Abstract

Purpose

The course of quality of life after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer is not well understood. We aimed to identify subgroups of gynecologic cancer patients with distinct trajectories of quality of life outcomes in the 18-month period after diagnosis. We also aimed to determine whether these subgroups could be distinguished by predictors derived from Social-Cognitive Processing Theory.

Methods

Gynecologic cancer patients randomized to usual care as part of a psychological intervention trial (NCT01951807) reported on depressed mood, quality of life, and physical impairment soon after diagnosis and at five additional assessments ending 18 months after baseline. Clinical, demographic, and psychosocial predictors were assessed at baseline, and additional clinical factors were assessed between 6–18 months after baseline.

Results

A two-group growth mixture model provided the best and most interpretable fit to the data for all three outcomes. One class revealed subclinical and improving scores for mood, quality of life, and physical function across 18 months. A second class represented approximately 12% of patients with persisting depression, diminished quality of life, and greater physical disability. Membership of this high-risk subgroup was associated with holding back concerns, more intrusive thoughts, and use of pain medications at the baseline assessment (ps < .05).

Conclusions

Trajectories of quality of life outcomes were identified in the 18-month period after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Potentially modifiable psychosocial risk factors were identified that can have implications for preventing quality of life disruptions and treating impaired quality of life in future research.

Keywords: gynecologic neoplasms, quality of life, depression, physical impairment, growth mixture modeling

Introduction

Gynecologic cancer and its treatment adversely affect quality of life (QOL) outcomes, such as mood, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and physical functioning. Although overall QOL improves over time in most gynecologic cancer patients [1, 2], many survivors continue to report significant depressive symptoms, reduced HRQOL, and physical impairment [3].

One important gap in the literature is data to predict which women diagnosed with gynecologic cancer are at greatest risk for these negative sequelae. No studies to date have identified subgroups of gynecologic cancer patients with distinct QOL trajectories. These analyses can identify subsets of patients who exhibit similar patterns in QOL over time and can provide a more detailed understanding than what is possible with typical longitudinal analyses. Understanding the predictors of and changes in QOL outcomes can help clinicians identify patients in need of psychological intervention and targets for intervention.

It is important to examine relevant theoretical models when identifying risk factors for impaired QOL. One relevant theory is Social-Cognitive Processing Theory [4, 5], which posits that successfully adapting to a stressful situation involves sharing one’s concerns with others and assimilating life experience into one’s world view (social and cognitive processing, respectively). With respect to social processing, many cancer patients hold back from disclosing their concerns due to unsupportive behavior they experience from others (e.g., criticizing patients) [6–13]. Unsupportive behaviors from friends and family as well as holding back from sharing concerns are associated with worse QOL [6, 14–16]. QOL in cancer patients has also been linked with cognitive processes, including more benefit finding, perceived coping efficacy, using adaptive coping strategies, as well as fewer intrusive thoughts [2, 6, 17–19]. Thus, social and cognitive processing constructs should be studied as predictors of QOL trajectories in gynecologic cancer patients.

In addition, it is important to consider the impact of clinical factors when examining change over time in QOL. Factors such as disease stage at diagnosis and disease recurrence have been shown to impact QOL [20–22]. However, evidence is mixed with some studies showing no association between clinical factors and QOL [23, 24].

This study aimed to identify subgroups of gynecologic cancer patients with distinct trajectories in QOL in the 18 months after diagnosis. We also aimed to identify demographic, clinical, and psychosocial predictors of subgroup membership. We hypothesized that a worse QOL trajectory would be associated with greater holding back, greater unsupportive behavior from family and friends, less benefit finding, lower coping efficacy, more intrusive thoughts, more avoidance, and less use of adaptive coping strategies.

Method

Participants

Participants were women randomized to the usual care in a randomized clinical trial evaluating two psychological interventions for gynecologic cancer patients (NCT01951807). Usual care consisted of psychosocial care offered to patients in the medical center where they were being treated (e.g., psychiatric consultation, psychosocial care, social work services). Eligible women had primary gynecologic cancer (ovarian, endometrial/uterine, cervical, vulvar, or fallopian tube) and were undergoing treatment at one of seven hospitals in the northeastern United States. Participants were required to: be ≥18 years of age, be diagnosed within the previous 6 months, be ambulatory and capable of self-care (KPS≥80 or ECOG≤1), speak English, have no hearing impairment, and live within a 2-hour commute from a recruitment center.

Procedure

Eligible participants were identified via chart review, sent a letter describing the study, and contacted by study staff in person or by phone. Participants signed a consent form approved by an Institutional Review Board. Self-report questionnaires were completed at study entry, five weeks, nine weeks, six months, 12 months, and 18 months after study entry. Participants were paid $15 for each survey completed. Outcomes were assessed at each assessment and potential predictors were assessed at baseline with the exception of clinical factors at or after the six-month assessment.

