Abstract

Background

A living donor (LD) for liver transplantation (LT) is the best target for minimally invasive surgery. Laparoscope-assisted surgery (LAS) for LDs has gradually evolved. A donor safety rate of 100% should be guaranteed.

Methods

We began performing LAS for LDs in June 2012. The aim of this report is to describe the surgical procedures of LAS in detail, discuss various tips and pitfalls, and address the potential for a smooth transition to more advanced LAS.

Results

Preoperative planning based on three-dimensional image analysis is a powerful tool for successful surgery. The combination of liver retraction/countertraction and the pressure produced by pneumoperitoneum widens the dissectible/cuttable layer, increasing the safety of LAS. A flexible laparoscope provides excellent magnified vision in both the horizontal view along the inferior vena cava, under adequate liver retraction, and in the lateral view, to harvest left-sided grafts in critical procedures. Intentional omission of painful incisions is beneficial for LDs. Hepatectomy using a smaller midline incision is safe if a hanging maneuver is used. Safe transition from LAS to a hybrid technique involving a combination of pure laparoscopic surgery and subsequent open surgery seems possible.

Conclusion

LDLT surgeons have a very broad intellectual and technical frontier.

Keywords: Laparoscopic hepatectomy, donor surgery, donor, laparoscopic surgery, laparoscopy

Introduction

Pure laparoscopic surgery (PLS) has been adopted in various fields. PLS is advantageous in that it entails less blood loss, less pain, a lower morbidity rate, earlier postoperative meal ingestion, and a shorter hospital stay compared with conventional open surgery (OS) [1-4]. The benefits to patients are well validated [1-9]. However, in the field of hepatobiliary pancreatic (HBP) surgery in particular, PLS has developed relatively slowly because of technical difficulties, a protracted learning curve, and massive bleeding [1-3,9,10].

Living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) requires a healthy individual as a living donor (LD). Perioperative damage should be minimized as much as possible, and an LD for LDLT is the best target for minimally invasive surgery [1,5,7,9,11-14] because he or she inherently requires no invasive surgical procedures. Additionally, a donor safety rate of 100% should be guaranteed [6,7,15,16].

Each country has its own health insurance system. The Japanese government employs a universal health insurance system. Therefore, novel surgical procedures in Japan are not authorized until they are included in the health insurance system’s listing by the governmental council. Unfortunately, a few HBP surgeons violated the medical ethics code by ignoring the health insurance system in Japan, and their laparoscopic surgery techniques emerged as a social issue in 2014. However, laparoscopic HBP surgeries potentially have substantial benefits [1-9]. The performance of advanced HBP surgeries should not be compromised by a small number of thoughtless surgeons. Specific regulations and ethical policies for advanced surgeries in LDs should be established for LDLT [15,16], and technological developments should be disseminated worldwide [5,7].

We employ a laparoscope for graft harvesting in LDs and we utilize the concept of laparoscope-assisted surgery (LAS). LAS is not considered a type of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS), but an extension of OS [9,10,12,13,17,18]. Both preoperative imaging techniques and surgical devices are currently well developed [19,20], and hepatectomy procedures via direct vision from a small midline incision are therefore safe [21,22] if a hanging maneuver is used [18,23]. Hence, we herein focus on surgical procedures performed in preparation for a hanging maneuver. We describe our procedures in detail and discuss both tips and pitfalls. In addition, we discuss the potential for smooth transition from LAS to PLS or a hybrid technique (HT).

Patients and methods

Ethical approval

Skilled surgeons of Nagasaki University, Japan previously provided us with instructions regarding their LAS procedures [21,22,24], allowing us to develop our own LAS technique. The LAS protocol used in our LDLT program has been approved by our institutional review board (Approved No. 991; Ethics Review Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan). LAS for LDs was thus introduced to LDLT procedures in June 2012.

Results

Preoperative imaging studies

Volumetric assessment of the hepatic remnant should be performed first to ensure safety for the LD. We use imaging software (HepaVision, MeVis software; MeVisLab, Bremen, Germany) for volumetric analyses of both the hepatic remnant and the graft volume. Precise recognition of the portal vein (PV) and hepatic vein (HV) territories is also important. The predicted territories of portal ischemia due to PV obstruction and venous congestion due to HV sacrifice should be accurately evaluated in both the hepatic remnant and the liver allograft [25].

Anatomical analysis should be performed precisely, especially for LAS. In our institution, detailed analysis is performed by a high-speed three-dimensional (3D) image-analyzing system (Synapse Vincent; Fujifilm Medical, Tokyo, Japan) [19]. Dynamic computed tomography detects the hepatic artery, PV, and HV. Drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography is performed for analysis of the biliary duct, if needed. Drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography is more suitable than magnetic resonance cholangiography for creating such 3D images, although it is associated with a higher rate of allergic response to infused agents [26]. Hence, 3D imaging that articulates the vessels and biliary duct in an all-in-one package can be performed if required because drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography is only performed in selected cases (Fig. 1A).

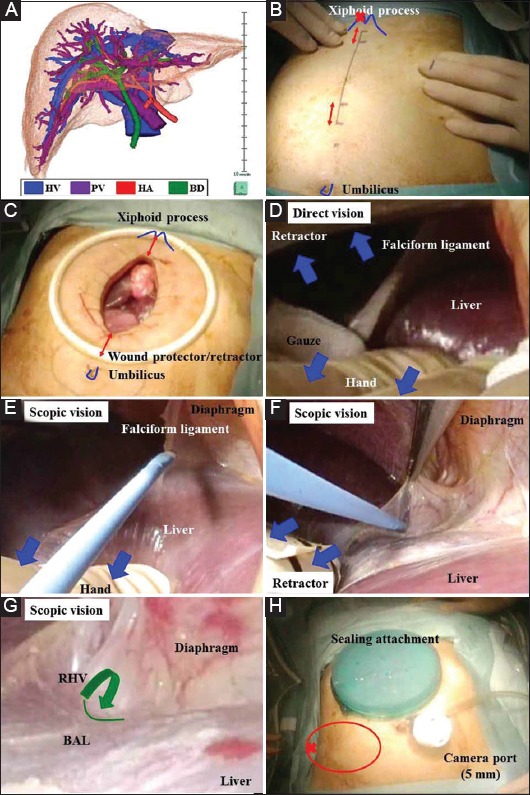

Figure 1.

