Abstract

Patients awaiting lung transplantation are at risk of negative emotional and physical experiences. How do they talk about emotions? Semi-structured interviews were performed (15 patients). Categorical analysis focusing on emotion-related descriptions was organized into positive–negative–neutral descriptions: for primary and secondary emotions, evaluation processes, coping strategies, personal characteristics, emotion descriptions associated with physical states, (and) contexts were listed. Patients develop different strategies to maintain positive identity and attitude, while preserving significant others from extra emotional load. Results are discussed within various theoretical and research backgrounds, in emphasizing their importance in the definition of emotional support starting from the patient’s perspective.

Keywords: context, emotion, interview, lung, pre-transplantation, qualitative, transplant, valence, wait

Are emotions passive, like sensations, or are they active, like perceptions? Is emotion different in any important way from mood? There seem to be many different emotions, but it is so or is there a small number of pure emotions from which these others are mixed, as all colours result from red, blue and green?

Introduction

In long-lasting or chronic illnesses, emotions – particularly negative ones – have been described in relation to adaptive strategies developed to preserve a sense of normality. This can be achieved in maintaining an emotional balance, in controlling upsetting events and negative feelings and in dealing with uncertainty, feelings of inadequacy and modifications of self-image and roles. Positive relationships within the family are part of the normalization objectives of the ill person to fight against self- and social-depreciation and also stigma (Royer, 1998). Hopefulness, the positive counterpart to helplessness, is an important component of the ability to deal with the negative impact of illness (Zimmerman, 1990).

Among solid organ transplantation, lung patients are often referred to as the population being more at risk of negative emotional experiences and recognized to be especially vulnerable to depressive states; while waiting for a transplant, they have a greater risk of negative physical outcome and of death (Lowton, 2003; Parekh et al., 2003; Shitrit et al., 2008).

In this context, and in a predictive or preventive purpose, most research performed during the pre-transplantation period had focused on negative emotions: for example, anger, anxiety, guilt, depression or distress (Barbour et al., 2006); in lung end-stage diseases, panic attacks can be undifferentiated from physical symptoms. Beliefs of curability/controllability of the disease are related to more adaptive functioning (Howard et al., 2009; Parekh et al., 2003). Important differences in psychological and physical consequences are observed according to the type of initial lung disease. Anxiety (35%), depression (19%) and panic attacks (63%) are reported to be higher in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as they suffer from more disruptive respiratory symptoms. Consequently, a thorough evaluation of the combined effects of physical and psychological aspects should be part of the pre-transplantation follow-up (Taylor et al., 2008).

Before lung transplantation, active coping (dealing behaviourally with stressors), seeking support, avoidant coping or the denial of stressful situations, acceptance of the reality and self-blame are all psychological reactions that have been described before transplantation and appear with a higher frequency in patients when compared with their significant others; emotion-focused strategies (avoidance and self-blame) are correlated with poorer psychosocial aspects of quality of life, and avoidant coping is stress exacerbating and has a negative impact on quality of life and in relationships (Myakovsky et al., 2005). In lung patients, disengagement is associated with depression, anxiety and stress (Taylor et al., 2008). In heart-transplant-awaiting patients, denial and depression correlate with poor adaptive ability (Burker et al., 2005). A qualitative study provides more contrasted interpretation in underlining the importance of working on emotions to maintain a positive attitude and hope towards the future (Lowton, 2003).

Emotions are present in the everyday life of patients: they are known to influence motivation and adaptation to illness. Research often aims at trying to predict illness outcome and survival, and from this perspective, the study of negative emotions is prioritized. However, positive and negative emotions should be considered equally as healthy reactions (Bowman, 2001), and their co-existence or balancing strategies better explored.

Objective

In this institutional review board (IRB)–approved project (Institutional Ethical Review Board affiliated to the university hospital, protocol no 108/02, C. Piot-Ziegler, 2002), the experience of patients in various physical illness conditions and body modifications (prosthesis, implants–autologous breast reconstruction and transplants) was explored. For the transplant patients’ group, a sample of 88 patients awaiting a deceased donor’s solid organ transplant, from the registration on the waiting list, until 24 months after transplantation were interviewed (kidney-, heart-, lung- and liver-transplant-awaiting patients). The objective of the analysis presented here was to provide a comprehensive report of the patients’ emotion descriptions while waiting for lung transplantation.

Methods

Participants

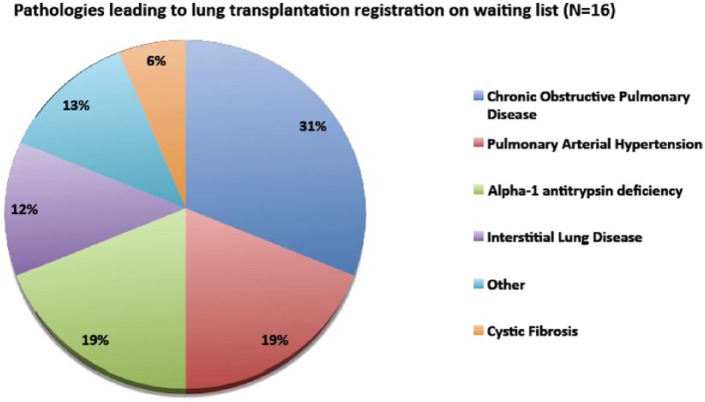

A total of 16 patients were approached by the coordinating transplantation team of the hospital and subsequently contacted by the researchers (N lung-transplant-awaiting patients = 16; men = 9, women = 7; mean age = 52 years, range 27–65 years). The health problems or conditions leading to the decision to register in the transplant waiting list are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Medical characteristics of the patients.

None of the patients was in the situation of re-transplantation. Six patients were receiving support to provide some relief against anxiety: five with anxiolytic treatment (medication), three with psychological support, and among these six patients, two were receiving both treatments. One patient could not be included in the analysis because the audio track of the interview was too difficult to understand in its totality, leaving a sample of 15 patients.

Interview procedure and schedule

Research positioning and methodological choices resulted from different qualitative theoretical and epistemological backgrounds presented in other publications referring to the main project (Piot-Ziegler et al., 2005, 2009). The semi-structured interview schedule did not focus specifically on emotions but on different topics about the patient’s experience of transplantation. Enough space and time of speech was provided to the interviewees to express their own preoccupations and the important aspects from their perspectives, and not only to answer the researchers’ ones: an approach which can be defined as ‘creative interviewing’ used here as giving to the interviewee an ‘active’ part in the co-construction of the interview dynamics and themes development (Holstein and Gubrium, 2003).

Interviews took place between one week and one month after registration on the waiting list: only one patient was referred later, and the interview was performed six months after registration. In order to avoid extra fatigue and stress for the patients or their significant others with an extra commute, adding up to the pre-transplantation medical follow-up, the interviews were proposed at home, what was unanimously accepted. More information was provided about the study when needed, and a consent form was presented for signature. The duration of the interview was not pre-defined and stopped when saturation of information was achieved (mean duration of interviews = 84 minutes ranging between 38 and 132 minutes). They were fully transcribed.

Data analysis

The analysis presented here focuses on the emotion-related discourse and was inspired by different theoretical qualitative research perspectives (Chamberlain et al., 2004, and Joffe and Yardley, 2004 – in Marks and Yardley, 2004; Charmaz, 2004 – in Smith, 2004; Konecki, 1997 – in Strauss and Corbin, 1997). Exhaustive qualitative categorical hierarchical analysis focused on how the 15 patients described their emotional experiences after registration on the transplant waiting list and was performed independently from the main project analytic frame.

The following steps summarize the procedure used in the analysis (the initials of the person who performed the activity appears in the parentheses):

Step 1. Making an exhaustive inventory of all emotion-related descriptions (A.B.);

Step 2. Organizing progressively these descriptions under emotion labelling categories with their valences (A.B.) and discussion of encountered difficulties (A.B. and C.P-Z);

Step 3. Reorganizing the analysis by event or situation (A.B.);

Step 4. Choice of relevant theoretical backgrounds for structuring of the presentation into positive-, negative- and neutral emotion-related categories – and choosing theoretical backgrounds in the emotion literature (C.P-Z);

Step 5. Comparison to transplantation and other research-theoretical backgrounds (‘Discussion’ and ‘Conclusion’ sections; C.P-Z).

The following ‘Results’ section is structured into three parts:

Part A: Description of emotion-related categories by valence or neutral positioning and frequencies of occurrence;

Part B: Theoretical organization of the emotion-related categories;

Part C: Description of the contextual occurrence for each emotion and category.

In the presentation of the results, quotes are proposed to illustrate how patients describe emotions for each category. Attention was taken that all interviewees are represented with quotes ranging from 1 to 6 for each person. No reference to an individual’s identity (even masked) is added to avoid possible cross-match of different quotes for one specific individual: however, references to gender (W – woman; M – man), organ (L – lung), moment of interview in the time-line of the study (E1, before transplantation), page and line are mentioned, although gender differences were not explored. The original language in which the discourse was expressed is French, and quotes have been translated in remaining as close as possible to what has been said and to the meaning of the discourse. Adaptations have been necessary to be understandable in English.

