Abstract

Objective

To correlate spinopelvic balance with the development of degenerative spondylolisthesis and disk herniation.

Methods

This was a descriptive retrospective study that evaluated 60 patients in this hospital, 30 patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis at the L4–L5 level and 30 with herniated disk at the L4–L5 level, all of whom underwent Surgical treatment.

Results

Patients with lumbar disk herniation at L4–L5 level had a mean tilt of 8.06, mean slope of 36.93, and mean PI of 45. In patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis at the L4–L5 level, a mean tilt of 22.1, mean slope of 38.3, and mean PI of 61.4 were observed.

Conclusion

This article reinforces the finding that the high mean tilt and PI are related to the onset of degenerative spondylolisthesis, and also concluded that the same angles, when low, increase the risk for disk herniation.

Keywords: Intervertebral disc degeneration, Spine, Spondylolisthesis, Retrospective studies

Resumo

Objetivo

Correlacionar o equilíbrio espinopélvico com o desenvolvimento de espondilolistese degenerativa e hérnia discal.

Métodos

Estudo retrospectivo de caráter descritivo, no qual foram avaliados 60 pacientes, 30 portadores de espondilolistese degenerativa no nível L4-L5 e 30 portadores de hérnia de disco no nível L4-L5, todos submetidos a tratamento cirúrgico.

Resultados

Os pacientes portadores de hérnia de disco lombar no nível L4-L5 apresentaram uma média da inclinação pélvica (TILT) de 8,06, da inclinação sacral (SLOP) de 36,93 e da incidência pélvica (IP) de 45. Nos pacientes portadores espondilolistese degenerativa no nível L4-L5 foi observada uma média da TILT de 22,1, da SLOP de 38,3 e da IP de 61,4.

Conclusão

O presente artigo reforça a descoberta de que as elevadas médias obtidas da TILT e da IP estão relacionadas com o surgimento da espondilolistese degenerativa e ainda conclui que os mesmos ângulos, quando baixos, aumentam o risco para hérnia de disco.

Palavras-chave: Degeneração do disco intervertebral, Coluna vertebral, Espondilolistese, Estudos retrospectivos

Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation is an intervertebral displacement of the nucleus pulposus through the annulus fibrosus; it occurs mainly between the 4th and 5th decade of life, and it is estimated that 2% to 3% of the population may be affected, with a higher prevalence in men.1, 2 In turn, degenerative spondylolisthesis is defined as a slippage of a lumbar vertebra with an intact neural arch, which occurs mostly in adults over 40 years, with a predilection for females.3, 4, 5 Both diseases have a multifactorial etiology that may be associated with smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity, as well as genetic predisposition and anatomical changes.1, 2, 4, 6 Spinopelvic balance has been increasingly studied in degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine as an important factor in the development of these diseases. Spinopelvic balance is the interaction of the spine morphology with the pelvis, and directly impacts the mechanical behavior of the discs, ligaments, and muscle strength. These mechanisms allow the individual to remain upright and move, minimizing energy expenditure.2, 7, 8, 9, 10 Currently, the treatment of these pathologies is conservative; in cases with greater symptom severity and lack of response to conservative treatment, surgical treatment is indicated.2, 11

Although diseases such as lumbar disc herniation and degenerative spondylolisthesis are common in the population, no studies that assessed and compared spinopelvic balance in these patients were retrieved from the literature. Therefore, the authors conducted the present study in order to better understand spinopelvic balance, the relationship of its biomechanics with the development of spondylolisthesis and disc herniation, as well as to be able to make an early identification of patients at risk of developing these diseases. By understanding spinopelvic balance, preventive measures or even better treatment for these diseases can be developed.

Methods

This was a descriptive and retrospective study that evaluated 60 patients, 30 with degenerative spondylolisthesis at L4–L5, and 30 with disc herniation at the L4–L5 level, all of whom underwent surgical treatment. All patients were assessed by lumbopelvic radiography in profile; magnetic resonance imaging was also used for the diagnosis of disc herniation.

