Abstract

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Current avenues of AD research focus on pre-symptomatic biomarkers that will assist with early diagnosis of AD. The majority of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) based biomarker research to date has focused on neuronal loss in grey matter and there is a paucity of research on white matter.

Methods

Longitudinal DTI data from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 database were used to examine 1) the within-group microstructural white matter changes in individuals with AD and healthy controls at baseline and year one; and 2) the between-group microstructural differences in individuals with AD and healthy controls at both time points.

Results

1) Within-group: longitudinal Tract-Based Spatial Statistics revealed that individuals with AD and healthy controls both had widespread reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) and increased mean diffusivity (MD) with changes in the hippocampal cingulum exclusive to the AD group. 2) Between-group: relative to healthy controls, individuals with AD had lower FA and higher MD in the hippocampal cingulum, as well as the corpus callosum, internal and external capsule; corona radiata; posterior thalamic radiation; superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus; fronto-occipital fasciculus; cingulate gyri; fornix; uncinate fasciculus; and tapetum.

Conclusion

The current results indicate that sensitivity to white matter microstructure is a promising avenue for AD biomarker research. Additional longitudinal studies on both white and grey matter are warranted to further evaluate potential clinical utility.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADNI, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; FSL, Functional MRI of the Brain Software Library; HC, healthy controls; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MD, mean diffusivity; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MMSE, Mini Mental Status Exam; ROI, region of interest; TBSS, Tract-Based Spatial Statistics; WMS, Wechsler Memory Scale

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Aging, Diffusion tensor imaging, Magnetic resonance imaging, White matter

Highlights

-

•

Longitudinal white matter research in Alzheimer's disease.

-

•

Diffusion tensor imaging used to assess microstructural white matter changes.

-

•

Decreased fractional anisotropy and increased mean diffusivity over one year.

-

•

Widespread changes in Alzheimer's disease include the hippocampal cingulum.

-

•

DTI holds potential as Alzheimer's disease biomarker.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Pathologically, AD is characterized by extracellular aggregation of amyloid-beta into senile plaques and hyper-phosphorylated tau protein accumulation in intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles (Beach et al., 2012). Clinically, AD is characterized by progressive cognitive decline that typically presents with memory loss as the initial and primary concern (Alzheimer's Association, 2014). Worldwide, approximately 47.5 million individuals are living with dementia, the majority of which suffer from Alzheimer's disease (World Health Organization, 2016).

Emerging research has focused on the identification of biomarkers that will assist with early diagnosis of AD and allow for the evaluation of potential disease modifying treatments (Dubois et al., 2010). Considerable effort has been devoted to the development of PET molecular neuroimaging biomarkers of amyloid and tau in AD (e.g. Wang et al., 2016), however, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) continues to offer a non-invasive and easily repeatable method of examining neuropathological changes associated with AD. To date, the majority of MRI-based research in AD has focused on tissue loss in grey matter structures (Cash et al., 2014). These findings indicate widespread whole brain grey matter atrophy in individuals with AD, including enlarged ventricles and decreased hippocampal volume (Gold, 2012, Hampel et al., 2014, Perl, 2010, Teipel et al., 2010). In terms of white matter changes, the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis (Hardy and Higgins, 1992) suggests that axonal degeneration arises as a result of Wallerian degeneration. However, the close association of tau with both axonal integrity and with the cognitive symptoms of AD suggests that white matter changes may occur independently and perhaps prior to changes in grey matter. Furthermore, the retrogenesis model proposed by Bartzokis et al. (2007) hypothesizes that white matter degeneration in AD follows a reverse pattern to that observed in early myelination. These ideas lend support to the notion of white matter changes in AD as biomarkers that may be particularly helpful in earlier identification of AD (see Amlien and Fjell, 2014 for a review).

One promising tool to detect early white matter alterations in the brain is diffusion tensor imaging (DTI; Alexander et al., 2007, Soares et al., 2013). Currently, fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) are the most frequently reported DTI metrics (Amlien and Fjell, 2014). FA is a measure of the degree of directionality of water diffusion, thought to be driven by microstructure such as cellular boundaries and myelin (Alexander et al., 2007, Amlien and Fjell, 2014, Soares et al., 2013), while MD is a measure of the mean water diffusion rate (Soares et al., 2013). These metrics can provide information regarding changes or differences in restriction to diffusion that may reflect myelination and axonal integrity. Specifically, decreases in FA and increases in MD are indicative of decreased myelination and loss of axons, as a consequence of neurodegeneration (Bosch et al., 2012, Kantarci, 2014, Serra et al., 2010).

The majority of published AD research has used a cross sectional design and consistently revealed low FA and high MD in widespread white matter regions including the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (including hippocampal regions), as well as the corpus callosum and longitudinal association tracts (Acosta-Cabronero and Nestor, 2014, Sexton et al., 2011, Stebbins and Murphy, 2009, Stoub et al., 2014). Microstructural water diffusion changes are not unique to AD, however. In fact, some of these changes occur during the healthy aging process. For example, Burzynska et al. (2010) examined DTI indices from young and older adults and found an age-related reduction in FA within a number of white matter structures. These findings are consistent with recent reviews that discuss degeneration of white matter tracts with age, which may result from cerebrovascular changes or other common underlying health conditions (e.g. Lockhart and Decarli, 2014).

Recent studies that have utilized a longitudinal design to investigate microstructural changes in AD via DTI have revealed decreased FA in the uncinate fasciculus (Kitamura et al., 2013) as well as FA and MD changes in the fornix, corpus callosum, and inferior cingulum, over time in individuals with AD (Genc et al., 2016, Norwrangi et al., 2013).

