Highlights

-

•

Hepatic Portal Venous Gas (HPVG) is a rare condition often associated with a significant underlying pathologies.

-

•

The mechanism underlying the passage of the gas from the intestine into the mesenteric, then portal, venous system is not fully understood.

-

•

The high mortality rate made HPVG a cause of mandatory explorative laparotomy throughout the last fifty years of the twentieth century.

-

•

The frequent presence of benign conditions underlying this condition has diverted the common therapeutic approach to more cautious options.

Keywords: Portal venous gas, Bowel obstruction, Mesenteric ischemia, Complications abdominal surgery, Computed tomography

Abstract

Introduction

Hepatic Portal Venous Gas (HPVG), a rare condition in which gas accumulates in the portal venous circulation, is often associated with a significant underlying pathology, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, pancreatitis, sepsis, intra-abdominal abscess, endoscopic procedures, mesenteric ischemia, abdominal trauma.

Presentation of case

Here we report a case of HPVG in an 82-year-old patient who underwent a left colectomy for stenosing tumor of the descending colon. The patient was treated conservatively, and his symptoms resolved. Follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan showed complete resolution of HPVG.

Discussion

The mechanism underlying the passage of the gas from the intestine into the mesenteric, then portal, venous system is not fully understood. Historically, this condition has been related to acute intestinal ischemia, as a consequence of a bacterial translocation through a wall defect.

Conclusion

This case underscores the role of conservative management, highlighting how the severity of the prognosis of HPVG should be related to the underlying pathology, and not influenced by the presence of HPVG itself.

1. Introduction

Hepatic Portal Venous Gas (HPVG) is a rare pathological condition associated with several acute abdominal pathologies. It may be considered as a nonspecific sign of a significant abdominal disease, ranging from benign conditions to potentially lethal diseases. Here we present a case of postoperative HPVG, in a patient who underwent a left colectomy for cancer, treated with a conservative approach [12].

2. Case presentation

An 82-year-old Caucasian male patient was admitted to our Institution with as suffering from obstructive colorectal cancer. After performing colonscopy and biopsies and total body CT to confirm diagnosis and to exclude metastasis he underwent. left colectomy. The patient had an regular postoperative period of five days after surgery, then he started to complain of generalized abdominal pain. On physical examination the abdomen showed moderate distention, without tenderness to palpation or signs of peritonism. Blood investigations revealed normal renal and hepatic values, bilirubin value was 16 micromoles/L (<21), ALT 25 (<33), AST 31 (<45), GGT 23 (<30), and ALP 78 (30–115). White cell count was 27.2 × 10/L (3.9–11.1) and hemoglobin value was 14.1 gm/dL with normal coagulation parameters. On postoperative day 9 a contrast-enhanced CT was performed that revealed massive gas within the superior mesenteric vein, the portal venous system and its intrahepatic branches (“pneumoportogram”) (Fig. 1). This condition would have meant either a significant ischemic event or a pneumatosis intestinalis due to ileus and intestinal distention, associated with bacterial proliferation. However we assessed the patient’s clinical condition, that was stable, together to – the absence of clinical and laboratory signs of acute intestinal ischemia, and we decide for a conservative approach. – The patient was treated with total parenteral nutrition and empiric antibiotic therapy to cover potential bacterial translocation, with intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam, and metronidazole, associated with oral mesalazine. He made a dramatic recovery over the course of 48 h. A new CT scan performed seven days later showed complete resolution, with total absence of gas within the portal derivations both extra- and intra-hepatic (Fig. 2). Three weeks after surgery, the patient was discharged and has been well ever since, with no recurrence reported.

