Summary

Background

Deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) is an underdiagnosed entity characterized by pain and/or dysesthesias in the buttock area, hip or posterior thigh and/or radicular pain due to a non-discogenic sciatic nerve entrapment in the subgluteal space. Multiple pathologies have been incorporated in this all-included “piriformis syndrome”, a term that has nothing to do with the presence of fibrous bands, obturator internus/gemellus syndrome, quadratus femoris/ischiofemoral pathology, hamstring conditions, gluteal disorders and orthopedic causes.

Methods

This article describes the subgluteal space anatomy, reviews known and new etiologies of DGS, and assesses the role of the radiologist and orthopaedic surgeons in the diagnosis, treatment and postoperative evaluation of sciatic nerve entrapments.

Conclusion

DGS is an under-recognized and multifactorial pathology. The development of periarticular hip endoscopy has led to an understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying piriformis syndrome, which has supported its further classification. The whole sciatic nerve trajectory in the deep gluteal space can be addressed by an endoscopic surgical technique. Endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve appears useful in improving function and diminishing hip pain in sciatic nerve entrapments, but requires significant experience and familiarity with the gross and endoscopic anatomy.

Level of evidence

IV.

Keywords: hip arthroscopy, hip endoscopy, sciatic nerve entrapment, deep gluteal syndrome, piriformis syndrome, ischiofemoral impingement

Introduction

Posterior hip pain and sciatica in the adult are among the more common diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for orthopedists and radiologists. To date, reports including the term “deep gluteal syndrome” (DGS) in orthopedic and radiologic journals have been limited, however, many articles discuss or focus on piriformis syndrome. In this article, the anatomy, clinical findings, pathophysiology, etiology, and management of DGS are discussed.

Subgluteal space anatomy

The subgluteal space is the cellular and fatty tissue located between the middle and deep gluteal aponeurosis layers1,2. This space is anterior and beneath the gluteus maximus and posterior to the posterior border of the femoral neck, with the linea aspera (lateral), the sacrotuberous and falciform fascia (medial), the inferior margin of the sciatic notch (superior), and the hamstring origin (inferior). At its inferior margin it continues into and with the posterior thigh. Laterally it is demarcated by the linea aspera and the lateral fusion of the middle and deep gluteal aponeurosis layers extending up to the tensor fasciae latae muscle via the iliotibial tract. The anterior limit is formed by the posterior border of the femoral neck and the greater and lesser trochanters (Table I). Within the space, superior to inferior, the piriformis, superior gemellus, obturator internus, inferior gemellus and quadratus femoris are included. The medial margin is comprised of the greater and minor sciatic foramina. The greater sciatic foramen is bounded by the outer edge of the sacrum, greater sciatic notch (superior) and sacrospinous ligament (inferior). The limits of the lesser sciatic foramen are the lesser sciatic notch (external), sacrospinous lower border (superior) and the upper edge of the sacrotuberous ligament (inferior) 1–3 (Table I).

Table I.

Limits and contents of the deep gluteal space.

Limits

|

Content

|

The piriformis muscle occupies a central position in the buttock and is an important reference for identifying the neurovascular structures emerging above and below it (Figure 1). This muscle arises from the ventrolateral surface of the S2–S4 sacral vertebrae, gluteal surface of the ileum, and sacroiliac joint capsule. It runs laterally through the greater sciatic foramen, becomes tendinous, and inserts to the piriformis fossa at the medial aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur often partially blended with the common tendon of obturator/gemelli complex. Distal to the piriformis muscle is the cluster of short external rotators: the gemellus superior, obturator internus, gemellus inferior, and quadratus femoris muscle4,5. The branches of the L5, S1, and S2 spinal nerves innervate the piriformis muscle. There are six possible anatomical relationships between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle6,7: (a) Sciatic nerve passes below the piriformis muscle; (b) Divided nerve passes through and below the muscle; (c) A divided nerve passes above and below the muscle; (d) Undivided nerve passes through the piriformis (e) Divided nerve passes through and above the muscle or (f) Smaller accessory piriformis with its own separate tendon and sciatic nerve passes through the piriformis (Figure 2). In 120 cadaver dissections, Beason and Anson6 found that the most common arrangement was the undivided nerve passing below the piriformis muscle (84%) followed by the divisions of the sciatic nerve between and below the muscle (12%). In 130 anatomic dissections, Pecina7 found that the undivided nerve passed below the muscle in 78% of his dissections and the divided nerve passed through and below the muscle in 21%. He noted the relation between high-level divisions of the sciatic nerve (i.e., in the pelvis) and the common peroneal nerve passing through the piriformis muscle.

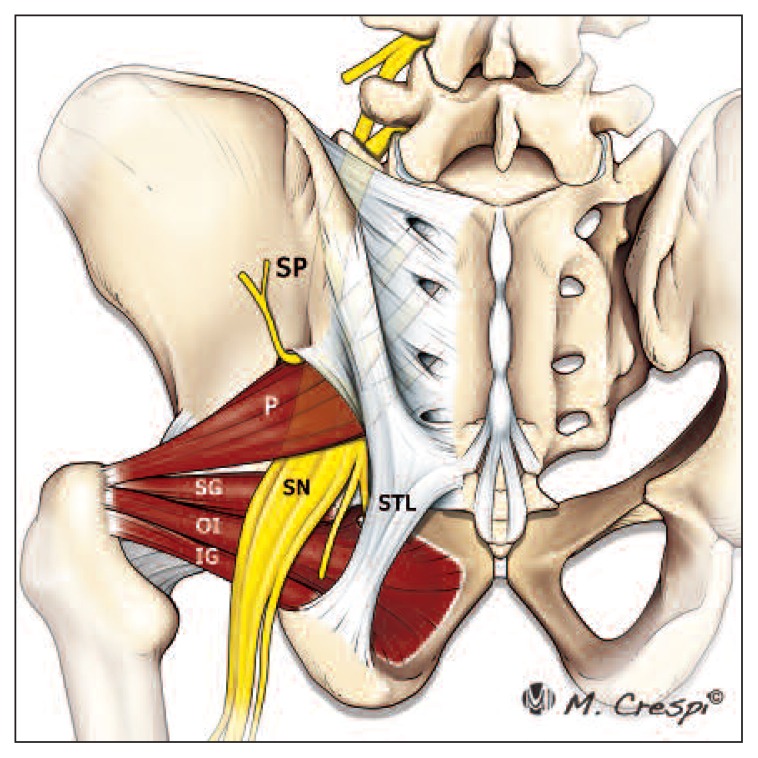

Figure 1.

Normal anatomy of the subgluteal space. The diagram illustrates the main bone, ligament, muscle and tendon structures located in subgluteal space in a back view. SP sacral plexus, SN sciatic nerve, STL sacrotuberous ligament, P piriformis muscle, SG superior gemellus muscle, OI obturator internus muscle, IG inferior gemellus muscle (Reprint with permission from19).