(A) A three-dimensional image that articulates the vessels (i.e., hepatic vein, portal vein, and hepatic artery) and biliary duct in an all-in-one package should be made preoperatively. (B) An 8-cm mark is made along the midline from a point 2 cm below the xiphoid process. Several 2-cm incisions from the upper and lower sides of the midline incision are added if needed (red arrows). To expose the bare area of the liver in the right subphrenic area in pure laparoscopic surgery or a hybrid technique, a working port should be placed as far toward the head side as possible (red cross). (C) The midline incision is protected and retracted by a wound attachment. (D) Direct vision alone may provide an inadequate surgical field. Adequate retraction of the liver is performed (blue arrows). (E) Scopic vision provides an excellent surgical field for cutting of the falciform ligament and (F) dissection around the right hepatic vein. (G) Scopic vision provides a magnified view. The division between the right and middle hepatic veins is detected (green line) and dissected through the anterior wall of the inferior vena cava (green arrow). (H) The wound is sealed with a gel-type attachment. The camera port is placed at the umbilicus, and a working port is placed at the right lateral wall (red circle). To expose the bare area of the liver at the right subphrenic area in either pure laparoscopic surgery or a hybrid technique, a working port should be placed as far toward the lateral-dorsal side as possible (red cross) BAL, bare area of the liver; BD, biliary duct; HA, hepatic artery; HV, hepatic vein; PV, portal vein; RHV, right hepatic vein

Harvest procedure of right-lobe graft (RLG)

