Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of the study were to: 1) Test the short-term impact of a telephone-delivered cancer parenting education program, the Enhancing Connections-Telephone Program (EC-T), on maternal anxiety, depressed mood, parenting competencies and child behavioral-emotional adjustment and 2) Compare those outcomes with outcomes achieved from an in-person delivery of the same program (EC).

Methods

Thirty-two mothers comprised the sample for the within group design and 77 mothers for the between group design. Mothers were eligible if they had 1 or more dependent children and were recently diagnosed with Stage 0–III breast cancer. Mothers in both groups received 5 intervention sessions at 2-week intervals from a patient educator using a fully scripted intervention manual.

Results

Outcomes from the within-group analysis revealed significant improvements on maternal anxiety, parenting competencies, and the child’s behavioral-emotional functioning. Outcomes from the between-group analysis showed the EC-T did as well or better than EC in positively affecting maternal anxiety, depressed mood, parenting competencies and the child’s behavioral-emotional adjustment. Furthermore, the EC-T had a significantly greater impact than the EC on maternal confidence in helping their family and themselves manage the cancer’s impact and in staying calm during emotionally charged conversations about the breast cancer with their child.

Conclusions

Regardless of the channel of delivery, the Enhancing Connections Program has the potential to positively affect parenting competencies and behavioral-emotional adjustment in mothers and dependent children in the first year of Stage 0–III maternal breast cancer. Its positive impact from telephone delivery holds promise for sustainability.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, parenting education, children, pilot feasibility test

Background and Significance

An estimated 291,130 women were newly diagnosed in 2015 with invasive or in situ breast cancer in the United States [1] and approximately18–22% of those were mothers of minor children [2]. This translates to 52,583 to 64,269 children who were newly impacted by their mother’s breast cancer in the United States.

Patients diagnosed with cancer experience high rates of depressed mood and affective problems for up to or longer than two years after diagnosis [3–5]. Even in the absence of depressed mood, treatment demands or concerns about the cancer can make the parent physically or emotionally unavailable to the child [6–10]. Side effects from polychemotherapy, hormonal therapy, surgery, or radiation treatment can result in months of symptoms, sleep alterations, mood alterations, and extreme fatigue, all of which can impact the child [11].

Although diagnosed mothers want to help their child cope with the breast cancer, they report being too distressed, symptomatic, or pressured to be the attentive and caring parent they want to be [12]. Within this altered home and parenting environment, children are primarily on their own to interpret the cancer and the parents’ changed behavior [13, 14] and an estimated 22–33% of the children will reach or exceed clinical levels of distress [10, 15–17]. Even children scoring in the “normal” range on standardized measures of behavioral-emotional adjustment worry about their family, the ill mother, their future, and try to make sense out of what is happening [18].

In their attempt to make sense of the changes from the cancer, children generate their own images and explanations – often erroneous ones - of the cancer and the majority (81%) worry their mother will die from the breast cancer, even early stage disease [19]. Some children explain the mother’s breast cancer or negative mood by thinking the child caused it or made it worse. Alternatively, the child might misinterpret the parent's physical symptoms as what the child did or said. Such internal attributions are expected to be sources of increased anxiety in the child [20, 21]. To further complicate the situation, children, even children with nightmares and crying spells, hold back disclosing their questions, fears or worries to their ill mother, not wanting to further burden an already distressed parent [22, 23].

Despite the numbers of affected mothers and children and the magnitude of their distress, there are few services and limited printed material to help them manage the toll of the mother’s cancer on the child and the parent-child relationship. Virtually no programs, materials, or services have been rigorously evaluated within a randomized trial with one exception, the Enhancing Connections Program (EC). The EC is a 5-session parent education counseling program that was recently evaluated in a Phase III randomized control trial in 6 states in the U.S. [24]. See Table 1 for a description of the sessions.

Table 1.

Description of EC-T Intervention Sessions & Rationale

|

Session 1: Anchoring yourself to help your child: This session helps the diagnosed mother define the child’s experience with the cancer as distinct from the parent’s own experience and add to the parent’s ways to manage their own cancer-related emotions so that they do not emotionally flood the child. This session positions the mother to be a more attentive listener to the child as well as add to the parent’s self-care skills. Rationale: Diagnosed mothers can attentively listen to their child if they are able to emotionally control their own anxiety. An overly emotive mother is unable to fully attend to her child’s words, maintain healthy interpersonal boundaries, or be emotionally accessible to the child. Overly charged interactions between the mother and child can emotionally flood the child, risking further disconnection with the ill parent. |