Results

Analysis and structure of emotion descriptions (Steps 1–2)

Part A: Description of emotion-related categories by valence or neutral positioning (Step 1)

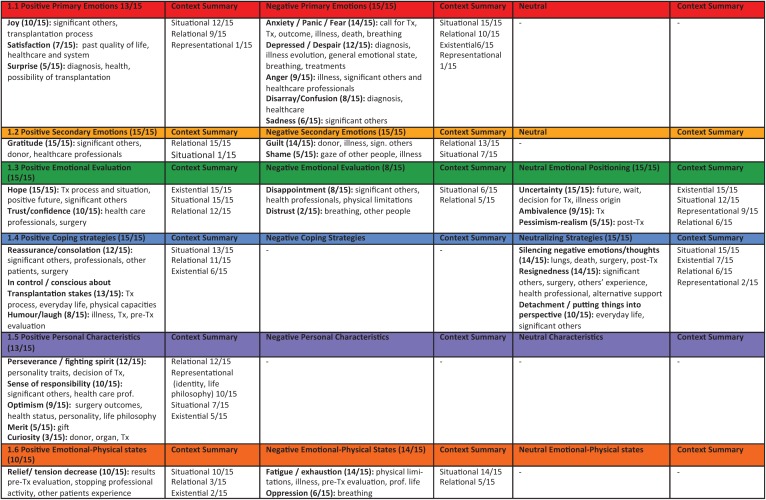

All emotion descriptions were listed under emotion-related categories (N = 32 categories; Table 1) ranging from the most cited categories to the less cited ones (number of patients referring to the category) and by alphabetical order. These categories were then organized into (a.1) positive, (a.2) negative and (a.3) neutral ones, according to the positive/negative valences of the emotional descriptions (Sander and Scherer, 2009; Scherer, 2005) or their neutral underlying positioning.

Table 1.

Listed emotion-related categories by frequency of occurrence (Step 1).

| 1. | Gratitude (15/15) | 17. | Trust/confidence (10/15) |

| 2. | Hope (15/15) | 18. | Ambivalence (9/15) |

| 3. | Uncertainty (15/15) | 19. | Anger (9/15) |

| 4. | Anxiety/panic/fear (14/15) | 20. | Optimism (9/15) |

| 5. | Fatigue/exhaustion (14/15) | 21. | Disappointment (8/15) |

| 6. | Guilt (14/15) | 22. | Disarray/confusion (8/15) |

| 7. | Resignedness (14/15) | 23. | Humour/laugh (8/15) |

| 8. | Silencing negative emotions/thoughts (14/15) | 24. | Satisfaction (7/15) |

| 9. | In control/conscious about lung transplantation stakes (13/15) | 25. | Oppression (6/15) |

| 10. | Depressed/despair(12/15) | 26. | Sadness (6/15) |

| 11. | Perseverance/fighting spirit (12/15) | 27. | Merit (5/15) |

| 12. | Reassurance/consolation (12/15) | 28. | Pessimism/realism (5/15) |

| 13. | Detachment/putting things into perspective (10/15) | 29. | Shame (5/15) |

| 14. | Joy (10/15) | 30. | Surprise (5/15) |

| 15. | Relief/decrease in tension (10/15) | 31. | Curiosity/inquisitiveness (3/15) |

| 16. | Sense of responsibility (10/15) | 32. | Distrust (2/15) |

The most frequent categories are described hereunder (all the categories will be presented in Part B of the analysis). Frequencies and uniqueness or scarcity of the reference to a category by patients are both important in the explanatory strength of a qualitative analysis (Demierre et al., 2011; Piot-Ziegler et al., 2010). Only the most frequent categories are detailed, but all categories appear in Figures 2 to 4. Quotes are proposed to illustrate how patients describe emotions for each category.

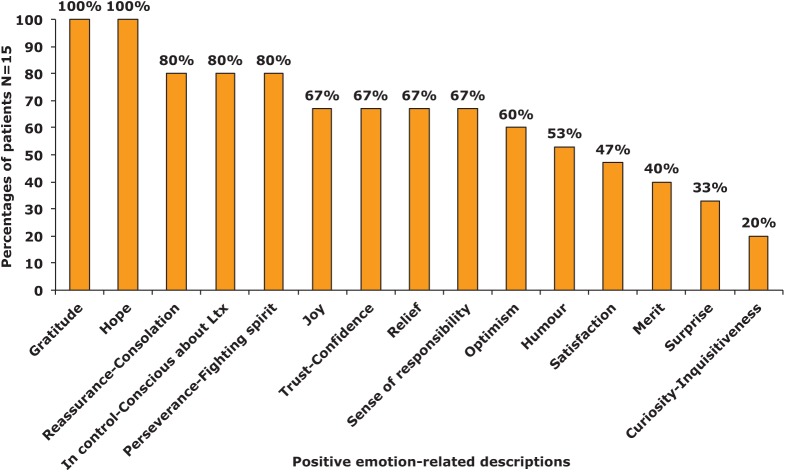

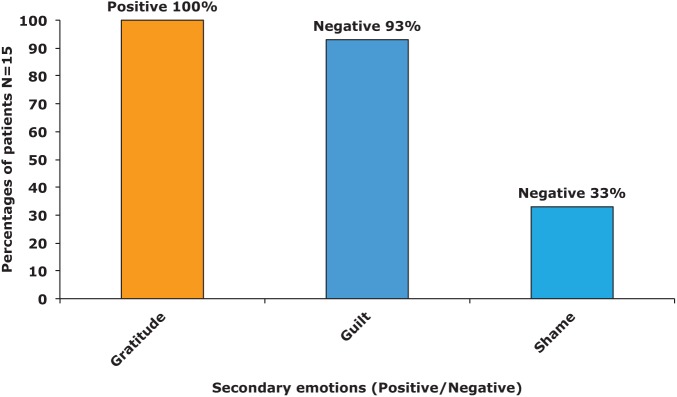

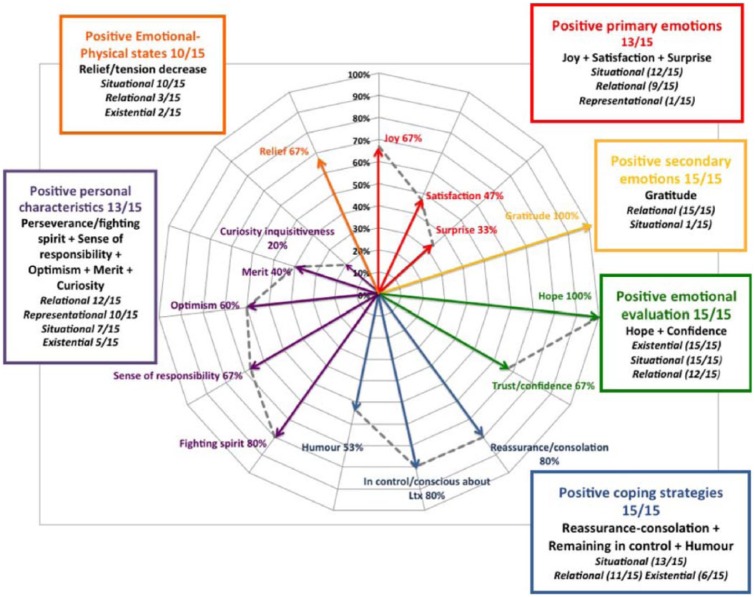

Figure 2.

Positive emotion-related descriptions (Step 2, a.1).

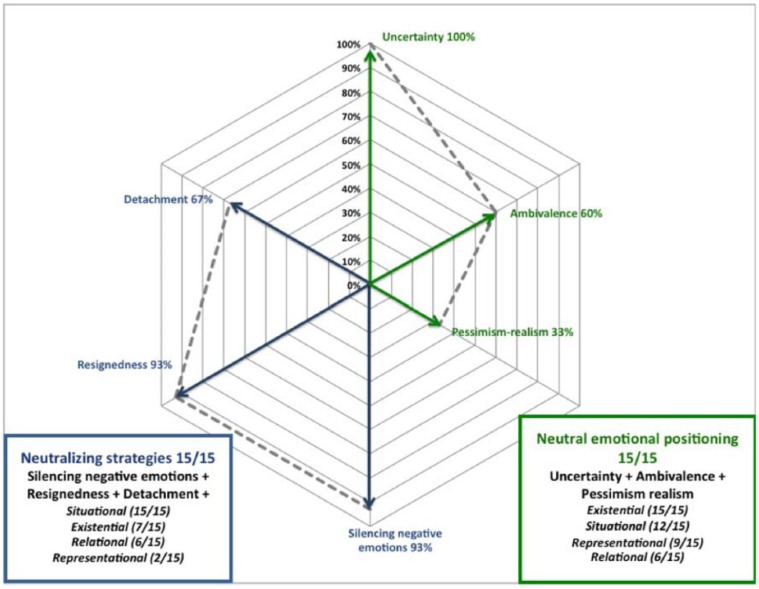

Figure 4.

Neutral emotion-related descriptions (Step 2, a.3).

