Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the results and benefits obtained from the topical use of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in patients with infected wounds.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of 20 patients (17 males and three females, mean age 42 years) with infected wounds treated using NPWT. The infected wounds were caused by trauma. The treatment system used was VAC.® (Vacuum Assisted Closure, KCI, San Antonio, United States) applied to the wound in continuous mode from 100 to 125 mmHg. The parameters related to the wounds (location, number of VAC changes, the size of the defects in the soft parts, and the evolution of the state of the wound), length of hospital stay, length of intravenous antibiotic therapy, and complications related to the use of this therapy were evaluated.

Results

The mean length of the hospital stay, use of NPWT, and antibacterial therapy were 41 days, 22.5 days, and 20 days respectively. The use of the VAC led to a mean reduction of 29% in the wound area (95.65–68.1 cm2; p < 0.05). Only one patient did not show any improvement in the final appearance of the wound with complete eradication of the infection. No complication directly caused by NPWT was observed.

Conclusion

NPWT stimulates infection-free scar tissue formation in a short time, and is a quick and comfortable alternative to conventional infected wounds treatment methods.

Keywords: Negative-pressure wound therapy, Wound healing, Wounds and injuries, Infection

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar os resultados e benefícios trazidos pela aplicação tópica da terapia por pressão negativa (TPN) em pacientes com feridas infectadas.

Métodos

Estudo retrospectivo de série de casos composta por 20 pacientes (17 homens e três mulheres e média de 42 anos) com feridas infectadas tratadas pela TPN. As feridas infectadas em sua maioria foram de causa traumática. O sistema de pressão a vácuo usado foi o VAC® (Vacuum Assisted Closure, KCI, San Antonio, Estados Unidos), aplicado à ferida em modo contínuo na ordem de 100 a 125 mmHg. Na casuística, os parâmetros relacionados à ferida (localização, quantidade de trocas do VAC, tamanhos dos defeitos de partes moles, evolução do grau da ferida), o tempo de internamento, o tempo de antibioticoterapia venosa e as complicações relacionadas ao uso da terapia foram avaliados.

Resultados

O tempo médio de internamento, uso da terapia a vácuo e antibioticoterapia foi, respectivamente, de 41, 22,5 e 20 dias. O uso do VAC promoveu uma redução média da área das feridas de 29% (95,65 cm2 para 68,1 cm2; p < 0,05). Apenas um paciente não obteve melhoria do aspecto final da ferida, com erradicação completa da infecção. Nenhuma complicação atribuída diretamente ao uso da TPN foi observada.

Conclusão

A terapia por pressão negativa, por facilitar a formação de um tecido de cicatrização ausente de infecção local num curto intervalo de tempo, representa uma opção rápida e confortável aos métodos convencionais no tratamento de feridas infectadas.

Palavras-chave: Tratamento de ferimentos com pressão negativa, Cicatrização, Ferimentos e lesões, Infecção

Introduction

The association of infection with loss of soft tissue, one of the most complex complications of extremities surgery, leads to difficult problems, such as exposure of implant hardware and sensitive structures such as tendons, nerves, and bone.1, 2 Some of the surgical options for this problem described in the literature include rotation flaps, skin grafting, use of colloids, and flap transfers, among others. All these surgical choices are made after debridement of devitalized tissue and copious irrigation of the injured area.3 Treatment is usually long and leads to complications in many cases, the most common being severe pain during dressing changes.4

One therapeutic option, termed negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), also known as vacuum assisted closure (VAC) dressing, provides the following benefits: control of drainage of fluids, reduction of local edema, reduction of bacterial load, and early development of granulation tissue by angiogenic stimulation.5, 6, 7 Initially described by Argenta and Morykwas,8 this therapy has become an important and effective tool for fighting infection in complex wounds, by acting topically with low complication rate, providing greater comfort to the medical team and patient, as well as reducing time of hospitalization, use of antibiotics, and number of dressing changes.8, 9, 10, 11

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results and benefits brought by the topical application of NPWT in patients with infected wounds.

