Abstract

Bilateral stress fracture of femoral neck in healthy young patients is an extremely rare entity, whose diagnostic and treatment represent a major challenge. Patients with history of hip pain, even non-athletes or military recruits, should be analyzed to achieve an early diagnosis and prevent possible complications from the surgical treatment. This report describes a 43-year-old male patient, non-athlete, without previous diseases, who developed bilateral stress fracture of femoral neck without displacement. He had a late diagnosis; bilateral osteosynthesis was made using cannulated screws. Although the diagnosis was delayed in this case, the study highlights the importance of the diagnosis of stress fracture, regardless of the activity level of the patients, for the success of the treatment.

Keywords: Fractures bone, Fractures stress, Femoral neck fractures, Hip pain

Resumo

A fratura de estresse bilateral do colo do fêmur em pacientes adultos sadios é uma entidade extremamente rara, cujo diagnóstico e tratamento representam um grande desafio. Pacientes com história de dor no quadril, mesmo se não forem atletas ou militares, devem ser analisados para se obter um diagnóstico precoce e prevenir possíveis complicações provenientes do tratamento cirúrgico. Este relato descreve um paciente de 43 anos, não atleta, do gênero masculino, sem doenças prévias, que desenvolveu fratura de estresse do colo do fêmur bilateral sem desvio, diagnosticado e tratado tardiamente com osteossíntese bilateral com parafusos canulados. Apesar de o diagnóstico ter sido tardio nesse caso, enfatiza-se a importância de se obter diagnóstico de fratura de estresse, independentemente do nível de atividade dos pacientes, para o sucesso do tratamento.

Palavras-chave: Fraturas ósseas, Fraturas de estresse, Fraturas do colo femoral, Dor no quadril

Introduction

Femoral neck stress fracture is an uncommon injury, and bilateral fractures are even rarer. This location corresponds to 5% of all stress fractures, and are more common among athletes (11%), military personnel, the elderly, and individuals with metabolic disorders, being rarely found in healthy individuals.1, 2

The homeostasis of bone tissue requires continuous synthesis and absorption of bone components. Under normal conditions, there is a balance between osteoblastic reconstruction and osteoclastic resorption.3, 4, 5 Osteoclastic activity reaches a peak at three weeks after the beginning of the repetitive stress on the bone.3, 6, 7 The accumulation of abnormal mechanical load on a given area of the bone may alter the equilibrium in favor of catabolic osteoclast activity and pathologically increase bone resorption, producing microfractures in the bone.4, 8

Etiologically, stress fractures can be divided into two types: (1) fatigue, which is secondary to an abnormal stress applied on a bone with normal structure and elasticity9, 10, 11 (in the femoral neck these fractures are often observed in military personnel and long-distance runners)12, 13; (2) by the impairment of normal muscular force applied to the bone with poor structure and elasticity9, 10, 13 (occurs more frequently in older patients and is often associated with postmenopausal osteoporosis or other types of osteoporosis caused by rheumatoid osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, or use of corticosteroids).9, 10, 14, 15

This report presents a rare case of bilateral stress fracture of the femoral neck in a young, healthy, non-athlete patient.

Case report

Male patient, 43, electrician, non-athlete, smoker, with no history of metabolic disease, diabetes, impaired renal function, or use of corticosteroids. He reported pain in both hips for a year when in professional activity, which reduced at rest. During this period, he was seen in various outpatient clinics and diagnosed with tendinitis or pain due to overload of the hip joint, and was treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Physical examination revealed discrete limping with painful facies, functional impairment, especially in internal rotation. Radiographic examination showed a bilateral coxa vara with cortical interruption and a sclerotic area in both femoral necks (Fig. 1). CT scan confirmed the diagnosis and narrow femoral necks were observed (Fig. 2). As the diagnosis had already been determined by radiography, further examinations, such as magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) or bone scan, were not necessary. The treatment was fixation with two 7-mm cannulated screws, as the femoral neck was too narrow for the placement of three screws or a sliding hip screw (Fig. 3). As fixation was performed in both hips, the patient was oriented to not bear weight for six weeks; thereafter, assisted loading with crutches was authorized.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis disclosing bilateral cortical interruption of the femoral neck.

