Abstract

Background

With increasing numbers of people living with complex life-limiting multimorbidity in the community, consideration must be given to improving the organisation and delivery of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care (EOLC).

Aim

To provide insight into the experience of GPs providing EOLC in the community, particularly the facilitators and barriers to good-quality care.

Design and setting

A web-based national UK questionnaire survey circulated via the Royal College of General Practitioners, NHS, Marie Curie, and Macmillan networks to GPs.

Method

Responses were analysed using descriptive statistics and an inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Responses were received from 516 GPs, who were widely distributed in terms of practice location. Of these, 97% felt that general practice plays a key role in the delivery of care to people approaching the end of life and their families. Four interdependent themes emerged from the data: continuity of care — which can be difficult to achieve because of resource concerns including time, staff numbers, increasing primary care workload, and lack of funding; patient and family factors — with challenges including early identification of palliative care needs and recognition of the end of life, opportunity for care planning discussions, and provision of support for families; medical management — including effective symptom-control and access to specialist palliative care services; and expertise and training — the need for training and professional development was recognised to enhance knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards EOLC.

Conclusion

The findings reveal enduring priorities for policy, commissioning, practice development, and research in future primary palliative care.

Keywords: end-of-life care, palliative care, primary care, qualitative research, survey

INTRODUCTION

Improving care for patients who are dying (end-of-life care, EOLC) is an enduring clinical priority. For many years there have been concerns about deficits in current practice.1,2 In the UK, more people are living longer with multiple long-term conditions and cancer such that illness trajectories are changing.3–5 A proactive approach to care, with early identification of palliative care needs and care planning, has long been advocated,4,5 and remains at the centre of national strategies in the UK.6–9

GPs, along with the wider palliative care and community nursing teams, provide most of the medical care for patients who die in the community at end of life.10–13 Previous research suggests that GPs highly value this part of their work.10,14 Patients benefit if the GP is accessible, provides continuity of care, takes time to listen, and addresses symptom-control concerns.10 GP home visits have been identified as a necessary component of good EOLC at home.15 With primary care in the UK now under ‘unprecedented pressure’,16 however, the way in which high-quality EOLC in the community is achieved requires urgent consideration. This is particularly relevant as ‘new models’ of primary care emerge, such as GP super-practices and federations.17 In this context, this questionnaire survey was designed to capture an up-to-date insight into the experiences of GPs providing EOLC in the community. This study reports analysis of quantitative data and free-text answers to a subset of questions relevant to the following research questions:

What is the current experience of GPs delivering EOLC?

What barriers and facilitators do they identify to the provision of EOLC?

METHOD

Questionnaire

The online questionnaire survey was developed as part of the clinical priority workstream of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Clinical Innovation and Research Centre (CIRC). The questions were informed by previous research and peer-reviewed by an expert advisory group for relevance and comprehensibility. The questionnaire survey comprised a total of 26 questions: closed questions including responder demographics, job role, and questions inviting free-text responses relating to experiences and perceptions of the provision of EOLC. The study reported here focused on a subset of questions, as listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Subset of survey questions for qualitative data analysis.

|

|

|

Population and setting

The questionnaire survey aimed to describe the views of GPs nationally, and was circulated electronically via regular RCGP communications and cascaded through RCGP, NHS, Marie Curie, and Macmillan networks to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and GP practices. The survey was conducted between May and August 2015.

How this fits in

This questionnaire survey provides insight into current experiences of delivering end-of-life care (EOLC) by GPs. The findings suggest that GPs perceive limited progress in terms of enhancing the quality of EOLC that is delivered in primary care. This must be considered in terms of the increasing number of patients who require EOLC, and a pressured and changing primary care environment in the UK. Service delivery concerns in EOLC should remain a priority area for policymakers and researchers.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. The free-text comments associated with the questions outlined in Box 1 were analysed using an inductive, iterative thematic approach.18,19 All qualitative data were anonymised, and the data were coded independently by two researchers. Initial codes were collated, mapped out, and compared with extrapolate overarching and crosscutting themes. All the free-text data were coded using NVivo 10 software (version 10).

