Abstract

Strong bottom-up impulses and weak top-down control may interactively lead to overeating and, consequently, weight gain. In the present study, female university freshmen were tested at the start of the first semester and again at the start of the second semester. Attentional bias toward high- or low-calorie food-cues was assessed using a dot-probe paradigm and participants completed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Attentional bias and motor impulsivity interactively predicted change in body mass index: motor impulsivity positively predicted weight gain only when participants showed an attentional bias toward high-calorie food-cues. Attentional and non-planning impulsivity were unrelated to weight change. Results support findings showing that weight gain is prospectively predicted by a combination of weak top-down control (i.e. high impulsivity) and strong bottom-up impulses (i.e. high automatic motivational drive toward high-calorie food stimuli). They also highlight the fact that only specific aspects of impulsivity are relevant in eating and weight regulation.

Keywords: attentional bias, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, body mass index, calorie content, dot probe, energy density, food-cues, impulsivity, prospective study, weight gain

Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that eating behavior and, consequently, body weight are determined by an interplay of top-down control processes and bottom-up impulses (Appelhans, 2009; Heatherton and Wagner, 2011). Specifically, studies have shown that individuals with both high impulsivity (as measured by poor motor response inhibition or high preference for immediate reward) and high susceptibility to food-related bottom-up impulses (as measured by implicit preference for food, self-reported food reward sensitivity, or approach bias toward food) exhibit higher intake of palatable foods in the laboratory (Appelhans et al., 2011; Hofmann et al., 2009; Kakoschke et al., 2015a). In other studies, similar interactive effects on outcome measures other than laboratory food intake were observed. For example, poor motor response inhibition in response to high-calorie (HC) food-cues was found in individuals reporting a combination of both high impulsivity and trait food craving (Meule and Kübler, 2014). In a study using neuroimaging, food-cue elicited activity in reward-related brain areas was predictive of higher body mass index (BMI), but only in individuals reporting low self-control (Lawrence et al., 2012).

Despite these converging findings of studies using related, but a variety of methodologies, prospective studies reporting such interactive effects are rare. In one study, Nederkoorn et al. (2010) investigated body weight change over 1 year in female undergraduate students. Implicit preference for snack foods was measured with a single-category implicit association test, and response inhibition was measured with a stop-signal task. It was found that a combination of task performance in both measures prospectively predicted weight change: participants with both strong implicit preference for snack foods and low inhibitory control gained the most weight.

The current study sought to replicate and extend these findings. As a measure of food-related bottom-up processes, a dot-probe task was used for assessing an attentional bias toward HC or low-calorie (LC) foods. Attentional bias refers to selective attentional processing of certain stimuli (Kemps and Tiggemann, 2009; Werthmann et al., 2015). In the current study, an attentional bias toward HC foods was represented by faster reaction times to dots appearing behind HC versus LC food-cues, indicating preferred attention allocation to such cues.

As a measure of (low) top-down control, the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) was used for assessing trait impulsivity. Trait impulsivity can be defined as a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions (Moeller et al., 2001). Yet, impulsivity is a multifaceted construct and with the BIS, for example, three facets can be differentiated representing attentional impulsivity (inability to focus attention or concentrate), motor impulsivity (acting without thinking), and non-planning impulsivity (lack of future orientation or forethought; Stanford et al., 2009). Although both attentional bias toward HC food-cues and impulsivity have been implicated to play a role in the development of overweight and obesity (Guerrieri et al., 2008; Werthmann et al., 2015), prospective studies, which are necessary to determine causal influences, are rare (Calitri et al., 2010; Reinert et al., 2013; Yokum et al., 2011).

