Abstract

Background

Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) is a common primary care infection, but there have been no recent, comprehensive diagnostic meta-analyses.

Aim

To determine the accuracy of laboratory and imaging studies for the diagnosis of ARS.

Design and setting

Systematic review of diagnostic tests in outpatient, primary care, and specialty settings.

Method

The authors included studies of patients presenting with or referred for suspected ARS, and used bivariate meta-analysis to calculate summary estimates of test accuracy and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The authors also plotted summary ROC curves to explore heterogeneity, cutoffs, and the impact of different reference standards.

Results

Using antral puncture as the reference standard, A mode ultrasound (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] 1.71, negative likelihood ratio [LR−] 0.41), B mode ultrasound (LR+ 1.64, LR− 0.69), and radiography (LR+ 2.01, LR− 0.28) had only modest accuracy. Accuracy was higher using imaging as the reference standard for both ultrasound (LR+12.4, LR− 0.35) and radiography (LR+ 9.4, LR− 0.27), although this likely overestimates accuracy. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) both had clear threshold effects, and modest overall accuracy. The LR+ for ESR >30 and >40 were 4.08 and 7.40, respectively. A dipstick of nasal secretions for leucocyte esterase was highly accurate (LR+ 18.4, LR− 0.17) but has not been validated.

Conclusion

In general, tests were of limited value in the diagnosis of ARS. Normal radiography helps rule out sinusitis when negative, whereas CRP and ESR help rule in sinusitis when positive, although, given their limited accuracy as individual tests, they cannot be routinely recommended. Prospective studies integrating signs and symptoms with point-of-care CRP, dipstick, and/ or handheld B-mode ultrasound are needed.

Keywords: acute sinusitis, acute rhinosinusitis, clinical diagnosis, clinical decision-making, primary care, rhinosinusitis, sinusitis

INTRODUCTION

Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) accounts for more than 30 million outpatient visits per year in the US.1 It is defined as inflammation of the paranasal sinuses caused by viral or bacterial infection, and typically presents with facial pain or pressure, purulent nasal discharge, fever, cacosmia or hyposmia, and double-sickening (symptoms that worsen after an initial improvement).2 Although most episodes of ARS are viral, they may also be caused by a bacterial infection.3 A Cochrane review concluded that, in patients diagnosed with ARS based on signs and symptoms, antibiotics increased the likelihood of a cure at 7 to 14 days (number needed to treat = 18), although this was balanced by an increased risk of adverse events (number needed to harm = 8).4 Physicians often treat ARS with antibiotics based on the history and the physical examination, resulting in the widespread use of antibiotics for what is predominantly a viral condition.3 Recent guidelines recommend that clinicians only prescribe antibiotics when acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) is suspected because it persists for at least 10 days, or based on double-sickening.3

One strategy to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use is to encourage the use of point-of-care tests such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or imaging to improve diagnostic accuracy. Use of CRP has been shown to reduce antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory tract infections.5 However, practice guidelines generally recommend against the use of imaging because the accuracy of radiography is thought to be poor, ultrasound and radiography are not widely available in the primary care setting, and computed tomography (CT) is expensive and results in potentially harmful radiation exposure.6 In addition, imaging primarily detects fluid in the sinuses and may not distinguish bacterial from viral sinusitis.3,7–9 Antral puncture is the preferred reference standard test, but is not widely used due to the discomfort it causes and a lack of expertise in performing antral puncture in the primary care setting.

Previous systematic reviews have been limited by focusing only on children,10,11 have not identified all relevant studies,11 or are ≥10 years old.10,12 The goal of the current study is to perform an updated, comprehensive systematic review of the accuracy of imaging and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of ARS and ABRS.

METHOD

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The authors included studies of adults and children with clinically suspected sinusitis or acute respiratory tract infection that reported the accuracy of at least one blood test or imaging study for ARS or ABRS. Acceptable reference standards included radiography, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for ARS, and antral puncture revealing purulent fluid or fluid yielding a positive culture for ABRS. Only studies in which all patients received the same reference standard were included, to avoid verification bias. Studies involving hospitalised patients or that recruited patients from highly specialised populations (for example, patients with immunodeficiency, odontogenic sinusitis, or children with brain cancer) were excluded. The authors did not impose any temporal or language limits. Case-control studies were excluded.

How this fits in

This report represents the most comprehensive and methodologically-rigorous systematic review to date of laboratory and imaging studies to diagnose acute rhinosinusitis (ARS). When clinically suspected, the prevalence of sinusitis is approximately 50%. The authors found that C-reactive protein >20 mg/L (LR+ 2.9) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate >30 (LR+4.1) or >40 (LR+ 7.4) significantly increase the likelihood of ARS, whereas normal radiography decreases the likelihood of ARS somewhat (LR− 0.28). The accuracy of ultrasound varied depending on whether it was A or B mode technology, and on the reference standard. B mode ultrasound using antral puncture as the reference standard was not helpful (LR+ 1.6, LR− 0.69). Given the limitations of the evidence base, imaging cannot be routinely recommended for patients with suspected ARS.

In studies that reported findings separately by maxillary, frontal, or ethmoid sinus, only maxillary sinus findings are shown. Whenever individual sinuses as well as results by person are reported, diagnostic accuracy and prevalence are reported by person where possible. Whenever it was possible to use different thresholds (definitions of abnormal) for a test, the threshold that yielded the highest diagnostic odds ratio (DOR, calculated by dividing the positive likelihood ratio [LR+] by the negative likelihood ratio [LR−]) was selected.

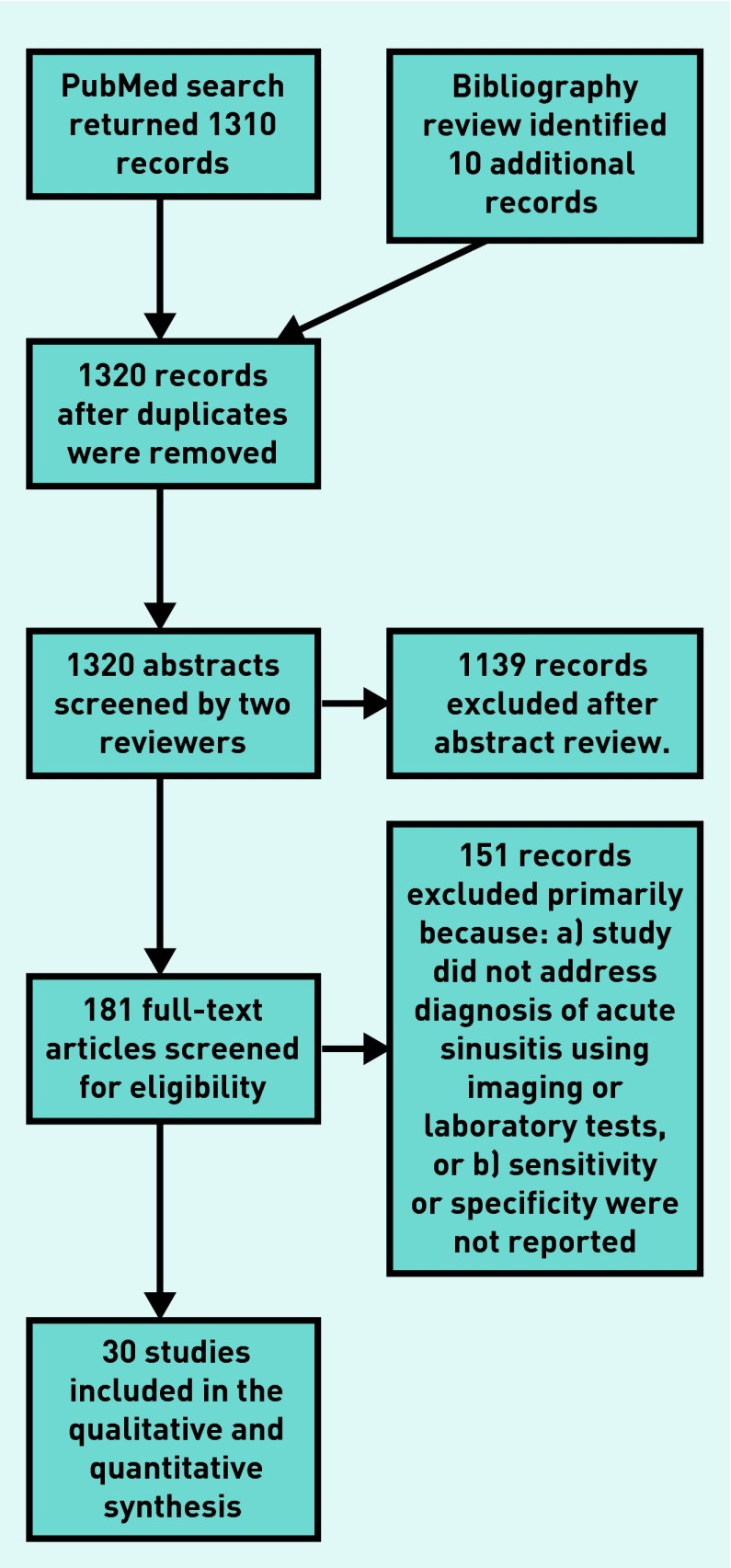

Search strategy and data abstraction

The authors used the strategy shown in Appendix 1 to search MEDLINE®. The reference lists of previous meta-analyses, review articles, and practice guidelines for additional articles were also searched. All abstracts were reviewed by at least two investigators, and any article deemed potentially useful by either investigator was reviewed in full. Full articles were also each reviewed by at least two investigators, who evaluated them for inclusion criteria. Two investigators abstracted data regarding study quality and test accuracy. Any disagreements regarding inclusion criteria, quality, or accuracy were resolved via consensus discussion with the principal investigator. The PRISMA flow diagram describing the search is shown in Appendix 2.

