Abstract

Purpose

Using multiple imaging modalities we evaluated the changes in photoreceptor cells and RPE that are associated with bone spicule-shaped melanin pigmentation in retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Methods

In a cohort of 60 RP patients, short-wavelength autofluorescence (SW-AF), near-infrared (NIR)-AF, NIR-reflectance (NIR-R), spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and color fundus images were studied.

Results

Central AF rings were visible in both SW-AF and NIR-AF images. Bone spicule pigmentation was non-reflective in NIR-R, hypoautofluorescent with SW-AF and NIR-AF imaging and presented as intraretinal hyperreflective foci in SD-OCT images. In areas beyond the AF ring outer border, the photoreceptor ellipsoid zone (EZ) band was absent in SD-OCT scans and the visibility of choroidal vessels in SW-AF, NIR-AF and NIR-R images was indicative of reduced RPE pigmentation. Choroidal visibility was most pronounced in the zone approaching peripheral areas of bone spicule pigmentation; here RPE/Bruch’s membrane thinning became apparent in SD-OCT scans.

Conclusions

These findings are consistent with a process by which RPE cells vacate their monolayer and migrate into inner retina in response to photoreceptor cell degeneration. The remaining RPE spread, undergo thinning and consequently become less pigmented. An explanation for the absence of NIR-AF melanin signal in relation to bone spicule pigmentation is not forthcoming.

Keywords: retinitis pigmentosa, retinal pigment epithelium, melanin pigment, photoreceptor cells, retinal degeneration

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a genetic heterogeneous disease that can be inherited as autosomal-dominant (about 30–40% of cases), autosomal-recessive (50–60%) or X-linked (5–15%)1, 2 traits. An autosomal dominant (ADRP) subgroup of RP is caused in 25% of the cases by a mutation in the rhodopsin gene (RHO). In approximately 20% of cases, autosomal recessive RP (ARRP) is associated with a mutation in the USH2A gene and X-linked RP is causative in 70% of patients by a mutation in the RPGR (retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator) gene. Many other genes are involved in the genesis of each type of RP, however there are a large percentage of cases in which the genetic cause is unknown.

The disease generally starts in the periphery of the retina and progresses centrally resulting in a tunnel-like field of vision. The inner nuclear layer and the ganglion cell layer are usually well preserved in early stages of the disease, but degenerate later.2 The most characteristic fundus findings in RP patients are retinal vessel attenuation, and a pale waxy optic nerve head.2 Especially in the later stages of RP, aberrant aggregations of melanin pigment-containing cells can be visible in the mid-peripheral or far periphery of the fundus. These pigmentary changes are typically described as assuming the shape of bone-spicules.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has shown, as expected, that thinning of outer retina precedes that of inner retina3 and spectral domain (SD)-OCT has demonstrated that diminishing best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) corresponds to the loss of ELM, IS/OS and ONL.4 In SW-AF images wherein the signal originates primarily from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) lipofuscin5, a ring or arc of high AF is often visible within the transitional zone between degenerated and intact photoreceptor cells.6–17 The inner border of the ring delimits an area interior to the ring that exhibits normal function18 and a preserved hyperreflective band attributable to the ellipsoid zone (EZ) on SD-OCT.11 Across the ring visual sensitivity was found to be normal while external to the ring visual sensitivity was profoundly reduced.11 Studies employing SW-AF have demonstrated that AF rings may constrict over time.14, 17 The high AF ring in RP is also visible with NIR-AF imaging;19 this modality employs an excitation light of 787 nm and generates a signal from RPE and choroidal melanin.20 The location of the outer border of the ring was found to be similar in both SW-AF and NIR-AF images although the inner border of the ring was closer to the fovea in the NIR-AF images and corresponded to the position in SD-OCT scans where the EZ band was at least partially intact.11 Interestingly, in patients presenting with NR2E3-p.G56R-linked (nuclear receptor 2E3) autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (ADRP), two concentric hyperautofluorescent rings have been described.21

Since RP patients present with a higher incidence of cataracts than in the healthy population, near infrared reflectance (NIR-R) has been helpful for the study of RP as these wavelengths can better penetrate optical media opacities.2 This modality revealed the presence of a tapetal reflex in carriers of X-linked RP.22

The AF signal generated at the position of rings in RP remains visible after bleaching of photopigment;23 this observations excludes a window defect, emanating from RPE cells that are unobstructed by degenerated photoreceptors, as an explanation for these AF rings. Others have suggested that the abnormal AF from the ring derives from the accelerated phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments.17, 24, 25 However the rate of bisretinoid fluorophore formation is predetermined in photoreceptors prior to outer segment shedding and subsequent phagocytosis. We have previously presented data indicating that disease-related SW-AF patterns are indicative of an accelerated lipofuscin synthetic pathway initiated in disabled photoreceptor cells unable to detoxify excess retinaldehyde of the visual cycle.26, 27

The purpose of this study was to use current multiple imaging modalities to evaluate the characteristics of pigmentary changes in RP so as to better understand the degenerative processes underlying the disease. The evaluation of RPE cells in RP is essential to the assessment of future therapeutic outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Clinical Evaluation

All patients presented in this study were consented under clinical research protocols AAAB6560 and AAAM5813 approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All study procedures adhered to the tenets laid out by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Complete ophthalmic examinations were performed in all patients by a retina specialist (SHT), which included a dilated (Tropicamide 1% and Phenylephrine 2.5%) slit-lamp fundus exam, measurement of best-corrected visual acuity and multi-modal retinal imaging. Diagnostic criteria of RP consisted of typical fundus features and symptoms, family history and, if available, full-field electroretinogram (ffERG) results. Patients with poor or uninterpretable clinical data were also excluded.

