Abstract

The tight junction (TJ) has a key role in regulating paracellular permeability to water and solutes in the kidney. However, the functional role of the TJ in the glomerular podocyte is unclear. In diabetic nephropathy, the gene expression of claudins, in particular claudin-1, is markedly upregulated in the podocyte, accompanied by a tighter filtration slit and the appearance of TJ-like structures between the foot processes. However, there is no definitive evidence to show slit diaphragm (SD) to TJ transition in vivo. Here, we report the generation of a claudin-1 transgenic mouse model with doxycycline-inducible transgene expression specifically in the glomerular podocyte. We found that induction of claudin-1 gene expression in mature podocytes caused profound proteinuria, and with deep-etching freeze-fracture electron microscopy, we resolved the ultrastructural change in the claudin-1–induced SD-TJ transition. Notably, immunolabeling of kidney proteins revealed that claudin-1 induction destabilized the SD protein complex in podocytes, with significantly reduced expression and altered localization of nephrin and podocin proteins. Mechanistically, claudin-1 interacted with both nephrin and podocin through cis- and trans-associations in cultured cells. Furthermore, the rat puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis model, previously suspected of undergoing SD-TJ transition, exhibited upregulated expression levels of claudin-1 mRNA and protein in podocytes. Together, our data attest to the novel concept that claudins and the TJ have essential roles in podocyte pathophysiology and that claudin interactions with SD components may facilitate SD-TJ transition that appears to be common to many nephrotic conditions.

Keywords: tight junction, slit diaphragm, claudin, proteinuria, protein interaction, podocyte

Cell-cell adhesion is maintained mainly through adherens junctions (AJs) and tight junctions (TJs), which are important for barrier function in epithelial and endothelial cells.1,2 Podocyte epithelial cells are unique cells in the Bowman's capsule of the kidneys that wrap around capillaries of the glomeruli.3 In immature glomeruli, the presumptive podocytes are connected by apical TJs, which form between podocytes near their apical surfaces during the comma and S-shape stages of glomerular formation.4,5 Mature podocytes are totally devoid of TJs and form the specialized cell-cell junction called slit diaphragm (SD), which is one of the major impediments to protein permeability across the glomerular filtration barrier.6 Podocytes contain the important transmembrane protein, nephrin, which is considered to make the SD,7,8 together with other transmembrane proteins, such as podocin,9 Neph1,10,11 and Fat1.12 Using several techniques including fractionation, immunofluorescence, and immunoelectron microscopy, TJ proteins such as junction adhesion molecule A (JAM-A), occludin, coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR), and zona occluden-1 (ZO-1), have also been found in the SD of the mature podocyte.13–15 The functional roles of TJ components in mature SD under physiologic and pathologic conditions are still an unresolved question.

Nephrin plays a central role in the establishing of adhesive properties of the SD.8,16 Nephrin is a 130 kDa transmembrane protein of the Ig superfamily, with a short cytoplasmic C-terminus, a transmembrane domain, a fibronectin type 3 domain, and eight Ig-like domains.7,17 Nephrin, through cis-interaction with other proteins such as podocin, CD2-associated protein (CD2AP), and Neph1, forms the key intracellular SD protein complex.9,11 Nephrin trans-interactions between adjacent podocyte foot processes have been proposed to generate the SD architecture with the characteristic zipper-like appearance.8,18 Under certain nephrotic conditions, the membrane of the podocyte foot processes comes into close apposition, generating a TJ-like structure between neighboring foot processes.19 The SD-TJ transition has also been observed in nephrin knockout animals16 and in podocin knockout animals.20 Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying the SD-TJ transition and how such structural transition may lead to glomerular permeability defects for macromolecules continues to be a major mystery.

Claudins are the major structural and functional component of the TJ. Claudins are tetraspan proteins consisting of a family of at least 28 members, which are expressed in various segments of the nephron, including the glomerulus.21 In renal tubular epithelia, claudins confer ion permselectivity to the paracellular transport pathway resulting in differences in transepithelial permeabilities.21 Some claudins have been detected in the glomeruli of adult mice kidneys22,23; however, their roles in the glomerulus remain mostly elusive. Deregulation or mislocalization of claudin has been found in several nephrotic disorders. For example, the nephrin knockout mice showed compensated and increased expression of claudin-3 in podocyte foot processes, which was normally absent in glomeruli but presumably replaced the SD with TJ.24 Claudin-1, which is primarily expressed at TJs of the glomerular parietal epithelium in healthy mice kidneys, is profoundly upregulated in podocytes from animals with diabetic nephropathy.25 However, the precise role of claudin-1 in podocyte pathophysiology has not been definitively elucidated. Here, we have generated a novel animal model expressing claudin-1 in podocytes, controlled by doxycycline. We speculate that gain of claudin function in the podocyte may disrupt normal SD architecture, leading to glomerular filtration defects. Such structural and functional changes may be because claudin directly interacts with the SD components, such as nephrin and podocin, through cis- or trans-association. These interaction events may represent a novel mechanism underlying SD-TJ transition that is common to many nephrotic diseases.

Results

Generation of Transgenic Mice That Express Claudin-1 in Podocytes in Doxycycline-Controllable Manner