Based on previous findings outlined above, it was expected that attentional bias toward HC food-cues and high impulsivity in combination would prospectively predict weight gain in female students. Note, however, that the nature of interactions found across previous studies was inconsistent and, thus, this interactive effect may be additive (Lawrence et al., 2012; Meule and Kübler, 2014) or non-additive (Appelhans et al., 2011; Hofmann et al., 2009; Kakoschke et al., 2015a; Nederkoorn et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants and procedure

This study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2008. Participants were recruited via postings in the Department of Psychology at the University of Würzburg, Germany, which advertised the study as an investigation on the cognitive processing of food pictures. In accordance with similar studies (e.g. Nederkoorn et al., 2010), only women were recruited in order to avoid a possible confounding effect of sex as men and women differ in body mass, eating-related variables, and predictors of weight gain (Holm-Denoma et al., 2008). Fifty-seven female university freshmen provided informed consent and participated in the study. Three participants reported to have a chronic disease (1x thyroid disease, 2x asthma). None of the participants reported a current mental disorder. At the beginning of the first semester, they performed a computerized dot-probe task, completed the short form of the BIS (BIS-15), and height and weight were measured for calculation of BMI (kg/m2) in the laboratory. In accordance with similar studies (e.g. Hodge et al., 1993), participants (N = 51, Mage = 20.4 years, SD = 4.03) returned at the start of the second semester (after approximately 6 months) for a follow-up measurement of body weight (mean period between the two measurements was M = 164 days, SD = 9.82).

Dot-probe task

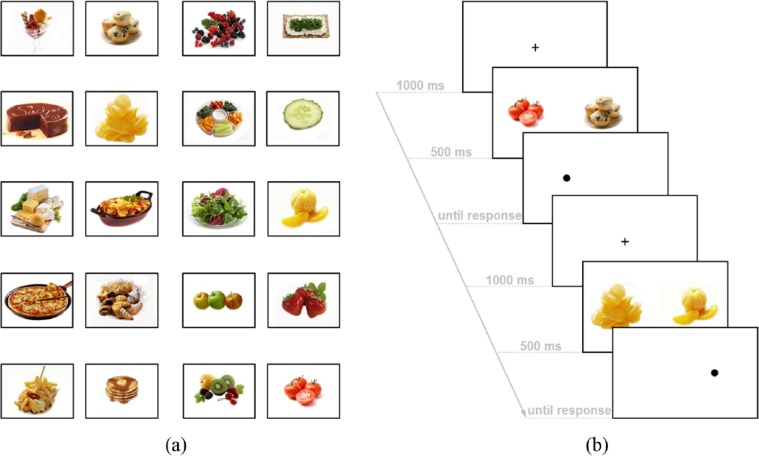

Twenty pictures were selected from the food.pics database (www.food-pics.sbg.ac.at), which contains information on calorie content, subjectively rated palatability, and physical features of the food pictures (Blechert et al., 2014). Ten pictures of HC (five pictures of savory foods, five pictures of sweet foods) and ten pictures of LC (five pictures of fruits, five pictures of vegetables/salad) foods were selected (Figure 1(a)).1 Food items of the two categories differed both in calories per 100 g (M = 321.15 kcal/100g (SD = 126.43, range: 123–539) vs M = 47.25 kcal/100g (SD = 40.05, range: 9–154), t(18) = 6.53, p < .001) and in calories displayed per image (M = 1769.62 kcal/image (SD = 1363.04, range: 183–4268) vs M = 102.23 kcal/image (SD = 128.89, range 1–415), t(18) = 3.85, p < .01). Picture categories did not differ in palatability, visual complexity, brightness, and contrast (all ts(18) < 1.84, ns).

Figure 1.

(a) Pictures of high- and low-calorie foods used in the dot-probe task. (b) Representative screen displays of the dot-probe task. Participants were required to respond with a left or right button press depending on the position of the dot.

Participants were informed that two pictures would appear on the screen, followed by a dot on one side of the screen. They were instructed to press a left button on the keyboard with their left index finger as fast as possible when the dot appeared on the left side of the screen and a right button on the keyboard with their right index finger as fast as possible when the dot appeared on the right side of the screen. Participants first performed a practice block of 15 trials containing non-food-related pictures (animals and flowers). In the test block, one HC and one LC image were displayed together in each trial (i.e. trials never consisted of two HC or two LC images at once). Picture pairs were presented for 500 ms (cf. Kemps et al., 2013, 2014). Trial procedure is displayed in Figure 1(b). Each image was presented four times (once on the left or right side with or without being followed by a dot). All possible picture pairs were presented resulting in 400 trials. Those were separated into two blocks to allow participants to rest after half of trials. The order of trials was randomized.