The current study is the first to use the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database to investigate changes in diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics over time. The ADNI database has collected and made available DTI data from individuals with AD and healthy controls at multiple sites across North America. The overarching aim of the current study was to determine if DTI, as a measure of microstructural white matter integrity, has potential as a biomarker of AD. The study had two specific objectives: 1) to examine within-group microstructural white matter changes in individuals with AD and healthy controls at baseline and year one; and 2) to evaluate between-group differences in individuals with AD and healthy controls at both time points. It was hypothesized that 1) individuals with AD would have decreased FA and increased MD across time and that 2) individuals with AD would have lower FA and higher MD as compared to healthy controls at both time points. A whole brain exploratory approach was taken to capture differences between groups in any region, however, it was predicted that medial temporal regions would be more greatly affected in AD, compared to healthy controls, given that this is one of the first affected regions in the progression of AD grey matter pathology (Braak and Braak, 1991, Gold, 2012, Hampel et al., 2014, Perl, 2010, Teipel et al., 2010).

2. Method and materials

All data were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 (ADNI2) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI, led by Principal Investigator Dr. Michael W. Weiner, was launched in 2003 with the goal of testing whether longitudinal brain imaging, biological markers, and neuropsychological assessment can be used together to measure the progression of AD. For more information, please see www.adni-info.org.

2.1. Participants

Full eligibility criteria for the ADNI are described in the ADNI2 procedures manual (Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2008). Briefly, individuals with AD met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984), demonstrated abnormal memory function on the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) II (≤ 8 for 16 years education and above), had a MMSE score between 20 and 26, and had a Clinical Dementia Rating of 0.5 (very mild) or 1.0 (mild). Healthy controls were required to be free of subjective memory concerns, to have a score within the normal range on the WMS Logical Memory II (≥ 9 for 16 years of education and above), have a MMSE score between 24 and 30, and a Clinical Dementia Rating of 0 (none).

Individuals from the ADNI database were included in the present study if data was available at both baseline and year one. Data were retrieved from 34 individuals with AD (mean age = 75.8 ± 7.6; 10 females; MMSE = 23.59 ± 1.74; Logical Memory II = 1.65 ± 1.94) and 33 healthy age-matched controls (mean age = 73.0 ± 6.6; 16 females; MMSE = 29.03 ± 1.26, Logical Memory II = 11.70 ± 2.84). There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to age, gender, or education (Table 1). The mean number of days from baseline to year one was not significantly different between groups (394 ± 25 for AD, and 403 ± 54 for healthy controls).

Table 1.

Participant demographics at baseline and year one.

| Baseline |

Year one |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | HC | AD vs. HC⁎ | AD | HC | AD vs. HC⁎ | |

| Age | 75.8 ± 7.6 | 73.0 ± 6.6 | p = 0.104 | 76.9 ± 7.7 | 74.1 ± 6.5 | p = 0.114 |

| # of males | 24 | 17 | p = 0.113 | – | – | – |

| # of females | 10 | 16 | – | – | – | |

| Education | 15.7 ± 2.9 | 16.4 ± 2.8 | p = 0.347 | – | – | – |

t-Tests used to obtain p-values.

All ADNI participants provided informed written consent approved by each sites' Institutional Review Board. Secondary data use for the current study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Victoria, in British Columbia, Canada.

2.2. Image acquisition

MRI data were downloaded from the ADNI2 database. All participants underwent whole-brain MRI scans according to the ADNI protocol. Images were acquired from 3 T MRI scanners (GE Medical Systems) from seven North American sites. Axial diffusion weighted image data were acquired with a spin echo planar imaging sequence. Scan parameters are as follows: acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, voxel size = 1.4 × 1.4 × 2.7 mm3, flip angle = 90°, number of slices = 59. There were 46 images acquired for each scan: 41 diffusion-weighted images (b = 1000 s/mm2) and 5 non-diffusion-weighted images (b = 0 s/mm2). Repetition time varied across scanning sites, but was approximately 12,500 to 13,000 ms.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Image preprocessing

All data analyses were performed in Functional MRI of the Brain Software Library (FSL) version 5.0 (Analysis Group, FMRIB, Oxford, UK, http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk; Smith et al., 2004). Diffusion weighted images were corrected for eddy current distortions and head movement using Eddy Correct and non-brain tissue was removed using Brain Extraction Tool (Smith, 2002). Brain-extracted images were then visually inspected to confirm accurate results.

2.3.2. Image analysis

FA maps were created using DTIfit and input into Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) to obtain a projection of all participants' FA data onto a mean FA skeleton (Smith et al., 2006). First, all participants' FA data were non-linearly aligned to a common space (FMRIB58_FA). Then, the mean FA image was created and thresholded (FA > 0.2) to create the mean FA skeleton. Next, each participant's FA data was projected onto the thresholded mean FA skeleton. Voxelwise statistical analysis of the white matter skeleton was performed using Randomise, FSL's nonparametric permutation inference tool. Threshold free cluster enhancement was used to correct for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05). TBSS was also performed for MD; non-linear registration estimated from the FA images was applied to MD data and each participant's MD image was projected onto the mean FA skeleton before applying voxelwise statistics.

