.90) | 0.65 (0.33–1.24) | 0.47 (0.24–0.91) | 0.037 |

DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HR = hazard ratio.

959 participants in SWIFT (Study of Women, Infant Feeding, and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy) and 113 incident cases of DM within 32 mo after baseline. Covariate data are complete except for those for lifestyle behaviors, which were missing for 5 women, and 1-y weight change, which were missing for 35 women.

Addition of this selected group of covariates in succession to the age-adjusted model.

Race/ethnicity; education; prepregnancy body mass index; GDM treatment; sum of prenatal 3-h, 100-g oral glucose tolerance test Z score; gestational age at GDM diagnosis; and subsequent birth (1 vs. 0) during 2-y follow-up.

Large for gestational age vs. not large for gestational age (reference), hospital stay >3 d, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Total physical activity (metabolic equivalent h/wk), glycemic index, and percentage of kilocalories from animal fat (greater than the median percentage).

Added to full model adjusted for age, maternal and perinatal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and postpartum lifestyle behaviors.

Discussion

Our prospective assessment of both intensity and duration of lactation and annual evaluation of type 2 DM after GDM pregnancy provides robust evidence for the role of lactation in preventing DM among high-risk young women. We saw 36% to 57% relative reductions in the 2-year DM incidence with higher intensity of lactation at 6 to 9 weeks after delivery as well as for longer periods (>2 months through >10 months), independent of obesity, gestational glucose tolerance, and perinatal outcomes that can delay lactogenesis and thereby shorten lactation duration (23). Lifestyle may also affect lactation behavior but did not confound our findings, possibly due to high breastfeeding rates among racial and ethnic subgroups, particularly Hispanic and Asian women, in whom lifestyle behaviors may not influence infant feeding choices (that is, higher breastfeeding intensity and duration may not correlate with higher physical activity levels). Our findings also show that postpartum weight change only slightly mediated the lactation–DM association, a finding that had not been evaluated in previous studies.

To our knowledge, to date SWIFT was the largest and most ethnically diverse prospective cohort of women with GDM to conduct glucose tolerance testing annually from the early postpartum period, and it is the only study that prospectively quantified lactation intensity and duration and controlled for several perinatal and newborn potential confounders. Two previous studies of lactation and DM incidence in women with a history of GDM reported conflicting findings and did not account for perinatal outcomes, subsequent pregnancies, or postpartum lifestyle behaviors (14, 16). These same limitations characterize all other studies that enrolled women with unknown GDM history and initiated follow-up for most women many years after childbearing had ended (14, 15, 24–26). Thus, findings may result from reverse causation and potential confounding due to unmeasured risk factors for suboptimal lactation. The only previous prospective study of women with GDM (n = 264) had additional limitations, including inadequate power to assess graded associations and excess risks due to formula feeding only, or to evaluate excess DM rates within 2 to 5 years after delivery.

Modest weight loss is highly effective for preventing type 2 DM. In the Diabetes Prevention Program, participants in the lifestyle intervention group had an average 3- to 4-kg weight loss over 2 to 3 years that was associated with a 58% reduction in DM incidence (3, 27). Lactation increases energy expenditure (28) and mobilizes adipose stores in the femoral region and possibly visceral fat (29, 30). However, it has only slight effects on body composition and may have a minimal or no effect on postpartum weight loss, although evidence is mixed (9, 31–34). In our study, greater weight loss (1.0 to 1.3 kg) at 1 year after delivery for the exclusive or mostly lactation groups versus formula groups slightly mediated the association between lactation and lower DM incidence, although findings remained statistically significant. Previous studies examining the association have not evaluated postpartum weight change. Our findings indicate that the strong protective associations between lactation measures and progression to type 2 DM may involve mechanisms other than weight loss.

Potential mechanisms to explain the lower incidence of DM with higher intensity and duration of lactation include preservation of pancreatic β cells (35), less inflammation, and improved endothelial function; however, biochemical evidence is sparse. The hormone prolactin is known to increase pancreatic β-cell mass and function during human pregnancy, but effects on β cells during the peripartum and postpartum periods have not been delineated. In mice, a higher rate of maternal β-cell proliferation was reported in lactating groups than in nonlactating groups (36). In postpartum women with recent GDM, lactation enhances β-cell compensation for insulin resistance, resulting in better insulin sensitivity, glucose effectiveness, and first-phase insulin response to glucose according to the Bergman Minimal Model (9). In SWIFT, we previously reported an inverse association for lactation intensity and fasting blood lipids, glucose, and insulin resistance as well as the prevalence of prediabetes at study baseline independent of body mass index, race, or other risk factors (5, 6).