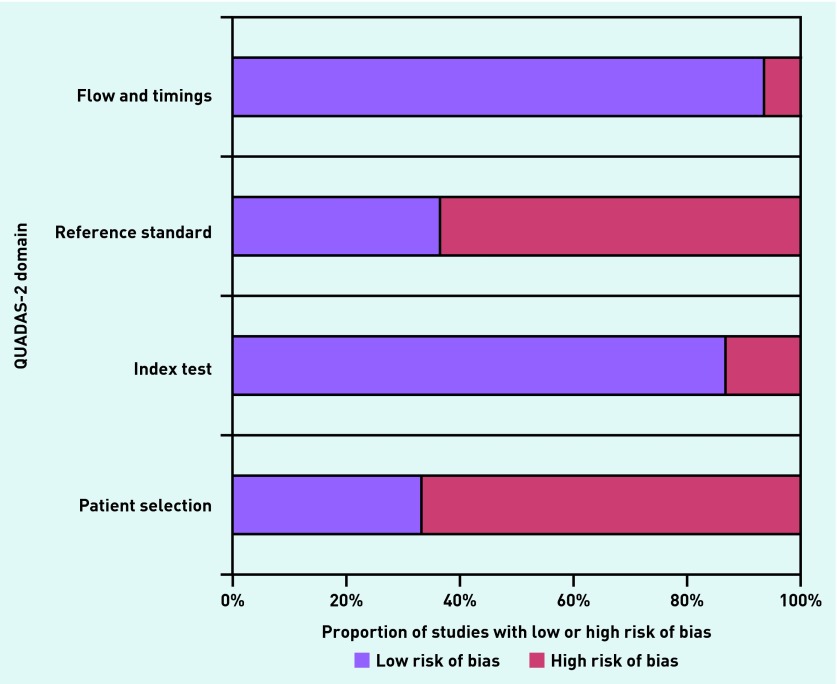

Quality assessment

The authors adapted the QUADAS-2 criteria for the study (Appendix 3).13 Quality assessment was done in parallel by two investigators, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus discussion.

Analytic strategy

The metaprop procedure in R version 3.2.2 was used to perform random effects meta-analysis of the prevalence of sinusitis, stratified by age group, clinical presentation, and reference standard. The authors used the meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy (mada) procedure in R version 3.2.2 to perform bivariate meta-analysis for each test using the Reitsma procedure, stratified by imaging technology and reference standard where appropriate. Summary measures of sensitivity, specificity, LR+, and LR− are reported. Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn to explore sources of heterogeneity and threshold effects for key tests, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated for selected tests. Formal testing for heterogeneity was not performed, as it is unreliable when there are small numbers of studies,14 and in particular for diagnostic meta-analysis as it does not account for threshold effects. For example, sensitivity and specificity vary inversely as the threshold for diagnosis changes, often implicitly, and do not necessarily represent heterogeneity of populations.15

RESULTS

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are summarised in Appendix 4. The authors identified a total of 30 studies, 16 enrolling adults,16–31 eight both adults and children,32–39 four enrolling only children,40–43 and two that did not report the age of participants.44,45 Two were retrospective cohort studies,36,44 and the remainder were prospective cohort studies. Two studies enrolled patients with the common cold or a ‘runny nose’,30,40 while the remaining 28 enrolled patients with clinically suspected acute sinusitis. Only four studies were at a low overall risk of bias.19,20,23,40 The remainder were at moderate (n = 11) or high (n = 9) overall risk of bias (Appendix 5).

The authors identified studies of the accuracy of imaging including radiography, screening coronal computed tomography, and ultrasound (both A and B mode). A mode ultrasound is amplitude modulation and is no longer in wide use, whereas B mode or brightness modulation is the more commonly used two-dimensional study. Blood tests studied included CRP, white blood cell count (WBC), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and other tests included rhinoscopy, a test of nasal secretions, and the accuracy of scintigraphy.

Prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis

The prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis in the included studies is summarised in Table 1 (a more complete version of these results are shown in Appendix 6). It is stratified by population, reference standard, and presenting symptoms. In studies enrolling adults, or a mix of adults and children with clinically suspected acute rhinosinusitis, the prevalence ranged from 16% to 80%, with a pooled prevalence of 48% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 42 to 54). There was no significant difference in prevalence by type of reference standard (antral puncture, radiography, or CT). Studies in children with clinically suspected rhinosinusitis had prevalences between 19% and 57%, with a pooled prevalence of 41% (95% CI = 19 to 67). Two studies enrolled all patients with a cold or runny nose and found a lower prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis of 20% (95% CI = 14 to 29).30,40

Table 1.

Prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis in the included studies, by population, inclusion criteria, and reference standarda

| Population | Reference standard | Patients, n (studies, n) | Prevalence of ARS, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults or adults and children with clinically suspected ARS | Antral puncture | 1971 (11) | 49 (42 to 57) |

| Adults or adults and children with clinically suspected ARS | CT | 487 (5) | 44 (23 to 67) |

| Adults or adults and children with clinically suspected ARS | Rad | 1345 (9) | 48 (39 to 57) |

| Adults with acute respiratory tract infection | AP (1), MRI (1) | 501 (2) | 20 (14 to 29) |

| All studies in adults | 49 (43 to 55) | ||

| All studies in children | CT (1), Rad (2) | 260 (3) | 41 (19 to 67) |

| All studies in adults and children | 47 (41 to 53) |

If a study reports different numbers of patients with different signs and symptoms, the data for the greatest number of patients reported were used.

AP = antral puncture revealing purulence. ARS = acute rhinosinusitis. CT = computed tomography. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. Rad = radiography.

Accuracy of imaging

The accuracy of imaging studies is summarised in Table 2 (Appendix 7). Because there was no clear pattern of accuracy with regard to studies of children and adults, and due to the small number of studies in children, their results are combined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracy of imaging studies for acute rhinosinusitis

| Test | Reference standard | Patients, n (studies, n) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiography | AP | 1564 (9) | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.90) | 0.56 (0.38 to 0.73) | 2.01 (1.40 to 3.05) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.39) | 0.820 |

| Radiography | Imaging | 350 (3) | 0.80 (0.66 to 0.89) | 0.84 (0.31 to 0.98) | 9.37 (1.27 to 39.6) | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.48) | 0.841 |

| Radiography | Any | 1914 (12) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.89) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.78) | 2.36 (1.57 to 3.68) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.34) | 0.836 |

| Radiographya | Any | 1592 (9) | 0.82 (0.74 to 0.88) | 0.69 (0.45 to 0.86) | 2.96 (1.51 to 5.7) | 0.27 (0.19 to 0.37) | 0.84 |

| Ultrasound, A mode | AP | 552 (4) | 0.79 (0.52 to 0.93) | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.71) | 1.71 (1.42 to 2.08) | 0.41 (0.19 to 0.68) | 0.679 |

| Ultrasound, B mode | AP | 262 (2) | 0.53 (0.03 to 0.98) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.77) | 1.64 (0.10 to 3.2) | 0.69 (0.03 to 1.36) | 0.693 |

| Ultrasound, A mode | Imaging | 713 (6) | 0.62 (0.55 to 0.69) | 0.91 (0.79 to 0.96) | 7.64 (2.95 to 17.1) | 0.42 (0.32 to 0.54) | 0.702 |

| Ultrasound, B mode | Imaging | 351 (4) | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.81) | 0.98 (0.94 to 0.99) | 38.4 (12.7 to 88.3) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.34) | 0.897 |

| Ultrasoundb | Any | 1060 (8) | 0.68 (0.45 to 0.85) | 0.72 (0.50 to 0.87) | 2.58 (1.4 to 4.6) | 0.46 (0.22 to 0.73) | 0.76 |

| Limited CT scan | CT | (2) | 0.88 (0.71 to 0.96) | 0.89 (0.77 to 0.95) | 9.01 (3.77 to 18.3) | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.33) | 0.895 |

Radiography, excluding studies at high risk of bias.

Ultrasound, excluding studies at high risk of bias.

AP = antral puncture showing purulent fluid. AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. CT = computed tomography. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio.

The most accurate imaging test was limited or screening CT (LR+ 9.01, LR− 0.15, AUC 0.895), but was only evaluated in two small studies at high risk of bias that used full CT as the reference standard.36,44 Radiography was fairly sensitive when compared with antral puncture, but lacked specificity, and was therefore more helpful when negative (LR− 0.28) than when positive (LR+ 2.01). Figure 1a shows a summary ROC curve for radiography.