Measures

Demographics and Clinical Factors

Participants completed demographics questionnaires that assessed age, racial/ethnic background, education, marital status, and household income. Chart reviews assessed the following baseline variables: type of cancer, time since diagnosis, presence of metastasis at diagnosis, cancer treatment history, menopausal status, and use of medication for pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance. In addition, the presence of disease progression and/or recurrence as well as treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation beyond six months after diagnosis was assessed in follow-up chart reviews.

Outcomes

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms [25]. Participants are asked to endorse statements about feelings such as sadness, loss of pleasure, and irritability on a 4-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptomatology. The BDI is widely used in cancer populations and has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability [26, 27]. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α range=.84–.92). Scores ≤9, 10–18, 19–29, and 30–63 suggest minimal, mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms, respectively [27]. We used a cut score of 0.5 standard deviations (3.6 points in this sample) to determine clinically-important change in depressive symptomatology [28].

Health-Related Quality of Life

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) assesses HRQOL with items on a 5-point scale [29]. Items are summed to produce an overall HRQOL score, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL. The FACT-G is widely used in cancer populations and has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability [29–32]. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α range=.91–.94). A normative cancer population score (80) and a minimally important difference score (7) have been established [33, 34].

Physical Impairment

The 26-item Physical Function subscale of the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System asks respondents to report on physical limitations they experience on a 5-point scale [35]. Scores are averaged to produce a Physical Impairment summary score, with higher scores indicating greater physical impairment. This scale is widely used in cancer populations and has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability [35–37]. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α range=.92–.96). We used a cut score of 0.5 standard deviations (9.6 points in this sample) to determine clinically important change in depressive symptomatology [28].

Social Processing Constructs

Holding Back From Sharing Concerns

A 13-item scale was used that measures the degree to which participants hold back from family and friends [15]. Participants are asked to rate, on a 6-point scale, the degree to which they hold back from discussing issues of concern with friends and family. Scores are averaged to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating greater holding back. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α=.93).

Unsupportive Behaviors from Family and Friends

The Cancer Support Inventory is a 13-item scale that measures the degree to which family and friends respond to patients in ways that are unsupportive [38]. The measure asks respondents to rate the frequency of unsupportive responses. Scores are summed, with higher scores indicating greater unsupportive behavior from family and friends. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α=.99).

Cognitive Processing Constructs

Benefit Finding

The 17-item Benefit Finding Scale measures how much participants feel their cancer and its treatment have made positive contributions in their lives [39, 40]. Respondents are asked to rate their agreement with statements of possible benefits from cancer and its treatment. Scores are averaged to produce a summary score, with higher scores indicating greater benefit finding. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α=.94).

Coping Efficacy

A 17-item scale was used to measure confidence in coping skills on a 5-point scale [16]. Respondents are asked to rate their ability to practice various coping strategies on a 5-point scale. Scores are summed to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating greater coping efficacy. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α=.94).

Intrusion and Avoidance

The Intrusion and Avoidance subscales of the 15-item Impact of Events Scale were used. These subscales ask respondents to rate, on a 4-point scale, the frequency with which they experienced intrusive thoughts related to their cancer and avoided thinking about their cancer [41]. Scores are summed to produce summary scores, with higher scores indicating more intrusive thoughts and greater avoidance. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α range=.83–.87).

Positive reinterpretation and Planning Coping

The Positive Reinterpretation and Growth subscale and the Planning subscale of the COPE Inventory were used to measure use of adaptive coping strategies [42]. These subscales ask respondents to rate the degree to which they use several coping strategies on a 4-point scale. Scores are summed to produce a total score for each subscale, with higher scores indicating greater use of active coping strategies. Internal consistency in the current study was adequate (α range=.88–.91).

Statistical Analysis

Consistent with established best practices [43] and previous cancer research [19], changes over time in each outcome were modeled separately using a three-stage procedure. First, changes in outcomes across the study period were modeled using mixed models which identified whether the overall sample demonstrated change over time. Second, growth mixture modeling was used to iteratively extract classes of participants with similar trajectories of change over time. We examined the fit of each model using the −2 log likelihood (−2LL) ratio test, the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Vuong-Lo-Mendel Rubin likelihood ratio test, and Entropy. After the best-fitting, most theoretically relevant, and most interpretable model was obtained for each outcome, univariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify predictors of class membership. All risk factors that were significant at p<.05 were simultaneously included in multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the contribution of these risk factors in predicting class membership.

Lastly, Cohen’s kappa tests were conducted to determine whether there was significant overlap in membership across outcomes. This test produces a kappa value with values ranging from 0–1, with higher values indicating greater overlap.