|

Session 2: Adding to your listening skills: This session assists the ill mother develop skills to deeply listen and attend to the child’s thoughts and feelings, complementing the parent’s tendency to be a teacher, not a deep listener, of the child’s concerns, worries or understandings. Rationale: In the absence of intervention, diagnosed mothers function like biology teachers, offering the child biomedical facts about the cancer using highly charged information that is not developmentally appropriate. By focusing on the child’s view of the cancer, the ill mother is more informed and able to strategically support the child in ways that articulate with the child’s views and concerns. |

|

Session 3: Building on your listening skills: This session builds on Session 2 and adds to the mother’s abilities to elicit and assist the child elaborate the child’s concerns or feelings, even a reticent child. It is one thing to engage a talkative child; it is another to help a child talk who is withdrawn. Rationale: Session 2 equips the ill mother with additional communication and parenting skills that enable her initiate difficult cancer-related conversations and also interact with an upset child or one who is not forthcoming. |

|

Session 4: Being a detective of your child’s coping: This session helps the diagnosed mother focus on and non-judgmentally interpret the child’s ways of coping with the cancer. It includes exercises that assist the mother to relinquish negative assumptions about the child’s behavior related to the mother’s cancer. By giving away negative assumptions, the session enables the ill parent to positively interpret, not negatively evaluate, her child’s behavior. Concurrently, the session offers the ill parent ways to elicit ways to assist the child cope with the cancer-related pressures. Rationale: Listening and drawing out the child’s concerns is one thing; engaging in interpersonal behavior that the child finds supportive is a different skill. Both skills are important for the parent to use to reduce the child’s cancer-related concerns and distress. |

|

Session 5. Celebrating your success: This session focuses on the gains the ill mother made in prior sessions and what she accomplished, in her own words, in parenting their child about the cancer. Both self-monitoring and self-reflection are key elements to enhance the parent’s self- efficacy in supporting and communicating with her their child; this session structures specific self- reflective exercises to help the parent internalize their accomplishments into a new self-view as an efficacious parent. The session also assists the ill parent to identify available resources that can be used after program completion to maintain the parent’s newly acquired gains from the program. Rationale: This final session helps the parent internalize a new view of the self as a skilled and confident parent. Through the ill parent’s self-report of her own behavior and the gains she attributes to themselves, the session anchors the parent’s new identity as an efficacious parent, not just a parent with new skills. |

Results from the randomized trial of the EC Program were remarkable. Compared to controls, mothers in the experimental group improved on depressed mood, parenting skills, anxiety, parenting quality, and parenting confidence. Compared to controls, experimental children improved on behavioral-emotional adjustment: total behavior problems and externalizing problems significantly declined, anxiety/depressed mood significantly declined, and internalizing problems tended to decline. At 1 year, experimental children remained significantly less depressed than controls on both mother- and child-reported measures [24].

But the efficacy of the EC Program was tested as an in-person, at home-delivered program that often involved hours of travel from the study center to patients’ homes. What was still needed was an EC Program that could be sustained and easily accessed. The EC-telephone delivered (EC-T) Program, to be evaluated in the current study, was developed in response to these goals and consisted of the same content and format of the original EC Program.

Study Protocol

Study participants in the EC-T Program were recruited from the medical practices of surgeons, radiologists, and medical oncologists from cities in the east and west coast. Study participants were eligible if they were recently diagnosed with early stage (local or regional, Stage 0–III) breast cancer, read and wrote English as one of their languages of choice, and had a child 5–12 years of age who had been told their mother’s diagnosis. A recent diagnosis meant the diagnosis was within 7 months, a period of time of active treatment and early recovery from the cancer.

After approval by the Human Subjects Committee at the study center and recruitment sites, eligible study participants were recruited through 3 channels: a recruitment letter mailed by site intermediaries, provider referral, or self-referral. When mothers verbally agreed to participate, they were mailed a study packet containing a consent form; baseline and post-intervention questionnaires; and all program materials [each intervention session was sealed in a separate envelope]. The patient educator contacted the mother following the mother’s receipt of the packet to assist in interpreting the consent form and to answer questions about the study questionnaires. Once the signed consent form and baseline questionnaires were received, the patient educator scheduled the first telephone intervention session. Five intervention sessions (lasting 30 – 60 minutes each) were scheduled at 2-week intervals. At immediate completion of the 5th session, the mother was asked to complete and return the post-intervention questionnaires in a provided stamped, addressed envelope. Questionnaires were received by the study team an average of 2.69 weeks after completing Session 5.

Initial training of the patient educators set the standards for program delivery. Intervention fidelity and dosage were monitored by comparing digital recordings of the intervention sessions against standardized performance checklists. Weekly meetings with the patient educators were held to review their performance and field experiences in delivering the intervention.