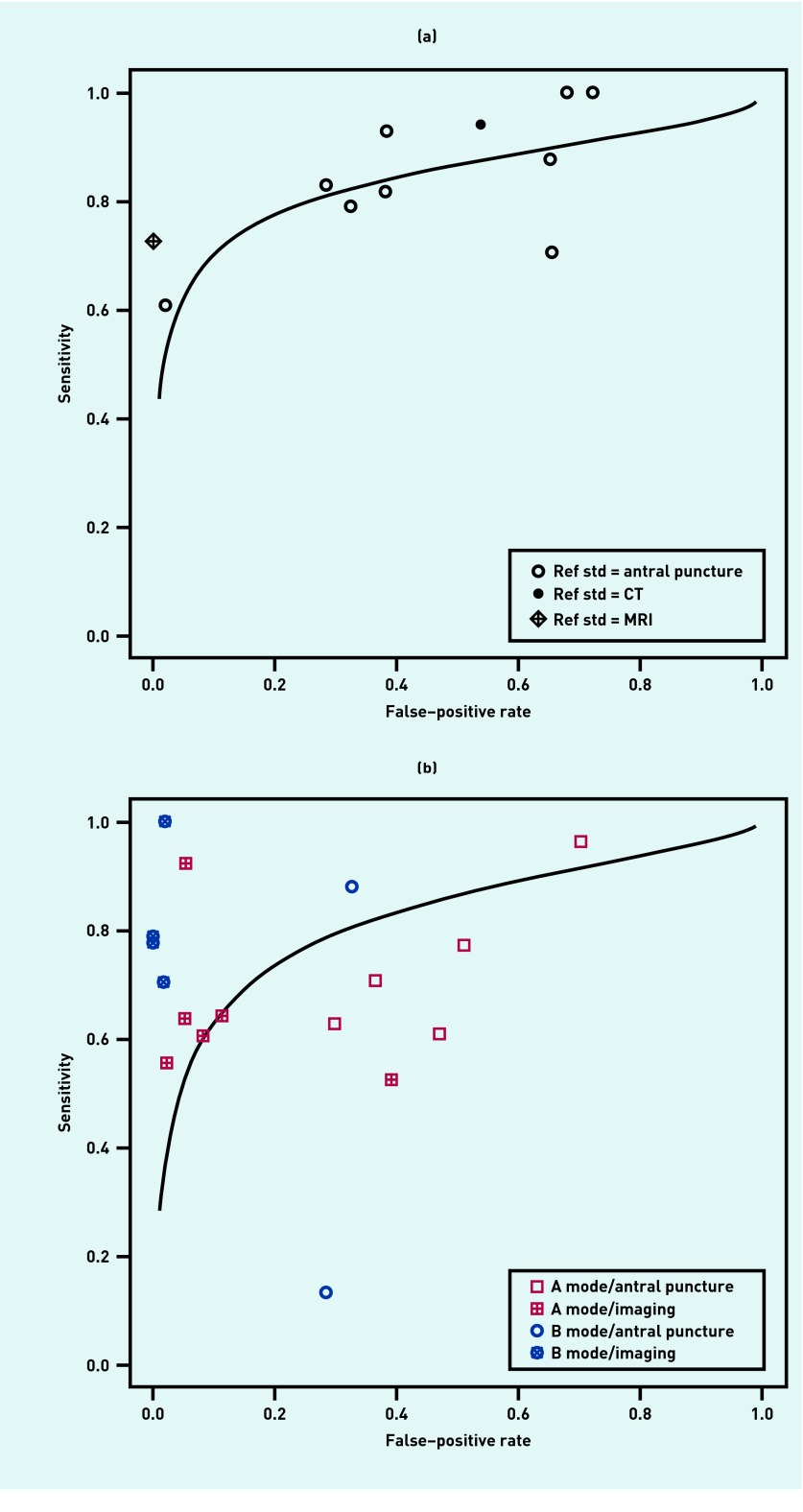

Figure 1.

(a) Summary receiver operating characteristic curve for radiography, with accuracy stratified by the reference standard. (b) Summary receiver operating characteristic curve for ultrasound, with accuracy stratified by the reference standard for A and B mode. CT = computed tomography. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. Ref std = reference standard.

The accuracy of ultrasound varied depending on the mode (A or B) and the reference standard (antral puncture or imaging). In general, B mode was more accurate than A mode, and studies using antral puncture as the reference standard found much lower accuracy (particularly specificity) than those using imaging. Using antral puncture as the reference standard, both A mode (LR+ 1.71, LR− 0.41, AUC 0.679) and B mode (LR+ 1.64, LR− 0.69, AUC 0.693) ultrasound had only modest accuracy. Figure 1b shows a summary ROC curve for ultrasound, stratified by mode and reference standard.

A sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias found no significant difference regarding the accuracy of radiography (LR+ 2.88, LR− 0.27). High-quality studies of ultrasound had a positive likelihood ratio of 2.58 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.46, reflecting the fact that antral puncture was used as the reference standard rather than imaging.

Accuracy of laboratory tests

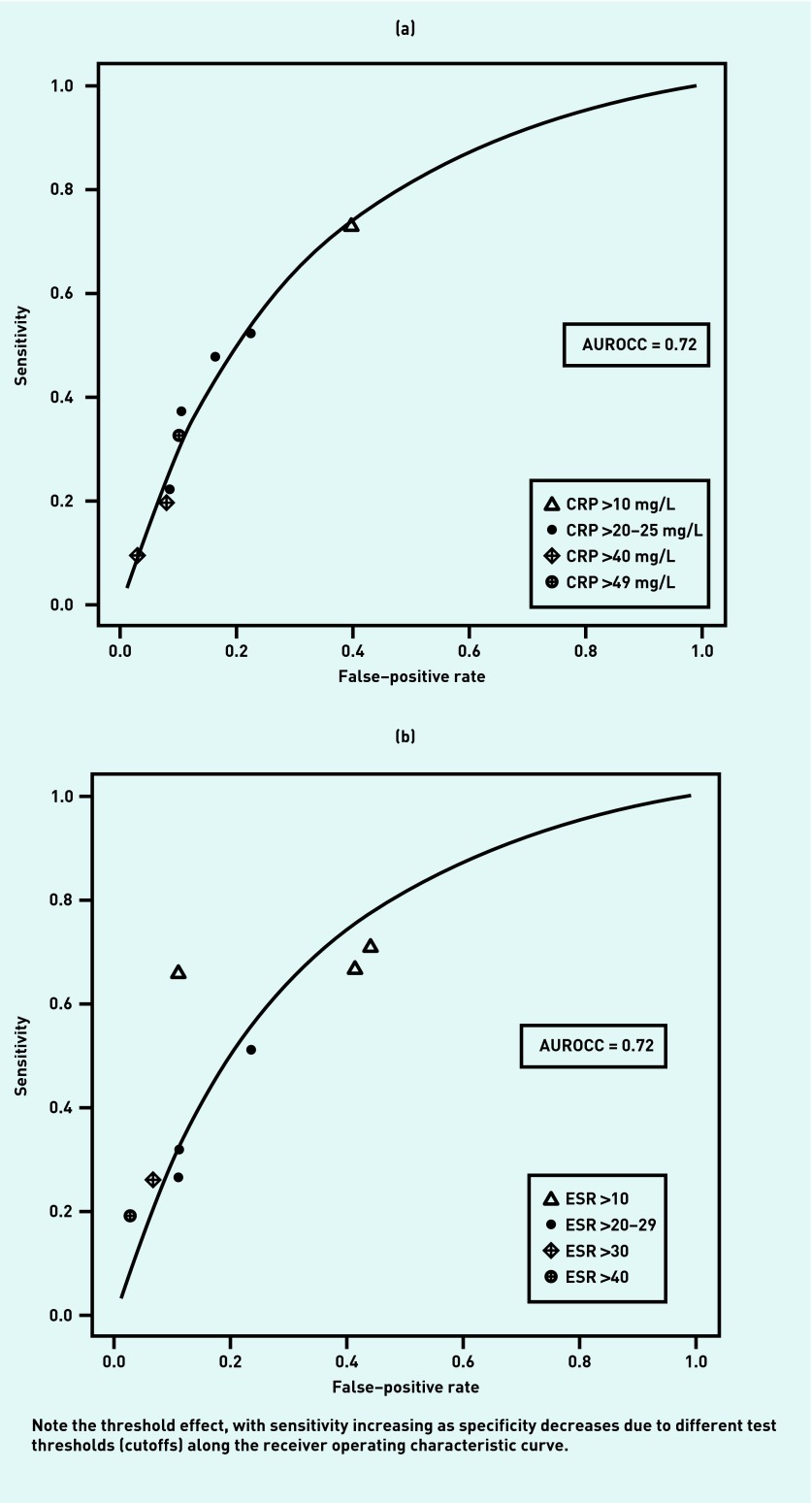

The accuracy of blood tests and other tests for ARS are shown in Table 3 (study-level data shown in more detail are available from the authors). Summary ROC curves for CRP and ESR are shown in Figures 2a and 2b. Both show clear threshold effects. That is, differences in accuracy are likely to be related to differences in the cutoff or threshold. It was therefore not appropriate to calculate a summary estimate of accuracy for these tests as a group. An ESR <10 is limited evidence against a diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis (LR− 0.57), while an ESR >30 (LR+ 4.08) or >40 (LR+ 7.40) provide moderate evidence in favour of the diagnosis. Similarly, a CRP <10 mg/L was limited evidence against a diagnosis of ARS (LR− 0.45), while a CRP >20 is limited evidence in favour of the diagnosis (LR+ 2.92). Only one of the four studies of CRP used antral puncture as the reference standard, and it had generally similar results to the imaging studies.19

Table 3.

