Abstract

Available evidence shows that an increasing number of soldiers are seeking help for post-traumatic stress disorder. The post-traumatic stress disorder condition has big emotional and psychological consequences for the individual, his/her family and the society. Little research has been done to explore the impact of nature-based therapy for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder although there is a growing amount of evidence pointing towards positive outcome. This qualitative study aims to achieve a deeper understanding of this relationship from the veteran’s perspective. Eight Danish veterans participated in a 10-week nature-based therapy. Qualitative interviews were conducted and analysed using the interpretative phenomenological method. The results indicated that the veterans have achieved tools to use in stressful situations and experienced an improvement in their post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Keywords: activities, interpretative phenomenological analysis, nature-based therapy, post-traumatic stress disorder, veterans

Background

Coming home from war to continue a non-active military life is challenging for many soldiers. For some, struggling with mental injuries becomes part of their daily lives. While physical wounds are most often visible, recognizable and treatable, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is invisible so to speak, and treatment seems to be more multifaceted due to the complex interactions between multiple biopsychosocial factors (Van der Kolk, 2000, 2001). Furthermore, individuals struggling with PTSD often also struggle with social problems, for example, substance abuse (David et al., 2004) and a higher level of general health problems (Jakupcak et al., 2010).

The increasing number of individuals developing PTSD calls for an active effort to identify and develop suitable evidence-based treatments. Common treatments offered to veterans today are, for example, medical and mental care. These treatments often last many years because they reduce symptoms; however, they do not cure the condition. For some individuals, these treatments make their daily life bearable and enable them to manage a job, whereas others only experience a minor effect of the treatment, or may even experience adverse effects that are perceived as worse than the positive effect of the treatments.

Nature has been used for health improvement purposes for centuries (Abraham et al., 2010; Marcus and Sachs, 2013). During World War I (WWI), a specific therapy, often referred to as horticultural therapy, was established and offered to soldiers who were traumatized during combat (Marcus and Sachs, 2013). The number of Western soldiers who suffered mental trauma during WWI and in subsequent wars facilitated the development of a horticultural therapy profession (Davis, 1998). The increasing amount of research on nature and human health relations confirms that nature can be a resource in relation to human health (Corazon et al., 2010; Dallimer et al., 2012; Keniger et al., 2013).

Today, a large variety of therapies use natural settings ranging from natural forests to specifically designed therapy gardens, as settings for the therapy. For example, wilderness therapy, ecotherapy and therapeutic horticulture have been used in projects for veterans suffering from PTSD (Poulsen et al., 2015). Although numerous non-scientific studies have presented positive results of using nature in therapy, the number of scientific studies in this area is still limited (Poulsen et al., 2015). However, the scientific studies that have been published indicate a positive impact of nature-based therapy (NBT) for veterans with PTSD (Dustin et al., 2011; Duvall and Kaplan, 2013; Krasny et al., 2014).

It could be assumed that NBT would have the same positive health effects on veterans with PTSD as it has been shown to have on individuals suffering from other mental diseases (Annerstedt and Währborg, 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2009). The veterans might have different reactions due to their military background, a long time pressure during war service and the circumstances in traumatization. Moreover, being a soldier also includes surviving and fighting in nature, the veterans have an existing relationship to, and specific knowledge of, nature. Therefore, there is a need for a closer understanding of the veterans’ own experiences of how nature and nature-based activities (NBAs) that are offered as part of a therapy programme may affect them.

The aim of this study is, through a phenomenological approach, to obtain a deeper understanding of the veterans’ experiences of both the nature setting and the NBAs offered in a 10-week nature-based treatment intervention.

In this study, NBT is based on Annerstedt and Währborg (2011) and Corazon et al. (2010) and defined as, ‘An intervention that initiates a therapeutic process aimed at recovery for a specific patient group where the NBT actively involves a specially designed or chosen nature setting’.

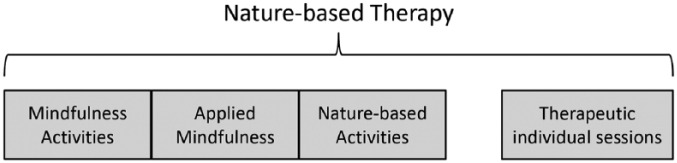

NBT contains of three elements: mindfulness activities and applied mindfulness, NBAs and individual therapeutic sessions. An overview of the content of NBT can be seen in Figure 1, and the activities are described more in detail in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Elements that are part of nature-based therapy.

Method

Study design

The study has a phenomenological approach and attempts to understand participant’s perceptions, perspectives and understandings of their life situation. The design of the study was inspired by the single case design (Yin, 2013). This case is defined as the participants (veterans with PTSD), the context is the forest therapy garden and the phenomenon is the participant’s experience of NBT. This particular article focuses on how a group of Danish veterans with PTSD experience nature, nature settings and NBA during and after a 10-week intervention with NBT in a forest therapy garden.

The participants

Potential participants were informed of the project through advertisements in daily newspapers and on websites for soldiers and veterans and through a co-operation with the Danish military rehabilitation unit. Veterans who had served abroad and were diagnosed with, or displayed symptoms similar to, PTSD could apply for participation. All information about the project was given orally and in writing.

Inclusion criteria were war veterans diagnosed with PTSD or with symptoms similar to PTSD. Exclusion criteria were psychotic conditions, abuse of alcohol or drugs, personality disorders or suicide risk.

Eight male veterans, aged 26–47 years, were included in the project. Participants had served in war zones between one and four times. Six of the participants had been diagnosed with PTSD. Onset of symptoms ranged between a few months and more than 3 years after homecoming. Seven of the included veterans received medical treatment for PTSD symptoms such as anxiety, anger and sleeplessness. Four of the participants self-medicated with marihuana. Three participants from the group worked part time at the military barracks. The remaining five were on sick leave.

One of the participants developed psychotic symptoms during the intervention and was therefore excluded from the study. One participant started an education 2 weeks before the NBT ended.