Impulsivity

The BIS-15 (Meule et al., 2011; Spinella, 2007) is a 15-item self-report measure of trait impulsivity and was chosen over the long version (Patton et al., 1995) because of its briefness and good psychometric properties (Meule et al., 2015). Three subscales, each consisting of five items, can be calculated representing attentional impulsivity (e.g. “I am restless at lectures or talks.”; α = .579), motor impulsivity (e.g. “I act on the spur of the moment.”; α = .641), and non-planning impulsivity (e.g. “I plan tasks carefully.” (inverted); α = .804). Internal consistencies were a little lower than in the validation study (α = .68−.82; Meule et al., 2011), but were comparable in that the non-planning impulsivity subscale had the highest internal consistency followed by the motor impulsivity and then the attentional impulsivity subscales. Descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of and correlations between study variables.

| N = 51 | M (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.8 (2.95) | – | |||||

| 2. Body mass index change (kg/m2) | 0.08 (0.89) | −.259 (p = .066) | – | ||||

| 3. Attentional bias score (ms) | −5.40 (10.6) | −.045 (p = .752) | −.117 (p = .415) | – | |||

| 4. Attentional impulsivity | 9.28 (2.08) | −.049 (p = .732) | −.116 (p = .417) | −.023 (p = .873) | – | ||

| 5. Motor impulsivity | 10.8 (2.31) | −.024 (p = .866) | .125 (p = .381) | .084 (p = .557) | −.042 (p = .772) | – | |

| 6. Non-planning impulsivity | 10.7 (3.09) | −.092 (p = .520) | −.021 (p = .884) | .357 (p = .010) | .131 (p = .361) | .488 (p < .001) | – |

Data analyses

In accordance with previous studies (e.g. Kemps et al., 2013, 2014), incorrect trials and trials with a reaction time of less than 150 ms and above 1500 ms in the dot-probe task were excluded from analyses and an attentional bias score was calculated by subtracting reaction times to dots replacing HC foods from reaction times to dots replacing LC foods. Thus, positive values indicate an attentional bias toward HC foods and negative values indicate an attentional bias toward LC foods.

Linear regression analyses were calculated with attentional bias scores, impulsivity scores, and an interaction attentional bias × impulsivity as predictor variables entered at once and with BMI change as dependent variable (Table 2). This was done for all three BIS-15 subscales separately. Variables were mean-centered before calculating the product term. Significant interactions were followed-up with simple slopes analysis at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) values of attentional bias score (cf. Aiken and West, 1991), indicating an attentional bias toward HC or LC food-cues, respectively. Attentional bias scores instead of impulsivity scores were used as moderator to parallel analyses by Nederkoorn et al. (2010), who used implicit food preference instead of response inhibition as moderator. As BMI was correlated with weight change in the study by Nederkoorn et al. (2010), BMI at the first measurement was entered as covariate in a second step. All regression analyses were computed using PROCESS for SPSS (Hayes, 2013).

Table 2.

Results of linear regression analyses for variables at the first measurement predicting change in body mass index.