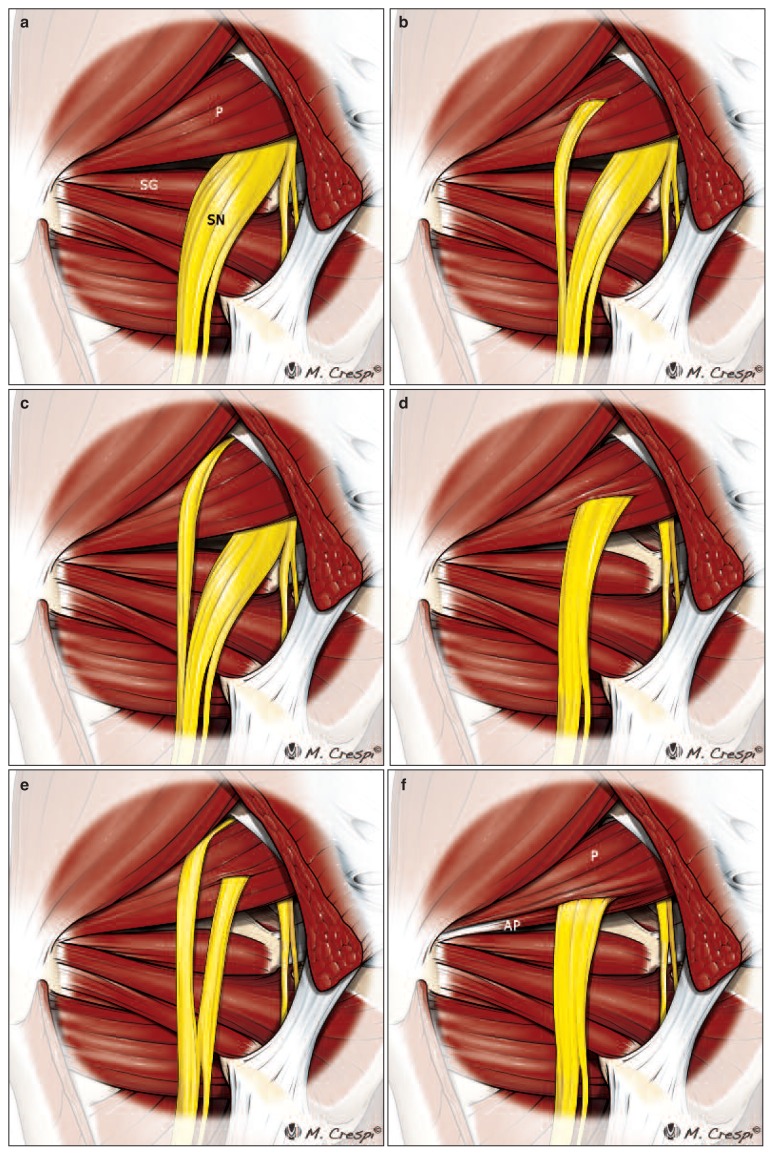

Figure 2.

a–f. Anatomic variations of the relationship between the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve. Diagrams illustrate the six variants, originally described by Beaton and Anson. (a) An undivided nerve comes out below the piriformis muscle (normal course). (b) A divided sciatic nerve passing through and below the piriformis muscle. (c) A divided nerve passing above and below an undivided muscle. (d) An undivided sciatic nerve passing through the piriformis muscle. (e) A divided nerve passing through and above the muscle heads. (f) Diagram showing an unreported additional B-type variation consisting of a smaller accessory piriformis (AP) with its own separate tendon. SN sciatic nerve, P piriformis muscle, SG superior gemellus muscle (Reprint with permission from19).

Function: the piriformis muscle potentially plays a role not only in external rotation of the hip but also in restricting posterior translation of the femoral head when the joint is flexed due to the shift towards a more posterior position of this muscle with respect to the hip joint in hip flexion8. Hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation stretch the piriformis muscle and cause narrowing of the space between the inferior border of the piriformis, superior gemellus and sacrotuberous ligament.

Seven neural structures exit the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch (Table II)9. Accompanying the respective nerves are the superior gluteal vessels, inferior gluteal vessels, and internal pudendal vessels. It is important to differentiate normal neurovascular bundles and isolated nerves that normally run along the subgluteal space and not to confuse them with fibrovascular bands. After leaving the piriformis muscle, the sciatic nerve runs posteriorly to the obturator/gemelli complex and quadratus femoris muscle. It passes between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter lying close to the posterior capsule of the hip. Miller et al.10 performed a cadaveric study and concluded that the sciatic nerve is located at a mean distance of 1.2±0.2 cm from the most lateral aspect of the ischial tuberosity, and it has an intimate relation with proximal origin of the hamstrings like the inferior gluteal nerve and artery. As it runs down, the nerve describes a wide curve cephalad to the ischial tuberosity. On reaching the lateral aspect of this prominence, the sciatic nerve changes direction to run almost vertically down toward the thigh. The sciatic nerve has a segmental arterial supply by branches of the inferior gluteal artery, medial circunflex femoral artery, and perforating arteries of the thigh (usually the first and second)11–13 and the venous drainage is performed through the perforators to the femoral profunda system in the thigh and to the popliteal vein at the knee14. Under normal conditions, the sciatic nerve is able to stretch and glide in order to accommodate moderate strain or compression associated with joint movement. During a straight leg raise with knee extension, the sciatic nerve experiences a proximal excursion of 28.0 mm at 70–80° of hip flexion15.

Table II.

Neural structures exit the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch.

|

Deep Gluteal Syndrome

Deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) is an under-diagnosed entity characterized by pain and/or dysesthesias in the buttock area, hip or posterior thigh and/or radicular pain due to a non-discogenic sciatic nerve entrapment in the subgluteal space. To date, reports including the term “deep gluteal syndrome” (DGS) in orthopedic and radiologic journals have been limited. However, many articles discuss or focus on piriformis syndrome. Currently, there are many known causes of sciatic nerve entrapment that have nothing to do with piriformis syndrome, which is actually a subtype of DGS. In clinical practice, in addition, causes of sciatic nerve entrapment are often overlooked because of the high sensitivity of lumbar spine magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. It is known that extraspinal sacral plexus and sciatic nerve entrapments may result from a wide variety of extrapelvic (within the subgluteal space) or intrapelvic pathologies16.

Clinical examination and symptoms

Clinical assessment of patients with DGS is difficult since the symptoms are imprecise and may be confused with other lumbar and intra - or extraarticular hip diseases. It is usually characterized by a set of symptoms and semiological data occurring in isolation or in combination1,2,17. The most common symptoms include hip or buttock pain and tenderness in the gluteal and retro-trochanteric region and sciatica-like pain, often unilateral but sometimes bilateral, exacerbated with rotation of the hip in flexion and knee extension. Intolerance of sitting more than 20 to 30 min, limping, disturbed or loss of sensation in the affected extremity, lumbago and pain at night getting better during the day are other symptoms reported by patients1,2,17. An antalgic position is frequently found. Physical examination tests have been used for the clinical diagnosis of sciatic nerve entrapment including the Lasègue test, Pace’s sign, Freiberg’s sign, Beatty test, FAIR test and active and seated piriformis stretch test2,17. The seated piriformis stretch test is a flexion/adduction with internal rotation test performed with the patient in the seated position. The examiner extends the knee and passively moves the flexed hip into adduction with internal rotation while palpating 1 cm lateral to the ischium (middle finger) and proximally at the sciatic notch (index finger). A positive test is the re-creation of the posterior pain. The active piriformis test is performed by the patient pushing the heel down into the table, abducting and externally rotating the leg against resistance, while the examiner monitors the piriformis for pain. The active piriformis and seated piriformis stretch tests reveal higher sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of sciatic nerve entrapments than the other tests, especially when both are used in combination17.

Etiology

Multiple orthopedic and non-orthopedic conditions may manifest as a DGS2,16,18. Specific entrapments within the subgluteal space include fibrous bands, piriformis syndrome, obturator internus/gemellus syndrome, quadratus femoris and ischiofemoral pathology, hamstring conditions, gluteal disorders or orthopedic causes.

