Abstract

Objective

To analyze the incidence of ACL and meniscal injuries in a population of recreational and elite athletes from Brazil and the relation of these injuries with their sports activities.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study of 240 patients with ACL and/or meniscal injuries submitted to surgical treatment. Data of patients and sport modality, as well as Tegner score were registered in the first clinical evaluation. The patients were divided into three groups: (1) isolated rupture of the ACL; (2) ACL injury associated with meniscal injury; (3) isolated menisci injury.

Results

The majority of the patients belonged to group 1 (44.58%), followed by group 2 (30.2%) and 3 (25%). Most patients were soccer players. The mean time from sport practice to injury in group 1 was 17.81 years. In group 2, it was 17.3 years, and in group 3, 26.91 years. Soccer athletes presented ACL injury in 0.523/1000 h of practice and meniscal injury in 0.448/1000 h of practice. Before the injury, the mean Tegner score obtained for groups 1, 2, and 3 were 7.18, 7.34, and 6.53, respectively. After knee injury, those values were 3.07, 3.18, and 2.87, respectively.

Conclusion

Soccer was the sport that caused the majority of lesions, regardless the group. Furthermore, patients from groups 1 and 2 had less time of practice prior to the injury (17.81 and 17.3 years) than the patients of group 3 (26.91 years). Women presented a higher risk to develop ACL and meniscal injuries in 1000 h of game/practice. Running, volleyball, and weightlifting are in ascending order of risk for ACL and/or meniscal injury. Regarding the return to sport practice, the efficiency of all athletes was impaired because of the injury.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, Meniscus, Sports medicine, Soccer/injuries

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar a incidência da lesão do LCA e dos meniscos numa população de atletas amadores e profissionais no Brasil e a relação destas lesões com o esporte praticado.

Métodos

Estudo prospectivo observacional de 240 pacientes com lesão meniscoligamentar do joelho desencadeada por diversas atividades esportivas. Dados dos pacientes, do esporte praticado e do questionário de Tegner foram registrados na primeira avaliação clínica. Os pacientes foram divididos em grupos: 1) lesão isolada do LCA; 2) lesão do LCA associada a lesão meniscal; 3) lesão meniscal isolada.

Resultados

A maioria dos pacientes pertencia ao grupo 1 (44,58%), seguido pelos grupos 2 (30,2%) e 3 (25%). O tempo médio de prática esportiva para gerar lesão foi de 17,81 anos no grupo 1, 17,3 no grupo 2 e 26,91 no grupo 3. Atletas de futebol apresentaram lesão de LCA em 0,523/1000 horas de jogo e de lesões meniscais em 0,448/1000 horas de jogo. Antes da lesão, a média de pontos obtidos no questionário de Tegner para os pacientes do grupo 1, 2 e 3 foram de 7,18, 7,34, e 6,53. Após a lesão, este valor caiu para 3,07, 3,18, e 2,87 respectivamente.

Conclusões

A modalidade esportiva mais praticada foi o futebol e causou o maior número de lesões, independente do grupo. Além disso, pacientes do grupo 1 e 2 levaram menos tempo de prática do que os do grupo 3 para sofrerem lesões. As mulheres apresentaram maior risco de lesões de LCA e meniscos por 1000 horas de treino/jogo. Corrida, voleibol e academia estão em ordem crescente de riscos de lesões meniscoligamentares. Quando avaliado o retorno ao esporte, o rendimento de todos os atletas foi prejudicado pela lesão.

Palavras-chave: Ligamento cruzado anterior, Menisco, Medicina esportiva, Futebol/lesão

Introduction

Orthopedic injuries affecting the knee are common and often result in withdrawal of the athlete from training and competitions.1, 2, 3 Injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are common in sports in which the knee performs rotation as in soccer, basketball, and skiing,4 totaling more than 250,000 cases per year.5, 6, 7, 8

In the USA, the most common intra-articular lesion of the knee occurs in the meniscus,9, 10 being the most frequent surgical indication among the orthopedic procedures.9, 11 The menisci play an important role in knee homeostasis, load transmission, shock absorption, lubrication, joint stability and proprioception. Injuries in the menisci can cause pain, disability, as well as accelerate the progression of osteoarthritis of the knee.12

The sport can favor the type of athlete's knee injury. Some sports have a higher prevalence of ACL injuries and others have prevalence of meniscal injuries. Few studies correlate ligament and meniscus injury to the sport practiced.11, 12, 13, 14

The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of ACL and meniscal injury in a population of amateur and professional athletes in Brazil, as well as the relationship of these lesions with the sport practiced and characteristics of the athletes.