Results

Participants

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Briefly, participants averaged 56 years of age, 77% were Caucasian, and 82% had attended some college. Most participants (73%) were married. The average time from diagnosis to consent was 3.8 months. Most were diagnosed with ovarian cancer (60%); the remainder were diagnosed with fallopian tube cancer (14%), endometrial cancer (12%), uterine cancer (7%), cervical cancer (5%), or other gynecologic cancers (2%). Most participants had ≥stage III disease (76%). At the time of diagnosis, 89% were receiving chemotherapy and 7% were receiving radiotherapy. Most (73%) had completed treatment by their 6-month assessment.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical factors as univariate predictors of class membership.

| Total Sample N=124 |

Depression | QOL | Physical Function | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (n=15) | Class 2 (n=109) | p | Class 1 (n=11) | Class 2 (n=93) | p | Class 1 (n=15) | Class 2 (n=109) | p | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age (X±SD) | 56±10 | 57±10 | 54±8 | .37 | 56±10 | 51±8 | .11 | 57±10 | 55±10 | .59 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| White/Caucasian | 96 (77%) | 10 (67%) | 86 (79%) | .33 | 7 (64%) | 18 (19%) | .24 | 11 (73%) | 85 (78%) | .74 |

| Other | 28 (23%) | 5 (33%) | 23 (21%) | 4 (36%) | 75 (81%) | 4 (27%) | 24 (22%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| ≤ High school degree | 22 (18%) | 17 (16%) | 5 (33%) | .14 | 2 (18%) | 12 (13%) | .64 | 3 (20%) | 19 (17%) | .73 |

| ≥ Some college | 102 (82%) | 92 (84%) | 10 (67%) | 9 (82%) | 81 (87%) | 12 (80%) | 90 (83%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| Not married | 34 (27%) | 28 (26%) | 6 (40%) | .35 | 5 (45%) | 18 (19%) | .06 | 8 (53%) | 26 (24%) | .03 |

| Married | 90 (73%) | 81 (74%) | 9 (60%) | 6 (55%) | 75 (81%) | 7 (47%) | 83 (76%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Household income | ||||||||||

| ≤ $49,999 per year | 47 (38%) | 39 (36%) | 8 (53%) | .26 | 6 (55%) | 31 (33%) | .19 | 8 (53%) | 39 (36%) | .26 |

| ≥ $50,000 per year | 77 (62%) | 70 (64%) | 7 (47%) | 5 (45%) | 62 (67%) | 7 (47%) | 70 (64%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Gynecologic Cancer Diagnosis | .33 | .39 | .12 | |||||||

| Ovarian | 75 (60%) | 11 (73%) | 64 (59%) | 9 (82%) | 53 (57%) | 10 (66%) | 65 (60%) | |||

| Fallopian | 17 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 15 (14%) | 1 (9%) | 13 (14%) | 1 (7%) | 16 (14%) | |||

| Endometrial | 15 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (15%) | 1 (7%) | 14 (13%) | |||

| Uterine | 8 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (7%) | |||

| Cervical | 6 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (5%) | |||

| Other | 3 (2%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (1%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Months since diagnosis (X±SD) | 3.8±1.7 | 3.8±1.7 | 4.2±2.0 | .40 | 3.7±1.6 | 3.2±1.7 | .32 | 3.8±1.7 | 4.0±1.8 | .74 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Menopausal status | ||||||||||

| Premenopausal | 11 (9%) | 1 (7%) | 10 (9%) | 2 (18%) | 9 (10%) | 2 (13%) | 9 (8%) | |||

| Perimenopausal | 7 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 6 (5%) | .94 | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) | .51 | 0 (0%) | 7 (6%) | .51 |

| Postmenopausal | 100 (80%) | 12 (79%) | 88 (81%) | 8 (73%) | 75 (81%) | 12 (80%) | 88 (81%) | |||

| Missing | 6 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (9%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (5%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Chemotherapy at baseline | ||||||||||

| No | 13 (11%) | 2 (13%) | 11 (10%) | .67 | 1 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 0.99 | 3 (20%) | 10 (9%) | .21 |

| Yes | 107 (86%) | 13 (87%) | 94 (86%) | 10 (91%) | 82 (88%) | 12 (80%) | 95 (87%) | |||

| Missing | 4 (3%) | — | 4 (4%) | — | 4 (4%) | — | 4 (4%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Radiation at baseline | ||||||||||

| No | 113 (91%) | 15 (100%) | 98 (90%) | 11 (100%) | 83 (89%) | 14 (93%) | 99 (91%) | |||

| Yes | 9 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (8%) | .60 | 0 (0%) | 8 (9)% | 0.59 | 1 (7%) | 8 (7%) | .99 |

| Missing | 2 (2%) | — | 2 (2%) | — | 2 (2%) | — | 2 (2%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Surgery | ||||||||||