Prolactin also regulates adipogenesis to suppress lipid storage as well as release of the inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6 (37), and adiponectin from adipocytes (38). In SWIFT, lower fasting plasma adiponectin and leptin levels were associated with higher lactation intensity at baseline. As a risk factor for type 2 DM, this finding is consistent with prolactin's and possibly leptin's suppression of adiponectin release (37, 39) but conflicts with lower circulating adiponectin levels as a risk factor for type 2 DM (40). In other crosssectional studies that measured biomarkers once at 3 years after delivery, there was no association between lactation duration and nonfasting levels of blood glucose, lipids, adiponectin, leptin, or inflammatory markers (41, 42). Longitudinal changes in biomarkers from early postpartum to postweaning periods have not been directly linked with lactation and subsequent type 2 DM. These measurements are required to determine the biological plausibility for lactation's protection against type 2 DM after GDM delivery.

Limitations of the SWIFT study include the lack of longitudinal biomarker measures as mediators of lactation and progression to DM and the inability to evaluate the associations beyond 2 years of follow-up. However, SWIFT has several strengths, including recruitment of the largest and most racially or ethnically diverse cohort of women with standardized criteria for GDM diagnosis and treatment within a large integrated health care system; detailed prospective and quantitative assessment of lactation intensity and duration; annual screening for incident DM from the early postpartum period and annually thereafter for 2 years via the 2-hour, 75-g OGTT; research-quality measurements of body anthropometry; and high retention rates (17). Other strengths include evaluation of GDM severity, maternal risk factors, newborn outcomes, and postpartum lifestyle behaviors that can lead to delayed lactogenesis or shorter duration of lactation (23). By design, SWIFT minimized the reverse causation and residual confounding that lessen the validity of all previous studies. The SWIFT cohort was very diverse: 75% were Hispanic, Asian, or black, and 25% had household incomes that fell at or below 185% of the U.S. federal poverty guidelines. This contrasts with almost all previous studies, which predominantly included women of European ancestry, except a study of older Chinese women, and heightens the relevance of our findings for Hispanic, Asian, and black women at highest risk for GDM.

Women with a history of GDM are faced with an extremely high risk for type 2 DM; up to 50% diagnosed within 5 years after delivery (2, 43). In our study, both higher lactation intensity and duration showed strong, graded protective associations with DM incidence independent of risk factors (sociodemographic characteristics, prenatal metabolic status and course, perinatal outcomes, and lifestyle behaviors) that were not explained by weight loss. Thus, early DM strategies for postpartum women may need to refocus efforts to support optimal lactation intensity and duration, with later implementation of dietary and physical activity modifications after the period of intensive lactation. The coordinated and sequential timing of postpartum interventions among GDM women may involve several biological pathways and thereby maximize DM risk reduction.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for approximately 6 months, followed by continued breastfeeding with complementary foods for 1 year or longer (44). International professional bodies have recommended breastfeeding for women with GDM but have acknowledged that evidence was insufficient to conclude that it conferred longer-term metabolic benefits for women (45). Currently, only 43% of U.S. women report exclusively breastfeeding at 3 months, and by 6 months, only 51% are breastfeeding at all (46). Breastfeeding promotion may be a practical, low-cost intervention during the postpartum period to prevent diabetes in high-risk women, with the potential for benefits that are complementary to lifestyle interventions targeting weight loss. Modification of lactation behaviors to increase intensity and duration should be considered a high priority for pregnant and postpartum women with GDM because of their lasting metabolic benefits. Greater allocation of health care resources to promote and support exclusive and extended breastfeeding may benefit high-risk women by reducing their risk for midlife progression to DM.

Supplementary Material

EDITORS' NOTES.

Context

Lactation is a modifiable postpartum behavior that improves glucose and lipid metabolism. Whether lactation prevents type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) among women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is unclear.

Contribution

Investigators classified baseline infant feeding behaviors, including lactation intensity at baseline and lactation duration during follow-up for 1035 postpartum women with GDM. The women had oral glucose tolerance tests at baseline and annually for 2 years. The primary study outcome was the development of incident DM during follow-up.

Caution

Women were followed for only 2 years.