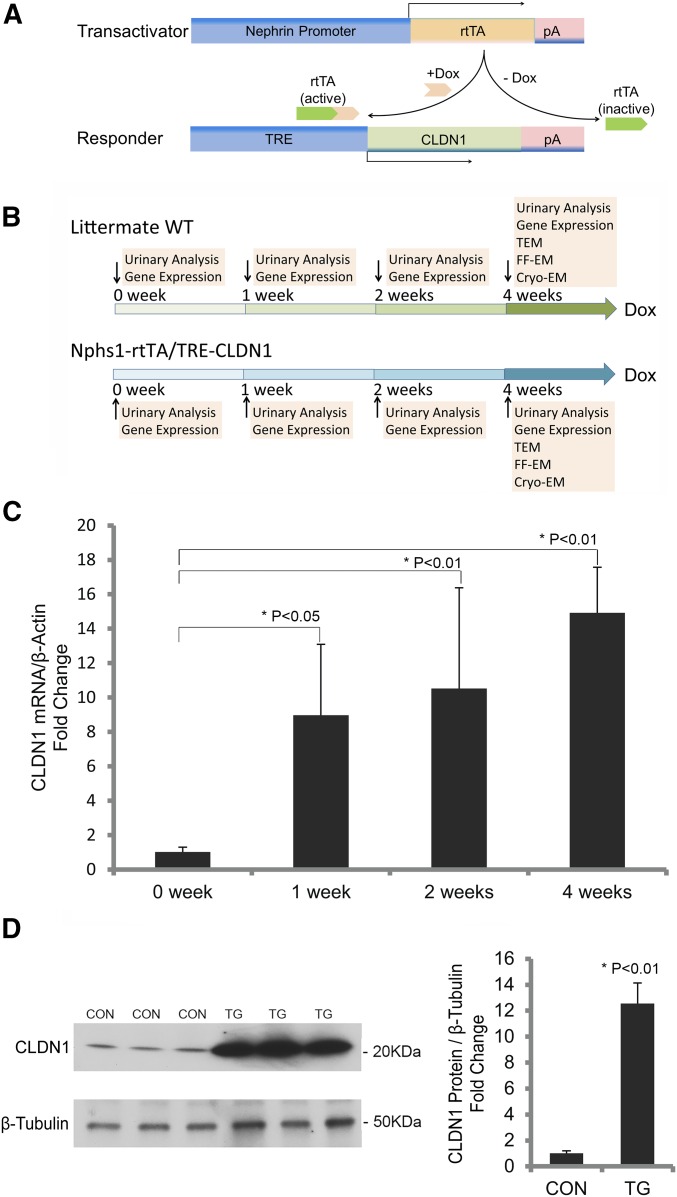

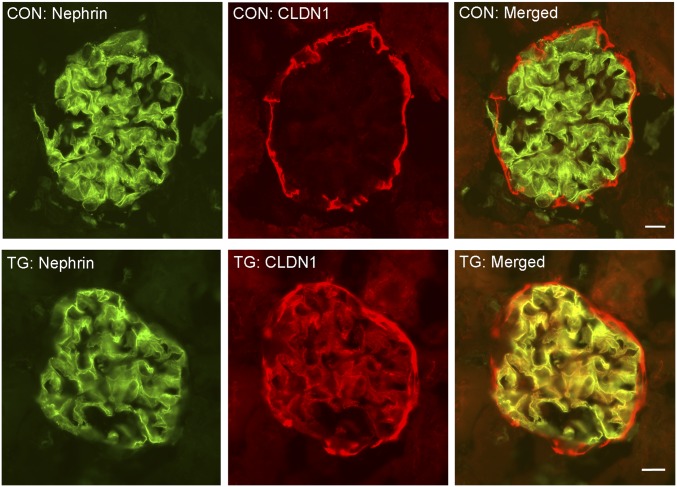

To study the role of claudin in podocyte pathophysiology, we have generated an animal model with inducible expression of claudin-1 in the podocyte, under the control of doxycycline. In this model, one transgenic mouse line, Nphs1-rtTA, utilized the 4.1 kb Nphs1 (nephrin) promoter to drive the production of the reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (rtTA) in the podocyte.26 The other transgenic mouse line, TRE-CLDN1, encoded the full-length mouse claudin-1 cDNA under the control of the (TetO)7/CMV responsive element (TRE) promoter.27 Cohorts of double transgenic Nphs1-rtTA/TRE-CLDN1 mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates lacking both loci as controls were generated by intercrossing the single transgenic animals (see Concise Methods). In the presence of doxycycline, the doxycycline-rtTA complex binds to the TRE promoter in the TRE-CLDN1 responder mice to induce transcription of the claudin-1 gene (Figure 1A). The podocyte specificity of the rtTA gene expression in the Nphs1-rtTA mouse has previously been well established.26 The doxycycline controllability of the claudin-1 gene expression in the TRE-CLDN1 mouse has been examined before in the brain vasculature by crossing to an endothelium-specific, Tie2-tTA transgenic mouse.27 The age-matched (8–10 weeks old) Nphs1-rtTA/TRE-CLDN1 transgenic (TG) and control (CON) animals of mixed sex were treated with a doxycycline-supplemented diet (0.15% w/w) continuously for up to 4 weeks. At the beginning of the treatment (0 weeks), 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks after the treatment, urinary analyses and gene expression were carried out for both groups of animals (vide infra) (Figure 1B). To accurately quantify the gene expression changes in the glomerulus, we have utilized a published protocol to mechanically isolate the glomerular tufts from the mouse kidney by perfusing spherical superparamagnetic beads, termed Dynabeads (4.5 μm in diameter), through the heart (see Concise Methods, adapted from Takemoto et al.28). Notably, the glomeruli isolated with this approach lack the Bowman’s capsule, i.e., the parietal epithelial cell (PEC) layer (Supplemental Figure 1),28 which is known to express a high level of claudin-1.29,30 There was no difference in the claudin-1 mRNA level from the isolated glomerular tufts between TG and CON animals at the 0-week time point. Doxycycline had no effect on claudin-1 expression in CON animals. The doxycycline treatments, in contrast, significantly increased the transcript level of claudin-1 in the TG animals starting from week 1 (by 8.79-fold, P<0.05, n=3; versus week 0) and through week 2 (by 10.31-fold, P<0.01, n=3; versus week 0) to week 4 (by 14.62-fold, P<0.01, n=3; versus week 0) time points, when quantified with real-time PCR and normalized to the β-actin mRNA level (Figure 1C). The claudin-1 protein levels from isolated glomerular tufts were measured in CON and TG animals at the week 4 time point with Western blotting. Densitometric analyses revealed a 12.56-fold increase in claudin-1 protein levels of TG compared with CON animals (P<0.01, n=3; normalized to β-tubulin protein) (Figure 1D). In TG animals receiving doxycycline treatment for 4 weeks, pronounced claudin-1 protein labeling could be found within the glomerular tuft, while the PEC expression of claudin-1 remained similar when compared with CON animals (Figure 2). Counterstaining for nephrin revealed significant cellular colocalization with claudin-1 in the podocytes of TG animals (Figure 2). Notably, two independent TRE-CLDN1 mouse lines, #23949 and #23974, were crossed to Nphs1-rtTA and analyzed in this study (see Concise Methods). The data shown in Figures 1 and 2 were from the line #23949. The line #23974 showed similar levels of doxycycline-dependent regulation of claudin-1. Together, these results establish a claudin-1–inducible expression animal model with cellular specificity in the glomerular podocyte.

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of claudin-1–inducible animal model. (A) Diagram showing the genetic loci of transactivator and responder genes. (B) Diagram showing the experimental strategy to induce claudin-1 gene expression with doxycycline at different time points. (C) Statistic graph showing the transcript levels of claudin-1 in isolated mouse glomeruli from TG animals receiving doxycycline treatment for different durations. n=3 in all groups and all data points are relative to β-actin transcript levels. (D) Western blots and statistic graph showing the protein levels of claudin-1 in isolated mouse glomeruli from TG versus CON animals after 4 weeks of doxycycline treatment. n=3 in both groups and quantitation of claudin-1 is relative to β-tubulin protein levels. Cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; Dox, doxycycline; FF-EM, freeze-fracture electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 2.

Cellular localization of claudin-1 protein in mouse glomeruli. Immunofluorescent micrographs showing the cellular localization of claudin-1 and nephrin in CON and TG animals. Scale bar, 10 μm.

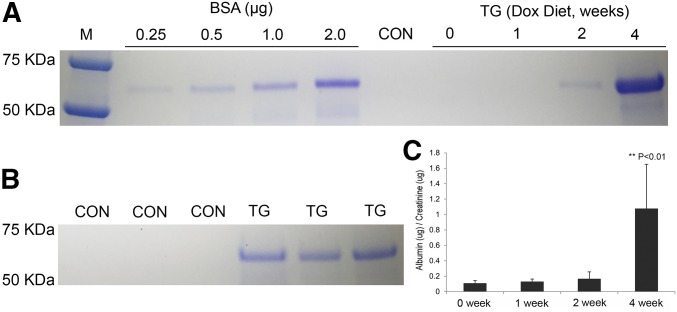

Overexpression of Claudin-1 in Podocytes Leads to Proteinuria

The age-matched CON and TG (line #23949) mice were first analyzed for the albumin protein abundance levels in spot urine samples at different time points described previously in this study (Figure 1B). There was no detectable albumin in the CON mouse urine throughout the doxycycline treatment period (Figure 3, A and B). In the TG group, mild albuminuria started to appear in some animals after 2 weeks of doxycycline treatment (Figure 3A); by 4 weeks, all animals developed pronounced albuminuria (n=3) (Figure 3, A and B). We then monitored the renal function of a large cohort of TG animals at different treatment time points (0–4 weeks; n=14 for each time point) with 24-hour metabolic cage analyses. There was no significant difference in body weight throughout the treatment period from 0 to 4 weeks (Table 1). The urinary volumes and the creatinine clearance rates remained unchanged by doxycycline treatment (Table 1). The urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio was significantly increased by 9.89-fold (P<0.01, n=14) in TG mice at week 4 compared with week 0 (Figure 3C, Table 1), despite well defended urinary osmolality (Table 1). The second TG line, #23974, also showed pronounced proteinuria after 4 weeks of doxycycline treatment. These data establish a strong causal relationship of claudin-1 gene induction with glomerular filtration defects.

Figure 3.

Urinary albumin levels in claudin-1–induced animals. (A) Coomassie blue-stained gel showing the albumin levels in spot urine samples from the time chasing experiments carried out in TG animals receiving doxycycline treatment for indicated durations. (B) Coomassie blue-stained gel showing the albumin levels in 24-hour urine samples from TG versus CON animals after 4 weeks of doxycycline treatment. n=3 in both groups. (C) ELISA quantitation showing the albumin levels in 24-hour urine samples from TG animals receiving doxycycline treatment for indicated durations. n=14 in all groups and quantitation of urinary albumin is relative to urinary creatinine levels (μg/μg). Dox, doxycycline.

Table 1.

The 24-hour renal metabolism in TG animals receiving doxycycline for indicated durations

| Group | Week 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, g | 18.34±0.96 | 20.28±0.95 | 19.13±0.75 | 19.87±0.49 |

| UV, µl/24 h per g | 68.66±8.11 | 52.80±4.98 | 65.57±8.12 | 59.44±6.50 |

| CCr, ml/24 h per g | 2.60±0.47 | 2.11±0.23 | 2.59±0.17 | 2.44±0.37 |

| UOsm, Osm/kg water | 1.544±0.128 | 1.663±0.092 | 1.755±0.117 | 1.576±0.077 |

| UAl/UCr, µg/µg | 0.109±0.035 | 0.131±0.034 | 0.167±0.089 | 1.078±0.574a |

Values are expressed as mean ±SEM.

UV, urinary volume; CCr, creatinine clearance rate; UOsm, urinary osmolality; UAl/UCr, the ratio of urinary albumin to urinary creatinine.

P<0.01 versus week 0; n=14 mice for each time point.