Material and methods

This is a prospective observational study, conveyed and duly approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of our institution, which is consistent with the required standards. Patients included in the study signed a free and informed consent.

240 patients with ligament and meniscus injuries in the knee triggered by sporting practices were selected, which were evaluated and followed up individually. Data of the patient and related to sports practice were recorded in the first clinical evaluation. In addition, the Tegner questionnaire was applied to assess the impact of the injury in sporting practices between 2011 and 2014. Patients were divided into Group 1: isolated ACL injury; Group 2: ACL injury associated with meniscal injury; and Group 3: isolated meniscal injuries.

Inclusion criteria were: ACL injury alone or associated with meniscal injury or isolated meniscal injuries; skeletal maturity (>18 years); no signs of osteoarthritis. The criteria for non-inclusion were: presence of other musculoskeletal injuries; option for meniscal suturing; systemic diseases or associated syndromes.

The patients were evaluated and treated as indicated by medical staff: ACL reconstruction using tendons from gracilis and semitendinosus muscles and partial meniscectomy of the medial or lateral meniscus, in accordance with the diagnosis of the injury. Rehabilitation was performed according to protocol established by the medical and physiotherapy staff, with patients returning to sports after six months for ligament injuries and three months for meniscal injuries.

Results

240 patients underwent knee arthroscopy: 107 (44.58%) underwent ACL reconstruction (group 1); 73 (30.2%) underwent ACL reconstruction and partial meniscectomy (group 2); and 60 (25%) underwent isolated partial meniscectomy.

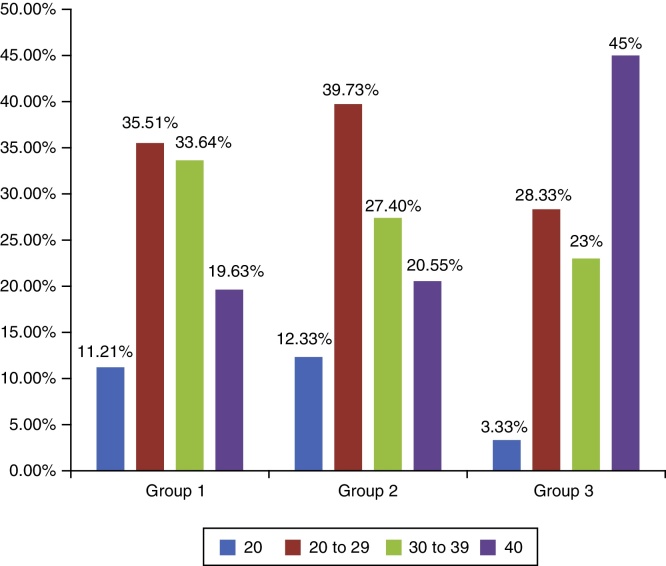

196 patients were male and 44 were female. The average age was 33 years among all patients. Patients of group 1 had an average age of 31 years old, mostly between 20 and 40 years (69.15%). The group 2 patients also had 31 years old on average, and mostly between 20 and 40 years (67.13%). Patients in group 3 had a mean of 39 years old and the majority was over 40 years old (45%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Age distribution among the three evaluated groups. It was observed that patients in group 1 and 2 are younger than those in group 3.

