Abstract

Patient: Male, 73

Final Diagnosis: Gastric intramural hematoma

Symptoms: Bleeding

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Diagnostic/therapeutic accident

Background:

Intramural hematomas primarily present in the esophagus or duodenum. We report a case of intramural hematoma in the gastric wall (GIH) secondary to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement in a setting of platelet dysfunction.

Case Report:

This case study reviews the hospitalization of a 73-year-old male with a history of chronic kidney disease who was admitted for coronary artery bypass graft surgery and mitral valve repair. During his complicated hospital course, he inadvertently required the placement of a PEG tube. His coagulation profile prior to this procedure was within normal limits. The patient had no history of coagulopathy and was taking aspirin 81 mg per day. PEG tube placement was withheld due to an expanding hematoma that was noted at the site of needle insertion in the gastric wall. A single dose of intravenous desmopressin (0.3 microgram/kilogram) was administered under the suspicion of uremic bleeding. No further gastrointestinal bleeding events were observed. A platelet function assay (PFA) and collagen/epinephrine closure time indicated platelet dysfunction. Three days later, we again attempted a PEG tube placement. His PFA prior to this procedure had normalized due to aspirin discontinuation and improvement of renal function. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed an area of flat bluish gastric submucosal bruising at the site of the previous hematoma. The PEG tube was placed successfully at an adjacent site. Over the course of the following month, the patient underwent uneventful feeding through the PEG tube.

Conclusions:

To our knowledge, cases of GIH are rarely documented in literature. Multidisciplinary vigilance is required to maintain a high index of suspicion for this complication in patients with uremia or other coagulopathies to aid in prompt diagnosis.

MeSH Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, Aspirin, Gastrostomy, Hematoma, Platelet Function Tests, Uremia

Background

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is considered to be a safe procedure for establishing a route of feeding and nutrition support in patients requiring long-term enteral nutrition [1]. However, serious complications including bleeding, internal organ injury, aspiration, and perforation can occur in 1.5% to 4% of cases [2]. Gastric intramural hematoma (GIH) is a rare condition usually resulting from coagulopathy, trauma, or endoscopic biopsy [3]. We present the second case report in the literature of a uremic patient who developed intraoperative GIH due to PEG tube placement and was successfully managed with conservative therapy.

Case Report

A 73-year-old Hispanic male with a history of stage IV chronic kidney disease and three-vessel coronary artery disease was admitted for coronary artery bypass graft surgery and mitral valve repair. On post-operative day two, the patient developed cardiac tamponade and subsequently progressed to a cardiac arrest while temporary pacing wires were being removed. Advanced cardiovascular life support and emergent exploratory sternotomy were performed, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further care.

During the patient’s ICU admission, his renal failure progressed, requiring hemodialysis. A nasogastric tube was placed on post-operative day two for establishing early enteral nutrition. PEG tube insertion was suggested given his cognitive impairment and poor swallowing function on the Modified Barium Swallow test. His coagulation profile prior to the procedure revealed an international normalized ratio of 1.04 and partial thromboplastin time of 36 seconds. A complete blood count showed a hemoglobin of 11.6 grams per deciliter, a hematocrit of 34.9%, and 281×103 platelets per microliter. His blood urea nitrogen was 55 milligrams/deciliter, and his serum creatinine was 5.22 milligrams/deciliter. The patient was taking aspirin 81 mg per day due to recent cardiac surgery, but was not on any anticoagulant agents. He also did not have a history of coagulopathy.

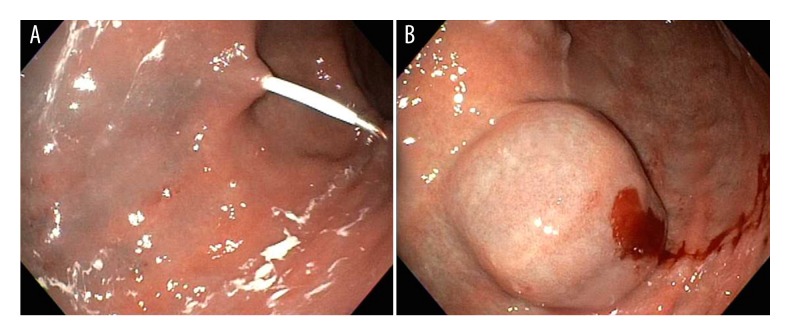

PEG tube insertion was performed on post-operative day eight under intravenous anesthesia. The esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was accomplished without difficulty, revealing diffuse moderately erythematous mucosa without bleeding in the gastric antrum. While attempting PEG tube placement, a rapidly expanding hematoma (Figure 1) developed at the needle insertion site. The procedure was stopped and the patient was sent back to the ICU with a nasogastric tube. A single dose of intravenous desmopressin (0.3 microgram/kilogram) was administered under the suspicion of uremic bleeding.

