Abstract

CKD associates with systemic inflammation, but the underlying cause is unknown. Here, we investigated the involvement of intestinal microbiota. We report that collagen type 4 α3–deficient mice with Alport syndrome–related progressive CKD displayed systemic inflammation, including increased plasma levels of pentraxin-2 and activated antigen–presenting cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells, and Th17– or IFNγ–producing T cells in the spleen as well as regulatory T cell suppression. CKD–related systemic inflammation in these mice associated with intestinal dysbiosis of proteobacterial blooms, translocation of living bacteria across the intestinal barrier into the liver, and increased serum levels of bacterial endotoxin. Uremia did not affect secretory IgA release into the ileum lumen or mucosal leukocyte subsets. To test for causation between dysbiosis and systemic inflammation in CKD, we eradicated facultative anaerobic microbiota with antibiotics. This eradication prevented bacterial translocation, significantly reduced serum endotoxin levels, and fully reversed all markers of systemic inflammation to the level of nonuremic controls. Therefore, we conclude that uremia associates with intestinal dysbiosis, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and bacterial translocation, which trigger the state of persistent systemic inflammation in CKD. Uremic dysbiosis and intestinal barrier dysfunction may be novel therapeutic targets for intervention to suppress CKD–related systemic inflammation and its consequences.

Keywords: inflammation, chronic kidney disease, microbiota

CKD is associated with persistent systemic inflammation driving endothelial dysfunction, atherogenesis, and cardiovascular disease,1 but the underlying cause for CKD–related systemic inflammation is still unclear. It was thought that dialysis–related catheter infections, contaminated water, or nonbiocompatible tubes and dialysis filters account for this phenomenon. However, serum levels of circulating bacterial endotoxin increase from CKD stage 2 to stage 5,2 which implies an endogenous source of bacterial endotoxin. Here, we focus on the body’s microbiota as a potential causative trigger for CKD–related systemic inflammation.

The microbiota represents 10 times more bacterial cells than human cells residing on the outer and inner surfaces of the body.3 Symbionts limit the growth of pathobionts and dysbiosis.4 Intestinal symbionts produce essential nutrients, such as vitamin K and components that regulate numerous metabolic processes inside the body.5 Studies with germfree mice revealed that the microbiota builds and educates the immune system early in life.6 However, epithelial barriers must keep the microbiota outside the body to avoid bacterial translocation, systemic inflammation, and fatal infections.7,8 Dysbiosis, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and bacterial translocation are well described to cause and perpetuate inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease,9 portal hypertension,7 or heart failure.10 Hence, we hypothesized that the metabolic changes during uremia foster intestinal dysbiosis and bacterial translocation as a trigger for the persistent state of CKD–related systemic inflammation in a similar manner.