Material and methods

Between January 2012 and December 2013, 27 patients with infected surgical wounds were treated in a high complexity hospital in Salvador (BA) using the vacuum dressing technique (VAC® Vacuum Assisted Closure, KCI, San Antonio, United States). The following inclusion criteria were adopted: presence of positive culture, use of vacuum drainage for over five days, purulent local drainage, and tissue necrosis. For the present study, a sample composed of 20 patients (Table 1) was selected and retrospectively assessed by collection of data records after approval of the hospital's ethics committee.

Table 1.

Clinical series: data regarding 20 patients before and after VAC.

| Patient | Age | Etiology | Site | Degree after | Area before | Area after | Days of VAC use | Additional procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42 | Diabetic foot | Foot | 1 | 5 | 2 | 18 | No |

| 2 | 58 | Diabetic foot | Foot | 1 | 33 | 25 | 22 | No |

| 3 | 76 | Vascular ulcers | Foot | x | 300 | 294 | 5 | Amputation |

| 4 | 63 | Vascular ulcers | Foot | 1 | 28 | 22 | 18 | No |

| 5 | 59 | Diabetic foot | Foot | 1 | 25 | 19 | 13 | No |

| 6 | 61 | Diabetic foot | Foot | 1 | 6 | 4 | 19 | No |

| 7 | 40 | Motorcycle accident | Foot | 1 | 29 | 18 | 13 | No |

| 8 | 52 | Car crash | Forearm | 2 | 261 | 163 | 22 | Skin graft |

| 9 | 43 | Pressure ulcer | Sacrum | 1 | 173 | 121 | 26 | V-y flap |

| 10 | 55 | Vascular ulcers | Ankle | 2 | 68 | 44 | 49 | V-y flap |

| 11 | 35 | Motorcycle accident | Ankle | 3 | 6 | 4 | 11 | Muscle rotation + skin graft |

| 12 | 32 | Motorcycle accident | Leg | 1 | 222 | 153 | 19 | Skin graft |

| 13 | 38 | Motorcycle accident | Foot | 2 | 157 | 109 | 50 | Skin graft |

| 14 | 48 | Osteomyelitis | Ankle | 1 | 32 | 17 | 35 | No |

| 15 | 57 | Vascular ulcers | Ankle | 1 | 112 | 83 | 26 | Skin graft |

| 16 | 28 | Motorcycle accident | Leg | 1 | 332 | 204 | 20 | Skin graft |

| 17 | 49 | Pressure ulcer | Sacrum | 1 | 38 | 25 | 32 | Skin graft |

| 18 | 25 | Motorcycle accident | Ankle | 1 | 29 | 19 | 28 | Skin graft |

| 19 | 37 | Postoperative infection | Ankle | 1 | 15 | 8 | 9 | No |

| 20 | 55 | Fall | Foot | 1 | 42 | 28 | 20 | Skin graft |

All patients had a minimum follow-up of six months (6–26). Mean age was 42 years (16–75); there were 17 men and three women. Trauma (Fig. 1) was the main cause of hospitalization (nine patients), followed by infection in diabetic ulcer (four cases) and varicose ulcers (four cases). In the group of trauma patients, eight had fractures, six in the foot and ankle (four treated with external fixator and two with plate and screws), one in the tibia (treated with external fixation), and one in the distal radius (treated with intraosseous wires).

Fig. 1.

Patient victim of motorcycle accident. (A) Presence of exposed ankle fracture; (B) External fixation of the ankle and presence of local infection; (C) Appearance after 28 days of VAC therapy; and (D) Skin grafting.

All patients were evaluated together by the hospital infection committee. Clinical and laboratory parameters (local culture, white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein) collected weekly, served as the basis of monitoring and guided the use and duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy (discontinued after normality in the aforementioned parameters). In nine patients (45%), the causative agent was found to be Staphylococcus aureus (Table 2). After diagnosis, all patients underwent surgical treatment (debridement and local wound irrigation), followed by local treatment of the injury with NPWT.

Table 2.