(a.1) Positive emotions

Positive emotions are extremely diversified (15 categories; Figure 2). The most frequent emotions mentioned by all patients are gratitude and hope (15/15):

Right now, everything is unknown (uncertain) – however, I have my – my little idea about what I’ll do afterwards. Because, I won’t stay there, waiting, until I know if I may catch a cold, if I’ll, – if I’m going to cough. If my table is clean, if I did not forgot to peal my – my fruits. Now I don’t eat salad, never, I love salad so much, so I’ll eat salad the whole – the whole day […] But I already know that I’ll have a clown-life. (W_LE1, p. 11, l.12)

Being in control (13/15), consolation (12/15) and having a fighting spirit (12/15) come next, accounting for the qualities thought to be expected from a lung transplantation candidate or to keep up with, in order to avoid being overwhelmed by the high anxiety-eliciting situation. These categories detail the emotional load going along with the evaluation process and eligibility for lung transplantation:

And in other moments – for example last Thursday, I was doing well, I could climb all the steps from the cellar up without stopping. Ah I told myself ‘But this is great! And I am there, how lucky I am, I can climb all the steps!’ And I told myself ‘Ah finally it is not so urgent. I’m not so bad’ So to say, depending from your physical state, your try to find excuses for – Escapes? Escapes, that’s it. Yes to reassure yourself, it is always that. Well, you imagine different scenarios, whatever the situation is, just to reassure yourself. (W_LE1, p. 14, l.6-14)

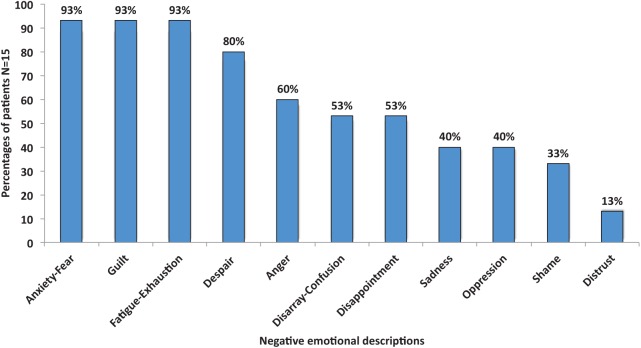

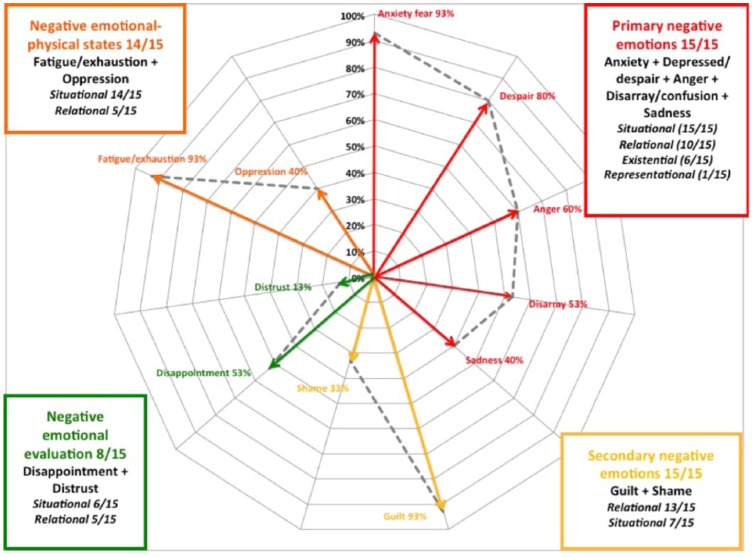

(a.2) Negative emotions

Negative emotions describe the emotions accompanying the everyday life of the patients and also account for the existential questions arising with the stakes and context of deceased donor’s transplantation (11 categories, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Negative emotion-related descriptions (Step 2, a.2).

Anxiety (14/15), guilt (14/15), emotional and physical exhaustion (14/15) and anger/revolt (9/15) against illness and against the inefficiency of the treatments are expressed:

Well, first, it has been a reaction, ehm, ehm, how can I say that, of rage […] towards destiny […] really of rage, because I told myself ‘But oh my God, this cannot be possible’ … (M_LE1, p. 6, l.11)

Despair/feeling depressed/helpless (12/15) are experienced when confronted with the uncontrollability of illness and the unavoidable loss of control in the everyday life activities:

I don’t know either … but I also think that it is related to your body, you had to accept the changes, rather difficult, you cannot do things like before, how did it happen for you? Has not been easy … Not easy … It is not easy, the good thing is that it doesn’t happen suddenly, it comes gradually, I remember it was … at the hospital and there was a physician who told me ‘You will see in a few months you will be just a little thing ‘… on that very moment I was shocked, I told him ‘Perhaps, you are not very clever’, it was hard, but unfortunately, what happens is that, day after day, week after week … you notice that your physical resources are diminishing, it is really perceptible and you rely on everybody, first you try to hide it ah yes ‘Can you just help me ? Could you do that for me?’ Until the day you have to accept that you cannot do things yourself and that you have to ask other people to do things at your place […] and this is not … it is not sudden … I think this must not be easy … No this is perhaps the hardest of it all … (M_LE1, p. 4, l.10)

(a.3) Neutral emotion-related descriptions

Neutral emotion-related descriptions are neither positive nor negative (six categories; Figure 4). They underline the weight of uncertainty (15/15), with the deliberate choice to silence negative emotions (14/15) in order to protect significant others, but also in self-protection to keep negative thoughts at a bearable distance:

Well, I, I must say that I am not afraid, but, but there is a certain, a certain uncertainty, for sure […] you don’t know how, what will happen after surgery, how it will be, of course with each surgery you take risks, but until now these are not things which bother me. I don’t have any problems with that, there is just, a certain, a certain uncertainty. (M_LE1, p. 6, l.42)

Resignedness (14/15) and detachment (10/15) are self-protecting emotional mechanisms, providing the possibility of maintaining cognitive distance with difficult and anxiety-eliciting situations:

… my position had changed (towards lung transplantation) and besides no other option was proposed … and at this very moment, I think it was in March or April … I was professionally on medical leave, I could not do anything anymore, this is not really resignedness, but it is unavoidable. (M_LE1, p. 2, l.50)

Ambivalence (9/15) expresses the stakes of transplantation with no assured success. The proximity of death in the illness course and transplantation surgery risks increase the impression of insecurity:

Well I am pretty reassured, it all right but it is true that, yes, it yes. It is yes, it may be positive on one side, and on the other not easy […] this is for sure weird … But I think I’ll get a better knowledge about that later in my life, if it works … (M_LE1, p. 7, l.25)

In this perspective, pessimism-realism (5/15) is not referred to as a negative state or personality characteristic, but as a factual positioning, when being confronted with the lack of perspectives or future or if transplantation should not occur:

So after that information session, they had informed us about the medication they would use, in underlining that up to today, there is no medication which can ultimately heal us, and that as last resort solution, transplantation was proposed, but it has always been presented as something terrible, problematic, with an uncertain outcome. It has not been presented as a cure at all, as something, which could save us – well for sure, it is true that it saves us, but there was something dramatic which was always associated with transplantation, it was as if between the lines it was like that, because things are not always said. It was between the lines, how it was presented. (W_LE1, p. 1–2, l.42)

Part B: Theoretical organization in emotion-related categories (Step 2)

How to structure emotional experiences before lung transplantation and what do they account for? Attempts to structure emotions have led to numerous theoretical developments (for a review, see Lazarus, 1991). A hierarchical structure of emotions (Dantzer, 1994, classification adapted from Wetzel, 1989) presents the following structure: (a) the fundamental emotions as reactions to an external real or imagined event (e.g. joy, disgust, sadness and fear, they account for what is usually considered as basic emotions), (b) the derived emotions based on the emotion experienced when confronted with another person (e.g. contempt) and (c) the third level emotions, which arise from the feelings experienced when confronted with another person’s gaze (e.g. shame). This three-level structure seemed pertinent and helpful to the organization of the emotional descriptions of the patients.

Apart from disturbing negative consequences, emotions are also associated with adaptive functions: survival, orientation, evaluation, motivation to action and so on. However, authors do not agree on the way of classifying emotions, leading to a great diversity of models and numerous debates (Ekman, 1999, Ekman and Cordaro, 2011; Frijda, 1989–1993; Lazarus, 1991; Sander and Scherer, 2009; Scherer, 1989–1993).

Analysis B organizes the emotional descriptions in six different groups defined in the presentation of the results hereunder: (b.1) primary emotions, (b.2) secondary emotions, (b.3) emotions participating in the evaluation of a situation, (b.4) emotion-cognitive focused coping strategies, (b.5) personal characteristics or descriptions and (b.6) emotional states related to physical states (Figures 5 to 10).

Figure 5.

Primary emotions (Positive/Negative Step 2, b.1).

Figure 10.

Emotional descriptions related to physical states (Positive/Negative Step 2, b.6).

(b.1) Primary emotions

Primary emotions, also called basic, fundamental emotions, are widely present in the patients’ descriptions (Figure 5). The term ‘primary or basic emotion’ does not mean that they are trivial. On the contrary, these emotions have an adaptive value and help a person dealing with usual life-tasks and/or reacting to a specific situation (Ekman, 1999 – in Dalgleish and Power, 1999; Levenson, 2011). They participate to immediate adaptive reactions and comprise happiness (joy), surprise, sadness, fear and anger (Ekman and Cordaro, 2011). Despair and disarray are included in this category, as they are modulations in intensity of sadness.

- Positive primary emotions. Joy (10/15) is experienced with significant others in the everyday life and at the announcement of the possibility of lung transplantation. This sudden opening in treatment options generates surprise (5/15):It was, I don’t find my words, that, really, when they told me … it was really, … close, close, and that something had to be done, and when they told me that I had to go along with oxygen, it was the same thing, and I told myself it is because I don’t have enough oxygenation in my blood, I told myself, it is all the same, it is just while waiting, but I never told myself, ah never, never, I would never have thought that I would have needed transplantation! (W_LE1, p. 1, l.25)

Satisfaction (7/15) is expressed when past quality of life is recalled, when referring to significant others and to the medical care or to the quality of information. ‘And regarding the donor, could you ask all the questions, you, could you … Oh yes […] they answered well to … Yes, yes. (Silence)’ (M_LE1, p. 13, l.17); (Regarding the received explanations on surgery procedure) ‘Did they explain to you well, or … yes it was really well explained’ (M_LE1, p. 9, l.24).