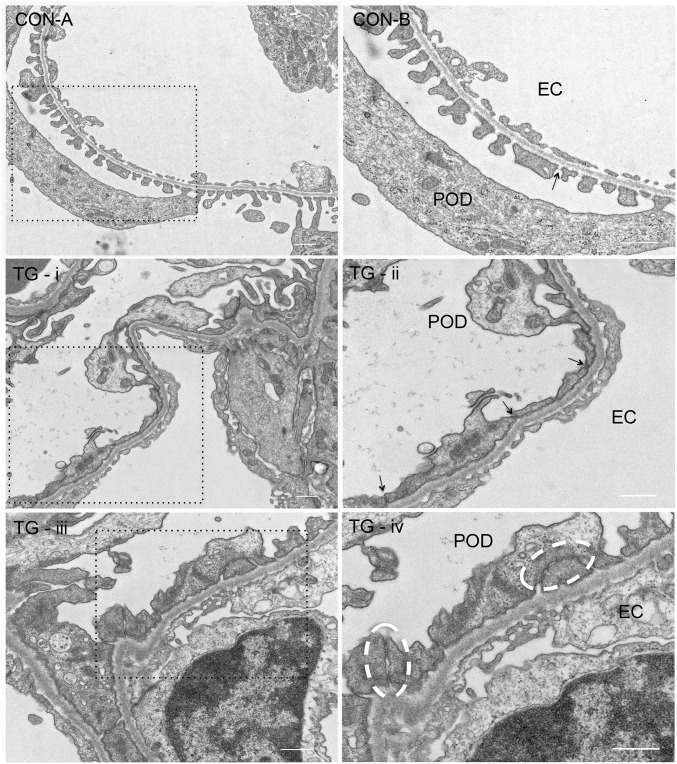

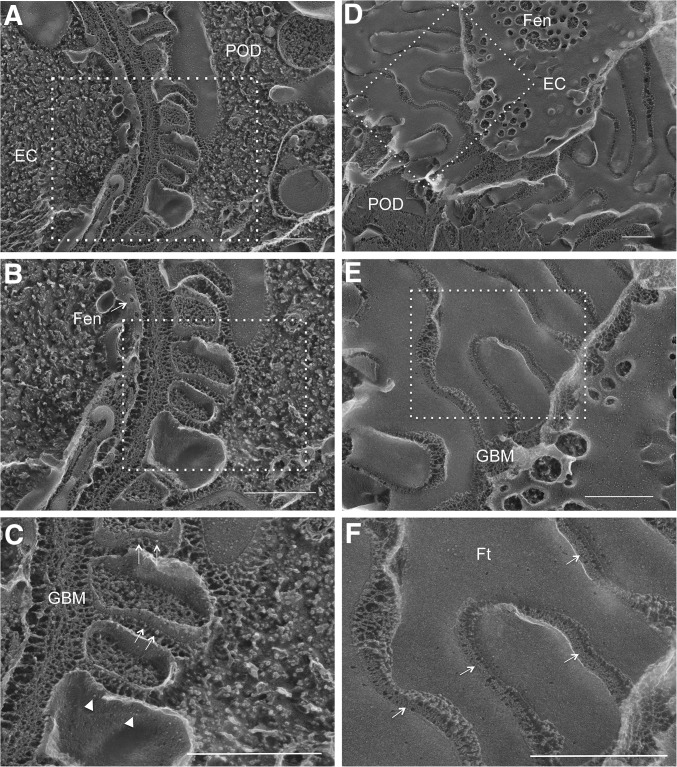

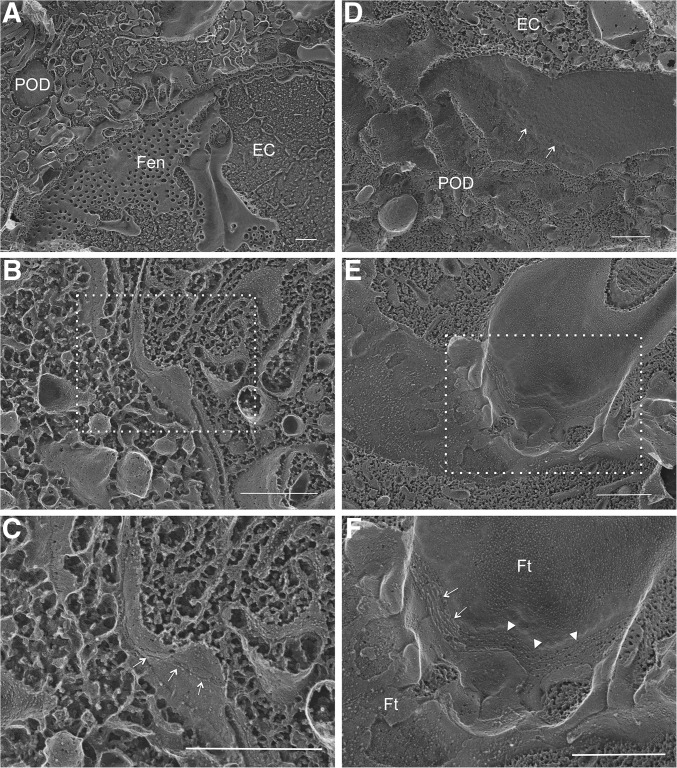

Podocyte Cell-Cell Junction Ultrastructural Changes in Claudin-1 Overexpression Mice

In thin-section electron microscopy (EM) of normal kidney glomeruli, podocyte foot processes were separated by the filtration slit (Figure 4, CON-A). In cross-sectional view, the SD spanned the filtration slit above the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and appeared to be single cross-strands (Figure 4, CON-B), which were first described by Farquhar et al.31 In kidney glomeruli of TG animals stimulated with doxycycline for 4 weeks, mild foot process effacement can been seen (Figure 4, TG-i). A more striking anatomic change was the disappearance of the filtration slit between the foot processes (Figure 4, TG-ii, arrow). The neighboring foot process membrane was closely anastomosed (Figure 4, TG-iii), reminiscent of the TJ found in the epithelium or the endothelium. At higher magnification, multiple membrane “fusion” or “kissing” points can be seen between these foot processes (Figure 4, TG-iv, circle), which are characteristic of the TJ structure.32 The best way to reveal the TJ architecture is with freeze-fracture EM, first described by Goodenough et al.1,33 Freeze fracture is a technique of breaking frozen cell membranes into half-membrane leaflets and presenting en face views of the subcellular organization of membrane structures at macromolecular resolution.34 While the regular freeze-fracture technique works well for structures buried inside of the membrane, such as the TJ, structures exposed outside of the membrane, such as the intracellular cytoskeleton or the extracellular SD, turn out to be difficult to reveal with this technique because the fractured surface is covered by a layer of ice that has hidden the fine details of the structures beneath or above the cleaved membrane leaflet. Heuser et al. have made an important modification to the freeze-fracture technique by introducing a deep-etching step (i.e., shallow freeze-drying to allow the sublimation of surface ice under vacuum) and were able to reveal the fine details of caveolea and clathrin-coated pits.35–37 Notably, Karnovsky and Ryan first used the freeze-fracture deep-etching technique to show that the SD can be seen as a highly ordered, zipper-like substructure.38 Here, we used a freeze-fracture deep-etching protocol modified from that of Heuser et al. (see Concise Methods37) to study the architectural changes of SD to TJ transition when comparing CON and TG animals described elsewhere of this study. In CON glomeruli, when the plane of fractured membrane is perpendicular to the GBM (Figure 5, A–C), the SD can be seen as protein particles anchored on the E-face (Figure 5C, arrow) or the P-face (Figure 5C, arrowhead) of the cleaved membrane of the podocyte foot processes, as described by Karnovsky and Ryan.38 When the fractured membrane is coplanar to the GBM (Figure 5, D–F), fine SD architecture can be seen with the characteristic zipper-like pattern (Figure 5F, arrow). In TG glomeruli, such SD structure clearly gives way to TJ structure (Figure 6). From a perpendicular view, the slit space disappears between the neighboring foot process membranes (Figure 6, A–C). The two neighboring membranes are joined by a strand of TJ particles (Figure 6C, arrow). From a parallel view, the loss of slit space is more convincing (Figure 6, D–F) and well elaborated TJ strands can now be found between two conjoining foot processes, showing clear P-face (Figure 6F, arrow) to E-face (Figure 6F, arrowhead) transition. Together, these results reveal the ultrastructural role of claudin-1 in reshaping the podocyte cell-cell junction.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron microscopy imaging of mouse podocytes. EM micrographs showing ultrathin podocyte sections from CON and TG animals. CON-B is the magnified view of the boxed region in CON-A. CON-B: arrow indicates SD. TG-ii is the magnified view of the boxed region in TG-i. TG-ii: arrow indicates TJ. TG-iv is the magnified view of the boxed region in TG-iii. TG-iv: white circle indicates multiple membrane fusions characteristic of the TJ structure. The fields TG-i and -ii and TG-iii and -iv are from two separate animals. We have examined four TG animals at the 4-week time point and all showed SD-TJ transition. EC, endothelial cell; POD, podocyte. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Figure 5.