Accuracy of blood tests for the diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis in adultsa

| Test | Total patients, nreference | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | DOR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood tests | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| CRP | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| CRP >10 mg/L | 17319 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 1.84 | 0.45 | 4.09 | |

| CRP >20–25 mg/L | 78919,21,24,29 | 0.39 (0.29 to 0.50) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.91) | 2.92 (2.17 to 3.98) | 0.71 (0.60 to 0.80) | 4.11 | |

| CRP >40–49 mg/L | 54819,21,24 | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.30) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.95) | 2.46 (1.45 to 3.91) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.93) | 2.86 | |

| Summary | 0.34 (0.21 to 0.51) | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.94) | 2.92 (2.21 to 3.80) | 0.74 (0.60 to 0.85) | 3.95 | 0.720 | |

| ESR | |||||||

| ESR >10 | 42619,21,24 | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.72) | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.65) | 1.60 (1.33 to 1.97) | 0.57 (0.46 to 0.68) | 2.81 | |

| ESR >20 | 42519,23,24 | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.51) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.92) | 2.55 (1.68 to 3.74) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.85) | 3.45 | |

| ESR >30 | 16819 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 4.08 | 0.79 | 5.16 | |

| ESR>40 | 17621 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 7.40 | 0.83 | 8.91 | |

| Summary | 0.43 (0.29 to 0.58) | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.92) | 2.61 (1.85 to 3.68) | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.78) | 3.84 | 0.685 | |

|

| |||||||

| WBC | |||||||

| WBC >10 | 37521,24 | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.31) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.93) | 2.23 (1.29 to 3.66) | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.94) | 2.62 | 0.710 |

| Other tests | |||||||

| Clinical nasal secretion score ≥4 | 21739 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 95 | 0.05 | 1900 | |

| Leucocyte esterase ≥1+ | 21739 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 18.4 | 0.17 | 108 | |

| Protein >2.0 | 21739 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 4.5 | 0.05 | 91 | |

| Nitrite >1.0 | 21739 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 7.6 | 0.52 | 14.7 | |

| pH >7 | 21739 | 0.96 | 0.42 | 1.7 | 0.09 | 18.6 | |

| Leucocytes in sinus washings | 18723 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 3.7 | 0.21 | 17.7 | |

| Leucocytes in sinus washings | 9340 | 0.31 | 0.94 | 4.9 | 0.74 | 6.6 | |

| Leucocytes in nasal secretions | 3041 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 3.1 | 0.08 | 38.3 | |

| Flexible endoscopy | 10425 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 2.5 | 0.26 | 9.7 | |

| Rhinoscopy, pus in nasal cavity | 24129 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 1.3 | 0.47 | 2.8 | |

| Rhinoscopy, pus in throat | 24229 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 1.3 | 0.93 | 1.4 | |

| Scintigraphy (probably or definitely abnl) | 4817 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 11.4 | 0.09 | 127 | |

| Diode gas laser spectroscopy (frontal sinus) | 8031 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 14.1 | 0.15 | 94 | |

| Diode gas laser spectroscopy (maxillary sinus) | 7531 | 0.39 | 0.93 | 5.5 | 0.66 | 8.4 | |

No studies with children were identified. Where results for more than one study are presented, a summary estimate is shown.

Abnl = abnormal. AP = antral puncture revealing purulent fluid. AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. CRP = C-reactive protein. DOR = diagnostic odds ratio (positive likelihood ratio divided by negative likelihood ratio). ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. WBC = white blood cells. (Individual-study level data and the reference standard used for each test is shown in Appendix 8 and Appendix 9)

Figure 2.

(a) Summary receiver operating characteristic curve for the accuracy of C-reactive protein as a test for acute rhinosinusitis. (b) Summary receiver operating characteristic curve for the accuracy of erythrocyte sedimentation rate as a test for acute rhinosinusitis. AUROCC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. CRP = C-reactive protein. ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

A single study evaluated the accuracy of a test strip of the sort ordinarily used for diagnosis of urinary tract infection.39 The researchers found that leucocyte esterase and nitrite were highly specific, while pH and protein were highly sensitive. A score that assigned 0 to 3 points to each of these tests successfully identified patients at low (0%), moderate (33%), and high (100%) risk of ARS. However, this study was at high risk of bias because it used imaging rather than antral puncture as the reference standard, and the thresholds for low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups were established post hoc.

The presence of leucocytes in nasal washings was evaluated in three studies, with LR+ ranging from 3.06 to 4.92, and LR− from 0.08 to 0.74.24,40,41 Rhinoscopy for pus in the nasal cavity or throat (LR+ 1.32, LR− 0.47 to 0.93) and the white blood cell count (LR+ 2.23, LR− 0.85) both lacked accuracy for the diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis.21,24,29

DISCUSSION

Despite being a very common complaint in the outpatient setting, the evidence base for imaging and laboratory tests to diagnose ARS is limited. Many of the studies are ≥20 years old and few are at low risk of bias. Using antral puncture as a reference standard, sinus radiographs are fairly sensitive but have poor specificity. However, they are useful for reducing the likelihood of ARS when negative (LR− 0.28). Although studies comparing ultrasound to imaging (largely radiography) found good accuracy, those using antral puncture as the reference standard found that, like radiography, it lacked specificity. That is likely to be because imaging studies are limited to detection of fluid in the sinuses, which is commonly seen in viral upper respiratory tract infections as well.

Although CT is often recommended as the imaging study of choice for patients with persistent symptoms, chronic sinusitis, or when surgery is being considered,3 the authors identified only two small studies comparing limited or screening CT with full CT of the sinuses,36,44 and no studies directly comparing CT to antral puncture.

C-reactive protein and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate performed similarly as tests for acute rhinosinusitis. In both cases there was no clearly preferred single threshold for defining an abnormal test. A potentially useful strategy would be to define two thresholds and three risk groups, for example, CRP or ESR <10 defining a low-risk group, 10 to 30 a moderate-risk group, and >30 a high-risk group. However, as originally reported in the relevant studies, it is not possible to determine stratum-specific likelihood ratios and predictive values as part of this meta-analysis.

The study by Huang and Small suggests an innovative approach to diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis, using a dipstick normally used for urinalysis.39 It deserves replication, in particular the very promising risk score based on the dipstick findings.

Strengths and limitations

The authors’ conclusions are limited by the relatively poor quality of many studies, many of which are quite old. There was significant unexplained heterogeneity, for example, among studies of radiography using antral puncture as the reference standard, and therefore summary estimates of accuracy should be interpreted cautiously. An unexpected finding was the similar prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis when using antral puncture as the reference standard compared with imaging. Although the authors expected a lower prevalence with antral puncture as the reference standard, because it was presumably largely detecting only ABRS, it may be that the spectrum of patients in the Scandinavian countries where the antral puncture studies were largely performed may be different, with patients not seeking care unless symptoms are more severe.

Strengths of the current study include: an updated and comprehensive search identifying more studies than previous systematic reviews; use of a bivariate meta-analysis; and the use of summary ROC curves to allow a better understanding of heterogeneity due to different reference standard and diagnostic cutoffs.

Implications for research

A condition as common as acute rhinosinusitis deserves a better evidence base. A particular challenge is the choice of a reference standard. Radiography and ultrasound lack specificity, and CT is costly, exposes patients to radiation, and is likely to mistakenly classify many patients with viral respiratory infection as having ARS. Antral puncture revealing purulent fluid is arguably the preferred reference standard. Although some might argue that bacterial culture of antral fluid revealing a bacterial pathogen is the optimal reference standard, cultures may lack sensitivity.

Use of C-reactive protein in particular is promising because it is available as a rapid and relatively inexpensive point-of-care test that has been shown in randomised controlled trials to reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotics for respiratory infections in the primary care setting.46,47 Trials of its use in patients with clinically suspected sinusitis are needed, using clinically helpful cutoffs to identify low-, moderate-, and high-risk patients.

Physicians increasingly have access to high-resolution B mode ultrasound in a handheld device at the point of care.48,49 To date, these devices have not been evaluated for their ability to diagnose ARS. A study evaluating the accuracy of signs and symptoms as well as handheld B mode ultrasound, C-reactive protein, and/or dipstick for leucocyte esterase, nitrite, pH, and protein, and using antral puncture as the reference standard, would be an important contribution to the literature. This could lead to the development and validation of a decision support tool that integrates signs and symptoms with one of these point-of-care tests, to help physicians limit antibiotic therapy to only those patients most likely to benefit.

Appendix 1. Search strategy used in MEDLINE

(rhinosinusitis[Title/Abstract] OR sinusitis[Title/Abstract] OR sinus infection[Title/Abstract] OR sinusitis[MeSH Terms] OR “Paranasal Sinus Diseases”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“medical history taking”[MeSH Terms] OR “physical examination”[MeSH Terms] OR “signs and symptoms”[Title/Abstract] OR “symptoms and signs”[Title/Abstract] OR symptom[Title/Abstract] OR “history and physical” OR ”physical examination” OR “physical exam”[Title/ Abstract] OR “clinical examination”[Title/Abstract] OR ultrasound[Title/Abstract] OR “computed tomogram”[Title/ Abstract] OR “computed tomographic”[Title/Abstract] OR “radiograph”[Title/Abstract] OR “radiographic”[Title/ Abstract] OR “x-ray”[Title/Abstract] OR “computed tomography”[Title/Abstract] OR “radiological”[Title/Abstract] OR “CRP”[Title/Abstract] OR “C-reactive protein”[Title/Abstract] OR “white blood cell count”[Title/Abstract] OR “white cell count”[Title/Abstract] OR“leucocytosis”[Title/Abstract] OR “leucocyte count”[Title/Abstract] OR Westergren”[Title/Abstract] OR “sed rate”[Title/Abstract] OR “sedimentation rate”) NOT (“carotid sinus” OR “sinus rhythm” OR “sinus arrest” OR “aortic sinus” OR “aortic sinuses” OR “cavernous sinus” OR “sinus tachycardia” OR “sinus arrhythmia” OR “cavernous sinuses” OR “sinus tract” OR “sinus tracts” OR “coronary sinus” OR “renalsinus” OR “sinus node” OR “sinusoidal” OR “non-sinus” OR “petrosal sinus” OR “sinus rate” OR “sinus rhythm” OR “sinus cardiac rhythm” OR “sinus cyst” OR “sinusoid”) NOT chronic[Title/Abstract] OR surgery[Title] OR surgical[Title] OR lymphoma OR mycosis OR “sphenoid” OR Wegener’s OR sarcoidosis OR cancer OR postoperative OR myositis OR HIV OR tuberculosis OR fasciitis OR periodontitis OR “dental implant”).

Appendix 2. PRISMA flow diagram of studies selected for meta-analysis.