Multi-Modal Retinal Image Acquisition and Analysis

Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans and corresponding fundus images were acquired with a Spectralis HRA+OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Horizontal single line (9 mm, ART, average of a minimum of 50 images) SD-OCT scans though the fovea were acquired in high resolution mode. Additionally high resolution volume scans (at least 6mm, 19 scans, ART 9 images averaged, 250µm distance between B-scans, or higher) were acquired in all cases. If pigmentary changes were not visible in the central 30° field, images of retinal periphery were acquired. Fundus images (30° and 50°) acquired with the Spectralis HRA+OCT included near infrared reflectance (NIR-R) and short wavelength autofluorescence (SW-AF, 488-nm excitation).

Near infrared autofluorescence (NIR-AF) images were obtained using a confocal scanning-laser ophthalmoscope (cSLO, Heidelberg Retina Angiograph 2, Heidelberg Engineering, Dossenheim, Germany). All images were acquired in “normalization mode” by a skilled operator ensuring complete illumination of the fundus and optimum focus. Color and red free fundus photos (30 and 55°) were obtained with a FF 450plus Fundus Camera (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany).

Post-acquisitional registration of multi-modal fundus images was performed using the i2k retina software (DualAlign LLC, Clifton Park, NY) allowing for point-by-point correlation of localized changes between modalties. Fundus images and SD-OCT scans were acquired simultaneously with Spectralis HRA+OCT thereby allowing automatic alignment by the hardware-supported HEYEX software.

Multivariate regression was performed using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Version 15.0.4) Analysis ToolPak.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study cohort (n=60) are summarized in Table 1. Mean cohort age was 36.3 years and ranged from 7 to 77 years. A majority of patients (n=30) exhibited best-corrected visual acuities (Snellen) of 20/25 or better while in the rest of the cohort values varied widely (20/30 to HM). Familial inheritance was assessed in all patients at the time of examination with the following results: autosomal dominant (AD), 33%; autosomal recessive (AR), 52%; X-linked recessive (XL), 7% and 8% unknown. Genetic information was available in 23 patients. Amongst AR patients, 5 were clinically diagnosed with Usher 2 syndrome; USH2A mutations were confirmed in 2 (P4 and 33). Other confirmed AR cases included: CNGB1 (P6, P32), KIAA1546 (P14), GPR98 (P22), EYS (P35), RGR (P36), PDE6A (P46) and FAM161B (P50). Mutations in rhodopsin (RHO) was most prevalent in those of AD inheritance (P5, P16, P49 and P58) while singles cases of the following were identified: RP1 (P11, P25), PRPF31 (P26), RP1L1 (P48) and KLHL1 (P51). Mutations in RPGR were confirmed in 4 patients (P29, P30, P38 and P44) of XL inheritance.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic, Clinical and Genetic Data

| Patient | Eye | Sex | Age | Ethnicity | Inheritance | BCVA OD (Snellen) |

BCVA OS (Snellen) |

Gene | Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Mutation 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OU | F | 15 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 2 | OU | F | 28 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 3 | OU | F | 54 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 4 | OU | M | 21 | Caucasian | AR | 20/40 | 20/40 | USH2A | p.T1238R | p.C3153* | |

| 5 | OD | M | 52 | Caucasian | AD | 20/30 | HM | RHO | D190N | ||

| 6† | OU | F | 25 | Hispanic | AR | 20/25 | 20/30 | CNGB1 | p.F1051Lfs*12 | p.F1051Lfs*12 | |

| 7 | OU | F | 53 | Caucasian | AR | 20/30 | 20/50 | ||||

| 8 | OS | M | 37 | Caucasian | AD | 20/50 | 20/25 | ||||

| 9 | OS | M | 7 | Hispanic | AR | 20/50 | 20/30 | ||||

| 10 | OU | F | 11 | Hispanic | AR | 20/25 | 20/25 | ||||

| 11 | OU | M | 59 | Caucasian | AD | 20/25 | 20/25 | RP1 | c.2285_2289delTAAAT | ||

| 12 | OU | M | 50 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 13 | OU | M | 22 | Caucasian | AR | 20/25 | 20/20 | ||||

| 14 | OD | M | 32 | Indian | AR | 20/30 | 20/20 | KIAA1549 | p.Y120A | p.S642L | |

| 15 | OD | F | 33 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 16 | OU | F | 16 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | RHO | c.937-27_-19delCCCTGACTC | ||

| 17 | OU | M | 20 | Hispanic | AR | 20/25 | 20/25 | ||||

| 18 | OD | F | 31 | Asian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 19 | OU | M | 33 | Hispanic | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 20 | OU | F | 32 | Asian | AR | 20/25 | 20/20 | ||||

| 21 | OU | M | 56 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/25 | ||||

| 22 | OD | M | 21 | Caucasian | AR | 20/25 | 20/40 | GPR98 | p.Q2301* | p.Q2301* | |

| 23 | OU | M | 68 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 24 | OU | M | 38 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 25 | OU | M | 29 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/25 | RP1 | p.R667* | ||

| 26 | OU | F | 18 | Caucasian | AD | 20/25 | 20/25 | PRPF31 | p.L128* | ||

| 27 | OS | F | 38 | Caucasian | unknown | 20/25 | 20/25 | ||||

| 28 | OU | M | 61 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 29 | OU | M | 30 | Caucasian | XL | 20/30 | 20/40 | RPGR | p.Q732RfsX83 | ||

| 30 | OU | M | 13 | Caucasian | XL | 20/30 | 20/30 | RPGR | p.G436D | ||

| 31 | OU | M | 14 | Caucasian | AD | 20/30 | 20/40 | ||||

| 32† | OU | M | 22 | Hispanic | AR | 20/25 | 20/25 | CNGB1 | p.F1051Lfs*12 | p.F1051Lfs*12 | |