1. Fibrous and fibrovascular bands

The concept of fibrous bands, which may or not contain blood vessels, playing a role in causing symptoms related to sciatic nerve entrapment represents a radical change in the current diagnosis and therapeutic approach for the all-inclusively used term “piriformis syndrome”19. Typically constricting fibrous bands are present in many cases of sciatic nerve entrapment during endoscopy1,2. Under normal conditions, the sciatic nerve is able to stretch and glide in order to accommodate moderate strain or compression associated with joint movement20. Diminished or absent sciatic mobility during hip and knee movements due to these bands is the precipitating cause of sciatic neuropathy (ischemic neuropathy)17 (Figure 3). From the point of view of its macroscopic structure, there are three primary types of bands: fibrovascular bands, with vessels macroscopically identifiable by MRN imaging and endoscopy, pure fibrous bands, without identifiable macroscopic vessels, and pure vascular bands, exclusively formed by a vessel without surrounding fibrous tissue19. Based on their location, they can be classified as proximal, which affect the sciatic nerve in the vicinity of the greater sciatic notch, distal, which affect it in the ischial tunnel region between the quadratus femoris and proximal insertion of the hamstrings, and middle bands, located at the level of the piriformis and obturator internus-gemelli complex. In each of these three locations, these bands can be located medial or lateral to the sciatic nerve. Depending on the pathogenic mechanism, bands can be classified as (Figure 4):

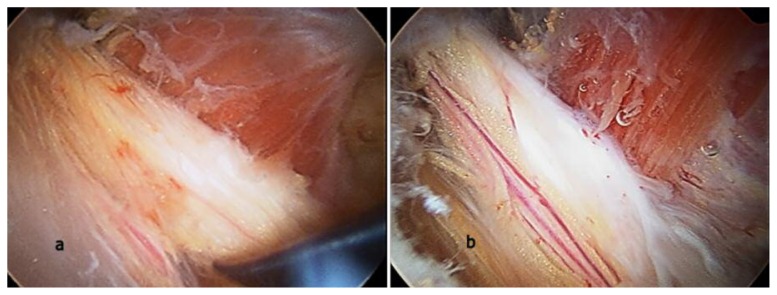

Figure 3 a, b.

Endoscopic view showing the pathogenic mechanism of DGS. (a) Edematous and flattened sciatic nerve due to fibrovascular entrapment in a patient with ischemic neuritis. (b) Normal vascularization recovery after nerve neurolysis (Reprint with permission from19).

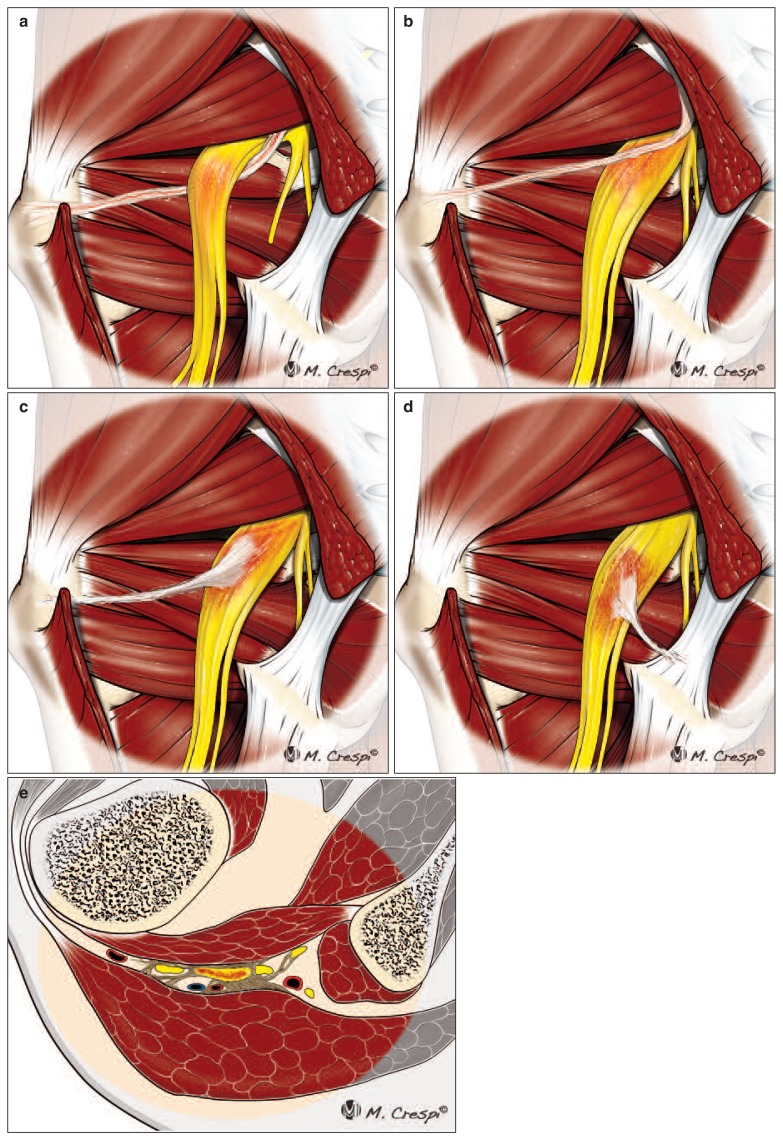

Figure 4 a–e.

Pathogenic classification of fibrous/fibrovascular bands. (a, b) Compressive or bridge-type bands limiting the movement of the sciatic nerve from anterior to posterior (type 1A) or from posterior to anterior (type 1B). (c, d) Adhesive or horse-strap bands (type 2), which bind strongly to the sciatic nerve structure, anchoring it in a single direction. They can be attached to the sciatic nerve laterally (type 2A) or medially (type 2B). (e) Bands anchored to the sciatic nerve with undefined distribution (type 3) (Reprint with permission from19).

Compressive or bridge-type bands (type 1), which limit the movement compressing the nerve from anterior to posterior (type 1A) or from posterior to anterior (type 1B). The former is located in front of the sciatic nerve. These fibrous bands usually extend from the posterior border of the greater trochanter and surrounding soft tissues (distal insertions are variable) to the gluteus maximus onto the sciatic nerve and extend up to the greater sciatic notch.

Adhesive bands or horse-strap bands (type 2) which bind strongly to the sciatic nerve structure, anchoring it in a single direction and not allowing it to perform its normal excursion during hip movements. These bands can be attached to the sciatic nerve laterally from the major trochanter (type 2A) or medially from the sacrotuberous ligament (type 2B). Lateral bands are the most common. Among those classified as medial bands, a proximal location is more frequent.

