Survival rates of childhood cancer have increased over past decades, but around 25% of children diagnosed with cancer eventually die.1 The majority of children with cancer die at home,2 highlighting the role of community healthcare professionals, particularly GPs, in caring for children with advanced cancer. Although GPs are confronted with palliative care for adults on a regular basis, the death of a child with cancer is rare.

WHAT IS PAEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined paediatric palliative care as: ‘the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family. It begins when illness is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease. Health providers must evaluate and alleviate a child’s physical, psychological, and social distress. Effective palliative care requires a broad multidisciplinary approach that includes the family and makes use of available community resources; it can be successfully implemented even if resources are limited. It can be provided in tertiary care facilities, in community health centres and even in children’s homes.’3

LEARNING FROM ADULT PALLIATIVE CARE

A systematic review showed that patients value the involvement of GPs in palliative care for adults: they play a key role in providing continuity of care, they know the family very well, and fulfil a coordinating role in palliative care at home. In general, GPs deliver high-quality palliative care.4 Reported difficulties are about managing the patients’ symptoms, especially those symptoms that are very difficult to treat, or that rarely occur.4,5

As well as parallels between palliative care for adults and paediatric palliative care, there are also differences.6 Children suffer from different types of cancer, and consequently there are differences in symptoms and suffering.7 Other important differences are the developmental stage of the child, communication about death and dying, and psychological factors.8–10 Children have a different understanding of death compared with adults.8 Himelstein et al previously described the stages of development of the concept of death in children, which is relevant for GPs.8 Communication with children with cancer about death and dying may be difficult, as parents and/or healthcare professionals may fear upsetting the child.9,10 Such concern may be unnecessary: research has shown that parents who talked with their child with incurable cancer about death and dying tend not to regret such communication, whereas parents who did not talk tend to regret not doing so.9,10 Lastly, paediatric palliative care, more so than adult palliative care, focused on families, involving not only parents but also siblings and other family members.8

THE ROLE OF GENERAL PRACTICE

Charlton states: ‘Palliative or end-of-life care is very much the domain of the generalist and not the specialist.’11 A study on adult palliative care patients showed that active involvement of GPs during the palliative phase facilitates the possibility of dying at home.12 In the paediatric setting, most children and their parents prefer to stay at home during the palliative phase.2,13 Hynson et al described advantages for the child and family of being at home, such as privacy, the presence of siblings, and parents feeling in control.13

PROVIDING CONTINUITY OF CARE

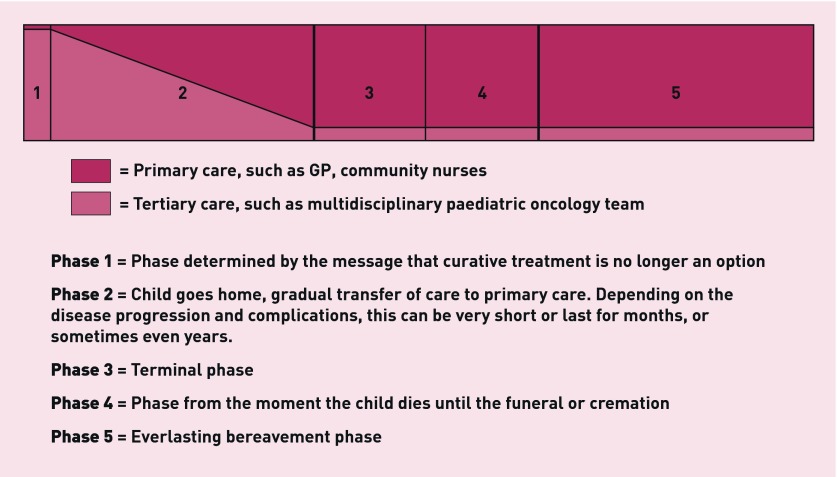

Parents highly value continuity of care.14 Moreover, continuity of care is positively associated with parental long-term psychological functioning.14 GPs can play an essential role in providing this.4 To meet these expectations, GPs should be involved in care from the onset a child receives the diagnosis of childhood cancer to bridge the gap between highly specialised care and community healthcare professionals.13 A systematic review on palliative care for adult patients highlights the need to clarify roles of the involved healthcare professionals.15 When it becomes clear that a child cannot be cured and home is the preferred place of death, the paediatric oncologist and responsible GP should meet and make arrangements, in particular concerning who is primarily responsible for the child’s care. At this stage, care can gradually be handed over to the GP (Figure 1). Close collaboration between GPs and community nurses is crucial.

Figure 1.

Phases of palliative care.