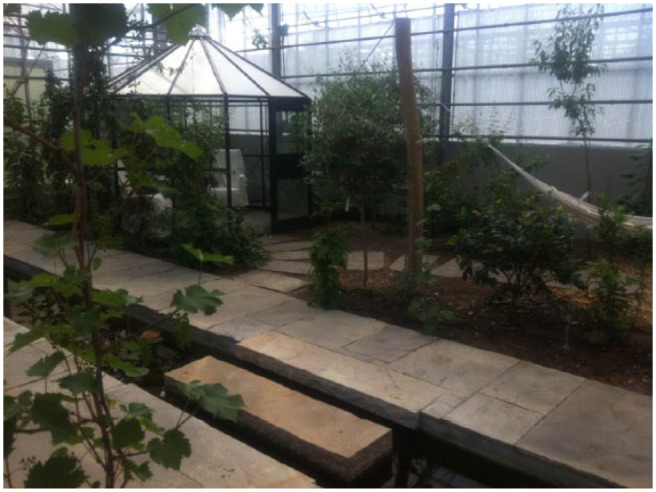

The nature settings

The NBT took place in the University of Copenhagen forest therapy garden Nacadia which is located in Hørsholm arboretum. The garden design is based on an exploratory model of an evidence-based health design (E-BHD) process (Stigsdotter, 2013). Both the specific therapy garden and the forest-like arboretum were used in the project. The arboretum covers an area of almost 40 ha (98 acres) and is open to the public until sunset. The forest therapy garden covers an area of 1.1 ha (2 acres) and includes tree buildings: a gardener’s cottage, a small wooden cabin and a 300 m2 greenhouse. In the greenhouse, there is an abundance of plants and climbers enclosing several sheltered places of relaxation with chaise lounges and hammocks.

Nacadia is characterized as a forest garden, with plant material that creates spaces with floors, walls and ceilings that enhance the feeling of being immersed in nature.

To arrive to the garden, the participants had to walk 600 m through the arboretum, a pergola covered with climbers guided the participants into the garden, and where the pergola ended, nature overtakes and encourages the participants to walk down the sloping terrain. The sound of bubbling water and a stream leaded the participants to the bonfire site. Some of the seating options were exposed, while others were hidden, for example, tree stumps hidden under dense tree branches and a platform in a larch tree, where the participants could be undisturbed.

The nature-based therapy

The NBT programme lasted 10 weeks, with 3 hours of therapy three times a week. The daily structure in the garden was designed to create a recognizable and secure framework for the participants. Each session started at the entrance to the arboretum, followed by a walk through the arboretum to the therapy garden. Mindfulness exercises in the therapy garden formed the basic introduction to the daily programme followed by NBAs. Next was the ‘private time’, where the participants chose themselves where they wanted to be and what they wanted to do in the nature settings. The programme started and ended with a gathering around a bonfire site in the therapy garden.

The NBT was based on the following three elements (illustrated in Figure 1): (1) mindfulness activities and applied mindfulness, (2) NBAs and (3) therapeutic individual sessions. The value of combining mindfulness activities, sensory experiences and NBAs is described by Corazon et al., (2010). Mindfulness and NBA were scheduled in every treatment and the individual therapeutic sessions (3) was conducted weekly.

The mindfulness activities (1) consisted of mindfulness activities based on Kabat-Zinn and Hanh (2009), and they included breathing techniques and dynamic yoga exercises (Kabat-Zinn and Hanh, 2009) aiming to lower the physiological effects of stress exposure and at re-establishing healthy flexibility in the nervous system. The exercises were conducted in the garden, but participants were also encouraged to make them part of everyday life in order to enhance the benefit for the participants. Applied mindfulness entailed to use the mindfulness approach when being in nature and doing NBA but also in a very concrete form where the veterans used the breathing techniques in stressed situations as sitting in a crowded bus. This part of the NBT had two objectives: enabling the veterans to be more perceptive to nature to utilize the calm created by the nature setting and second to give them tools to cope their everyday life.

The NBAs (2) contained different types of tasks; some with a particular physical approach, for example, wood splitting and planting trees, others were moderately physical demanding and involved performing routine tasks in the arboretum with the gardener. Through short narratives about, for example, special plants, birds breeding and seasonal changes in the forest, knowledge was imparted to the veterans. Activities initiated by the veterans were encouraged by the staff in order to support the participants’ self-motivation individual.

The therapeutic individual sessions (3) focused on guiding the veterans with regard to solving problems and conflicts in their daily lives through therapeutic talks. It was conducted when sitting in a sheltered place or during walks in the garden.

The therapists

A psychologist and a psychotherapist, who are both trained horticultural therapists, were responsible for the daily NBT programme. A gardener identified and initiated horticultural activities. Medical professionals with psychotherapeutic experience conducted weekly therapeutic individual sessions that were held in the therapy garden.

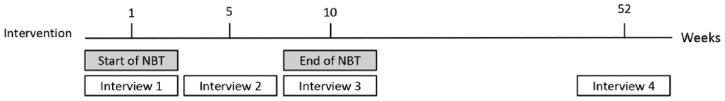

Data collection

The data material consisted of semi-structured individual interviews with eight Danish war veterans with symptoms similar to PTSD. Interview guides were created to explore the veterans’ experiences of the NBAs and nature. Four semi-structured, open-ended interviews were conducted with each participant: at baseline, after 5 weeks, after 10 weeks and 1 year after the treatment. This procedure is illustrated in the flowchart in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the study design.

Creating a pleasant and safe atmosphere during the interviews was considered important. In the first interview, this was achieved by letting the participants decide if the interview should be conducted in their home, in the military barrack or in the interviewer’s office. The second and third interviews were conducted in the intervention setting and the specific location was chosen by the participants. Finally, the fourth interview took place in the veterans’ homes or in the interviewer’s office. The interviews lasted between 46 and 94 minutes.