Inclusion criteria in group I were patients with lumbar herniation at L4–L5 and refractory to conservative treatment after 20 physiotherapy sessions without instability criteria observed at lumbar radiography. Group II included patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis at the L4–L5 level, classified according to Wiltse, Newman, and Macnab, with failure of conservative treatment with physical therapy and medication for analgesia. Both groups of patients underwent surgical treatment at Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitoria (ES).

Exclusion criteria comprised patients with herniated disc at other levels, those lost to follow-up, or those who did not undergo surgical treatment. In group II, patients with other types of spondylolisthesis, at levels other than L4–L5, or who did not undergo surgical treatment were excluded.

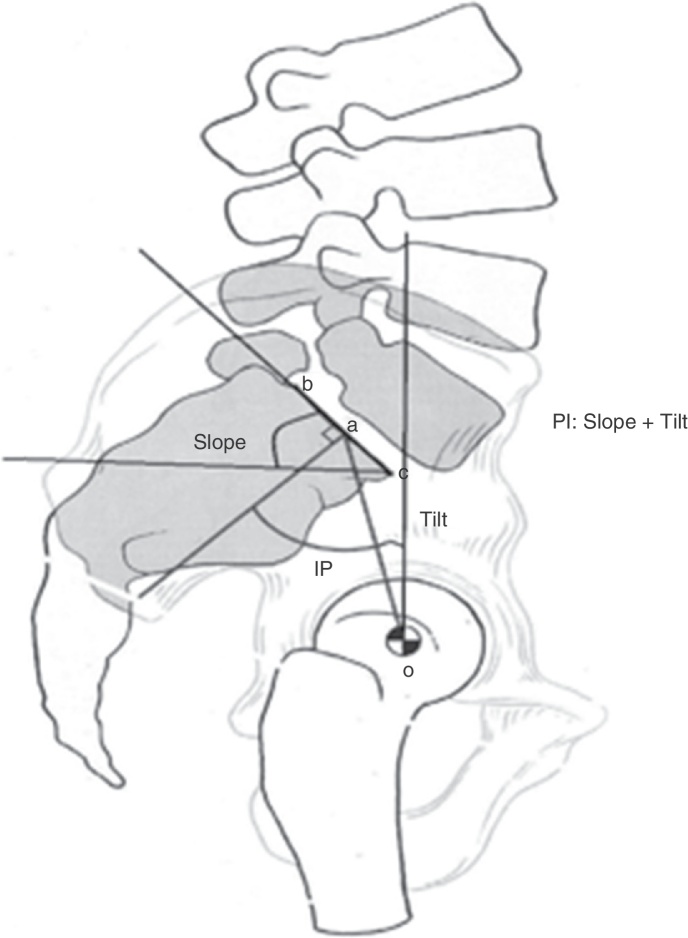

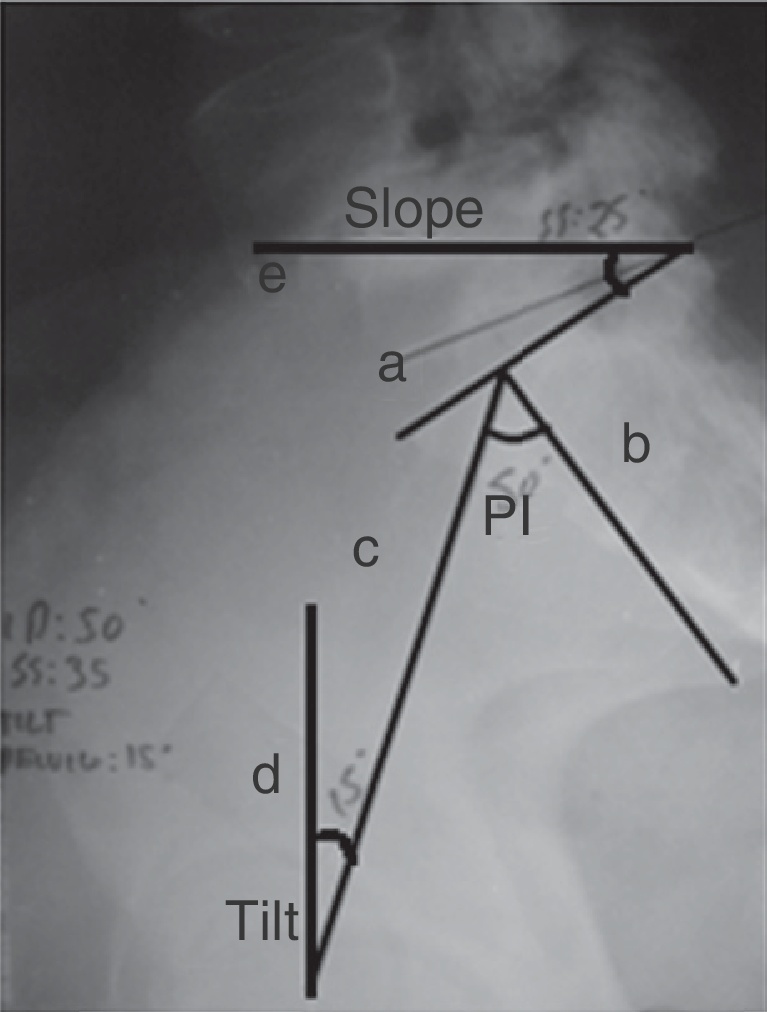

To assess spinopelvic balance, X-ray imaging in orthostatic position (Fig. 1) was used, in which the following could be analyzed: pelvic incidence (PI), through the intersection of the lines that pass through the midpoint of both centers of the femoral heads and the midpoint of the sacral plateau with the line perpendicular to the sacral plateau; sacral slope (SS), assessed through the intersection of lines parallel to the sacral plateau and parallel to the ground; and pelvic tilt (PT), which was assessed by the intersection of the lines that cross the midpoint of both centers of the femoral heads and the midpoint of the sacral plateau with the line perpendicular to the ground.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of PT, SS, and PI. PT, pelvic tilt; SS, sacral slope; PI, pelvic incidence. (a) Sacral plate; (b) line perpendicular to the midpoint of the sacral plate; (c) line between the center of the femoral head and the mean sacral point; (d) reference line of the vertical plane; (e) reference line of the horizontal plane.

Results