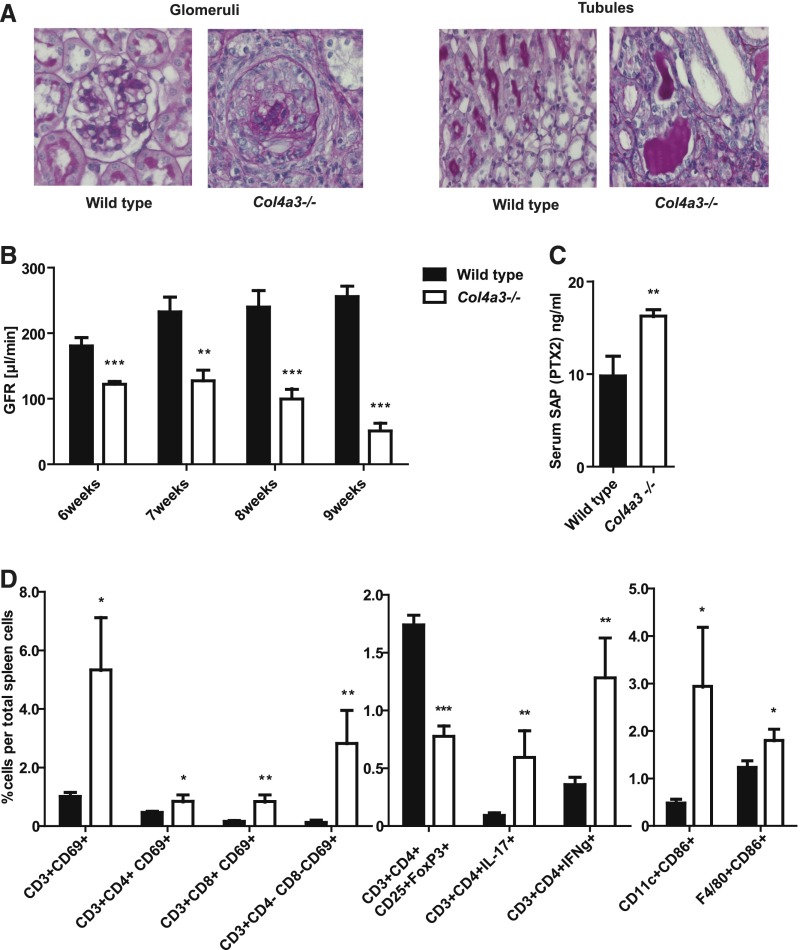

We selected collagen type 4 α3 (Col4a3) –deficient mice to address our hypothesis, because these mice spontaneously develop progressive glomerulosclerosis and CKD (Alport nephropathy) without requiring any surgical, toxic, or dietary interventions that could affect the microbiota beyond the metabolic changes of uremia (Figure 1, A and B).11 Uremia in 9-week-old Col4a3-deficient mice was associated with serum levels of pentraxin-2/serum amyloid P component, which is the functional murine homolog of human C–reactive protein that serves as a marker of systemic inflammation in mice (Figure 1C). In addition, we analyzed splenocyte phenotyping at week 9, because the spleen removes blood-borne antigens and initiates innate and adaptive immune responses against pathogens. Flow cytometry revealed that uremia in Col4a3-deficient mice was associated with increased numbers of activated CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes (activation marker CD69) and IL-17– or IFNγ–producing CD4 T cells (Figure 1D). In contrast, the numbers of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells were reduced compared with in nonuremic control mice (Figure 1D). Also, the population of activated (CD86+) CD11c+ antigen–presenting cells was enlarged (Figure 1D), implying a general state of systemic immune activation in uremic Col4a3–deficient mice.

Figure 1.

Systemic inflammation in uremic Col4a3–deficient mice. (A) Glomerular and tubulointerstitial pathology in 9-week-old Col4a3-deficient mice is illustrated by periodic acid–Schiff staining. Representative images are shown at an original magnification of ×400. (B) CKD is illustrated by progressive decline in GFR measured by transcutaneous FITC Sinistrin clearance in conscious mice. (C) Serum levels of pentraxin-2 (PTX2)/serum amyloid P (SAP) are the murine equivalent to human PTX1/C-reactive protein and indicate systemic inflammation at 9 weeks of age. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocytes and myeloid cells in spleens of 9-week-old nonuremic wild–type and uremic Col4a3–deficient mice shows significant increased numbers of activated T cells and CD11c+ myeloid mononuclear phagocytes. Data represent means±SEMs of at least five mice in each group. *P<0.05 versus wild type; **P<0.01 versus wild type; ***P<0.001 versus wild type.