Freeze-fracture deep-etching electron microscopy imaging of CON mouse glomeruli. EM micrographs showing the replica of fractured glomeruli from both the perpendicular view (A–C) and the parallel view (D–F) relative to the GBM. Panels of (B) and (C) are serial magnification of the boxed region in (A) and (B), respectively. Panels of (E) and (F) are serial magnification of the boxed region in (D) and (E), respectively. (C) Arrow indicates the SD as protein particles anchored on the E-face of the fractured membrane and arrowhead indicates the SD protein particles on the P-face of the fractured membrane. (F) Arrow indicates the SD as zipper-like structure. EC, endothelial cell; Fen, fenestration; Ft, podocyte foot process; POD, podocyte. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Figure 6.

Freeze-fracture deep-etching electron microscopy imaging of TG mouse glomeruli. EM micrographs showing the replica of fractured glomeruli from both the perpendicular view (A–C) and the parallel view (D–F) relative to the GBM. (C) is the magnified view of the boxed region in (B). (F) is the magnified view of the boxed region in (E). (C) Arrow indicates TJ as a linear protein particle strand. (D) Arrow indicates a TJ strand connecting the P-E face transition of fractured membranes. (F) Arrow indicates TJ strands on the P-face of the fractured membrane and arrowhead indicates TJ strands on the E-face of the fractured membrane. EC: endothelial cell; Fen: fenestration; Ft: podocyte foot process; POD: podocyte. Scale bar, 500 nm.

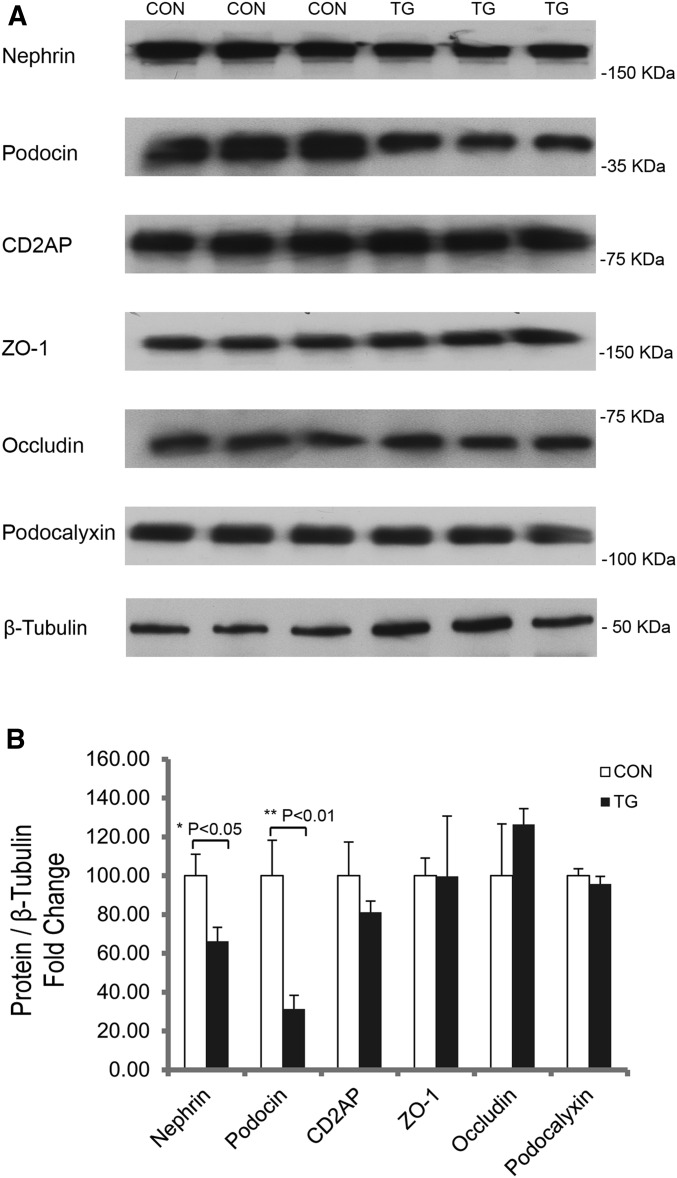

The SD Components Are Destabilized by Podocyte Claudin-1

Knowing that claudin-1 promotes SD to TJ transition in the podocyte, we then addressed the underlying molecular mechanism. In normal podocytes, there are two important biologic processes: the interdigitation of foot processes and the formation of SD. For proper foot process to develop, the function of podocalyxin is essential and believed to give the podocyte membrane surface anion charge through its sialic acids.39 Accordingly, no foot process has been found in the podocalyxin knockout mouse podocytes, and TJ replaces SD in adjoining podocyte cell bodies.40 We therefore measured the mRNA and protein levels of podocalyxin in isolated glomeruli from CON and TG animals described elsewhere of this study. As shown in Figure 7 and Supplemental Figure 2, there was no difference in podocalyxin transcription or protein abundance between CON and TG groups. The functional SD is believed to comprise three most important podocyte proteins, nephrin, podocin, and CD2AP, which interact with each other to form a high-order oligomer.9 The SD to TJ transition is evident in nephrin knockout animals16 and in podocin knockout animals.20 Here, we found that in TG animals stimulated with doxycycline for 4 weeks, nephrin and podocin protein abundances were clearly reduced compared with CON animals (Figure 7A), despite the fact that the transcripts of both genes remained unchanged (Supplemental Figure 2). Densitometric analyses revealed a 33.74% decrease in nephrin level (P<0.05, n=3; normalized to β-tubulin protein) and a 68.71% decrease in podocin level (P<0.01, n=3; normalized to β-tubulin protein) of TG compared with CON glomeruli (Figure 7B). Immunolabeling of kidney sections revealed a marked reduction of podocin signal in TG compared with CON glomeruli (Supplemental Figure 3). Notably, both nephrin and podocin localization patterns appeared more diffuse in TG than in CON glomeruli (Supplemental Figure 3). No change in CD2AP mRNA or protein abundance was found in TG glomeruli (Figure 7, Supplemental Figure 2). The SD has long been known to contain TJ molecules, such as ZO-1 and occludin, while their roles in normal slit filtration function remain controversial.13,14 Invariably, both genes were upregulated in nephrotic animals treated with puromycin aminonucleoside or protamine sulfate.14,19 Here, we asked whether the claudin-1 effect in podocytes might be caused partially by changes in other TJ proteins, such as ZO-1 and occludin. To our surprise, none of these TJ molecules’ levels were affected in TG glomeruli (Figure 7, Supplemental Figure 2), supporting the concept that claudin-1 is the key molecule underlying SD to TJ transition. Together, these results have revealed a competing role of claudin-1 against the SD components nephrin and podocin.

Figure 7.

Protein abundance levels of the indicated genes from isolated mouse glomeruli. Western blots (A) and statistic graph (B) showing the protein levels of the indicated genes in isolated mouse glomeruli from TG versus CON animals after 4 weeks of doxycycline treatment. n=3 in all groups and quantitation is relative to β-tubulin protein levels.