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 516 responses were received from GPs. Of these, 227 gave details of the area in which they work (43.9%). Responses were received from GPs who work in 112 (53.6%) of the 209 CCG areas in England. In addition, responses were received from GPs in Scotland and Wales.

Of the responses, 431 (83.5%) included free-text responses to the questions mentioned above, a total of 15 510 words (average 35 words a response). In addition to general practice, the participants worked in a wide range of settings including care homes, hospices, care homes for people with learning disabilities, out-of-hours services, genitourinary medicine clinics, prisons, and geriatric services. Professional roles included commissioning, teaching, facilitator and academic roles, as well as clinical practice. Professional roles included GP with a Special Interest (GPwSI) in EOLC, commissioning, teaching and academic roles, as well as clinical practice (further details provided in Tables 1 and 2). Of the responders, 500 (97%) felt that general practice plays a key role in the delivery of care to people approaching the end of their life and their families. The frequency with which GPs cared for patients at the end of life varied (Table 3), and is likely to have been affected by location of work, which for some included hospices and nursing homes.

Table 1.

Job roles of GPs

| Job role | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| GP trainee | 28 | 5.4 |

| GPwSI in EOLC | 2 | 0.4 |

| Locum | 21 | 4.1 |

| Partner | 369 | 71.5 |

| Salaried | 96 | 18.6 |

| Total responders | 516 | 100.0 |

EOLC = end-of-life care. GPwSI = GP with a special interest.

Table 2.

Number of years GPs spent in general practice

| Years in general practice | n | %a |

|---|---|---|

| <5 | 79 | 15.4 |

| 5–10 | 79 | 15.4 |

| >10 | 354 | 69.1 |

| Not stated | 4 | 0.8 |

| Total responders | 516 | 100.0 |

Percentages were rounded to the nearest 0.1%.

Table 3.

Frequency of GP involvement in end-of-life care

| Frequency | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Daily | 45 | 8.7 |

| Weekly | 234 | 45.3 |

| Monthly | 171 | 33.1 |

| Occasionally | 62 | 12.0 |

| Not stated | 4 | 0.8 |

| Total | 516 | 100.0% |

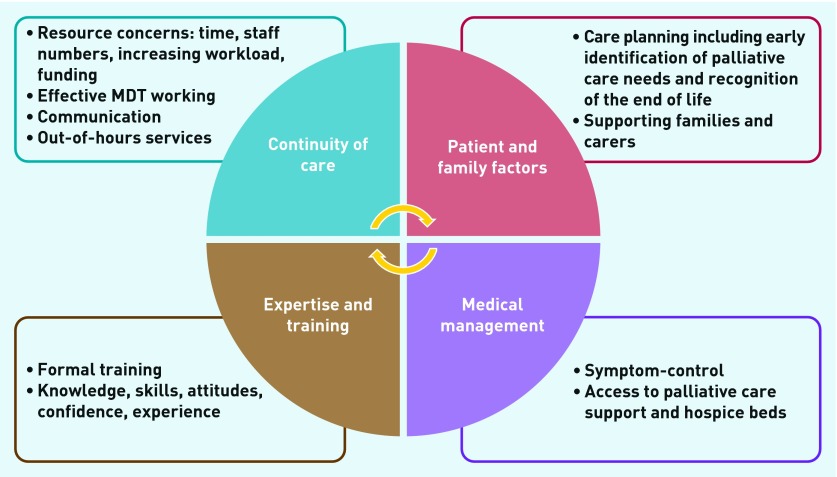

Four overarching themes emerged from the data in relation to current experiences of the delivery of EOLC: continuity of care; patient and family factors; medical management; and expertise and training. The themes overlapped, and are presented below using a selection of representative example quotes. Responders more often described barriers to the provision of EOLC, with facilitators to the delivery of good-quality care offered less often (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of main themes from qualitative data analysis. MDT = multidisciplinary team.

Continuity of care

Continuity of care was identified as being of vital importance in the provision of EOLC in primary care. Only 122 out of 492 (24.8%) responders stated that they always had the chance to discuss EOLC wishes with patients. Several organisational issues influenced the extent to which this occurred, as described below.