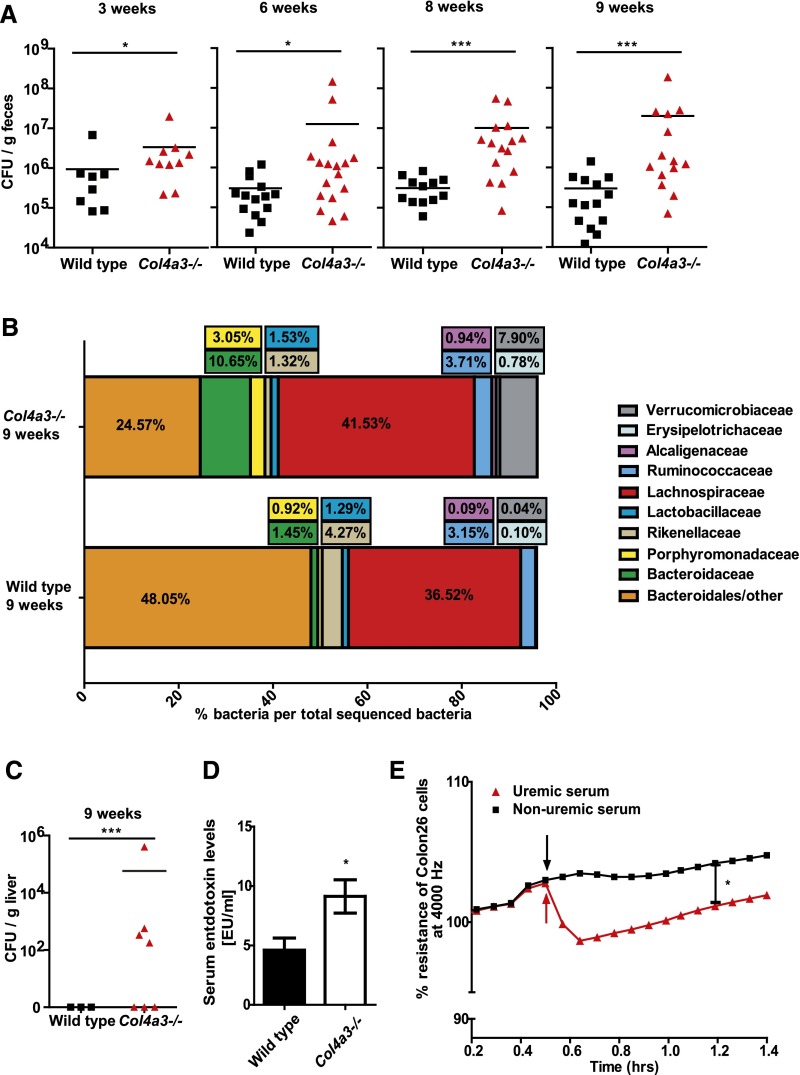

Speculating that systemic inflammation in uremia is related to changes in the intestinal microbiota, we first characterized the intestinal microbiota in Col4a3-deficient and wild-type mice in a quantitative and qualitative manner. Although we found average facultative anaerobic bacterial count of 105–106 CFU/g feces in wild-type mice from 3–9 weeks of age, the progressive CKD of Col4a3-deficient mice was associated with an increase in facultative anaerobic bacterial numbers by five- to 10-fold compared with age–matched wild–type mice (Figure 2A). Amplicon sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes was performed to characterize the fecal microbiota composition in 3- and 9-week-old uremic and nonuremic mice. α-Diversity, a measure for microbiota complexity, was slightly but not significantly increased in 9-week-old mice, which is in line with an increase in species richness with age. Likewise, no significant difference was found between wild-type and Col4a3-deficient mice (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). β-Diversity, a similarity score between different microbial populations, was determined by analysis of unweighted and weighted UniFrac distance matrices. Unweighted UniFrac distances compare microbial communities within a phylogenetic context on the basis of the presence or absence of taxa (community membership), whereas weighted UniFrac also incorporates relative abundance information (community structure). Significant differences were determined only by unweighted UniFrac between wild-type and Col4a3-deficient mice at 9 weeks of age and between wild-type mice at 9 weeks of age and Col4a3-deficient mice at 3 weeks of age (Supplemental Figure 3). Specifically, at 9 weeks of age, the relative abundance of Alcaligenaceae β-Proteobacteria (mean±SEM) was 0.09%±0.03% to 0.94%±0.42% (P>0.50), the relative abundance of Verrucomicrobiaceae (mean±SEM) was 0.04%±0.01% to 7.90%±6.95% (P>0.50), the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes-Bacteroidaceae (mean±SEM) was 1.45%±0.72% to 10.65%±3.72% (P<0.50), and the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes-Porphyromonadaceae (mean±SEM) was 0.92%±0.25% to 3.05%±1.05% (P>0.50) in Col4a3–deficient uremic mice, whereas Bacteroidetes-Bacteroirales were reduced in uremic mice (48.05%±7.97% to 24.57%±10.46%; P<0.001) (Figure 2B). Uremia-related dysbiosis was not associated with any changes in small intestinal wall immune cell subtypes or the release of secretory (s)IgA (Table 1). Hence, we conclude that progressive CKD and its accompanying uremia in Col4a3-deficient mice are associated with proteobacterial blooms and dysbiosis.

Figure 2.

Uremia affects microbiota diversity and intestinal barrier function. (A) Quantitative dysbiosis, measured in number of CFUs per gram of feces, is seen in Col4a3-deficient mice compared with wild-type animals. With increasing age, Col4a3-deficient mice developed an even more significant quantitative dysbiosis. (B) Relative abundance of different bacterial taxa detected in fecal samples. Alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota, which may be accounted for by aging, are detectable in 3- versus 9-week-old mice in both strains. Comparison of Col4a3-deficient and wild-type mice at an age of 9 weeks old depicts differences in the orders of Bacteroidales, Burholderiales (family of Alcaligenaceae), Enterobacteriales, and Verrucomicrobiales. Detailed information, including statistics, is listed in Supplemental Table 1. (C) Bacterial colonies grew from liver tissue of uremic Col4a3–deficient mice but not from nonuremic wild–type mice. (D) Sera of uremic and nonuremic mice were analyzed using limulus amebocyte lysate assay and showed significantly elevated levels of bacterial endotoxin. (E) ECIS experiments display a significant reduction for mean resistance across single-cell layers of Colon26 cells after treatment with serum of uremic Col4a3–deficient mice (time point marked by arrows) compared with cells treated with serum of wild-type mice. Data represent means±SEMs of at least five mice in each group. *P<0.05 versus wild type; ***P<0.001 versus wild type.

Table 1.

Gut leukocyte flow cytometry in 8.5-week-old Col4a3-deficient mice

| Cell Type | Wild Type (Small Intestine) | Col4a3 Deficient (Small Intestine) |

|---|---|---|

| CD11c+/CD86+ | 0.3±0.1 | 0.2±0.0 |

| F4/80+/CD86+ | 0.4±0.1 | 0.3±0.0 |

| CD3+/CD69+ | 3.1±0.9 | 3.8±1.3 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD69+ | 1.2±0.4 | 0.9±0.3 |

| CD3+/CD8+/CD69+ | 0.5±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 |

| CD3+/CD4−/CD8−/CD69+ | 1.1±0.4 | 2.1±0.9 |

| CD3+/CD4+/IFNγ−/IL-17+ | 0.4±0.1 | 0.1±0.0 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ | 0.3±0.1 | 0.3±0.1 |

Means are given in percentage terms ±SEM (n=5).

Dysbiosis itself may affect metabolic processes or bowel homeostasis, but some barrier dysfunction and bacterial (product) translocation would seem mandatory to explain the systemic immune activation noted in uremic mice. In fact, liver cultures revealed an infestation with culturable live bacteria in 60% of all uremic Col4a3–deficient mice (Figure 2C), which was associated with a trend toward more activated macrophages and dendritic cells in livers (Table 2). Hence, we orally challenged uremic mice with commensal Escherichia coli constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) by oral gavage. We retrieved GFP+ bacteria in 40% of livers of uremic mice but none from the nonuremic mice (not shown), which documents translocation of even living bacteria from the intestinal tract. Consistent with these findings, uremic Col4a3–deficient mice displayed significantly increased serum levels of bacterial endotoxin compared with nonuremic wild–type mice (Figure 2D). A careful analysis of the intestinal wall by periodic acid–Schiff staining, ZO-1 immunostaining, and transmission electron microscopy did not reveal structural alterations, such as ulcers or diffuse tight junction abnormalities, in wild-type and Col4a3-deficient mice (Supplemental Figure 4). However, when cultured colon-epithelial cells were exposed to serum from either uremic Col4a3–deficient or nonuremic wild–type mice, only uremic serum reduced the transepithelial resistance as a marker of transepithelial permeability (Figure 2E).

Table 2.