| 33 | OU | M | 57 | Caucasian | AR | 20/25 | 20/50 | USH2A | |||

| 34 | OU | M | 64 | Caucasian | unknown | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 35 | OU | M | 51 | Asian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | EYS | p.L2671Y | p.C2139Y | p.S547Rfs |

| 36 | OU | F | 31 | Caucasian | AR | 20/40 | 20/40 | RGR | p.S66R | p.S66R | |

| 37 | OU | F | 57 | Caucasian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 38 | OU | M | 16 | Indian | XL | 20/25 | 20/40 | RPGR | p.G68R | ||

| 39 | OU | F | 77 | Caucasian | AR | 20/25 | 20/30 | ||||

| 40 | OD | M | 43 | Caucasian | AD | 20/50 | 20/63 | ||||

| 41 | OU | M | 15 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 42 | OU | M | 19 | Caucasian | AD | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 43 | OU | F | 32 | Asian | AR | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 44 | OU | M | 44 | Hispanic | XL | 20/80 | 20/63 | RPGR | c.2236_2237delAG | ||

| 45 | OU | M | 30 | Caucasian | AR | 20/30 | 20/25 | ||||

| 46 | OU | M | 37 | Hispanic | AR | 20/50 | 20/40 | PDE6A | p.R102C | p.S303C | |

| 47 | OD | F | 11 | African American | AR | 20/30 | 20/25 | ||||

| 48 | OD | F | 53 | Caucasian | AD | 20/40 | 20/40 | RP1L1 | c.5334_5335delAC | ||

| 49 | OU | M | 75 | Caucasian | AD | 20/50 | 20/40 | RHO | p.G106R | ||

| 50 | OU | F | 28 | Caucasian | AR | 20/50 | 20/80 | FAM161B | p.V707YfsX9 | * | |

| 51 | OU | F | 35 | Caucasian | AD | 20/30 | 20/25 | KLHL7 | p.N145Y | ||

| 52 | OU | F | 49 | Caucasian | AR | 20/63 | 20/80 | ||||

| 53 | OU | F | 31 | Caucasian | unknown | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 54 | OU | M | 46 | Asian | AR | 20/50 | 20/20 | ||||

| 55 | OU | F | 19 | Caucasian | AR | 20/25 | 20/25 | ||||

| 56 | OU | F | 43 | Caucasian | unknown | 20/20 | 20/20 | ||||

| 57 | OU | F | 58 | Caucasian | AR | 20/50 | 20/160 | ||||

| 58 | OU | F | 36 | Caucasian | AD | 20/30 | 20/25 | RHO | p.R135I | p.R135R | |

| 59 | OU | M | 38 | Caucasian | unknown | 20/40 | 20/40 | ||||

| 60 | OU | M | 43 | Hispanic | AD | 20/50 | 20/20 |

BCVA, best corrected visual acuity; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive: XL, X-linked,

indicates stop codon.

denotes sibling pair: P6 and P23

Multimodal Imaging

All patients exhibited canonical features associated with retinitis pigmentosa including attenuated arterioles, waxy disc palor (Figure 1). In the SD-OCT cystoid macular edema was found in 11 patients. Notably, bone spicule pigment migration, in varying degrees of confluence, was evident on fundoscopy and color fundus photography in the peripheral regions of 27 patients. Bone spicules were less apparent in SW-AF images of 3 patients because the pigment-associated shadowing overlapped with areas of reduced SW-AF signal due to advanced atrophy. Cross-imaging analyses of the pigment revealed that it was non-reflective in NIR-R and hypoautofluorescent with SW-AF and NIR-AF imaging (Figure 1). SD-OCT scans through the pigmented areas revealed corresponding hyper-reflective aggregations in inner retina and less frequently in ONL (Figure 2, B, D, H). Visibility in color fundus photographs, NIR-R and NIR-AF images depended on the size of the pigment aggregations and the extent of hyper-reflectivity in inner retina; however, intraretinal pigment was always discernible in SW-AF images as areas of reduced signal (Figure 2E).