Theoretical Rationale & Components of Intervention

The EC-T Program derived from three theories: a developmental-contextual model of parenting [25–27]; the transactional model of coping [4, 5]; and Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory [28, 29]. The first two theories influenced the content of the intervention sessions, including ways to communicate with the child in developmentally appropriate language and staying within the child’s perspective. Social Cognitive Theory, the third theory, provided the structure for each intervention session, including the in-session and at-home assignments that engaged the diagnosed mother in skill and efficacy-enhancing exercises. These assignments included ways to remain emotionally and behaviorally accessible to her child, even during particularly challenging conversations caused by the cancer, e.g., “Mommy, are you going to die from the cancer?”

Study Measures

Standardized questionnaires with well established validity and reliability were used to assess the impact of the EC-T. Respondent burden was well tolerated and instruments were non-sensitizing, reflected in the completion and return rate of study questionnaires. All measures were the same as those used to assess efficacy in the randomized trial of the EC; psychometric details were reported earlier [24].

Depressed mood

Maternal depressed mood was measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [30–33]. Internal consistency reliability in the EC trial was 0.90.

Anxiety

Maternal anxiety was measured by the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [34]. Internal consistency reliability for the EC study sample was 0.96.

Parenting self-efficacy

Maternal self-efficacy was measured by three subscales of the self-reported Cancer Self-Efficacy Scale (CASE): Help Child, Deal & Manage, & Stay Calm subscales [8]. The Help Child subscale (9 items) measured the mother’s confidence in being able to talk with her child about the child’s cancer-related concerns; e.g., “I can assist my child to talk out his/her worries about my cancer.” The Deal and Manage subscale (13 items) measured the mother’s confidence in helping herself and her family cope with the challenges of the cancer, e.g.,“I am able to take care of my family even as I experience pressures from the cancer.” The Stay Calm subscale (6 items) measured the mother’s confidence in being able to stay calm during difficult or highly charged conversations with her child about the cancer. The internal consistency reliabilities in the EC clinical trial were: 0.97 for Help Child, 0.96 for Deal and Manage, and 0.96 for Stay Calm subscales.

Parenting quality

Parenting quality was measured by 6 items on the Family-Peer Relationship Scale (FPRQ), the mother’s report of the type of interpersonal communication she has with her child [35]. The two subscales were Disclosure of Negative Feelings, e.g., “How likely is it that the child will share if s/he is feeling mad or angry?” and Disclosure of Bad Things Happening, e.g., “How likely is it that the child will share if something bad happens to the child. The internal consistency reliabilities were 0.89 and 0.86, respectively, in the EC clinical trial.

Parenting skills

The mother’s parenting skills were measured by the 14-item mother-reported Parenting Skills Checklist that described the interactional behaviors mothers used to assist their child disclose, discuss, and cope with the breast cancer. The measure was developed by the study team to describe observable behaviors mothers could use to communicate and support their child about the breast cancer. The developmental-contextual model of parenting was the conceptual basis for the measure [25,26]. The checklist consists of two subscales, the Elicitation subscale, e.g., “I draw out my child’s concerns about the breast cancer,” and the Connecting and Coping subscale, e.g., “I set up private times to talk to my child about the breast cancer.” The measure’s internal consistency reliability and concurrent and construct validity were assessed in the original randomized trial. The internal consistency reliabilities for the Elicitation and the Connecting and Coping subscales were 0.74 and 0.90, respectively [24]. The Elicitation subscale positively correlated with the mother’s confidence in being able to help her child (r=.519; p<.0001) and with her confidence in being able to help the child cope with the impact of the cancer (r=.22, p<.0001). Both subscales were inversely related to the mothers’ anxiety; the more anxious the mother, the lower her scores on her elicitation skills (r= −.148, p=.05) and the lower her scores on her connecting and coping skills (r= −.212, p<.005).

Child behavioral-emotional adjustment

The child’s behavioral-emotional adjustment was measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a mother-reported scale of a broad range of behavior problems in children ages 6–18 [36]. Response options range from 0 to 2 from “Not True (as far as you know)” to “Somewhat or Sometimes True” to “Very True or Often True.” The Externalizing score measures a child’s aggressive, antisocial, and under-controlled behavior; the Internalizing score measures the child’s fearful, inhibited, and over-controlled behavior. The internal consistency reliabilities for the EC clinical trial were 0.97 for Total Behavior Problems, 0.90 for the Internalizing score, and 0.94 for the Externalizing score. For the current study, we used the CBCL form for 4–18 year olds and its computer software that calculates the same Internal, External and Total CBCL scores as the version for 6–18 year olds that was used in the prior clinical trial.