Data analyses

The process of the analysis was conducted stepwise in line with the procedure suggested by Smith and Osborne (2008) and Smith et al., (2009). It consisted of a repeated reading of the transcript interview and noting down sentences that seemed important for understanding what the participants were saying. This was followed by a reading process in which the other margin was used for noting down keywords and emerging themes that characterized the text. The themes identified were listed, and connections between them were found. Some subthemes were clustered and turned into superordinate themes with quotes from the participants supporting the meaning of the theme. In other cases, the subthemes shared the same central meaning (same superordinate theme), but their focus was on a different specific element.

This process was conducted for all interviews. Finally, a summery table of the superordinate themes was developed to get an overview of their interrelations to be used in the writing process. This is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

An overview of the superordinate themes and the corresponding subthemes.

| Superordinate themes | Subthemes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking nature in | Finding the places that feels right | Sensing the nature | Nature seems inclusive | |

| NBA as an initiator to a therapeutic process | Meaningfulness by doing things in and with nature | The therapeutic settings of NBA | Knowledge increases fascination about nature | Getting things done by oneself |

| Nature as a part of a life with PTSD | Transferability of features from the therapy garden to one’s own environment | |||

Parts of the interviews were analysed by one of the co-authors to capture possible inconsistencies in the interpretation and construction of the subordinate themes.

Ethical considerations

Prior to data collection, the study was granted ethical permission by The National Committee on Health Research Ethics. All participants were informed about the study both orally and verbally. They had the opportunity to participate in the treatment programme without participating in the study or to terminate participation at any point in time. All the veterans were anonymized in the written parts of the project. All participants signed written statement of informed consent. The pictures in this article only use models.

Results

The analysis of the interviews resulted in three superordinate themes: (1) taking nature in, (2) NBA as an initiator to a therapeutic process and (3) nature as a part of life with PTSD. The superordinate themes 1 and 2 comprised subthemes containing different aspect of the superordinate theme. Table 1 shows the superordinate themes and subthemes.

Taking nature in

This superordinate theme concerns the veterans’ experiences of being in the nature settings, of taking in nature so to speak. At the beginning of the therapy programme, they chose a specific location, however, after a few weeks; most of them chose a new location. Moreover, the participants slowly became more aware of the fact that the therapy garden and the surrounding arboretum provided nature experiences such as scents, weather conditions and wildlife. This led them to become more attentive to their bodily and mental reactions to being in the nature setting.

Finding the place that feels right

The veterans experienced the therapy garden as a comfortable place to be in, and they described how they felt that they were entering into another world when they were met with the quietness of the therapy garden. As part of the private time in the NBT, they identified locations in the therapy garden or in the arboretum that felt right to them at that moment. They described how they searched for specific qualities in the locations using words such as ‘having special value’, ‘being on its own terms’ or ‘placing no demands’.

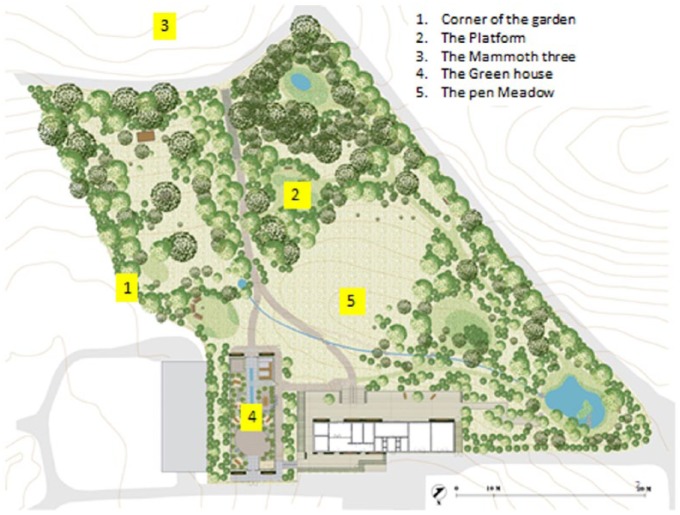

In the beginning of the therapy, all the veterans preferred locations in Nacadia where they were far away from public paths. One of the participants described his chosen location in a remote corner of the garden (Picture 1) where he could sit with his back against a bank of earth as a place where he could find comfort (the numbers in the text refers to the locations in the garden that can be seen in Figure 3 and to the pictures of the locations):

Here, I can sit shielded from people looking into the garden. I can see the field, and I have … a kind of backing here.

Picture 1.

Earth in the corner of the garden that provided shelter for a participant.

Figure 3.

A map showing Nacadia where the numbers refer to the locations mentioned in the text.

Another participant enjoyed sitting on the platform placed up in one of the trees in the therapy garden, as he could see the entire area from there (Picture 2).

Picture 2.

Platform and the view of the garden and forest.

Others chose a very characteristic tree in the garden, the mammoth tree (Picture 3) with branches that spread down to the ground, as they felt sheltered there. One veteran stuck to the gardener’s greenhouse (Picture 4) for the first weeks of his participation. He experienced a parallel to his sunroom at home, the room in which he spent most of his time when at home. He felt safe in the gardener’s greenhouse where he was surrounded by green plants.

Picture 3.

Participants felt sheltered when sitting below the branches of the huge tree.

Picture 4.

Several places for restoration could be found in the greenhouse.

Using nature as a safe place was important with regard to lowering the participants’ feeling of alertness. One veteran reported how he felt that the nature settings provided so much protection that he even could close his eyes, something that he rarely felt he could do in public. Others found that being in specific locations in the nature settings had positive impacts on their PTSD symptoms. In the words of one of the veterans,

Sometimes, when I have too many things to think about, I have this inner dialog with myself and my brain works far too hard … then, being here, it doesn’t stop totally, but, it feels like a part of my head is more relaxed.

The participants’ preferences with regard to nature qualities changed during the intervention period. After a few weeks, most of the veterans began testing different locations with other qualities. The new locations they chose were less sheltered, for example, the open meadow (Picture 5) with its scattered planting of grass and shrubs and flowers. Some of the veterans found the new locations themselves, whereas others returned to locations they had visited together with the gardener.

Picture 5.

Open meadow invited the participants to sit or lay in the grass.