Resource concerns

Lack of resources inhibited continuity of care, particularly in relation to time, staff numbers, increasing workload, and funding. A dominant theme was the importance of time with patients, something which is threatened by their current workload:

‘Time to spend with patients which we do not have and time to spend with patients which has been eroded by increasing workload in all areas. 10 minutes in surgery and a little more on a home visit to make life enhancing decisions and arrangements is insufficient even if we are “EOL experts”.’

(#453, GP Partner, >10 years, Chorley and South Ribble CCG)

‘… unfunded transfer of complex palliative care into community, unethical drive to increase numbers of patients dying at home with the totally irresponsible and unethical promise of hospice level care in the community.’

(#472, GP Partner, >10 years, Salford CCG)

Multidisciplinary team working

Effective multidisciplinary team (MDT) working, including with district nurses (DNs) and specialist palliative care teams, was identified as important in delivering effective EOLC. Difficulties in achieving this were highlighted:

‘Main barriers are the sad lack of district nursing staff which is very under-resourced in our area. District nurses that are confident and well trained in generalist palliative care make things move smoother and prevent the need for crisis management.’

(#420, GP Partner, >10 years, Stockport CCG)

Effective MDT working, when achieved, was seen as facilitating the provision of EOLC but was under threat because of other organisational and funding challenges:

‘We have an excellent local team of district nurses who are very confident in and willing to manage terminal care at home. There is a significant threat to this in proposed centralisation of DN services, which would mean that we would work with whatever DN was available rather than the one that we know and trust from our team.’

(#102, GP Partner, 5–10 years, area not known)

Communication

Among the community MDT, the opportunity for regular communication was considered essential, and a need for more effective communication systems was described:

‘Services are too fragmented. GP, OOH, ambulance, social care, district nurses, OOH district nurses, voluntary hospice at home.’

(#292, GP Partner, 5–10 years, Corby CCG)

‘Communication with district nurses is not always easy. Usually by message book and answer phone rather than direct conversation.’

(#266, GP Partner, >10 years, South Cheshire CCG)

Out-of-hours services

Out-of-hours (OOH) services were mentioned often in relation to their potential to disrupt or enable continuity of care. Lack of ability to share electronic patient records with OOH services was recognised as contributing to an inability for OOH staff to be able to react according to patients’ wishes. Interaction with the 111 national helpline service was also described as potentially problematic:

‘There needs to be better communication between OOH care and the day GP. I work in both and am aware of the difficulties. I don’t believe the [electronic] record is user-friendly or very helpful. Having some sort of plan in the patient’s home from the GP can be very useful.’

(#239, GP Partner, 5–10 years, Kingston)

‘… always out of hours — lack of support for families/lack of their involvement in planning; unexpected symptoms leading OOH GP to advise A&E [accident and emergency]; lack of palliative care cover/prompt assessments within 24 hours, patchy OOH primary care quality and adverse effects of 111 triaging.’

(#397, GP Partner, >10 years, Bexley)

Responders described ways of working around these challenges, for example, by ensuring the provision of handover documents to OOH services. A small number of responders described providing their own telephone numbers to patients and families.

Patient and family factors

Key factors concerning patients and families included opportunity for care planning discussions, and the provision of nursing care and practical support for family carers.

Care planning

GPs had concerns not only about lack of time to have sensitive care planning discussions, but also about the timing of those conversations, particularly for those with non-malignant disease. This was felt to lead to a lack of responsiveness to patients’ wishes, as well as avoidable pressure on the emergency care system, particularly in the context of lack of integration with OOH care:

‘Frequently those chronic life-limiting illnesses where it can be difficult to judge when appropriate to start the care planning. Many GPs too afraid to start this so patient don’t get their fears addressed and call ambulances. Yet another example of the extra pressure on GPs causing harm to patients.’

(#111, GP Locum, <5 years, CCG unknown)

‘Lack of early enough recognition and lack of advance care planning or lack of communication to out of hours service regarding this. Big barrier is lack of planning. Also lack of continuity of care and lack of time to have important conversations with patients.’

(#11, Salaried GP, <5 years, CCG unknown)

Supporting families/carers

Ensuring that families have the necessary information to cope with an impending crisis can allow measures to be put in place to avert its onset. Responders identified that a lack of practical support, particularly nursing care, can lead to families and carers being unable to cope:

‘Patient’s family members feeling uncomfortable about ongoing care at home and insufficient support available for the family to cope (usually meaning the family would need someone there 24 hours a day to continue at home).’