COMMUNICATION RECOMMENDATIONS

Previous studies have stressed the importance of open and honest communication in paediatric palliative care.14 Parents’ long-term level of grief is positively influenced by good communication during the paediatric palliative phase.14 Facilitators for improving communication between the GP and adult palliative care patients that may also be important in a paediatric setting include, for example: being accessible and available; taking time; listening carefully; talking in non-medical language; and being honest and straightforward.16

OPTIMAL SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

Children with cancer at the end of life often suffer from symptoms such as fatigue, pain, dyspnoea, and poor appetite.7 Despite the efforts of healthcare professionals, treatment is not always successful.7 One of the challenges in optimal symptom management is assessing the presence and severity of the child’s symptoms. Children are not always able to indicate to what extent they suffer because of their age or because they cannot always communicate clearly. If children are unable to communicate, parents can be involved and can be a proxy to estimate the child’s level of suffering, taking nonverbal cues of the child into consideration. Also, prescribing medication requires that GPs are familiar with dosage calculation and application schemes for children. There are several national guidelines available for symptom management during the paediatric palliative phase, although a lot remains unknown.17 Further, the effect of symptom management should be evaluated by the GP. Although this may seem obvious, this is often lacking in clinical practice. To support GPs, especially in palliative care for children, consultation-based contact with a (specialised) hospital-based paediatric palliative care team might be helpful.

ADEQUATE BEREAVEMENT CARE

The loss of a child is associated with long-term psychological problems, and parents are at increased risk for traumatic grief.14 Parents’ experiences with the provided paediatric palliative care are associated with the long-term level of grief.14 In particular, the severity of the child’s symptoms and uncontrolled pain are associated with higher levels of grief, whereas good communication and continuity of care are associated with lower levels.14 Alongside the impact for parents, the child’s death also affects siblings.18 Attention after the child’s death is often focused at parents (the main caregivers for their child); consequently, siblings can feel abandoned.18 In a previous study on the wellbeing of bereaved siblings of children with cancer we showed that the death of a child may have negative consequences for bereaved siblings, even after many years.18 Support for siblings should be better organised.18 GPs play an important role in follow-up of parents and siblings, and, if necessary, in referring them to other healthcare professionals.

A NEED TO EDUCATE GPs?

GPs should have knowledge of providing basic (paediatric) palliative care at home. But as the death of a child is rare, training GPs in complex and highly variable situations of paediatric palliative care is not very efficient. GPs should be aware of the available resources for expert advice, which requires good collaboration among healthcare professionals. Consultation-based contact with a (specialised) hospital-based palliative care team that is also available during out-of-hours may be an efficient approach.15

CONCLUSION

Many aspects of paediatric palliative care are similar to adult palliative care. However, the emotional impact of a child dying of cancer is enormous both for the GP and the family.19 Although it happens rarely during a GP’s career, it is a memorable event.19 Continuity of care and facilitated collaboration between hospital and primary care, and between primary healthcare professionals, are essential. A consultation-based contact with a specialised palliative care team to support the GP can be helpful.

Provenance

Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5 — a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):35–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vickers J, Thompson A, Collins GS, et al. Place and provision of palliative care for children with progressive cancer: a study by the Paediatric Oncology Nurses’ Forum/United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Palliative Care Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4472–4476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization WHO Definition of palliative care. 1998. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 10 Nov 2016).

- 4.Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2002;16(6):457–464. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm573oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grande GE, Barclay SI, Todd CJ. Difficulty of symptom control and general practitioners’ knowledge of patients’ symptoms. Palliat Med. 1997;11(5):399–406. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muckaden M, Dighe M, Balaji P, et al. Paediatric palliative care: theory to practice. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17(Suppl):S52–S60. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.76244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1752–1762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Geest IM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van Vliet LM, et al. Talking about death with children with incurable cancer: perspectives from parents. J Pediatr. 2015;167(6):1320–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlton R. Viewpoint — the demise of palliative care. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(536):247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neergaard MA, Vedsted P, Olesen F, et al. Associations between home death and GP involvement in palliative cancer care. Br J Gen Pract. 2009 doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hynson JL, Gillis J, Collins JJ, et al. The dying child: how is care different? Med J Aust. 2003;179(6 Suppl):S20–S22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Geest IM, Darlington AS, Streng IC, et al. Parents’ experiences of pediatric palliative care and the impact on long-term parental grief. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(6):1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Factors supporting good partnership working between generalist and specialist palliative care services: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X641474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slort W, Blankenstein AH, Deliens L, van der Horst HE. Facilitators and barriers for GP-patient communication in palliative care: a qualitative study among GPs, patients, and end-of-life consultants. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X567081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Together for Short Lives and The Rainbows Hospice for Children and Young Adults. Basic symptom control in paediatric palliative care. 2016. http://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/professionals/resources/2434_basic_symptom_control_in_paediatric_palliative_care_free_download (accessed 10 Nov 2016).

- 18.van der Geest IM, Darlington AS, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Re: Long-term psychosocial outcomes among bereaved siblings of children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(5):e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Geest IM, Bindels PJ, Pluijm SM, et al. Home-based palliative care for children with incurable cancer: long-term perspectives of and impact on general practitioners. J Pain Symptom Manage. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.012. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]