| TAHBSO | 93 (75%) | 10 (67%) | 83 (76%) | .46 | 8 (73%) | 69 (74%) | >.99 | 3 (20%) | 16 (15%) | .43 |

| Other/None | 19 (15%) | 3 (20%) | 16 (15%) | 2 (18%) | 16 (17%) | 9 (60%) | 84 (77%) | |||

| Missing | 12 (10%) | 2 (13%) | 10 (9%) | 1 (9%) | 8 (9%) | 3 (20%) | 9 (8%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Distant metastasis present | ||||||||||

| No | 112 (90%) | 14 (93%) | 98 (90%) | >.99 | 10 (91%) | 84 (90%) | >.99 | 14 (93%) | 98 (90%) | >.99 |

| Yes | 12 (10%) | 1 (7%) | 11 (10%) | 1 (9%) | 9 (10%) | 1 (7%) | 11 (10%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Taking pain medication | ||||||||||

| No | 90 (72%) | 6 (40%) | 84 (77%) | <.01 | 4 (36%) | 70 (75%) | .01 | 6 (40%) | 84 (77%) | <.01 |

| Yes | 32 (26%) | 9 (60%) | 23 (21%) | 7 (64%) | 21 (23%) | 9 (60%) | 23 (21%) | |||

| Missing | 2 (2%) | — | 2 (2%) | — | — | — | 2 (2%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Taking depression medication | ||||||||||

| No | 94 (75%) | 12 (80%) | 82 (75%) | >.99 | 9 (82%) | 70 (75%) | >.99 | 11 (73%) | 83 (76%) | >.99 |

| Yes | 27 (22%) | 3 (20%) | 24 (22%) | 2 (18%) | 21 (23%) | 3 (20%) | 24 (22%) | |||

| Missing | 3 (2%) | — | 3 (3%) | — | — | 1 (7%) | 2 (2%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Taking anxiety medication | ||||||||||

| No | 74 (60%) | 9 (60%) | 65 (60%) | >.99 | 4 (36%) | 58 (62%) | .10 | 9 (60%) | 65 (60%) | >.99 |

| Yes | 47 (38%) | 6 (40%) | 41 (38%) | 7 (64%) | 32 (35%) | 6 (40%) | 41 (37%) | |||

| Missing | 3 (2%) | — | 3 (3%) | — | 3 (3%) | — | 3 (3%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Taking sleep medication | ||||||||||

| No | 100 (81%) | 13 (87%) | 87 (80%) | >.99 | 74 (80%) | 10 (91%) | .69 | 87 (80%) | 13 (87%) | >.99 |

| Yes | 21 (17%) | 2 (13%) | 19 (17%) | 16 (17%) | 1 (9%) | 19 (17%) | 2 (13%) | |||

| Missing | 3 (2%) | — | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | — | 3 (3%) | — | |||

Of the 1,545 potentially eligible patients approached, 82 were deemed ineligible before consent and 372 consented to the larger randomized clinical trial (25%). Of these, 124 were assigned to the Usual Care arm and included in this study. Common reasons for refusal included the patient felt she lived too far from the site (14%), was overwhelmed (10%), or would not benefit from the study (9%). Participants were younger than refusers (Mparticipants=56, Mrefusers=60 years; p<.01), but these groups did not differ on time since diagnosis, type of cancer (ovarian vs. other), stage of disease, or race/ethnicity (ps≥.10).

Change Over Time in Outcomes

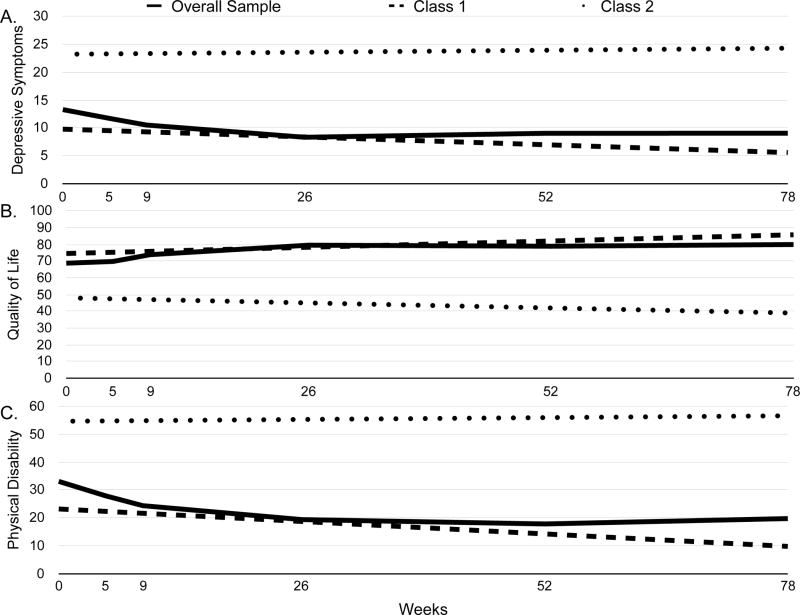

Visual and statistical analysis revealed that depression, HRQOL, and physical impairment were best described using linear rather than quadratic or cubic models. Growth mixture modeling resulted in two-class models selected as the final models for each outcome (see Table 2). Figure 1 for provides estimated mean scores, and Table 3 provides parameter estimates for each outcome in each class. On average, the sample displayed significant decreases in depressive symptoms, increases in HRQOL, and decreases in physical impairment (ps<.01).