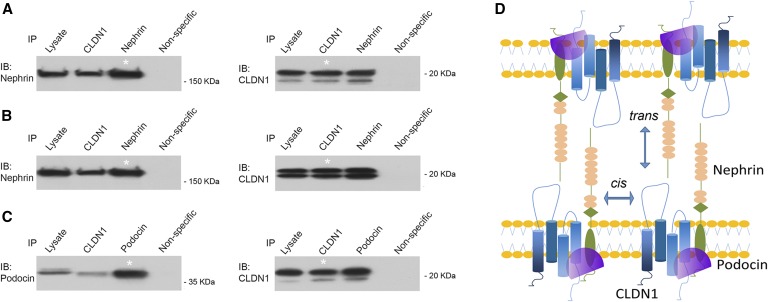

Claudin-1 Directly Interacts with Nephrin and Podocin

Claudin-1 demonstrates strong cis- and trans- self-interaction affinity,41 presumably through its extracellular loops,42 and when introduced to cells deficient of endogenous TJ components, is able to form recombinant TJ architecture by itself.41 Knowing that claudin-1 destabilized the SD components and promoted SD to TJ transition, we asked whether direct interaction of claudin-1 with nephrin or podocin might represent a plausible mechanism. Due to the remarkably complex biochemical structures of TJ and SD, claudin interactions and nephrin interactions (both cis and trans) in their native niche (epithelia or podocytes) may be difficult to delineate due to many other protein interactions already present within the macromolecular architecture. Simpler cell systems such as the human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells retained neither TJ nor SD, and have been widely used to study selective claudin interactions43 and nephrin interactions.8 To directly document the cis-interaction between claudin-1 and nephrin, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) in sparsely plated HEK293 cells transfected with two genes simultaneously, as previously described.43 At low cell density, which minimized the trans-interaction, anti–claudin-1 antibody was able to precipitate nephrin and anti-nephrin antibody reciprocally precipitated claudin-1 (Figure 8A). The CoIP approach for probing claudin trans-interaction was first used by Daugherty et al. in the study of claudin-5.44 We later adapted it to study how proteases regulated claudin-4 trans-interaction.45 Here, claudin-1 and nephrin were transfected into HEK293 cells independently, and the transfected cells were cocultured to form cell-cell junctions. Immunoblots showed that claudin-1 and nephrin coprecipitated with each other (Figure 8B). Notably, the trans-interaction affinity appeared similar to that of the cis-mode, suggesting that claudin-1 was capable of integrating into the nephrin-based SD structure (Figure 8D). Podocin has been found to interact with nephrin directly.9 Because the podocin protein is anchored into the intracellular leaflet of the membrane by only its short hydrophobic domain,46 it is regarded as an SD peripheral protein, unable to mediate trans-membrane interactions. Therefore, we probed its interaction with claudin-1 by the cis-mode. In HEK293 cells doubly transfected with claudin-1 and podocin, anti–claudin-1 antibody precipitated podocin, and vice versa (Figure 8C). Based on these results, we have come to the conclusion that claudin-1 directly interacts with both nephrin and podocin, which may disrupt the endogenous nephrin and podocin interactions that hold the SD in place (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Claudin-1 interacts with nephrin and podocin. (A) CoIP of claudin-1 and nephrin in doubly transfected HEK293 cells to determine the cis-interaction of claudin-1 with nephrin. (B) CoIP of claudin-1 and nephrin in singly transfected, cocultured HEK293 cells to determine the trans-interaction of claudin-1 with nephrin. (C) CoIP of claudin-1 and podocin in doubly transfected HEK293 cells to determine the cis-interaction of claudin-1 with podocin. *Lane shows 10% of the input amount of other lanes. (D) Diagram showing an integrated model of cis- and trans-interaction of claudin-1 with nephrin and podocin. IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Claudin-1 Gene Expression Levels Are Upregulated in Puromycin Aminonucleoside Nephrosis

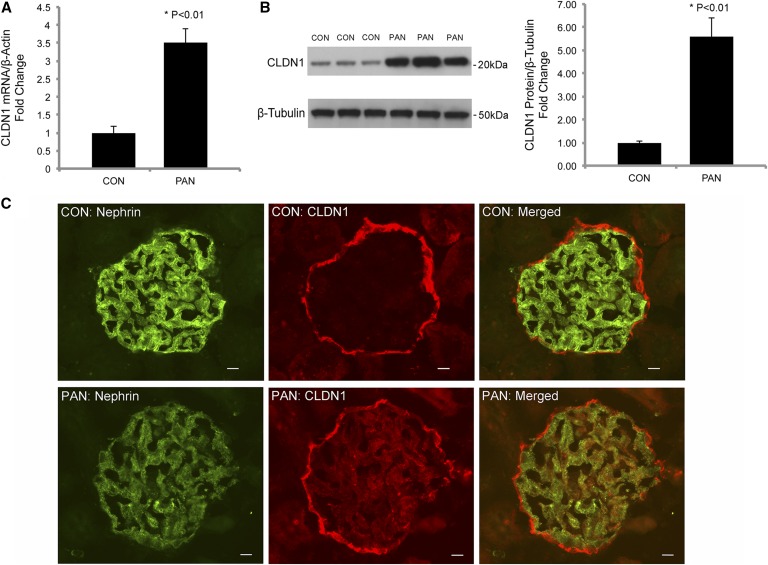

The puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis (PAN) rat model is a well established, experimental, nephrotic disease model. The filtration slits in PAN podocytes are greatly narrowed and the SDs are displaced by TJ-like structures.19,47 While the TJ proteins ZO-1 and occludin were previously found upregulated in PAN,14,19 it is important to note that neither protein is able to reconstitute the TJ architecture on its own.32 Claudins, by cis- and trans-interactions, are the only molecules capable of polymerizing into functional TJ strands.41 Knowing that claudin-1 overexpression in podocytes induced SD-TJ transition, we asked whether claudin-1 gene expression may be upregulated in PAN as a mechanism to explain the TJs observed by Farquhar et al.47 The age- (5–6 week old) and sex- (male) matched rats were induced with PAN by nine daily injections of puromycin aminonucleoside (see Concise Methods) according to a published protocol.48 At the end of treatment, we performed mechanical isolation of the glomerular tufts from the rat kidney by perfusing spherical Dynabeads and passing through a series of sieves (see Concise Methods).49 The isolated glomeruli from PAN and CON rats were analyzed for difference in claudin-1 gene expression levels. The claudin-1 mRNA levels, quantified with real-time PCR, showed a 3.52-fold increase in PAN compared with CON animals (P<0.01, n=3; normalized to the β-actin mRNA) (Figure 9A). The claudin-1 protein levels in PAN animals were 5.57-fold higher than those in CON animals (P<0.01, n=3; normalized to the β-tubulin protein) (Figure 9B), as revealed by Western blotting and densitometric analyses. In the CON glomerulus, claudin-1 protein labeling was concentrated on the PEC layer (Figure 9C). The PAN glomerulus showed pronounced claudin-1 protein labeling not only on the PEC layer, but also in the glomerular tuft (Figure 9C). Dual staining revealed cellular colocalization of claudin-1 with nephrin in the PAN glomerulus, indicating the podocyte origin of claudin-1 expression (Figure 9C). Notably, the nephrin protein labeling was markedly lower in PAN than in CON glomerulus, consistent with previous reports that PAN repressed nephrin gene expression in the podocytes.50,51 Together, these results suggest that claudin-1 upregulation may be a common mechanism for many nephrotic conditions, including PAN.

Figure 9.

Claudin-1 gene expression in PAN. (A) Statistic graph showing the transcript levels of claudin-1 in isolated rat glomeruli from PAN versus CON animals. n=3 in both groups and all data points are relative to β-actin transcript levels. (B) Western blots and statistic graph showing the protein levels of claudin-1 in isolated rat glomeruli from PAN versus CON animals. n=3 in both groups and quantitation of claudin-1 is relative to β-tubulin protein levels. (C) Immunofluorescent micrographs showing the claudin-1 and nephrin protein localization patterns in PAN versus CON animals. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

The association of anatomic changes in the SD with nephrotic diseases has been described before in human patients52,53 and experimental animals.48,54 Farquhar et al. first recognized the presence of TJ in the residual slits with both thin-section EM and freeze-fracture EM.47,48 Using molecular tools, Farquhar et al. have demonstrated that normal SD contains TJ proteins such as ZO-1, JAM-A, occludin, and CAR.13,14,55 More importantly, these TJ molecules are invariably upregulated under nephrotic conditions, implicating their compensating roles in the face of SD dissolution.14 However, from the works of Tsukita and colleagues, it becomes clear that the above-mentioned TJ molecules are dispensable for TJ formation, and that it is the claudins that establish the fundamental architecture for TJ.41,56 The normal podocyte expression of claudin is generally low, and here we have found that claudin-1 is markedly upregulated in nephrotic animals treated with puromycin aminonucleoside. The hypothesis that claudin mediates SD-TJ transition has become even more tangible based upon a genomic analysis of genes showing compensated regulation in podocytes depleted with nephrin.24 With transcriptional profiling, Doné et al. have found that claudin-3 was the only gene significantly upregulated in nephrin knockout mouse podocytes.24 We now provide compelling evidence that introducing a claudin molecule, claudin-1, normally absent from the podocyte is sufficient to induce SD-TJ transition in vivo in mouse podocytes. Mechanistically, the claudin-1 effect may act through direct interaction with nephrin and podocin, in both cis- and trans-mode, and destabilization of the SD protein complex. The nephrin trans-interaction is important not only for podocyte cell adhesion,8 but also for intracellular signaling activation involving the Fyn-Nck pathway.57 It is conceivable that claudin-1 trans-interaction with nephrin may interrupt normal podocyte cell adhesion or its intracellular signaling cascades. Intriguingly, TM4SF10, as a member of the expanded claudin family, has been found to suppress Fyn activity and loosen the nephrin anchorage to cytoskeleton upon puromycin aminonucleoside treatment.58 It is also possible that claudin-1 may form a “hybrid” junction with nephrin. In a series of pioneering studies using electron tomography, Tryggvason and colleagues have revealed that normal SD exhibits a zipper-like structure with alternating periodic cross strands of fixed length (approximately 35 nm) purported to derive from nephrin trans-interactions.59 Other types of structures, half the length of the 35-nm cross-strands, were found on the cell membrane close to the SD or in narrow slits occasionally found between normal foot processes.59 According to the claudin crystal structure, its extracellular domain is globular and <2 nm in length.42 The vitrified solution structure of nephrin ectodomain revealed twisted strands made of nephrin dimers. The length of a nephrin monomer is no more than half of 35 nm.59 Although the amino acid loci important for claudin-nephrin trans-interaction remain undefined, a structure made of one claudin molecule and one nephrin molecule (Figure 8D) would fit well with the spatial dimension of the shorter cross-strands observed by Tryggvason and colleagues. Additional claudin cis-interaction with nephrin and podocin would further support the theory that claudin is making a stable hybrid junction spanning the filtration slit. Claudin overexpression in the podocyte may alter the molecular ratio between the short hybrid strand and the long SD strand, and trigger a chain reaction leading to the destabilization of SD and the appearance of TJ.