The assessment of the parameters involved in spinopelvic balance in patients with lumbar disc herniation at the L4–L5 level indicated a mean PT of 8.06, mean SS of 36.93, and mean PI of 45 (Table 1). In turn, a mean PT of 2.1, mean SS of 38.3, and mean PI of 61.4 was observed in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis at the L4–L5 level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of the means of spinopelvic balance parameters using Student's t-test.

| Disc hernia | Spondylolisthesis | |

|---|---|---|

| Tilt | 8.06 | 22.1 |

| Slope | 36.93 | 38.3 |

| PI | 45.0 | 61.4 |

After statistical analysis, the variables were compared using Student's t-test, which indicated that mean SS results did not differ between groups of herniated disc and spondylolisthesis. This was demonstrated with a p-value above 5% (p = 0.483). In turn, mean PI and PT variables presented statistically significant differences between groups, both with significance levels lower than 5% (p = 0.000 for both).

Discussion

Proper spinopelvic balance allows the individual to remain upright in a stable manner with a minimum of muscular effort; its imbalance causes pain and decreased quality of life.

Spinopelvic balance is determined by the association of pelvic alignment with the lumbar spine. In this geometric construction, the superior angle of the S1 endplate with a horizontal line (sacral slope) is equal to the lower lumbar lordosis angle. Through profile radiograph, the pelvic reference points can be identified, which contribute to determine sagittal balance, including the superior point of the S1 endplate and the center of the femoral head. Through these points, three angles can be determined: PI, PT, and SS. PI is the sum of PT and SS; therefore, PI is strong determinant of the spatial orientation of the pelvis in the standing position, i.e., the higher the PI, the higher is PT, or SS, or both (Fig. 2). It is important to understand that PI is a measure of a static structure, while PT and SS vary according to whether the patient is in the upright or sitting position, as they assess the angle of the sacrum/pelvis in relation to the femoral head.10

Fig. 2.