Study Design

The short-term impact of the EC-T was evaluated using both a within-and between-subjects design. The within-subjects design compared the pre-with post-intervention scores for the EC-T study sample. The between-subjects design compared outcomes from the EC-T with outcomes from the intervention arm of the EC clinical trial. In the within-subjects design, we hypothesized that outcomes would improve on all measures, compared to baseline. Two-tailed tests of significance were calculated using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test. In the between-subjects design, we hypothesized that outcomes on the EC-T would be comparable to those obtained from the EC. Linear Mixed Models was used to test the between-group differences and is based on Maximum Likelihood Estimation in which an iterative method estimates a trajectory for each study participant based on all available data for that participant supplemented by data obtained from the total sample [37, 38]. This estimation method has two advantages over traditional analysis of variance models: all available data are used from all participants rather than dropping participants with missing data. Second, it incorporates serial correlations among observations over time, thereby reducing bias. Effect sizes were calculated for all comparisons.

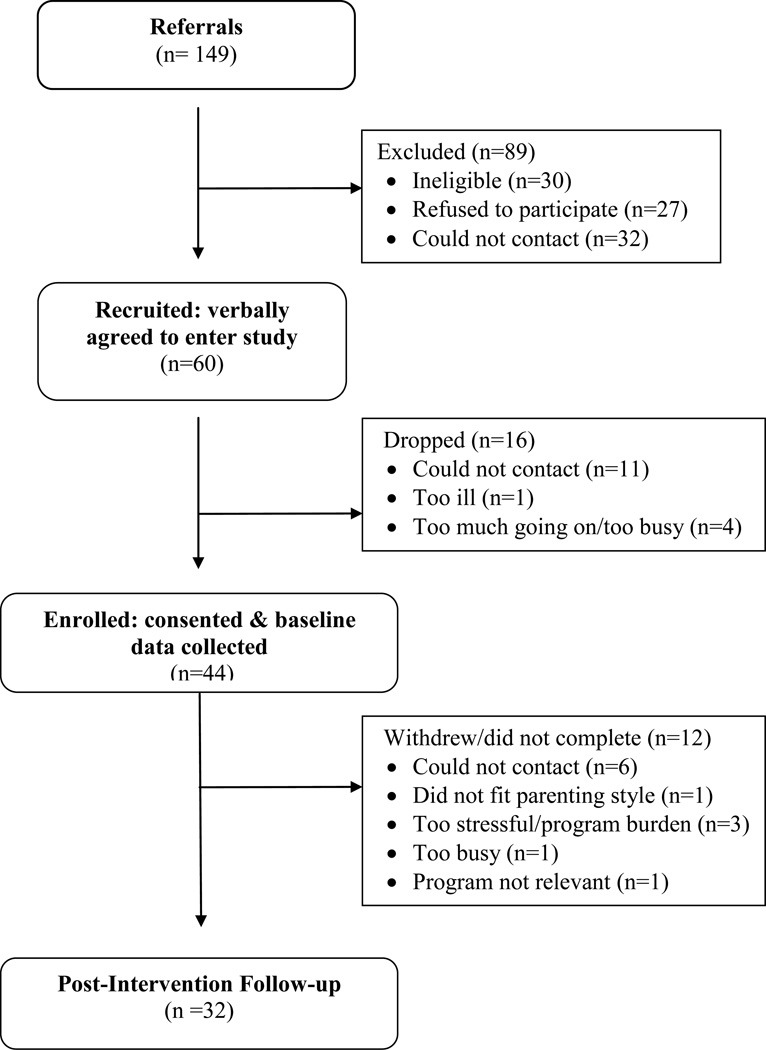

Results from Within-Subjects Design

A total of 149 referrals were made to the study, of which 44 were enrolled; see Figure 1. Eligible mothers declined participation during recruitment because they did not need or want the program, stating that their children were doing fine now or that participating in the study was not how they wanted to spend their time (n=24); were too busy with child care or treatment demands to add one more thing to their schedules (n=8); or spouses felt the program was not a good use of the families’ time (n=2). Five potential participants refused enrollment but did not provide a specific reason. Of the 44 mothers who enrolled, 32 mother-child dyads completed post-intervention measures. These 32 mothers and their 32 school age children constituted the study sample for analysis: 17 male and 15 female children.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Study Participants for EC-T Participants with Breast Cancer

The 12 mothers who completed baseline data but dropped from the study (Figure 1) were compared on baseline measures from the retained sample on demographic, treatment data, and on scores on the CES-D, STAI, and the CBCL. Mothers and children who dropped were comparable to the retained sample at baseline except they had fewer children, lower state anxiety, and higher confidence in their ability to stay calm in interacting with their child about the breast cancer.

The majority of diagnosed mothers (79.4 %) was within 5 months of diagnosis; averaged 42.6 years of age (SD 4.8); and were White (81%). An additional 19% were African American, Filipino, Hispanic or Asian. Most mothers (53.1%, n=17) were surgically treated with breast conserving surgery for their cancer and 78.1% (n=25) were on adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or radiation therapy) at time of study participation.