Implication

Higher intensity and longer duration of lactation were independently associated with decreased incidence of DM among women with GDM.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: By the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD050625 to Dr. Gunderson); the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR024131); the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefit Program; and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Dr. Gunderson reports grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Program, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources, and American Diabetes Association during the conduct of the study. Dr. Lo reports grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Sanofi outside the submitted work. Dr. Fox reports grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Program, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources, and the American Diabetes Association during the conduct of the study. Dr. Quesenberry reports grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development during the conduct of the study and grants from Takeda, Merck, Sanofi–Aventis, Lilly, Genentech, Valeant, and Pfizer outside the submitted work.

Appendix: SWIFT Investigators

SWIFT investigators who authored this work are Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MPH, MS, RD; Shanta R. Hurston, MPA; Xian Ning, MS; Joan C. Lo, MD; Yvonne Crites, MD; David Walton, MD; Kathryn G. Dewey, PhD; Robert A. Azevedo, MD; Stephen Young, MD; Gary Fox, MD; Cathie C. Elmasian, MD; Nora Salvador, MD; Michael Lum, MD; Barbara Sternfeld, PhD; and Charles P. Quesenberry Jr., PhD.

SWIFT investigators who contributed to this work but did not author it: Joseph Selby, MD, MPH; Assiamira Ferrara, MD, PhD; and Vicky Chiang, MS.

Appendix Table 1.

Characteristics of Infants Born to Women With GDM, by Incident DM Status Within 2-y Follow-up After GDM Pregnancy*

| Characteristic | Incident DM (n = 113) | No DM (n = 846) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean birthweight (SD), g | 3546 (576.9) | 3390 (484.8) | 0.002 |

| Mean length (SD), cm | 51.0 (2.5) | 50.5 (2.4) | 0.026 |

| Mean weight for length Z score (SD) | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.4) | 0.52 |

| Median weight for length Z score (IQR) | −0.3 (−1.1 to 0.7) | −0.3 (−1.2 to 0.5) | 0.47 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.145 | ||

| Female | 46 (40.7) | 406 (48.0) | |

| Male | 67 (59.3) | 440 (52.0) | |

| Gestational age, n (%) | 0.38 | ||

| 35 to <37 wk (preterm) | 7 (6.2) | 37 (4.4) | |

| ≥37 wk (term) | 106 (93.8) | 809 (95.6) | |

| Birthweight, n (%)† | 0.21 | ||

| 1500–2499 g | 3 (2.7) | 23 (2.7) | |

| 2500–2999 g | 17 (15.0) | 159 (18.8) | |

| 3000–3999 g | 74 (65.5) | 577 (68.2) | |

| ≥4000 g | 19 (16.8) | 87 (10.3) | |

| Size for gestational age, n (%)† | 0.013 | ||

| Small | 1 (0.9) | 18 (2.1) | |

| Appropriate | 75 (66.4) | 655 (77.4) | |

| Large | 37 (32.7) | 173 (20.5) | |

| Apgar score at 5 min, n (%)† | 0.26 | ||

| 6 or lower | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.1) | |

| 7 or higher | 110 (97.3) | 826 (97.6) | |

| Missing | 3 (2.7) | 11 (1.3) | |

| Newborn nursery, n (%) | 0.47 | ||

| NICU | 6 (5.3) | 39 (4.6) | |

| Brief/intermediate level | 10 (8.9) | 51 (6.0) | |

| Well care | 97 (85.8) | 756 (89.4) | |

| Hospital stay, n (%) | 0.149 | ||

| ≥3 d | 28 (24.8) | 161 (19.0) | |

| <3 d | 85 (75.2) | 685 (81.0) | |

DM = diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; IQR = interquartile range; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Chi-square test for categorical variables; t test or analysis of variance for continuous variables. Kruskal–Wallis test to compare medians.

Fisher exact test for cell sizes <5. Two-sided P values.

Appendix Table 2.