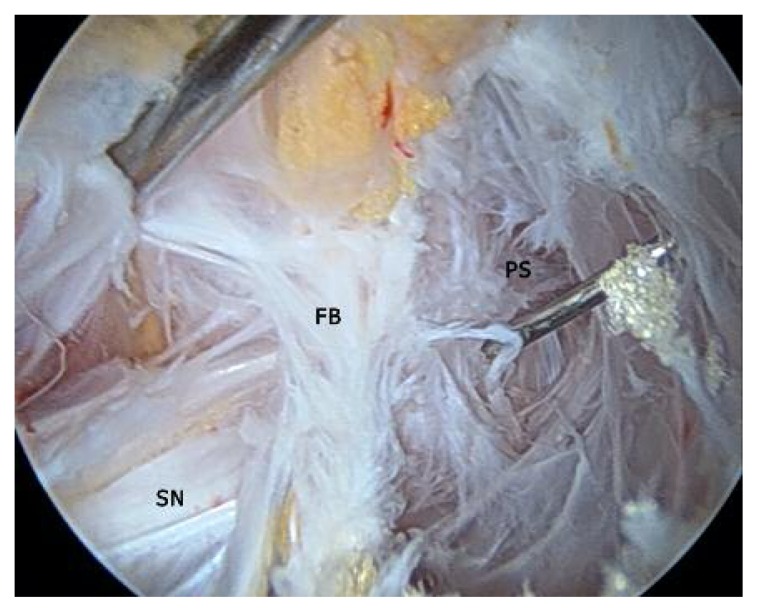

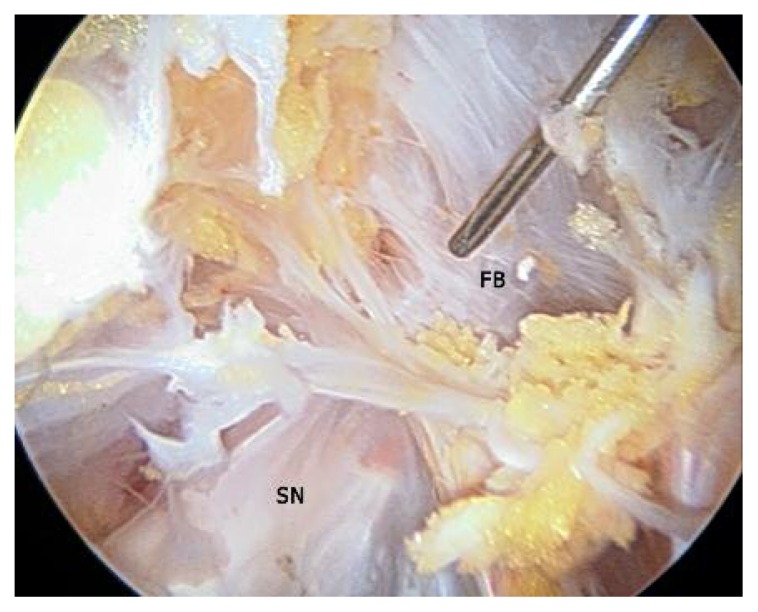

Bands anchored to the sciatic nerve with undefined distribution (type 3). These kinds of bands with an erratic distribution are characterized by anchoring the nerve in multiple directions 19 (Figure 5,6).

Figure 5.

Left hip. Endoscopic view of type-3 scarred bands in a 51-year-old female with DGS. SN Sciatic nerve, PS Piriformis scar, FB Fibrous bands.

Figure 6.

Left hip. The endoscopic image shows the sciatic nerve decompression, more complex when this type of bands are resected. SN Sciatic nerve, FB Fibrous bands with undefined distribution (Type 3).

2. Piriformis syndrome

Piriformis syndrome can be classified as a subgroup of DGS but not all DGSs are piriformis syndrome. The potential sources of pathology related to the piriformis muscle include:

Hypertrophy of the piriformis muscle. Asymmetrically enlarged piriformis muscle with anterior displacement of the sciatic nerve may be a cause of DGS. Asymmetry associated with sciatic nerve hyperintensity at the sciatic notch revealed a specificity of 93% and sensitivity of 64% in patients with piriformis syndrome distinct from that which had no similar symptoms20.

Dynamic sciatic nerve entrapment by the piriformis muscle. Dynamic entrapment of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis is not uncommon1. Often the only finding at imaging that can be shown is nerve signal hyperintensity in edema-sensitive sequences. The definitive diagnosis is endoscopic, demonstrating the entrapment during dynamic maneuvers.

Anomalous course of the sciatic nerve (anatomical variations).

Descriptions of variations concerning the relationship between the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve have been limited6,21–23. Six categories of anatomic variations of the relationship between the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve were originally reported in 1938 by Beaton and Anson6. Smoll presented the overall reported incidence of these six variations in over 6,000 dissected limbs. Relationships A, B, C, D, E and F occurred in 83.1, 13.7, 1.3, 0.5, 0.08 and 0.08% of limbs, respectively22. Therefore, with the exception of relationship A (normal course), the B-type piriformis-sciatic variation is the most commonly found. The anomaly itself may not always be the etiology of DGS symptoms as some asymptomatic patients present these variations and some symptomatic patients do not. A subsequent event such as any etiology reported in this article or prolonged sitting, direct trauma to the gluteal region, prolonged stretching, overuse, pelvic/spinal instability or orthopedic conditions may then precipitate sciatic nerve neuropathy.

3. Gemelli-obturator internus syndrome

Obturator internus/gemelli complex pathology is rare. Because of its proximity and similarity in both structure and function, most treatments for piriformis syndrome also affect the internal obturator24. Dynamic compression of the sciatic nerve caused by a stretched or altered dynamic of the obturator internus muscle should be included as a possible diagnosis for DGS25. As the sciatic nerve passes under the belly of the piriformis and over the superior gemelli/obturator internus, a scissor-like effect between the two muscles can be the source of entrapment26.

4. Quadratus femoris and ischiofemoral pathology

Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome (IFI) is an underrecognized form of atypical, extra-articular hip impingement defined by hip pain related to narrowing of the space between the ischial tuberosity and the femur. Narrowing of the ischiofemoral space leads to muscular, tendon and neural changes27,28. Characteristic findings are a decreased ischiofemoral space compared to healthy controls (the ischiofemoral space measures 23±8 mm and femoral space 12±4 mm) and altered signals from the quadratus femoris muscle, which results in edema, muscular rupture or atrophy27,28. The syndrome may occur acutely because of inflammation/edema or chronically because of fibrous tissue formation that traps the sciatic nerve. The clinical assessment of patients with IFI is difficult because the symptoms are imprecise and may be confused with other lumbar and intra or extraarticular hip diseases, including deep gluteal syndrome19. Patients typically present with mild to moderate nonspecific chronic and sometimes gradually increased pain in the deep gluteal region. This pain can be also located lateral to the ischium, in the groin and/or in the center of the buttock. Limited sitting time and limitation of physical activities including long-stride walking are frequent. Duration of these symptoms vary between months and several years and usually there is no a precipitating injury (except trauma-related cases) 27,29,31. The specific physical examination test included the long-stride walking test and IFI test1,19,29. The injection test of the ischiofemoral space (IFS) has both a diagnostic and therapeutic function. Endoscopic decompression of the IFS appears useful in improving function and diminishing hip pain in patients with IFI but conservative treatment is always the first step in the treatment algorithm32.

5. Hamstring conditions

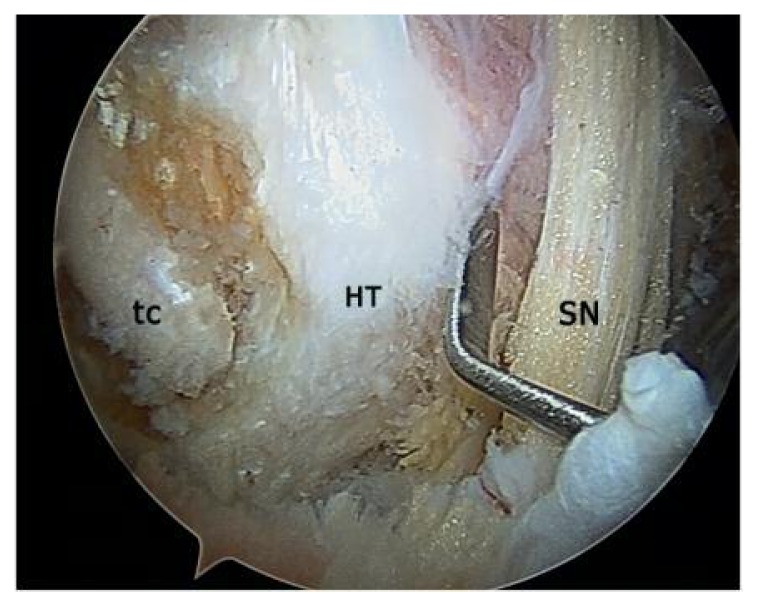

The sciatic nerve can be affected by a wide spectrum of hamstring origin enthesopathies appearing either isolated or in combination: partial/complete hamstring strain (acute, recurrent or chronic), tendon detachment avulsion fractures (acute or chronic/nonunited), apophysitis, nonunited apophysis, proximal tendinopathy, calcifying tendinosis (Figure 7) and contusions result in entrapment during hip motion (ischial tunnel syndrome)33. In the acute phase, edema predominates as a characteristic imaging finding resulting in sciatic nerve irritation. Chronic inflammatory changes and adhesions causing scar tissue between tendons or muscles and sciatic nerve result in entrapment during hip motion.