Appendix 3. QUADAS-2 instrument, adapted for systematic review of the accuracy of signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of acute sinusitisa

| Study, year | QUADAS-2 study design questions | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference std | Flow & timing | Overall | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

| Consecutive | Not case-control | Exclusion criteria | Risk of bias | Applicability | Index blinded | Threshold pre-specified | Risk of bias | Applicability | Antral puncture used | Reference blinded | Risk of bias | Applicability | All got reference standard | All had same ref standard | All accounted for | Risk of bias | L = 0, M = 1, and H = 2+ with high likelihood of bias | |

| Adults | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hansen, 1995 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | L |

| van Buchem, 1995 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | L |

| Laine, 1998 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | L |

| Bergstedt,1980 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Savolainen, 1997a | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Savolainen, 1997b | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Puhakka, 2000 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Young, 2003 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Kuusela, 1983 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | U | Y | H | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Berg, 1981 | N | Y | Y | H | L | U | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Rohr, 1986 | U | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Jensen, 1987 | U | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | U | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Lindbaek, 1996 | U | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | U | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Varonen, 2003 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Berger, 2011 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Lewander, 2012 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Adults and children | ||||||||||||||||||

| Watt-Boolsen, 1977 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Shapiro, 1986 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| McNeill, 1963 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | N | H | L | Y | Y | N | H | H |

| Berg, 1985 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | N | H | H |

| Gianoli,1992 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Ghatasheh, 2000 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | U | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Awaida, 2004 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Huang, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | N | H | L | N | U | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Children | ||||||||||||||||||

| van Buchem, 1992 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | Y | U | L | L | Y | Y | Y | L | L |

| Reilly, 1989 | Y | Y | Y | L | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | M |

| Visca, 1995 | N | Y | U | H | U | Y | U | L | N | Y | U | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Fufezan, 2010 | U | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Not reported | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dobson, 1996 | N | Y | Y | H | L | U | Y | H | L | N | U | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

| Goodman, 1995 | N | Y | Y | H | L | Y | Y | L | L | N | Y | H | L | Y | Y | Y | L | H |

Overall risk of bias was low (L) if all domains were at low risk of bias, moderate (M) if one domain was at high risk of bias, and high (H) if two or more domains were at high risk of bias.

Ref = reference. Std = standard.

QUADAS-2 instrument, adapted for systematic review of the accuracy of signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of acute sinusitis.a Definitions of questions 1–17 for QUADAS-2

Patient selection, questions 1–5

- 1. Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Study enrolled consecutive patients or a random sample of consecutive patients from a primary care, urgent care, or emergency department setting

- N: A convenience sample or other non-consecutive or non-random sample was used, or it only included patients referred for diagnostic imaging or to an ENT clinic (this does not address exclusion criteria, see question 3)

- U: Uncertain

- 2. Was the study designed to avoid a case-control design? (Y/N/U)

- Y: The study population was drawn from a cohort that included patients with a spectrum of disease

- N: The study population consisted of patients with known disease and healthy controls

- U: Uncertain

- 3. Did the study design avoid inappropriate exclusion criteria? (Y/N/U)

- Y: There were no inappropriate exclusion criteria, such as excluding those with uncertain findings

- N: The study used inappropriate exclusion criteria

- U: Uncertain

- 4. Patient selection risk of bias: What is the likelihood that patient selection could have introduced bias? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood of bias due to patient selection or enrolment (‘Yes’ to question 1, 2, and 3)

- H: High likelihood of bias due to patient selection (‘No’ to question 1, 2, or 3)

- U: Unable to judge degree of bias

- 5. Concerns about patient selection applicability: Are there concerns that included patients and setting do not match the review question? (L/H/U)

- L: Low risk of bias — the patients or settings are from the outpatient setting and have clinically suspected acute sinusitis or acute respiratory tract infection

- H: High risk of bias — the patients or settings do not match the review question, for example, a group of patients hospitalised, or from a specialised population, or patients with subacute or chronic sinusitis

- U: Uncertain

Index test, questions 6–9

- 6. Were index test results interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes

- N: No (including when index and reference standard were performed by the same observer, although blinding was not addressed)

- U: Uncertain

- 7. If a threshold was used for the index test, was it pre-specified? (Y/N/U)

- Y: The threshold was pre-specified, or there was no threshold mentioned

- N: The threshold was established post hoc

- U: A threshold was used but it is not clear when it was specified

- 8. Index test risk of bias: What is the likelihood that conduct of the index test could have introduced bias? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood of bias — ‘Yes’ to question 6, and ‘Yes’ or ‘Uncertain’ to question 7

- H: High likelihood of bias due to failure to mask to reference standard — ‘No’ or ‘Uncertain’ to question 6 or ‘No’ to question 7

- U: Uncertain

- 9. Concerns regarding index test applicability: Are there concerns that the index test differs from those specified in the review question? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood — the index test in this study is a laboratory or imaging test

- H: High likelihood — the index test in this study may not be a laboratory or imaging test

- U: Uncertain

Reference standard test, questions 10–13

- 10. Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify patients as having acute sinusitis? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes, used antral puncture

- N: No, used another reference standard

- U: Uncertain

- 11. Was the reference standard interpreted without knowledge of the index test? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes, reference standard interpretation masked to index test results

- N: No, reference standard interpretation not masked to index test results

- U: Uncertain

- 12. Reference standard risk of bias: Could conduct or interpretation of the reference standard have introduced bias? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood of bias due to the reference standard (‘Yes’ to question 9, ‘Yes’ or ‘Uncertain’ to question 10)

- H: High likelihood of bias due to inadequate reference standard (‘No’ to question 9 or 10)

- U: Uncertain

- 13. Concerns regarding applicability of the reference standard: Are there concerns that the target conditions defined by the reference standard do not match the review question? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood of bias — that is, the reference standard was intended to detect acute sinusitis

- H: High likelihood of bias — that is, the reference standard was not intended to detect acute sinusitis

- U: Uncertain

Patient flow and timing, questions 14–17

- 14. Did all patients receive a reference standard? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes, all patients received some sort of reference standard (no partial verification bias)

- N: No, some patients did not receive any reference standard (partial verification bias)

- U: Uncertain

- 15. Did all patients receive the same reference standard? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes, all used the same reference standard (no differential verification bias)

- N: No, the reference standard varied depending on the results of the index test (differential verification bias)

- U: Uncertain

- 16. Were all patients included in the analysis? (Y/N/U)

- Y: Yes, all patients were properly accounted for in the analysis

- N: No, some patients were not accounted for or dropped out for unclear reasons

- U: Uncertain

- 17. Patient flow risk of bias: Could patient flow have introduced bias? (L/H/U)

- L: Low likelihood of bias based on absence of partial verification bias and good follow-up (‘Yes’ to question 14 and 15, ‘Yes’ or ‘Uncertain’ to question 16)

- H: High likelihood of bias based on partial verification bias or poor follow-up (‘No’ to question 14 or 15, or significant number of patients lost to follow-up in question 16)

- U: Uncertain

Appendix 4. Characteristics of included studies, by population and sorted by year of publication (with individual study-level data)

| Study, year | Population | Setting | Number in study | Mean age and/or age range, years | Reference standard | Country | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | |||||||

| Bergstedt, 198017 | Adults with clinically suspected maxillary sinusitis | ENT clinic | 48 | Range 17 to 79 | Antral aspiration showing purulent aspirate | Sweden | NR |

| Berg, 198116 | Adults with clinically suspected sinusitis of at least 3 weeks’ duration | ENT clinic | 50 | Mean age 46 | AP revealing purulent discharge | Sweden | NR |

| Kuusela, 198318 | Young adults (largely male) with clinically suspected acute sinusitis | Military clinic | 105 | NR | AP showing purulent fluid | Finland | NR |

| Rohr, 198627 | Adults with clinically suspected acute sinusitis | Medicine outpatient clinic | 99 | Range 18 to 74 | Radiograph showing mucosal thickening or opacification >4 mm | US | NR |

| Jensen, 198726 | Adults with clinically suspected acute sinusitis | ENT clinic | 138 (253 sinuses) | Mean age 33 | Radiograph showing mucosal thickening >6 mm, fluid, or complete opacification | Sweden | NR |

| Hansen, 1995a19 | Consecutive adults suspected of having acute maxillary sinusitis by their GP | Primary care clinic | 174 | Median 35, range 18 to 65 | CT scan abnormal and purulent or mucopurulent material from AP | Denmark | 1992 to 1994 |

| van Buchem, 199523 | Adults with clinically suspected acute maxillary sinusitis | Primary care with referral to ENT clinic | 113 | 42% 18 to 29, 34% 30 to 44, 16% 45 to 59, and 9% 60 or older | AP showing fluid or floccules | Netherlands | NR |

| Lindbaek, 199624 | Adults clinically diagnosed by a primary care doctor with acute sinusitis requiring antibiotics | Primary care | 201 | Mean 37.8, range 15 to 83 | CT scan showing air-fluid level or complete opacification | Norway | 1993 |

| Savolainen, 199721 | Young adult men with suspected acute maxillary sinusitis <3 weeks’ duration | ENT clinic (military) | 176 | Mean 20.5 | AP with positive bacterial culture | Finland | NR |

| Savolainen, 199722 | Young adult men with suspected acute maxillary sinusitis <30 days’ duration | ENT clinic (military) | 161 (322 sinuses) | Mean 29, range 17 to 68 | AP yields fluid | Finland | NR |

| Laine, 199820 | Consecutive adult patients with clinically suspected acute maxillary sinusitis, duration <30 days | Primary care clinic | 39 | Median 37, range 16 to 68 | Nasal aspirate with purulent or mucopurulent material | Finland | 1992 to 1993 |