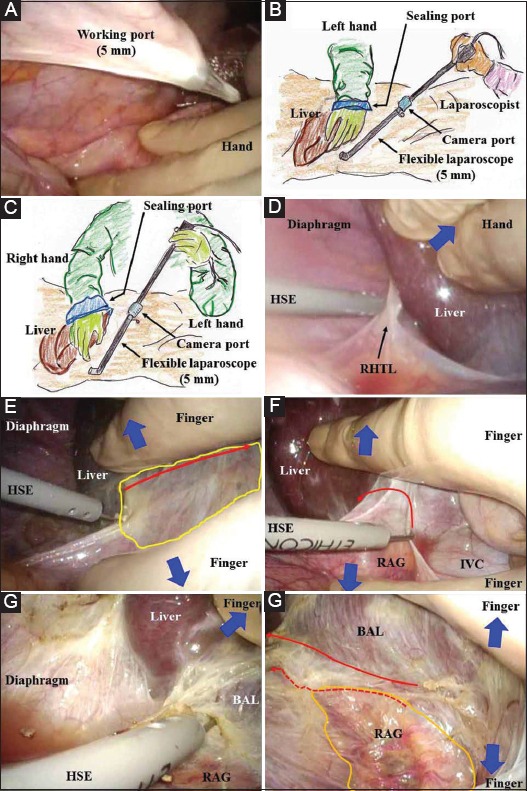

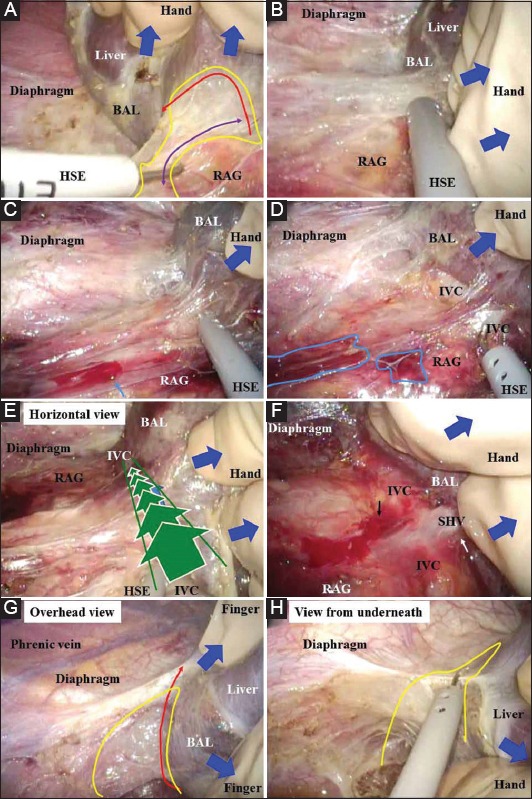

RLG harvesting is performed as follows. The xiphoid process is confirmed. An 8-cm mark is made along the midline starting from a point 2 cm below the xiphoid process (Fig. 1B). Additional 2-cm marks starting from the upper and lower sides of the midline incision are then made to ensure adequate visualization of the HV and hepatic hilum (Fig. 1B, C). A GelPort Laparoscopic System containing a GelSeal cap, Alexis wound protector/retractor, and sterile lubricant is used (Applied Medical Resources Co., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA). The midline incision is protected and retracted by a wound attachment (Fig. 1C). Direct vision alone may provide an inadequate surgical field for further procedures (Fig. 1D). However, the combined use of a laparoscope through the midline incision is an effective solution. Laparoscopic vision provides an excellent magnified field for cutting of the falciform ligament (Fig. 1E), dissection around the right HV (RHV) (Fig. 1F), and detection of the division between the RHV and middle HV (MHV) (Fig. 1G). The 8-cm midline incision is then sealed by a gel-type attachment (Fig. 1H). A 5-mm camera port is placed at the umbilicus and a 5-mm working port in the right lateral wall (Fig. 1H). The intra-abdominal organs are guarded by hand during port placement (Fig. 2A). The surgeon’s left hand, which mainly retracts the liver, is inserted into the abdomen via a sealing port in situations where two assistants (a laparoscopist assistant and a surgical assistant) are present (Fig. 2B). If the assistant surgeon is skillful, his or her right hand is inserted via a sealing port to retract the liver, and a flexible laparoscope is manipulated only by the left hand. If only one assistant is present, he or she assists with surgery and laparoscopy. The right hand of the surgeon maintains close contact with the laparoscope, although the performance of advanced techniques by the assistant is required (Fig. 2C). The right hepatic triangular ligament is cut by a hook-shaped electrode (HSE) under liver retraction (Fig. 2D). The HSE has the advantage of simultaneously cutting and pulling the tissue, creating a safety area in front of the cut tissue. Hence, one working port is usually enough (Fig. 1H). Delicate and detail-oriented retraction/countertraction is performed with the finger, and general and rough retraction/countertraction is performed with the hand (Fig. 2E). The retroperitoneum around the right hepatic triangular ligament, right adrenal gland (RAG), and inferior vena cava (IVC) is cut under countertraction by the fingers and HSE (Fig. 2F, G). The pressure produced by pneumoperitoneum also creates a dissectible and cuttable layer by marked infiltration of carbon dioxide gas. The bare area of the liver is exposed, and the RAG appears as a capsule with its own thin surface membrane (Fig. 2H, 3A). A dissectible/cuttable layer is created by adequate retraction/countertraction with hand or finger assistance and under the pressure of pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 3A). This wide layer is cut as close to the liver side as possible (Fig. 3A, B). Even slightly careless retraction/countertraction may easily result in hemorrhage and/or oozing around the RAG (Fig. 3C, D). Under liver retraction, a horizontal laparoscopic view from the para-IVC (not from Morrison’s pouch) provides an excellent view along the IVC (Fig. 3E). The lateral wall of the IVC is exposed, and the short HVs and hepatocaval ligament are then skeletonized (Fig. 3F). As above, even slightly careless retraction/countertraction easily results in hemorrhage and/or oozing around the IVC (Fig. 3F). Employing the many-angled views of the flexible laparoscope, the liver is removed from the diaphragm without injury (Fig. 3G, H). Simultaneous retraction/countertraction of the liver and pressure induced by pneumoperitoneum helps to create a dissectible/cuttable layer wide enough for dissection; therefore, this layer should be intentionally traced as close to the liver as possible (Fig. 4A, B). Even blunt dissection by a finger works well (Fig. 4A, B). The walls of the RHV and IVC are carefully detected close to the RHV root (Fig. 4C). The wound-sealing attachment is then removed. Direct vision with focal lighting also provides a preferable surgical field for RHV skeletonization (Fig. 4D-F) if a 2-cm upper extensional incision is made (Fig. 1B, C). The cut ends around the RHV from the right and central sides are connected via laparoscopic vision (direct vision provides only a limited view under the right subphrenic space) (Fig. 4G) [18]. The RHV is skeletonized (Fig. 4H) and then hanged with a Penrose drain (Fig. 5A). An extensional incision is added at the lower side if it appears that subsequent procedures at the hepatic hilum are likely to be difficult (Fig. 1B, C).

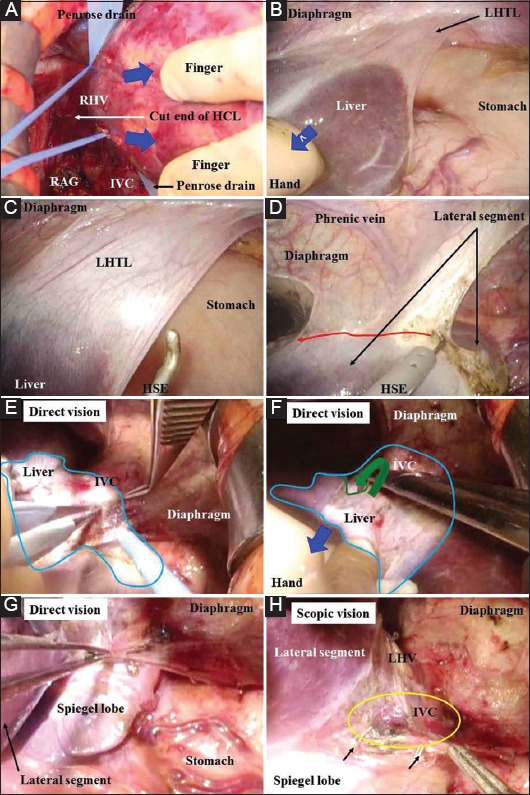

Figure 2.

(A) The intra-abdominal organs should be guarded by the surgeon’s hand during port placement. (B) The left hand is inserted into the abdomen via a sealing port in situations where both a surgical and laparoscopic assistant are present. (C) If the assistant surgeon is well educated and greatly experienced, his or her right hand is inserted via a sealing port to retract the liver, and a flexible laparoscope is then manipulated only by the left hand. A more coordinated surgical field with a magnified view will thus be obtained. (D) The right hepatic triangular ligament is cut by a hook-shaped electrode under liver retraction (blue arrow). To expose the bare area of the liver in the right subphrenic area, a working port is placed as far toward the lateral-dorsal side as possible. (E) Delicate and detail-oriented retraction/countertraction is performed with the finger, and general and rough retraction/countertraction is performed with the hand (blue arrows). The pressure of pneumoperitoneum helps to create a dissectible/cuttable layer by marked infiltration of carbon dioxide gas (yellow area). The retroperitoneum is intentionally cut near the liver (red arrow). (F) The retroperitoneum around the right adrenal gland and inferior vena cava is cut near the liver (red arrow) under the countertraction (blue arrows) and tension created by a hook-shaped electrode. (G) The bare area of the liver is exposed. (H) The retroperitoneum is cut near the liver (solid arrow), not near the right adrenal gland (dotted arrow). The right adrenal gland should be carefully saved with a membrane capsule (orange area) BAL, bare area of the liver; HSE, hook-shaped electrode; IVC, inferior vena cava; RAG, right adrenal gland; RHTL, right hepatic triangular ligament

Figure 3.