Table 2.

Summary of statistical fit indices.

| Number of Classes | AIC | BIC | −2LL | Free parameters | Entropy | LMR p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1 | 3858.71 | 3889.74 | 1918.34 | 11 | — | — |

| 2 | 3829.77 | 3869.25 | 1900.89 | 14 | .90 | <.01 | |

| 3 | 3816.75 | 3864.69 | 1891.37 | 17 | .85 | .46 | |

| Quality of Life | 1 | 3422.00 | 3451.09 | 1700.00 | 11 | — | — |

| 2 | 3414.23 | 3451.26 | 1693.12 | 14 | .85 | .05 | |

| 3 | 3413.00 | 3457.96 | 1689.50 | 17 | .77 | .37 | |

| Physical Disability | 1 | 4964.10 | 4995.13 | 2471.05 | 11 | — | — |

| 2 | 4928.59 | 4968.08 | 2450.30 | 14 | .90 | <.01 | |

| 3 | 4903.03 | 4950.97 | 2434.51 | 17 | .85 | .02 |

Figure 1.

Estimated means of (A) depression, (B) quality of life, and (C) physical disability scores for the overall sample and each patient class.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for growth mixture models.

| Class | % of Sample | Fixed Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (SE) | 95% CI | Slope (SE) | 95% CI | |||

| Depression | 1 | 88% | 9.79 (0.58)*** | 8.66 to 10.93 | −0.05 (0.01)*** | −0.07 to −0.04 |

| 2 | 12% | 23.22 (1.27)*** | 20.73 to 25.72 | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.04 to 0.07 | |

| Quality of Life | 1 | 89% | 74.54 (1.72)*** | 71.18 to 77.91 | 0.14 (0.03)*** | 0.10 to 0.19 |

| 2 | 11% | 48.04 (3.03)*** | 42.10 to 53.98 | −0.12 (0.06) | −0.23 to 0.02 | |

| Physical Disability | 1 | 88% | 23.17 (15.93)*** | 20.32 to 26.02 | −0.17 (0.03)*** | −0.23 to −0.11 |

| 2 | 12% | 54.61 (3.88)*** | 47.01 to 62.22 | 0.03 (0.06) | −0.10 to 0.15 | |

Depressive Symptoms

Class 1 comprised 88% and Class 2 comprised 12% of the sample. Class 2 (M=23.22) reported significantly worse depressive symptomatology than Class 1 (M=9.79) at baseline, as evidence by their non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals in Table 3. The statistically significant slope for Class 1 indicates that depressive symptoms reduced by approximately 4 points over the course of the 18-month follow-up period Class 1. Class 2 did not report significant change over time in depressive symptoms.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Class 1 comprised 89% and Class 2 comprised 11% of the sample. At baseline, HRQOL was significantly worse for Class 2 (M=48.04) than for Class 1 (M=74.54). Class 1 also reported an improvement in HRQOL by approximately 11 points over the course of the 18-month follow-up period, but HRQOL did not change significantly over time in Class 2.

Physical Impairment

Class 1 comprised 88% and Class 2 comprised 12% of the sample. As with depression and QOL, Class 2 (M=54.61) reported significantly greater physical impairment at baseline than Class 1 (M=23.17). Class 1 reported physical impairment scores improving by approximately 13 points over the 18-month follow-up period, whereas Class 2 reported no change over time in physical impairment.

Predictors of Class Membership

Results from univariate analyses of potential demographic and clinical predictors are presented in Table 1. Results for psychosocial predictors are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Psychosocial factors as univariate predictors of class membership.

| Predictor | Total Sample N=124 |

Depression | QOL | Physical Function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (n=109) | Class 2 (n=15) | p | Class 1 (n=93) | Class 2 (n=11) | p | Class 1 (n=109) | Class 2 (n=15) | p | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Religious/pastoral counseling | ||||||||||

| None in past month | 110 (89%) | 95 (87%) | 15 (100%) | .36 | 83 (89%) | 11 (100%) | .59 | 95 (87%) | 15 (100%) | .36 |

| Used in past month | 13 (10%) | 13 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Missing | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | — | 1 (1%) | — | 1 (1%) | — | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Other psychosocial services | ||||||||||

| None in past month | 92 (74%) | 83 (76%) | 9 (60%) | .21 | 72 (77%) | 7 (64%) | .45 | 84 (77%) | 8 (53%) | .06 |