During the private time part of the therapy programme, the veterans preferred being alone at the beginning of the NBT, but later some of the veterans chose the bonfire as the location they felt most comfortable in. They expressed how their need for being alone had changed and the preferred location with other peoples’ presence, especially other veterans, was important. One veteran chose a bench outside the therapy garden, in the arboretum. It was surrounded by some small trees and had a view of the lake. He highlighted this location as containing the wilderness of nature (e.g. some dead trees leaning out in the water) that he experienced as more valuable than the smaller lake in the therapy garden which he described as ‘arranged nature’.

The veterans seemed to seek a connection between the characteristics of the nature setting in the location of their choice and their mental state. As is seen in the following quote by one of the participants, they were very conscious of the different demands of the different locations and sought out ‘mental matches’ in the therapy garden or in the arboretum:

This is such a being-alone-place [sitting in the shadows of high fir trees]. In times when the energy is low and it is hard to be with other people, this is the place.

This reflection might be an indication of an intuitive process that arose from the participant’s bodily experiences of his own mental state when finding the location that felt right for him at that specific time.

Sensing nature

The veterans experiences how being in the therapy garden led to an attention both on themselves and on nature. They emphasized that the sensory experiences were the scents of the plants and the soil, changes in the sunlight when clouds drifted in front of the sun and the coolness in the shadows from the tall trees were experienced as having a direct bodily impact. The participants’ attention to nature increased over time, as well as the importance of what they sensed. Depending on what their favourite location was, they discovered different things, for example how the leaves moved in the wind, the ripples on the lake’s surface and the sound of birds singing from different places in the arboretum. One veteran talked about the big mammoth tree,

I think this is the biggest tree here. When you touch it, it’s almost porous, and feels snug. It has such a thick bark to protect itself. It gives me peace here; it has quite a majestic feel about it, such an old tree.

The participants also emphasized the effects of seasonal and diurnal variations. For example, outside the garden, the participants experienced that the darkness of the afternoons offered sheltered as they could walk unseen in the semi-dark. Some of the veterans pointed out how rain had a special purifying effect on them, and listening to the sound of the raindrops had a soothing effect. Furthermore, the rain also kept other people inside which made it more attractive to go out.

Nature seems inclusive

The unchangeable and enduring character of nature was experienced as calming, and the veterans perceived the old trees with their thick trunks as an expression of stableness that they physically could lean against. They mentioned how the unchangeability of nature at the same time also contained slow variations over time; the changing colour of the leaves; and the rise and fall of the water level in the stream. These experiences were expressed by all the veterans. One veteran described it in the following way:

The plants and the trees, they don’t change at all. But then again, in two days’ time, they won’t look quite the same. And they move, no big movements, but … a predictable rhythm to follow. And trust. And your brain doesn’t have to use energy to analyse it.

Another veteran highlighted the fact that nature made no demands:

[Nature is special] because there are no demands and expectations to you. Well, there is a tree, and I am sitting here, no expectations, no questions, no nothing.

The way in which the veterans experienced nature as a place where you are accepted just the way you are, and their experience of the brain being relaxed, seemed to be important for the healing process. When compared to the veterans’ descriptions of the turmoil, they felt when they were in the city with its bright colours, fast moving cars and loud and shrill sounds, the garden and the arboretum seemed to provide the veterans with a place of recovery.

Moreover, the veterans felt that nature provided experiences that were fascinating; however, if they were to grasp these situations they had to really pay attention to nature:

If a deer comes by, then it’s now! You see, it won’t happen again, so if you want to enjoy it, then you must have your attention focused on the right here, right now. That’s actually a good thing to remember, when your thoughts are racing.

This participant was fascinated by nature, and he knew that this kind of thing only happens when you are present in the moment. All the veterans eventually discovered what nature could provide of fascinating experiences when they were able to seize the now. For the veterans suffering from symptoms such as turmoil and anxiety, having felt on their own bodies that the NBT could lower their stress levels in a way that allowed them to feel calm inside, and thereby be aware of different aspects of their lives was an important experience.

NBA as an initiator to a therapeutic process

The NBAs were created so as to match the conditions of the veterans taking into account their different levels of mental and physical energy, their ability to concentrate and manage a task, and their preparedness to work with others. The veterans expressed how they experienced the NBA as having an impact on their condition in several ways.

Meaningfulness by doing things in and with nature

In the beginning of the therapy, most of the veterans needed to rest a lot, but gradually they felt more capable of participating in other activities. For some, it was a challenge to sit quietly because of an inner turmoil. Different degrees of mentally and physically demands in the NBA, the numerous ways of ‘being and doing’ in nature and the adjustment to the veterans’ competences were described as an important part of the NBT. The activities were described by the participants as being meaningful in themselves although they had their individual approaches; weeding and chopping firewood reminded one veteran about his inability to deal with these kinds of activities at home, and as a consequence he chose activities that were related to a more wild type of nature. In contrast, another veteran experienced precisely these everyday activities as almost being meditational for him:

It is kind of zen-like … you have to be focused to get the precision in the chop and find the exact force in the motion. You watch the two pieces of wood fall to the ground, and place a new piece of wood on the chopping block.

The participants described being engaged in a NBA as a release due to the absence of disturbing thoughts that often occupied their minds:

I feel most comfortable when I’m doing something, like now, we are building some bird boxes that actually will be hung up around here. I like that. My thoughts are more focused. But I also like doing the yoga and mindfulness exercises. Really, I have enjoyed them as well, because I can begin finding peace in my own body.

When describing the bird-box-building activity, the veteran explained that, for him, there were two layers in the activity; first, hanging up the bird box gave him satisfaction because of the usefulness of the activity, and second, giving something back to nature provided him with a feeling of coherence with nature because he was giving the birds a nesting place.

The therapeutic settings of NBA

All the veterans emphasized the importance of the staff’s attitude to their condition with regard to their motivation to participate in the NBA. As almost all the participants had a latent fear of their symptoms escalating, they felt great relief that the staff did not put pressure on them. In other treatment programmes, some of the veterans had not felt safe and secure and has avoided specific activities that included, for example, talking about their memories, because they feared this would worsen their condition. However, in the NBA offered here, they felt respected; they were encouraged to listen to their own needs and respond to these needs, thereby guiding them to take care of themselves:

We are really obliged to DO something in particular … for example, the bird boxes we are working on. It’s our own decision whether we finish them or not. But we really want to. But then again, if we need to rest instead, it’s totally okay here.