Figure 7.

Right hip: Endoscopic image shows a severe degenerative calcifying tendinopathy of hamstring tendons with reactive sciatic neuritis. tc Calcifying tendinopathy, HT Hamstring tendons, SN Sciatic nerve.

Deep Gluteal Syndrome Treatment

First-line treatment consists of conservative measures, including rest, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants and physical therapy for a 6-weeks period. The infiltration test around the tendon with lidocaine is valid for diagnosis and treatment. In refractory cases, botox infiltration imaging ultrasound guided is the next step. Botulinic toxin blocks presynaptic conduction, thereby creating a temporary paresis, and induces a denervative process and atrophy of the piriformis muscle. Endoscopic decompression of the deep gluteal space appears useful in improving function and diminishing hip pain in patients with DGS although conservative treatment is always the first step in the treatment algorithm.

Surgical technique and normal endoscopic anatomy of the subgluteal space. Deep gluteal space access

The subgluteal space is a recently defined anatomic region for endoscopic access1. Careful preoperative planning, precise portal placement, a knowledge of the anatomy and potential complications, and a methodical sequence of endoscopic examination, are essential for effective arthroscopy/endoscopy of any joint or space34. The deep gluteal space is the posterior extension of the peritrochanteric space so entrance into the subgluteal space is accomplished by portals traveling through the peritrochanteric space, which is between the greater trochanter and the iliotibial band. In most cases, the procedure is performed in the supine position and may be performed concomitant to a hip arthroscopy of the central and/or peripheral compartments, if indicated.

Voos et al.35 described the arthroscopic anatomy of the hip in the peritrochanteric compartment: the borders of the peritrochanteric compartment consist of the tensor fascia lata and iliotibial band laterally, the abductor tendons superomedially, the vastus lateralis inferomedially, the gluteus maximus muscle superiorly, and its tendon posteriorly. Within the space exist the trochanteric bursae and the gluteus medius and minimus tendons at their attachment on the greater trochanter.

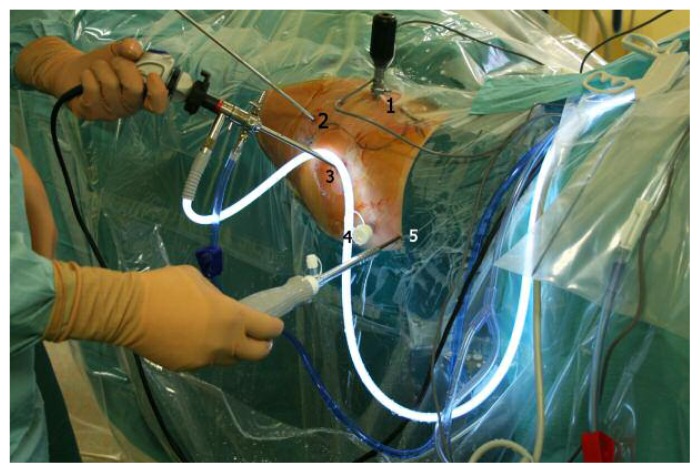

Different portals have been described to access the peritrochanteric space. Basically, we can divide these portals into two groups: (1) standard portals redirected to the peritrochanteric space (anterolateral, anterior, and posterolateral portals) and (2) portals described to access the peritrochanteric space36 (proximal anterolateral accessory portal, distal anterolateral accessory portal, peritrochanteric space portal, and auxiliary posterolateral portal). The peritrochanteric space portal is established at the level of the modified mid-anterior portal 1 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine and in the interval between the tensor fascia lata (laterally) and the sartorius (medially). This portal enters peritrochanteric space underneath IT band at level of vastus lateralis ridge (Figure 8). Entering at vastus lateralis ridge avoids inadvertent deep penetration of vastus lateralis or gluteus medius muscle. The proximal anterolateral accessory portal is placed directly posterior to the proximal mid-anterior portal 3–4 cm proximal. It perforates the junction of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata to form the iliotibial band, entering into the peritrochanteric space. The distal anterolateral accessory portal is placed distally to the peritrochanteric space portal at the same distance that exists between the first two portals (proximal anterolateral accessory and peritrochanteric space portals). It penetrates into the peritrochanteric space just anterior to the iliotibial band (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Right hip. Entering at vastus lateralis ridge avoids inadvertent deep penetration of vastus lateralis or gluteus medius muscle.

Figure 9.

Left gluteal region showing portal placement for subgluteal endoscopy. (1) Midanterior portal (2) Distal anterolateral accessory portal (3) Anterolateral portal (4) Posterolateral portal (5) Auxiliary posterolateral portal placement.

Surgical technique

Following the completion of the central and peripheral work, any traction is discontinued, and the leg is abducted to about 15–20° in order to open the interval between the trochanter and the iliotibial band and the leg is internally rotated 20–40°, for the same reason. We performe the procedure with the 70° arthroscope, and in some cases or larger patients the use of a extralonger arthroscope is require. First the peritrochanteric space portal is established. A 5.0 mm metallic cannula is positioned between the ITB and the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter, and the tip of the cannula can be used to sweep proximal and distal to ensure placement in the proper location. Fluoroscopy can also be used to confirm that the cannula is located immediately adjacent to the greater trochanter at the vastus ridge. The arthroscope is place perpendicular to the patient and look in a distal direction in order to identify the gluteus maximus tendon inserting into the linea aspera of the femur posteriorly. Then the peritrochanteric space is entered through the anterolateral accessory, distal anterolateral accessory and posterolateral portals as working portals, and systematic inspection of this space is performed. Visualizing through the peritrochanteric portal, the examination begins at the gluteus maximus insertion at the linea aspera (Figure 10). Fibrous tissue bands may need to be removed from the space in this location to visualize the coalescence. Once this structure is identified, the area of the sciatic nerve can then be known. It lies directly posterior to this structure as it exits the subgluteal space. Rotating proximally, the vastus lateralis fibers are identified and can be traced toward its insertion on the vastus tubercle. Rotating the arthroscope anterior and superior, the gluteus minimus tendon is visualized anteriorly. Moving anteriorly above the gluteus minimus lies the gluteus medius tendon and its attachment to the greater trochanter. Fibrous bands from the trochanteric bursa may need to be removed in order to best visualize the medius attachment to the greater trochanter. The ileotibial band sits posteriorly and can be seen with a small posterior maneuver of the arthroscope and rotation. For better sciatic nerve assessment we switch the scope to the anterolateral portal and the procedure then continues by exposure of the bursa and resection of abnormal bursal tissue, and the sciatic nerve is identified. It lies 3–6 cm directly posterior to gluteus maximus tendon inserting into the linea aspera as it exits the subgluteal space. Sciatic nerve assessment is carry out through the anterolateral and posterolateral portals in many cases, but sometimes we need and auxiliary posterolateral portal1. It is placed 3 cm posterior and 3 cm superior to the greater trochanter. It allows a better visualization of the sciatic nerve up to the sciatic notch. Inspection of the sciatic nerve begins distal to the quadratus femoris, just above the gluteal sling. Visualize the sciatic nerve as it courses posterior to the quadratus femoris, noting the color, epineural blood flow, and epineural fat. A normal sciatic nerve will have noticeable epineural blood flow and epineural fat, whereas an abnormal sciatic nerve will appear white, lacking epineural blood flow (Figure 11). The epineural fat in many cases is diminished or completely obliterated. Take care to preserve as much of the epineural fat pad as possible during dissection37. A blunt probe or surgical dissector can then be employed to expose the sciatic nerve and determine the tension38. After the dissection at the level of the quadratus femoris, turn the scope distal and perform all distal decompression before any proximal work. Inspect the ischial tunnel hamstring origin, and sacrotuberous ligament, releasing any fibers from the sciatic nerve. Assess the lateral, medial, and retrosciatic borders of the sciatic nerve to ensure the distal release is complete. Identify the posterior cutaneous nerve. After the distal dissection, move proximal for a trochanteric bursectomy, while paying attention to keep the shaver blade directed away from the gluteus medius. The sciatic nerve should now also be possible to visualise proximally and care must be taken to avoid nerve damage caused by the motorised instrument or excessive traction. When the piriformis tendon is identified, it should be possible to identify the tendons of the gemellus and obturatorius internus muscles. Clean any vascular scar bands over the quadratus femoris and the conjoint tendon of the gemelli and obturator internus. A blunt dissector, such as a switching stick, can be employed for release of scar bands. Fibrovascular tissue can also be cauterized with a radiofrequency probe. The concept of fibrous bands playing a role in causing symptoms related to sciatic nerve mobility and entrapment represents a radical change in the current diagnosis of and therapeutic approach to DGS19. With the arthroscope visualizing the nerve, the hip can be flexed and rotated in any direction in order to assess not only the mobility but also for any evident of impingement. The kinematic excursion of the sciatic nerve is then assessed with the leg in flexion with internal/external rotation and full extension with internal/external rotation1. Finally, the piriformis muscle is located, and any abnormal anatomical variants are identified. Constant attention must be paid to the branches of the inferior gluteal artery lying in proximity to the piriformis muscle. Looking back proximal, in the region of the obturator internus a superficial arterial branch of the inferior gluteal artery crosses the sciatic nerve laterally between the piriformis and superior gemellus muscles and must be be cauterized and released prior to inspection of the piriformis with a radiofrequency probe. Some cases involve a large vessel or a confluence of vessels which may require ligation. The piriformis muscle can be classified as: split, bulging split with the sciatic nerve passing through the body, split tendon with an anterior and posterior component, split in 2 distinct components with one dorsally and one inferiorly going between a bifurcated sciatic nerve1. In many cases, a thick tendon can hide under the belly of the piriformis overlying the nerve. A rotatory shaver can be used to shave the distal border of the piriformis muscle to gain adequate access to the piriformis tendon. Carefully grasp the tendon with arthroscopic scissors and pull the scissors toward you to ensure only the tendon is released (Figure 12). The superior gluteal nerve and artery are in proximity and must be diligently avoided. Identify the inferior gluteal nerve after its pass inferior to the piriform muscle and possible anatomical variations of the sciatic nerve. Check obturator internus for anatomical variations and release if you consider there is compression of the sciatic nerve (Figure 13). Finally probe the sciatic nerve up to the sciatic notch (Figure 14).