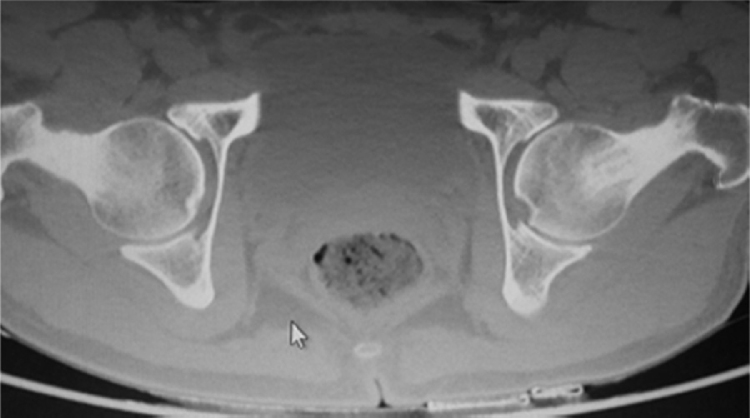

Fig. 2.

CT scan image in axial section of the femoral neck region of both hips, showing a narrow and sclerotic femoral neck.

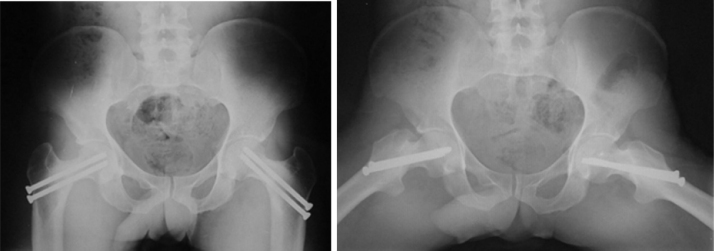

Fig. 3.

Panoramic anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the hips showing the fixation of both femoral necks with two cannulated screws.

Discussion

An epidemiological review revealed numerous risk factors for the development of stress fractures, including female gender, age, low bone density and bone strength, low aerobic conditioning, low level of physical activity in the past, smoking, and excessive running.16 Apulia et al.17 found a correlation between low bone mineral density in the femur and stress fracture in military personnel. These fractures are also found in patients with an abnormal femoral anatomy, renal osteodystrophy, use of corticosteroids, amenorrhea, and osteomalacia.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Most reports of bilateral stress fracture are related to bone insuficiency and are observed in elderly patients. Therefore, the authors believe that the present case is truly rare, as it occurred in a young adult with no evidence of previous illness or metabolic abnormality that could explicate the fracture.

Naik et al.25 have shown that repetitive activity could produce an abnormal stress in both hips. Thus, a bilateral femoral neck stress fracture could occur in non-athlete patients without bone changes. Some authors believe that repetitive load on the hip abductor muscles may lead to muscle fatigue and loss of the shock absorption capacity. Muscle fatigue affects the position of the body's center of mass, and alters the pattern of stress and strain on the femoral neck. Clinical and biomechanical studies have suggested that, due to muscle fatigue, patients develop a compensatory gait that modifies the forces acting on the hip, thus precipitating a femoral neck stress fracture.26, 27

The complaints include groin, thigh, or knee pain reducing at rest which may represent a difficult diagnosis due to the vague presentation of symptoms.2, 28 Thus, these patients are often treated for muscle strain, tendinitis, or early onset hip osteoarthrosis.29 Pihlajamäki et al.30 noted that these complaints should raise a high degree of suspicion for femoral neck stress fracture in healthy, young, male patients who report pain in the groin and/or hip during physical activities. It is also important to note that stress fractures, although symptomatic, are not incapacitating unless they become acutely displaced and/or modify the hip joint.25

Approximately 75% of femoral neck stress fractures may be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed on physical examination.31 When both sides are involved, the percentage of misdiagnoses increases even further, as they are often undisplaced.32 Clinical examination is also non-specific; there may be pain at hip rotation, especially with limitation and pain during internal rotation.