Distribution of the bacteria causing the infection.

| Etiological agent | Number of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 9 | 45 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3 | 15 |

| Escherichia coli | 3 | 15 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 | 10 |

| Others | 3 | 15 |

Technique

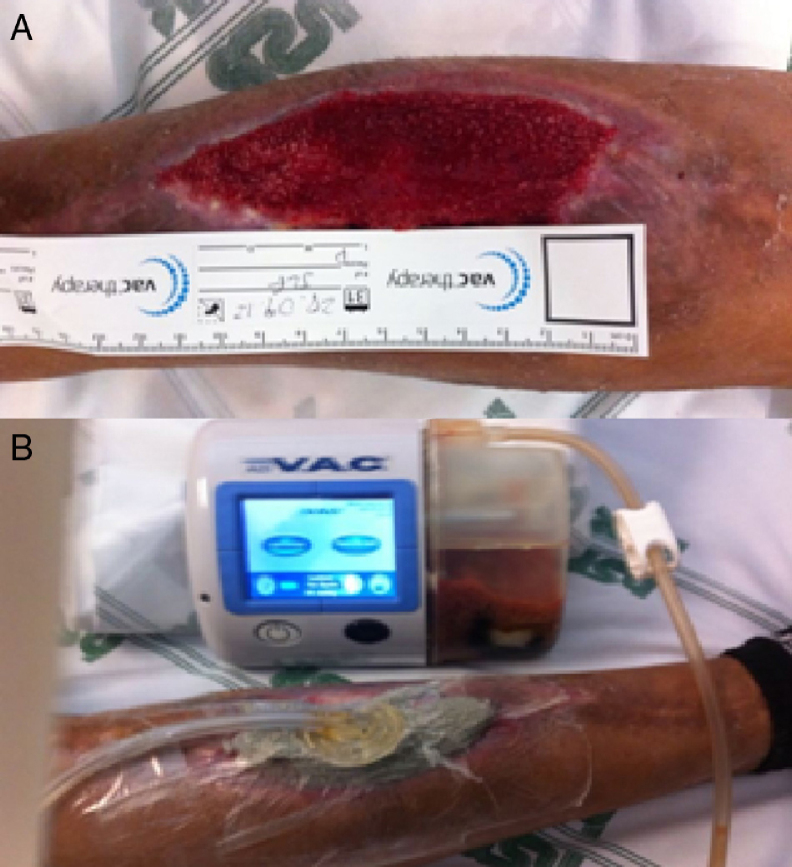

In this series, the VAC® system was used in all patients, consisting of a suction pipe, a reservoir, a vacuum pump, and a multiporous polyurethane sponge. Under sterile conditions, the sponge was cut to precisely cover the extent of the wound, applied directly on it (covering the entire extension), and sealed with a transparent adhesive and vapor-permeable film. This ensemble was connected to the reservoir through a suction tube, allowing for the control of the volume of secretion suctioned and a negative local pressure in continuous mode, on the order of 100–125 mmHg (Fig. 2). The NPWT system was changed every 3–4 days; the first application was in the operating room and the remaining, mostly at bedside. According to patient's clinical development, when necessary, dressing was changed in the operating room after formal debridement. The use of dressing was discontinued after healthy granulation tissue was present. Additional procedures, such as skin grafting and flap rotation, were sometimes required for final coverage.

Fig. 2.

Patient with a picture of infection on the leg. (A) Measurement of the evolution of lesion area during dressing change; and (B) VAC mounting (consisting of foam, transparent film, reservoir, pump, and suction tube).

The following wound-related parameters were analyzed: location, amount of debridement, number of VAC exchanges, and size of soft tissue defect (measured with the aid of a graph paper; Fig. 2) before and after the application of the dressing. The comparative evolution of the wound degree at the beginning and end of therapy was assessed, divided into five groups based on the degree of exposure and the presence of infection, as shown in Table 3.12 The duration of hospital-stay and intravenous antibiotic treatment were also recorded, as well as the complications related to the use of therapy. The collected data were collineated on Excel (Microsoft) and analyzed with the help of Statview® software.

Table 3.