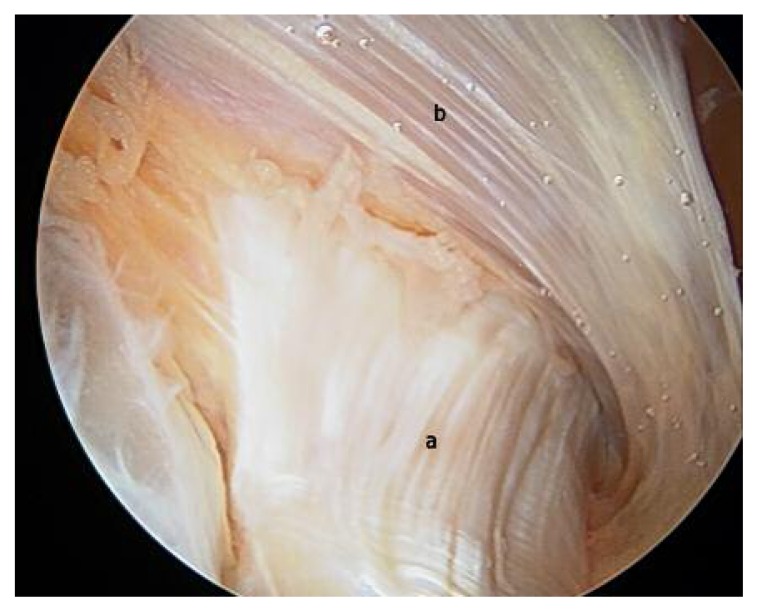

Figure 10.

Endoscopic view right hip. Visualizing through the peritrochanteric portal, the examination begins at the gluteus maximus insertion at the linea aspera. (a) Gluteus maximus insertion; (b) Vastus lateralis.

Figure 11.

Left hip. Normal sciatic nerve with noticeable epineural blood flow.

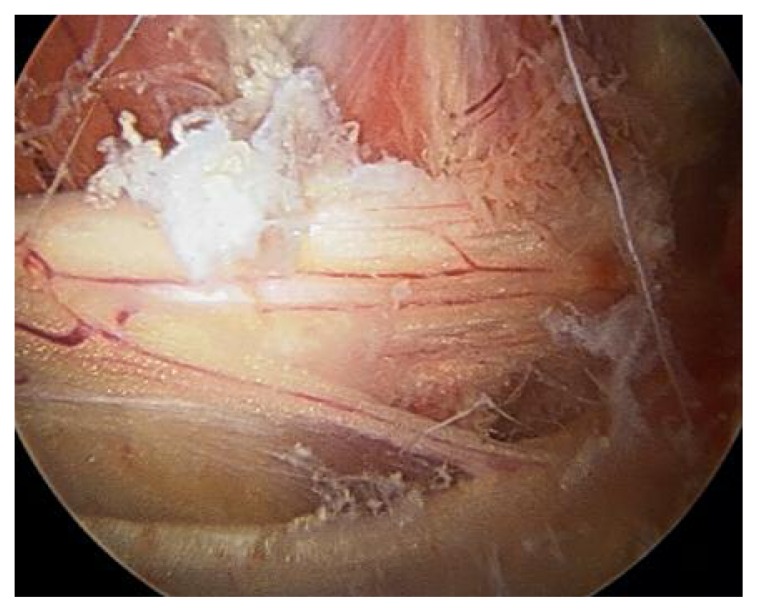

Figure 12.

Left hip. Sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch. a) Piriformis tendon after release; b) fibrovascular band, SG Superior gemellus muscle, SN Sciatic nerve.