The study sample was educated and middle class; incomes ranged from $20,000 to over $150,000 with the majority of households reporting incomes over $75,000. All but one of the diagnosed mothers was married; the average length of marriage was 16.7 years (SD 5.6). Their spouse/partners averaged 45.9 years (SD 8.2) of age. Half of the diagnosed mothers (50%) worked outside the home at least 20 or more hours per week during participation in the study. Some mothers (34.4%) were on medical leave from employment and 15.6% reported they did not work outside the home.

The majority of families (84.4%) had two or more children in the household, ranging in age from 5 to 12, 46.9% of whom were females. The referent child with whom the diagnosed mother completed the at-home assignments averaged 8.2 years (SD 2.4).

Analyses proceeded in two phases for the within-subjects design. First, pre-posttest outcomes were compared for the total study sample; see Table 2. Second, results were examined for the subsample of mothers whose baseline scores were in the clinically distressed range on depressed mood (CES-D ≥ 16) and on anxiety (STAI score of 40 or higher).

Table 2.

Results from Within Group Analysis of Mothers’ & Children’s Outcomes in EC-T

| n=32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median | p* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s Depressed Mood & Anxiety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maternal Depressed Mood | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 17.34 (9.85) | 17.00 | .009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 12.43 (6.34) | 12.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maternal Anxiety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 43.78 (12.74) | 42.00 | .004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 35.97 (9.80) | 35.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parenting Self-efficacy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Help Child Subscale | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 61.47 (15.34) | 62.50 | <.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 78.66 (7.93) | 79.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deal & Manage Subscale | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 95.81 (18.62) | 99.50 | <.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 110.89 (12.72) | 112.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stay Calm Subscale | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 47.28 (8.02) | 48.50 | <.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 54.16 (4.57) | 54.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parenting Quality | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disclosure of Negative Feelings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 13.94 (3.08) | 14.00 | .990 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 13.91 (3.32) | 14.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disclosure of Bad Things Happening | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 11.50 (2.36) | 12.00 | .205 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 11.13 (2.08) | 11.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s Parenting Skills | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elicitation Skills | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 7.00 (2.18) | 8.00 | .002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 7.91 (1.30) | 8.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connecting & Coping Skills | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 18.38 (6.20) | 18.00 | <.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 23.81 (3.41) | 24.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Child’s Behavioral-Emotional Adjust. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Problem T-score | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 50.19 (9.64) | 50.50 | .019 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 46.78 (9.66) | 46.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internalizing T-score | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 51.09 (9.31) | 49.50 | .011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 47.16 (9.13) | 47.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Externalizing T-score | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | 49.81 (11.66) | 48.50 | .042 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-test | 48.28 (9.84) | 48.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test; 2-tailed test

Results for the total sample revealed significant improvements between pre-posttest scores on 6 of the 9 outcome measures. Details follow.

Maternal depressed mood and anxiety

Maternal depressed mood did not significantly change but showed a statistical tendency to improve (Wilcoxon Signed Rank, 2-tailed test, p=.09). However, maternal anxiety did significantly improve between baseline and post-intervention (Wilcoxon Signed Rank, 2-tailed test, p= .004).

Parenting skills and parenting self-efficacy

Parenting competencies improved on both parenting skills and parenting self-efficacy. Parenting skills significantly improved in mothers’ abilities to elicit their child’s concerns, worries or questions about the mother’s cancer (p=.002) and mothers gained new ways to help their child cope and manage the mother’s cancer (p<.001).

Mothers’ self-efficacy significantly improved in their ability to stay calm while talking with their child about the breast cancer (p<.001); in helping their family and themselves manage the impact of the cancer (p<.001); and in assisting their child better manage the toll of the mother’s breast cancer (p<.001).

Parenting quality

Parenting quality did not significantly change but remained stable between pre- and posttest scores.

Child’s behavioral-emotional adjustment

The child’s behavioral-emotional functioning significantly improved on the Total, Internalizing, and Externalizing scores of the Child Behavior Checklist. More specifically, the child’s withdrawn (Internalizing) and anti-social behavior (Externalizing) were significantly reduced (p=.011 and p=.042, respectively). The total number of behavioral problems was also significantly reduced (p=.019).

Outcomes for the subsample of distressed mothers were next examined. Fifteen of the 18 mothers (15/18; 83%) who scored in the clinical range on depressed mood at baseline improved at posttest. Of those who improved, 11/15 (61%) moved from the clinical to the normal range. However, 4/15 (27%) of mothers who were depressed at baseline (CES-D ≥16) and improved at posttest still remained in the clinical range post-intervention. Thirty-nine percent (7/18) of mothers who were depressed at baseline either did not improve or did not move into the normal range on the CES-D at exit from the intervention.