Gut leukocyte flow cytometry in 8.5-week-old Col4a3-deficient mice with and without antibiotic treatment

| Cell Type | Col4a3 Deficient without Antibiotic Treatment (Small Intestine) | Col4a3 Deficient with Antibiotic Treatment (Small Intestine) |

|---|---|---|

| CD11c+/CD86+ | 0.2±0.0 | 0.5±0.2 |

| F4/80+/CD86+ | 0.3±0.0 | 0.6±0.3 |

| CD3+/CD69+ | 3.8±1.3 | 6.1±3.6 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD69+ | 0.9±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 |

| CD3+/CD8+/CD69+ | 0.5±0.1 | 0.6±0.2 |

| CD3+/CD4−/CD8−/CD69+ | 2.1±0.9 | 4.1±3.0 |

| CD3+/CD4+/IFNγ−/IL-17+ | 0.1±0.0 | 0.3±0.1 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ | 0.3±0.1 | 0.4±0.1 |

Means are given in percentage terms ±SEM (n=5).

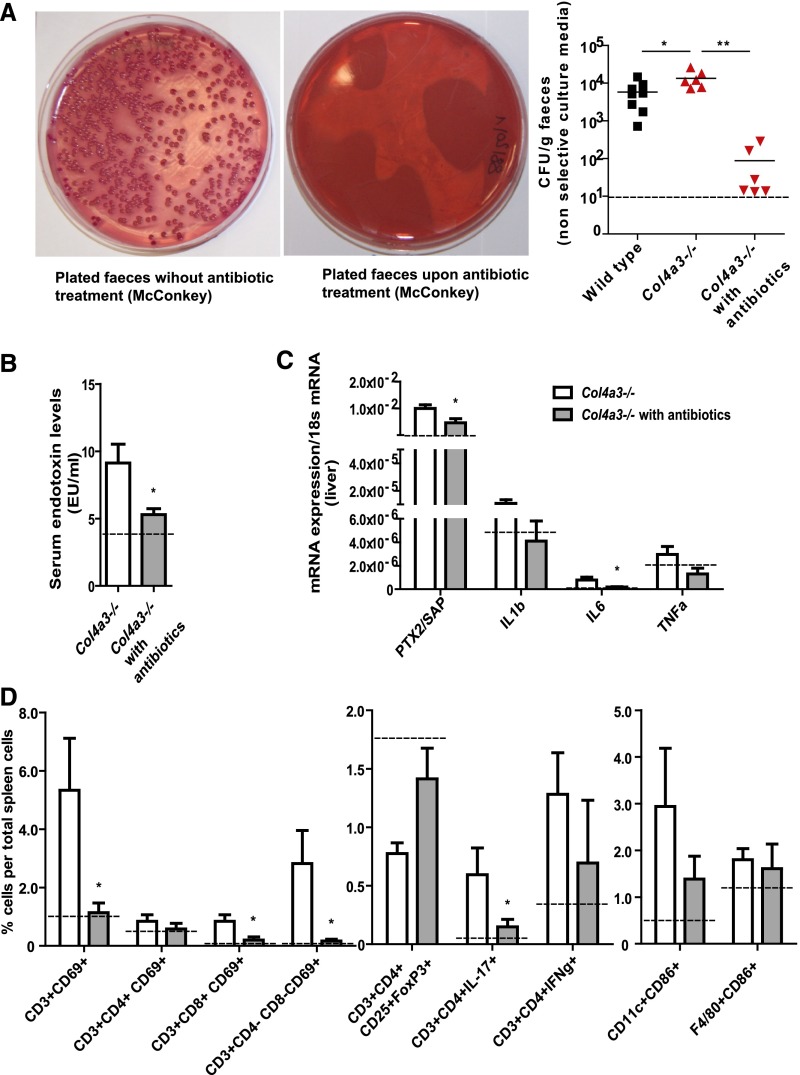

To test for a causal relationship between uremic dysbiosis–related intestinal translocation of bacteria and systemic inflammation, we treated Col4a3-deficient mice with a synergistic oral combination of antibiotic drugs, which eradicated the facultative anaerobic intestinal microbiota from gut and liver (Figure 3A). Microbiota depletion significantly reduced the serum levels of bacterial endotoxin (Figure 3B) and the intrahepatic mRNA expression levels of pentraxin-2/serum amyloid P and IL-6 (Figure 3C). Consistently, flow cytometry of splenocytes displayed less activated T cells and a recovery of regulatory T cells (Figure 3D). No effect on renal function or intrarenal leukocyte profiles was detected (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that uremic dysbiosis and bacterial translocation cause CKD–related systemic inflammation.

Figure 3.

Uremic systemic inflammation is corrected by eradication of the microbiota. All dashed lines in B and C represent values of control wild–type animals. (A) Representative pictures show a complete eradication of Gram–negative fecal flora after antibiotic treatment. The dot blot graph illustrates CFUs of feces cultures at an age of 7 weeks old. The graph depicts results of nonselective media, because a detection limit (dashed line) of 10 CFU/g feces was taken. (B) Serum endotoxin levels with and without antibiotic treatment in Col4a3-deficient mice. (C) Acute–phase protein serum amyloid P and IL-6 mRNA expression levels with and without antibiotic treatment in Col4a3-deficient mice. (D) Flow cytometry of spleen cell suspensions from uremic Col4a3–deficient mice with and without antibiotic treatment. Data represent means±SEMs of at least five mice in each group. *P<0.05 versus wild type; **P<0.01 versus wild type.