Slope/tilt/PI.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is defined as the slippage of the lumbar vertebra with an intact neural arch, occurring mainly between L4–L5. With this sliding, the entire trunk moves along with the changed vertebra, resulting in clinical consequences for the patient. The association between excess weight and a relative vertical slope of the S1 endplate increases the chances of an anterior slip at the L4–L5 level. Other factors also predispose mechanically and non-pathogenically to degenerative spondylolisthesis. These include sagittal orientation, osteoarthritis of the joints, paraspinal muscular dystrophy, and loss of ligament strength.4

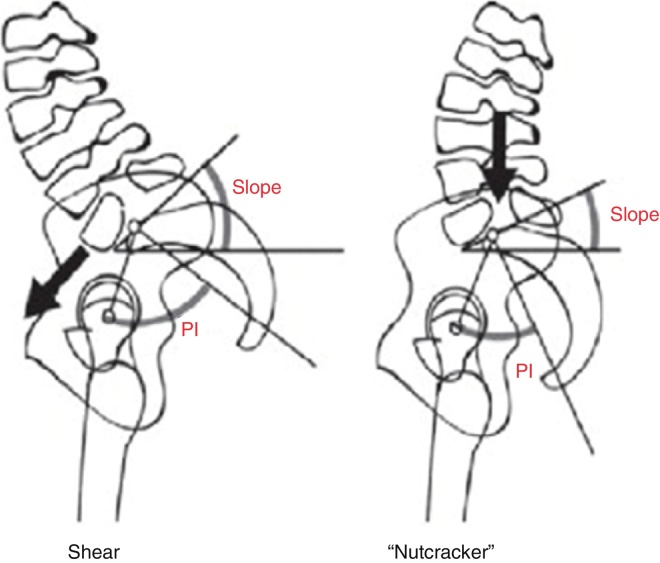

Not all patients with spondylolisthesis have the same PI angle. Spondylolisthesis can be classified as high-grade (group 0, 1, or 2, or slip higher than 50%) and low grade (groups 3 and 4 or slip less than 50%).5, 11 According to Labelle et al.,11 low-grade spondylolisthesis is divided into three groups: type 1 (nutcracker type) with PI < 45°; type 2 with normal PI (between 45° and 60°); and type 3, with PI > 60° (shear type). According to these authors, patients with high PI and high SS have increased shear forces in the lumbosacral junction, which causes greater strain on joints and the shear type. Moreover, patients with low PI and low SS may present an impact on the posterior elements between of L5, L4, and S1 during extension, which causes a nutcracker effect (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Shear and nutcracker types.

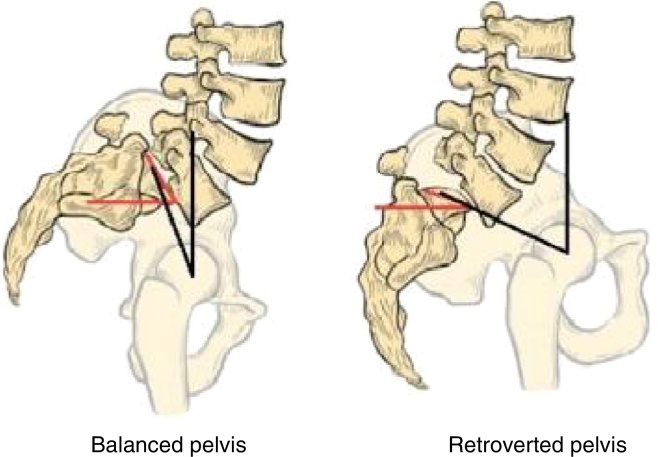

High-grade spondylolisthesis is divided into two groups: balanced and unbalanced pelvic positioning (Fig. 4). The balanced group includes patients who present high slope and low tilt in the orthostatic position. Patients in the unbalanced group present, in the standing position, pelvis in retroversion and a vertical sacrum, which corresponds to low SS and high PT.5, 10 It has been demonstrated that almost all individuals with high vertebral slippage have a mean PI > 60°.5

Fig. 4.