| N = 51 | b | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 (R2 = .110) | |||

| Attentional bias | −0.01 | 0.01 | .606 |

| Motor impulsivity | 0.06 | 0.05 | .233 |

| Attentional bias × motor impulsivity | 0.01 | 0.01 | .049 |

| Step 2 (R2 = .180) | |||

| Attentional bias | −0.01 | 0.01 | .541 |

| Motor impulsivity | 0.06 | 0.05 | .233 |

| Attentional bias × motor impulsivity | 0.01 | 0.01 | .040 |

| Body mass index | −0.08 | 0.04 | .052 |

Results

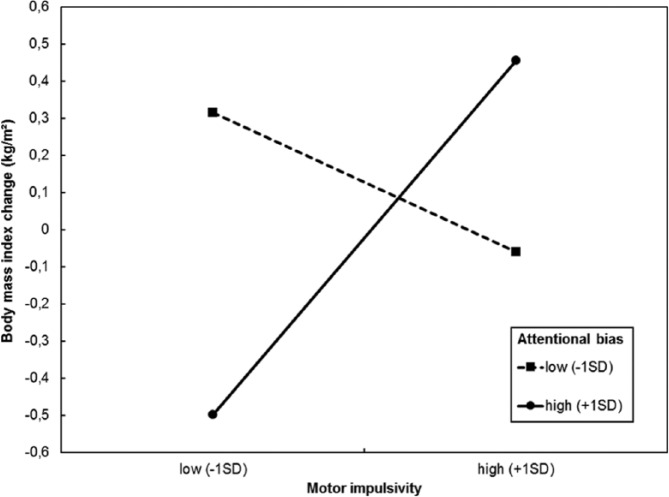

Excluded trials due to reaction time accounted for 0.19 percent of all trials. Incorrect trials accounted for 1.12 percent of all trials and did not differ between LC (M = 1.90, SD = 1.86) and HC trials (M = 2.49, SD = 3.15, t(56) = 1.45, p = .153). Correlations between study variables are displayed in Table 1. BMI at the first measurement was marginally significantly, negatively correlated with BMI change and non-planning impulsivity was significantly, positively correlated with attentional bias scores. The interaction term of attentional bias scores × motor impulsivity scores was a significant predictor of BMI change (Table 2). Predictors in similar models with attentional or non-planning impulsivity were not significant (all ps > .161). The interaction effect was still significant when including BMI as covariate (Table 2). Probing this interaction revealed that motor impulsivity scores were positively associated with weight gain in individuals with high attentional bias scores (b = 0.21, p = .027), but not in those with low attentional bias scores (b = −0.08, p = .318; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simple slopes probing the interaction of attentional bias × motor impulsivity when predicting body mass index change. Scores on motor impulsivity positively predicted weight gain in individuals with high attentional bias scores (i.e. those who exhibited an attentional bias toward high-calorie food-cues), but not in individuals with low attentional bias scores (i.e. those who exhibited an attentional bias toward low-calorie food-cues).

Discussion

The main aim of the current study was to investigate whether an attentional bias toward food-cues and impulsivity interactively predicted weight change in female students. Results showed that weight gain was indeed predicted by an interaction between attentional bias toward HC foods and self-reported impulsivity, but only its motor impulsivity subscale. This result is in line with and extends findings from previous studies, in which related, but distinct food- and impulsivity-related measures were used. In the study by Kakoschke et al. (2015a), for example, laboratory food intake was predicted by an interaction between approach bias for food and low motor response inhibition. Although a similar interaction effect using a measure of attentional bias instead of approach bias in that study fell short of significance, plotting the interaction revealed that it was descriptively similar to the finding obtained for approach bias and to the interaction effect obtained in the current study.

In the study by Nederkoorn et al. (2010), weight gain was prospectively predicted by an interaction between implicit preference for food and low motor response inhibition. In accordance with this finding, the predictive power of impulsivity for weight gain could only be observed for self-reported motor impulsivity, but not for attentional and non-planning impulsivity. Although results of studies using the BIS are fairly inconsistent, it appears that attentional and motor impulsivity in particular are related to overeating, while there is at most a minor role for non-planning impulsivity (Meule, 2013; Meule and Platte, 2015). In line with this, only attentional and motor impulsivity scores were positively correlated with attentional bias for food-cues in a study by Hou et al. (2011). Unexpectedly, however, only non-planning impulsivity was correlated with attentional bias scores in the current study. In a recent study, scores on non-planning impulsivity positively correlated with striatal brain activations during HC versus LC food choices (Van Der Laan et al., 2015). Thus, although non-planning impulsivity does not appear to be directly related to body mass, it may indeed be associated with a higher reactivity to HC food-cues (e.g. higher reward-related brain activation, biased attention allocation). Therefore, future studies are needed that address which facets of impulsivity are related to measures of overeating and to body weight, and examine possible moderators and mediators of these relationships in particular. Preliminary evidence, for example, suggests that the relationship between motor impulsivity and food intake may be mediated by levels of external eating (Kakoschke et al., 2015b).