The participants reported that pedagogical approach was a motivator for them, and they began to help organize the activities by performing practical tasks such as finding materials, lighting the fire and so on. Moreover, the NBT appeared to provide the participants with feelings of success when they succeeded at finding a balance between their own conditions and the specific activity they chose. This seemed to improve their focus and motivation to work with their personal abilities and difficulties.

The individual therapeutic sessions were conducted in the therapy garden. The veterans were positive about this change of setting; during other programmes, therapeutic sessions normally took place in the psychotherapist office. Being or walking in nature made them feel better and the veterans often chose to walk during the sessions because of their inner turmoil. Sometimes, the sessions took place in the wooden cabin or under a tree.

On one occasion, an activity evolved in another direction than originally planned. Several of the veterans featured this episode as an important one: the group walked slowly through the arboretum, walking in their own thoughts. Then the veterans, without thinking about it, automatically followed their instincts as soldiers and formed their positions as if they were going on patrol. In their minds, the walking and the forest environment were associated with being in combat. The participants described how they experienced alertness and a feeling of fear and arousal in their bodies. For both the participants and the staff, this experience revealed how deeply they were marked by their time serving in a combat zone.

Knowledge increases fascination about nature

Most of the veterans enjoyed being able walking in the arboretum with the gardener to inspect trees and plants. The gardener’s short narrations about the plants and animals in Nacadia and the Arboretum captured the veterans’ attentions, and this new knowledge motivated them to participate in the NBA. Nature was known to the participants in the way, they could survive in it, but in these new settings, knowledge about nature was presented in a different way and with a different purpose. In a way, their relationship with nature expanded in a positive way through the NBA:

Nature has always meant a lot to me. The activities we do up here … it’s like basic things. We found a tree out here, and tasted the leaves, – it’s a ginkgo. I had to find out where I can get a tree like that; you can use the leaves in a salad. Things like that … give me a lot.

Getting things done by oneself

The veterans experienced being in the garden and participating in the NBA as calming and meaningful. This experience could be interpreted as the first step towards changing their lives outside the therapy garden. During the 10-week intervention, the participants changed the way in which they talked about living with PTSD. In spite of these positive changes, it was challenging for some of the participants to continue the intervention activities when they were at home, for example, the mindfulness exercises, yoga, spending time in nature or being active in nature environments:

For me, it is like this; when I put my feet on the ground up here, it’s like leaving everything behind. I’m just here, and we do the yoga, the activities and so. And it is fantastic … but at home … I simply can’t do these things on my own.

This can be understood as the participant’s own garden at home might be too demanding with its visible demands of maintenance compared with Nacadia where no demands were made regarding garden-related maintenance. Taking the initiative to practice the NBA at home might also be too challenging. Furthermore, the activities conducted in the garden could be understood as being linked to a specific context, namely the therapy garden, while the private home provides other kinds of activities related to the household. His lack of concentration and at his frustration regarding a decreased capacity to the same things that he did before his PTSD might also be a way to understand this quotation. Another veteran described it in the following manner:

Also, if I start doing something [at home], and someone comes and says ‘What’s that?’, I lose interest immediately and throw out the shit and leave the place. I can’t keep my focus for a long time, and nothing can annoy me.

All the veterans became better at using breathing deeply in stressful situations and maintaining their focus during the mindfulness exercises. These tools acquired during the NBT helped them overcome anxiety in situations where there were many people, for example, in buses and shopping centres. Some of the veterans expressed an increasing readiness for participating in activities to resume some of the hobbies they had enjoyed before the PTSD, for example, repairing a bike.

Also, the fascination of nature seemed transferable:

Where I live, there is a churchyard nearby, so we have a lot of tall trees, and I have noticed that I actually stand thee looking at the trees without thinking about anything at all.

Nature as part of a life with PTSD

Participating in the NBT made an impression on the veterans in many ways, as described above. The aim of the NBT was to improve the conditions of the veterans, both while they were in the garden and in everyday situations as well. The veterans were interviewed 1 year after the therapy had ended, and in general, it was found that nature still played an important role and was highlighted in very different ways. Some of the participants reported very concrete episodes while others described their experiences at a more metaphorical level. One participant described a need for being active and using the nature because he had experienced how it had a positive impact on his inner turmoil:

I have to do something where I don’t have to think a lot … I have been at my mother’s house to cut down some trees. I can feel something good happens to me … It’s just more fun when you have cut down the tree yourself [he laughs]. It’s me who has cut down this little piece of wood.

The satisfaction of having planned and carried out the task, and the feeling of success when the task was completed, was important to him.

Another veteran had his arm tattooed. The tattoo was both a symbol of process he had been through and a reminder of the importance of continuing the ‘inner process’ (NBA) he had started in the therapy garden. The veteran who had said that the activities involving chopping wood reminded him of his inability to get this kind of task done at home had taken this realization to heart and had sold his house with the garden he could not keep tidy. He had now moved to a little cottage in the middle of a forest where he could find the peace he searched for. He said about finding the cottage:

When the house was sold, I had to find something to live in, but I hadn’t imagined this – because, it is not something you just find! And when I saw it, I said: Yes (damn), this is it … And the other night when I was standing outside looking up at the stars, I just felt so relaxed, so relaxed.

Transferability of experiences from the therapy garden to participants’ own home environment

The ability to use the positive experiences from the garden and transfer it to the veterans daily living seemed essential in order to avoid that the treatment effect decreases at end of treatment. During the intervention, one said,

For me, it is like this; when I put my feet on the ground up here, it’s like leaving everything behind. I’m just here, and we do the yoga, the activities and so. And it is fantastic … but at home … I can’t make me do it by myself.