Prenatal and Baseline Characteristics of Women With GDM, by Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery (Study Baseline)*

| Characteristic | Exclusive Formula (n = 153) |

Mostly Formula, Mixed/Inconsistent (n = 214) |

Mostly Lactation (n = 387) |

Exclusive Lactation (n = 205) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Mean age at baseline (SD), y | 33.0 (4.9) | 33.4 (5.0) | 33.4 (4.8) | 33.5 (4.4) |

| Education, n (%)† | ||||

| High school or less | 60 (39.2) | 56 (26.2) | 79 (20.4) | 35 (17.1) |

| Some college | 55 (36.0) | 55 (25.7) | 106 (27.4) | 54 (26.3) |

| College graduate | 38 (24.8) | 103 (48.1) | 202 (52.2) | 116 (56.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)†‡ | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 34 (22.2) | 43 (20.1) | 79 (20.4) | 69 (33.6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 22 (14.4) | 19 (8.9) | 20 (5.2) | 11 (5.4) |

| Hispanic | 48 (31.4) | 68 (31.8) | 118 (30.5) | 58 (28.3) |

| Asian | 43 (28.1) | 80 (37.3) | 166 (42.9) | 63 (30.7) |

| Other | 6 (3.9) | 4 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) |

| Parity, n (%) | ||||

| Primiparous | 49 (32.0) | 93 (43.5) | 132 (34.1) | 72 (35.1) |

| Multiparous | 104 (68.0) | 121 (56.5) | 255 (65.9) | 133 (64.9) |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome, n (%) | 10 (6.5) | 11 (5.1) | 31 (8.0) | 10 (4.9) |

| WIC recipient, n (%)† | 59 (38.6) | 55 (25.7) | 87 (22.5) | 45 (22.0) |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | 70 (45.8) | 103 (48.1) | 204 (52.7) | 96 (46.8) |

| Prenatal | ||||

| Mean prepregnancy BMI (SD), kg/m2† | 31.2 (8.3) | 30.0 (7.8) | 29.3 (6.7) | 28.3 (6.1) |

| Prepregnancy weight status, n (%)§ | ||||

| BMI <25 kg/m2 | 38 (24.8) | 66 (30.8) | 114 (29.5) | 73 (35.6) |

| BMI 25 of <30 kg/m2 | 37 (24.2) | 60 (28.0) | 125 (32.3) | 65 (31.7) |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 78 (51.0) | 88 (41.2) | 148 (38.2) | 67 (32.7) |

| Mean gestational weight gain (SD), kg | 10.8 (7.9) | 10.2 (6.5) | 10.2 (6.5) | 10.3 (6.9) |

| Mean 3-h, 100-g OGTT (SD), mg/dL | ||||

| Fasting glucose level | 92.2 (11.4) | 93.4 (11.1) | 92.0 (12.6) | 90.4 (12.8) |

| 1-h glucose level | 199.0 (22.1) | 201.3 (23.0) | 198.6 (23.2) | 199.1 (23.1) |

| 2-h glucose level | 177.1 (25.0) | 176.3 (28.8) | 176.0 (29.2) | 176.7 (24.7) |

| 3-h glucose level | 126.3 (34.7) | 128.5 (31.1) | 127.8 (33.3) | 122.7 (33.7) |

| Mean sum of 3-h OGTT Z scores (SD) | 0.0 (2.3) | 0.3 (2.6) | 0.0 (2.8) | −0.2 (2.6) |

| Median sum of 3-h OGTT Z scores (IQR) | −0.3 (−1.6 to 1.3) | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.4) | −0.6 (−1.8 to 1.3) | −0.7 (−1.9 to 0.7) |

| Mean gestational age at GDM diagnosis (SD), wk | 24.9 (7.8) | 24.9 (7.2) | 25.4 (6.9) | 26.4 (6.5) |

| Treatment of GDM, n (%)‡ | ||||

| Diet modification only | 108 (70.6) | 141 (65.9) | 263 (68.0) | 143 (69.8) |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 43 (28.1) | 65 (30.4) | 105 (27.1) | 57 (27.8) |

| Insulin | 2 (1.3) | 8 (3.7) | 19 (4.9) | 5 (2.4) |

| Hospital labor and delivery | ||||

| Mean length of gestation (SD), wk‖ | 39.0 (1.1) | 39.3 (1.1) | 38.9 (1.2) | 39.2 (1.0) |

| Mean length of stay (SD), d† | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) |

| Cesarean section, n (%)§ | 61 (39.9) | 74 (34.6) | 113 (29.2) | 57 (27.8) |

| 6 to 9 wk after delivery (baseline) | ||||

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2† | 32.0 (7.7) | 30.6 (7.1) | 29.8 (6.4) | 28.5 (5.2) |

| Mean waist circumference (SD), cm† | 93.6 (14.9) | 91.5 (15.8) | 89.1 (13.1) | 86.9 (11.0) |

| Mean weight change postdelivery (SD), kg | −8.9 (4.0) | −8.7 (3.7) | −9.1 (3.6) | −9.5 (3.4) |