| Used in past month | 32 (26% | 26 (24%) | 6 (40%) | 21 (23%) | 4 (36%) | 25 (23%) | 7 (47%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Psychotropic medications | ||||||||||

| None in the past month | 53 (43%) | 48 (44%) | 5 (33%) | .58 | 37 (40%) | 5 (45%) | .76 | 49 (45%) | 4 (27%) | .27 |

| Used in the past month | 70 (56%) | 60 (55%) | 10 (66%) | 55 (59%) | 6 (55%) | 59 (54%) | 11 (73%) | |||

| Missing | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | — | 1 (1%) | — | 1 (1%) | — | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Holding Back | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.2) | <.01 | 2.0 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.0) | <.01 | 2.0 (1.3) | 3.3 (0.9) | <.01 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Unsupportive Behavior From Family and Friends | 16.3 (5.0) | 15.7 (4.2) | 21.2 (7.6) | <.01 | 15.9 (4.6) | 22.5 (6.3) | <.01 | 15.9 (4.8) | 19.4 (5.5) | .02 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Benefit Finding | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.61 | 3.4 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) | 0.03 | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.9) | .29 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Coping Efficacy | 53.2 (13.9) | 54.3 (13.9) | 45.6 (11.5) | 0.03 | 53.7 (13.7) | 42.2 (8.5) | 0.01 | 54.0 (14.0) | 47.9 (11.9) | .12 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Intrusive Thoughts | 12.7 (8.9) | 11.2 (8.1) | 23.7 (7.3) | <.01 | 12.6 (13.7) | 20.5 (7.5) | 0.01 | 11.7 (8.5) | 20.5 (8.1) | <.01 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Avoidance | 16.4 (9.5) | 15.4 (9.2) | 23.4 (8.7) | <.01 | 16.2 (9.4) | 22.3 (8.5) | 0.05 | 15.6 (9.5) | 22.1 (7.3) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||||

| COPE: Positive Reinterpretation | 11.2 (3.8) | 11.3 (3.9) | 10.7 (3.4) | 0.62 | 11.3 (3.9) | 10.1 (3.0) | 0.33 | 11.3 (3.9) | 10.5 (3.1) | .47 |

|

| ||||||||||

| COPE: Planning | 11.2 (3.8) | 11.2 (3.8) | 11.0 (4.2) | 0.85 | 11.4 (3.7) | 9.9 (3.6) | 0.21 | 11.3 (3.9) | 10.5 (3.3) | .45 |

Depression

Patients taking pain medication and those reporting more holding back, lower coping efficacy, more intrusive thoughts, and greater avoidance were more likely to be in depression Class 2. In addition to those results presented in Table 1, depression class membership was not associated with receipt of chemotherapy or radiation, disease progression, or recurrence at or after the six-month assessment (ps≥.16). Significant predictors were entered simultaneously into a logistic regression model predicting depression class membership. The Nagelkerke R2 value indicated that the model predicted 54% of the variability in depression class membership. Use of pain medication and more intrusive thoughts remained significant predictors (ps≤.01) and greater holding back marginally predicted (p=.09) membership in the class of women with worse depressive symptoms.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Patients taking pain medication as well as those reporting more holding back, less benefit finding, less coping efficacy, more intrusive thoughts, and greater avoidance were more likely to be in HRQOL Class 2. In addition, HRQOL class membership was not associated with receipt of chemotherapy or radiation, disease progression, or recurrence at or after the six-month assessment (ps≥.16). Significant predictors were entered simultaneously into a logistic regression model predicting HRQOL class membership. The model predicted 57% of the variability in HRQOL class membership. Use of pain medication, greater holding back, greater benefit finding, and more intrusive thoughts remained significant predictors of membership in the class of women with worse HRQOL (ps≤.04).

Physical Impairment

Patients taking pain medication, who were not married, and reporting more holding back, more intrusive thoughts, and greater avoidance were more likely to be in physical impairment Class 2. In addition, physical impairment class membership was not associated with receipt of chemotherapy or radiation, disease progression, or recurrence at or after the six-month assessment (ps≥.09). Significant predictors were entered into a logistic regression model predicting physical impairment class membership. The model predicted 39% of the variability in physical impairment class membership. Use of pain medication, greater holding back, and more intrusive thoughts remained significant predictors of membership in the class of women with worse physical impairment (ps≤.02).