The clinic significance of podocyte claudin-1 in causing diabetic proteinuria has recently been described by Hasegawa et al.25 There seems to be an epigenetic program in the podocyte suppressing claudin-1 gene expression in normal physiology, and such a program is often compromised in diabetic kidneys, leading to uncontrolled overexpression of claudin-1.25 Our results have provided strong proof that upregulation of claudin-1 per se in the podocyte is able to induce proteinuria. However, it needs to be recognized that diabetic nephropathy is a multifaceted disease affecting the expression and function of many more SD and TJ genes in the podocyte. For example, the nephrin and podocin gene expression levels were significantly reduced in diabetic podocytes, accompanied by a marked decrease in the mean slit width (i.e., a tighter slit).60,61 ZO-1 expression and localization were also altered in diabetic podocytes and podocytes treated with high glucose concentration.62 Intriguing, there exists a counterintuitive relationship of tighter slits to higher albumin permeability, not only in diabetic nephropathy but also in many other forms of nephrotic diseases. Smithies offered a hypothetical model to explain this relationship, referred to as the gel diffusion model.63 In the model, the GBM acts as a gel to restrict the diffusion of macromolecules such as albumin, which is independent of the GFR. The SD allows the free flow of water and small solutes that is directly correlated to the GFR. Tighter filtration slits would lead to greatly reduced fluid flow rates through the SD, but would have little effect on the amount of albumin that crosses the GBM by diffusion. As a consequence, the relative albumin concentration in the filtrate would be higher. Our results are in direct favor of this model. We have demonstrated that overexpression of claudin-1 in the podocyte can replace the SD with the TJ. The TJ is a natural barrier to water and small solutes.32 Nevertheless, it is important to note that neither the urinary flow rate nor the creatinine filtration rate (an estimate of GFR) was significantly altered in the TG animals with inducible expression of claudin-1 (Table 1). These data may suggest more complex secondary compensation in the face of reduced fluid permeability in the podocyte, as described in tubuloglomerular feedback mechanisms.

Concise Methods

Reagents, Antibodies, and Cell Lines

The primers, chemicals, and antibodies used in this study are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. The full-length cDNAs of the following genes were cloned in this study: mouse claudin-1 (NM_016674), human nephrin (NM_004646), and human podocin (NM_014625). The mouse claudin-1 and human podocin genes were purchased from Origene Technologies (Rockville, MD); the human nephrin gene was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Vernon Hills, IL). Human HEK293 cells (a kind gift from Joan Brugge, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate.

Animals

All animal experiments conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee. The TRE-Claudin-1 transgenic mice (provided by Dr. Britta Engelhardt, University of Bern, Switzerland) contained the tet-response element upstream of the mouse claudin-1 cDNA. Genotyping PCR using the primers CMV-IE FW and IRES REV2, amplified a product of 700 bp in size from the tail DNA of TRE-Claudin-1 transgenic mice. Two independent TRE-Claudin-1 mouse lines, #23949 and #23974, were studied here. Both lines had been backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for over seven generations.27 The Nphs1-rtTA transgene mice (line #8; provided by Dr. Jeffery Miner, Washington University) contained the 4.1-kb mouse nephrin promoter driving rtTA-3G cDNA (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA), followed by an SV40 polyadenylation signal.26 The Nphs1-rtTA mice were identified by PCR using a forward primer (Nphs1) and a reverse primer (rtTA) to generate an approximately 400-bp amplicon. The Nphs1-rtTA mouse was originally generated on a mixed background of B6CBAF1 but was backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background in our lab. Double transgenic (Nphs1-rtTA/TRE–claudin-1) mice were obtained by breeding the Nphs1-rtTA activator mice with the TRE-claudin-1 responder mice. To induce transgene expression, mice were fed with the TestDiet Modified Rodent Diet 5755 containing 0.15% doxycycline (purchased from El-Mel, Inc., Florissant, MO) at indicated time points. Double transgenic experimental mice remained on doxycycline-supplemented diet continuously, as did their age-matched littermate controls, allowing them to be analyzed in paired groups. All animals had free access to water and were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture rapidly after initiation of terminal anesthesia, and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes. Kidneys were dissected out and immediately frozen at –80°C.

Animal Metabolic Studies

Mice were housed individually in metabolic cages (Harvard Apparatus) with free access to water and food for 24 hours. Urine was collected under mineral oil. The plasma and urine electrolyte levels were determined with the Roche Cobas clinical analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The creatinine levels were measured with an enzymatic method that was independent of plasma chromogens. The fractional excretion of electrolytes was calculated using the following equation: FEion=V×Uion/(GFR×Pion), where GFR was calculated according to the clearance rate of creatinine (GFR=V×Ucreatinine/Pcreatinine). Spot urine samples from TG or CON animals were collected according to genotype for analysis by SDS-PAGE. The urinary albumin levels were measured using the ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratory).

Isolation of Glomeruli from the Mouse Kidneys

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and perfused with 8×107 Dynabeads (4.5 μm in diameter) diluted in 40 ml of 0.9% saline, through the heart. The kidneys were removed, minced into 1 mm3 pieces, and triturated with 13G, 15G, and 17G cannulas, sequentially. In contrast to the published protocol,28 we did not use any collagenase but were still able to isolate clean and intact glomeruli. The triturated cells were passed through a 70 μm strainer using a flattened pestle. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 250×g for 5 minutes, resuspended with fresh 0.9% saline, and placed on top of a magnetic particle concentrator, allowing the collection of Dynabead-containing glomeruli. The isolated glomeruli were washed for at least three times with 0.9% saline to remove any tubule contamination. The entire procedure was carried out on ice to minimize the changes in gene expression profile.

PAN Rat Model

The Sprague–Dawley male rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), with 100–150 g initial body wt and weighing 150–200 g when euthanized, were given nine daily subcutaneous injections of puromycin aminonucleoside dissolved in 0.9% saline at the dose of 1.67 mg/100 g body wt. CON animals received 0.9% saline injections. The nine daily injection protocol was selected because previous experiments had established that at this time point proteinuria was nearly maximal, while glomerular changes were primarily in the podocytes.54,64 On the 10th day, the rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and perfused with 4×108 Dynabeads (4.5 μm in diameter) diluted in 200 ml of 0.9% saline, through the heart. The kidneys were removed, minced into 1 mm3 pieces, and triturated with 13G, 15G, and 17G cannulas, sequentially. The triturated cells were passed sequentially through three sieves of 250 μm, 150 μm, and 75 μm, respectively. The cell suspension collected on the 75 μm sieve was centrifuged at 250×g for 5 minutes, resuspended with fresh 0.9% saline, and placed on top of a magnetic particle concentrator, allowing the collection of Dynabead-containing glomeruli. The isolated glomeruli were washed for at least three times with 0.9% saline to remove any tubule contamination. The entire procedure was carried out on ice to minimize the changes in gene expression profile.

Real-Time PCR Quantification

Total RNA was extracted from isolated glomeruli by using TriZol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cellular mRNA was reverse-transcribed using the Superscript-III Kit (Invitrogen) followed by real-time PCR amplification using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the Eppendorf Realplex2S system. The primers used for real-time PCR analyses are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Results were expressed as 2−∆Ct values with ∆CT = Ctgene– Ctβ-actin.