(#226, Salaried GP, <10 years, South Tyneside CCG)

Some responders outlined cases in which strong support for families and carers was achieved, including sufficient care planning, enabling the effective provision of EOLC:

‘We have had some amazing stories from families who have really appreciated the care their loved ones have received and they have been able to see it all and witness it. This has been planned and delivered with precision & accuracy — not a chance event.’

(#510, GP Partner, >10 years, Tameside & Glossop CCG)

Medical management

Issues relating to adequate symptom-control, access to specialist palliative care services including hospice beds, and access to medication were described.

Symptom-control

Sudden deteriorations in a patient’s condition and inadequate symptom-control were identified as a consequence of avoidable delays in clinical assessment and accessing or administering medication:

‘Formal carers unable to “measure out” liquid pain relief. District nurses and GPs too stretched to be able to get to patient in timely fashion. Night district nurses covering too large an area to get back. Too much paperwork required when doses have to be increased to allow DNs to administer quickly. Chemists unable to supply medication quickly when changes needed.’

(#386, GP Locum, >10 years, Western Cheshire)

Specialist palliative care services and hospice beds

Variability in availability of specialist palliative care services was described by many participants, and linked to being unable to provide adequate support to patients and families. A lack of local hospice beds was described by a number of responders. Of the GPs, 316 out of 483 (65%) stated that they had 24-hour access to specialist palliative care services, and 124 out of 483 (26%) stated that they did not. The remaining 43 out of 483 (9%) stated ‘other’, and examples were given of services that were less than 24 hours a day:

‘Patient deemed not to be complex enough to need hospice bed and so died in hospital.’

(#223, GP Locum, >10 years, Bristol South CCG)

‘Lack of joined up care, difficulty in contacting specialist services.’

(#196, Salaried GP, 5–10 years, unknown CCG)

Conversely, when specialist palliative care services were accessible and perceived to be responsive these were valued:

‘We have a rapid response specialist palliative care team and also 24 hour advice line to enable care 24/7.’

(#048, Partner >10 years, unknown CCG)

Expertise and training

Lack of experience and a lack of training were mentioned very often in relation to GPs and community staff, including staff in care homes. Of the GPs, 19 out of 513 (3.7%) stated that they had had no training in the delivery of EOLC, and 112 out of 513 (21.8%) stated they had received inadequate training. Adequate training was reported by 321 out of 513 (62.6%) responders. The remaining 61 participants (11.9%) answered ‘other’ to this question and provided free-text details, highlighting particularly the need to actively seek out training courses in EOLC.

Ensuring competency and knowledge remains up to date can be challenging when the clinical delivery of EOLC is sporadic. Variability in individual practice, expertise, and confidence were highlighted, with an inability to ensure access training because of rising workloads and pressure on staff and time resources:

‘Care home staff/family/primary care professional lack of confidence/perceived or actual lack of support … Lack of expert knowledge for managing complex/difficult symptoms.’

(#103, Locum, <5 years, unknown CCG)

DISCUSSION

Summary

This questionnaire survey provides a valuable contemporary insight into the experience of GPs delivering EOLC in the community in the UK. Key, interdependent themes revealed through the analysis are summarised in Figure 1. Enduring priorities are practice development, commissioning, and training and research in primary palliative care. GPs and the wider primary care team, notably community nursing teams, require adequate time resource and organisational support to deliver the high-quality palliative and EOLC that they wish to, and which patients and families require. Primary palliative care represents a priority area for those with responsibility for policy and strategy development, and commissioning of palliative and EOLC services.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the questionnaire survey was that it provided an opportunity for GPs across the UK to participate, hence enabling a nationally relevant picture to emerge. There is uncertainty over the representativeness of responders, however, as it is likely that responders were GPs who are more interested and involved in EOLC, and hence are likely to be more informed than colleagues who are less involved in EOLC.

The design of the questionnaire allowed responders to contribute free-text comments, which enabled expression of a range of issues that went beyond the issues directly assessed within the closed questions. It is recognised that there are inherent limitations in free-text comments from questionnaires as individuals vary in the extent to which they are inclined to contribute comments, reflecting issues such as time to complete the questionnaire, interest in the topic, and strength of view.20 It is possible that further themes would have emerged had the questionnaire been specifically designed to seek views from GPs who are less involved in EOLC.