Overlap in Class Membership

Participants’ class memberships significantly overlapped across outcomes. Kappa values ranged from .55 (SE=.12) to .77 (SE=.10) and were all significantly greater than zero (ps<.05). These results indicate that, for example, women in depression Class 1 were more likely to be HRQOL Class 1 than would be expected by chance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine subgroup trajectories of depressive symptoms, HRQOL, or physical disability following diagnosis of gynecological cancer or to examine the demographic, medical, and social and cognitive processing constructs associated with these subgroup trajectories. Three major findings warrant discussion. First, our outcomes were characterized by two subgroups. Most participants reporting levels of QOL that were within normal limits and improved during follow-up; a subgroup reported persistently low QOL. These findings are in line with previous longitudinal studies showing that, on average, QOL improves after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer [17]. Our study extends this by identify a subgroup of women who report persistently elevated depressive symptoms, HRQOL below normal limits, and more physical impairment. This subgroup reported stable and clinically significant depressive symptoms as well HRQOL values that were significantly below norms and remained stable. The larger subgroup of patients reported subclinical levels of depressed mood and normative levels of HRQOL at baseline, and the improvement in both outcomes exceeded the cutoff for clinical significance. Normative values for the physical impairment measure are unavailable; however, a subgroup of patients reported significantly worse physical impairment than the larger group of gynecologic cancer patients and worse physical impairment than a previous cohort of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients [44].

The second major finding was that social and cognitive processing constructs were significant predictors of class membership. Our findings that holding back and intrusive thoughts were associated with worse HRQOL and physical impairment support Social-Cognitive Processing Theory in that they adversely impact psychosocial adaptation [13]. Benefit finding has not been well studied among women with gynecological cancer, but there is a growing body of work suggesting that finding benefit in the cancer experience is associated with better outcomes for cancer patients [45–48]. The lack of an association between benefit finding and depression and physical impairment trajectories suggest that the role of benefit finding may be less strong than holding back and intrusions for these outcomes. We also found that women taking pain medication were more likely to have worse QOL, which is consistent with the longstanding literature showing strong associations between pain and QOL among cancer patients [49–51]. These findings may be helpful to clinicians in identifying those gynecologic cancer patients at greatest risk of impaired QOL. In addition, future research should develop and test interventions targeted to patients who are at elevated risk of impaired QOL.

The third major finding was a significant overlap in membership across outcomes, suggesting, for example, that women with worse depression trajectories were also more likely to exhibit worse trajectories of HRQOL and physical impairment. This is a major strength of the current study, which is among the first to examine subgroup trajectories of multiple outcomes in any cancer population. The finding of a similar sized and significantly overlapping group of women with negative QOL trajectories, all of which were predicted by Social-Cognitive Processing Theory constructs, further supports this model in the context of cancer survivorship. Additional strengths of this study include examination of theoretically based predictors, a focus on a population with significant psychosocial needs, a clinically relevant follow-up period starting soon after diagnosis, and a long follow-up period.

This study also had some limitations. The timing of our assessments may have affected the trajectories observed. Most of participants had ovarian cancer and were White, well educated, and earned at least $50,000 per year, thereby limiting the generalizability of these findings to other populations. Lastly, the sample consisted of women who agreed to participate in a psychological intervention trial.

With regard to clinical applications, psycho-oncology clinics could aim to predict QOL trajectories of gynecologic cancer patients using holding back concerns, intrusive thoughts, and use of pain medications as predictors. Use of pain medications can be easily assessed via electronic medical records or by inquiring with patients. Cancer-related distress can be assessed using such items as the 8-item Intrusion subscale of the Impact of Events Scale [41]. The 13-item holding back measure used in this study could also be helpful for assessing holding back concerns among gynecologic cancer patients [15].

In summary, growth mixture modeling identified classes of women with distinct trajectories of longitudinal depression, HRQOL, and physical functioning. We also found clinical and psychological risk factors that clinicians may screen for and intervene upon in order to try to improve outcomes for the subset of patients at greatest risk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01CA85566 (PI: Manne) and R01CA185623-S1 (PI: Bandera) from the National Cancer Institute.