Eleven of the 18 mothers (11/18; 61%) who scored in the clinical range at baseline on anxiety (STAI ≥ 40) moved into the normal range at post-intervention. However, 7 (7/18; 39%) mothers with clinically elevated anxiety at baseline did not improve at posttest.

Results from the Between-Subjects Design

Results from the between-subjects design revealed that the EC-T did as well or better in positively affecting maternal and child outcomes than did the EC. See Table 3. Outcomes from the EC-T were comparable to outcomes from the EC on maternal anxiety; maternal depressed mood; parenting self-efficacy in helping the child; both sub-scales of the parenting skills questionnaire; and on the child’s behavioral-emotional adjustment, including the Total, Internalizing, and Externalizing scores of the CBCL. Furthermore, the EC-T had a significantly greater impact than the EC on two of the three subscales of self-efficacy. Specifically, mothers in the EC-T were significantly more confident than mothers in the EC in helping their family and themselves deal with and manage the cancer’s impact (d=0.42; Beta= −7.51, p=.028) and in staying calm when talking with their child, even during emotionally charged conversations about the breast cancer (d=0.42; Beta= −3.64, p=.034).

Table 3.

Linear Mixed Model Analysis Comparing Outcomes from EC-T (n=32) and EC (n=77)

| Baseline | 2 months post- baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Measures | EC-T Mean (SE) |

EC-T Mean (SE) |

EC-T Mean (SE) |

EC-T Mean (SE) |

Effect Size d |

Beta (β)a | p-valueb | |

| Maternal Anxiety | 44.47 (1.99) | 33.97 (1.25) | 35.91 (1.99) | 29.85 (1.25) | 0.31 | 4.44 | .089 | |

|

Maternal Depressed Mood |

17.15 (1.53) | 12.95 (0.96) | 11.81 (1.53) | 9.11 (0.95) | .10 | 1.50 | .435 | |

| Parenting Self-efficacy | ||||||||

| Help child subscale | 60.71 (2.41) | 73.19 (1.50) | 78.68 (2.41) | 86.31 (1.50) | .26 | −4.85 | .132 | |

| Deal and manage subscale | 95.58 (2.94) | 111.56 (1.83) | 111.14 (2.94) | 119.62 (1.83) | .42 | −7.51 | .028 | |

| Stay calm subscale | 47.09 (1.26) | 49.71 (0.79) | 54.16 (1.26) | 53.15 (0.79) | .42 | −3.64 | .034 | |

| Parenting Quality | ||||||||

| Disclosure of Negative Feelings | 13.76 (0.60) | 14.36 (0.37) | 13.76 (0.06) | 15.00 (0.37) | .25 | 0.64 | .277 | |

| Disclosure of Bad Things Happening | 11.54 (0.38) | 12.47 (0.23) | 11.04 (0.38) | 12.85 (0.23) | .39 | 0.88 | .033 | |

| Parenting Skills | ||||||||

| Elicitation skills | 6.92 (0.27) | 7.22 (0.17) | 7.85 (0.27) | 8.38 (0.17) | .14 | 0.22 | .538 | |

| Connecting & Coping | 18.20 (0.88) | 19.85 (0.55) | 23.53 (0.88) | 23.80 (0.55) | .29 | −1.38 | .211 | |

| Child’s Behavior Checklist | ||||||||

| Total T-score | 50.69 (1.82) | 48.28 (1.13) | 46.86 (1.82) | 43.50 (1.13) | .03 | 0.53 | .494 | |

| External T-score | 50.37 (1.71) | 46.48 (1.07) | 48.27 (1.71) | 43.43 (1.09) | .26 | −0.95 | .450 | |

| Internal T-score | 51.81 (1.72) | 50.66 (1.07) | 47.47 (1.72) | 46.85 (1.07) | .21 | −0.94 | .753 | |

Beta (β) – Interaction Term (Study × Time): baseline versus 2-months post-baseline

p-value: significance of Interaction Term

Only one outcome showed significantly greater improvement in the EC compared to the EC-T. Namely, the EC had a significantly greater impact on the child’s disclosure of bad things happening than did the EC-T (d=.39; Beta=0.88, p=.033).

Gains Attributed by Mothers to Participation in EC-T

In addition to examining outcomes on standardized questionnaires, mothers were interviewed at 1 month after exiting the EC-T Program by a specially trained phone worker who was masked on the content of the program. Mothers were asked, “Thinking back on the program overall, what part, if any, was most helpful for you?” “What, if anything, have you learned about helping your child from this program?” Each interview was digitally audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, verified for transcription accuracy, and content analyzed using inductive coding methods adapted from grounded field theory [39]. Trustworthiness of study results was protected by maintaining an audit trail; coding to consensus using constant comparative analysis; and carrying out formal peer debriefing throughout coding.