Comparison with existing literature

There was a strong sense in this questionnaire survey that GPs value having time to be with patients and their families towards the end of life, and that this is needed for the provision of good-quality EOLC. Providing research evidence to support this can be methodologically challenging, but there is evidence to suggest that a positive relationship exists between longitudinal continuity of care between patients and clinicians and patient satisfaction.21,22

The importance of effective MDT working, and the contribution of community nurses who are described as ‘distressingly overstretched’, was widely reflected in the present results and has been described previously.23,24 Community nursing is highly valued by GPs, particularly in terms of building relationships with patients at the end of their lives and with their families, delivering symptom-control medication, completing holistic assessments, and taking a proactive role in advanced care planning discussions. A lack of responsive services, particularly access to hands-on nursing or social care, was also highlighted.

The issues described in this study highlight the resource concerns that currently inhibit the development of a work environment in which the role of GPs and community nurses in EOLC is better recognised and supported, with adequate time resource, facility for close team-working, and access to relevant training enabled.

The study identified tensions in current working practices regarding collaborative working among GPs, OOH services, community nursing, and specialist services. The need for clear communication, effective MDT working, and definition of roles and responsibilities is ongoing.25 Much EOLC occurs during evenings, nights, and at weekends, when the delivery of EOLC can be particularly challenging for a number of possible reasons, including the nature of OOH work, the reasons why GPs work in OOH services, and a feeling of isolation described by GPs working in OOH services within the system.26 Effective, consistent IT communication systems, and sharing of patient records, including handover of sensitive information regarding EOLC, is a continuing need.27,28

The need to consider variability in practice and for more training and professional development emerged, particularly with regard to the early identification of patients with palliative care needs, such that there is opportunity for care planning, recognition and proactive management of the dying patient, and symptom-control and prescribing. These can be complex clinical issues, affected also by the experience and attitudes of individual clinicians. There appears to be ongoing need for improving access to formal education and training opportunities to enhance confidence levels and a more open approach to EOLC.29

Implications for research and practice

The study sought to elicit views of GPs around their experiences of providing EOLC in the community, and did not specifically seek participants’ views on how the barriers can be overcome. The findings are in keeping with those of previous studies, suggesting that there is an ongoing need for practical service development and implementation plans to empower and resource GPs and community teams to deliver high-quality EOLC. In addition, the findings highlight enduring priorities for primary palliative care research.11

The challenges of early identification of the palliative care needs,30,31 successful advance care planning, and care coordination, including with OOH services, are recognised.26,27,32,33 The need for more accessible training and education across primary care is ongoing.34 A focus on partnership working between specialist palliative care and the primary care workforce also needs to be strengthened if the aspirations of recent policy recommendations are to be achieved.6

This study’s findings must be considered in the context of current primary care workload and workforce challenges, changes in primary care organisation, and the increasing needs of the population. Future developments in terms of national strategy and policy recommendations in palliative care must recognise the pressurised environment in which GPs are working. Continued development of tools and systems that are relevant, practical, and user friendly is important, including IT systems. Commissioning approaches that consider the whole healthcare system, including primary care contracting, provide a mechanism by which palliative and EOLC can be developed. Innovative approaches, including engaging with local communities to break down the barriers in conversation about death and dying, provide another valuable strategy towards improving the future provision of EOLC.35

Funding

The questionnaire survey was carried out as part of the RCGP/Marie Curie End-of-Life Care Clinical Priority Workstream of the RGCP Clinical Innovation and Research Centre. No additional funding was sought.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Competing interests

The authors thank all of the GPs who took part in the survey.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Neuberger J. More care, less pathway: a review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. Independent review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. 2013 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212450/Liverpool_Care_Pathway.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman Dying without dignity: investigations by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman into complaints about end of life care. 2015 http://www.ombudsman.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/32167/Dying_without_dignity_report.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murtagh FE, Bausewein C, Verne J, et al. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med. 2014;28(1):49–58. doi: 10.1177/0269216313489367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray S, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1007–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall M, Carduff E, Lloyd A, et al. Different experiences and goals in different advanced diseases: comparing serial interviews with patients with cancer, organ failure, or frailty and their family and professional carers. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2015;50(2):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership. Ambitions for palliative and end of life care: a national framework for local action 2015–2020. http://endoflifecareambitions.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ambitions-for-Palliative-and-End-of-Life-Care.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016)