Figure 1.

(A) First attempt at percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. (B) An expanding hematoma developed at needle insertion site.

No further gastrointestinal bleeding events were noted. To assess platelet function, a platelet function assay (PFA) was ordered after desmopressin injection. PFA collagen/epinephrine closure time was 195 seconds (normal <174 seconds), and collagen/ADP closure time was 76 seconds (normal <120 seconds), indicating platelet dysfunction due to either aspirin or uremia. Aspirin was discontinued, and he was monitored with a daily complete blood count and metabolic panel. Three days later the patient underwent a second attempt at PEG tube placement. PFA collagen/epinephrine closure time prior to this procedure had gone down to 141 seconds, possibly due to withholding aspirin and an improvement in renal function. EGD showed an area of flat, bluish gastric submucosal bruising at the site of the previous hematoma (Figure 2). The PEG tube was placed successfully at an adjacent site. Over the course of the following month, the patient continued to undergo feeding through the PEG tube with no adverse events.

Figure 2.

Second attempt at percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Blue staining within gastric wall at site of previous hematoma.

Discussion

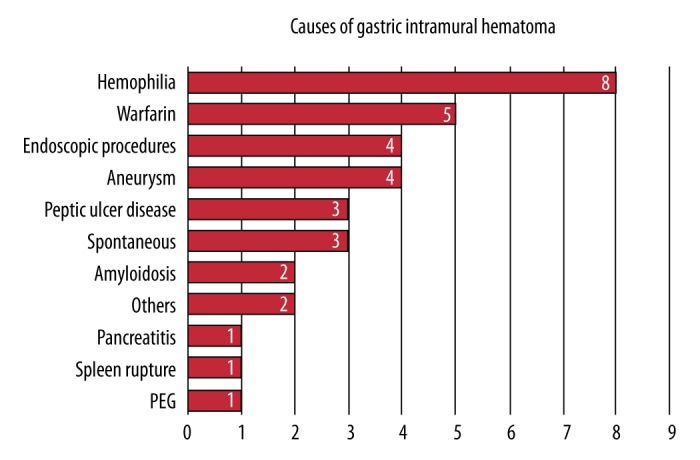

Intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract is an uncommon condition that primarily occurs in the esophagus or duodenum [3]. GIH has rarely been described in the current literature. In addition to 26 cases reviewed by Dhawan et al. [3] in 2009, we found 8 more cases reporting GIH. Jowett et al. reported the only case of iatrogenic gastric wall hematoma by PEG insertion that was managed conservatively in a uremic patient [4]. Hematoma was diagnosed in that patient by endoscopic ultrasound and gastroscopy when she presented with coffee ground hematemesis 6 hours after the procedure. The most common contributing factor to GIH is a bleeding diathesis, including warfarin use [5] and hemophilia (Figure 3). Among all reported cases associated with warfarin use, only one case [6] needed transcatheter arterial embolization, while others were managed conservatively through coagulopathy reversal and blood transfusion. GIH can also result from aneurysm, trauma peptic ulcer, pancreatitis, or spontaneous hematoma [3]. With the development of different endoscopic procedures, cases that lead to GIH following ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy [7], endoscopic mucosal resection [8], or argon plasma coagulation [9] were noted. It is hypothesized that damage to small vessels contained within the deep submucosa/mucosa layer occurred during these procedures, resulting in hematoma formation. All 3 cases related to endoscopic procedures required endoscopic or open surgical interventions to achieve hemostasis. In the current literature, 16 out of 34 (47%) cases required invasive procedures to achieve hemostasis, with most of them having underlying structural damage or abnormalities. In our case, damage to arterioles in the submucosa or muscularis layers during needle insertion possibly led to hematoma formation in the setting of platelet dysfunction. Fortunately, the bleeding stopped spontaneously and our patient didn’t require further intervention.