It is important to note that there were no additive effects of attentional bias for HC foods and impulsivity when predicting weight change, but there was a crossover interaction. Yet again, the nature of this interaction closely parallels the one found by Nederkoorn et al. (2010). In their study, participants with strong implicit food preferences and effective response inhibition tended to lose weight over 1 year. Similarly, participants with attentional bias for HC foods and low motor impulsivity tended to lose weight in the current study. The authors speculated that this may represent an overcorrection effect, whereby “strong implicit preferences for tempting food cues may serve to remind people of the very self-regulatory goals they wish to attain [and] given sufficient self-regulatory capacity in the form of behavioral inhibition, people may actually attain their self-regulatory goals” (Nederkoorn et al., 2010, p. 392). This interpretation is also in line with the goal conflict model of eating behavior, which posits that successful restrained eaters (who have been found to score low on impulsivity; Van Koningsbruggen et al., 2013) have formed a facilitative link from palatable food stimuli to eating control and “even though palatable food stimuli also prime the eating enjoyment goal, the increased accessibility of the dieting goal helps them to inhibit eating enjoyment and to engage in healthy eating” (Stroebe et al., 2013, p. 125).

Interpretation of results is limited by the non-representative sample of young women who primarily had normal weight. Thus, future studies in other samples such as men and samples with a larger range in age and BMI are needed to confirm these relationships. Moreover, impulsivity was assessed by self-report, which is vulnerable to bias. However, previous studies have found that scores on the BIS are indeed related to response inhibition as measured by behavioral tasks, albeit correlations are rather small and inconsistent (Aichert et al., 2012; Lange and Eggert, 2015; Meule and Kübler, 2014; Meule et al., 2014). Finally, future studies need to address whether weight gain is really the result of increased intake of foods presented in laboratory paradigms (i.e. the foods that participants showed attention allocation to in the current study or showed an implicit preference for in other studies).

To conclude, the current study provides further evidence for the view that higher body weight is determined by an interaction between high automatic, motivational drive toward palatable food stimuli (in this case, automatic allocation of attention toward these stimuli) and low deliberative control capacity (in this case, high self-reported motor impulsivity).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carina Beck Teran, Jasmin Berker, Tilman Gründel, and Martina Mayerhofer for collecting the data.

Picture number in the food.pics database: 16, 26, 32, 40, 60, 82, 90, 106, 115, 143, 195, 201, 212, 217, 221, 224, 225, 234, 238, 275.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: AM is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (ERC-StG-2014 639445 NewEat, granted to Prof. Dr. Jens Blechert). Publication of this work was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Salzburg.