2.3.3. Statistical comparisons

Within-group comparisons were made for individuals with AD from baseline to year one, and for healthy controls from baseline to year one. Additionally, between-group contrast comparisons were made between individuals with AD and healthy controls at both baseline and at year one. White matter regions were identified with Johns Hopkins University's white matter atlas available in FSL (Mori et al., 2008, Wakana et al., 2007).

3. Results

3.1. Within-group microstructural white matter changes in individuals with AD and healthy controls at baseline and year one

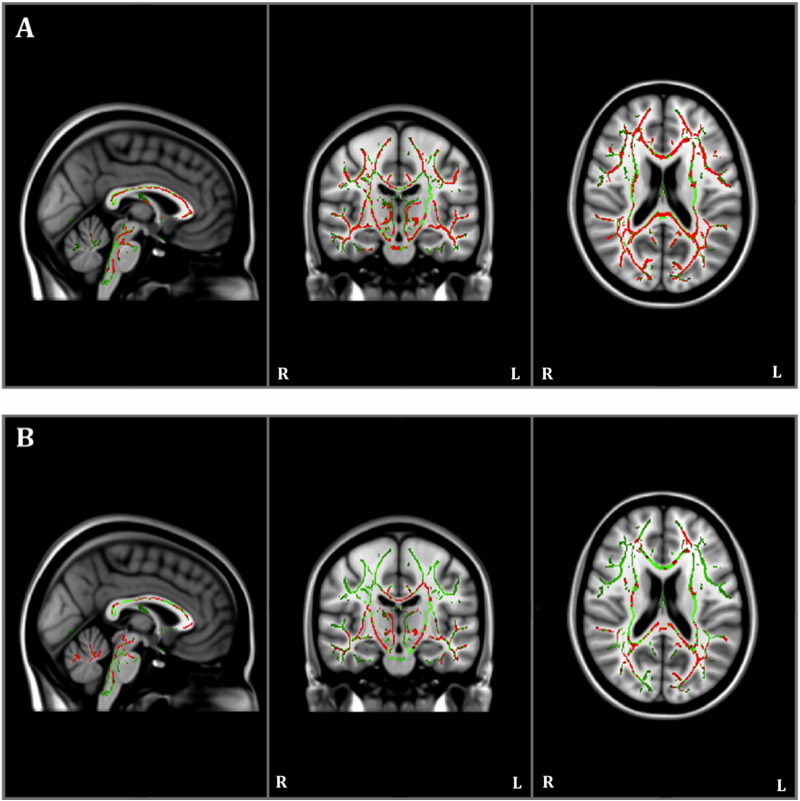

The within-group FA analysis showed that individuals with AD had reductions in FA in multiple regions, including the hippocampal cingulum, at year one compared to baseline (Table 2; Fig. 1A). Healthy controls also had reduced FA in similar regions across time, but these alterations were less extensive (as is visible in Fig. 1), and did not include the hippocampal cingulum (Fig. 1B). There were no significant increases in FA at year one compared to baseline in either group.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of total significant voxels in regions with significantly (decreased) fractional anisotropy and/or (increased) mean diffusivity at year one compared to baseline in individuals with Alzheimer's disease and in healthy controls.

| White matter regions | Alzheimer's disease |

Healthy controls |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | MD | FA | MD | |

| Corpus callosum | 5842 (77.3%) |

5087 (67.3%) |

3715 (49.2%) |

3700 (49.0%) |

| Internal capsule | 2868 (59.8%) |

2247 (46.8%) |

1769 (36.9%) |

2368 (49.4%) |

| External capsule | 2195 (70.7%) |

1537 (49.5%) |

1017 (32.8%) |

1297 (41.8%) |

| Corona radiata | 3710 (49.7%) |

4538 (60.7%) |

1794 (24.0%) |

3079 (41.2%) |

| Posterior thalamic radiations | 1809 (80.8%) |

1144 (51.1%) |

1351 (60.3%) |

996 (44.5%) |

| Longitudinal fasciculi | 1775 (56.5%) |

1453 (46.2%) |

312 (9.9%) |

953 (30.3%) |

| Fronto-occipital fasciculi | 3 (30.0%) |

3 (30.0%) |

3 (30.0%) |

5 (50.0%) |

| Cingulum (white matter of cingulate gyri) | 758 (77.4%) |

374 (38.2%) |

239 (24.4%) |

305 (31.2%) |

| Hippocampal cingulum | 272 (70.1%) |

218 (49.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Fornix | 393 (56.9%) |

243 (35.2%) |

322 (46.6%) |

333 (48.2%) |

| Corticospinal tract | 338 (54.7%) |

254 (41.1%) |

290 (46.9%) |

212 (34.3%) |

| Uncinate Fasciculus | 90 (75.0%) |

55 (45.8%) |

30 (25.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Tapetum | 38 (95.0%) |

36 (90.0%) |

14 (35.0%) |

9 (47.5%) |

| Medial lemniscus | 227 (55.4%) |

218 (53.2%) |

157 (38.3%) |

183 (44.6%) |

| Cerebellar peduncle | 2402 (65.2%) |

1837 (49.9%) |

1834 (49.8%) |

1381 (37.5%) |

| Cerebral peduncle | 873 (66.3%) |

496 (37.7%) |

756 (57.4%) |

647 (49.1%) |

Fig. 1.