Mothers reported they learned how to listen to and help their child express their thoughts and feelings, including not blocking nor shutting the child down. Mothers said their greatest gains were in acquiring and practicing new ways to communicate with their child to help the child open up, including asking open-ended questions and initiating and sustaining two-way conversations. Mothers also said they gained new ways to stay calm when talking to their child and to distinguish their personal feelings from their child’s feelings. Mothers reported they also learned ways to communicate with their child that did not require the mother to teach, problem solve, or fix anything.

Discussion of Results

The EC-T Program resulted in improved behavioral-emotional functioning in both the diagnosed mothers and their school age children; outcomes reached or exceeded comparable results as the in-person delivered EC Program. Overall, results suggest that a brief, fully scripted cancer parent education program delivered by telephone has the potential to enhance mother and child functioning during the early treatment phase of the mother’s breast cancer.

Results from the clinically distressed mothers in the EC-T sample on the CES-D and STAI were also remarkable. Of note, 61% of women with clinically elevated depressed mood and clinically elevated anxiety scored in the normal range at exit from the intervention. Our results compare favorably to completed studies of psychosocial interventions that were designed to improve overall mood and depression in cancer patients [3]. However, recall that 39% of depressed and anxious mothers did not substantially improve following EC-T. It is beyond our data to know why some distressed mothers improved while others did not. Additional research is needed to identify predictive factors that distinguish between distressed mothers with potential to improve and those not likely to improve.

Only one outcome measure failed to significantly improve in both the within- and between-subjects design: parenting quality. A more sensitive measure of parenting quality related to parental illness is needed in future studies.

The comparability of outcomes between the EC-T and EC is positive news. The EC-T was able to reach a more highly distressed sample of recently diagnosed mothers than did the EC; did not require travel; was accessible to mothers for whom travel might pose a burden; and did not compete for clinic space. Results across both the within-subjects and between-subjects analyses provide strong evidence that the impact of EC is not dependent on the channel through which it is delivered.

Future research needs to consider developing the EC program as a web-based program. Recall that 43% (n= 26) of the women who initially agreed to enter the study (n= 60) were later unable to be contacted, were too ill, or were too busy to participate (Figure 1). Web-based programs, like the telephone delivered program tested in the current study, offer accessibility and would allow newly diagnosed mothers access to the program on their own time and around episodes of symptoms or treatment demands. Child-rearing mothers are also likely to be among internet users; 97% of Americans aged 18–29 and 93% of those aged 30–49 use the Internet (PEW, 2014). However, we do not want to be overly enthusiastic about endorsing a web-based delivery. A web-based intervention might add to mothers’ anxiety or frustrate them if internet connectivity was slow, unpredictable, or the technology caused mothers to make mistakes.

Study Limitations & Research Implications

Study results should be viewed with both caution and optimism. The use of a single group (within-subjects) design prevents unconditionally attributing the short-term impact of EC-T to observed outcomes. In addition, Type I error was likely inflated, given the small sample size and the number of pre-posttest comparisons that were computed. Study results are also limited to mothers and children comparable to those in the EC-T and do not generalize to fiscally or educationally challenged families, or to non-English speaking or Stage IV populations. All of these groups warrant further attention. Further, child-rearing young adult survivors with other than breast cancer are also likely to have dependent children but tend of be overlooked. Future studies are needed to test the impact of the EC-T with parents of either gender with other types of cancer, not just breast cancer. EC-T is relevant to all types of cancers during initial treatment for non-metastatic disease.