Score used to classify the degree of the wound.

| Score (grade) | Wound status |

|---|---|

| 0 | Closed wound |

| 1 | Skin defect |

| 2 | Bone, implant, or tendon exposure (only one) |

| 3 | Bone, implant, or tendon exposure (two or more) |

| 4 | Presence of local infection |

Results

In the present study, the patients remained in the unit for mean 41 days (17–75), but with mean 20 days of intravenous antibiotic therapy (8–42). The median duration of therapy was 22.5 days (5–50); on average, the dressing was changed every 3.4 days. These patients were taken 82 times to the operating room for wound debridement (mean four times per patient); the total number of dressing changes was 133, 72 of which took place at bedside.

Almost all patients achieved an improvement in the final appearance of the wound site, with infection eradication. One patient, who had an infected varicose ulcer, had an unfavorable evolution, progressing into sepsis; an amputation at the level of the proximal tibia was performed. This patient had undergone only one dressing with the therapy in question.

A 29% mean reduction of wound area was observed, from 95.65 cm2 (5–332) to 68 cm2 after VAC application (2–294; p < 0.05; Table 1). The degree of the injury, initially grade 4 in all cases, reduced to grade 2 in 15 patients (75%). In this group, only seven patients required an additional procedure for wound closure (skin graft). In the entire group, complex procedures (muscle flaps or skin advance graft) were necessary in only three cases.

No complications that could be directly attributed to the use of NPWT, such as deep bleeding or worsening local infection, were observed. Three patients had a mild local itching complaint, which was successfully treated with oral medication, allowing for the maintenance of treatment. A patient who underwent skin grafting on the leg showed scar contracture of the grafted area, which improved after surgical release.

Discussion

The topical use of NPWT has been widely studied in the literature over the past 20 years; the vast majority of clinical trials have shown the effectiveness of this therapy in the treatment of superficial wounds.11, 13, 14 The benefits of such therapy in severe and complicated wounds with extensive loss of soft tissue associated with local infections have been reported in recent years.15, 16 The localized use of NPWT in infected wounds offers advantages such as wound drainage, angiogenesis stimulation, proteinase excretion, and decreased local and systemic bacterial load.6 In the present study, the mean time of VAC® use was 22.5 days and the mean duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy was 20 days, in contrast with data in the literature indicating the use of intravenous antibiotics for six weeks for patients with infected wounds.17, 18 In this treatment period, the VAC was changed every 3.4 days, providing comfort to the patient and the nursing staff, while maintaining a clean dressing without the need for daily changes.

In the present study, healthy infection-free granulation tissue was obtained in 19 patients, as well as a significant decrease in lesion size. These data are similar to those obtained by Gregor et al.,19 who, in a systematic review to assess the effectiveness and safety of VAC compared to conventional therapies for complex wounds, observed a significant reduction of the lesion area for those treated with VAC, without significant adverse effects. In the present study, there were no major complications, such as hemorrhage, which is a well-known complication that may reactivate important initial bleeding. Therefore, the authors recommend treatment discontinuation in the presence of local bleeding, particularly in children.

Damiani et al.,20 in a systematic review, compared VAC and conventional dressings in the treatment of patients with infected wounds after cardiac surgery. In the six studies that evaluated the hospital stay of patients with sternal infection, there was a mean reduction of 7.2 days (95% CI: 3.54–10.82), with no impact, however, in mortality reduction. The main limitation of the present study, apart from the small sample size, was the lack of control group, which did not allow for a direct comparison of patients treated in the same center who underwent conventional method or NPWT.

The authors believe that NPWT may be performed through conventional and low-cost methods (through the vacuum system), as described in the study by Ollat et al.21 Their results are similar to those observed in the present study; nonetheless, those authors reported drawbacks such as the impossibility of an accurate control of the pressure applied to the wound, impossibility of alternating the application of pressure, and the need to change the dressing every 2–3 days to avoid problems such as sponge obstruction by wound secretions.