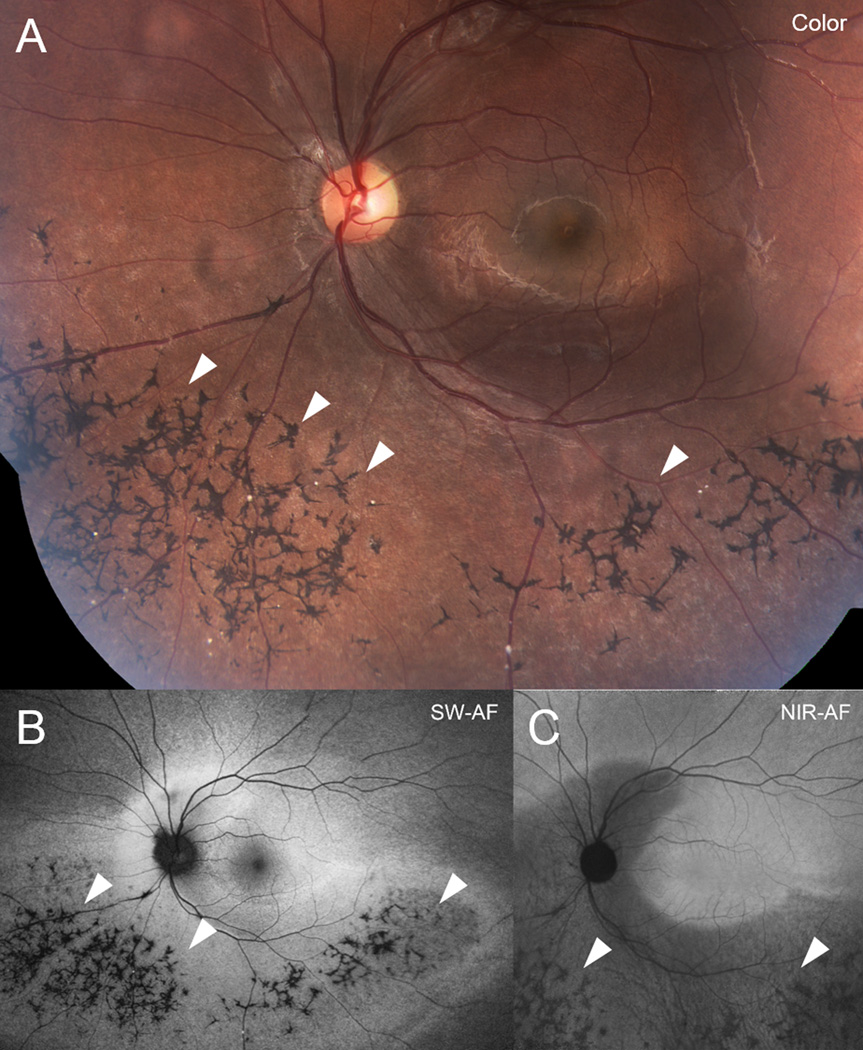

Figure 1.

Bone spicule-like intraretinal pigment aggregation in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (P17). Color montage (A), short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (SW-AF) (B) and near-infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIR-AF) (C) images. Bone spicule pigmentary changes (arrow heads) visible in color fundus photography are not autofluorescent in SW-AF and NIR-AF images.

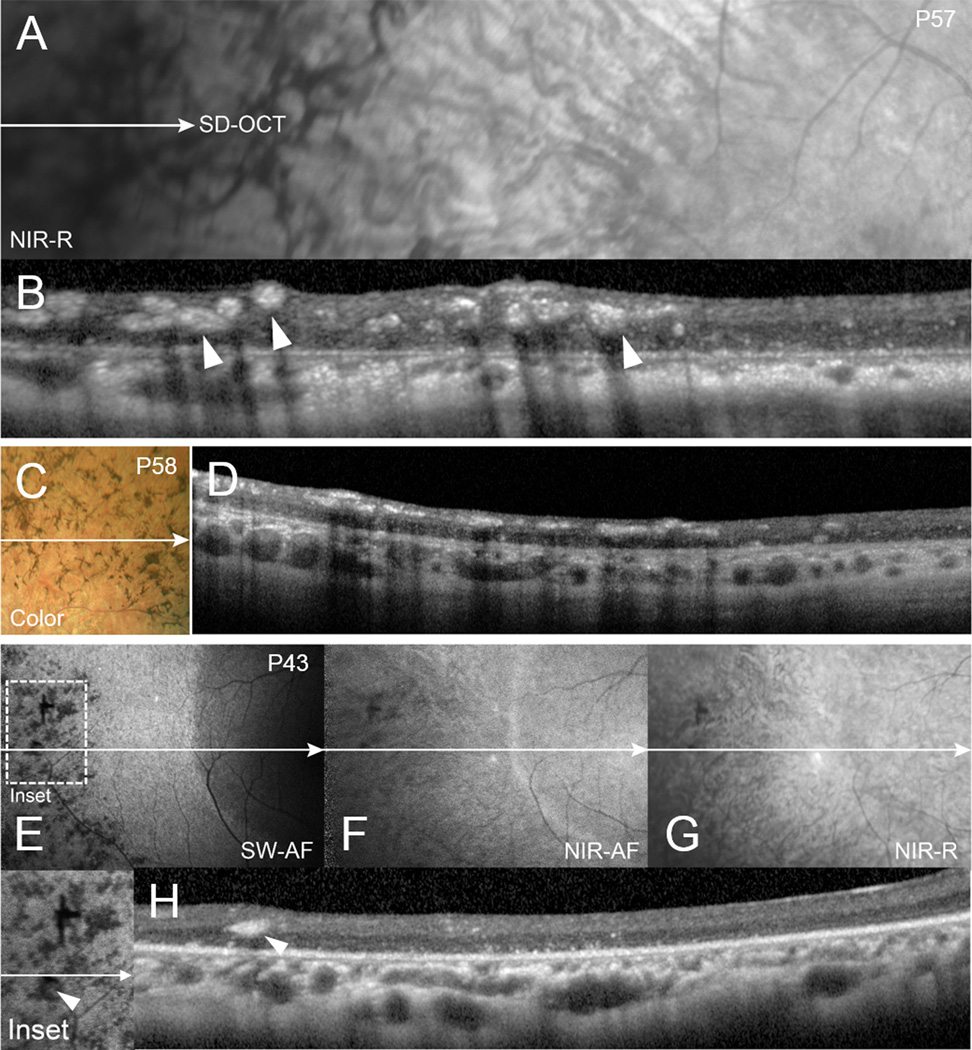

Figure 2.

Multi-modal fundus imaging and corresponding SD-OCT of bone-spicule pigment migration of RP patients (P57, P58 and P43). Near-infrared reflectance (NIR-R) (A,G), spectral domain optical coherent tomography (SD-OCT) (B, D, H), color fundus photography (C), short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (SW-AF) (E) and near-infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIR-AF) (F). The horizontal axis and extent of SD-OCT scans is indicated by white lines with single arrows in the fundus images. The intraretinal hyperreflective cellular deposits (arrow heads) generate a shadow-effect in the SD-OCT and corresponding darkness in the SW-AF image. NIR-AF intensity is diminished with increased eccentricity.