| Puhakka, 2000b30 | Convenience sample of young adult students with symptoms of common cold <48 hours | Primary care clinic | 200 (394 sinuses) | Mean 24 | MRI using same criteria for accuracy of ultrasound and radiographs | Finland | NR |

| Young, 200329 | Adults with clinically suspected sinusitis (purulent nasal discharge and maxillary pain) of 2 to 28 days’ duration, median 4 days’ duration | Primary care clinic | 251 | Median 34 | Latent class model incorporating CRP, radiographs (air-fluid levels or opacity), and clinical findings | Switzerland | NR |

| Varonen, 200328 | Consecutive adults with clinically suspected acute sinusitis <30 days’ duration, 72% more than 5 days | Primary care clinic | 148 | Mean 39.7, range 18 to 75 | Sinus radiographs (AP and Waters’ view) showing total opacification, air-fluid level, or mucosal thickening ≥6 mm | Finland | 1998 to 1999 |

| Berger, 201125 | Consecutive adults with clinically suspected acute bacterial rhinosinusitis between 5 days’ and 4 weeks’ duration | ENT clinic | 104 | Mean 44 | Abnormal sinus radiograph (AP and Waters’ view with air-fluid level, complete opacification, or ≥6 mm mucosal thickening) | Israel | 2003 to 2006 |

| Lewander, 201231 | Adults referred for CT for clinically suspected sinus disease | Radiology clinic | 40 | 57 for men, 54 for women, range 22 to 84 | CT scan showing any opacification or obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex | Sweden | 2008 to 2009 |

| Adults and children | |||||||

| McNeill, 196333 | Adults and children referred for clinically suspected sinusitis | ENT clinic | 150 (242 sinuses) | Inclusion range 10 and older. Age 10–19 (n= 22), 20–29 (n= 35), 30–39 (39), 40–49 (n= 31), 50 and older (n= 23) |

For radiography: AP showing mucopus, or pus. For clinical signs: radiography showing mucosal thickening or any opacity | Northern Ireland | NR |

| Watt-Boolsen, 197734 | Adults and children with clinically suspected maxillary sinusitis | ENT clinic | 286 (468 sinuses) | Range 3 to 93 | AP with return of cloudy fluid | Denmark | NR |

| Berg, 198532 | Adults and children with clinically suspected sinusitis | ENT clinic | 90 | Mean 37, range 10 to 75 | AP showing purulent fluid | Sweden | NR |

| Shapiro, 198637 | Consecutive adults and children with clinically suspected acute sinusitis | Allergy and paediatric clinics | 75 | Median age 10, range 2 to 72 | Radiograph showing at least 3 mm mucosal thickening, clouding, opacification, or air-fluid level | US | NR |

| Gianoli, 199235 | Adults and children undergoing CT for evaluation of clinically suspected sinusitis | Radiology clinic | 41 | Mean 40, range 5 to 80 | CT scan abnormal (> 4 mm mucosal thickening or opacification, excluding solitary polyps) | US | NR |

| Ghatasheh, 200038 | Adults and children with suspected acute maxillary sinusitis referred from emergency department, primary care, or ENT clinics for sinus radiography | Radiology clinic | 50 (100 sinuses) | Mean 23.4, range 6 to 50 | Sinus radiograph (Waters‘ view only) showing mucosal thickening, air-fluid levels, or complete opacification | Jordan | NR |

| Awaida, 200436 | Adults and children referred for sinus CT scan | Radiology clinic | 51 | Mean 40.7, range 11 to 70 | CT scan abnormal | US | 1999 to 2000 |

| Huang, 200839 | Consecutive adults and children with clinically suspected acute sinusitis less than 3 weeks’ duration | Allergy clinic | 217 | Range 4 to 61. Age 4 to 9 (n= 89), age 10 to 19 (n= 101), age 20 and older (n= 27) | Sinus radiograph (n= 151), or CT scan (n= 12) with >4 mm mucosal thickening, air-fluid levels, and/or increased opacity or retention cyst | US | NR |

| Children | |||||||

| Reilly, 198943 | Children with clinically suspected acute sinusitis | ENT clinic | 53 (106 sinuses) | Median age 6, age range 2 to 16 | Radiograph showing opacification or mucosal thickening >4 mm | US | 1985 |

| van Buchem, 199240 | Consecutive children presenting with runny nose | Primary care clinic | 46 (93 sinuses) | Range 2 to 12 | AP showing purulent fluid or positive bacterial culture | Netherlands | 1984 to 1985 |

| Visca, 199541 | Children with clinically suspected sinusitis | Respiratory clinic at paediatric hospital | 30 | Range 5 to 15 | CT scan abnormal in coronal projection | Italy | NR |

| Fufezan, 201042 | Children with clinically suspected sinusitis, including poorly controlled asthma | Paediatric clinic | 67 | Range 4 to 16 | Sinus radiographs with total opacity of the maxillary sinus, air-fluid level, or mucosal thickening | Romania | NR |

| Not reported | |||||||

| Goodman, 199544 | Convenience sample of patients with clinically suspected sinusitis | Sinus referral clinic | 44 | NR | CT scan showing incomplete aeration, air-fluid level, or mucosal thickening | US | NR |

| Dobson, 199645 | Patients with clinically suspected maxillary sinusitis | ENT clinic | 25 (50 sinuses) | NR | Sinus radiographs showing mucosal thickening, air-fluid level, or complete opacification | UK | NR |

Two other publications by Hansen are excluded as they used the same group of patients.

Reported results for both MRI and radiography as reference standard for ultrasound. Only MRI results are used.

AP = antral puncture. CRP = C-reactive protein. CT = computed tomography. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. NR = not reported.

Appendix 5. The risk of bias in QUADAS-2 study design domains.

Appendix 6. Prevalence of acute sinusitis in the included studies, by population, inclusion criteria, and reference standarda

| Study | Reference standard | Sinusitis/total | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults, or adults and children with clinically suspected sinusitis | |||

|

| |||

| Berg, 1981 | AP | 25/50 | 50.0 |

| Berg, 1985 | AP | 43/90 | 47.8 |

| Bergstedt, 1980 | AP | 23/48 | 47.9 |

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 92/174 | 52.9 |

| Kuusela, 1983 | AP | 82/156 | 52.6 |

| Laine, 1998 | AP | 23/72 | 31.9 |

| McNeill, 1963 | AP | 100/242 | 41.3 |

| Savolainen, 1997a | AP | 165/234 | 70.5 |

| Savolainen, 1997b | AP | 187/234 | 79.9 |

| van Buchem, 1995 | AP | 71/203 | 35.0 |

| Watt-Boolsen, 1997 | AP | 221/468 | 47.2 |

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal: | 49 (42 to 57) | ||

| Gianoli, 1992 | CT | 11/67 | 16.4 |

| Goodman, 1995 | CT | 60/88 | 68.2 |

| Lewander, 2012 | CT | 14/80 | 17.5 |

| Awaida, 2004 | CT | 32/51 | 62.7 |

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 127/201 | 63.2 |

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal: | 44 (23 to 67) | ||

| Berger, 2011 | Rad | 52/104 | 50.0 |

| Shapiro, 1986 | Rad | 63/150 | 42.0 |

| Jensen, 1987 | Rad | 120/253 | 47.4 |

| Rohr, 1986 | Rad | 91/198 | 46.0 |

| Dobson, 1996 | Rad | 28/50 | 56.0 |

| Ghatasheh, 2000 | Rad | 54/100 | 54.0 |

| Huang, 2008 | Rad | 151/217 | 69.6 |

| Varonen, 2003 | Rad | 13/32 | 40.6 |

| Young, 2003 | Rad | 67/241 | 27.8 |

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal: | 48 (39 to 57) | ||

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal, any reference standard: | 48 (42 to 54) | ||

|

| |||

| Children with clinically suspected sinusitis | |||

|

| |||

| Visca, 1995 | CT | 17/30 | 56.7 |

| Fufezan, 2010 | Rad | 71/134 | 53.0 |

| Reilly, 1989 | Rad | 18/96 | 18.8 |

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal: | 41 (19 to 67) | ||

|

| |||

| Patients with acute respiratory tract infection | |||

|

| |||

| van Buchem, 1992 (children) | AP | 17/107 | 15.9 |

| Puhakka, 2000 (adults) | MRI | 94/394 | 23.9 |

|

| |||

| Pooled subtotal: | 20 (14 to 29) | ||

|

| |||

| Overall total | 46 (40 to 53) | ||

Subtotals pooled using a random effects model. If a study reports different numbers of patients with different signs and symptoms, the data for the greatest number of patients reported were used.

AP = antral puncture revealing purulence. CT = computed tomography. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. Rad = radiography.