At that time, it seemed to demanding for him, to do the activities (here = mindfulness activities which also included yoga exercises) on one’s own. Although, after 1 year, it might appear as all the veterans have found a way to use part of the therapy in their daily living. Another veteran said,

I found someone to do those things in nature with. We are 4-5 veterans, and we stay in nature for 2-3 days. The breathing … to breath, and feel the ground under my feets. I I become more conscious of it when I am in nature.

The same veteran reflected over, how, when he was in nature, felt the strength to find shelter for the night, gather firewood and keep the fire burning. He was able to cook a dinner and sit relaxed by the fire. At home, he still sometimes found it difficult to get out of bed in the morning. This could be seen as nature provides a setting with low demands, where basic tasks such as keeping warm and cooking a meal seem simple or manageable compared with the more complex tasks of the civilian world. However, it could also simply be that the skills he had acquired as a soldier were deeply ingrained.

For others, nature became part of their daily living as a place for restoring; they sought out nature regularly when they needed to find peace, or when they needed to solve a problem.

Despite these positive examples, for some of the participants, PTSD symptoms such as anxiety and turmoil were still so invalidating that leaving their homes was impossible in periods. However, they still had dreams of a positive future to have a small house, to grow vegetables and enjoy being in nature.

Discussion

This analysis has resulted in three superordinate themes: (1) taking nature in; (2) NBA as an initiator to a therapeutic process and (3) nature as a part of life with PTSD. In the following, these three themes will be discussed against relevant theories and research in the field.

The first theme, taking in nature, focused on the veterans’ experiences of nature during the NBT. The two nature environments to which the participants were exposed were experienced as comfortable, as having special values, and being on its own terms. The participants described how they were able to find locations that had specific nature qualities that felt right to them at that precise moment. The veterans’ relation to the nature settings can be analysed using attention restoration theory (ART). In accordance with this theory, the human mind has two types of attention: directed attention and spontaneous attention (Kaplan, 1995). Directed attention is activated when the individual needs to concentrate and focus on a specific stimulus, and it sorts and selects the stimuli on which the individual needs to focus. This process is mainly intentional and requires a conscious effort. With prolonged use, the directed attention may be depleted, which may cause directed attention fatigue (Kaplan, 2001; Kaplan et al., 1998). Bearing this in mind, the veterans’ feeling of low mental and physical energy could be seen as a consequence of their constant alertness and can in fact be compared with the ‘directed attention fatigue’ condition described by Kaplan et al. (1998) although this connection has not yet been described in the literature. Taking nature in might be a way for the veterans to restore their nerve system and thereby their symptoms of PTSD.

One way to recover from directed attentional fatigue is to visit environments where one can rely solely on spontaneous attention, which is involuntary and non-effortful. When spontaneous attention is activated, the demands on the individual’s directed attention are reduced. Spontaneous attention is activated in so-called restorative environments, where the amount of stimuli is manageable and adequate. Restorative environments require four conceptual components (Kaplan, 1995): being away (the individual is physically or psychologically distant from everyday routines and demands), fascination (fascination that effortlessly hold the individual’s attention and triggers processes of exploration), extent (the capacity to provide scope and coherence that allow the individual to remain engaged) and compatibility (the match between what the individual wants to do and what the environment supports). Those elements might be found by the veterans, for example, when finding a place to sit on their own, watching a deer passing by as described in superordinate theme 1. Also the feeling of calmness when entering the garden and the veteran’s fascination of special plants in the garden can be related to the ART theory. Herzog et al. (1997) suggest that nature environments activate spontaneous attention and often offer the four restorative components. According to Hartig et al. (2007), the term ‘restoration’ refers to ‘the process of renewing physical, psychological and social capabilities diminished in ongoing efforts to meet adaptive demands’. The examples of the participants’ experiences of nature as having no demands support the environments compatibility in relation to the veteran’s needs (indicates that they experienced the nature settings as restorative).

In addition to the restorative quality of nature, participants also stressed the importance of the quality of ‘feeling security’ in nature (Superordinate theme 1). Specifically, environments that accommodated the participants’ need for shelter were preferred, and they used a bank of earth and branches to fulfil this need for shelter from the surrounding world. A parallel can be drawn to Korpela et al. (2001) on relations between favourite places and the restorative experience that addresses the need for being alone without disturbing others, while it keeps the attention to nature. Here, favourite places offer a ‘window into the use of environments for self and emotion regulation’ (Korpela et al., 2001: 576) as well as the need. The prospect-refuge theory (Appleton, 1975) can also be brought in here to further support this finding. According to Appleton, the ‘prospect’ provides an overview of the landscape, while ‘refuge’ represents a safe and secure place to hide. This need for security is also seen in similar target groups, for example, Van der Kolk (2002) describes how traumatized people often rely on the protection from others or to be in places that they experience as safe.

In general, the veterans described how low levels of mental and physical energy made it hard for them to get things done find suitable places in their everyday living environment. However, when they were in their preferred locations as part of the NBT, nature was experienced as having low or no demands. This experience can interpreted as low activation of their directed attention; the nature settings drew the participants’ attention to the environment in an effortless way that is also described in the introspective research by Ottosson (1997).

During the course of the therapy programme, the veterans’ preferences for locations changed from wanting to be alone and in location that offered shelter at the beginning, to seeking out new locations where they were together with other veterans or people in general in public spaces. It would be reasonable to see this change as a development in the veterans’ mental and physical capacity. Several theoretical approaches are found to illuminate this presumption. According to Searles (1960), humans who are affected by mental illness or grief need stable environments and relationships that place little or no demands on them. Stones place no demands, plants demand more, animals even more, but at the same time, they also respond to the individual, and may even give something back. Being together with other people is seen as the most demanding relationship. Being in a context that enables one to create successful relationships can, according to Searles (1960) and Ottosson (2001), increase self-confidence and well-being. This seems to describe the veterans’ need for finding places that ‘feel right’. The supportive environment theory (SET) developed by Stigsdotter and Grahn (2002) further develops this thinking. SET discusses the relationship between the individual’s mental strength (capacity to perform executive functions) and the need for supportive environments. It can be illustrated with the aid of a four-tier pyramid: at the bottom of the pyramid, the mental capacity is very weak, and the need for environments with only few demands is big. Gradually moving towards the top of the pyramid, mental capacity increases, the need for environments with low demands decreases and the capacity to handle more complex relationships with others increases (Stigsdotter and Grahn, 2002; Grahn and Stigsdotter, 2010). In this study, differences in the veterans’ pace of improvement with regard to their conditions and their preferences of locations were reported. Moreover, several fluctuations in their conditions during the NBT were stated. Since the veterans reported using more demanding locations and seeking out more contact with others as time passed by, it can be argued that they were at the lower levels of the SET pyramid at the beginning of the NBT, and over time they gradually moved towards the top. This could also be seen in the veteran’s daily routines in that they were able to participate in more activities with others, such as family and friends.