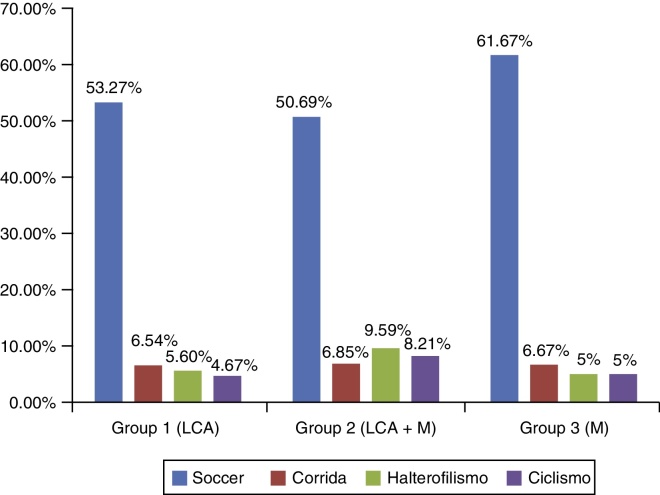

Sports

Group 1 patients had an incidence of injury in the following sports: 53.27% in soccer, 6.54% in racing activities, 5.6% in gym activities, 4.67% in volleyball, cycling and surfing. Other less common sports were jiu-jitsu, capoeira, swimming, hiking, triathlon and dance. 80.37% of isolated ACL injuries in the sport were in men; in soccer, the incidence rises to 87.72%. Females accounted for 100% of the lesions in handball, 57.14% in the race, 40% in volleyball and 16.67% in the gym.

Group 2 patients had incidence of injury in the following sports: 50.69% in soccer, 9.59% in gym activities, 8.21% in cycling, 6.85% in racing and volleyball activities. Other less common forms were handball, triathlon, dance, hiking and jiu-jitsu. 76.71% of the injuries were in males, with incidence in football of 83.79%. Females accounted for 100% of the lesions in handball, 42.86% in gym, 40% in racing, and 20% in volleyball.

The third group of patients had incidence of injury in the following sports: 61.67% in soccer, 6.67% in racing activities, 5% in cycling, gym and jit-jitsu. Other less common sports were: boxing, golf, triathlon, dancing, hiking, capoeira, surfing and tennis. Male patients were affected in 90% of isolated meniscal injuries in sports. In soccer, the incidence was 94.59%. Female patients accounted for 100% of boxing injuries, 50% on golf and jujitsu and 20% in racing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of main sports among athletes treated of ligament and meniscus injuries, noting the dominance of soccer practice in this population.

Practice time

The mean time of sport practice for injury occurrence in group 1 was 17.81 years (22.14 years for running, 18.2 for cycling, 17 for soccer, and 9.87 for gym). In group 2, the mean time was 17.3 years of sport activities (20.8 years for running, 20.11 for soccer, 17 for cycling and 8.14 for gym). In group 3, the mean time was 26.91 years of sports activities (34.67 years for cycling, 33 for racing, 25.59 for soccer and 19.33 for gym).

In soccer, the sport with the highest number of reported cases, the incidence of ACL injury was 0.523/1000 h of playing, with 0.507/1000 h for men and 0.871/1000 h for women. The incidence of meniscal injuries in these athletes was 0.448/1000 h of playing, with 0.435/1000 h for men and 0.596/1000 h for women.

In gym activities, the incidence was 0.69/1000 h of training for ACL injury and 0.55/1000 h for meniscal injury. In volleyball, the incidence was 0.33/1000 h of playing for ACL injury and 0.47/1000 h for meniscal injury. In racing activities, the occurrence was 0.24/1000 h of activity for ACL injury as well as for meniscal injury. In cycling, the occurrence was 0.31/1000 and 0.28/1000 h of activity for ACL and meniscal injury, respectively.

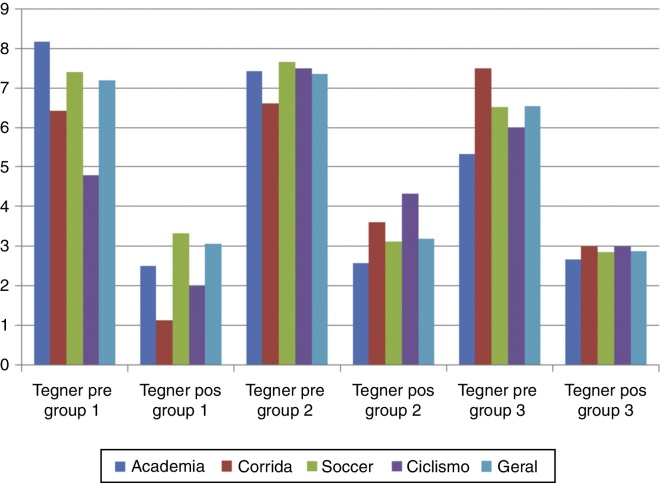

Tegner questionnaire

Before the injury, the average score obtained in Tegner questionnaire for patients in group 1 was 7.18 points. After injury, this value was 3.07 points. The average scores before and after the injury for patients in group 2 were 7.34 and 3.18, respectively. In group 3, the average score was 6.53 before the injury. After the injury, this average decreased to 2.87 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between major sports and Tegner questionnaire pre and post injury. The best results were cycling (Group 1), racing (Group 2) and gym (Group 3). The worst results were gym (Group 1 and 2) and racing.