- Negative primary emotions. Anxiety, panic and fear (14/15) are overwhelmingly present and refer to death and to specific situations accompanying lung transplantation: about the future moment of the call and the unknown outcome of surgery. The call for transplantation is imagined as an intense emotional moment, initiating a long and difficult process, full of uncertainties. ‘I wait for this phone call (light breathing) with hope and on the other hand (light breathing) anxiety deep inside!’ (M_LE1, p. 11, l.7):… let’s say (cough), I think about all … I mean … to the stage – the moment when I’ll be called, I, and you know, in the evening, because I have been told that most of the time it is in the evening […] that you are called. When the phone rings, it is right away, my heart pounding […] which occurs (cough). (M_LE1, p. 2, l.40)

Despair/feeling depressed/helpless (12/15) is mentioned when confronted with the diagnosis of end-stage disease, with the occurrence of a moment of acute ‘depression’ (this emotional state seems more contextual and not described as long lasting):

And I came until Christmas not well at all, and having a lot of water, and … they hospitalized me in emergency. And, in emergency, just before Christmas, I came out the day of … the 23rd or the 24th, and, don’t know anymore? Just before Christmas and then, I said that, I saw that I could not go on like that, being to the point I could not move anymore, and I saw the physician and I told him ‘Well, how I am now, I have to accept transplantation I am ready’ I had seen this girl, ‘I have started to make my way’ and he told me ‘Well, no Madam, it is too late, you are beyond transplantation’. So it was one evening at seven o’clock that he told me that and it hit me hard, so hard, violent, it has been really violent for me, and in telling myself ‘Well life is over, there is nothing anymore’ and in telling myself ‘It is not possible, it is not possible, it is not possible!’ and, well, being in (name of a town), my family was not here, so I was feeling really bad. (W_LE1, p. 2, l.36)

Anger (9/15) is related to specific medical events or conflicts with healthcare professionals. Anger is associated with heavy, restrictive medical treatments, practical problems in medical care organization and scheduling. It also describes feelings of injustice experienced, when being confronted with illness and its limitations:

And I had told that, and he told me ‘Well listen, if you reason like that. You know, if in the future, we need to put you on a list for transplantation, well, it will be perhaps difficult. You have to comply with the requirements of treatments’ and all that so at that point, I reacted harshly and talked back.

I told him he was rude to tell me things like that, well I was, young I don’t know, well quite young, 19, 18, I don’t really know. Well, I told him this was not kind, and we somehow (argued) and well the next day, he came to tell me that he did not mean that, well … It was somehow solved, but it is true that, apart from that moment, there has been no other difficulty. (M_LE1, p. 11, l.1)

Being able to express negative feelings provides a possibility to release tension and has a liberating and soothing effect:

No, no I have always been like that without being … well when there is something which is not going right, I tell it, but I won’t shout like … it is for that reason that some- sometimes I react, sometimes depending on … sometimes a little too much and then I realize that … […] sometimes it is necessary […] sometimes it is also a little liberating. (M_L1, p. 11, l.22)

Disarray and confusion (8/15) are experienced as the treatments after the announcement of the diagnosis take time to adapt to and when the difficulties and hesitations of physicians are noticeable to the patients. Transplantation’s dangers and unknown chances of success add up to this uneasiness and generalized existential uncertainty:

I have been told ‘You are really not well, you have emphysema’ I did not even know what it was I was at the bottom of my hospital bed with bottles everywhere in a world I did not know, an environment I did not know, and it took me 10 days to understand what … (M_LE1, pp. 1–2, l.48)

Sadness (6/15) is experienced when thinking about significant others’ emotional and practical overloads or when imagining the possibility of having to part when death would occur:

… you manage to talk about it more in depth together? Well at the beginning it was, it was a little difficult, well, especially with the kids, you don’t know, well the smaller one is six, the third one, it is always quite difficult to have him understand, that well if it doesn’t work, that, that I won’t come back home and that I’ll always be in heaven and that I’ll watch over him (cries) … well afterwards, he cries and he tells me ‘But why do you say that?’ It is true that it is delicate … ‘But well I’ll be an angel … I’ll know how to fly’ […] the older ones, well this for sure, they don’t talk a lot … and well, it is true that, it is, … It is hard yes … Yes, especially for the smallest one, yes. (W_LE1, p. 3, l.23)

(b.2) Secondary emotions

Secondary emotions are not defined as combinations of primary (basic) emotions but as self-conscious emotions or reflections (Eisenberg, 2000; Lewis, 2000) (Figure 6). These emotions occur in an interpersonal realm and comprise social positive–negative evaluations, and, in this perspective, sometimes pressure. They also account for social stigmatization (Ekman, 1999, Lazarus, 1991, and Lewis, 1999 – in Dalgleish and Power, 1999).

Figure 6.

Secondary emotions (Positive/Negative Step 2, b.2).

- Positive emotions. Gratitude (15/15) is expressed towards the donor, the donor’s family and the medical staff:How did you react to the announcement for you? When you have been told, well now you have to think about lung transplantation? Nothing, well morally it is a gift, that the person who is deceased of brain death (makes) because you need brain death so that they can retrieve the organs, well I found that it was a wonderful gift these persons have made, and it is true that it can help a lot of people. Because there are the kidneys, the lungs, the heart … the liver … (W_LE1, p. 6, l.18)

Significant others are also present in these descriptions, as they take up abandoned roles and activities the patients cannot fulfil anymore; they are described as an important resource for emotional support. In this context, gratitude and guilt are very close from one another.

Negative emotions. Guilt (14/15) is overwhelmingly present. However, this emotion must be described in detail, as it is declined in four different ways:

- (a) Guilt towards the significant others (3/15) as illness confronts them to an overload of chores, emotional strains and extra roles to fulfil:Well there is also the other side of it, for my wife it is extremely difficult. Because at the moment … if the work done would pay, in the sense of being freer, having more autonomy on the financial level, being able to go on vacations, travel etc., etc. My wife is also imprisoned inside the apartment. Well … (M_LE1, p. 5–6, l.44)

- (b) Guilt towards the donor and his or her family (8/15), which is associated with the unavoidable death of another person in order to be transplanted and to go on with their lives:But I don’t think that it is the risks or the importance of surgery. It is clear that there is the fact that you are no reassured to go for surgery, because it is heavy, but (there is also) this phenomena of not wanting to speed up … there is always a death behind it all, on the other hand, there is a life which can start again, there is some kind of a dilemma between the two aspects, which is difficult to deal with … some more regarding the donor? … the donor yes, which is a nice word when you think about it for this person, who remains a human being, that you don’t forget … But who has done a choice way before or that a decision has been taken in this direction, the decision is here, you cannot change anything to the condition of the person … Yes that’s right, I admit that … but you neither want to speed that up … nor to … (M_LE1, p. 3, l.38)

- (c) Guilt with the impression of ‘stealing’ a future graft from other patients who will still remain on the waiting list when being transplanted (2/15):I was against it, because I was thinking that I was taking the place – I know – I know quite a lot of children who have cystic fibrosis and I tell myself ‘If somebody has to be transplanted, it is them’ If I was 20- 20 years old, I’ll tell right away yes. But being 60 – almost 60, I tell myself ‘No, me I have lived. I’ve had all I wanted, so I don’t have any other ambition’. (W_LE1, p. 5, l.39)

(d) Finally, guilt is also present when the origin of the illness of the patients could have been voluntarily or involuntarily caused (6/14).

Shame (5/15) is more seldom described, mainly when having to confront the gaze and the negative attitudes of other people. It is harshly and heavily experienced. It refers to painful feelings: when physical changes and external marks of the disease (oxygen bottles, appearance, movement restrictions) are negatively reflected in the eyes of other people:

Because, well, I don’t hide myself, I go to school (with her children) […] but you can see they do not dare to talk about it too much … but it makes, you can feel the gaze […] for you it is a gaze which makes you uneasy towards other people, or which revolts you, […] so well, I told (name) to the older one, I shall perhaps put on a sign ‘Here is what I have, I am not contagious!’ it is true it gives you the impression of that, this is for sure. (W_LE1, p. 9, l.11)

Psychological load accompanies the necessity to abandon certain social roles (family, socio-professional). The consequences of the disease are visible to other persons and bounce back towards the ill person through social uneasiness and misunderstanding. They add up to the physical and psychological disruptive evolution of lung disease:

So that’s it, but … well I hide my, well death, yes you mask certain things … You mask … while arriving slowly, or in arriving before other people or after the others, if you know you need more time ‘Well I go ahead and you will join me later!’ so that they don’t need to wait on me for example […], being invited, well you bring desert because you know that you won’t be able to help clear away the table […] things like that. (W_LE1, p. 20, l.8)

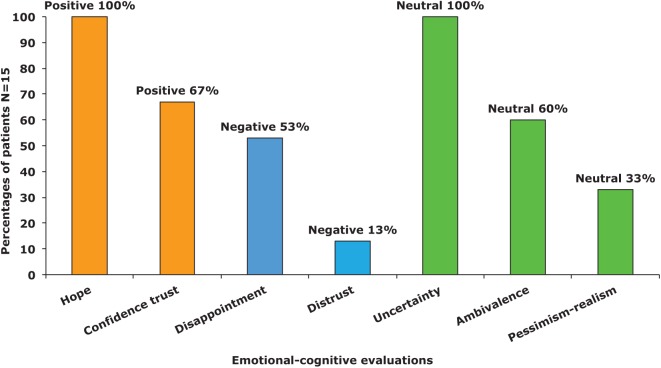

(b.3) Emotions participating in the evaluation of a situation

Emotions participating in the evaluation of a situation are often referred to, using the concept of ‘appraisal’ (Arnold, 1960 as cited in Lazarus, 1966, 1991; Sander and Scherer, 2009) (Figure 7). These categories account for the positive or negative components of a situation, to the barriers experienced when trying to achieve certain goals or to maintain a life balance (physical, psychological and social roles).