(A,B) A dissectible/cuttable layer should be created (yellow area). An adequately wide layer is confirmed with a reciprocating hook (purple arrow) and is cut near the liver (red arrow). (C,D) Even slightly careless retraction/countertraction of the liver may easily result in hemorrhage and/or oozing around the right adrenal gland (aqua arrow and areas). (E) Delicate and detail-oriented retraction/countertraction is performed with the finger, and general and rough retraction/countertraction is performed with the hand (blue arrows). The horizontal view via the laparoscope provides an excellent view along the inferior vena cava (green arrows). The surgical field essentially spreads to the foreground via the laparoscope (green lines). (F) The lateral wall of the inferior vena cava is bared, and then short hepatic veins and the hepatocaval ligament can be skeletonized. Even slightly careless retraction/countertraction will easily result in hemorrhage and/or oozing around the inferior vena cava (black arrow). (G) From an overview provided by laparoscopic vision, the liver is removed from the diaphragm without any injury to the liver or phrenic veins (blue arrows). The bare area of the liver is adequately exposed. The dissectible/cuttable layer is very wide (yellow area) and is intentionally cut as close to the liver as possible (red arrow). (H) The view from underneath also provides an excellent field for cutting a dissectible/cuttable layer (yellow area) BAL, bare area of the liver; HSE, hook-shaped electrode; IVC, inferior vena cava; RAG, right adrenal gland; SHV, short hepatic vein

Figure 4.

(A,B) Simultaneous retraction/countertraction with a hand or finger (blue arrows) and marked infiltration of carbon dioxide gas that created pneumoperitoneal pressure worked well to create a dissectible/cuttable layer (yellow areas). Because this layer was so wide, it was intentionally traced as close to the liver as possible during dissection (red arrows). (C) According to the process of exposure of the bare area of the liver, the walls of the inferior vena cava and right hepatic vein are carefully detected. (D) Direct vision also provides a good surgical field for right hepatic vein detection if a 2-cm extensional incision is made below the xiphoid process. (E) Direct vision requires focal lighting (aqua area). (F) The division between the right hepatic vein and middle hepatic vein is detected (green line) and dissected (green arrow). (G) The cut ends around the right hepatic vein from the central and right sides are connected via scopic vision because direct vision provides only a limited view under the right subphrenic space. (H) The hepatocaval ligament is cut, and the inferior vena cava wall and extrahepatic margin of the right hepatic vein are bared. The right hepatic vein is then skeletonized BAL, bare area of the liver; HSE, hook-shaped electrode; IVC, inferior vena cava; RHV, right hepatic vein

Figure 5.

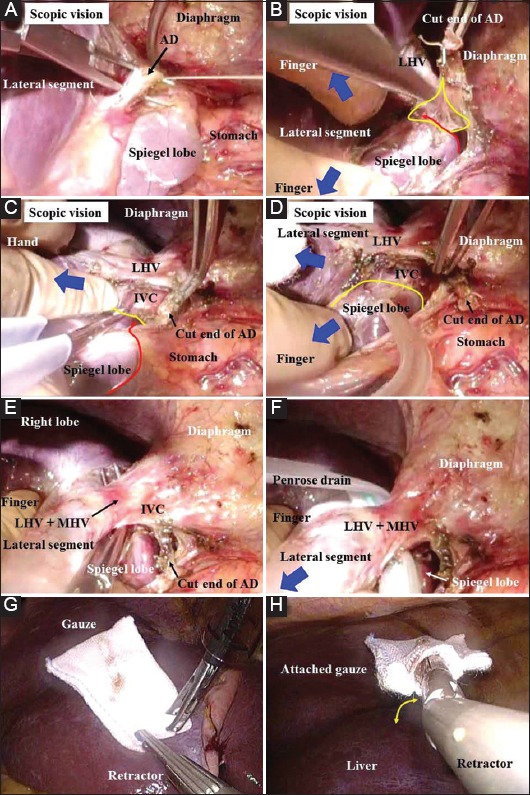

(A) The right hepatic vein is adequately skeletonized and then hanged with a Penrose drain. (B) Delicate and detail-oriented retraction/countertraction is performed with the finger, and general and rough retraction/countertraction is performed with the hand (blue arrows). Use of a laparoscope with pneumoperitoneum provides an excellent surgical field under the left phrenic space. (C) The left hepatic triangular ligament is cut. (D) The cut ends of the membranes from the central and left sides are connected. Injury to the phrenic veins should be avoided. The dissectible/cuttable layer is very wide, as is the right side, and should be intentionally traced as close to the liver as possible (red arrow). (E) Direct vision with an extensional incision provides a preferable surgical field for procedures involving hanging of the left hepatic vein and middle hepatic vein. Direct vision requires focal lighting (aqua area). The pinch-burn-cut technique is useful for dissections around the inferior vena cava. (F) The division between the middle and right hepatic veins is detected (green line) and dissected through the anterior wall of the inferior vena cava (green arrow). Adequate retraction of the liver is performed (blue arrow). (G) The inferior vena cava wall should be completely bared at the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe. The pinch-burn-cut technique works well for this purpose. (H) The phrenic vein is ligated (black arrows) if needed. A perfect dissection of the connective tissues should be completed, especially on the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe (yellow area) HCL, hepatocaval ligament; HSE, hook-shaped electrode; IVC, inferior vena cava; LHTL, left hepatic triangular ligament; RAG, right adrenal gland; RHV, right hepatic vein

Harvest procedure of left-sided graft (LSG)

Laparoscope-assisted removal of the right lobe is performed in the same manner as the procedure described above. The left hepatic triangular ligament is cut (Fig. 5B, C). The cut ends of the membranes from the central and left hepatic triangular ligament sides are connected (Fig. 5D). Simultaneous retraction/countertraction of the liver and pressure induced by pneumoperitoneum widens the dissectible/cuttable layer, and this layer should be intentionally traced as close to the liver as possible (Fig. 5D). The wound-sealing attachment is then removed. Direct vision with an upper extensional incision and focal lighting provides a surgical field for preparation of a hanging maneuver of the left HV (LHV) and MHV (Fig. 5E-G), including dissection around the LHV, MHV, or their common channel (Fig. 5E); detection of the division between the MHV and RHV (Fig. 5F); and skeletonization and subsequent ligation of Arantius’ duct with adequate bareness of the IVC wall on the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe. The pinch-burn-cut technique works well [27] (Fig. 5G). Lateral scopic vision provides an excellent magnified field for ligation of the phrenic vein (Fig. 5H), skeletonization and subsequent ligation of Arantius’ duct (Fig. 6A), complete dissection of the connective tissue on the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe (Fig. 5H, 6B), and adequate bareness of the IVC wall on the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe (Fig. 6C, D).