The NBA as a facilitator in a life-changing process

In general, the veterans felt that the NBA was motivational and meaningful. They highlighted the importance of the different activities that had different demands with regard to activity level, ranging from, for example, laying in a hammock, to fishing or wood splitting. Looking at NBA through an occupation perspective, theories of occupation therapy can be used to discuss these findings. According to Kielhofner (2002), occupation can be seen as a dynamic relationship between an individual, the environment and occupational activities and it seeks to understand people with their social, cognitive, physical and emotional ‘impairments’. The model of human occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner, 2002) suggests that an individual consists of three inter-related components: volition, habituation and performance capacity and the model explain how people select, organize and begin activities. Although the NBA was not created with the MOHO model as its theoretical framework, it may add a broader understanding of the interaction between the NBA, the participants and the nature settings. When the veterans describe the NBA as meaningful and motivating, it seems likely to assume that the level and type of activities were adjusted adequately to suite the participants’ needs. In order to be motivated to perform an activity, according to Kielhofner et al. (2001) and Persson et al. (2001), a feeling of attraction based on the anticipation of a positive experience is required. This can be related to the flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) which is part of the theoretical frame for the MOHO model. The need for an individual approach in the NBA was seen in the wood chopping activity; whereas the activity stressed one participant, it led another to a meditative state, which could be seen as an example of ‘flow’ defined as the ultimate enjoyment of a task, at state that occurs when a person’s capacities are optimally challenged (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Kielhofner (2002) also argues that participating in activities with others internalizes one’s identity and is a way of behaving and belonging to a role. The group of participants had roots in the same military culture, and the soldier’s role entails obeying orders and performing optimally. The NBA can be in contrast to this due to its focus on following one’s own needs (and activities) as part of the treatment. According to Kielhofner, this individualized approach might contribute to a life-changing process and a change of one’s identity (Kielhofner, 2002).

The range of activities combined with the accepting approach from the staff was emphasized by the participants as a positive experience. They felt they were seen as individuals and that their own perception and assessment of their condition was acknowledged by the staff. The participants described how everyday duties were challenging and how this caused frustration in their daily lives and underpinned the feeling not being able to do the same things as before the PTSD. Experiencing a feeling of success through the NBA was perceived as conducive for working with their personal challenges in life. Bandura (1997) defines self-efficacy as one’s belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations. The concept is part of the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), and numerous meta-analyses verify the generality of ‘efficacy beliefs’ as a significant contribution to the quality of human functioning. Benight and Bandura (2004) describe the role of perceived self-efficacy with regard to post-traumatic recovery, and a number of studies deal with soldiers. Solomon and Mikulincer (2006), Ginzburg et al. (2003) and Blackburn and Owens (2015) found that a higher general self-efficacy was associated with lower PTSD severity. This indicates that focusing on strengthening self-efficacy supports the treatment of combat trauma (Blackburn et al., 2015). The veterans in this study were not specifically asked about self-efficacy in the interviews, but it can be argued that the information from the interviews indicate that the NBA increased their belief in their own capacity and improved their thinking about themselves and their situation. This new and improved self-perception may be the result of the veterans’ improved understanding of their own bodily signals. Altogether, it can be argued that this has led to increased self-efficacy.

Nature as a part of a life with PTSD

Increased self-efficacy could be seen as part of the foundation for the courage and initiative the participants described, and after a few weeks, they felt more responsible with regard to initiating activities in Nacadia. Moreover, the participants seemed to be able to draw on this increased self-efficacy in their life outside the garden.

Knowledge about nature, by narratives from the gardener during walks in the arboretum, seemed to develop the veterans’ fascination for nature. Although the NBA was not designed to involve learning situations, the participants expressed that they enjoyed acquiring applicable knowledge about, for example, edible plants. A number of other studies, for example Atkinson (2009), focus on acquiring skills within horticulture with the aim of contributing to the veterans gaining a new profession. Whether the participants in this study have gained such skills cannot be said.

The participants were encouraged to perform NBA on a daily basis, for example, applied mindfulness by walking slowly in nature. However, they were ambivalent with regard to performing these activities on their own; on the one hand, they felt a need to practice parts of the NBA or visit nature areas close to their homes, and on the other hand it was challenging for them to do so on their own. This indicates a small gap between the staff’s expectations and the participants’ conditions and some might have a need for guided support. Another reason why the participants found it challenging to transfer the NBA to their everyday lives outside of the garden could be that they perceived that the NBA as being tied to the specific nature settings in the garden and to the staff. When the NBT ended, there were no therapy gardens, no NBT, NBA or staff available for the veterans. This underlines the importance of being able to perform some of the NBA on your own. One year after the intervention, the veterans in general used nature for slightly different purposes than before the treatment, and several of them focused on physical and mental restoration. This indicates that the veterans found their own way in using nature in a restorative perspective.

Limitations of the study

The limitation of the study is mainly the small numbers of participants. However, in spite of the small number of participants, the variation in the participant’s ages, differences in the length of employment in the military and differences in the length of time suffering from PTSD symptoms might indicate that the participants represented many perspectives on the experiences of nature and NBT. Therefore, it can be assumed that results from this study may be applicable in the planning of treatment programmes for veterans with PTSD.