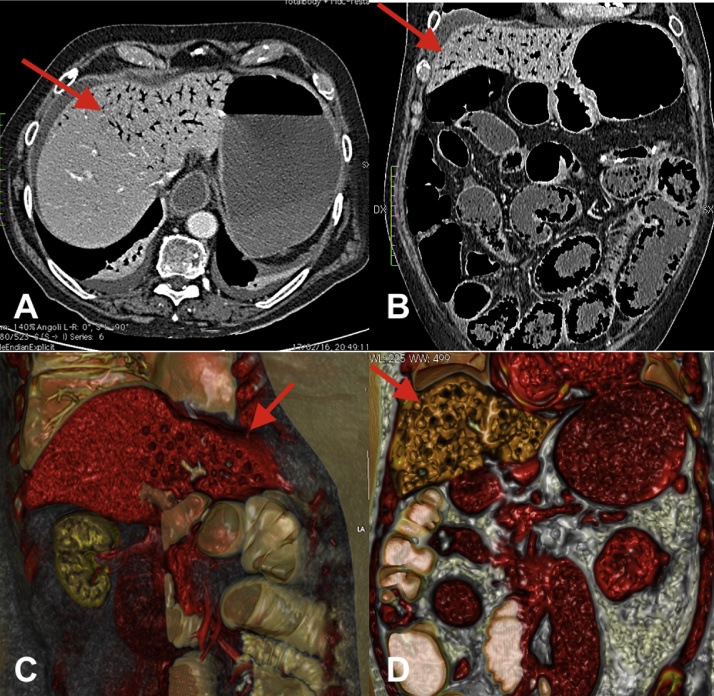

Fig. 1.

(A–D) Abdominal CT scan arterial-phase (sagittal and coronal view, 3D rendering) demonstrating extensive gas within the superior mesenteric vein, the portal venous system and its intrahepatic branches (“pneumoportogram”).

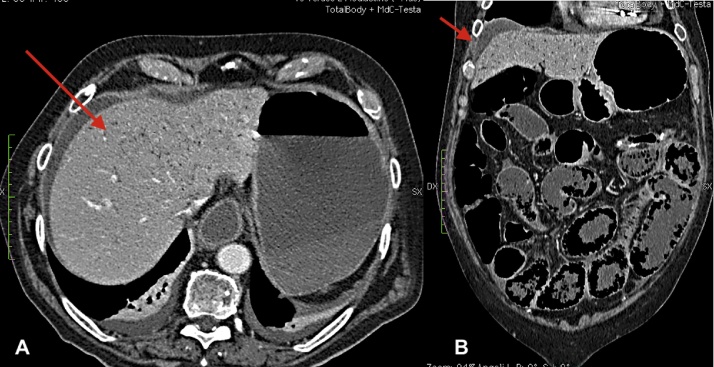

Fig. 2.

(A and B) Abdominal CT scan (sagittal and coronal view), performed seven days later shows total absence of gas within the portal derivations both extra- and intra-hepatic.

3. Discussion

Onset of Hepatic Portal Venous Gas, first described by Wolfe and Evans (1955) in an infant with necrotizing enterocolitis [1], is caused by several etiologies including catastrophic and severe conditions as well as mesenteric ischemia, intestinal obstruction, enteritis, duodenal ulcer perforation, necrotizing pancreatitis, such as more benign causes as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, intra-abdominal abscess, abdominal trauma, abdominal surgery, and finally invasive endoscopic procedures [2], [3], [4]. The mechanism underlying the passage of the gas from the intestine into the mesenteric, then portal, venous system is not fully established. HPVG occurs when intestinal gas enters into mesenteric and portal vein via damaged mucosa layer, due to an increase pressure within intestine resulting from increased intra abdominal pressure. Another possible mechanism involves the proliferation of anaerobic bacteria within the intestine, producing a large amount of gas that enters the venous circulation [4]. Historically, this condition has been related to acute intestinal ischemia, as a consequence of a bacterial translocation through a wall defect. HPVG diagnosis is performed with X-rays, ultrasound examination with Color Doppler Flow imaging or, with a better diagnostic accuracy, through abdominal contrast-enhanced CT. The mortality rate, in the first studies, was up to 75% [2] following bowel necrosis [3] that was the most frequent cause of HPVG within a span of approximately 25 years, the rate of bowel necrosis decreased from 72% to 43% and mortality reduced to 39%. The observed reduction in these parameters were attributed to an increase in the proportion of benign conditions [5]. Case reports of on HPVG associated to benign etiologies have been increasing since 1980 with the increased use of more sensitive diagnostic imaging techniques (ultrasonography and CT). The high mortality rate lead to consider HPVG an indication of mandatory explorative laparotomy throughout the last fifty years [8], [9], [11]. The latter increase incidence of benign conditions HPVG correlated suggest to change the common invasive therapeutic approach to lesser invasive treatment [10]. According to the fact that the presence of HPVG on CT could be associated with a range of non surgical pathologies, its’ presence does not mandate surgical explorative and has no prove predictive power. Surgical intervention in all HPVG cases would result in approximately 30% non therapeutic laparotomies [6]. A current evidence based indication for surgery is bowel ischemia/necrosis with or without mechanical obstruction. Wayne’s [7] algorithm could be a worthwhile score to establish the surgical approach vs conservative treatment in HPVG [4], [6], [7].