Optimism is also in order. When results from the within-subjects design are triangulated with those from the between subjects design and mothers’ exit interviews, evidence suggests that the EC-T, not some alternative source, produced the observed changes. That such a program can be offered by telephone (cell phone or land line) protects access and reach for ill mothers who might otherwise be underserved. Further evaluation of the EC-T within a more rigorous research design is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, NIH under award numbers R03 CA 178 488 and R01 CA 78 424. The content of the manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of [alphabetical], Tessa Floyd, Jonika Hash, Alicia M. Korkowski, Victor L. Martin & Weichao Yuwen. The authors dedicate this paper to the families who participated in this study, our greatest teachers.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial relationship with the funding organization that sponsored the research. The senior author has full control of all the primary data and agrees to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. [Accessed January 21, 2016];Cancer facts and figures 2015. Atlanta, GA. 2015 http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/allcancerfactsfigures/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Alfano CM, McNeel TS. Parental cancer and the family: A population-based estimate of the number of US cancer survivors residing with their minor children. Cancer. 2010;116(18):4395–401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, Cowley D, Pepping M, McGregor BA, Gralow J. Major depression after breast cancer: A review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(2):112–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compas BE, Worsham NL, Epping-Jordan JE, Grant KE, Mireault G, Howell DC, Malcarne VL. When mom or dad has cancer: Markers of psychological distress in cancer patients, spouses, and children. Health Psychol. 1994;13(6):507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compas BE, Worsham NL, Ey S, Howell DC. When mom or dad has cancer: II. Coping, cognitive appraisals, and psychological distress in children of cancer patients. Health Psychol. 1996;15(3):167–175. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RT, Fuemmeler B, Anderson D, Jamieson S, Simonian S, Hall RK, Brescia F. Adjustment of children and their mothers with breast cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(3):297–308. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigal JJ, Perry JC, Robbins JM, Gagne MA, Nassif E. Maternal preoccupation and parenting as predictors of emotional and behavioral problems in children of women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1155–1160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis FM. Therapy for Parental Cancer and Dependent Children. In: Watson M, Kissane D, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy in Cancer Care. NY: Wiley; 2011. pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannatta K, Ramsey RR, Noll RB, Gerhardt CA. Associations of child adjustment with parent and family functioning: Comparison of families of women with and without breast cancer. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(1):9–16. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c82a44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson M, St James-Roberts I, Ashley S, et al. Factors associated with emotional and behavioural problems among school age children of breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauch PK, Muriel AC. The importance of parenting concerns among patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behar L, Lewis FM. Single Parents Coping With Cancer and Children in. In: Christ G, Messner C, Behar L, editors. Handbook of Oncology Social Work. NY: Oxford University Pres; 2015. pp. 429–441. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issel LM, Ersek M, Lewis FM. How children cope with mother's breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1990;17(3 Suppl):5–12. discussion 12-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zahlis EH, Lewis FM. Mother’s story of the school-age child’s experience with the mother’s breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1999;16(2):25–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huizinga GA, van der Graaf WT, Visser A, Dijkstra JS, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Psychosocial consequences for children of a parent with cancer: A pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(3):195–202. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson E, While D. Children's adjustment during the first year of a parent's cancer diagnosis. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2002;20(1):15–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser A, Huizinga GA, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Emotional and behavioural functioning of children of a parent diagnosed with cancer: A cross-informant perspective. Psycho oncology. 2005;14(9):746–758. doi: 10.1002/pon.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatraman S, Lewis FM. Preliminary testing of a standardized, self-report measure of children’s attributed cancer-related concerns. New Orleans, LA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zahlis EH. The child's worries about the mother's breast cancer: Sources of distress in school-age children. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(6):1019–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armsden GC, Lewis FM. The child's adaptation to parental medical illness: Theory and clinical implications. Patient Educ Couns. 1993;22(3):153–165. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(93)90095-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armsden GC, Lewis FM. Behavioral adjustment and self-esteem of school-age children of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis FM. The family’s “stuck points” in adjusting to cancer. In: Holland JC, et al., editors. Psycho-Oncology. Oxford : NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 511–515. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis FM, Behar LC, Anderson KH, Shands ME, Zahlis EH, Darby E, Sinsheimer JA. Blowing away the myths about the child’s experience with the mother’s breast cancer. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, De-Nour AK, editors. Cancer and the Family. NY: John Wiley; 2000. pp. 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis FM, Brandt PA, Cochrane BB, et al. The Enhancing Connections Program: A six-state randomized clinical trial of a cancer parenting program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):12–23. doi: 10.1037/a0038219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins WA, Harris M, Susman A. Parenting during middle childhood. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Volume 1: Children and parenting. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins WA, Laursen B. Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner RM, Castellino D, Terry P, Villarruel F, McKinney M. Developmental contextual perspective on parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Volume 2: Biology and Ecology of Parenting. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conerly RC, Baker F, Dye J, Douglas CY, Zabora J. Measuring depression in African American cancer survivors: The reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Study--Depression (CES-D) Scale. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(1):107–114. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Given C, Given B, Rahbar M, et al. Does a symptom management intervention affect depression among cancer patients: Results from a clinical trial. Psycho-oncology. 2004;13(11):818–830. doi: 10.1002/pon.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(5):437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Marsh BJ. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults. Mahwah, N: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 993–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellison ES. A multidimensional, dual-perspective index of parental support. West J Nurs Res. 1985;7(4):401–424. doi: 10.1177/019394598500700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear mixed models: A practical guide using statistical software. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Leeuw J, Meijer E. Introduction to Multilevel Analysis. In: De Leeuw J, Meijer E, editors. Handbook of Multilevel Analysis. NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis FM, Deal LW. Balancing our lives: A study of the married couple's experience with breast cancer recurrence. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(6):943–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]