Conclusion

This study found that, during and after the NBT, veterans with PTSD experienced the therapy garden Nacadia and in part also the surrounding forest-like arboretum as a place in which they felt included and as place of no or low demands. Their preferences with regard to the characteristics of important locations in the therapy garden changed during the intervention; they went from preferring locations that offered refuge and were considered safe, to preferring more open areas and locations where they could welcome the company of other veterans, or even the more public locations in the arboretum. The veterans experienced that their conditions and needs due to their PTSD could be remedied by simply being in the garden, and by performing the NBA. The NBT seemed to enable the veterans to find their own way in transferring the use of the nature and NBA to their everyday living. It was experienced as challenging to initiate and continue using nature without the guidance of the staff, but the veterans seemed to find their individual solutions to this challenge. One year after the NBT had ended, most of the veterans were still using nature and NBA. However, for one of the veterans who suffered from a high level of anxiety, it was not possible to continue the use of nature; nevertheless, it was still an aim and a dream for him to do so.

This study generated a deeper insight and understanding into how the veterans in this study experienced the nature settings and the NBA. This knowledge contributes to the understanding of the relationships between nature settings, NBA and the supportive approach from the staff.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abraham A, Sommerhalder K, Abel T. (2010) Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. International Journal of Public Health 55(1): 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annerstedt M, Währborg P. (2011) Nature-assisted therapy: Systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 39(4): 371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton J. (1975) The Experience of Landscape. London: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson J. (2009) An Evaluation of the Gardening Leave Project for Ex-military Personnel with PTSD and Other Combat Related Mental Health Problems. Glasgow: The Pears Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Bandura A. (2004) Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy 42(10): 1129–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn L, Owens GP. (2015) The effect of self efficacy and meaning in life on posttraumatic stress disorder and depression severity among veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology 71(3): 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazon SS, Stigsdotter UK, Jensen AGC, et al. (2010) Development of the nature-based therapy concept for patients with stress-related illness at the Danish healing forest garden Nacadia. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture 20: 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper Perennial, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dallimer M, Irvine KN, Skinner AM, et al. (2012) Biodiversity and the feel-good factor: Understanding associations between self-reported human well-being and species richness. Bioscience 62(1): 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- David D, Woodward C, Esquenazi J, et al. (2004) Comparison of comorbid physical illnesses among veterans with PTSD and veterans with alcohol dependence. Psychiatric Services 55: 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S. (1998) Development of the profession of horticultural therapy. In: Simson S, Straus MC. (eds) Horticulture as Therapy: Principles and Practice. New York: Food Products Press, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dustin D, Bricker N, Arave J, et al. (2011) The promise of river running as a therapeutic medium for veterans coping with post-traumatic stress disorder. Therapeutic Recreation Journal 45(4): 326. [Google Scholar]

- Duvall J, Kaplan R. (2013) Exploring the Benefits of Outdoor Experiences on Veterans. Ann Arbor: Available at: https://content.sierraclub.org/outings/sites/content.sierraclub.org.outings/files/sierra_report_6_13_exploring%20the%20benefits%20of%20outdoor%20expereinces%20on%20veterans%20(1).pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, Dekel R, et al. (2003) Battlefield functioning and chronic PTSD: Associations with perceived self efficacy and causal attribution. Personality and Individual Differences 34(3): 463–476. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez MT, Hartig T, Patil GG, et al. (2009) Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: A prospective study. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 23(4): 312–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn P, Stigsdotter UK. (2010) The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landscape and Urban Planning 94(3): 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig T, Kaiser FG, Strumse E. (2007) Psychological restoration in nature as a source of motivation for ecological behaviour. Environmental Conservation 34(4): 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog TR, Black AM, Fountaine KA, et al. (1997) Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 17(2): 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, et al. (2010) PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors 35(9): 840–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN. (2009) Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York: Delta. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R, Kaplan S, Ryan R. (1998) With People in Mind: Design and Management of Everyday Nature. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. (1995) The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 15(3): 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. (2001) Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior 33(4): 480–506. [Google Scholar]

- Keniger LE, Gaston KJ, Irvine KN, et al. (2013) What are the benefits of interacting with nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10(3): 913–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielhofner G. (2002) A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Kielhofner G, Mallinson T, Forsyth K, et al. (2001) Psychometric properties of the second version of the Occupational Performance History Interview (OPHI-II). American Journal of Occupational Therapy 55(3): 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpela KM, Hartig T, Kaiser FG, et al. (2001) Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places. Environment and Behavior 33(4): 572–589. [Google Scholar]

- Krasny ME, Pace KH, Tidball KG, et al. (2014) Nature engagement to foster resilience in military communities. In: Tidball KG, Krasny ME. (eds) Greening in the Red Zone. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus CC, Sachs NA. (2013) Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson J. (1997) Naturens betydelse i en livskris (Stad & Land 148). Alnarp: Movium. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson J. (2001) The importance of nature in coping with a crisis: A photographic essay. Landscape Research 26(2): 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Persson D, Erlandsson L, Eklund M, et al. (2001) Value dimensions, meaning, and complexity in human occupation – A tentative structure for analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 8(1): 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen DV, Stigsdotter UK, Refshage AD. (2015) Whatever happened to the soldiers? Nature-assisted therapies for veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder: A literature review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14(2): 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- Searles HF. (1960) The Nonhuman Environment: In Normal Development and Schizophrenia. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Osborne M. (2008) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Smith JA. (ed.) Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. London: SAGE, pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. (2009) Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Mikulincer M. (2006) Trajectories of PTSD: A 20-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter UK. (2013) Nacadia healing forest garden, Hoersholm Arboretum, Copenhagen, Denmark. In: Marcus CC, Sachs NA. (ed.) Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, pp. 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter U, Grahn P. (2002) What makes a garden a healing garden. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture 13(2): 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA. (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2(1): 7–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA. (2001) The psychobiology and psychopharmacology of PTSD. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 16(1 Suppl. 1): S49–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA. (2002) The assessment and treatment of complex PTSD. In: Yehuda R. (ed.) Treating Trauma Survivors with PTSD. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press, pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. (2013) Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]