Bacterial endotoxin is an important stimulus for immune activation via Toll–like receptor 4 and caspase 11 in Gram-negative sepsis with or without kidney failure.12,13 The different stages of CKD and CKD–related systemic inflammation are associated with a progressive increase in circulating bacterial endotoxin, CD14, and other biomarkers of systemic inflammation.2,14,15 Also, urea secreted by the uremic organism into the gut lumen promotes urease-forming bacteria that was seen already in humans and similar to our findings.16,17 Some phyla of the urase-forming bacteria are also involved in the production of so–called uremic toxins, like indole or p-cresole, both known to promote systemic inflammation. In principle, causality of this association could be both ways (e.g., CKD-related inflammation may promote endotoxin entry or CKD–related uremic toxin/endotoxin entry may promote inflammation). Our study now documents that the CKD–related systemic immune activation is reversible on eradicating the microbiota. This implies that it is the microbiota that accounts for CKD–related systemic inflammation.

Systemic administration of antibiotics affects microbiota from all over the body, and therefore, it remains uncertain which microbiota from which areas contribute most to CKD-related inflammation. However, the gut contains, by far, the largest number of bacterial cells, and we also show by using GFP–labeled E. coli that translocation of bacteria across the intestinal barrier occurs in CKD. In uremic mice, even living bacteria reached the liver, probably by crossing the intestinal epithelial barrier into the portal vein. How this translocation can occur is not entirely clear. Adenine–rich diet–induced CKD in rats was reported to be associated with diffuse tight junction disintegration in intestinal epithelial cells.18–20 Because Col4a3-deficient mice with spontaneous CKD lacked this phenomenon, it may be possible that such changes relate to adenine crystal–induced epithelial cytotoxicity rather than to uremia per se. In fact, crystals can have direct cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells.21 Nevertheless, we and others found uremic (but not nonuremic) plasma to increase the permeability of intestinal epithelial cell monolayers in vitro.18 Hence, as a working hypothesis, at least focal intestinal barrier dysfunction should promote bacterial translocation, and potentially, the intestinal dysbiosis comes as a cofactor.

The CKD-related increase in intestinal proteobacteria represents a shift to potentially pathogenic bacteria (pathobionts) that is frequently associated with a broad spectrum of diseases.22 Our findings are in line with several previous studies in humans with uremia,16 uremic rats,16 and uremic mice.23 Intestinal dysbiosis is associated with a shift in the microbiota’s secretory profile, including factors like the phosphatidylcholine metabolite trimethylamine N–oxide that may directly drive CKD progression and cardiovascular disease.24,25 The microbiota is known to be sensitive to diet– or metabolism–related ecosystem changes.26,27 The metabolic alterations of uremia, including metabolic acidosis and azotemia, generate numerous explanations for microbiota shifts.26,27 Attempts to correct uremic dysbiosis with probiotic formulations are on the basis of the idea to modulate uremic dysbiosis with targeted interventions.28 Together, we conclude that intestinal dysbiosis, barrier dysfunction, and bacterial translocation account for systemic inflammation in CKD and are potentially fully reversible.

Concise Methods

Animal Studies

Col4a3–deficient and wild–type littermate mice in identical Sv129 genetic backgrounds were bred under specific pathogen–free housing conditions, cohoused in same cages, and genotyped as described earlier.29 At the age of 6 weeks old, groups of Col4a3-deficient and wild-type mice were randomized to oral gavage of 25 mg/kg neomycin, 60 mg/kg ampicillin, or 25 mg/kg metronidazole once per day over a period of 12 days. In some mice, E. coli strain MG1655 harboring plasmid pM979 for constitutive GFP expression was administered by oral gavage on day 13.30 Organs (kidney, liver, and spleen) were harvested under sterile conditions before preparing ileum and colon. All animal studies were approved by the local governmental ethics committee.

GFR and Bioassays

GFR was measured in conscious mice using a transcutaneous detector system for FITC Sinistrin clearance kinetics (Mannheim Pharma & Diagnostics GmbH) as described.31 Cardiac puncture was performed under sterile conditions, and limulus amebocyte lysate assay was used to quantify plasma LPS levels (HIT302; Hycult Biotech, PB Uden, The Netherlands). Serum amyloid P levels were detected by the commercial Mouse Pentraxin 2/SAP Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Bacterial Quantification and Qualification

CFU Counts

Fresh feces were dissolved in 500 μl PBS, diluted, and plated at a volume of 50 μl on MacConkey agar plates as a selective medium for Gram bacteria and LB agar plates as a nonselective medium. Plates were incubated for 1–2 days at 37°C aerobically; 2–3 g organ tissue was dissected under sterile conditions by straining though a sterile sieve of 70-μm mesh width and rinsed thoroughly with 500 μl PBS, and 100 μl were plated on MacConkey agar plates. To quantify ampicillin–resistant E. coli MG1655 pM979, we used agar containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). All CFU counts were calculated per weight of the inserted stool or tissue specimen at a detection limit of 10 CFU/g for feces and 60 CFU/g for liver.