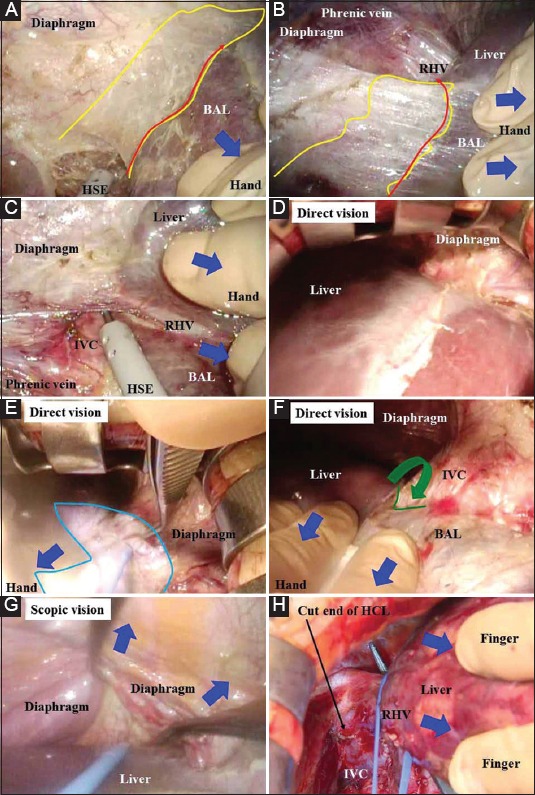

Figure 6.

(A) Arantius’ duct is ligated and then cut. (B-D) Delicate and detail-oriented retraction/countertraction is performed with the finger, and general and rough retraction/countertraction is performed with the hand (blue arrows). The connective tissues should be completely dissected (yellow area). The membrane around Spiegel’s lobe is cut (red line), and the upper side of this lobe is completely bared (yellow line). The pinch-burn-cut technique works well. (E) The inferior vena cava wall is bared sufficiently at the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe. The extrahepatic margin of the common channel of the left and middle hepatic veins is also skeletonized. (F) This common channel is hanged with a Penrose drain. (G) For a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, specialized gauze is prepared for retraction/countertraction of the liver. (H) An articulated fan-shaped retractor attached to specialized gauze is employed for a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery. This device is bendable (yellow arrow) AD, Arantius’ duct; IVC, inferior vena cava; LHV, left hepatic vein; MHV, middle hepatic vein

These procedures, which ensure adequate exposure of the IVC wall, are important for LSG (Fig. 5G, H; 6B-D). The common channel of the LHV and MHV, or LHV, is adequately skeletonized (Fig. 6E). The common channel of the LHV is then hanged with a Penrose drain (Fig. 6F). The lateral laparoscopic view through the midline incision provides excellent magnified vision and works well for harvesting during LSG. An extensional incision at the lower side is added if further procedures at the hepatic hilum are difficult (Fig. 1B, C).

Our procedures for other types of allografts

Our LAS can be applied to other graft types, such as mono-segmental grafts [28], RLG with the MHV [29], or right posterior grafts [26]. Although this may be technically difficult and high-risk in that the cutting surface is set to an 8-cm midline incision, a hanging maneuver of the HV enables a safe hepatectomy even via a smaller midline incision [18,23].