Results of within-group Tract-Based Spatial Statistics white matter analysis showing pattern of reduced fractional anisotropy (red) overlaid on the white matter skeleton (green) at year one compared to baseline in individuals with Alzheimer's disease (panel A) and in healthy controls (panel B; p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

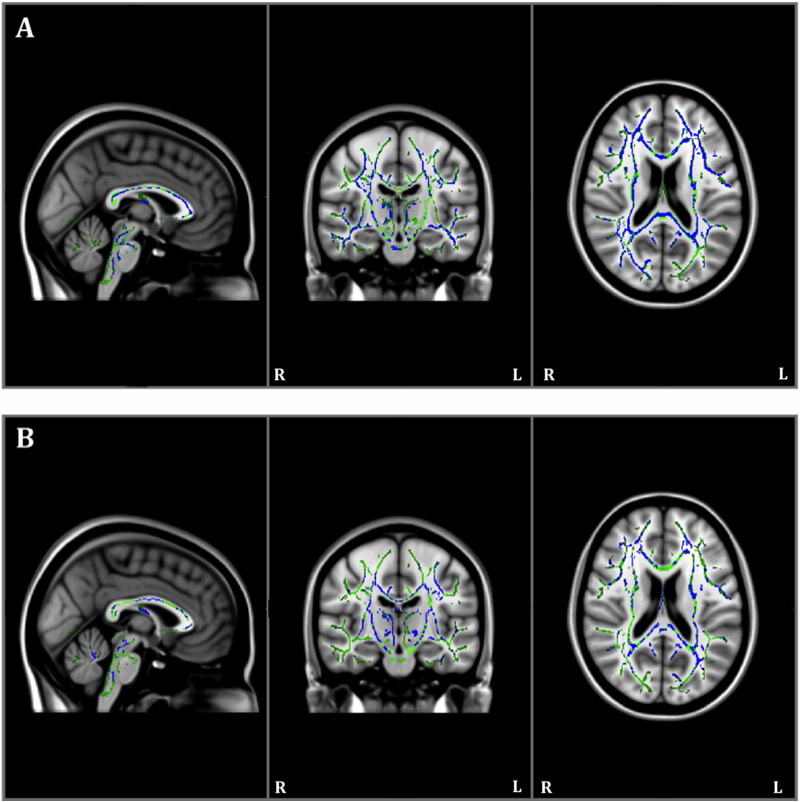

The within-group MD analysis showed that individuals with AD also had increased MD in multiple regions including the hippocampal cingulum at year one compared to baseline (Table 2; Fig. 2A). Healthy controls also had increased MD at year one compared to baseline, but once again, these alterations were less extensive than in AD, and did not include the hippocampal cingulum (Fig. 2B). There were no significant decreases in MD at year one compared to baseline in either group.

Fig. 2.

Results of within-group Tract-Based Spatial Statistics white matter analysis showing pattern of increased mean diffusivity (blue) overlaid on the white matter skeleton (green) at year one compared to baseline in individuals with Alzheimer's disease (panel A) and in healthy controls (panel B; p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

3.2. Between-group differences in individuals with AD and healthy controls at baseline and year one

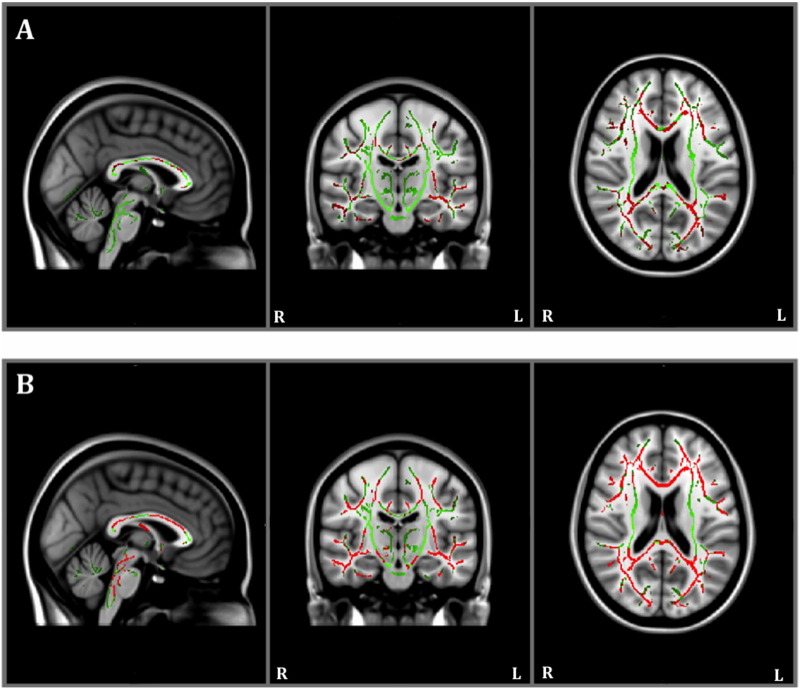

At baseline, between-group TBSS revealed that individuals with AD had lower FA relative to healthy controls (Table 3; Fig. 3A). At year one, individuals with AD also had lower FA relative to healthy controls, and these alterations appeared more widespread than at baseline (Fig. 3B).

Table 3.