Appendix 7. Accuracy of imaging studies for diagnosis of acute sinusitis

| Study | Ref std | Pop’n | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiography | ||||||||||||

| Antral puncture as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| Berg, 1981 | AP | A | 25 | 17 | 0 | 8 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.47 | 0.00 | ||

| Bergstedt, 1980 | AP | A | 23 | 18 | 0 | 7 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 1.39 | 0.00 | ||

| Laine, 1998 | AP | A | 14 | 1 | 9 | 48 | 0.61 | 0.98 | 29.83 | 0.40 | ||

| Savolainen, 1997b | AP | A | 174 | 18 | 13 | 29 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 2.43 | 0.11 | ||

| van Buchem, 1995 | AP | A | 53 | 39 | 14 | 81 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 2.43 | 0.31 | ||

| McNeill, 1963 | AP | B | 82 | 54 | 18 | 88 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 2.16 | 0.29 | ||

| Watt-Boolsen, 1977 | AP | B | 194 | 161 | 27 | 86 | 0.88 | 0.35 | 1.35 | 0.35 | ||

| Kuusela, 1983 | AP | A | 68 | 21 | 14 | 53 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 2.96 | 0.24 | ||

| van Buchem, 1992 | AP | C | 12 | 59 | 5 | 31 | 0.71 | 0.34 | 1.08 | 0.85 | ||

| Summary | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.90) | 0.56 (0.38 to 0.73) | 2.01 (1.40 to 3.05) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.39) | 0.820 | |||||||

| Imaging as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| Young, 2003 | LC | A | 54 | 36 | 13 | 137 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 3.87 | 0.25 | ||

| Puhakka, 2000 | MRI | A | 16 | 0 | 6 | 58 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 73.00 | 0.27 | ||

| Visca, 1995 | CT | C | 16 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 1.75 | 0.13 | ||

| Summary | 0.80 (0.66 to 0.89) | 0.84 (0.31 to 0.98) | 9.37 (1.27 to 39.6) | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.48) | 0.841 | |||||||

| Summary (all) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.89) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.78) | 2.36 (1.57 to 3.68) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.34) | 0.836 | |||||||

| Ultrasound | Mode | |||||||||||

| A mode, AP as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| Laine, 1998 | AP | A (Sinuscan 101) | A | 14 | 23 | 9 | 26 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 1.30 | 0.74 | |

| Savolainen, 1997b | AP | A (Sinuscan 102) | A | 180 | 33 | 7 | 14 | 0.96 | 0.30 | 1.37 | 0.13 | |

| Kuusela, 1983 | AP | A (Sinuscan 101) | A | 58 | 27 | 24 | 47 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 1.97 | 0.45 | |

| Berg, 1985 | AP | A (Sinuson 810) | B | 27 | 14 | 16 | 33 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 2.11 | 0.53 | |

| Summary | 0.79 (0.52 to 0.93) | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.71) | 1.71 (1.42 to 2.08) | 0.41 (0.19 to 0.68) | 0.679 | |||||||

| B mode, AP as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| van Buchem, 1992a | AP | B (3.5 Mhz sector scanner Philips SP 3000) | C | 2 | 25 | 13 | 63 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 1.21 | |

| van Buchem, 1995 | AP | B (5 Mhz sectorscan) | A | 51 | 33 | 7 | 68 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 2.69 | 0.18 | |

| Summary | 0.53 (0.03 to 0.98) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.77) | 1.64 (0.10 to 3.2) | 0.69 (0.03 to 1.36) | 0.693 | |||||||

| A mode, imaging as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| Varonen, 2003 | Rad | A (Sinuscan 102) | A | 12 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 17.5 | 0.08 | |

| Puhakka, 2000 | MRI | A (Sinuscan 102) | A | 14 | 3 | 8 | 55 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 12.3 | 0.38 | |

| Shapiro, 1986 | Rad | A (Echosine) | B | 33 | 34 | 30 | 53 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 1.34 | 0.78 | |

| Jensen, 1987 | Rad | A (Sinuson 810) | A | 77 | 15 | 43 | 118 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 5.69 | 0.40 | |

| Reilly, 1989 | Rad | A (Sinus V) | C | 10 | 2 | 8 | 86 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 24.4 | 0.45 | |

| Rohr, 1986 | Rad | A (Echosine) | A | 26 | 4 | 17 | 45 | 0.60 | 0.92 | 7.41 | 0.43 | |

| Summary | 0.62 (0.55 to 0.69) | 0.91 (0.79 to 0.96) | 7.64 (2.95 to 17.1) | 0.42 (0.32 to 0.54) | 0.702 | |||||||

| B mode, imaging as reference standard | ||||||||||||

| Ghatasheh, 2000 | Rad | B (not stated) | B | 42 | 0 | 12 | 46 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 78.00 | 0.22 | |

| Fufezan, 2010 | Rad | B (Sonoace 8000 EX) | C | 50 | 1 | 21 | 62 | 0.70 | 0.98 | 44.37 | 0.30 | |

| Dobson, 1996 | Rad | B (Acuson 128) | NR | 22 | 0 | 6 | 22 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 79.00 | 0.21 | |

| Gianoli, 1992 | CT | B (5 Mhz sectorscan) | B | 11 | 1 | 0 | 55 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 56.00 | 0.00 | |

| Summary | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.81) | 0.98 (0.94 to 0.99) | 38.4 (12.7 to 88.3) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.34) | 0.897 | |||||||

| Summary (AP) | AP | 0.73 (0.49 to 0.88) | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.69) | 1.72 (1.32 to 2.12) | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.81) | 0.659 | ||||||

| Summary (imaging) | Imaging | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.73) | 0.94 (0.88 to 0.97) | 12.4 (5.1 to 26.0) | 0.35 (0.28 to 0.43) | 0.796 | ||||||

| Summary (all) | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.79) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.91) | 4.40 (2.46 to 7.48) | 0.35 (0.25 to 0.48) | 0.820 | |||||||

| Screening CT | ||||||||||||

| Goodman, 1995 | CT | NR | 56 | 3 | 4 | 25 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 8.71 | 0.07 | ||

| Awaida, 2004 | CT | B | 26 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 7.36 | 0.21 | ||

| Summary (all) | 0.88 (0.71 to 0.96) | 0.89 (0.77 to 0.95) | 9.01 (3.77 to 18.3) | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.33) | 0.895 |

Excluding this study as an outlier due to its very low sensitivity, the results for the remaining studies using antral puncture as the reference standard are: sensitivity 0.80 (95% CI = 0.60 to 0.92), specificity 0.58 (95% CI = 0.43 to 0.71), positive likelihood ratio 1.89 (95% CI = 1.48 to 2.45), and negative likelihood ratio 0.35 (95% CI = 0.16 to 0.60).

A = patient population of adults. AP = antral puncture showing purulent fluid. AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. B = patient population of both adults and children. C = patient population of children. CT = computed tomography. FN = false negative. FP = false positive. LC = latent class analysis. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. NR = not reported. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. Pop’n = population. Rad = radiography. Ref std = reference standard. TN = true negative. TP = true positive

Appendix 8. Accuracy of blood tests for the diagnosis of acute sinusitis in adultsa

| Study | Ref std | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | DOR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP >10 mg/L | |||||||||||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 67 | 32 | 25 | 49 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 1.84 | 0.45 | 4.09 | |

| CRP>20–25 mg/L | |||||||||||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 48 | 18 | 44 | 63 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 2.35 | 0.61 | ||

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 28 | 6 | 98 | 67 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 2.70 | 0.85 | ||

| Savolainen, 1997a | BC | 51 | 4 | 86 | 35 | 0.37 | 0.90 | 3.63 | 0.70 | ||

| Young, 2003 | Rad | 32 | 28 | 35 | 146 | 0.48 | 0.84 | 2.97 | 0.62 | ||

| Summary | 0.39 (0.29 to 0.50) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.91) | 2.92 (2.17 to 3.98) | 0.71 (0.60 to 0.80) | 4.11 | ||||||

| CRP>40–49 mg/L | |||||||||||

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 12 | 2 | 114 | 71 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 3.48 | 0.93 | ||

| Savolainen, 1997a | BC | 27 | 3 | 110 | 36 | 0.20 | 0.92 | 2.56 | 0.87 | ||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 30 | 8 | 62 | 73 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 3.30 | 0.75 | ||

| Summary | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.30) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.95) | 2.46 (1.45 to 3.91) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.93) | 2.86 | 0.721 | |||||

| ESR >10 | |||||||||||

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 89 | 32 | 37 | 41 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 1.61 | 0.52 | ||

| Savolainen, 1997a | BC | 91 | 16 | 46 | 23 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 1.62 | 0.57 | ||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 21 | 2 | 11 | 17 | 0.66 | 0.89 | 6.23 | 0.38 | ||

| Summary | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.72) | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.65) | 1.60 (1.33 to 1.97) | 0.57 (0.46 to 0.68) | 2.81 | ||||||

| ESR >20 | |||||||||||

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 40 | 8 | 86 | 65 | 0.32 | 0.89 | 2.90 | 0.77 | ||

| van Buchem, 1995 | AP | 14 | 6 | 39 | 50 | 0.26 | 0.89 | 2.47 | 0.82 | ||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 29 | 14 | 28 | 46 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 2.18 | 0.64 | ||

| Summary | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.51) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.92) | 2.55 (1.68 to 3.74) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.85) | 3.45 | ||||||

| ESR >30 | |||||||||||

| Hansen, 1995 | AP | 23 | 5 | 66 | 74 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 4.08 | 0.79 | 5.16 | |

| ESR >40 | |||||||||||

| Savolainen, 1997a | BC | 26 | 1 | 111 | 38 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 7.40 | 0.83 | 8.91 | 0.684 |

| WBC>10 | |||||||||||

| Lindbaek, 1996 | CT | 31 | 8 | 95 | 65 | 0.25 | 0.89 | 2.25 | 0.85 | ||

| Savolainen, 1997a | BC | 35 | 5 | 102 | 34 | 0.26 | 0.87 | 1.99 | 0.85 | ||

| Summary | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.31) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.93) | 2.23 (1.29 to 3.66) | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.94) | 2.62 | 0.710 |

No studies with children were identified. Where results for more than one study are presented, a summary estimate is shown.

AP = antral puncture revealing purulent fluid. AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. BC = bacterial culture of antral fluid positive for pathogenic bacteria. CRP = C-reactive protein. CT = computed tomography. DOR = diagnostic odds ratio (positive likelihood ratio divided by negative likelihood ratio). ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate. FN = false negative. FP = false positive. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. Rad = radiography. Ref std = reference standard. TN = true negative. TP = true positive. WBC = white blood cells.