Figure 7.

Emotional evaluation (Positive/Negative/Neutral Step 2, b.3).

The goal appraisal theory of emotional understanding (Stein et al., 2000 – in Lewis and Haviland-Jones, 2000; Stein and Levine, 1999 – in Dalgleish and Power, 1999) comprising reasoning and evaluative processes situates emotions in representational, relational, and goal-oriented situations. It allows describing possible discrepancies between mental or emotional appraisal of a situation and personal goals, between beliefs/values and reality. Two aspects are underlined: (a) the harm and benefits, losses and denial, obligations and appropriate behaviours, and the quality of relationships and (b) personal evaluations.

- Positive valence. Hope (15/15) refers to illness and to transplantation, when an opening towards life and a possible future are suddenly available again. It is tempered by anxiety because of the multiple stakes and uncertainties of transplantation:Listen I am really realistic. I know that in my situation, the risks are important, because of my age and because they need to transplant two lungs, but I asked for information to (physician) who has asked the question about the changes if the operation is successful. So he told me ‘Listen, a healthy man of your age has a quality of life of 95%. If transplantation succeeds, you will have a quality of life of 85%, which appears a lot to me’. Which means that I won’t need oxygen, no need for this apparatus anymore … I will be able to walk, at least in my apartment, make small walks. Being able to eat without being out of breath etc., etc., Being able to brush my teeth without problem, to shave without any problem, so this would be something. It would be absolutely fantastic. (M_LE1, p. 6, l.13)

Confidence (10/15) is mentioned in the context of interpersonal relationships and must be differentiated from self-confidence: towards medical care, staff and significant others. With the unpredictable illness outcome, the loss of control on their lives is a painful experience for patients, which forces them to ‘let go’ and to rely on other people:

That’s it. It means that you need to know a certain number of things, but there is a moment when you must tell yourself ‘Well, now, I know enough’ For me at least it is so, it is how I have lived if you want. And from then on, well I have trust and – and – I wait. So I don’t make inquiries anymore, I don’t ask any more questions (laughs) I don’t know because it is recent, it only since two weeks that I am on the waiting list. So it is quite recent. (W_LE1, p. 5, l.26)

- Negative valence. Disappointment (8/15) and distrust (2/15) are discussed regarding physical decrease and breathing difficulties. As physical status worsens, limitations in social activities and in professional duties are unavoidable, however, difficult to accept:No well, (professional) training, well I stopped. So, well it is a little difficult, because, it was important. I had already started a training to become a nurse, I did not succeed to study, after I did assistant nurse, I was really integrated as a nurse, I was always a little … between two chairs. And I told myself, this is not a problem, but I never manage to finish what I had started […] for me it has been a little difficult. Even other people tell me ‘But stop’, for me it is something, which has remained a load […], which has remained on my heart. So I stopped my training, and I stopped at one moment to work. (W_LE1, p. 6, l.7)

These limitations also lead to a lack of understanding from close relatives and from the professional environment. Efficiency of the provided healthcare is sometimes questioned.

Neutral positioning, neither positive nor negative valence: Uncertainty (15/15) is related to physical aspects in particular regarding the origin and consequences of the disease, and as a consequence, leads to the ‘inability’ to imagine the future:

… since the beginning of my illness I took the habit to live one day after the other because I have noticed that otherwise it would have been too hard and that it was really … the impossibility to make projects because if you want, as transplantation is not programmed, you never know what the next day will be made of, so to protect yourself, you have to live like that, one day after the other, and to practice positive thinking. Because otherwise, you would become completely depressed. In this perspective, I must say that the children help a lot, because there is a certain liberated attitude. You talk about other things. (W_LE1, p. 11–12, l.46)

While waiting for transplantation or during surgery, death can occur at any moment. Despite this uncomfortable situation, the transplantation decision is not questioned. At this point, the confrontation with the experience of other persons (patients or persons who already went through transplantation) is not always desired:

Well, it is true that I had asked for a telephone number from a transplanted patient. Because they had told me at the beginning, that if I wanted to have information from other persons, I could. And afterwards, as I had all these problems, about percentages … I did not know. I was a little lost, I asked for a number, they gave it to me, but in fact I never called. Because I told myself, that it is not the same from one person to another other. (M_LE1, p. 10, l.1)

Ambivalence (9/15) is expressed, mainly towards transplantation: although the decision is steadily taken when deciding to live, the proximity of death places the patients with an impossible choice. When not turning towards transplantation, death is waiting at some point in their life-course, but when turning to transplantation, negative outcomes remain possible: ‘Now I am looking forward for the call, but on the other hand, I am afraid because it is a heavy operation, this …’ (M_LE1, p. 9, l.22).

Pessimism-being realistic (5/15) is not to be taken negatively, but as the fact of realizing the seriousness of the situation, in understanding the moral responsibility of lung transplantation and in taking a pragmatic positioning towards donation and the death of the donor. ‘But you see, despite of it all, I am, realistic, that … he/she (the donor) won’t die for me. Well, perhaps – I cannot tell – Perhaps I’ll die first. And they can still retrieve something. So that’s good’ (M_L, E1, p.5, l.15). It is sometimes accompanied with anxiety and refers to a factual evaluation of the reality, of the risks inherent to transplantation for the patients and their significant others:

Then, I think about surgery, even, so … to the surgical risks before or after surgery, because there is a risk of dying, on the operating table … and at this point, I think about my daughter […] I don’t think especially about me, because, well, you must die some day. And … it is … dying on the operating table, it is perhaps the more painless death, finally, as you don’t feel anything […] you are asleep, you go on in your sleep … (M, LE1, p2, l.49)

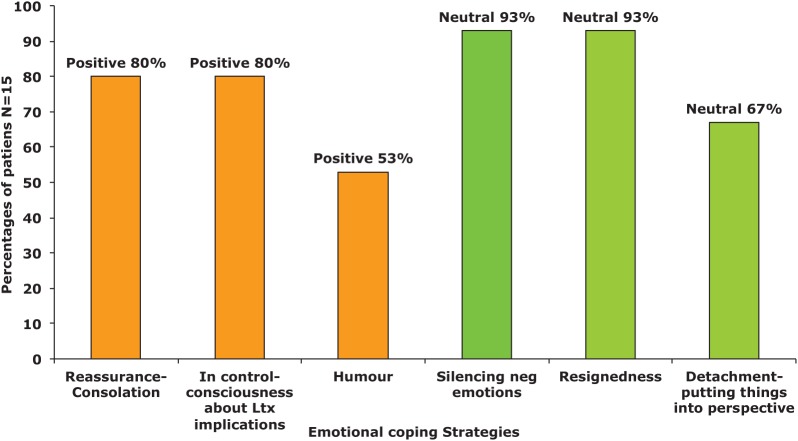

(b.4) Emotion-cognitive focused coping strategies

Emotion-cognitive focused coping strategies refer to all the cognitive, behavioural and emotional strategies developed by an individual to adapt to external or internal demands (Lazarus, 1999; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Sander and Scherer, 2009; Figure 8): (a) problem focused coping, in which the attention is placed on the situation and on the specific actions to solve it, comprising the search for information or an active reorientation, (b) emotion or cognitive focused coping, in which attention is placed on developing thoughts, analysing possibilities to influence, change a situation or a relationship. Constraints influence the ability of a person to make good use of these copings strategies as well as the available personal or social resources (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Sander and Scherer, 2009): (a) the personal constraints (e.g. values, beliefs), (b) the environmental constraints and (c) the intensity of the real or experienced threat, which influences the ability/impossibility to implement these coping strategies although available. Cognitive and emotion-focused strategies are not differentiated in this analysis as the cognitive, physical and emotional contents are closely interrelated.

Figure 8.

Emotional coping strategies (Positive/Neutral Step 2, b.4).