Figure 3.

Causes of gastric intramural hematoma: 34 cases from 1970–2015. Data were derived from a study published by Dhawan et al. [3] and also from other published case reports [7–9,13–19].

According to a recent published meta-analysis, gastrointestinal bleeding developed in 2.67% of patients undergoing PEG tube placement [10]. While most of these cases can be managed conservatively with placement of packing material, application of pressure, or placement of a stitch at the bleeding sites, damage to major vessels leading to death does occur. One case reported the formation of a fatal retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to injury to the splenic and superior mesenteric veins [11]. Another unfortunate case resulted in death due to perforation of the gastric artery [12].

Conclusions

Learning from this case, physicians should be aware of the risks of bleeding while performing seemingly low-risk procedures. Even with normal coagulation profiles, patients with chronic kidney disease can bleed due to platelet dysfunction. Aspirin discontinuation, although not mandatory before PEG tube insertion, should be considered in patients with a potential risk of bleeding. Endoscopists should be keenly alert of the potential for serious complications during and following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Abbreviations

- GIH

gastric intramural hematoma;

- PEG

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy;

- PFA

platelet function assay;

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy;

- ICU

intensive care unit

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest with respect to this case report.

References:

- 1.Rahnemai-Azar AA, Rahnemaiazar AA, Naghshizadian R, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Indications, technique, complications and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7739–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer KR, Crawley TC. Complications of enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17(4):717–29. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhawan V, Mohamed A, Fedorak RN. Gastric intramural hematoma: A case report and literature review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23(1):19–22. doi: 10.1155/2009/503129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jowett S, Midwinter M, Tapson J, et al. Gastric wall haematoma as a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion. Endoscopy. 1999;31(6):S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Félix RHdM, Galvão BVT, Góis AFT. Warfarin-induced gastric intramural hematoma. Rev Assoc Med Bra. 2014;60(1):16–17. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.60.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imaizumi H, Mitsuhashi T, Hirata M, et al. A giant intramural gastric hematoma successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Intern Med. 2000;39(3):231–34. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itaba S, Kaku T, Minoda Y, et al. Gastric intramural hematoma caused by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy. Endoscopy. 2014;46(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390867. UCTN: E666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun P, Tan SY, Liao GH. Gastric intramural hematoma accompanied by severe epigastric pain and hematemesis after endoscopic mucosal resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(47):7127–30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.7127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keum B, Chun HJ, Seo YS, et al. Gastric intramural hematoma caused by argon plasma coagulation: Treated with endoscopic incision and drainage (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(4):918–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucendo AJ, Sanchez-Casanueva T, Redondo O, et al. Risk of bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrotrostomy (PEG) tube insertion under antiplatelet therapy: A systematic review with a meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107(3):128–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau G, Lai SH. Fatal retroperitoneal haemorrhage: An unusual complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;116(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunai Y, Akaza K, Nagai A, et al. Iatrogenic rupture of the left gastric artery during percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2009;11(Suppl. 1):S538–40. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang C, Yen H. Large gastric intramural hematoma: Unusual complication of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2011;43(S 02):E240–E. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanase Y, Waseda Y, Saito N, et al. [A case of AL amyloidosis due to multiple myeloma presenting with a huge gastric submucosal hematoma during anticoagulant therapy] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;112(6):1023–29. doi: 10.11405/nisshoshi.112.1023. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh YC, Lin CH, Huang SC, Tsou YK. Gastrointestinal: gastric hematoma with bleeding in a patient with primary amyloidosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(3):419. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd T, Johnson J. Intramural gastric hematoma secondary to splenic rupture. Southern Med J. 1980;73(12):1675–76. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198012000-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Procházka V, Válek V, Krejecí I. [Spontanneous intramural hematoma of the duodenojejunal junction mistaken for acute pancreatitis] Rozhl Chir. 2006;85(12):646–50. [in Czech] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisset R, Gupta S, Zammit-Maempel I. Case report: Radiographic and ultrasound appearances of an intra-mural haematoma of the pylorus. Clin Radiol. 1988;39(3):316–18. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(88)80552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimura H, Ohishi H, Inoue K, et al. [Roentgenographic manifestations of intramural hematoma of the stomach in a hemophiliac male (author’s transl)] Rinsho Hoshasen. 1978;23(12):1405–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]