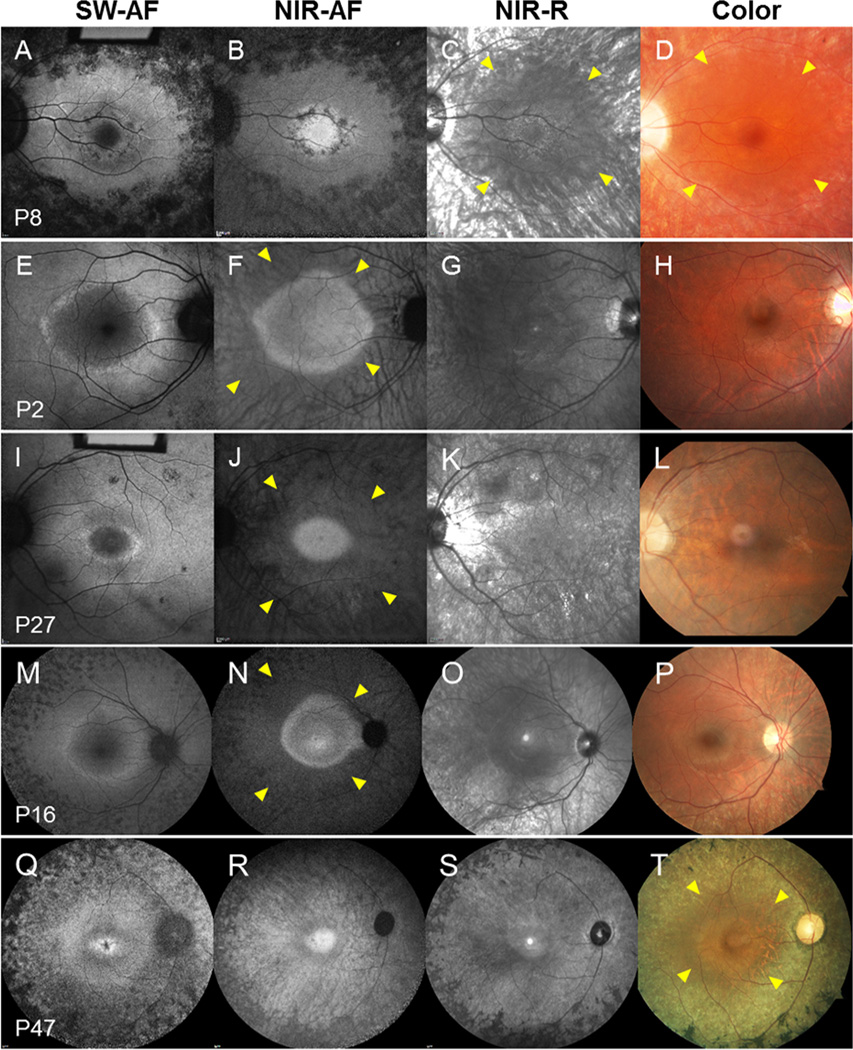

Central AF rings of variable size, typically round or elliptical in shape, were best visualized in SW-AF and NIR-AF images (Figure 3). A hyperfluorescent ring was found in 85% (51/60) of patients in SW-AF images. Distinct inner and outer borders of the ring were discernable with SW-AF in 80% (48/60) of patients while in 38% (23/60) of patients only an outer border was apparent in NIR-AF images (Table 2 and Figure 3). In SD-OCT scans, the hyper-reflective, photoreceptor-attributable ellipsoid zone (EZ) terminated at a position that corresponded to the outer borders of the rings in both SW-AF and NIR-AF images (Figure 4 only NIR-AF shown). Regions beyond the ring outer border exhibited characteristics of advanced atrophy: hypopigmentation and choroidal vessel visibility in SW-AF, NIR-AF and NIR-R images, hyperreflective foci in SD-OCT images and spicular pigmentation in color and NIR-R images (Figures 2 and 3). Interestingly, in a large proportion of patients (n=46) the region outside and adjacent to the outer border of the ring appeared less hypopigmented relative to more peripheral atrophied areas; here choroidal vessels were somewhat obscured (Figure 3 yellow arrows; Figure 4, blue lines). This finding was most evident in color, NIR-R and NIR-AF images. Moreover, the outer edge of this region was found to correlate with abrupt thinning of the RPE/Bruch’s membrane attributable reflectivity band along with severe delamination of the inner and outer retina on SD-OCT (Figure 4, at transition between blue line (horizontal and vertical) and no line). Hypopigmentation in color photography or NIR-R images was noted in all 60 patients. In 59 of these patients the hypopigmentation corresponded to hypoautofluorescence in NIR-AF images (1 patient did not have NIR-AF). To assess associations between inheritance patterns (AR, AD, XL and unknown) and other described phenotypes (bone spicules, hypoautofluorescence, ring patterns in SW-AF and NIR-AF), a multivariate regression analysis was performed but did not reveal significant associations amongst the groups.

Figure 3.

Representative short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (SW-AF), near-infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIR-AF), near-infrared reflectance (NIR-R) and color fundus images obtained from RP patients. The dotted lines indicate the outer border of the AF ring. Note the appearance of the AF ring in various modalities. Interior to the ring, there is brightness in the NIR-AF image and relative darkness in the SW-AF image. The zone of reduced melanin in the RPE monolayer (yellow arrows) permits choroidal vessel visibility.