HPVG associated with abdominal complication after surgery has rarely been reported. There is a scant literature on HPVG induced by postoperative complication after surgery. Although is a severe and life threatening condition, early detection and sistemic treatment lead to a better patient outcome as in our experience [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11].

4. Conclusion

Although the striking finding of a pneumoportogram on imaging studies might be quite frightening, as in our case, the severity of the prognosis of HPVG should be related to the underlying pathology, and not influenced by the presence of HPVG itself. Because in the last two decades has been observed an increase of benign causes correlated to HPVG which require and resolve with conservative treatment. Indications for surgical and non-surgical management of HPVG, including associated complications and mortality remain to be clarified.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no substantial direct or indirect commercial financial incentive associated with publishing the manuscript.

Funding for your research

The study sponsors had no such involvement.

Ethical approval

Whether approval by Instituitional Board has been given for this case report.

Consent

Informed consent was abtained from the patient; all authors ensure that all text and images alterations to protect anonymity do not distort scientific mean of the manuscript.

Author contribution

Giorgio C. Ginesu: Writing paper.

Michele Barmina: Writing paper.

Maria L. Cossu: data analysis.

Claudio F. Feo: Text edit.

Francesca Addis: data collection.

Alessandro Fancellu: data anlysis.

Alberto Porcu: text edit.

Guarantor

Giorgio C. Ginesu.

Contributor Information

G.C. Ginesu, Email: ginesugc@uniss.it, edosec@yahoo.it.

M. Barmina, Email: michelebarmina@gmail.com.

M.L. Cossu, Email: mlcossu@uniss.it.

C.F. Feo, Email: cffeo@uniss.it.

A. Fancellu, Email: afancel@uniss.it.

F. Addis, Email: fra.addis49@gmail.com.

A. Porcu, Email: alb.porcu@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Wolf J.N., Evans W.A. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants: a roentgenographic demontration with postmortem anatomical correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1955;74:486–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liebman P.R., Patten M.T., Manny J., Benfield J.R., Hechtman H.B. Hepatic portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann. Surg. 1978;187:281–287. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197803000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesarwani V., Ghelani D.R., Reece G. Hepatic portal venous gas: a case report and review of literature. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2009;13(April–June (2)):99–102. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.56058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo S.K., Park J.H., Know S.H. Clinical outcome in surgical and non-surgical management of hepatic portal venous gas. Korean J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2015;19(November (4)):181–187. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2015.19.4.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solakoglu T., Sari S.O., Koseoglu H., Basaran M., Akar M., Buyukasik S., Ersoy O. A case of hepatic portal venous gas after colonscopy. Arab J. Gastroenterol. 2016;17:140–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moser A., Stauffer A., Wyss A., Schneider C., Essig M., Radke A. Conservative treatment of hepatic venous gas consecutive to a complicated diverticulitis: a case report in literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016;23:186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wayne E., Ough A., Wu A. Management algorithm for pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas: treatment and outcome of 88 consecutive cases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010;14(3):437–448. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okaka S., Azuma T., Kawashita Y., Matsuo S., Eguchi S. Clinical evaluate of hepatic portal venous gas after abdominal surgery. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2016;10(January–April (1)):99–107. doi: 10.1159/000444444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cossu M.L., Meloni G.B., Alagna S., Tilocca P.L., Pilo L., Profili S., Noya G. Emergency surgical conditions after biliopancreatic diversion. Obes. Surg. 2007;17(May (5)):637-. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevins E.J., Moori P., Ward C.S.J., Murphy K., Elmas C.S., Taylor J.V. A rare case of ischemic pneumatosis intestinalis and hepatic portal venous gas in an elderly patient with good outcome following conservative management. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016;25:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGregor A., Beckdache K., Choi L. Idiopathic Pneumatosis Intestinalis Requiring Decompressive Laparotomy. Conn. Med. 2016;80(5):301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. (article in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]