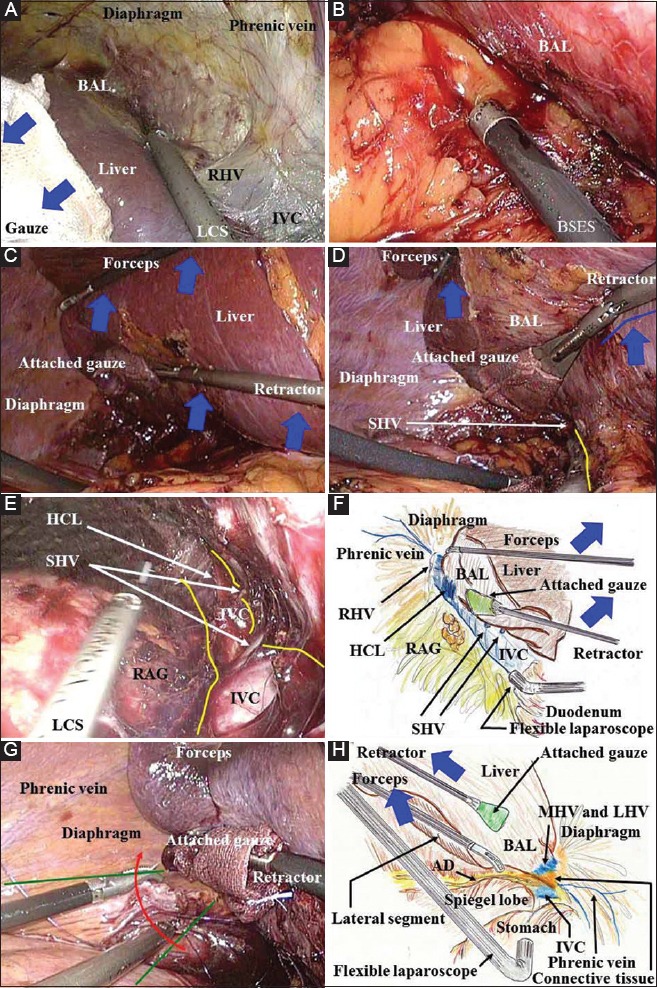

Potentiality of smooth transition to PLS or HT

Currently, in our institution, the rough removal of the liver is achieved by pneumoperitoneum rather than the open method. Here, based on our surgical procedures of PLS for hepatectomy in patients undergoing HBP surgery, we verified and validated the potential for a smooth transition from LAS to an HT or PLS in LDs [9,18,30,31]. Specialized gauze (Deltagauze; Osaki Medical Co., Nagoya, Japan) (Fig. 6G) and an articulated fan-shaped retractor (Fig. 6H) allow for adequate retraction/countertraction without any slippage (Fig. 7A). Additionally, advanced devices for PLS are available (Fig. 7A, B). Laparosonic coagulating shears (Harmonic Ace, Ethicon; Johnson & Johnson, Tokyo, Japan) serve as a useful scalpel that provides reliable hemostasis (Fig. 7A). A button-shaped electrode with suction used in conjunction with a soft-coagulation system (VIO; Erbe, Tübingen, Germany) is an effective tool for secure hemostasis (Fig. 7B). A self-irrigating monopolar electrode (IO advanced, Erbe) is also useful for hemostasis. The assistant surgeon removes the liver using two forceps/retractors (Fig. 7C). Under liver retraction, the lateral wall of the IVC is bared by laparosonic coagulating shears (Fig. 7D), and short HVs (SHVs) and the hepatocaval ligament are then skeletonized (Fig. 7E), as the horizontal view from the para-IVC provides an excellent magnified view along the IVC via the flexible laparoscope (Fig. 7F). This view represents one of the advantages of using a laparoscope (Fig. 3E, 7E, F). The laparoscopic surgical field then essentially spreads to the foreground, and suture closure of unexpected injuries, including bleeding, should therefore be made from the front and bottom sides, making the best use of the front safety area (Fig. 7G).

Figure 7.

(A) During a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, the specialized retractor shown in this figure ensures adequate retraction/countertraction of the liver without any slippage (blue arrows). Laparosonic coagulating shears serve as a useful scalpel that provides hemostasis for dissection around the inferior vena cava and exposure of the bare area of the liver. To expose the bare area of the liver in pure laparoscopic surgery or a hybrid technique, two working ports should be placed on the lateral-dorsal side and as far to the head side as possible. (B) During a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, rubbing of a bleeding vessel or oozing tissue with a button-shaped electrode with suction and a soft-coagulation system is a key technique for reliable hemostasis. (C) During surgical procedures involving removal of the right lobe in a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, an assistant surgeon should ensure adequate retraction of the liver using two forceps/retractors (blue arrows). (D, E) Under the liver retraction by an assistant during a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery (blue arrows and line), the inferior vena cava wall can be bared by laparosonic coagulating shears (yellow line). The short hepatic veins and hepatocaval ligament can be skeletonized. (F) In hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, the horizontal view from the para-inferior vena cava via a flexible laparoscope provides an excellent view along the inferior vena cava. The inferior vena cava is completely bared in the plain view. This view along the length of the vena cava is an advantageous point for the laparoscope. (G) During a hybrid technique/pure laparoscopic surgery, the laparoscopic surgical field essentially spreads to the foreground (green lines); therefore, a suture for hemostasis should be placed from the front side and from the bottom side (red arrows), using the front safety area. (H) The lateral view via a flexible laparoscope provides an excellent magnified field. The inferior vena cava wall should be bared at the upper side of Spiegel’s lobe after ligation of Arantius’ duct and complete dissection of the connective tissues AD, Arantius’ duct; BAL, bare area of the liver; BSES, button-shaped electrode with suction; HCL, hepatocaval ligament; HSE, hook-shaped electrode; HT, hybrid technique; IVC, inferior vena cava; LCS, laparosonic coagulating shears; LHV, left hepatic vein; MHV, middle hepatic vein; PLS, pure laparoscopic surgery; RAG, right adrenal gland; RHV, right hepatic vein; SHV, short hepatic vein

Discussion

We consider our LAS as an extension of OS [9,12,13,17,18], though HALS is considered an extension of laparoscopic surgery [10]. Essentially, our LAS is an optional extension of OS, making the best use of scopic vision [9,18,21,24]. The concepts of LAS and HALS are distinct from each other [9,10,28]. Although HALS abandons the advantages of PLS or HT [9,23], our LAS benefits LDs. Though it is unrealistic to expect any procedure to have no complications, actual complications greater than grade III according to the Clavien–Dindo classification were not observed in our LAS in live donors.

Liver allografts should be harvested without subtle injuries because even a subtle injury may result in intractable complications in the LDLT recipient [11,18]. Hence, a certain incision is required for graft harvesting, although LDLT surgeons try to minimize this incision [18,21,24]. LAS is advantageous in terms of inducing less damage to the abdominal wall and allowing for faster postoperative recovery [18,21,22,24]. Surprisingly, 30% to 50% of complications in LDs are related to abdominal wall damage and include incisional hernia, bowel obstruction, and chronic discomfort [5]. Moreover, 60% of LDs develop wound-related symptoms, such as a tightened wound, paresthesia, or a hypertrophic scar even at 1 year after OS, and 35% of them continue to have complaints thereafter [18]. In LAS, an upper middle incision is preferable for minimizing abdominal muscle damage [18,21,22,24], and this incision could allow access to all segments [18,21,22,24]. Skillful surgeons have gradually expanded their surgical indications for LDs, in the order of OS, LAS or HT, and PLS [9,18,21,22,30,31]. Subsequently, interestingly enough, they have reported informative results that intentional omission of a transverse or subcostal incision surely benefited patients after surgery, and that unexpected injuries during HT occurred in patients with a questionable omission of midline incision [18,21,22]. We agree that such omission of the midline incision is risky [9,18,21,22], although intentional omission of the transverse or subcostal incision is very beneficial [21,22]. Although a subcostal incision is painful, this incision provides an adequate surgical field [9,18]. It is reasonable that less analgesic action enables a shorter time to hospital discharge and earlier social reintegration [18,21,22]. On the other hand, a scar that is concealable within a bikini line is cosmetically advantageous in some countries with long seashores and nice beaches [5,31]. However, if the skin incision is far from the upper abdomen, one of the advantages of LAS (i.e. direct approach with a flexible laparoscopic vision) is unfortunately lost.