Table 2.

comparison of phonotypical features (bone spicules, loss of pigmentation, SW-AF rings and CME) in different imaging modalities with the inheritance pattern for every patient. AR, autosomal recessive; AD, autosomal dominant; XL, X-linked inheritance pattern. CME, cystoid macular edema.

| Patient | Inheritance pattern |

Bone spicules (Color/NIR-R.) |

Loss of pigmentation |

Rings | CME | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color/NIR-R | Color/NIR-R |

SW-AF (hypo- AF) |

OCT (RPE loss) |

SW-AF |

SW-AF (inner/outer border) |

NIR-AF (inner/outer border) |

NIR-AF (outer border only) |

OCT | ||

| 1 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 4 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 5 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 7 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 10 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 11 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 13 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 14 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 16 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 17 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 18 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 19 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 20 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 21 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 22 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 23 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 24 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 25 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 26 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 27 | unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 28 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 29 | XL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 30 | XL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 31 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 32 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 33 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 34 | unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 35 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 36 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 37 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 38 | XL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 39 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 40 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 41 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 42 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 43 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 44 | XL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 45 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 46 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 47 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 48 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 49 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 50 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 51 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 52 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 53 | unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 54 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 55 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 56 | unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 57 | AR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 58 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 59 | unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 60 | AD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

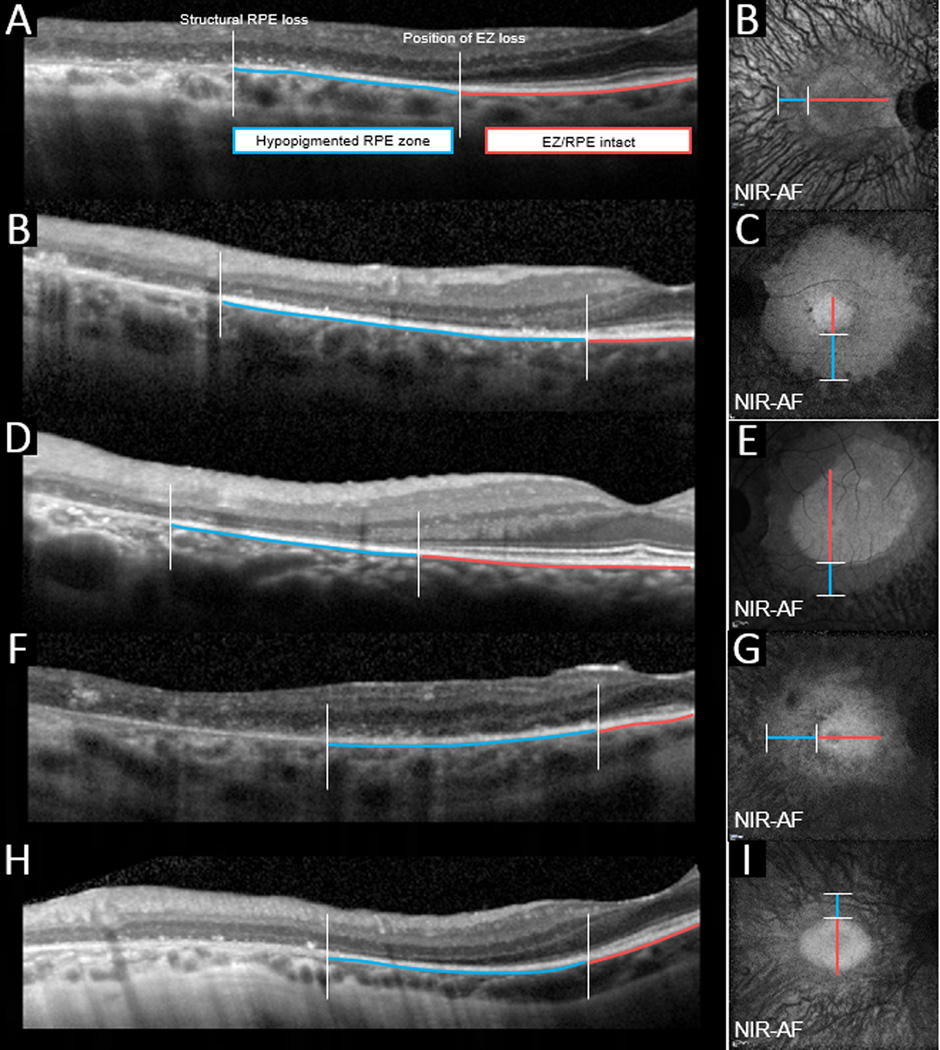

Figure 4.

Horizontal SD-OCT scans (A-H) and corresponding near-infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIR-AF) in P57, P23, P19, P48 and P22. The red lines (horizontal in the SD-OCT images and vertical (horizontal) in the fundus images) mark the zone where the ellipsoid zone (EZ) and RPE/Bruch’s bands are intact. The blue lines demarcate the zones where the EZ band is absent. The horizontal lines in A-H are placed below the reflectivity bands attributable to RPE/Bruch’s membrane in the SD-OCT images. Within the zones indicated by the blue lines, reduced pigmentation is apparent in color fundus, NIR-R and NIR-AF images. The latter aberration is more pronounced in the zones peripheral to the blue lines.