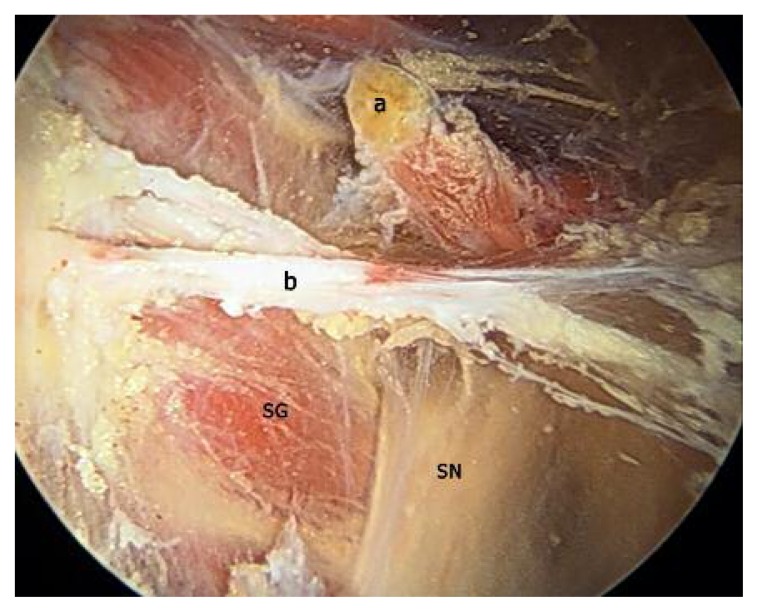

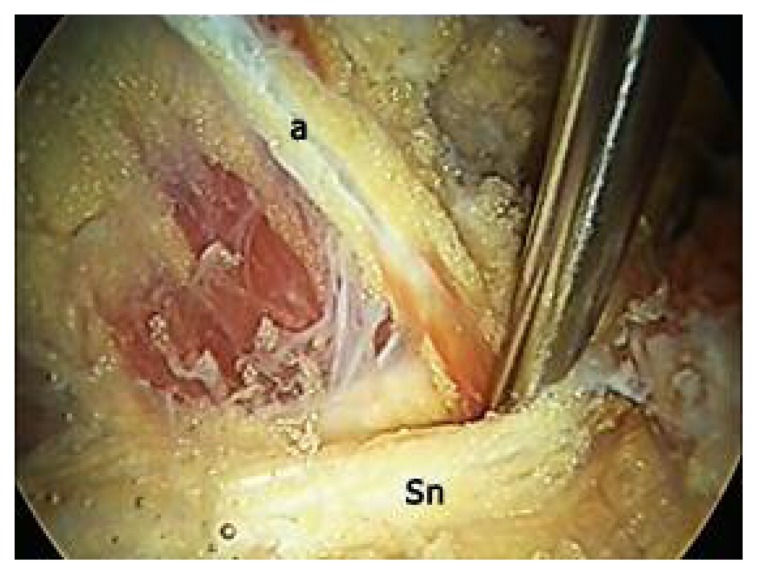

Figure 13.

Left hip. Endoscopic view of obturator splitting the sciatic nerve.

Figure 14.

Fluoroscopic view showing location of the scope and instruments in the subgluteal space. Radiofrequency probe at the sciatic notch.

Isquiofemoral impingement: Endoscopic Technique

Arthroscopic access to decompress the IFS, as an alternative to an open approach, has been recently described with high success rates. The posterolateral trans-quadratus approach seems to be the most appropriate route29. Patient is positioned supine on a traction table (without applying traction), in 20° of contralateral tilt and with the affected limb in internal rotation. A 70° high definition long arthroscope is utilized. The deep gluteal space is endoscopically access using 3 portals: anterolateral, posterolateral, and auxiliary distal at the level of the lesser trochanter [ischiofemoral impingement (IFI) portal]. The anterolateral portal is used for access to obtain visualization. The posterolateral portal and auxiliary distal portal are use for the introduction of a probe, arthroscopic burr, curved retractors, or the arthroscope. The main surgical steps are: peritrochanteric inspection and bursectomy; identification of quadratus femoris muscle and sciatic nerve and palpation of the lesser trochanter with a blunt probe under fluoroscopic control. Access to the lesser trochanter is achieved via a small window in the quadratus femoris muscle between the medial circumflex femoral artery (proximal) and first perforating femoral artery (distal). Osteoplasty of the posterior 1/3 of the lesser trochanter is then carried out (Figure 15), aiming for an ischiofemoral space of at least 17 mm and leaving non-impingement bone and most of iliopsoas insertion intact (Figure 16). Confirm ischiofemoral space decompression with intraoperative endoscopy and fluoroscopy. If hamstring repair is necessary, partial tearing debridement with an oscillating shaver and suture (one suture anchor per centimeter of detachment) is required.

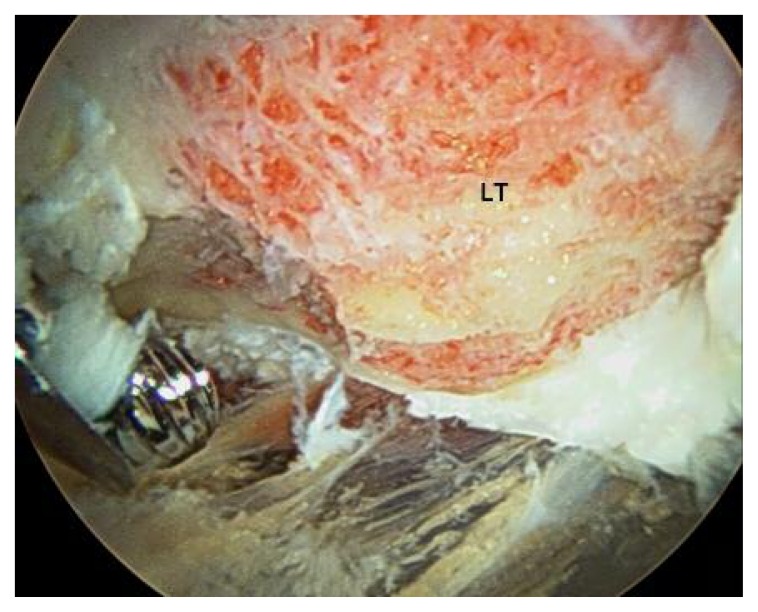

Figure 15.

Left hip. Intraoperative endoscopic image showing resection of the lesser trochanter with a 5.5 mm burr. LT Lesser trochanter.

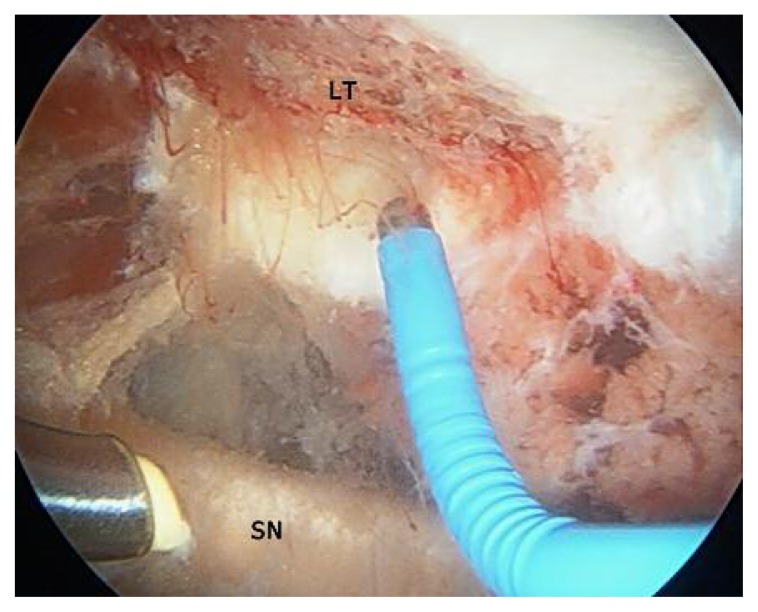

Figure 16.

Left hip. Transquadratus endoscopic treatment of isquiofemoral impingement. The aim of the osteoplasty of the posterior one third of the lesser trochanter is to obtain an isquiofemoral space of at least 17 mm leaving non-impingement bone and the iliopsoas insertion intact. Radiofrecuency probe measuring the distance. SN Sciatic nerve LT Lesser trochanter after osteoplasty.

In 2003, Dezawa et al.39 reported the endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve entrapment as an effective and minimally invasive approach on six cases of piriformis syndrome. Martin et al.1 reported a case series of 35 patients presenting with deep gluteal syndrome treated endoscopically. Average duration of symptoms was 3.7 years with an average pre-operative verbal analog score of 7, which decreased to 2.4 post-operatively. Pre-operative modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS) was 54.4 and increased to 78 post-operatively. Twenty-one patients reported preoperative use of narcotics for pain; 2 remained on narcotics post-operatively (unrelated to initial complaint). Eighty three percent of patients had no post-operative sciatic sit pain (inability to sit for >30 min). Five patients experienced low mHHS scores and modest pain relief post-operatively. This poor outcome group may be related to femoral retroversion and previous abdominal surgery. Perez-Carro et al.40 reported 26 cases of endoscopic sciatic decompression with a mean follow-up of 11 months. Nineteen cases presented excellent or good results. The mHHS went from 56 pre- to 79 post-operative on average. For this chapter we have reviewed and evaluated the results and endoscopic findings of 52 patients (52 hips) treated in our clinic for deep gluteal syndrome and endoscopic sciatic nerve release in the subgluteal space between November 2011 to April 2015 (Tables II, III). Thirty-nine patients reported good to excellent outcomes. The mHHS went from 52 pre-operative to 79 post-operative on average. 13 patients reported to be better but not good and required continued narcotic use after surgery (Tables III, IV).