At the onset of symptoms, radiographic examination may be normal. Usually, radiographs demonstrate bone changes two or three weeks after the onset of symptoms; these alterations are diagnosed in less than 10–29% of cases18, 24 During radiographic examination, it is important to keep the lower limb in internal rotation, so that the entire length of the femoral neck is better shown. CT scan may help diagnosing, but MRI and bone scan are considered to be the most suitable exams for early diagnosis. Bone scan with technetium-99m (99mTc) is more sensitive in bone remodeling areas, but it lacks specificity due to similar findings in cases of infection, osteonecrosis, and tumor. MRI is considered to be 100% sensitive, specificand more accurate for early diagnosis and for differentiation with tumor and infection.19, 23, 24, 33 The authors agree with Naik et al.25: when the fractures are evident in the initial radiograph, there is no need for additional tests to confirm the diagnosis. In the present case, CT scan helped not only in diagnosis, but also evidenced a very narrow femoral neck bilaterally, which helped define the surgical technique to be used.

Treatment of femoral neck stress fractures is still a great challenge for surgeons. Upon radiographic examination, two types of fracture can be identified: tension and compression. The most concerning are those caused by tension, as they may displace and, if undiagnosed, cause late osteonecrosis of the femoral head.34 In young and active individuals with bilateral stress fracture of the femoral neck, even in non-displaced fractures, prolonged bed rest is not recommended or reliable. Osteosynthesis and early referral for physical activity are needed. However, complications such as avascular necrosis, re-fracture, varus collapse, and nonunion have been reported after stabilization with multiple screws or sliding hip screw.18 In this case report, the patient was young, active, and the fracture showed no displacement. Two cannulated screws were indicated for fixation of the fracture. This indication was made after surgical planning, through the analysis of the CT, which indicated that the femoral neck was too narrow. Therefore, the possibility of stabilization with a sliding hip screw was discarded, and the authors decided to use three cannulated screws.

The diagnosis of femoral neck stress fracture in young and active patients without evidence of prior metabolic disease is difficult to make. If radiographs are inconclusive, bone scan and MRI (gold standard) are important for the diagnosis. Although in this case the diagnosis was late, the authors emphasize the importance of obtaining the diagnosis of stress fracture for successful treatment, regardless of the patient's level of activity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Service of Orthopedy and Traumatology, Hospital Santa Teresa, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil.