- Positive coping attitudes. Reassurance–consolation (12/15) refers to the need to reassure significant others and to be reassured. The balance between the two priorities is to find, as the negative strains of illness evolve and uncertainties increase while waiting:When the day of transplantation will come, well do you know who will accompany you? Oh it will be my husband […] it is my husband … well my mother will take care of (name of the child) and well I have told them that we won’t go at twenty persons … It will be my husband and that’s it […] but afterwards, I have understood that after surgery, the family had to be quite close (present) to be able to overcome this stage, after surgery … So I told my family that I was expecting them to help me. (W_LE1, p. 27, l.12)

Reassurance is found in gathering information and in maintaining negative thoughts at a distance. The experience of former transplanted persons is sometimes sought but also sometimes avoided. Being confronted with others’ negative experiences may be destabilizing. Alternative supports are also helpful – rites, alternative medicines and spirituality:

And while talking to other persons all around, some friends told me ‘Listen, I know a woman who is doing energetic massages, she work with a pendulum’, ‘You can try homeopathy’, ‘You can go to a healer’ So I mean, I tried all kinds of other things in parallel, to try if you want to delay or- in order to set things in the best possible perspective … (W_LE1, p. 2, l.10)

Remaining in control (13/15) refers to keeping as much as possible autonomy, maintaining a decisional power on everyday-life organization and on how decisions are taken: it is about keeping a decisional, physical and emotional control on one’s life:

You find parries, tricks, it is that in fact, it is the bus, the story of a bus that […] the story of a bus that you take, you run after, you don’t run after but you take the next one […] shopping, it is true that this weekend I had plenty of things … these last two days I stayed still, that’s it, and then … my fridge is empty, but this is not bad […] my washing, it is a little a mess, but well that’s it. It is … I try anyway to hold on with the rhythm. For me, it is important to … not to be overtaken because, I think it becomes more difficult. (W_LE1, p. 11, l.37)

Autonomy is closely related to a positive fatalistic attitude and in trying to deal with things and events ‘how they come’:

… because it is experience, which has taught me, that you have to take things one after the other […] that you must not mix up everything, when I was young I had the bad habit to panic to put a lot of problems in my head, and then to confront them all together at the same time. It is a mistake. So (cough) I want to make one step after the other. My whole energy now is focused on this surgery. First on the telephone, which will ring (laugh). (M_LE1, p. 15, l.18)

The mastery of breathing is also part of this need for control, when this automatic physical function diminishes and is jeopardized:

Except, you don’t think about it, if I take, if I talk with other people, we’ll talk about the brain, about the heart, about sex, you’ll talk about the eyes, but lungs, it is not an organ you talk much about … I am aware about that, as from time to time I cough and I have a lot of difficulty, but it is not, before it was more backwards, a minor organ or another, but which has (now) taken for me all its importance. (M_LE1, p. 13, l.2)

Ultimate autonomy consists in defining what should be done and how, if a negative outcome occurs (severe complications or death). Keeping one’s dignity in death is important:

So, one thing, one thing, which has not been said yet. Well … Before transplantation – before I was told about transplantation, I had told myself, I had promised myself that I would not die laying down. That I would die standing up, this means – it means that I won’t die in a bed, but I want to take part, be fully involved in my – in my – in my death, die with dignity. […] And not like a wreck and not lay down – and if I don’t get a transplant – it is what will become more difficult now, because I have had a glimpse of something else – I hope that I’ll be able – to find this line (direction) again, and tell myself ‘Well, the graft doesn’t come, and I decline. Well, it is not possible anymore, like – perhaps somebody will come and tell me ‘It is not possible to transplant you anymore’. And I hope that I’ll be able to find this uprightness I had before, I told myself ‘Well (her name), it has not been possible. You have tried. You have done everything. It has not come. It is not your fault. That’s life, it is like that. You have received. You have lived it fully. Now, keep up your dignity until the end.’ And this – I hope that I’ll be able to live it like that […] That I won’t become an old grouch, an old bore’. (W_LE1, p. 22–23, l.50)

Having a sense of humour (8/15) is a way to deal with a difficult situation. It shows that patients have psychological resources and keep up with a positive attitude:

It is a game, it is a game as there are things in life I like, and others I don’t like too much … so when I’m told that I won’t be able to do things I like, it bothers me, and overall, I laugh with (name) or the kids on … things I hate, which I won’t be able to do. Like, I’ve been told ‘You won’t be able to go to the swimming pool’ I had a smile, until now it hasn’t bothered me at all, but … but these are simply the facts, you take them one after the other, some give you pleasure, others less, and that’s it, that’s all. On these aspects you make fun, but that’s all. (M_LE1, p. 8–9, l.45)

Neutralizing or soothing coping attitudes. Silencing negative emotions (14/15) is a way to keep anxiety at a bearable intensity and to deal with the body and lungs’ dysfunctions. The threat and stakes of surgery are constant reminders of the proximity of death. The precise moment when the patient will wake up with another person’s lung(s) is intellectually difficult to imagine:

For me, it is perhaps funny what I am going to tell you, but for me, at least until now, it has never been a problem … emotional, or … a really important problem, an ethical problem, etc … I never had this perspective until now. For me, it was more a question on an intellectual level: advantages, disadvantages, risks […] it may change, this is for sure. I imagine, from the moment you wake up, with the lungs of another person […] it is perhaps different […] I think that I am going to see the problem in quite a different way, but right now on a mental (cognitive, representational) level like this, it does not exist. (M_LE1, p. 3, l.34)

Negative situations, experiences or information are not eluded but avoided to remain positive despite all uncertainties:

But I prefer, not to confront these problems, if, if these problems are… perhaps later […] yes I prefer for the time being, to think, to concentrate on what will follow, now. Later, we’ll see. It depends on how I’ll react, when having, new lungs, you know … (M_LE1, p. 14)

As control is limited and as no other alternative is available when confronted with the negative evolution of the disease, resignedness (14/15) is often underlined. To compensate for the diminishing capacity of breathing, the use of an oxygen-dispensing device provides some relief as physical oppression increases:

Me, well, I had difficulties to accept, it took time to have me accept. And after, I have worn it (oxygen dispenser), and now what I tell myself, is that I wear it to spare my heart, it is what helps me go further on […] And I know that I have to wear it. If I wouldn’t have oxygen during the night, I would not feel well. (W_LE1, p. 10, l.14)

Detachment and trying to put things into perspective (10/15) are part of the chosen attitudes in various difficult situations: the negative evolution of the disease, the wait for the availability of an organ (and transplantation) and in social relationships. Keeping emotional distance helps to deal with uncertainty and not being overwhelmed by anxiety. Focusing on true values and setting existential priorities are important:

Yes, it is true that, yes. It begins, it is true, to change, for sure, I could tell on what, it is true that small problems of the everyday life, I have no example but […] Yes it is true that you put things into perspective. […] that’s it. Yes, it is true that before, I gave more importance to material things, at least a little, put that into brackets, but my father is a little like that, I have taken that from him, but it is true that I tell myself ‘Yes, I don’t care’ In reality, no, I do care, I am careful, it is true that would rather give, that’s true I change a little. Slowly but … (M_LE1, p. 5, l.28)

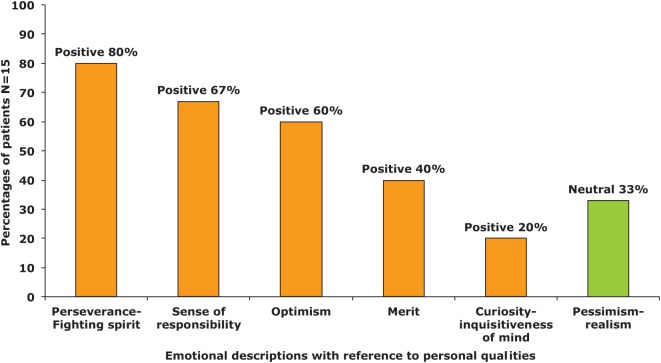

(b.5) Personal characteristics and qualities

Personal characteristics and qualities influence positively or negatively a person’s health (Figure 9). They are described in different models: sense of coherence (SOC) model (developed by Antonovsky, 1987, 1996) and ‘salutogenesis’ model (for a review, see Geyer, 1997; Pallant and Lae, 2002). Concepts such as self-esteem and optimism are associated in stressful situations with better coping or better illness outcomes (Antonovsky, 1987; Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2005; Geyer, 1997; Smith et al., 2013). All these aspects have been widely used in research and in health interventions (Langeland et al., 2007).

Figure 9.

Emotion descriptions related to personal characteristics (Positive/Neutral Step 2, b.5).

- Positive characteristics. Having a fighting spirit (12/15) is mentioned as a necessary personality characteristic helping the patients on the way to transplantation, but also participates to the fact of being able to help significant others:But first you must be ready to support yourself. […] Because otherwise, it is no use, if you are not convinced about that, all what is around would be, would be […] You understand? You must be first convinced that you can try to do something, and then, the support of the significant others piles up with, with ours, and it increases more and more, hopes […] strengths. (M_LE1, p. 18, l.3)

As physical limitations and outcome uncertainties are present in their everyday lives, being high spirited and remaining positive are extremely important for the patients. The perspective of being able to breathe freely after the occurrence of transplantation helps maintaining this positive attitude towards the future until the moment comes:

But it will be hard, yes […] on the contrary, if you have, if you breathe in a completely different way, in being calm, breathe normally, without oxygen, without apparatus, so I imagine that it gives, in the perspective of motivation, it is a really good situation […] you really have to go for it fully, it is what I’ll do. (M_LE1, p. 13, l.3)

Sense of responsibility (10/15) refers to the extra load weighing on significant others in the context of the negative evolution of illness. For patients, it is also dealing with how to fight actively against these negative consequences. It encompasses the acceptance of support, putting into parenthesis their former identity and abandoning unconstructive pride. Loss of independence is a difficult experience to deal with. The feeling of being a burden to other people (healthcare professionals or significant others) leads some of the patients to avoid disclosing their difficulties or concerns:

And the fact that he/she is dead (talks about the future donor), this goes all together, so it is for this reason that I don’t want to, as long as I have drains all over, me, I don’t want to see anybody (talks about the intensive care after surgery). More for them than for me, because it seems that you (will) forget the time you have been in the intensive care, you forget all the visits … everything what happened, it seems, so I don’t really know […] You want to protect them from […] […] me I don’t want to worry people around me oh no, me, I would like, I try to avoid taking advantage of them, the less possible, first because I am not somebody who, I don’t like to be, like to be dependent on somebody … (W_LE1, p. 12, l.2)

Responsibility is also taken in making the decision for transplantation alone and in planning practical aspects if negative outcomes would occur during transplantation surgery:

And I think also that after surgery, if I become a wreck, it can happen, for some reason or another, and I am here, and that somebody has to feed me, to wash me, so at that point, and that I’ve told that, not to take the liberty of other people, at that point I prefer to go away. (M_LE1, p. 20, l.23–26)

Being optimistic (9/15) is related to the hope that transplantation will be an opening to life. It leads patients to set new priorities and to focus on what is essential in life, in relationships and towards existential reassessment. The present moment is favoured as well as positive relationships and simple pleasures:

I have also problems in front of other people to … with certain discussions, because it seems that people are really overwhelmed with small things, so – this is perhaps the advantage. It is because you evolve a lot, if you, you, put things into perspective, because you come to the point that there are things – for me it is to live simply, I mean this is my objective. So for sure, I don’t have the same objective than other people, and I see things very differently. You come also to the point you go into great raptures over very small things. The day I’ll be able to do 100 meters without being tired or without being out of my breath, I’ll tell myself ‘Ah, but this is wonderful!’ And I’ll look at a small blade of grass and I’ll find it extraordinary … (W_LE1, p. 8, l.42)

Deserving to be transplanted – merit (5/15) relates to donation and to the difficulty associated with receiving an organ: the death of the donor, the uncontrollability of organ attribution for the patient, the ‘aptitude’ (eligibility and physical-psychological readiness) to receive an organ and, finally, its future acceptance. ‘The graft (transplantation), me I accept it. As I say, for me, it is, I do deserve it, because, I did not do it on purpose, of, so, so, I do deserve it and that’s it!’ (W_LE1, p. 10, l.27)

Curiosity–inquisitiveness of mind (3/15) deals with various questions about the donor, the integration of the organ and about the process of transplantation: ‘And at this point, I wait my, my own reaction, the moment when you experience living with the organ of another person …. […] I think, I think it won’t cause a lot of problems’. (M_LE1, p. 9, l.19)

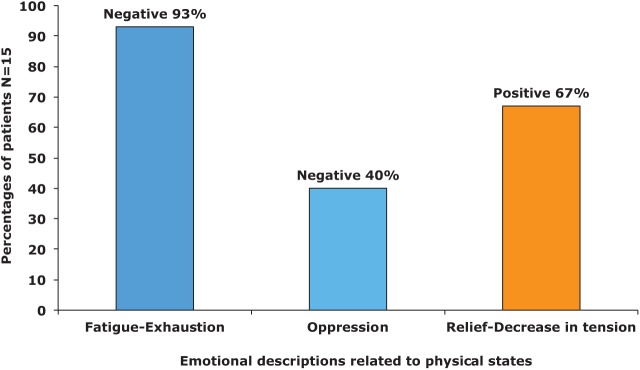

(b.6) Emotional states related to physical states

These categories present specific emotional states related to physical aspects (breathing, relief) or associated with medical status, events and treatments (Figure 10).

- Negative valence. Fatigue and exhaustion (14/15) are present in almost all the patients’ discourses, associated with the inability to perform simple daily activities. Details are given on all aspects, which patients have to give up. Daily life shrinks like the pulmonary capacity and the ability to breathe freely:So … Absolutely, I came to this point because everything I do, is related to that, in telling myself ‘Shall I be able to do that?’ etc. So I do the minimum now, that means I do the taxi for the children, but well, I don’t even get out of the car, you see? So they know that I am coming at this or this place, the car is here, they get in, they get out, etc. Or I go out to do some shopping, because this you have to do sometimes, even if it is my husband who takes care of the groceries, but … things for my pleasure, it doesn’t exist anymore … (W_LE1, p. 8, l.10)

The difficult balance between what is considered to be a supportive social environment is discussed, and compared to the possible extra burden or source of exhaustion of non-adapted demands or attempts to help. The lack of understanding from healthy people is also described: ‘Yes, you always have to find the right words, and be short, and always repeat the same things and then, there are people you want to tell about, others no’ (W_LE1, p. 7, l.12).

The stressful context of the pre-transplantation physical evaluation is underlined, as its exhausting consequences:

No, no, not like a fight, but in these circumstances, as there is not much mobility left for me, as my breathing has become difficult, it was quite hard. Especially, this whole succession of tests, this, I found pretty hard […] quite tiring yes […] yes, yes, physically. (W_LE1, p. 2, l.30)

Oppression (6/15) is referred to as a constant reminder of the vital importance of breathing. The impression of being limited in lung capacity is associated with the fear of suffocating: ‘I have the impression that I find myself imprisoned in a vice […] So tight, that there is no space left’ (M_LE1, p. 3, l.31):

Ah, I – I don’t have blockages (spasms) like people who have asthma, but it is true that as soon as I make a physical movement, a little too violent, I am in shortage of energy and I’ll pay for that later. And I know that, so, if I climb up two steps too much, afterwards, I am folded in two, and I search for – I search for air, and I panic because during 2–3 seconds, there are a few seconds, which will be worse, and I know that … and this is very heavy (difficult), in the perspective that I know what to expect, if you want. And sometimes, I really feel bad, I cannot even look, for example, at TV broadcasts about diving or something like that. You feel oppressed when looking? Oh yes, yes. Or when being in small abode, I know that I have to take my breath way before, before getting into a car because it will be like a panic – or before lying down – I know when I lay down like that, that there will be a difficult moment. So I know myself quite well, I mean, I know the positions, which are comfortable for me, I have to take, to spare myself, to avoid the – the attack. (W_LE1, p. 13, l.29)

- Positive valence. Relief (10/15) is experienced when the diagnosis about illness is posed, and when after all the evaluations, the decision of registration on the waiting list is finally taken. Being freed from certain professional or daily activities is welcomed:The coordination nurse told me ‘Madam […], now you can consider that … in a quarter of an hour, you are on the waiting list, I’ll do what is needed’. So at this moment it was … wow […] wonderful […] a relief yes really […] Yes completely, yes, because, staying like that, I won’t live on very long. (W_LE1, p. 8, l.28)

Part C: Description of the contextual occurrence for each emotion-related category (Step 3)

Each contextual occurrence of the emotion-related descriptions (Step 3) is detailed in Figure 11, with its positive, negative valences or neutral positionings. Although available and different from the previous sections’ ones, no further quotes are presented here. The emotion-related descriptions can be differentiated in four different contexts:

Figure 11.

Context of occurrence for each emotion-related category and by valence (Step 3).

Situational contexts refer to specific situations where emotions are experienced such as healthcare, illness limitations or evolution, everyday life activities, pre-transplantation evaluation, transplantation decision;

Relational contexts refer to all the emotional descriptions experienced in the context of interacting with other people, such as significant others, healthcare professionals, patients who already went through transplantation;

Representational-conceptual contexts refer mainly to the topic of donation, with emotions arising, when reflecting upon the conceptual aspects of donation, or when being confronted with the paradoxical situation of transplantation as the death of the donor co-exists with an opening to life for the recipient or when having decide to register for transplantation;

Existential questionings contexts, refer to emotional descriptions appearing when the person is confronted with life questionings, existential values or life stakes, and personal physical or psychological challenges while waiting for transplantation.

(c.1) Contexts of primary emotions (appearing in red,Figure 11)

Primary positive (13/15) and negative (15/15) emotions refer to situational (positive 12/15; negative 15/15) and relational (positive 9/15; negative 10/15) contexts. For negative emotions, existential questionings (6/15) are also present. For specific emotions such as anxiety and despair, they are mainly associated with situational contexts. These emotions are immediate reactions to illness contexts, stages and impact, with their relational consequences.

(c.2) Contexts of secondary emotions (appearing in yellow in Figure 11)

Positive (15/15) secondary emotions appear within relational contexts, with for all patients the expression of gratitude towards their significant others, the donor and healthcare professionals. Negative secondary emotions (15/15) are also associated with relational contexts (13/15); however, they account for the impact of the intellectual and emotional load of deceased donation and of illness (12/15). They also refer to illness-related situations (7/15) and express the emotional load of the attitude of other people with their misunderstanding of transplantation (8/15). In this category, emotions are described as reflexive processes in relational dynamic contexts. They underline the importance of the social influence from significant others and healthcare professionals. They also account for the delicate and changing balance between positive, negative and neutral emotional states, with their consequences on the patient’s self-perception and on the emotional tonality of his or her relationships with other people.

(c.3) Contexts of emotional evaluation (appearing in green, Figure 11)

Positive evaluations (15/15; hope and confidence) refer almost equally to existential (15/15; better future), situational (15/15; process of transplantation) and relational aspects (12/15; health professional and hope for their significant ones). Positive relationships with other people must be preserved and oriented towards persons with whom positive outcomes can be expected (significant ones, professionals and other patients). Negative emotional evaluation (8/15) is situational (6/15) and expresses the disappointment towards growing physical limitations in everyday life situations, which leads to relational (5/15) difficulties with significant others or healthcare professionals, as the adequacy to provide the required/needed care is more difficult to reach. Neutral positioning (15/15) refers to existential (15/15) and situational (12/15) contexts as future is uncertain and as the representation (9/15) of life and death in the context of transplantation and donation is difficult to confront. It refers to taking a pragmatic positioning as events and control on health evolution and transplantation occurrence are out of the hands of the patients. Relational (6/15) aspects are also present and are associated with the experience of other persons or the implication of significant others in the evaluation of the transplantation decision. Evaluation processes are closely associated with existential questionings, which underline the stakes and existential re-evaluations of life and death while waiting for transplantation. In this context, neutral evaluations account for the confrontation of the patient to the uncertainty and unknown outcomes of transplantation.