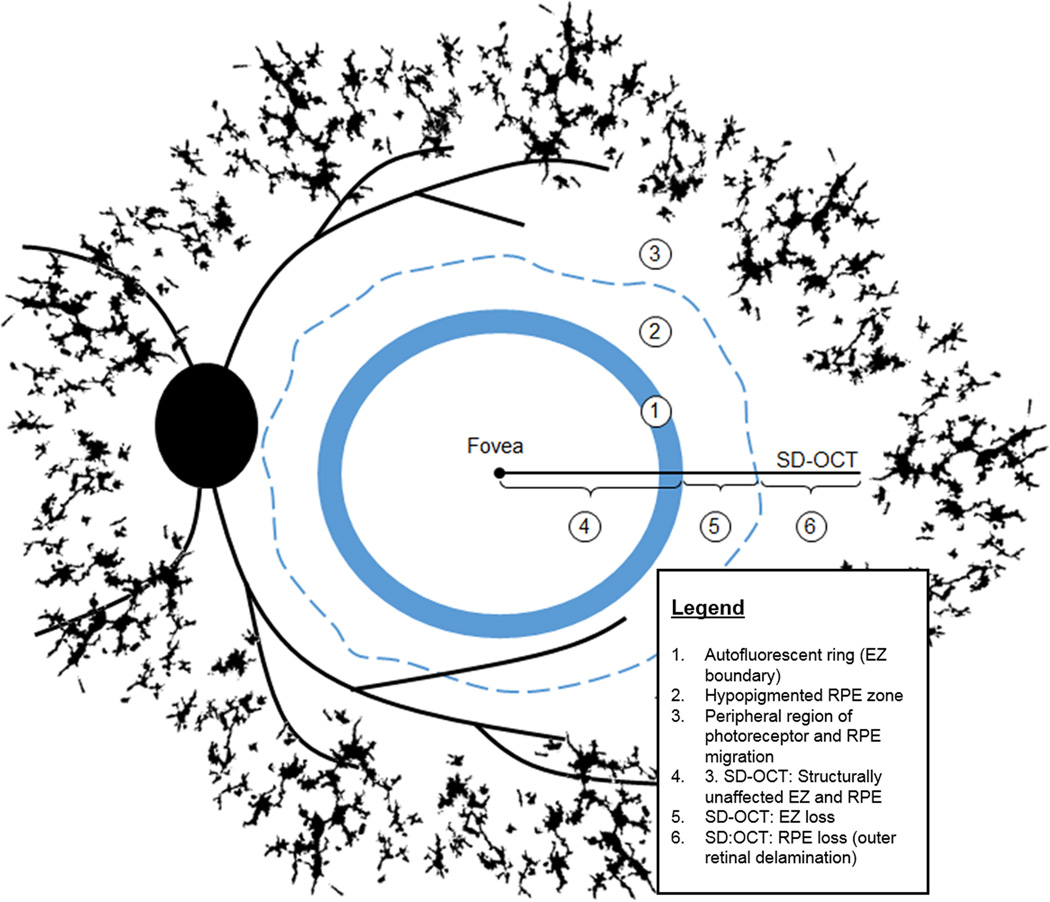

Figure 5 summarizes the changes deduced by correlating information obtained by multimodal imaging of RP patients. The inner border of the AF ring (Figure 5; 1) demarcates a healthy area having intact inner and outer retinal layers on SD-OCT (Figure 5; 4). In the region adjacent to the outer border of the ring (Figure 5; 5) the choroidal vessels were faintly visible in color and NIR-R images and in SD-OCT images this position was defined by an absence of the EZ band but apparently intact RPE/Bruch’s membrane. Regions more distant in the periphery were characterized by visibility of choroidal vessels, presence of migratory pigment, AF foci (n=32) (Figure 5; 3) and severe inner and outer retinal layer disorganization in SD-OCT images (Figure 5; 6).

Figure 5.

Scheme illustrating changes in the RPE and photoreceptor cells deduced by correlating information obtained by multi-modal imaging of RP patients. Bone spicule pigment in the fundus periphery (black) is populated by translocated RPE cells. The AF ring (1) is visible in both SW-AF and NIR-AF images and the outer border of the ring in NIR-AF and SW-AF images exhibits good correspondence. Outside the ring, changes (e.g. visibility of choroidal vessel) in the NIR-R, NIR-AF and SW-AF images are indicative of reduced RPE pigmentation in the original RPE monolayer (2). Reduced melanin pigmentation in the cells progresses (3) with distance from the AF ring (1). The photoreceptor ellipsoid zone (EZ) visible in SD-OCT images, terminates at the outer border of the AF ring thus creating a zone of EZ absence (5). With greater eccentricity (6) SD-OCT imaging reveals RPE displacement and progressive retinal delamination.

Discussion

Our results obtained with non-invasive imaging are consistent with earlier studies employing light and electron microscopy to examine retinas obtained postmortem from donors with RP.28–30 These authors have described partially de-differentiated melanin-containing RPE cells that have detached from Bruch’s membrane and migrated along blood vessels to inner retina. Accretions of these cells are visible as intraretinal hyperreflective foci in SD-OCT images (Figure 2)31 In some instances it is reported that these migrating RPE cells lack lipofuscin29 while in other cases lipofuscin is present.28 A dearth of lipofuscin would explain the absence of SW-AF signal, as observed here in association with bone spicules. Whether the RPE cells that eventually migrated, had accumulated lipofuscin at one time is not known. If they had, the lipofuscin content could have been diminished by cell division and dilution amongst daughter cells. Indeed, it has been suggested that RPE cells proliferate in RP.32 Nevertheless, the dilution of melanin does not seem to occur during the formation of bone spicules, as the cells forming these aggregations remain heavily pigmented. Mature RPE cells in situ are said to be incapable of melanin synthesis but whether this limitation is also expressed by proliferating and migrating RPE in RP is not known. Unexpectedly and despite their obvious melanin content, bone spicules did not exhibit a NIR-AF signal, only darkness (787 nm excitation) (Figures 1–3). By way of explaining this conundrum, we suggest that the NIR-AF emission may be reduced by self-absorbance of the fluorescence as a result of dense packing of melanosomes.

The outer border of the high AF ring in RP demarcates a transition between degenerating photoreceptor cells and dysfunctional but intact photoreceptor cells. By examining SD-OCT scans at the level of the outer border of the AF ring, we noted that at positions peripheral to EZ loss, the RPE/Bruch’s membrane attributable band is absent or significantly thinned.