CoIP

The HEK293 cells coexpressing CLDN1 with podocin or nephrin (for studying cis-interaction) or the cocultured HEK293 cells expressing CLDN1 or nephrin individually (for studying trans-interaction) were lysed in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) by 25–30 repeat passages through a 25-gauge needle, followed by centrifugation at 5000×g. The membranes of lysed cells were extracted using the CSK buffer (150 mM sodium chloride; 1% Triton X-100; 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0; and protease inhibitors). The membrane extract was precleared by incubation with protein A/G-sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) prior to CoIP. The precleared membrane extract was incubated for 16 hours at 4°C with anti-CLDN1, anti-podocin, anti-nephrin, or anti-mouse IgG (as negative CON) antibodies. Antibody-bound material was pelleted with protein A/G-sepharose, washed three times with CSK buffer, and detected by immunoblotting.

Protein Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

Isolated glomeruli were dissolved in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-hydrochloride, pH 7.5; 150 mM sodium chloride; 1% SDS; and protease inhibitor cocktail; Pierce, Rockford, IL). After shearing with a 23-gauge needle, lysates (containing 20 μg total protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, followed by blocking with 3% nonfat milk, incubation with primary antibodies (diluted 1:1000) and horseradish peroxidase–labeled secondary antibody (diluted 1:5000), and exposure to an ECL Hyperfilm (Amersham). Molecular mass was determined relative to protein markers (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy on Cryostat Sections

Freshly dissected kidneys were rapidly frozen using Leica Cryostat (model CM1950) to −20°C and sectioned into 6 μm thin sections. The cryostat sections were fixed with cold methanol for 30 minutes at –20°C, followed by blocking with PBS containing 10% FBS, and incubation with primary antibodies (diluted 1:300) and FITC- or rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies (diluted 1:200). After washing with PBS, slides were mounted with Mowiol (CalBiochem). Epifluorescence images were collected with a Nikon 80i photomicroscope equipped with a DS-Qi1Mc digital camera.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and perfused with 20 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). The perfused kidney was minced into 1 mm3 pieces, and cortical pieces were selected and stored at 4°C overnight in fixative solution. Following fixation, kidney pieces were rinsed with three exchanges of cacodylate buffer over a 1-hour period and then osmicated for 1 hour in 1% osmium tetroxide prepared in cacodylate buffer, rinsed two times over 20 minutes in cacodylate buffer, and then washed with distilled water (dH2O) for 10 minutes followed by en bloc staining with 1% uranyl acetate/water for 60 minutes. After three dH2O rinses, kidney pieces were dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in Araldite resin. The 75 nm ultrathin sections were cut on a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome, picked up on formvar coated grids, and poststained with 1% uranyl acetate/dH2O and Reynolds lead citrate. Sections were viewed on a JEM-1400 transmission microscope (JEOL) at 80 KV with an AMT XR111 4k digital camera.

Quick-Freeze Deep-Etch Electron Microscopy

Quick-freeze deep-etch EM was performed according to published protocol, with minor modifications.65 Freshly dissected mouse kidney cortexes were frozen by abrupt application of the sample against a liquid helium-cooled copper block with a Cryopress freezing machine. Frozen samples were transferred to a liquid nitrogen-cooled Balzers 400 vacuum evaporator, fractured, and etched at –104°C for 2.5 minutes, then rotarily replicated with approximately 2 nm platinum, deposited from a 20° angle above the horizontal plane, followed by an immediate (approximate) 10 nm stabilization film of pure carbon deposited from an 85° angle. Replicas were floated onto a dish of bleach and transferred through several rinses of dH2O, picked up onto formvar-coated grids, and imaged on a JEM1400 transmission microscope (JEOL) at 80 KV with an attached AMT XR111 4k digital camera.