Number and percentage of total significant voxels in regions with low fractional anisotropy and high mean diffusivity in individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD) compared to healthy controls (HC) at baseline and at year one.

| White matter regions | Baseline |

Year one |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD < HC FA |

AD > HC MD |

AD < HC FA |

AD > HC MD |

|

| Corpus callosum | 4378 (57.9%) |

5076 (67.2%) |

6306 (83.0%) |

6327 (83.3%) |

| Internal capsule | 555 (11.6%) |

1264 (26.3%) |

1675 (34.8%) |

1468 (30.5%) |

| External capsule | 845 (27.2%) |

927 (29.9%) |

1800 (58.1%) |

1327 (42.8%) |

| Corona radiata | 2981 (39.9%) |

5678 (76.0%) |

3566 (48.1%) |

6424 (86.6%) |

| Posterior thalamic radiation | 1233 (55.1%) |

1092 (48.8%) |

1496 (66.4%) |

1096 (48.7%) |

| Longitudinal fasciculi | 909 (28.9%) |

1826 (58.1%) |

1535 (48.7%) |

2135 (67.7%) |

| Fronto-occipital fasciculi | 0 (0.0%) |

2 (20.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (40.0%) |

| Cingulum (white matter of cingulate gyri) | 597 (61.0%) |

423 (43.2%) |

856 (90.4%) |

535 (56.5%) |

| Hippocampal cingulum | 351 (90.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

142 (35.3%) |

168 (41.8%) |

| Fornix | 339 (49.1%) |

297 (43.0%) |

581 (85.7%) |

356 (52.5%) |

| Corticospinal tract | 0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

70 (11.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Uncinate fasciculus | 70 (58.3%) |

43 (35.8%) |

94 (77.7%) |

69 (57.0%) |

| Tapetum | 38 (95.0%) |

39 (97.5%) |

36 (97.3%) |

37 (100.0%) |

| Medial lemniscus | 0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

251 (64.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Cerebellar peduncle | 0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1662 (47.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Cerebral peduncle | 0 (0.0%) |

9 (0.7%) |

751 (56.9%) |

3 (0.2%) |

Fig. 3.

Results of between-group baseline (panel A) and year one (panel B) Tract-Based Spatial Statistics white matter analysis showing pattern of lower fractional anisotropy (red) overlaid on the white matter skeleton (green) in individuals with Alzheimer's disease compared to healthy controls (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

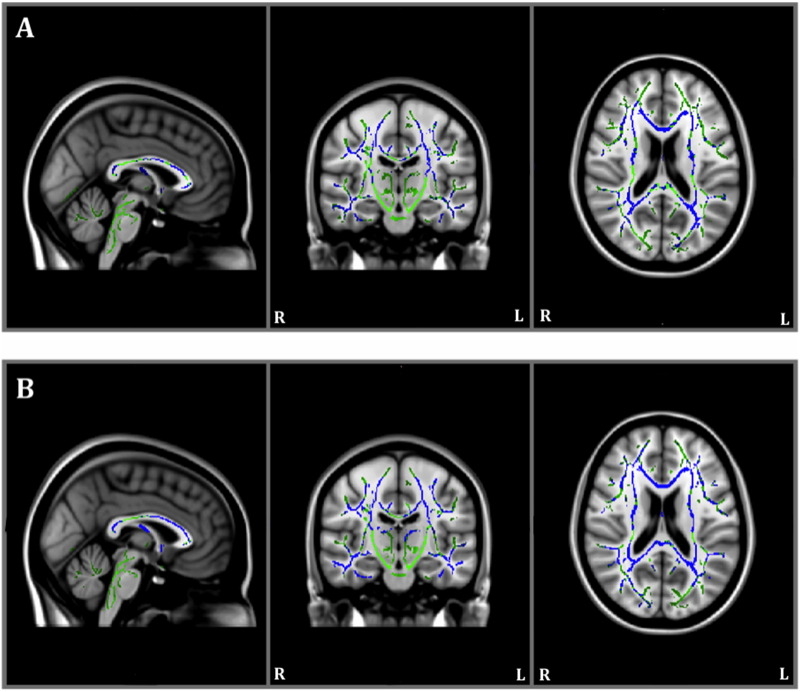

The between-group TBSS also revealed that individuals with AD had higher MD relative to healthy controls at baseline (Table 3; Fig. 4A). At year one, individuals with AD had higher MD relative to healthy controls in similar regions as baseline, but there were also patterns of higher MD in the hippocampal cingulum, not seen at baseline (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Results of between-group baseline (panel A) and year one (panel B) Tract-Based Spatial Statistics white matter analysis showing pattern of mean diffusivity (blue) overlaid on the white matter skeleton (green) in individuals with Alzheimer's disease compared to healthy controls (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

No regions demonstrated greater FA or lower MD in HC compared to AD for either time point.

4. Discussion

The current study is the first to examine longitudinal white matter changes using DTI data from the ADNI2 cohort. DTI indices of FA and MD were focused on in the current study, given that these are the most commonly reported metrics and can be interpreted in the context of recent literature (Amlien and Fjell, 2014).

The primary objective of the current study was to examine longitudinal white matter changes in individuals with AD and healthy aging. Significant changes in FA and MD were observed both in individuals with AD as well as in healthy controls at one year follow up. As expected, individuals with AD demonstrated decreased FA and increased MD in widespread white matter tracts (see Table 2 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2), including the hippocampal cingulum at year one compared to their baseline assessment. While healthy controls also exhibited decreased FA and increased MD in widespread white matter tracts (see Table 2 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2), these changes were less extensive than those observed in AD participants. Furthermore, healthy controls did not demonstrate FA or MD changes in the hippocampal cingulum as were observed in those with AD. Thus, the relatively widespread changes in larger white matter tracts seen in healthy controls may reflect age-related health factors such as vascular risk factors and the accumulation of other co-morbid health conditions (e.g., Vassilaki et al., 2016). However, changes in microstructural integrity for the hippocampal cingulum over short time intervals (i.e. one year) may more specifically reflect ongoing degenerative process due to AD.