Balanced and retroverted pelvic posture.

Source: Tibet MA. Conceitos atuais sobre o equilíbrio sagital e classificação da espondilólise e espondilolistese. 2014; 49 (1): 3–12.

Forces generated by an increase in lumbar lordosis lead to development and progression of spondylolisthesis. Increased PI is associated with increased lumbar lordosis, which predisposes to mechanical changes of the lumbar and lumbosacral junction and increases the risk of spondylolisthesis.2, 12 According to Roussouly et al.,2 patients with hyperlordosis and hyperkyphosis have high spinopelvic balance. Therefore, they are at greater risk for spondylolisthesis.

A herniated disc is represented clinically by pain known as sciatica, which is triggered by the mechanical compression on the nerve root caused by disc herniation. Conservative treatment with physical therapy and medication for pain control is usually effective. Only a small percentage of these patients require surgery. This is a multifactorial disease; the present article associated spinopelvic imbalance with the emergence of this disease.1, 2

An asymptomatic population with no history of orthopedic disease was assessed in the study by Roussouly et al.,2 in 2005, which showed a mean PI angle of 51.9°. In their study, Schuller et al.4 concluded that higher PI makes the individual more susceptible to developing degenerative spondylolisthesis, and facilitates its progression.

In the present study, patients with spondylolisthesis had a mean PI of 61.4°; those with disc herniation had a mean PI of 45°. This proves that patients with higher PI have increased risk of spondylolisthesis and those with lower PI present a higher risk for disc herniation.

Conclusion

This article reinforced the finding that the high mean values of PI and PT are related to the onset of degenerative spondylolisthesis; the study also concluded that the same angles, when low, increase the risk for disc herniation. It was also possible to conclude that PT and SS are inversely proportional variables. However, both variables are directly proportional to PI; SS is a variable of low significance between the two pathologies. Therefore, only PI and PT contribute to the identification of risk for spondylolisthesis and herniated disc, when they are high or low, respectively.

It can be concluded that spinopelvic imbalance is a risk factor for the emergence of herniated disc and spondylolisthesis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

References

- 1.Vialle L.R., Vialle E.N., Henao J.E.S., Giraldo G. Hérnia discal lombar. Rev Bras Ortop. 2010;45(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roussouly P., Gollogly S., Berthonnaud E., Dimnet J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(3):346–353. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152379.54463.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Love T.W., Fagan A.B., Fraser R.D. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Developmental or acquired? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(4):670–674. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b4.9682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuller S., Charles Y.P., Steib J.P. Sagittal spinopelvic alignment and body mass index in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(5):713–719. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1640-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tebet M.A. Conceitos atuais sobre equilíbrio sagital e classificação da espondilólise e espondilolistese. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsen S., Sonne-Holm S., Rovsing H., Monrad H., Gebuhr P. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: an epidemiological perspective. The Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(1):120–125. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250979.12398.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrey C., Roussouly P., Perrin G., Le Huec J.C. Sagittal balance disorders in severe degenerative spine. Can we identify the compensatory mechanisms? Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl. 5):626–633. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1930-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottfried O.N., Daubs M.D., Patel A.A., Dailey A.T., Brodke D.S. Spinopelvic parameters in postfusion flatback deformity patients. Spine J. 2009;9(8):639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajnics P., Templier A., Skalli W., Lavaste F., Illes T. The importance of spinopelvic parameters in patients with lumbar disc lesions. Int Orthop. 2002;26(2):104–108. doi: 10.1007/s00264-001-0317-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrey C., Jund J., Noseda O., Roussouly P. Sagittal balance of the pelvis–spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases. A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(9):1459–1467. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labelle H., Mac-Thiong J.M., Roussouly P. Spino-pelvic sagittal balance of spondylolisthesis: a review and classification. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl. 5):641–646. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1932-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vialle R., Ilharreborde B., Dauzac C., Guigui P. Intra and inter-observer reliability of determining degree of pelvic incidence in high-grade spondylolisthesis using a computer assisted method. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(10):1449–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]