In comparison with our PLS, our LAS can provide a dissectible/cuttable layer with a width that makes it unlikely to suffer injury by the best use of simultaneous use of retraction/countertraction by a hand or finger and marked infiltration of carbon dioxide gas (Fig. 3G,H, 4A, B). Even a lower pressure of pneumoperitoneum is enough to create this layer in LAS. The sufficient width of this layer enables simple cutting by the HSE (Fig. 2E-G, Fig. 3A-D, H, 4C, 5D). Based on this high degree of surgical safety, we intentionally omitted the transverse incision, which is required only for liver removal from the diaphragm [23]. This omission has a great advantage, especially for LDs undergoing RLG, because a longer transverse incision is required in an OS for RLG rather than for LSG [23,33].

For HV hanging in RLG, it is important that bareness of the RHV wall is established and dissection at the RHV/MHV division is performed before creation of pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 1F, G). For HV hanging in LSG, combined use of the laparoscope via an even smaller midline incision is effective. The lateral view via a flexible laparoscope provides an excellent magnified field during PLS, even on the right side from the esophagus (Fig. 7H). Under this view, a direct approach for important procedures involving HV hanging can be performed simply and rapidly (Fig. 5H, 6-D).

Current laparoscopic instruments are well developed, but each instrument should be used in the correct manner [9,34]. Many devices are available, and surgeons should follow the manufacturers’ instructions to avoid any malfunctions [9,34]. Surgeons must also make sure that their knowledge of how to use these devices is regularly updated [34]. In HV reconstruction, a margin of graft HV is important to ensure reliable anastomosis and excellent outflow [35]. The HV margin may be shortened during PLS because the HV will be cut by an endostapler. We employ a specialized device for our LAS [Proximate TX (TX30V), White cartridge (XR30V); Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson], and this device facilitates proper placement of the stapler on the tissue without cutting. This device only closes the side of the donor IVC; it never cuts the graft HV. Hence, the HV margin of the graft is preserved. We cannot apply this device via a laparoscopic port, which is why we make a midline incision in the upper abdomen and why we did not challenge PLS in LDs.

Experience alone is insufficient for achieving safety in laparoscopic surgery [3,34,36]. Preoperative anatomical analysis based on 3D imaging is critical for successful HBP surgeries, including LAS, HT, and PLS (Fig. 1A). Preoperative anatomical analysis also enables both precise evaluation of the liver remnant and graft volume, and efficient planning of the actual operative procedures [19,37], if the surgeons themselves create simulation images [34]. It is reasonable that the graft volume never involves the caudate lobe, because the PV and/or biliary duct branches of the caudate lobe are usually ligated during surgical procedures around the hepatic hilum. Moreover, the SHVs that drain the caudate inflow are also ligated. Although LAS provides an excellent view around the IVC, removal of the whole caudate lobe with ligation of the hepatocaval ligament and all SHVs will require a longer operative time (Fig. 3F, 7E, F). If the graft harvest is delayed, a longer waiting time, which incorporates an anhepatic phase during LDLT, will cause severe problems, including coagulopathy and hemodynamic instability in the LDLT recipient. During LDLT, the donor surgery should proceed without any delay. Thus, preoperative evaluation of the graft volume without the caudate lobe is a realistic way to precisely predict the functional graft volume, a stable course during the recipient surgery, and a smoother process of our LAS.

The required surgical techniques for OS and PLS are completely distinct [1-3,10]. Surgical procedures in PLS should be carefully considered and well established [1,3,9,11,15,16], and we should consider that PLS commonly requires a longer operative time than OS [10]. Some researchers have reported advantageous points of PLS for LDs, such as less blood loss, less pain, a shorter hospital stay, and earlier social reintegration [3,5,6,14]. We also understand that many LDLT surgeons wish to attempt PLS for LDs [1,5,7,9,11,14]. Some LDLT surgeons have actually documented PLS for RLG and LSG [5,7,14]. Advanced devices are dependable (Fig. 6G, H, 7A, B), and flexible laparoscopes provide an excellent magnified view (Fig. 7D-F, H). However, surgeons should become technically familiar with PLS [3,9,38]. A key to this procedure is to expose the bare area of the liver in the right subphrenic area, where two working ports are placed as far as possible toward the lateral-dorsal side (Fig. 1H) and as far as possible toward the head side along the upper midline (Fig. 1B) [38]. The assistant surgeon should adequately retract the liver during the surgical procedure (Fig. 7C, D) to maintain excellent laparoscopic vision along the IVC (Fig. 7E, F). Unexpected bleeding from vessels during donor surgery is a nightmare for surgeons because blood transfusions should be avoided. In OS, a suture placed at the far side of the bleeding point and subsequent grasping of this suture immediately improves this situation. On the other hand, the laparoscopic surgical field essentially spreads to the foreground; therefore, the needle to insert a suture for hemostasis should enter from underneath toward the foreground during PLS (Fig. 7G). In PLS, the rubbing of a bleeding vessel or oozing tissue by a button-shaped electrode with suction with a soft-coagulation system is a key technique for reliable hemostasis (Fig. 7B), since efficient bleeding control is so important in PLS [9]. A self-irrigating monopolar electrode (IO advanced, Erbe) is also useful for hemostasis, especially for sure hemostasis on the cut surface of the liver.

Although there are no definitive studies on optimal drain placement after hepatectomy by PLS, we usually place a closed drain only in the early postoperative period. The bilirubin and amylase levels in the drain discharge may be informative for clinical decisions after PLS. Drains should be placed automatically, and we believe that short-term placement of a drain via a stab wound for the laparoscopic port is not invasive but is effective for the patient’s postoperative course after PLS.

A protracted learning curve under excellent teaching is required for a procurement of prestigious laparoscopic surgeon. Board-certified and well-educated laparoscopic surgeons may employ an HT for LDs without any delay [9,31], and such surgeons in our own institution allow the further stepwise introduction of advanced laparoscopic surgeries [2,3]. Considering the current status of our institution, careful progression from LAS to an HT is our current goal, because we agree that both an HT and HALS can function as a bridge to PLS in the future [10]. Although we are not ready for PLS in LDs [15,16], an HT, which is a combined surgery involving PLS until the preparation for a hanging maneuver and subsequent OS with a direct approach using a laparoscope, seems to be a safe possibility. Where should LDLT surgeons head in the next decade? LDLT surgeons have a very broad intellectual and technical frontier.