Appendix 9. Accuracy of miscellaneous tests for the diagnosis of acute sinusitis

| Test | Study | Ref std | Pop’n | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sens | Spec | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical nasal secretion score ≥4 | Huang, 2008 | Rad | B | 144 | 0 | 7 | 66 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 95.00 | 0.05 |

| Leucocyte esterase ≥1+ in nasal secretions | Huang, 2008 | Rad | B | 126 | 3 | 25 | 63 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 18.36 | 0.17 |

| Nitrite >1.0 in nasal secretions | Huang, 2008 | Rad | B | 78 | 4 | 73 | 55 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 7.62 | 0.52 |

| pH >7 in nasal secretions | Huang, 2008 | Rad | B | 145 | 38 | 6 | 28 | 0.96 | 0.42 | 1.67 | 0.09 |

| Protein >2.0 in nasal secretions | Huang, 2008 | Rad | B | 145 | 14 | 6 | 52 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 4.53 | 0.05 |

| Leucocytes in sinus washings | van Buchem, 1995 | AP | A | 56 | 27 | 11 | 93 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 3.71 | 0.21 |

| Leucocytes in sinus washings | van Buchem, 1992 | AP | C | 4 | 5 | 9 | 75 | 0.31 | 0.94 | 4.92 | 0.74 |

| Leucocytes in nasal secretions | Visca, 1995 | CT | C | 16 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 3.06 | 0.08 |

| Flexible endoscopy | Berger, 2011 | Rad | A | 43 | 17 | 9 | 35 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 2.53 | 0.26 |

| Rhinoscopy — pus in nasal cavity | Young, 2003 | Rad | A | 55 | 108 | 12 | 66 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 1.32 | 0.47 |

| Rhinoscopy — pus in throat | Young, 2003 | Rad | A | 17 | 33 | 51 | 141 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 1.32 | 0.93 |

| Scintigraphy (probably or definitely abnl) | Bergstedt, 1980 | AP | A | 21 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 11.41 | 0.09 |

| Diode gas laser spectroscopy (frontal sinus) | Lewander, 2012 | CT | A | 12 | 4 | 2 | 62 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 14.14 | 0.15 |

| Diode gas laser spectroscopy (maxillary sinus) | Lewander, 2012 | CT | A | 7 | 4 | 11 | 53 | 0.39 | 0.93 | 5.54 | 0.66 |

A = patient population of adults. Abnl = abnormal. AP = antral puncture showing purulent fluid. B = patient population of both adults and children. C = patient population of children. CT = computed tomography. FN = false negative. FP = false positive. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. Pop’n = population. Rad = radiography. Ref std = reference standard. Sens = sensitivity. Spec = specificity. TP = true positive. TN = true negative.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics Ambulatory Health Care Data. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/web_tables.htm (accessed 25 Jul 2016)

- 2.Williams JW, Simel DL. Does this patient have sinusitis? Diagnosing acute sinusitis by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1993;270(10):1242–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 Suppl):S1–S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006089. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006089.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerrum L, Gahm-Hansen B, Munck AP. C-reactive protein measurement in general practice may lead to lower antibiotic prescribing for sinusitis. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(506):659–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2078–2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 Suppl):S1–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson PJ, Brereton JM, Roberson DW, et al. Choosing Wisely: our list. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(4):534–536. doi: 10.1177/0194599813479577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):798–808. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. Technical report: evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated sinusitis in children: a systematic overview. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):e57. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MJ. Evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated sinusitis in children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e284–e296. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varonen H, Makela M, Savolainen S, et al. Comparison of ultrasound, radiography, and clinical examination in the diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(9):940–948. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Dendukuri N. Statistics for quantifying heterogeneity in univariate and bivariate meta-analyses of binary data: the case of meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Stat Med. 2014;33(16):2701–2717. doi: 10.1002/sim.6115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg O, Bergstedt H, Carenfelt C, et al. Discrimination of purulent from nonpurulent maxillary sinusitis. Clinical and radiographic diagnosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90(3 Pt 1):272–275. doi: 10.1177/000348948109000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergstedt HF, Carenfelt C, Lind MG. Facial bone scintigraphy. VI. Practical clinical use in inflammatory disorders of the maxillary sinus. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1980;21(5):651–656. doi: 10.1177/028418518002100513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuusela T, Kurri J, Sirola R. Ultraschall in der Sinusitis-Diagnostik bei Rekruten — Vergleich der Befunde der Punktion, Ultraschall— und Röntgenuntersuchung. [Ultrasound in sinusitis diagnosis among recruits — Comparison of the results of the puncture, ultrasound and X-ray examination] Wehrmed Mschr Heft. 1983;11:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen JG, Schmidt H, Rosborg J, Lund E. Predicting acute maxillary sinusitis in a general practice population. BMJ. 1995;311(6999):233–236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laine K, Maatta T, Varonen H, Makela M. Diagnosing acute maxillary sinusitis in primary care: a comparison of ultrasound, clinical examination and radiography. Rhinology. 1998;36(1):2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savolainen S, Jousimies-Somer H, Karjalainen J, Ylikoski J. Do simple laboratory tests help in etiologic diagnosis in acute maxillary sinusitis? Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1997a;529:144–147. doi: 10.3109/00016489709124107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savolainen S, Pietola M, Kiukaanniemi H, et al. An ultrasound device in the diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh) 1997b;529:148–152. doi: 10.3109/00016489709124108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Buchem L, Peeters M, Beaumont J, Knottnerus JA. Acute maxillary sinusitis in general practice: the relation between clinical picture and objective findings. Eur J Gen Pract. 1995;1(4):155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindbaek M, Hjortdahl P, Johnsen UL. Use of symptoms, signs, and blood tests to diagnose acute sinus infections in primary care: comparison with computed tomography. Fam Med. 1996;28(3):183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger G, Berger RL. The contribution of flexible endoscopy for diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(2):235–240. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen C, von Sydow C. Radiography and ultrasonography in paranasal sinusitis. Acta Radiol. 1987;28(1):31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohr AS, Spector SL, Siegel SC, et al. Correlation between A-mode ultrasound and radiography in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78(1 Pt 1):58–61. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varonen H, Savolainen S, Kunnamo I, et al. Acute rhinosinusitis in primary care: a comparison of symptoms, signs, ultrasound, and radiography. Rhinology. 2003;41(1):37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young J, Bucher H, Tschudi P, et al. The clinical diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in general practice and its therapeutic consequences. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(4):377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puhakka T, Heikkinen T, Makela MJ, et al. Validity of ultrasonography in diagnosis of acute maxillary sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(12):1482–1486. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.12.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewander M, Lindberg S, Sevensson T, et al. Non-invasive diagnostics of the maxillary and frontal sinuses based on diode laser gas spectroscopy. Rhinology. 2012;50(1):26–32. doi: 10.4193/Rhino10.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg O, Carenfelt C. Etiological diagnosis in sinusitis: ultrasonography as clinical complement. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(7 Pt 1):851–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNeill RA. Comparison of the findings on transillumination, X-ray and lavage of the maxillary sinus. J Laryngol Otol. 1963;77:1009–1013. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100061673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watt-Boolsen S, Karle A. The clinical use of radiological examination of the maxillary sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1977;2(1):41–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1977.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gianoli GJ, Mann WJ, Miller RH. B-mode ultrasonography of the paranasal sinuses compared with CT findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107(6 Pt 1):713–720. doi: 10.1177/019459988910700601.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awaida JP, Woods SE, Doerzbacher M, et al. Four-cut sinus computed tomographic scanning in screening for sinus disease. South Med J. 2004;97(1):18–20. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000087192.54366.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro GG, Furukawa CT, Pierson WE, et al. Blinded comparison of maxillary sinus radiography and ultrasound for diagnosis of sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;77(1 Pt 1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghatasheh M, Smadi A. Ultrasonography versus radiography in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6(5–6):1083–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang SW, Small PA. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial sinusitis in patients using a simple test of nasal secretions. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29(6):640–643. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Buchem FL, Peeters MF, Knottnerus JA. Maxillary sinusitis in children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1992;17(1):49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1992.tb00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visca A, Castello M, DeFilippi C. Considerazioni diagnostiche sulla sinusite in eta pediatrica. [Diagnostic considerations on sinusitis in childhood] Minerva Pediatr. 1995;47(5):171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fufezan O, Asavoaie C, Chereches Panta P, et al. The role of ultrasonography in the evaluation of maxillary sinusitis in pediatrics. Med Ultrason. 2010;12(1):4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reilly JS, Hotaling AJ, Chiponis D, Wald ER. Use of ultrasound in detection of sinus disease in children. Int J Pedatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1989;17(3):225–230. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(89)90049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodman GM, Martin DS, Klein J, et al. Comparison of a screening coronal CT versus a contiguous coronal CT for the evaluation of patients with presumptive sinusitis. Ann Allerg Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dobson MJ, Fields J, Woodford T. A comparison of ultrasound and plain radiography in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis. Clin Radiol. 1996;51(3):170–172. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Little P, Stuart B, Francis N, et al. for the GRACE consortium Effects of internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, randomised, factorial, controlled trial. Lancet 2013. 382(9899):1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cals JW, Schot MJ, de Jong SA, et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):124–133. doi: 10.1370/afm.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bornemann P, Bornemann G. Military family physicians’ perceptions of a pocket point-of-care ultrasound device in clinical practice. Mil Med 2014. 179(12):1474–1477. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levin DC, Rao VM, Parker L, Frangos AJ. Noncardiac point-of-care ultrasound by nonradiologist physicians: how widespread is it? J Am Coll Radiol 2011. 8(11):772–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]