The second objective of the current study was to investigate between-group differences in individuals with AD and healthy controls at both baseline and year one. As predicted, significant between-group differences in FA and MD were observed in multiple regions at both time points (Table 3, Fig. 3, Fig. 4), including regions of the medial temporal lobe (e.g., hippocampal cingulum). Such between-group white matter differences are in line with previous cross-sectional studies that have observed DTI alterations in the same regions (i.e. corpus callosum, superior or inferior longitudinal fasciculus; cingulate; cingulum; fornix; and uncinate fasciculus) when comparing individuals with AD to age-matched healthy controls (Agosta et al., 2011, Bosch et al., 2012, Douaud et al., 2011, Lim et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2011, Parente et al., 2008, Salat et al., 2010, Serra et al., 2010, Shu et al., 2011, Sousa Alves et al., 2012, Stricker et al., 2009). Lower FA and higher MD in AD relative to controls at each time point likely reflects the more extensive and pathological neurodegeneration observed in AD. In particular, lower FA and higher MD in the hippocampal region is consistent with the early pathological progression of AD (Braak and Braak, 1991, Hampel et al., 2014) as well as memory loss as an initial and primary concern (Alzheimer's Association, 2014).

Although there have been few longitudinal DTI studies on individuals with AD, our findings are largely consistent with those published to date (Genc et al., 2016, Kitamura et al., 2013, Norwrangi et al., 2013), demonstrating that such findings may be generalizable across AD populations — especially, given ADNI's multi-site collection. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the pathological progression observed in AD. In particular, the observed decreases in FA and increases in MD likely reflect the progressive loss of the water diffusion-restricting barriers in white matter (e.g., decreased level of myelination, loss of axons) as a consequence of neurodegeneration (Bosch et al., 2012, Kantarci, 2014, Serra et al., 2010). Currently, the mechanisms underlying white matter pathology in AD are not well understood. It is hypothesized that some damage to white matter may occur secondarily to grey matter pathology via Wallerian degeneration, but additional white matter alterations may also occur independent from grey matter pathology, as put forth by the retrogenesis hypothesis, for example (Amlien and Fjell, 2014, Bartzokis et al., 2007).

In summary, the current whole brain DTI study found evidence of a higher rate of decline in FA and increase in MD over approximately one year in individuals with AD versus matched healthy controls. These differential changes were seen in a number of white matter regions that correspond to regions know to be affected in AD. Importantly however, these DTI changes were evident in the hippocampal cingulum only in those with AD and not healthy controls, a finding that is consistent with the known pattern of progression of AD pathology in the grey matter of medial temporal regions (Braak and Braak, 1991). Volume reduction in the hippocampal grey matter is well documented in previous AD research (Hampel et al., 2014). The current findings suggest there are microstructural alterations in hippocampal white matter as well. It is currently unknown whether microstructural changes can be detected earlier than volumetric changes. Thus, future work should focus on both hippocampal grey and white matter, given that the observed hippocampal changes appear specific to AD relative to aging.

A potential limitation of the current study concerns the criteria used to diagnose AD. There are varying definitions of AD, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria may differ across studies, making cross-study comparisons and generalizations to all individuals with AD challenging. Furthermore, there is heterogeneity in the ADNI AD sample; disease stage may not be equivalent in the baseline scans and there is no pathological verification of diagnosis for all members of the AD cohort.

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) of presumed vascular origin were not accounted for in the current analysis. This represents a potential limitation as WMH are common in older adults and have been shown to be related to lower FA and higher MD relative to normal appearing white matter (e.g., Munoz Maniega et al., 2015). However, the ADNI database has previously been shown to have participants with lower levels WMH relative to other large-scale data sources (Ramirez et al., 2016). Future DTI studies in aging populations may consider including WMH to overcome this limitation.

Additionally, although the ADNI2 database includes neuroimaging data from individuals diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the current study did not examine this group, as the primary objective was to characterize white matter in AD, specifically. Approximately 10 to 15 percent of individuals with MCI progress to AD annually (Gong et al., 2013), in contrast to the 1 to 2 percent of healthy older adults who progress to AD per year (Petersen, 2004). Thus, future studies of longitudinal DTI changes in those with MCI may be helpful in determining whether the DTI changes noted in our AD sample represent sensitive and specific neuroimaging biomarkers of AD pathophysiologic processes in individuals in the prodromal stages of this disease. It is important to recognize that MCI cannot be considered synonymous with early AD (Balthazar et al., 2009). As noted by Dubois (2000), MCI applies to a heterogeneous group of aging adults with cognitive concerns, regardless of the underlying etiology or symptom progression. Future studies are likely to require relatively large and well-characterized study samples, longer follow up periods to adequately observe conversion from MCI to AD, as well as multimodal imaging protocols in order to adequately address this issue.

Data collection for ADNI2 is currently ongoing. As new data are added to the database, the current findings should provide support for additional analyses of DTI white matter changes to assist in the development of potential biomarkers of AD. Future studies that draw from the ADNI database will benefit from these multi-year longitudinal data (up to five years). Not only will the number of participants in each study group grow as additional participants are recruited, the trajectory of the disease progression can be better tracked across longer time periods as data collection with the current cohort continues.