Interestingly, this location corresponded to areas of decreased pigmentation and autofluorescence in color fundus, NIR-R and NIR-AF images. This area is sufficiently opaque to diminish the visibility of choroidal vessels that are clearly apparent in more eccentric areas corresponding to apparent RPE loss on SD-OCT. We hypothesize that in this area external but adjacent to the outer ring boundary, RPE cells are structurally present but hypopigmented due to disease-related changes. It is worth noting that bone spicule pigmentation and observed hyper-reflective foci in SD-OCT scans are only present outside this area. We suggest that the hypopigmentation and thinning of RPE occurs secondary to proliferation, spreading and migration of RPE with the formation of bone spicule pigment abnormalities. Just as with the visible thinning of RPE/Bruch’s membrane we observed in SD-OCT images, reports from histological studies have described a flattened RPE monolayer in some zones, absence of RPE in other areas and clumping of dislocated RPE at yet other locations.30, 33

In summary, multimodal imaging using color, NIR-R, NIR-AF, SW-AF and SD-OCT reveals the changing spatial characteristics of RPE cells along the disease trajectory of RP (Figure 5). The AF rings see on SW-AF and NIR-AF delimit an area of functionally and structurally intact retina. In an area immediately outside the external boundary of the ring, RPE cells may be present but hypopigmented, as RPE cells vacate the monolayer and the remaining in situ RPE spread to fill the gaps. The severe retinal disorganization associated with RPE cell migration to inner retina and bone spicule pigmentation occurs beyond this area.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Eye Institute/NIH EY024091, 5P30EY019007, R01EY018213; Foundation Fighting Blindness, Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University, OPOS Foundation, St. Gallen, Switzerland, Alfred-Vogt-Foundation, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Bunker CH, Berson EL, Bromley WC, et al. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in Maine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:357–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vamos R, Tatrai E, Nemeth J, et al. The structure and function of the macula in patients with advanced retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:8425–8432. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia Parodi M, La Spina C, Triolo G, et al. Correlation of SD-OCT findings and visual function in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delori FC, Keilhauer C, Sparrow JR, Staurenghi G. Origin of fundus autofluorescence. In: Holz FG, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Spaide RF, Bird AC, editors. Atlas of Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sujirakul T, Davis R, Erol D, et al. Bilateral Concordance of the Fundus Hyperautofluorescent Ring in Typical Retinitis Pigmentosa Patients. Ophthalmic Genet. 2015;36:113–122. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2013.841962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Huet RA, Collin RW, Siemiatkowska AM, et al. IMPG2-associated retinitis pigmentosa displays relatively early macular involvement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3939–3953. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popovic P, Jarc-Vidmar M, Hawlina M. Abnormal fundus autofluorescence in relation to retinal function in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:1018–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-1186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Huet RA, Siemiatkowska AM, Ozgul RK, et al. Retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the ciliary MAK gene is relatively mild and is not associated with apparent extra-ocular features. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:83–94. doi: 10.1111/aos.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenstein VC, Duncker T, Holopigian K, et al. Structural and functional changes associated with normal and abnormal fundus autofluorescence in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Retina. 2012;32:349–357. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821dfc17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncker T, Tabacaru MR, Lee W, et al. Comparison of near-infrared and short-wavelength autofluorescence in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:585–591. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bocquet B, Marzouka NA, Hebrard M, et al. Homozygosity mapping in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa families detects novel mutations. Mol Vis. 2013;19:2487–2500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncker T, Lee W, Tsang SH, et al. Distinct characteristics of inferonasal fundus autofluorescence patterns in stargardt disease and retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:6820–6826. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen S, Sujirakul T, Tsang SH. Next-generation sequencing revealed a novel mutation in the gene encoding the beta subunit of rod phosphodiesterase. Ophthalmic Genet. 2014;35:142–150. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2014.915328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassuk AG, Sujirakul T, Tsang SH, Mahajan VB. A novel RPGR mutation masquerading as Stargardt disease. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2014;98:709–711. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima LH, Cella W, Greenstein VC, et al. Structural assessment of hyperautofluorescent ring in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Retina. 2009;29:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181ac2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lima LH, Burke T, Greenstein VC, et al. Progressive constriction of the hyperautofluorescent ring in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hood DC, Lazow MA, Locke KG, et al. The transition zone between healthy and diseased retina in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:101–108. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellner U, Kellner S, Weber BH, et al. Lipofuscin- and melanin-related fundus autofluorescence visualize different retinal pigment epithelial alterations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1349–1359. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keilhauer CN, Delori FC. Near-infrared autofluorescence imaging of the fundus: visualization of ocular melanin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3556–3564. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escher P, Tran HV, Vaclavik V, et al. Double concentric autofluorescence ring in NR2E3-p.G56R-linked autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4754–4764. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acton JH, Greenberg JP, Greenstein VC, et al. Evaluation of multimodal imaging in carriers of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Exp Eye Res. 2013;113:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theelen T, Berendschot TT, Boon CJ, et al. Analysis of visual pigment by fundus autofluorescence. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aizawa S, Mitamura Y, Hagiwara A, et al. Changes of fundus autofluorescence, photoreceptor inner and outer segment junction line, and visual function in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:597–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robson AG, Saihan Z, Jenkins SA, et al. Functional characterisation and serial imaging of abnormal fundus autofluorescence in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and normal visual acuity. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2006;90:472–479. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparrow JR, Yoon KD, Wu Y, Yamamoto K. Interpretations of fundus autofluorescence from studies of the bisretinoids of the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4351–4357. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelman R, Chen R, Blonska A, et al. Fundus autofluorescence imaging in a patient with rapidly developing scotoma. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports. 2012;6:345–348. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e318260af5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li ZY, Jacobson SG, Milam AH. Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa caused by the threonine-17-methionine rhodopsin mutation: retinal histopathology and immunocytochemistry. Exp Eye Res. 1994;58:397–408. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li ZY, Possin DE, Milam AH. Histopathology of bone spicule pigmentation in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. 1995;102:805–816. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humayun MS, Prince M, de Juan E, Jr, et al. Morphometric analysis of the extramacular retina from postmortem eyes with retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroda M, Hirami Y, Hata M, et al. Intraretinal hyperreflective foci on spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic images of patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:435–440. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S58164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flannery JG, Farber DB, Bird AC, Bok D. Degenerative changes in a retina affected with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:191–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szamier RB, Berson EL. Retinal histopathology of a carrier of X-chromosome-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]