References

- Aichert DS, Wostmann NM, Costa A, et al. (2012) Associations between trait impulsivity and prepotent response inhibition. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 34: 1016–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. (1991) Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM. (2009) Neurobehavioral inhibition of reward-driven feeding: Implications for dieting and obesity. Obesity 17: 640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM, Woolf K, Pagoto SL, et al. (2011) Inhibiting food reward: Delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity 19: 2175–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blechert J, Meule A, Busch NA, et al. (2014) Food-pics: An image database for experimental research on eating and appetite. Frontiers in Psychology 5(617): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calitri R, Pothos EM, Tapper K, et al. (2010) Cognitive biases to healthy and unhealthy food words predict change in BMI. Obesity 18: 2282–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. (2008) The effect of an impulsive personality on overeating and obesity: Current state of affairs. Psychological Topics 17: 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. (2013) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Wagner DD. (2011) Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 15: 132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CN, Jackson LA, Sullivan LA. (1993) The “Freshman 15” facts and fantasies about weight gain in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 17: 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, Roefs A. (2009) Three ways to resist temptation: The independent contributions of executive attention, inhibitory control, and affect regulation to the impulse control of eating behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45: 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Holm-Denoma JM, Joiner TE, Jr, Vohs KD, et al. (2008) The “freshman fifteen” (the “freshman five” actually): Predictors and possible explanations. Health Psychology 27: S3–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou R, Mogg K, Bradley BP, et al. (2011) External eating, impulsivity and attentional bias to food cues. Appetite 56: 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakoschke N, Kemps E, Tiggemann M. (2015a) Combined effects of cognitive bias for food cues and poor inhibitory control on unhealthy food intake. Appetite 87: 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakoschke N, Kemps E, Tiggemann M. (2015b) External eating mediates the relationship between impulsivity and unhealthy food intake. Physiology & Behavior 147: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemps E, Tiggemann M. (2009) Attentional bias for craving-related (chocolate) food cues. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 17: 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemps E, Tiggemann M, Hollitt S. (2014) Biased attentional processing of food cues and modification in obese individuals. Health Psychology 33: 1391–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemps E, Tiggemann M, Orr J, et al. (2013) Attentional retraining can reduce chocolate consumption. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 20: 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange F, Eggert F. (2015) Mapping self-reported to behavioral impulsiveness: The role of task parameters. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 56: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence NS, Hinton EC, Parkinson JA, et al. (2012) Nucleus accumbens response to food cues predicts subsequent snack consumption in women and increased body mass index in those with reduced self-control. Neuroimage 63: 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A. (2013) Impulsivity and overeating: A closer look at the subscales of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Frontiers in Psychology 4(177): 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Kübler A. (2014) Double trouble: Trait food craving and impulsivity interactively predict food-cue affected behavioral inhibition. Appetite 79: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Lutz APC, Krawietz V, et al. (2014) Food-cue affected motor response inhibition and self-reported dieting success: A pictorial affective shifting task. Frontiers in Psychology 5(216): 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Mayerhofer M, Gründel T, et al. (2015) Half-year retest-reliability of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale–short form (BIS-15). SAGE Open 5(1): 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Platte P. (2015) Facets of impulsivity interactively predict body fat and binge eating in young women. Appetite 87: 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Vögele C, Kübler A. (2011) Psychometric evaluation of the German Barratt Impulsiveness Scale - Short Version (BIS-15). Diagnostica 57: 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, et al. (2001) Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry 158: 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Houben K, Hofmann W, et al. (2010) Control yourself or just eat what you like? Weight gain over a year is predicted by an interactive effect of response inhibition and implicit preference for snack foods. Health Psychology 29: 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. (1995) Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 51: 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert KRS, Po’e EK, Barkin SL. (2013) The relationship between executive function and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Journal of Obesity 2013(820956): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinella M. (2007) Normative data and a short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. International Journal of Neuroscience 117: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, et al. (2009) Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences 47: 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Van Koningsbruggen GM, Papies EK, et al. (2013) Why most dieters fail but some succeed: A goal conflict model of eating behavior. Psychological Review 120: 110–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Laan LN, Barendse ME, Viergever MA, et al. (2015) Subtypes of trait impulsivity differentially correlate with neural responses to food choices. Behavioural Brain Research 296: 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Koningsbruggen GM, Stroebe W, Aarts H. (2013) Successful restrained eating and trait impulsiveness. Appetite 60: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann J, Jansen A, Roefs A. (2015) Worry or craving? A selective review of evidence for food-related attention biases in obese individuals, eating-disorder patients, restrained eaters and healthy samples. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 74: 99–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokum S, Ng J, Stice E. (2011) Attentional bias to food images associated with elevated weight and future weight gain: An fMRI study. Obesity 19: 1775–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]