Stool DNA Isolation and 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (51504; Qiagen, Germantown, MD) was used to extract gDNA from freshly collected feces samples from both mouse strains. The 16S rRNA gene variable regions V3–V6 were amplified by PCR using fecal gDNA. PCR comprised two consecutive steps. Primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene (italic) and specific primers carrying the 5′M13/rM13 adapters (bold) 338F-M13 (GTAAACGACGGCCAGTGCTCCTACGGGWGGCAGCAGT) and 1044R-rM13 (GGAAACAGCTATGACCATGACTACGCGCTGACGACARCCATG) were used to amplify the V3–V6 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. One PCR reaction contained 500 nM each primer (338F-M13 and 1044R-rM13), 2× DreamTaq PCR Master Mix, and 50 ng template gDNA. PCR reaction was performed in duplicates using a peqSTAR 2× Gradient Thermocycler (Peqlab Biotechnology). PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 20 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds and a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 minutes. Duplicate reactions were pooled and loaded on a 1% agarose gel to confirm successful PCR amplification. After purification of PCR products using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-Up Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions, concentration and quality of the purified PCR products were assessed using Nanodrop (Peqlab Biotechnology). To barcode each PCR product with a specific MID sequence and add the 454–specific Lib-L tag, a second PCR was performed using M13/rM13-specific primers containing the 454–specific Lib-L primers (underlined) A-M13 (CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG/MIDsequence/GTAAACGACGGCCAGG) and B-rM13 (CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAGGGAAACAGCTATGA CCATGA). The 40 different MID 10-bp error–correcting barcodes for multiplexing are listed in Table 3. PCR was performed using 400 nM each primer (A-M13 and B-rM13). Amplicons of the second PCR were pooled and purified by ethanol precipitation. Purified PCR products were run on a 0.8% agarose gel, bands corresponding to the barcoded 16S rRNA gene sequences were excised, and DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-Up Kit. DNA was eluted in ddH2O, further purified using AMPure Beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA), and finally, resuspended in ddH2O. Concentration and quality of the purified barcoded sequences were assessed using a Nanodrop (Peqlab Biotechnology). Samples were stored at −20°C. Amplicon sequencing was performed at Eurofins on a 454 GS FLX Titanium Platform from one side (Lib-L-A) according to the recommended procedures for 454 Roche (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Table 3.

MID barcodes for 454 multiplexing

| Designation | MID Sequence |

|---|---|

| MID1 | ACGAGTGCGT |

| MID2 | ACGCTCGACA |

| MID3 | AGACGCACTC |

| MID4 | AGCACTGTAG |

| MID5 | ATCAGACACG |

| MID6 | ATATCGCGAG |

| MID7 | CGTGTCTCTA |

| MID8 | CTCGCGTGTC |

| MID9 | TAGTATCAGC |

| MID10 | TCTCTATGCG |

| MID11 | TGATACGTCT |

| MID12 | TACTGAGCTA |

| MID13 | CATAGTAGTG |

| MID14 | CGAGAGATAC |

| MID15 | ATACGACGTA |

| MID16 | TCACGTACTA |

| MID17 | TCGATCGAGT |

| MID18 | CAGTCAGTAG |

| MID19 | ACACTGACAC |

| MID20 | GTACGATCGT |

| MID21 | TGCGTGAGCA |

| MID22 | ACAGCTCGCA |

| MID23 | CTCACGCAGA |

| MID24 | GATGTCACGA |

| MID25 | GCACAGACTA |

| MID26 | GAGCGCTATA |

| MID27 | ATCTCTGTGC |

| MID28 | CTGTGCGCTC |

| MID29 | CGACTATGAT |

| MID30 | GCGTATCTCT |

| MID31 | TCTGCATAGT |

| MID32 | ATCGAGTCAT |

| MID33 | GTGATGATAC |

| MID34 | CATAGAGAGC |

| MID35 | ATGCAGCATA |

| MID36 | ATCATGCACT |

| MID37 | TGAGCTAGCT |

| MID38 | GATGACTGAC |

| MID39 | CACAGTCACA |

| MID40 | TGCTAGCATG |

MID, manufacturer identification code.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Data were analyzed as described recently.32 Briefly, raw sequences were preprocessed using the FASTX-Toolkit and UCHIME. Sequences that passed quality filtering (minimum quality of 20) were demultiplexed and trimmed to delete short reads (minimum length of 100). Sequences were checked for chimeras (UCHIME; standard parameters) using the microbiomeutils (r20110519) reference database. A self-written script produced a mapping file and a fastA file that were used as input for Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME).

Processing

Sequences were analyzed using the package QIIME. Sequences were assigned to operational taxonomic units with uclust at 97% pairwise identity and then, classified taxonomically using the RDP classifier. The charts show the relative abundance of taxa at phylum level in the datasets (mean±SEM; n=5). A representative set of sequences was aligned using PyNAST. The alignment was used to build a phylogenetic tree with FastTree. The tree was used to calculate UniFrac distances between samples.33 PERMANOVA34 was used to test for statistical significance of sample groupings on the basis of different UniFrac distance matrices. For α-diversity measurements, rarefaction analysis was performed for the estimated number of species in each sample using the observed species algorithm in QIIME.

Tissue Evaluation

Parts of kidney, ileum, and colon were fixed in 10% formalin in PBS and embedded in paraffin; 4-μm sections were stained with periodic acid–Schiff reagent. For ultrastructural analysis, colonic specimens of 8-week-old treated and untreated mice were dissected and fixed in 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde. Polymerization (using fresh Epon resin) was carried out at 60°C for 24 hours as described.35 The following antibodies were used as primary antibodies for immunostaining: goat anti–ZO-1 and rabbit antioccludin (ab190085 and ab64482, respectively; Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA).