5. Conclusion

A major focus of research on AD centres on the investigation of biomarkers. To date, most studies have focused on changes in grey matter and taken a cross sectional approach. The current study is the first to examine longitudinal white matter changes using the ADNI2 cohort. The results revealed that changes in FA and MD occurred over a one year period in both patients with AD and healthy controls, although the changes were more extensive in AD and more specific to the medial temporal lobe. DTI holds potential as an AD biomarker though multi-year tracking of brain imaging and AD clinical signs at different diagnostic stages are needed to fully evaluate its clinical utility. Ultimately, better characterization of longitudinal microstructural white matter changes may lead to pre-symptomatic detection and better outcomes for individuals with AD.

Funding

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

The current study was also supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Competition: 201310): Catalyst Grant for the Secondary Analyses of Neuroimaging Databases and the Canada Graduate Scholarships [grant number CSE 133352]; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada [grant number PDF-454132-2014] and CREATE; Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions [grant number 201300567].

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Mauricio Garcia-Barrera for the thoughtful comments during the writing of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Chantel D. Mayo, Email: cmayo@uvic.ca.

Erin L. Mazerolle, Email: emazerol@ucalgary.ca.

Lesley Ritchie, Email: lritchie3@exchange.hsc.mb.ca.

John D. Fisk, Email: John.Fisk@nshealth.ca.

Jodie R. Gawryluk, Email: gawryluk@uvic.ca.

References

- Acosta-Cabronero J., Nestor P.J. Diffusion tensor imaging in Alzheimer's disease into the limbic-diencephalic network and methodological considerations. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agosta F., Pievani M., Sala S., Geroldi C., Galluzzi S., Frisoni G., Filippi M. White matter damage in Alzheimer disease and its relationship to gray matter atrophy. Neuroradiology. 2011;258:853–863. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander A.L., Lee J.E., Lazar M., Field A.S. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;7:316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative ADNI 2 Procedures Manual. 2008. https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/adni2-procedures-manual.pdf Retrieved from.