| Mean HOMA-IR index score (SD)† | 7.0 (4.1) | 6.5 (5.1) | 4.9 (3.2) | 4.3 (2.8) |

| Median HOMA-IR index score (IQR)† | 5.9 (4.0–8.7) | 5.1 (3.1–8.5) | 4.1 (2.7–6.3) | 3.5 (2.6–5.1) |

| Mean 2-h, 75-g OGTT results (SD) | ||||

| Fasting glucose level, mg/dL† | 97.8 (9.1) | 97.3 (10.2) | 93.2 (8.0) | 92.2 (7.9) |

| 2-h postload glucose level, mg/dL† | 110.6 (25.8) | 117.4 (27.6) | 113.0 (28.5) | 106.9 (28.4) |

| Mean 2-h, 75-g OGTT results (SD) | ||||

| Fasting glucose level, mmol/L† | 5.4 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.6) | 5.1 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.4) |

| 2-h postload glucose level, mmol/L† | 6.1 (1.4) | 6.5 (1.5) | 6.2 (1.6) | 5.9 (1.6) |

| Glucose tolerance, n (%)† | ||||

| Normal | 89 (58.2) | 119 (55.6) | 265 (68.5) | 155 (75.6) |

| IFG level only | 43 (28.1) | 53 (24.8) | 53 (13.7) | 27 (13.2) |

| IGT only | 9 (5.9) | 20 (9.3) | 50 (12.9) | 16 (7.8) |

| IFG level and IGT | 12 (7.8) | 22 (10.3) | 19 (4.9) | 7 (3.4) |

| Depression, n (%) | ||||

| None | 126 (86.3) | 174 (84.5) | 325 (86.0) | 176 (88.9) |

| Moderate or severe | 20 (13.7) | 32 (15.5) | 53 (14.0) | 22 (11.1) |

| Median lifestyle behaviors (IQR) | ||||

| Total PA, metabolic equivalent h/wk§ | 46.5 (35.4–61.1) | 41.8 (32.2–59.4) | 42.8 (30.4–54.6) | 42.9 (31.3–54.1) |

| Moderate to vigorous PA, metabolic equivalent h/wk | 24.3 (16.2–35.6) | 22.0 (14.3–33.5) | 21.5 (13.7–30.3) | 20.5 (13.5–29.7) |

| Glycemic index† | 186.5 (136.4–375.2) | 223.6 (166.5–280.3) | 232.5 (177.7–313.1) | 248.9 (186.4–337.5) |

| Dietary fiber, g/100 kcal† | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) |

| Dietary animal fat, percentage of kcal† | 28.4 (18.8–33.5) | 25.8 (19.4–31.3) | 24.4 (18.9–30.3) | 24.2 (19.5–29.4) |

| Contraception methods, n (%)‡ | ||||

| Progesterone only | 8 (5.2) | 4 (1.9) | 10 (2.6) | 4 (2.0) |

| Combination oral pills | 24 (15.7) | 20 (9.4) | 46 (11.9) | 28 (13.7) |

| Intrauterine device | 17 (11.1) | 18 (8.3) | 41 (10.6) | 15 (7.3) |

| None/barrier | 104 (68.0) | 172 (80.4) | 290 (74.9) | 158 (77.0) |

| Subsequent birth (1 birth during 2-y follow-up), n (%) | 16 (10.5) | 32 (15.0) | 44 (11.4) | 22 (10.7) |

BMI = body mass index; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HOMA-IR = Homeostatic Metabolic Assessment of Insulin Resistance; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; IQR = interquartile range; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; PA = physical activity; sum of 3-h OGTT Z scores = sum of the 4 Z scores for the prenatal 100-g OGTT glucose values (fasting and 1, 2, and 3 h); WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (eligibility based on income ≤185% of the federal poverty level).

Chi-square test for categorical variables; t test or analysis of variance for continuous variables. Kruskal–Wallis test to compare medians. Data were missing for depression score (n = 31), HOMA-IR index score (n = 5), and lifestyle behaviors (n = 5).

P < 0.001.

Fisher exact test for cell sizes <5. Two-sided P values.

P < 0.050.

P < 0.010.

Appendix Table 3.