Discussion

In a first report of athlete population in Brazil, it was observed that the characteristics of knee injuries are different according to age, sport and time of activity. The sport involved at the time of injury reflects the involvement of cultural character in the prevalence of results. We noticed that the average age of patients with meniscal injury is higher than that of patients with ligament injury, once the first injury has a degenerative character and second injury has a traumatic character.

In all groups, the most harmful sport was soccer, followed by racing in the isolated ligament and meniscus injuries group and gym activities in the associated injuries. The performance of all athletes decreased after the injury. In the Tegner scale, groups lost an average of 40–55% of its sport performance. In a ten-year study conducted in Switzerland, Majewski et al. found conflicting results: soccer predominates as the main sport (35%), however skiing on snow comes as a second sport (26%), which is normal since in that country this type of practice is very common.15

Analyzing the results, it is noted that an important risk factor is the period of sport practice. Soccer is, by far, the main cause of injury as it is, invariably, the most popular sport in the studied countries. Sports with impact are great causes of knee injuries and differ according to the country by their own geo-cultural characteristics of the different studied populations. The presence of sports with impact, trauma, and rotational movements of the knee are innate characteristics to meniscus and ligament injuries.16 In groups 1 and 2 the average years of sport practice were similar. Racing was the sport with more practice time to onset of the injury, which was expected since it promotes the emergence of injury with degenerative character. In recent years, amateur racing practice has gradually increased in Brazil and has several cardiovascular benefits for the population. But the practice without guidance of an adequate professional can increase the chances of degenerative knee injuries. These numbers are expected to increase as this sport has become increasingly common in Brazilian cities. In group 3, injuries emerged with more time of sport practice: 26.9 years, with cycling the sport that took more time to cause injury, 34 years on average, showing the degenerative characteristic of meniscal injuries. In all groups, soccer emerged as the sport with less practice time compared to lesions appearance: 17 years for group 1 and 2 and 25 years for group 3. Stewin and Camargo reported an average practice time for professional soccer players of 154 months for men and 113 months for women,17 slightly lower values compared to our control group of ligament injuries. The practice time is a natural predictive for degenerative lesions for obvious reasons, even taking into account the type of exercise practiced and variations of impact and rotary movement. However, the intensity of practice is another factor that must be taken into account for both acute and degenerative injuries. In our study, the incidence of knee injuries per hours of practice is similar to that found in the literature for soccer players, both men and women.8 In runners, both the incidence and the intensity of these lesions were related to the intensity of training, being directly proportional to the level of practice.18 Cycling showed approximately half the risk of injury every 1000 h of training when compared to soccer and gym activities and similar values when compared to runners. This is the first report showing this data.

The variance of the Tegner score was present in all groups, with significant loss of performance of all athletes. The reducing of the sporting performance afterwards the injury had already been described by other authors. Bobbi found a variance of 1.6 on the Tegner score in a mixed group of athletes from various sports.19 Andersson-Molina et al. found a variance of 2 points in the Tegner score in non-athlete patients who have undergone partial and full meniscectomy.20 The return to the same level of practice is diminished for several reasons which may be questionable. First, it is known that, especially in professional athletes, the return to sport is orchestrated as early as possible. Studies indicate that the strength of quadriceps and flexor muscle is reduced even a year after surgery.21 Other factors can contribute to the decrease in sport performance, even in patients showing normal postoperative functions. Many athletes feel that ligament knee injuries are a good reason to stop the competitive level and focus their time on social and family life. Other athletes have a psychological obstacle which limits the function in exchange for protection against a possible reinjury.8

This study has some limitations initially once it is an assessment of athletes from different sports, which often have subgroups with small amounts of subjects. In addition, the follow-up period of these athletes, as well as functional evaluation, could be performed after a longer period.