We wish to acknowledge Sara Frederick, Tina Gadja, Shira Hichenberg, and Kristen Sorice for study management, Joanna Crincoli, Katie Darabos, Lauren Faust, Rebecca Henderson, Sloan Harrison, Travis Logan, Kellie McWilliams, Marie Plaisme, Danielle Ryan, Arielle Schwerd, Kaitlyn Smith, Nicole Teitelbaum, and Amanda Viner for collection of study data. We thank the oncologists and nurses at all five cancer centers for allowing access to patients. Finally, we thank the study participants and therapists for their time.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Greimel E, Thiel I, Peintinger F, Cegnar I, Pongratz E. Prospective assessment of quality of life of female cancer patients. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;85:140–147. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Ullrich P, Johnsen EL, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Ritchie J. Quality of life and mood in women with gynecologic cancer. Cancer. 2002;94:131–140. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roland KB, Rodriguez JL, Patterson JR, Trivers KF. A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:2408–2418. doi: 10.1002/pon.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creamer M, Burgess P, Pattison P. Cognitive processing in post-trauma reactions: some preliminary findings. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20:597–604. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G. Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2007;26:735. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Grana G, Fox K. Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: Patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology. 2005;24:635. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dakof GA, Taylor SE. Victims’ perceptions of social support: what is helpful from whom? Journal of personality and social psychology. 1990;58:80. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopman C, Hermanson K, Diamond S, Angell K, Spiegel D. Social support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:101–111. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199803/04)7:2<101::AID-PON299>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norton TR, Manne SL, Rubin S, Hernandez E, Carlson J, Bergman C, Rosenblum N. Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: the role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychology. 2005;24:143. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badr H, Carmack CL, Kashy DA, Cristofanilli M, Revenson TA. Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2010;29:169. doi: 10.1037/a0018165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manne S, Badr H, Zaider T, Nelson C, Kissane D. Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4:74–85. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepore SJ. A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen B, editors. Psychological interventions for cancer. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 2001. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueiredo MI, Fries E, Ingram KM. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:96–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, Faber M. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:1030–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers SB, Manne SL, Kissane DW, Ozga M, Kashy DA, Rubin S, Heckman C, Rosenblum N, Morgan M, Graff JJ. Social–cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecologic Oncology. 2013;128:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Rothrock N, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI. Quality of life and mood in women receiving extensive chemotherapy for gynecologic cancer. Cancer. 2000;89:1402–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Rothrock NE, Anderson B. Coping and quality of life among women extensively treated for gynecologic cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:132–142. doi: 10.1002/pon.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donovan KA, Gonzalez BD, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB. Depressive Symptom Trajectories During and After Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9550-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Irwin ML, Ferrucci LM, McCorkle R, Ercolano EA, Li F, Stein K, Cartmel B. Health-related quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors: Results from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors—I. Gynecologic Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng Y, Cheng A, Liu X, Feuerstein M. Symptom Profiles, Work Productivity and Quality of Life among Chinese Female Cancer Survivors. Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2016;6 2161-0932.10003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirabeau-Beale KL, Kornblith AB, Penson RT, Lee H, Goodman A, Campos SM, Duska L, Pereira L, Bryan J, Matulonis UA. Comparison of the quality of life of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncology. 2009;114:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng FF, Kalloger SE, Brotto L, McAlpine JN. Determinants of quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors: a pilot study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2014;36:708–715. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Joly F. Ovarian cancer survivors’ quality of life: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avis NE, Levine BJ, Case LD, Naftalis EZ, Van Zee KJ. Trajectories of depressive symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015;24:1789–1795. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical psychology review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stafford L, Foley E, Judd F, Gibson P, Kiropoulos L, Couper J. Mindfulness-based cognitive group therapy for women with breast and gynecologic cancer: A pilot study to determine effectiveness and feasibility. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:3009–3019. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1880-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarroll M, Armbruster S, Frasure H, Gothard M, Gil K, Kavanagh M, Waggoner S, von Gruenigen V. Self-efficacy, quality of life, and weight loss in overweight/obese endometrial cancer survivors (SUCCEED): A randomized controlled trial. Gynecologic Oncology. 2014;132:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yost KJ, Eton DT. Combining distribution-and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences the FACIT Experience. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2005;28:172–191. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2005;28:192–211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganz P, Schag C, Lee J, Sim M-S. The CARES: A generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Quality of Life Research. 1992;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00435432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawighorst-Knapstein S, Schönefußrs G, Hoffmann SO, Knapstein PG. Pelvic exenteration: effects of surgery on quality of life and body image—a prospective longitudinal study. Gynecologic oncology. 1997;66:495–500. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M, Clark MA. Coping and benefit finding among long-term breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Women & Therapy. 2014;37:222–241. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manne S, Schnoll R. Measuring supportive and unsupportive responses during cancer treatment: A factor analytic assessment of the partner responses to cancer inventory. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2001;24:297–321. doi: 10.1023/a:1010667517519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23:16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic medicine. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1989;56:267. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ram N, Grimm KJ. Methods and measures: Growth mixture modeling: A method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:380. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding S, Sanipour F, Moss T. Existence of benefit finding and posttraumatic growth in people treated for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. PeerJ. 2014;2:e256. doi: 10.7717/peerj.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2004;23:595. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Zhu X, Yi J, Tang L, He J, Chen G, Li L, Yang Y. Benefit finding predicts depressive and anxious symptoms in women with breast cancer. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24:2681–2688. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costa RV, Pakenham KI. Associations between benefit finding and adjustment outcomes in thyroid cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:737–744. doi: 10.1002/pon.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portenoy RK. Treatment of cancer pain. The Lancet. 2011;377:2236–2247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Quality of life among long-term (≥5years) colorectal cancer survivors–Systematic review. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46:2879–2888. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tickoo RS, Key RG, Breitbart WS. Cancer-Related Pain. In: Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Butow PN, Jacobsen PB, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle R, editors. Psycho-Oncology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2015. pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]