Characteristics of Infants Born to Women With GDM, by Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery*

| Characteristic | Exclusive Formula (n = 153) |

Mostly Formula, Mixed/Inconsistent (n = 214) |

Mostly Lactation (n = 387) |

Exclusive Lactation (n = 205) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean birthweight (SD), g† | 3435 (478.9) | 3426 (495.7) | 3355 (523.5) | 3470 (460.6) |

| Mean length (SD), cm† | 50.5 (2.5) | 51.0 (2.4) | 50.3 (2.5) | 50.7 (2.4) |

| Mean weight for length Z score (SD)† | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.5 (1.3) | −0.3 (1.4) | −0.2 (1.3) |

| Median weight for length Z score† | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.6) | −0.5 (−1.4 to 0.2) | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.6) | −0.2 (−1.1 to 0.8) |

| Sex, n (%)† | ||||

| Female | 76 (49.7) | 81 (37.8) | 192 (49.6) | 103 (50.2) |

| Male | 77 (50.3) | 133 (62.2) | 195 (50.4) | 102 (49.8) |

| Gestational age, n (%)ठ| ||||

| 35 to <37 wk (preterm) | 6 (3.9) | 5 (2.3) | 29 (7.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| ≥37 wk (term) | 147 (96.1) | 209 (97.7) | 358 (92.5) | 201 (98.0) |

| Birthweight, n (%)†‡ | ||||

| 1500–2499 g | 3 (2.0) | 2 (0.9) | 18 (4.7) | 3 (1.5) |

| 2500–2999 g | 26 (17.0) | 38 (17.8) | 85 (22.0) | 27 (13.2) |

| 3000–3999 g | 108 (70.5) | 150 (70.1) | 241 (62.2) | 152 (74.1) |

| ≥4000 g | 16 (10.5) | 24 (11.2) | 43 (11.1) | 23 (11.2) |

| Birth size for gestational age, n (%)‡ | ||||

| Small | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.3) | 9 (2.3) | 3 (1.5) |

| Appropriate | 119 (77.8) | 161 (75.2) | 293 (75.7) | 157 (76.6) |

| Large | 34 (22.2) | 46 (21.5) | 85 (22.0) | 45 (22.0) |

| Apgar score at 5 min, n (%)‡ | ||||

| ≤6 | 1 (0.7) | 4 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥7 | 149 (97.3) | 209 (97.6) | 377 (97.4) | 201 (98.0) |

| Missing | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (1.6) | 4 (2.0) |

| Newborn nursery, n (%)ठ| ||||

| NICU | 10 (6.5) | 11 (5.1) | 22 (5.7) | 2 (1.0) |

| Brief/intermediate level | 10 (6.5) | 21 (9.8) | 26 (6.7) | 4 (2.0) |

| Well care | 133 (86.9) | 182 (85.1) | 339 (87.6) | 199 (97.1) |

| Hospital stay, n (%)† | ||||

| ≥3 d | 37 (24.2) | 48 (22.4) | 77 (19.9) | 27 (13.2) |

| <3 d | 116 (75.8) | 166 (77.6) | 310 (80.1) | 178 (86.8) |

GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; IQR = interquartile range; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Study baseline. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables; F test was used for continuous variables. Kruskal–Wallis test for comparison of medians. Two-sided P values.

P < 0.050.

Fisher exact test for cell sizes <5.

P < 0.010.

Appendix Table 4.

Distribution of 959 SWIFT Participants Among Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery and Lactation Duration Groups at the End of Follow-up*

| Lactation Intensity Groups at 6 to 9 wk After Delivery (Baseline) |

Lactation Duration Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 mo | >2–5 mo | >5–10 mo | >10 mo | Total | |

| Exclusive lactation | 2 (0.2) | 20 (2.1) | 45 (4.7) | 138 (14.4) | 205 (21.4) |

| Mostly lactation (≤6 oz of formula per day) | 5 (0.5) | 73 (7.6) | 116 (12.1) | 193 (20.1) | 387 (40.3) |

| Mostly formula feeding (>17 oz of formula per day) and mixed/inconsistent lactation | 29 (3.0) | 97 (10.1) | 47 (4.9) | 41 (4.3) | 214 (22.3) |

| Exclusive formula feeding | 153 (16.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 153 (16.0) |

| Overall total | 189 (19.7) | 190 (19.8) | 208 (21.7) | 372 (38.8) | 959 (100) |

SWIFT = Study of Women, Infant Feeding, and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy.

P < 0.001. Values are numbers (percentages).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M15-0807.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol, statistical code, and data set: Available from Dr. Gunderson (Erica.Gunderson@kp.org).