(c.4) Contexts of emotional-cognitive coping strategies

Positive coping strategies (15/15) are situational (13/15), relational (11/15) or refer to alternative ways of dealing with existential questionings (6/15) in developing control strategies and holding on reassurance.

Neutralizing and soothing coping strategies (15/15) are mainly situational (15/15) and are part of a detachment process in a situation, which is depending on the evolution of illness and on the possibility of being transplanted. Neutralizing strategies help to deal with existential questionings (7/15) and uncertainty. However, they may also lead to a relational gap (silencing negative emotions) between the future transplanted persons and their significant others (6/15). The descriptions of the available coping strategies show that the patients have important resources to handle situational and relational problems. They also give interesting cues on how and when these strategies are implemented. Neutralizing strategies take an important part in dealing with uncertainty. They should, however, be closely scrutinized, as isolation and inability to express negative emotions could result from these a priori resilient strategies.

(c.5) Contexts of personal characteristics

Positive characteristics (13/15) refer mainly to relational contexts (12/15) which are also very much present with a strong feeling of responsibility towards significant ones, with the abandonment of family and socio-professional roles. Positive personal representation (10/15) is important and appears in specific situations (7/15), in which a high-spirited attitude helps in maintaining a positive identity and a positive perspective on life. A balance must be found between the acceptance of other people’s help, and the desire to keep one’s independence and autonomy. These positive personal characteristics are also described within existential positioning or life philosophy (5/15). These high-goal personal characteristics put an extra psychological pressure on the future transplanted patient and must be well monitored. These descriptions, overwhelmingly positive convey the positive image the patient wants to keep up with and may be considered as resilient strategies. However, they could also be the expression of the framing image of an ‘in-control good transplant candidate’ leaving few possibility of expressing weaknesses and doubts. The thin line between a necessary positivity and optimism, and the exhaustion of the personal, interpersonal resources support should be closely monitored during the waiting period.

(c.6) Contexts of emotional states related to physical states

The occurrence of these descriptions is for negative ones (14/15) situational (14/15) when trying to deal with illness consequences and breathing difficulties. More seldom they are related to the relational impact of exhaustion and fatigue (5/15). Positive (10/15) descriptions are mainly situational (14/15) when the mastering of a difficult situation is achieved, when referring to other patients’ positive experiences (3/15) or alternative existential ways of dealing with uncertainty (2/15).

(c.7) Categories, context and valences: a summary

The detailed account and categorical organization of the emotional descriptions with their valences (summary Figures in Appendices 1 to 3) help us understand where the stakes and central questionings arise and show that they are associated with very specific contexts of occurrence: situational, relational, representational-conceptual and/or existential.

Usually, negative emotions are under scrutiny in psychosocial or interventional studies. However, positive emotions and neutralizing emotional processes may well be extremely useful for balancing negative consequences of illness evolution or stakes.

Negative emotional descriptions (Figure 12, Appendix 1) are mainly situational and relational. They refer to specific situations/events, as well as to physical strains and limitations. Guilt and shame, although widely referred to, do not only relate to the context of donation but also to the intellectual load of the deceased donation context and of transplantation, to the weight of illness on significant others and to the social misunderstanding of transplantation in general. They are also associated with existential questionings about life values and death threats. Negative evaluation occurs when the patients are confronted with the discrepancy between what is needed and the actual help available or provided. Finally, acute negative emotions are associated with very specific situations, with severe negative physical states and their unavoidable consequences on relationships with other people.

Positive emotional descriptions (Figure 13, Appendix 2) and states are certainly representing resources, which help counterbalancing the negative emotions. They are mainly related to situational and relational contexts. All categories are represented. In terms of relational contexts the emotions cited regarding professionals are not similar (gratitude, confidence, reassurance ‘from’) to the ones reported with significant others (joy, gratitude, hope, reassurance ‘provided to’). Positive existential descriptions refer to questions arising from the opening to life, and the associated human positive life values. Positive personal characteristics help maintaining a positive attitude/image, despite the pre-transplantation stressful context. A positive attitude may also be part of the ‘thought to be’ image of a ‘responsible, in control’ patient.

Neutral or neutralizing emotion-related categories (Figure 14, Appendix 3) refer to soothing strategies implemented as personal coping strategies and to preserve significant others. Existential questionings (future, life/death, decision for transplantation) and a neutral (fatalistic) attitude towards the donor, illness and transplantation outcome are part of a general reflection about life and death. Emotional soothing strategies are situational and existential; they are implemented in situations where life and death stakes are present or uncontrollable events are experienced, as cognitive-related strategies (detachment or putting things into perspective), but the latter also help dealing with aspects of transplantation which provoke representational difficulties: the transition between the death of the donor and life for the recipient, and the existential transition of the transplantation as event.

Maintaining a balance between these different emotional states and adapting to their rapid evolution is certainly one of the most difficult challenges of the pre-transplantation period.

Discussion

Descriptive level and interpretative level are more difficult to differentiate than it seems. We tried to show the complete process of the construction or our data analysis. Theoretical backgrounds out of the emotion literature helped to organize the analysis and the emotion categories. Without that thorough organization and structuring, the analysis would have remained only descriptive and would have presented the emotional categories as discrete categories with no relations or significance as per their adaptive functions. Based on that thorough analysis, the contextual occurrences of emotions take all their importance:

For better understanding in a research and theoretical perspective;

But also in giving tools for defining the type of interventions and psychological support.

Our analysis accounts for one of the multiple possibilities of entering into a rich qualitative corpus, and has imposed itself after other analytical entrances into the available data (see other cited publications from the senior author). Emotion descriptions seem to be a ‘revealer’, an ‘enhancer’ of the experience of the patients awaiting lung transplantation. Such a comprehensive analysis could not be avoided or summarized, when uncovering and discovering not only the richness of these descriptions but also their sensible articulation and functions in the everyday life balance of the patients’ fight for life.

In this research, we have also explored different possibilities of (re)presenting qualitative data and their analysis: with quotes as examples, in summary tables, histograms or ‘radar’ figures, with their respective limitations, biases and inherent difficulties.

Although the complete presentation of the structuring of the analysis may seem fastidious to the reader and could appear to be only descriptive, it is neither trivial nor without underlying interpretative process. Giving a detailed account of the interviewees’ discourse on emotional descriptions, and showing its richness, not only in content but also in its internal complexity was in our perspective important in order to be able to communicate the intensity of the patients’ experiences before lung transplantation. Limitations can be addressed about the choices and perspectives proposed here; each reader will pose his or her own critical viewpoint.

This analysis and its presentation lead to further questions in the emotion field, which are discussed hereunder.

Is emotional experience before lung transplantation only negative?

In transplantation, most of the research focuses on negative emotions, to prevent ‘mental morbidity’ or in using depression as a predictor of psychological fragility (Dobbels et al., 2006). The lack of clear evaluation or differentiation between anxiety and depression or stress in transplantation (Rapo and Piot-Ziegler, 2013) and in other illness contexts is also extensively discussed (Bowman, 2001; Szabò, 2011).

The results presented here show the rich emotional discourse of patients after registration on the waiting list and underline that lung transplantation is accompanied by intense and complex emotional experiences. Emotions have a real importance and they do participate to the mind-body balance in a difficult health context (Piot-Ziegler, 2012). The influence of positive and negative emotional experiences remains to be explored in detail (Hershfield et al., 2013; Jain and Labouvie-Vief, 2010) as they influence motivation and physical well-being (Roseman, 2011), especially in illness contexts. Some of these aspects are evaluated in questionnaires (Pallant and Lae, 2002).

The positive effect of the ability to differentiate and keep separate positive emotions from negative ones has been previously underlined (Zautra, 2003; Zautra et al., 1997, in Zautra et al., 2001) as has the importance of their balance and continuity (Gross, 1999). The ability to clearly differentiate between negative emotions seems to participate in healthy functioning and regulation processes and as a consequence, well-being in non-illness-related samples (Erbas et al., 2014).

In lung transplantation, detailed qualitative descriptions are lacking. In this analysis, interviewed patients are able to differentiate and give precise accounts of their positive and negative emotions. They do not present a poor ability of introspection about their emotional experiences. The term ‘emotional awareness’ has been used (Bydlowski et al., 2003) in accounting for the ability of a person to represent himself or herself, his or her own emotional experience and the experience of other people. Clarity defined as the ability to talk clearly about emotional states, the ability to take emotions into account and the concept of emotional ambivalence are also reported (Mayer and Salovey, 1995). In our results, ambivalence is associated with situations in which difficulties are encountered during an evaluative and decisional process. Positive or neutralizing processes and proactive personality characteristics are also referred to (e.g. realism; optimism, cited in Goetzmann et al., 2008). All participate in maintaining a positive attitude while waiting for lung transplantation.

How is emotional intelligence present in the discourse of patients before lung transplantation?