Real–Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNA Extraction Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and RNA quality was assessed using agarose gels. After isolation of RNA, cDNA was generated using reverse transcription (Superscript II; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). An SYBR Green Dye Detection System was used for quantitative real–time PCR on Light Cycler 480 (Roche) using 18s rRNA as a housekeeping gene. Gene-specific primers blasted with ensemble-BLAST and NCBI primer-BLAST (Metabion, Martinsried, Germany) were used as listed in Table 4. Nontemplate controls consisting of all used reagents were negative for target and housekeeping genes. To reduce the risk of false–positive crossing points, the high confidence algorithm was used. The melting curves profiles were analyzed for every sample to detect eventual unspecific products or primer dimers. As a housekeeping gene, 18s RNA was used.

Table 4.

Primers used for real–time quantitative RT-PCR

| Gene Target | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| IL-6 | |

| Forward | 5′-TGATGCACTTGCAGAAAACA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACCAGAGGAAATTTTCAATAGGC-3′ |

| TNFα | |

| Forward | 5′-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT-3′ |

| IL-1β | |

| Forward | 5′-CACTGTCAAAAGGTGGCATTT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTCCTTGTGCAAGTGTCTGAAG-3′ |

| Pentraxin-2/serum amyloid P | |

| Forward | 5′-AGCTGCTGCTGTCATACCCT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CAGATTCTCTGGGGAACACAA-3′ |

Isolation and Flow Cytometry of Organ Leukocytes and Stimulated T Cells

Spleen, liver, and small intestine single–cell suspensions were prepared and stained for flow cytometry using the following antibodies: anti-CD3ε (clone 145–2C11; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA), anti-CD4 (clone RM4–5; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.7; Becton Dickinson), anti-CD69 (clone H1.2F3; Becton Dickinson), anti-FOXP3 (421403; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), anti-CD11c (clone HL3; Becton Dickinson), anti-F4/80 (clone MCA; AbD Serotec), anti-CD86 (clone GL1; Becton Dickinson), and anti–IL-17 (ebio17B7; Becton Dickinson). Intracellular staining for FoxP3 and IL-17 was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (Becton Dickinson). T cell stimulation assay was done on spleen cells (app. 106) in 200 μl PBS buffer; 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate and 1 μg/ml inomycin were added and incubated at 37°C for 4.5 hours before staining occurred.

In Vitro Studies

Uremic serum–induced changes in resistance and capacitance of immortal murine colon-26 cells (Lot 400156–812; CLS, Eppelheim, Germany) were analyzed using an Electric Cell Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) Device (Applied Biophysics Inc., New York, NY). Cells were cultured in RPMI Glutamax (Life Sciences, Heidelberg, Germany) plus 10% dialyzed FCS (Life Sciences Heidelberg, Germany) before seeding. Therefore, 1.0×106 frozen cells (in 1.0 ml cryomedia and 10% DMSO in dialyzed FCS) were thawed and recultured in the mentioned media until confluency. First, for ECIS measurement, the wells off the experimental chamber were precoated for 10 minutes with cysteine. Second, another coating with 0.01% collagen (type 1 calf skin) was done overnight at 4°C. Cells from the same passage were seeded with a density of 600,000 cells per well in a volume of 400 μl media and incubated overnight (37°C and 5% CO2). Medium was removed the next day, and 360 μl fresh medium was added carefully. The prepared chamber was plugged to the ECIS device (multichannel mode) for 1 hour without any manipulation. Subsequently, a frequency check was done followed by another 1 hour in multichannel mode. Wells without changes concerning resistance were taken for stimulation. The confluent monolayers were stimulated with 40 μl serum of either wild–type Sv129 mice (BUN=24 mg/dl) or Col4a3-deficient mice (BUN=240 mg/dl). After stimulation, resistance was recorded for approximately 18 hours. The starting point of the timeline (Figure 2E) was set to a time point where an almost constant slope of the resistance curves was achieved.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as means±SEMs. Comparison of single groups was performed using t or Mann–Whitney U tests. Normal distribution was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Multiple groups were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. PERMANOVA on unweighted and weighted UniFrac distance matrices was performed in QIIME.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan Draganovic, Jana Mandelbaum, and Mauel Diekl for expert technical assistance.