Table III.

Patients treated for endoscopic sciatic nerve release. November 2011 to April 2015.

|

Table IV.

Surgical Technique.

|

Conclusion

DGS is an underrecognized condition. Its etiology is multifactorial. Two common and underdiagnosed causes are fibrovascular bands and entrapment related to the external rotator muscles. The development of periarticular hip endoscopy has led to an understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying piriformis syndrome, which has supported its further classification. The whole sciatic nerve trajectory in the deep gluteal space can be addressed by an endoscopic surgical technique, allowing the treatment of the diverse causes of sciatic nerve entrapment. Endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve appears useful in improving function and diminishing hip pain in sciatic nerve entrapments within the subgluteal space. The technique of endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve requires significant hip arthroscopy experience with familiarity with the gross and endoscopic anatomy.

The study was conducted according to international the ethical standards41.

References

- 1.Martin HD, Shears SA, Johnson JC, Smathers AM, Palmer IJ. The endoscopic treatment of sciatic nerve entrapment/deep gluteal syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):172–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin HD, Palmer IJ, Hatem MA. Deep gluteal syndrome. In: Nho S, Leunig M, Kelly B, Bedi A, Larson C, editors. Hip arthroscopy and hip joint preservation surgery. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierry G, Simeone FJ, Borg-Stein JP, Clavert P, Palmer WE. Sacrotuberous ligament: relationship to normal, torn, and retracted hamstring tendons on MR images. Radiology. 2014;271(1):162–71. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallin RP. Sciatic pain and the piriformis muscle. Postgrad Med. 1983;74:69–72. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1983.11698378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen WS. Bipartite piriformis muscle: An unusual cause of sciatic nerve entrapment. Pain. 1994;58:269–72. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaton LE, Anson BJ. The relation of the sciatic nerve and its subdivisions to the piriformis muscle. Anat Record. 1937;70:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pecina M. Contribution to the etiological explanation of the piriformis syndrome. Acta Anat. 1979;105:181–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche JJ, Jones CD, Khan RJ, Yates PJ. The surgical anatomy of the piriformis tendon, with particular reference to total hip replacement: a cadaver study. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:764–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B6.30727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Standring S. Grays anatomy the anatomical basis of clinical practice. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SL, Gill J, Webb GR. The proximal origin of the hamstrings and surrounding anatomy encountered during repair. A cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):44–48. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgakis E, Soames R. Arterial supply to the sciatic nerve in the gluteal region. Clin Anat. 2008;21:62–5. doi: 10.1002/ca.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karmanska W, Mikusek J, Karmanski A. Nutrient arteries of the human sciatic nerve. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 1993;52:209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ugrenovic SZ, Jovanovic ID, Vasovic LP, Stefanovic BD. Extraneural arterial blood vessels of human fetal sciatic nerve. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;186:147–53. doi: 10.1159/000104407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Pinal F, Taylor GI. The venous drainage of nerves; anatomical study and clinical implications. Br J Plast Surg. 1990;43:511–20. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(90)90113-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coppieters MW, Alshami AM, Babri AS, Souvlis T, Kippers V, Hodges PW. Strain and excursion of the sciatic, tibial, and plantar nerves during a modified straight leg raising test. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1883–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulcu DG, Naderi S. Differential diagnosis of intraspinal and extraspinal non-discogenic sciatica. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(11):1246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin HD, Kivlan BR, Palmer IJ, Martin RL. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for sciatic nerve entrapment in the gluteal region. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):882–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ergun T, Lakadamyali H. CT and MRI in the evaluation of extraspinal sciatica. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(993):791–803. doi: 10.1259/bjr/76002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Pérez-Carro L, Abascal F, Canga A. Deep gluteal syndrome: anatomy, imaging, and management of sciatic nerve entrapments in the subgluteal space. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(7):919–34. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis AM, Layzer R, Engstrom JW, Barbaro NM, Chin CT. Magnetic resonance neurography in extraspinal sciatica. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1469–72. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Güvençer M, Akyer P, Iyem C, Tetik S, Naderi S. Anatomic considerations and the relationship between the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30(6):467–74. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smoll NR. Variations of the piriformis and sciatic nerve with clinical consequence: a review. Clin Anat. 2010;23(1):8–17. doi: 10.1002/ca.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natsis K, Totlis T, Konstantinidis GA, Paraskevas G, Piagkou M, Koebke J. Anatomical variations between the sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle: a contribution to surgical anatomy in piriformis syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(3):273–80. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filler AG, Gilmer-Hill H. Piriformis syndrome, obturator internus syndrome, pudendal nerve entrapment, and other pelvic entrapments. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans neurological surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009. pp. 2447–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murata Y, Ogata S, Ikeda Y, Yamagata M. An unusual cause of sciatic pain as a result of the dynamic motion of the obturator internus muscle. Spine J. 2009;9(6):e16–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meknas K, Kartus J, Letto JI, Christensen A, Johansen O. Surgical release of the internal obturator tendon for the treatment of retro- trochanteric pain syndrome: a prospective randomized study, with long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(10):124–56. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taneja AK, Bredella MA, Torriani M. Ischiofemoral impingement. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2013;21(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torriani M, Souto SC, Thomas BJ, Ouellette H, Bredella MA. Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome: an entity with hip pain and abnormalities of the quadratus femoris muscle. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(1):186–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatem MA, Palmer IJ, Martin HD. Diagnosis and 2-year outcomes of endoscopic treatment for ischiofemoral impingement. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford GH, Villar RN. Ischiofemoral impingement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(10):1300–2. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B10.26714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayat Z, Konan S, Pollock R. Ischiofemoral impingement resulting from a chronic avulsion injury of the hamstrings. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204017. pii: bcr2014204017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Pérez Carro L, Canga A, Prada R. Evaluation and management of ischiofemoral impingement: a pathophysiologic, radiologic, and therapeutic approach to a complex diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2354-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00256-016-2354-2. On Line March 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bucknor MD, Steinbach LS, Saloner D, Chin CT. Magnetic resonance neurography evaluation of chronic extraspinal sciatica after remote proximal hamstring injury: a preliminary retrospective analy-sis. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(2):408–14. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.JNS13940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez Carro L, Golano P, Fernandez EN, Ruperez VM, Victor Diego V, Cerezal L. Normal articular anatomy. In: Kim J, editor. Hip Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Springer; 2014. pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voos JE, rudzki JR, Shinkdle MK, et al. Arthroscopic anatomy and surgical techniques for peritrochanteric space disorders in the hip. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1246.e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson WJ, Kelly BT. The safe zone for hip arthroscopy: a cadaveric assessment of central, peripheral, and lateral compartment portal placement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1019–26. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin HD, Hatem MA, Champlin K, Palmer IJ. The Endoscopic Treatment of Sciatic Nerve Entrapment/Deep Gluteal Syndrome. Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2012;27:172–83. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guanche CA. Hip Arthroscopy Techniques: Deep Gluteal Space Access. In: Nho SJ, et al., editors. Hip Arthroscopy and Hip Joint Preservation Surgery. Springer; New York: 2015. pp. 351–360. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dezawa A, Kusano S, Miki H. Arthroscopic release of the piriformis muscle under local anesthesia for piriformis syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:554–7. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez-Carro L, Fernandez-Hernando M, Cerezal L. Deep gluteal pain and sciatic nerve entrapment. Presented at the ISHA Annual Scientific Meeting; Rıo de Janeiro Brazil. 9–11 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research: 2016 Update. MLTJ. 2016;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.1.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]