References

- 1.Fullerton L.R., Jr., Snowdy H.A. Femoral neck stress fractures. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):365–377. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lassus J., Tulikoura I., Konttinen Y.T., Salo J., Santavirta S. Bone stress injuries of the lower extremity: a review. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73(3):359–368. doi: 10.1080/000164702320155392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khadabadi N.A., Patil K.S. Simultaneous bilateral femoral neck stress fracture in a young stone mason. Case Rep Orthop. 2015;2015:306246. doi: 10.1155/2015/306246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamay A., Tschantz P. Mechanical influences in bone remodeling. Experimental research on Wolff's law. J Biomech. 1972;5(2):173–180. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(72)90053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterling J.C., Edelstein D.W., Calvo R.D., Webb R., 2nd Stress fractures in the athlete. Diagnosis and management. Sports Med. 1992;14(5):336–346. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones B.H., Harris J.M., Vinh T.N., Rubin C. Exercise-induced stress fractures and stress reactions of bone: epidemiology, etiology, and classification. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1989;17:379–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallis R.E., Jones K. Stress fractures in athletes. How to spot this underdiagnosed injury. Postgrad Med. 1991;89(6):185–188. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11700927. 191–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werntz J.R., Lane J.M. The biology of pathologic fracture repair. In: Lane J.M., Healey J.H., editors. Diagnosis and management of pathologic fractures. Raven; New York: 1993. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daffner R.H., Pavlov H. Stress fractures: current concepts. Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159(2):245–252. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.2.1632335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romani W.A., Gieck J.H., Perrin D.H., Saliba E.N., Kahler D.M. Mechanisms and management of stress fractures in physically active persons. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):306–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson P.J., Lucchesi B.R. Free radicals and myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110(1):13–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pihlajamäki H.K., Ruohola J.P., Weckström M., Kiuru M.J., Visuri T.I. Long-term outcome of undisplaced fatigue fractures of the femoral neck in young male adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(12):1574–1579. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.17996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbot J.C., Cox G., Townend M., Langham M., Parker P.J. Femoral neck stress fractures in military personnel – a case series. J R Army Med Corps. 2008;154(1):47–50. doi: 10.1136/jramc-154-01-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umans H., Pavlov H. Stress fractures of the lower extremities. Semin Roentgenol. 1994;29(2):176–193. doi: 10.1016/s0037-198x(05)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kathol M.H., el-Khoury G.Y., Moore T.E., Marsh J.L. Calcaneal insufficiency avulsion fractures in patients with diabetes mellitus. Radiology. 1991;180(3):725–729. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.3.1871285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones B.H., Thacker S.B., Gilchrist J., Kimsey C.D., Jr., Sosin D.M. Prevention of lower extremity stress fractures in athletes and soldiers: a systematic review. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24(2):228–247. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pouilles J.M., Bernard J., Tremollières F., Louvet J.P., Ribot C. Femoral bone density in young male adults with stress fractures. Bone. 1989;10(2):105–108. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(89)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diwanji S.R., Kong I.K., Cho S.G., Seon J.K., Yoon T.R. Displaced stress fracture of the femoral neck treated by valgus subtrochanteric osteotomy: 2 case studies. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(9):1567–1570. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurdezi S., Trehan R.K., Rickman M. Bilateral undisplaced insufficiency neck of femur fractures associated with short-term steroid use: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:79. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson C., Ekenman I., Törnkvist H., Eriksson E. Stress fractures of the femoral neck in athletes. The consequence of a delay in diagnosis. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(5):524–528. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karapinar H., Ozdemir M., Akyol S., Ulkü O. Spontaneous bilateral femoral neck fractures in a young adult with chronic renal failure. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(1):82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chadha M., Balain B., Maini L., Dhal A. Spontaneous bilateral displaced femoral neck fractures in nutritional osteomalacia – a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(1):94–96. doi: 10.1080/000164701753606770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haddad F.S., Mohanna P.N., Goddard N.J. Bilateral femoral neck stress fractures following steroid treatment. Injury. 1997;28(9–10):671–673. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(97)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa J., Amano R., Haro H., Sato E., Koyama K., Hamada Y. Fatigue fracture of the bilateral femoral neck in the elderly. Orthopedics. 2008;31(11):1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naik M.A., Sujir P., Tripathy S.K., Vijayan S., Hameed S., Rao S.K. Bilateral stress fractures of femoral neck in non-athletes: a report of four cases. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markey K.L. Stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6(2):405–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devas M.B. Stress fractures of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47(4):728–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naranje S., Sezo N., Trikha V., Kancherla R., Rijal L., Jha R. Simultaneous bilateral femoral neck stress fractures in a young military cadet: a rare case report. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2012;22(Suppl. 1):103–106. doi: 10.1007/s00590-011-0864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egol K.A., Koval K.J., Kummer F., Frankel V.H. Stress fractures of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(348):72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pihlajamäki H.K., Ruohola J.P., Kiuru M.J., Visuri T.I. Displaced femoral neck fatigue fractures in military recruits. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(9):1989–1997. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Provencher M.T., Baldwin A.J., Gorman J.D., Gould M.T., Shin A.Y. Atypical tensile-sided femoral neck stress fractures: the value of magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(6):1528–1534. doi: 10.1177/0363546503262195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright R.C., Salzman G.A., Yacoubian S.V., Yacoubian S.V. Bilateral femoral neck stress fractures in a fire academy student. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):767. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100826-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailie D.S., Lamprecht D.E. Bilateral femoral neck stress fractures in an adolescent male runner. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):811–813. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290062301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clough T.M. Femoral neck stress fracture: the importance of clinical suspicion and early review. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(4):308–309. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]