- Alzheimer's Association 2014 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:e47–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlien I.K., Fjell A.M. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter degeneration in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroscience. 2014;276:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar M.L.F., Yasuda C.L., Pereira R.F., Pedro T., Damasceno B.P., Cendes F. Differences in grey and white matter atrophy in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009;16:468–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G., Lu P.H., Mintz J. Human brain myelination and amyloid beta deposition in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach T.G., Monsell S.E., Phillips L.E., Kukull W. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's disease centers. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012;71:266–273. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31824b211b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch B., Arenaza-Urquijo E.M., Rami L., Sala-Llonch R., Junque C., Sole-Padulles C., Pena-Gomex C., Bargall N., Molinuevo J.L., Bartres-Fax D. Multiple DTI index analysis in normal aging, amnestic MCI and AD: relationship with neuropsychological performance. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska A.Z., Preuschhof C., Backman L., Nyberg L., Li S.C., Lindenberger U., Heekeren H.R. Age-related differences in white matter microstructure: region-specific patterns of diffusivity. NeuroImage. 2010;49:2104–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash D.M., Rohrer J.D., Ryan N.S., Ourselin S., Fox N.C. Imaging endpoints for clinical trials in Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2014;6:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0087-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaud G., Jbabdi S., Behrens T.E., Menke R.A., Monsch A.U., Rao A., Whitcher B., Kindlmann G., Matthews P.M., Smith S. DTI measures in cross-fibre areas: increased diffusion anisotropy reveals early white matter alternation in MCI and mild Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2011;55:880–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B. Prodromal Alzheimer's disease: a more useful concept than mild cognitive impairment? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2000;13:367–369. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Feldman H., Jacova C., Cummings J.L., DeKosky S.T., Barberger-Gateau P., Delacourte A., Frisoni G., Fox N.C., Galasko D., Gauthier S., Hampel H., Jicha G.A., Meguro K., O'Brien J., Pasquier F., Robert P., Rossor M., Salloway S., Sarazin M., de Souza L.C., Stern Y., Visser P.J., Scheltens P. Revising the definition of Alzheimer's disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc S., Steward C.E., Malpas C.N.B., Velakoulis D., O'Brien T.J., Desmond P.M. Short-term white matter alterations in Alzheimer's disease characterized by diffusion tensor imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2016;3:627–634. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B.T. White matter integrity and vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease: preliminary findings and future directions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong N., Wong C., Chan C., Leung L., Chu Y. Correlations between microstructural alterations and severity of cognitive deficiency in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a diffusional kurtosis imaging study. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2013;31:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H., Lista S., Teipel S.J., Garaci F., Nistico R., Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Bertram L., Duyckaerts C., Bakardijan H., Drzezga A., Colliot O., Epelbaum S., Broich K., Lehericy S., Brice A., Khachaturian Z.S., Aisen P.S., Dubois P.S. Perspective on future role of biological markers in clinical therapy trials of Alzheimer's disease: a long-range point of view beyond 2020. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;88:426–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J.A., Higgins G.A. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K. Fractional anisotropy of the fornix and hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:1–4. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S., Kiuchi K., Taoka T., Hashimoto K., Ueda S., Yasuno F., Morkawa M., Kichikawa K., Kishimoto Longitudinal white matter changes in Alzheimer's disease: a tractography-based analysis study. Brain Res. 2013;1515:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.K., Kim S.J., Choi C.G., Lee J., Kim S.Y., Kim H.J., Kim N., Jahng G. Evaluation of white matter abnormality in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment using diffusion tensor imaging: a comparison of tract-based spatial statistics with voxel-based morphometry. J. Korean Soc. Magn. Resonan. Med. 2012;16:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Spulber G., Lehtimaki K.K., Kononen M., Hallikainen I., Grohn H., Kivipelto M., Hallikain M., Vanninen R., Soininen H. Diffusion tensor imaging and tract-based spatial statistics in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:1558–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart S.N., Decarli C. Structural imaging measures of brain aging. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2014;24:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9268-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz Maniega S., Valdes Hernandez M.C., Clayden J.D., Royle N.A., Murray C., Morris Z., Aribisala B.S., Gow A.J., Starr J.M., Bastin M.E., Deary I.J., Wardlaw J.M. White matter hyperintensities and normal-appearing white matter integrity in the aging brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G., Drachman D., Folster M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Service task force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S., Oishi K., Jiang H., Jiang L., Li X., Akhter K., Hua K., Faria A.V., Mahmood A., Woods R., Toga A., Puke B., Rosa Neto P., Evans A., Zhang J., Huang H., Miller M.I., van Zijl P., Mazziotta J. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. NeuroImage. 2008;40:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwrangi M.A., Lyketsos C.G., Leoutsakos J.M.S., Oishi K., Albert M., Mori S., Mielke M.M. Longitudinal, region-specific course of diffusion tensor imaging measures in mild cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.05.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente D.B., Gasparetto E.L., Celso Hygino d., Cruz L., Cortez Domingues R., Baptistta A.C., Carvalho A.C.P., Cortes Domingues R. Potential role of diffusion tensor MRI in the differential diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008;190:1369–1374. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl D.P. Neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Mt Sinai J. Med. 2010;77:32–42. doi: 10.1002/msj.20157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez J., McNeely A.A., Scott C.J.M., Masellis M., Black S.E., Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative White matter hyperintensity burden in elderly cohort studies: The Sunnybrook Dementia Study, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, and three-city study. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.06.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat D.H., Tuch D.S., van der Kouwe A.J.W., Greve D.N., Pappu V., Lee S.Y., Hevelone N.D., Zaleta A.K., Growdon J.H., Corkin S., Fischel B., Rosas H.D. White matter pathology isolates the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010;31:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra L., Cercignani M., Lenzi D., Perri R., Fadda L., Caltagirone C., Macaluso E., Bozzali M. Grey and white matter changes at different stages of Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:147–159. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton C.E., Kalu U.G., Filippini N., MacKay C.E., Ebmeier K.P. A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:2322.e5–2322.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu N., Wang Z., Qi Z., Li K., He Y. Multiple diffusion indices reveals white matter degeneration in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a tract-based spatial statistics study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:275–285. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Jenkinson M., Woolrich M.W., Beckmann C.F., Behrens T.E.J., Johansen-Berg H., Bannister P.R., De Luca M., Drobnjak I., Flitney D.E., Niazy R.K., Saunders J., Vickers J., Zhang Y., De Stefano N., Brady J.M., Matthews P.M. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Jenkinson M., Johansen-Berg H., Rueckert D., Nichols T.E., Mackay C.E., Watkins K.E., Ciccarelli O., Zaheer Cader M., Matthews P.M., Behrens T.E.J. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares J.M., Marques P., Alves V., Sousa N. A hitchhiker's guide to diffusion tensor imaging. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Alves G.S., O'Dwyer L., Jurcoane A., Oertel-Knochel V., Knochel C., Prvulovic D., Sudo F., Alves C.E., Valente L., Moreira D., Fuber F., Karakaya T., Pantel J., Engelhardt E., Laks J. Different patterns of white matter degeneration using multiple diffusion indices and volumetric data in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins G.T., Murphy C.M. Diffusion tensor imaging in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Behav. Neurol. 2009;21:39–49. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2009-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker N.H., Schweinsburg B.C., Delano-Wood L., Wierenga C.E., Bangen K.J., Haaland K.Y., Frank L.R., Salmon D.P., Bondi M.W. Decreased white matter integrity in late-myelinating fibre pathways in Alzheimer's disease supports retrogenesis. NeuroImage. 2009;45:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoub T.R., deToledo-Morrell L., Dickerson B.C. Parahippocampal white matter volume predicts Alzheimer's risk in cognitively normal old adults. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:1855–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teipel S.J., Meindl T., Wagner M., Stieltjes B., Reuter S., Hauenstein K.H., Filippi M., Ernemann U., Reiser M.F., Hampel H. Longitudinal changes in fiber tract integrity in healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment: a DTI follow-up study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:507–522. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki M., Aakre J.A., Mielke M.M., Geda Y.E., Kremers W.K., Alhurani R.E., Machulda M.M., Knopman D.S., Petersen R.C., Lowe V.J., Jack C.R., Roberts R.O., Jr. Multimorbidity and neuroimaging biomarkers among cognitively normal persons. Neurology. 2016;86:2077–2084. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakana S., Caprihan A., Panzenboeck M.N., Fallon J.H., Perry M., Gollub R.L., Hua K., Zhang J., Jiang H., Dubey P., Blitz A., van Zijl P., Mori S. Reproducibility of quantitative tractography methods applied to cerebral white matter. NeuroImage. 2007;36:630–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Benzinger T.L., Su Y., Christensen J., Friedrichsen K., Aldea P., McConathy J., Cairns N.J., Fagan A.M., Morris J.C., Ances B.M. Evaluation of tau imaging in staging Alzheimer's disease and revealing interactions between b-amyloid and taupathy. JAMA Neurol. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2078. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO Media Centre; 2016. Dementia Fact Sheet.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/ [Google Scholar]