Conclusion

The present findings add to the growing evidence of the benefits of NPWT as an adjunct therapy in the treatment of infected and complex wounds, especially for facilitating the formation of a local infection-free healing tissue in a short period of time, which reduces the need for complex surgical procedures for the final coverage of important structures. Hence, it is a fast and comfortable alternative to conventional methods in the treatment of infected wounds.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at Hospital São Rafael, Salvador, BA, Brazil.

References

- 1.Bihariesingh V.J., Stolarczyk E.M., Karim R.B., van Kooten E.O. Plastic solutions for orthopaedic problems. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(2):73–76. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0615-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramhøft M., Bødtker S., Carlsen A. Outcome of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9(6):617–621. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clifford R.P. Artmed; Porto Alegre: 2002. Fraturas expostas. Princípios AO do tratamento de fraturas; pp. 617–640. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCallon S.K., Knight C.A., Valiulus J.P., Cunningham M.W., McCulloch J.M., Farinas L.P. Vacuum-assisted closure versus saline-moistened gauze in the healing of postoperative diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2000;46(8):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strecker W., Fleischmann W. Nécroses cutanées traumatiques et non traumatiques. Pansements sous vide. Appareil Locomoteur. 2007:1–5. [Article 15-068-A-10] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mouës C.M., Vos M.C., van den Bemd G.J., Stijnen T., Hovius S.E. Bacterial load in relation to vacuum-assisted closure wound therapy: a prospective randomized trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(1):11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leininger B.E., Rasmussen T.E., Smith D.L., Jenkins D.H., Coppola C. Experience with wound VAC and delayed primary closure of contaminated soft tissue injuries in Iraq. J Trauma. 2006;61(5):1207–1211. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000241150.15342.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morykwas M.J., Argenta L.C., Shelton-Brown E.I., McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(6):553–562. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter J.E., Teot L., Horch R., Banwell P.E. Evidence-based medicine: vacuum-assisted closure in wound care management. Int Wound J. 2007;4(3):256–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vikatmaa P., Juutilainen V., Kuukasjärvi P., Malmivaara A. Negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review of effectiveness and safety. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36(4):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherer S.S., Pietramaggiori G., Mathews J.C., Prsa M.J., Huang S., Orgill D.P. The mechanism of action of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(3):786–797. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818237ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.J., Kim J.W., Oh C.W., Min W.K., Shon O.J., Oh J.K. Negative pressure wound therapy for soft tissue injuries around the foot and ankle. J Orthop Surg Res. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argenta L.C., Morykwas M.J., Marks M.W., DeFranzo A.J., Molnar J.A., David L.R. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl.):127S–142S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222551.10793.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph E., Hamori C.A., Bergman S., Roaf E., Swann N.F., Anastasi G.W. A prospective, randomized trial of vacuum assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic nonhealing wounds. Wounds. 2000;12:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanakaris N.K., Thanasas C., Keramaris N., Kontakis G., Granick M.S., Giannoudis P.V. The efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy in the management of lower extremity trauma: review of clinical evidence. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl. 5):S9–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wongworawat M.D., Schnall S.B., Holtom P.D., Moon C., Schiller F. Negative pressure dressings as an alternative technique for the treatment of infected wounds. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(414):45–48. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000084400.53464.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisno A.L., Stevens D.L. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(4):240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shea K.W. Antimicrobial therapy for diabetic foot infections. A practical approach. Postgrad Med. 1999;106(1):89–94. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.07.602. 85–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregor S., Maegele M., Sauerland S., Krahn J.F., Peinemann F., Lange S. Negative pressure wound therapy: a vacuum of evidence? Arch Surg. 2008;143(2):189–196. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damiani G., Pinnarelli L., Sommella L., Tocco M.P., Marvulli M., Magrini P. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy for patients with infected sternal wounds: a meta-analysis of current evidence. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(9):1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ollat D., Tramond B., Nuzacci F., Barbier O., Marchalan J.P., Versier G. Vacuum-assisted closure: an alternative low cost method without specific components. About 32 cases reports and a review of the literature. e-mémoires de l’Académie Nationale de Chirurgie. 2008;7(4):10–15. [Google Scholar]