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: E.P. Gunderson, C.P. Quesenberry.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: E.P. Gunderson, S.R. Hurston, X. Ning, J.C. Lo, D. Walton, B. Sternfeld, C.P. Quesenberry.

Drafting of the article: E.P. Gunderson.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: E.P. Gunderson, J.C. Lo, D. Walton, K.G. Dewey, B. Sternfeld.

Final approval of the article: E.P. Gunderson, S.R. Hurston, X. Ning, J.C. Lo, Y. Crites, D. Walton, K.G. Dewey, R.A. Azevedo, S. Young, G. Fox, C.C. Elmasian, N. Salvador, M. Lum, B. Sternfeld, C.P. Quesenberry.

Provision of study materials or patients: E.P. Gunderson, Y. Crites, D. Walton, S. Young, C.C. Elmasian, N. Salvador, M. Lum.

Statistical expertise: C.P. Quesenberry.

Obtaining of funding: E.P. Gunderson, C.P. Quesenberry.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: S.R. Hurston, J.C. Lo, K.G. Dewey, G. Fox, C.C. Elmasian.

Collection and assembly of data: E.P. Gunderson, S.R. Hurston, J.C. Lo.

References

- 1.DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E104. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130415. [PMID: 24945238] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [PMID: 19465232] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [PMID: 11832527] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albright AL, Gregg EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the U.S.: the National Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:S346–S351. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.009. [PMID: 23498297] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunderson EP, Hedderson MM, Chiang V, Crites Y, Walton D, Azevedo RA, et al. Lactation intensity and postpartum maternal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in women with recent GDM: the SWIFT cohort. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:50–56. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1409. [PMID: 22011407] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunderson EP, Kim C, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Marcovina S, Walton D, Azevedo RA, et al. Lactation intensity and fasting plasma lipids, lipoproteins, non-esterified free fatty acids, leptin and adiponectin in postpartum women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: the SWIFT cohort. Metabolism. 2014;63:941–950. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.04.006. [PMID: 24931281] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knopp RH, Walden CE, Wahl PW, Bergelin R, Chapman M, Irvine S, et al. Effect of postpartum lactation on lipoprotein lipids and apoproteins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:542–547. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-3-542. [PMID: 3972965] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tigas S, Sunehag A, Haymond MW. Metabolic adaptation to feeding and fasting during lactation in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:302–307. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8178. [PMID: 11788664] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McManus RM, Cunningham I, Watson A, Harker L, Finegood DT. Beta-cell function and visceral fat in lactating women with a history of gestational diabetes. Metabolism. 2001;50:715–719. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.23304. [PMID: 11398150] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi IA, Xi XR, Limbu YR, Bin HY, Chen MI. Hyperlipidaemia during normal pregnancy, parturition and lactation. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28:217–221. [PMID: 10497670] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Wei GS, Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Sidney S. Lactation and changes in maternal metabolic risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:729–738. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000252831.06695.03. [PMID: 17329527] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunderson EP, Jacobs DR, Jr, Chiang V, Lewis CE, Feng J, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Duration of lactation and incidence of the metabolic syndrome in women of reproductive age according to gestational diabetes mellitus status: a 20-year prospective study in CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) Diabetes. 2010;59:495–504. doi: 10.2337/db09-1197. [PMID: 19959762] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjos SL, Henry O, Lee RM, Buchanan TA, Mishell DR., Jr The effect of lactation on glucose and lipid metabolism in women with recent gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:451–455. [PMID: 8355952] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;294:2601–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.20.2601. [PMID: 16304074] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villegas R, Gao YT, Yang G, Li HL, Elasy T, Zheng W, et al. Duration of breast-feeding and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Shanghai Women's Health Study. Diabetologia. 2008;51:258–266. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0885-8. [PMID: 18040660] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegler AG, Wallner M, Kaiser I, Rossbauer M, Harsunen MH, Lachmann L, et al. Long-term protective effect of lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2012;61:3167–3171. doi: 10.2337/db12-0393. [PMID: 23069624] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunderson EP, Matias SL, Hurston SR, Dewey KG, Ferrara A, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Study of Women, Infant Feeding, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus after GDM pregnancy (SWIFT), a prospective cohort study: methodology and design. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:952. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-952. [PMID: 22196129] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(Suppl 1):S4–S19. [PMID: 12017675] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rifas-Shiman SL, Willett WC, Lobb R, Kotch J, Dart C, Gillman MW. PrimeScreen, a brief dietary screening tool: reproducibility and comparability with both a longer food frequency questionnaire and biomarkers. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:249–254. doi: 10.1079/phn200061. [PMID: 11299098] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1750–1760. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142303.49306.0d. [PMID: 15595297] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sparling YH, Younes N, Lachin JM, Bautista OM. Parametric survival models for interval-censored data with time-dependent covariates. Biostatistics. 2006;7:599–614. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj028. [PMID: 16597670] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matias SL, Dewey KG, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Gunderson EP. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and insulin treatment during pregnancy are independently associated with delayed lactogenesis in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:115–121. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073049. [PMID: 24196401] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jäger S, Jacobs S, Kröger J, Fritsche A, Schienkiewitz A, Rubin D, et al. Breast-feeding and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1355–1365. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3247-3. [PMID: 24789344] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B, Jorm L, Banks E. Parity, breastfeeding, and the subsequent risk of maternal type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1239–1241. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0347. [PMID: 20332359] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz EB, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Stuebe A, McClure CK, Van Den Eeden SK, et al. Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Am J Med. 2010;123:863.e1–863.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.016. [PMID: 20800156] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [PMID: 11333990] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butte NF, King JC. Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:1010–1027. doi: 10.1079/phn2005793. [PMID: 16277817] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClure CK, Schwarz EB, Conroy MB, Tepper PG, Janssen I, Sutton-Tyrrell KC. Breastfeeding and subsequent maternal visceral adiposity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2205–2213. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.185. [PMID: 21720436] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rebuffé-Scrive M, Enk L, Crona N, Lönnroth P, Abrahamsson L, Smith U, et al. Fat cell metabolism in different regions in women. Effect of menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and lactation. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1973–1976. doi: 10.1172/JCI111914. [PMID: 4008649] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewey KG. Impact of breastfeeding on maternal nutritional status. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:91–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_9. [PMID: 15384569] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butte NF, Hopkinson JM. Body composition changes during lactation are highly variable among women. J Nutr. 1998;128:381S–385S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.381S. [PMID: 9478031] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin JE, Hure AJ, Macdonald-Wicks L, Smith R, Collins CE. Predictors of post-partum weight retention in a prospective longitudinal study. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10:496–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00437.x. [PMID: 22974518] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neville CE, McKinley MC, Holmes VA, Spence D, Woodside JV. The relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum weight change—a systematic review and critical evaluation. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38:577–590. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.132. [PMID: 23892523] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos-Román MA. Prolactin and lactation as modifiers of diabetes risk in gestational diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2011;43:593–600. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284353. [PMID: 21823053] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drynda R, Peters CJ, Jones PM, Bowe JE. The role of non-placental signals in the adaptation of islets to pregnancy. Horm Metab Res. 2015;47:64–71. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395691. [PMID: 25506682] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandebourg T, Hugo E, Ben-Jonathan N. Adipocyte prolactin: regulation of release and putative functions. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:464–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00671.x. [PMID: 17587388] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butte NF, Hopkinson JM, Nicolson MA. Leptin in human reproduction: serum leptin levels in pregnant and lactating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:585–589. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3731. [PMID: 9024259] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asai-Sato M, Okamoto M, Endo M, Yoshida H, Murase M, Ikeda M, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in lean lactating women: Prolactin inhibits adiponectin secretion from human adipocytes. Endocr J. 2006;53:555–562. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k06-026. [PMID: 16849835] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Shin HJ, Ding EL, van Dam RM. Adiponectin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:179–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.976. [PMID: 19584347] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuebe AM, Mantzoros C, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman S, Gunderson EP, et al. Duration of lactation and maternal adipokines at 3 years postpartum. Diabetes. 2011;60:1277–1285. doi: 10.2337/db10-0637. [PMID: 21350085] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuebe AM, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gunderson EP, Rich-Edwards J. Duration of lactation and maternal metabolism at 3 years postpartum. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:941–950. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1660. [PMID: 20459331] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metzger BE, Cho NH, Roston SM, Radvany R. Prepregnancy weight and antepartum insulin secretion predict glucose tolerance five years after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1598–1605. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.12.1598. [PMID: 8299456] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [PMID: 22371471] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, de Leiva A, Dunger DB, Hadden DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S251–S260. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225. [PMID: 17596481] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 2002–2012, CDC National Immunization Survey. [14 November 2014]; Accessed at www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm on.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.