Biography

Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Park JI, Kim KH, Lee SG. Laparoscopic living donor hepatectomy: a review of current status. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:779–788. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Briceno J, Wakabayashi G. Comparative short-term benefits of laparoscopic liver resection:9000 cases and climbing. Ann Surg. 2016;263:761–777. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, Geller DA, et al. Recommendations for laparoscopic liver resection: a report from the second international consensus conference held in Morioka. Ann Surg. 2015;261:619–629. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsinberg M, Tellioglu G, Simpfendorfer CH, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic versus open liver tumor resection: a case-controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:847–853. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samstein B, Griesemer A, Cherqui D, et al. Fully laparoscopic left-sided donor hepatectomy is safe and associated with shorter hospital stay and earlier return to work: A comparative study. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:768–773. doi: 10.1002/lt.24116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekheit M, Khafagy PA, Bucur P, et al. Donor safety in live donor laparoscopic liver procurement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3047–3064. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-4045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rotellar F, Pardo F, Benito A, et al. Totally laparoscopic right-lobe hepatectomy for adult living donor liver transplantation: useful strategies to enhance safety. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:3269–3273. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin NC, Nitta H, Wakabayashi G. Laparoscopic major hepatectomy: a systematic literature review and comparison of 3 techniques. Ann Surg. 2013;257:205–213. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827da7fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakabayashi G, Nitta H, Takahara T, Shimazu M, Kitajima M, Sasaki A. Standardization of basic skills for laparoscopic liver surgery towards laparoscopic donor hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasegawa Y, Koffron AJ, Buell JF, Wakabayashi G. Approaches to laparoscopic liver resection: a meta-analysis of the role of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery and the hybrid technique. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:335–341. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soubrane O, de Rougemont O, Kim KH, et al. Laparoscopic living donor left lateral sectionectomy: A new standard practice for donor hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;262:757–761. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Kokudo N. Laparoscopy-assisted hybrid left-side donor hepatectomy: is it truly less invasive for living donors? World J Surg. 2014;38:1560–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marubashi S, Wada H, Kawamoto K, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted hybrid left-side donor hepatectomy: rationale for performing LADH. World J Surg. 2014;38:1562–1563. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scatton O, Katsanos G, Boillot O, et al. Pure laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy in living donors: from innovation to development in France. Ann Surg. 2015;261:506–512. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borle DP, Bharathy KG, Kumar S, Pamecha V. Laparoscopic living donor left hepatectomy: donor safety remains the overriding concern. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:735. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troisi RI. Open or laparoscopic living donor liver hepatectomy: still a challenging operation!Am J Transplant. 2014;14:736. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh KS, Yi NJ, Kim T, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted donor right hepatectomy using a hand port system preserving the middle hepatic vein branches. World J Surg. 2009;33:526–533. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitta H, Sasaki A, Fujita T, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted major liver resections employing a hanging technique: the original procedure. Ann Surg. 2010;251:450–453. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cf87da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohshima S. Volume analyzer SYNAPSE VINCENT for liver analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:235–238. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milsom J, Trencheva K, Monette S, et al. Evaluation of the safety, efficacy, and versatility of a new surgical energy device (THUNDERBEAT) in comparison with Harmonic ACE, LigaSure V, and EnSeal devices in a porcine model. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:378–386. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soyama A, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, et al. Hybrid procedure in living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:679–682. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soyama A, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, et al. Standardized less invasive living donor hemihepatectomy using the hybrid method through a short upper midline incision. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inomata Y, Egawa H. Tanaka K, Inomata Y, Kaihara S, editors. Surgical procedure for right lobectomy. Living-donor liver transplantation. Surgical techniques and innovations. Prous Science:Barcelona. 2003:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eguchi S, Takatsuki M, Soyama A, et al. Elective living donor liver transplantation by hybrid hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery and short upper midline laparotomy. Surgery. 2011;150:1002–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabeshima M, Ogawa K. Tanaka K, Inomata Y, Kaihara S, editors. Modalities for evaluation. Living-donor liver transplantation. Surgical techniques and innovations. Prous Science:Barcelona. 2003:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hori T, Kirino I, Uemoto S. Right posterior segment graft in living donor liver transplantation. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:1076–1082. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujita S, Inomata Y. Tanaka K, Inomata Y, Kaihara S, editors. Surgical procedure for recipient hepatectomy. Living-donor liver transplantation. Surgical techniques and innovations. Prous Science:Barcelona. 2003:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shehata MR, Yagi S, Okamura Y, et al. Pediatric liver transplantation using reduced and hyper-reduced left lateral segment grafts: a 10-year single-center experience. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3406–3413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasahara M, Takada Y, Fujimoto Y, et al. Impact of right lobe with middle hepatic vein graft in living-donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1339–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahara T, Wakabayashi G, Hasegawa Y, Nitta H. Minimally invasive donor hepatectomy: evolution from hybrid to pure laparoscopic techniques. Ann Surg. 2015;261:e3–4. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa Y, Nitta H, Sasaki A, et al. Laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy as a training procedure for surgeons learning laparoscopic hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:525–530. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardinal JS, Reddy SK, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Geller DA. Laparoscopic major hepatectomy: pure laparoscopic approach versus hand-assisted technique. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:114–119. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0553-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueda M, Kozaki K. Tanaka K, Inomata Y, Kaihara S, editors. Surgical procedure for left lateral segmentectomy and left lobectomy. Living-donor liver transplantation. Surgical techniques and innovations. Prous Science:Barcelona. 2003:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hori T, Masui T, Kaido T, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with or without preservation of the spleen for solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:487639. doi: 10.1155/2015/487639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SG. A complete treatment of adult living donor liver transplantation: a review of surgical technique and current challenges to expand indication of patients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:17–38. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallet J, Gayet B, Tsung A, Wakabayashi G, Pessaux P 2nd International Consensus Conference on Laparoscopic Liver Resection Group. Systematic review of the use of pre-operative simulation and navigation for hepatectomy: current status and future perspectives. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:353–362. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikoma N, Itano O, Oshima G, Kitagawa Y. Laparoscopic liver mobilization: tricks of the trade to avoid complications. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:e21–23. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]