Conclusion

Soccer was the sport that caused the majority of lesions, regardless the group. Besides that, patients from group 1 and 2 had less time of practice (17.81 and 17.3 years) than the patients of group 3 (26.91 years) until suffer the injuries. Women displayed higher risk to develop ACL and menisci injury by 1000 h of game/practice. Running, volleyball and gym are in ascending order of risk for ACL and/or meniscal injury. When evaluated the return to sport practice, the efficiency of all athletes was impaired because of the injury.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Centro de Traumatologia do Esporte, Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Astur D.C., Aleluia V., Veronese C., Astur N., Oliveira S.G., Arliani G.G. A prospective double blinded randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstrings tendon and spinal anesthesia with or without femoral nerve block. Knee. 2014;21(5):911–915. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papalia R., Torre G., Vasta S., Zampogna B., Pedersen D.R., Denaro V. Bone bruises in anterior cruciate ligament injured knee and long-term outcomes. Are view of the evidence. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:37–48. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S75345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brito J., Soares J., Rebelo A. Prevention of Injuries of the anterior cruciate ligament in soccer players. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2009;15(1):62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astur D.C., Batista R.F., Gustavo A., Cohen M. Trends in treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee in the public and private health care systems of Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J. 2013;131(4):257–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2013.1314498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferretti A., Papandrea P., Conteduca F., Mariani P.P. Knee ligament injuries in volleyball players. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(2):203–207. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arliani G.G., Astur D.C., Moraes E.R., Kaleka C.C., Jalikjian W., Golano P. Three dimensional anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament: a new approach in anatomical orthopedic studies and a literature review. Open Access J Sports Med. 2012;3:183–188. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S37203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arliani G.G., Astur D.C., Kanas M., Kaleka C.C., Cohen M. Anterior cruciate ligament injury: treatment and rehabilitation. Current perspectives and trends. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;48(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjordal J.M., Arnly F., Hannestad B., Strand T. Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):341–345. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akatsu Y., Yamaguchi S., Mukoyama S., Morikawa T., Yamaguchi T., Tsuchiya K. Accuracy of high-resolution ultrasound in the detection of meniscal tears and determination of the visible area of menisci. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2015;97(10):799–806. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordenvall R., Bahmanyar S., Adami J., Mattila V.M., Felländer-Tsai L. Cruciate ligament reconstruction and risk of knee osteoarthritis: the association between cruciate ligament injury and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. A population based nation wide study in Sweden, 1987–2009. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(8):e104681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leal M.F., Astur D.C., Debieux P., Arliani G.G., Silveira Franciozi C.E., Loyola L.C. Identification of suitable reference genes for investigating gene expression in anterior cruciate ligament injury by using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makris E.A., Hadidi P., Athanasiou K.A. The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011;32(30):7411–7431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong-On M., Til-Pérez L., Balius R. Evaluation of MRI-US fusion technology in sports- related musculoskeletal injuries. Adv Ther. 2015;32(6):580–594. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branch E.A., Milchteim C., Aspey B.S., Liu W., Saliman J.D., Anz A.W. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopic repair constructs for radial tears of the meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2270–2276. doi: 10.1177/0363546515591994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majewski M., Susanne H., Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: a 10-year study. Knee. 2006;13(3):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordenvall R., Bahmanyar S., Adami J., Stenros C., Wredmark T., Felländer-Tsai L. A population based nationwide study of cruciate ligament injury in Sweden, 2001–2009: incidence, treatment, and sex differences. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1808–1813. doi: 10.1177/0363546512449306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewien E., Camargo O. Ocorrência de entorse e lesões do joelho em jogadores de futebol da cidade de Manaus, Amazonas. Acta Orto Bras. 2005;13(3):141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schueller-Weidekamm C., Schueller G., Uffmann M., Bader T. Incidence of chronicknee lesions in long-distance runners based on training level: findings at MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2006;58(2):286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobbi A., Francisco R. Factors affecting return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon and hamstring graft: aprospective clinical investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(10):1021–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersson-Molina H., Karlsson H., Rockborn P. Arthroscopic partial and total meniscectomy: a long-term follow-up study with matched controls. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(2):183–189. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.30435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvist J. Rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament injury: current recommendations for sports participation. Sports Med. 2004;34(4):269–280. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]