Statistical Analyses

The significance of differences between groups was tested by ANOVA (Statistica 6.0; Statsoft). When the all-effects F value was significant (P<0.05), post hoc analysis of differences between individual groups was made with the Newman–Keuls test. Values were expressed as mean±SEM, unless otherwise stated.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joan Brugge (Harvard Medical School), Dr. Britta Engelhardt (University of Bern, Switzerland), and Dr. Jeffrey Miner (Washington University St. Louis) for kindly providing cell and animal models. We thank Dr. John Heuser (Washington University St. Louis) for kindly providing guidance on freeze-fracture experiments. We thank the electron microscopy cores from Washington University St Louis and Harvard Medical School for assistance with electron microscopy imaging. We thank Dr. George Jarad (Washington University St. Louis) for assistance with glomerular isolation. We thank Dr. Eduardo Splatopolsky for assistance with rat experiments. We thank Dr. Jinzhi Wang for animal husbandry.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01DK084059 and P30DK079333 and the American Heart Association grant 0930050N.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015121324/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goodenough DA, Revel JP: A fine structural analysis of intercellular junctions in the mouse liver. J Cell Biol 45: 272–290, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farquhar MG, and Palade GE: Junctional complexes in various epithelia. J Cell Biol 17: 375–412, 1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Scott RP, Quaggin SE: Review series: The cell biology of renal filtration. J Cell Biol 209: 199–210, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehtonen S, Ryan JJ, Kudlicka K, Iino N, Zhou H, Farquhar MG: Cell junction-associated proteins IQGAP1, MAGI-2, CASK, spectrins, and alpha-actinin are components of the nephrin multiprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 9814–9819, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quaggin SE, Kreidberg JA: Development of the renal glomerulus: good neighbors and good fences. Development 135: 609–620, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grahammer F, Schell C, Huber TB: The podocyte slit diaphragm--from a thin grey line to a complex signalling hub. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 587–598, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kestilä M, Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M, Lamerdin J, McCready P, Putaala H, Ruotsalainen V, Morita T, Nissinen M, Herva R, Kashtan CE, Peltonen L, Holmberg C, Olsen A, Tryggvason K: Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein--nephrin--is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell 1: 575–582, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoshnoodi J, Sigmundsson K, Ofverstedt LG, Skoglund U, Obrink B, Wartiovaara J, Tryggvason K: Nephrin promotes cell-cell adhesion through homophilic interactions. Am J Pathol 163: 2337–2346, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarz K, Simons M, Reiser J, Saleem MA, Faul C, Kriz W, Shaw AS, Holzman LB, Mundel P: Podocin, a raft-associated component of the glomerular slit diaphragm, interacts with CD2AP and nephrin. J Clin Invest 108: 1621–1629, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G, Kaw B, Kurfis J, Rahmanuddin S, Kanwar YS, Chugh SS: Neph1 and nephrin interaction in the slit diaphragm is an important determinant of glomerular permeability. J Clin Invest 112: 209–221, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerke P, Huber TB, Sellin L, Benzing T, Walz G: Homodimerization and heterodimerization of the glomerular podocyte proteins nephrin and NEPH1. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 918–926, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciani L, Patel A, Allen ND, ffrench-Constant C: Mice lacking the giant protocadherin mFAT1 exhibit renal slit junction abnormalities and a partially penetrant cyclopia and anophthalmia phenotype. Mol Cell Biol 23: 3575–3582, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnabel E, Anderson JM, Farquhar MG: The tight junction protein ZO-1 is concentrated along slit diaphragms of the glomerular epithelium. J Cell Biol 111: 1255–1263, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukasawa H, Bornheimer S, Kudlicka K, Farquhar MG: Slit diaphragms contain tight junction proteins. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1491–1503, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagai M, Yaoita E, Yoshida Y, Kuwano R, Nameta M, Ohshiro K, Isome M, Fujinaka H, Suzuki S, Suzuki J, Suzuki H, Yamamoto T: Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, a tight junction membrane protein, is expressed in glomerular podocytes in the kidney. Lab Invest 83: 901–911, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putaala H, Soininen R, Kilpeläinen P, Wartiovaara J, Tryggvason K: The murine nephrin gene is specifically expressed in kidney, brain and pancreas: inactivation of the gene leads to massive proteinuria and neonatal death. Hum Mol Genet 10: 1–8, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M, McCready P, Lamerdin J, Gribouval O, Niaudet PM, Antignac C K, Kashtan CE, Homberg C, Olsen A, Kestilä M, Tryggvason K: Structure of the gene for congenital nephrotic syndrome of the finnish type (NPHS1) and characterization of mutations. Am J Hum Genet 64: 51–61, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruotsalainen V, Ljungberg P, Wartiovaara J, Lenkkeri U, Kestilä M, Jalanko H, Holmberg C, Tryggvason K: Nephrin is specifically located at the slit diaphragm of glomerular podocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 7962–7967, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurihara H, Anderson JM, Kerjaschki D, Farquhar MG: The altered glomerular filtration slits seen in puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis and protamine sulfate-treated rats contain the tight junction protein ZO-1. Am J Pathol 141: 805–816, 1992 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roselli S, Heidet L, Sich M, Henger A, Kretzler M, Gubler MC, Antignac C: Early glomerular filtration defect and severe renal disease in podocin-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 24: 550–560, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou J, Rajagopal M, and Yu AS: Claudins and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 479–501, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Koda R, Zhao L, Yaoita E, Yoshida Y, Tsukita S, Tamura A, Nameta M, Zhang Y, Fujinaka H, Magdeldin S, Xu B, Narita I, Yamamoto T: Novel expression of claudin-5 in glomerular podocytes. Cell Tissue Res 343: 637–648, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao L, Yaoita E, Nameta M, Zhang Y, Cuellar LM, Fujinaka H, Xu B, Yoshida Y, Hatakeyama K, Yamamoto T: Claudin-6 localized in tight junctions of rat podocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1856–R1862, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doné SC, Takemoto M, He L, Sun Y, Hultenby K, Betsholtz C, Tryggvason K: Nephrin is involved in podocyte maturation but not survival during glomerular development. Kidney Int 73: 697–704, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Simic P, Sakamaki Y, Minakuchi H, Fujimura K, Hosoya K, Komatsu M, Kaneko Y, Kanda T, Kubota E, Tokuyama H, Hayashi K, Guarente L, Itoh H: Renal tubular Sirt1 attenuates diabetic albuminuria by epigenetically suppressing Claudin-1 overexpression in podocytes. Nat Med 19: 1496–1504, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin X, Suh JH, Go G, Miner JH: Feasibility of repairing glomerular basement membrane defects in Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 687–692, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeiffer F, Schäfer J, Lyck R, Makrides V, Brunner S, Schaeren-Wiemers N, Deutsch U, Engelhardt B: Claudin-1 induced sealing of blood-brain barrier tight junctions ameliorates chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol 122: 601–614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takemoto M, Asker N, Gerhardt H, Lundkvist A, Johansson BR, Saito Y, Betsholtz C: A new method for large scale isolation of kidney glomeruli from mice. Am J Pathol 161: 799–805, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohse T, Chang AM, Pippin JW, Jarad G, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Miner JH, Shankland SJ: A new function for parietal epithelial cells: a second glomerular barrier. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1566–F1574, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gharib SA, Pippin JW, Ohse T, Pickering SG, Krofft RD, Shankland SJ: Transcriptional landscape of glomerular parietal epithelial cells. PLoS One 9: e105289, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farquhar MG, Wissig SL, and Palade GE: Glomerular permeability. I. Ferritin transfer across the normal glomerular capillary wall. J Exp Med 113: 47–66, 1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M: Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 285–293, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Claude P, Goodenough DA: Fracture faces of zonulae occludentes from “tight” and “leaky” epithelia. J Cell Biol 58: 390–400, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Severs NJ: Freeze-fracture electron microscopy. Nat Protoc 2: 547–576, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heuser JE, Salpeter SR: Organization of acetylcholine receptors in quick-frozen, deep-etched, and rotary-replicated Torpedo postsynaptic membrane. J Cell Biol 82: 150–173, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothberg KG, Heuser JE, Donzell WC, Ying YS, Glenney JR, Anderson RG: Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell 68: 673–682, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heuser J: Three-dimensional visualization of coated vesicle formation in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 84: 560–583, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karnovsky MJ, Ryan GB: Substructure of the glomerular slit diaphragm in freeze-fractured normal rat kidney. J Cell Biol 65: 233–236, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeda T, McQuistan T, Orlando RA, Farquhar MG: Loss of glomerular foot processes is associated with uncoupling of podocalyxin from the actin cytoskeleton. J Clin Invest 108: 289–301, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doyonnas R, Kershaw DB, Duhme C, Merkens H, Chelliah S, Graf T, McNagny KM: Anuria, omphalocele, and perinatal lethality in mice lacking the CD34-related protein podocalyxin. J Exp Med 194: 13–27, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuse M, Sasaki H, Tsukita S: Manner of interaction of heterogeneous claudin species within and between tight junction strands. J Cell Biol 147: 891–903, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, Tani K, Yamazaki Y, Tamura A, Ishitani R, Dohmae N, Tsukita S, Nureki O, Fujiyoshi Y: Crystal structure of a claudin provides insight into the architecture of tight junctions. Science 344: 304–307, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou J, Renigunta A, Konrad M, Gomes AS, Schneeberger EE, Paul DL, Waldegger S, Goodenough DA: Claudin-16 and claudin-19 interact and form a cation-selective tight junction complex. J Clin Invest 118: 619–628, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daugherty BL, Ward C, Smith T, Ritzenthaler JD, Koval M: Regulation of heterotypic claudin compatibility. J Biol Chem 282: 30005–30013, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gong Y, Yu M, Yang J, Gonzales E, Perez R, Hou M, Tripathi P, Hering-Smith KS, Hamm LL, Hou J: The Cap1-claudin-4 regulatory pathway is important for renal chloride reabsorption and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E3766–E3774, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, Benessy F, Lee H, Fuchshuber A, Dahan K, Gubler MC, Niaudet P, Antignac C: NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet 24: 349–354, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caulfield JP, Reid JJ, and Farquhar MG: Alterations of the glomerular epithelium in acute aminonucleoside nephrosis. Evidence for formation of occluding junctions and epithelial cell detachment. Lab Invest 34: 43–59, 1976 [PubMed]

- 48.Farquhar MG, and Palade GE: Glomerular permeability. II. Ferritin transfer across the glomerular capillary wall in nephrotic rats. J Exp Med 114: 699–716, 1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Burlington H, Cronkite EP: Characteristics of cell cultures derived from renal glomeruli. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 142: 143–9, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luimula P, Ahola H, Wang SX, Solin ML, Aaltonen P, Tikkanen I, Kerjaschki D, Holthöfer H: Nephrin in experimental glomerular disease. Kidney Int 58: 1461–1468, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hosoyamada M, Yan K, Nishibori Y, Takiue Y, Kudo A, Kawakami H, Shibasaki T, Endou H: Nephrin and podocin expression around the onset of puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis. J Pharmacol Sci 97: 234–241, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farquhar MG, Vernier RL, Good RA: Studies on familial nephrosis. II. Glomerular changes observed with the electron microscope. Am J Pathol 33: 791–817, 1957 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farquhar MG, Vernier RL, Good RA: An electron microscope study of the glomerulus in nephrosis, glomerulonephritis, and lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med 106: 649–660, 1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vernier RL, Papermaster BW, Good RA: Aminonucleoside nephrosis. I. Electron microscopic study of the renal lesion in rats. J Exp Med 109: 115–126, 1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shono A, Tsukaguchi H, Yaoita E, Nameta M, Kurihara H, Qin XS, Yamamoto T, Doi T: Podocin participates in the assembly of tight junctions between foot processes in nephrotic podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2525–2533, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S: Claudin-1 and -2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol 141: 1539–1550, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verma R, Kovari I, Soofi A, Nihalani D, Patrie K, Holzman LB: Nephrin ectodomain engagement results in Src kinase activation, nephrin phosphorylation, Nck recruitment, and actin polymerization. J Clin Invest 116: 1346–1359, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azhibekov TA, Wu Z, Padiyar A, Bruggeman LA, Simske JS: TM4SF10 and ADAP interaction in podocytes: role in Fyn activity and nephrin phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C1351–C1359, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wartiovaara J, Ofverstedt LG, Khoshnoodi J, Zhang J, Mäkelä E, Sandin S, Ruotsalainen V, Cheng RH, Jalanko H, Skoglund U, Tryggvason K: Nephrin strands contribute to a porous slit diaphragm scaffold as revealed by electron tomography. J Clin Invest 114: 1475–1483, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koop K, Eikmans M, Baelde HJ, Kawachi H, De Heer E, Paul LC, Bruijn JA: Expression of podocyte-associated molecules in acquired human kidney diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2063–2071, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benigni A, Gagliardini E, Tomasoni S, Abbate M, Ruggenenti P, Kalluri R, Remuzzi G: Selective impairment of gene expression and assembly of nephrin in human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 65: 2193–2200, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rincon-Choles H, Vasylyeva TL, Pergola PE, Bhandari B, Bhandari K, Zhang JH, Wang W, Gorin Y, Barnes JL, Abboud HE: ZO-1 expression and phosphorylation in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 55: 894–900, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smithies O: Why the kidney glomerulus does not clog: a gel permeation/diffusion hypothesis of renal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 4108–4113, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harkin JC, and Recant L: Pathogenesis of experimental nephrosis electron microscopic observations. Am J Pathol 36: 303–29, 1960 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Heuser JE, Kirschner MW: Filament organization revealed in platinum replicas of freeze-dried cytoskeletons. J Cell Biol 86: 212–234, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.