- 7.NHS Scotland Living and dying well: a national action plan for palliative and end of life care in Scotland. 2008 http://www.gov.scot/resource/doc/239823/0066155.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welsh Government End of life care delivery plan. 2014 http://gov.wales/topics/health/nhswales/plans/end-of-life-care/?lang=en (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health Living matters, dying matters: a palliative and end of life care strategy for adults in Northern Ireland. 2010 https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/living-matters-dying-matters-strategy-2010 (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2002;16(6):457–464. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm573oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, et al. Improving generalist end of life care: national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service user groups. BMJ. 2008;337:a1720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyniers T, Houttekier D, Pasman HR, et al. The family physician’s perceived role in preventing and guiding hospital admissions at the end of life: a focus group study. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):441–446. doi: 10.1370/afm.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Korte-Verhoef MC, Pasman HR, Schweitzer BP, et al. How could hospitalisations at the end of life have been avoided? A qualitative retrospective study of the perspectives of general practitioners, nurses and family carers. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Offen J. The role of UK district nurses in providing care for adult patients with a terminal diagnosis: a meta-ethnography. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21(3):134–141. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pivodic L, Harding R, Calanzani N, et al. Home care by general practitioners for cancer patients in the last 3 months of life: an epidemiological study of quality and associated factors. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):64–74. doi: 10.1177/0269216315589213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royal College of General Practitioners Put patients first Support our campaign. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/put-patients-first.aspx (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS England Five year forward view. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016)

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia J, Evans J, Reshaw M. ‘Is there anything else you would like to tell us’ — methodological issues in the use of free-text comments from postal surveys. Qual Quant. 2004;38:113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saultz J, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):445–451. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman G, Hughes J. Continuity of care and the patient experience. An inquiry into the quality of general practice in England. 2010 http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/continuity-care-patient-experience-gp-inquiry-research-paper-mar11.pdf (accessed 20 Jun 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths J, Ewing G, Wilson C, et al. Breaking bad news about transitions to dying: a qualitative exploration of the role of the district nurse. Palliat Med. 2015;29(2):138–146. doi: 10.1177/0269216314551813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ke LS, Huang X, O’Connor M, et al. Nurses’ views regarding implementing advance care planning for older people: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(15–16):2057–2073. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Factors supporting good partnership working between generalist and specialist palliative care services: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X641474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taubert M, Nelson A. ‘Oh God, not a palliative’: out-of-hours general practitioners within the domain of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):501–509. doi: 10.1177/0269216310368580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leydon GM, Shergill NK, Campion-Smith C, et al. Discontinuity of care at end of life: a qualitative exploration of OOH end of life care. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(4):412–421. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali AA, Adam R, Taylor D, et al. Use of a structured palliative care summary in patients with established cancer is associated with reduced hospital admissions by out-of-hours general practitioners in Grampian. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(4):452–455. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pype P, Peersman W, Wens J, et al. What, how and from whom do health care professionals learn during collaboration in palliative home care: a cross-sectional study in primary palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:501. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell H, Noble S, Finlay I, et al. Defining the palliative care patient: its challenges and implications for service delivery. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(1):46–52. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott M, Nicholson C. A qualitative study exploring use of the surprise question in the care of older people: perceptions of general practitioners and challenges for practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014 Aug 28; doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000679. pii: bmjspcare-2014-000679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adam R, Clausen MG, Hall S, et al. Utilising out-of-hours primary care for assistance with cancer pain: a semi-structured interview study of patient and caregiver experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seymour J, Almack K, Kennedy S. Implementing advance care planning: a qualitative study of community nurses’ views and experiences. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):224–239. doi: 10.1177/0269216315606645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellehear A. The compassionate city charter. In: Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A, editors. Compassionate communities: case studies from Britain and Europe. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015. pp. 76–87. [Google Scholar]