This project was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Munich. Parts of this project were prepared as a doctoral thesis at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Munich by M.S.K.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015111285/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Carrero JJ, Stenvinkel P: Inflammation in end-stage renal disease--what have we learned in 10 years? Semin Dial 23: 498–509, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre CW, Harrison LE, Eldehni MT, Jefferies HJ, Szeto CC, John SG, Sigrist MK, Burton JO, Hothi D, Korsheed S, Owen PJ, Lai KB, Li PK: Circulating endotoxemia: A novel factor in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 133–141, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R: Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489: 220–230, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buffie CG, Pamer EG: Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 790–801, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara AM, Shanahan F: The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep 7: 688–693, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT: Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature 489: 231–241, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz P, Nischalke HD, Strassburg CP, Spengler U: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: The clinical challenge of a leaky gut and a cirrhotic liver. World J Hepatol 7: 304–314, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sertaridou E, Papaioannou V, Kolios G, Pneumatikos I: Gut failure in critical care: Old school versus new school. Ann Gastroenterol 28: 309–322, 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maloy KJ, Powrie F: Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 474: 298–306, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Steels P, Grieten L, Malbrain M, Tang WH, Mullens W: Abdominal contributions to cardiorenal dysfunction in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 485–495, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosgrove D, Meehan DT, Grunkemeyer JA, Kornak JM, Sayers R, Hunter WJ, Samuelson GC: Collagen COL4A3 knockout: A mouse model for autosomal Alport syndrome. Genes Dev 10: 2981–2992, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B: Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: Mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282: 2085–2088, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kayagaki N, Wong MT, Stowe IB, Ramani SR, Gonzalez LC, Akashi-Takamura S, Miyake K, Zhang J, Lee WP, Muszyński A, Forsberg LS, Carlson RW, Dixit VM: Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science 341: 1246–1249, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, Devaney J, Wing MR, Reilly M, Shah VO, Balakrishnan VS, Guzman NJ, Girndt M, Periera BG, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Joffe MM, Raj DS CRIC Study Investigators : Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1938–1946, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poesen R, Ramezani A, Claes K, Augustijns P, Kuypers D, Barrows IR, Muralidharan J, Evenepoel P, Meijers B, Raj DS: Associations of soluble CD14 and endotoxin with mortality, cardiovascular disease, and progression of kidney disease among patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1525–1533, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaziri ND, Wong J, Pahl M, Piceno YM, Yuan J, DeSantis TZ, Ni Z, Nguyen TH, Andersen GL: Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int 83: 308–315, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong J, Piceno YM, Desantis TZ, Pahl M, Andersen GL, Vaziri ND: Expansion of urease- and uricase-containing, indole- and p-cresol-forming and contraction of short-chain fatty acid-producing intestinal microbiota in ESRD. Am J Nephrol 39: 230–237, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaziri ND, Goshtasbi N, Yuan J, Jellbauer S, Moradi H, Raffatellu M, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Uremic plasma impairs barrier function and depletes the tight junction protein constituents of intestinal epithelium. Am J Nephrol 36: 438–443, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaziri ND, Yuan J, Khazaeli M, Masuda Y, Ichii H, Liu S: Oral activated charcoal adsorbent (AST-120) ameliorates chronic kidney disease-induced intestinal epithelial barrier disruption. Am J Nephrol 37: 518–525, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaziri ND, Yuan J, Rahimi A, Ni Z, Said H, Subramanian VS: Disintegration of colonic epithelial tight junction in uremia: A likely cause of CKD-associated inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2686–2693, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulay SR, Desai J, Kumar SV, Eberhard JN, Thomasova D, Romoli S, Grigorescu M, Kulkarni OP, Popper B, Vielhauer V, Zuchtriegel G, Reichel C, Bräsen JH, Romagnani P, Bilyy R, Munoz LE, Herrmann M, Liapis H, Krautwald S, Linkermann A, Anders HJ: Cytotoxicity of crystals involves RIPK3-MLKL-mediated necroptosis. Nat Commun 7: 10274, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter SE, Bäumler AJ: Why related bacterial species bloom simultaneously in the gut: Principles underlying the ‘Like will to like’ concept. Cell Microbiol 16: 179–184, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishima E, Fukuda S, Shima H, Hirayama A, Akiyama Y, Takeuchi Y, Fukuda NN, Suzuki T, Suzuki C, Yuri A, Kikuchi K, Tomioka Y, Ito S, Soga T, Abe T: Alteration of the intestinal environment by lubiprostone is associated with amelioration of adenine-induced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1787–1794, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amery-Gale J, Vaz PK, Whiteley P, Tatarczuch L, Taggart DA, Charles JA, Schultz D, Ficorilli NP, Devlin JM, Wilks CR: Detection and identification of a gammaherpesvirus in Antechinus spp. in Australia. J Wildl Dis 50: 334–339, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL: Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 368: 1575–1584, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anders HJ, Andersen K, Stecher B: The intestinal microbiota, a leaky gut, and abnormal immunity in kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 1010–1016, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramezani A, Raj DS: The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 657–670, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koppe L, Mafra D, Fouque D: Probiotics and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 88: 958–966, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryu M, Kulkarni OP, Radomska E, Miosge N, Gross O, Anders HJ: Bacterial CpG-DNA accelerates Alport glomerulosclerosis by inducing an M1 macrophage phenotype and tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated podocyte loss. Kidney Int 79: 189–198, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stecher B, Hapfelmeier S, Müller C, Kremer M, Stallmach T, Hardt WD: Flagella and chemotaxis are required for efficient induction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis in streptomycin-pretreated mice. Infect Immun 72: 4138–4150, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber A, Shulhevich Y, Geraci S, Hesser J, Stsepankou D, Neudecker S, Koenig S, Heinrich R, Hoecklin F, Pill J, Friedemann J, Schweda F, Gretz N, Schock-Kusch D: Transcutaneous measurement of renal function in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F783–F788, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gronbach K, Flade I, Holst O, Lindner B, Ruscheweyh HJ, Wittmann A, Menz S, Schwiertz A, Adam P, Stecher B, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S, Gruber AD, Kulik A, Huson D, Autenrieth IB, Frick JS: Endotoxicity of lipopolysaccharide as a determinant of T-cell-mediated colitis induction in mice. Gastroenterology 146: 765–775, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozupone C, Lladser ME, Knights D, Stombaugh J, Knight R: UniFrac: An effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J 5: 169–172, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McArdle B: Fitting multivariate models to community data: A comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82: 290–297, 2001. 22997256 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darisipudi MN, Thomasova D, Mulay SR, Brech D, Noessner E, Liapis H, Anders HJ: Uromodulin triggers IL-1β-dependent innate immunity via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1783–1789, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.