Abstract

Introduction

The social developmental processes by which child maltreatment increases risk for marijuana use are understudied. This study examined hypothesized parent and peer pathways linking preschool abuse and sexual abuse with adolescent and adult marijuana use.

Methods

Analyses used data from the Lehigh Longitudinal Study. Measures included child abuse (physical abuse, emotional abuse, domestic violence, and neglect) in preschool, sexual abuse up to age 18, adolescent (average age = 18 years) parental attachment and peer marijuana approval/use, as well as adolescent and adult (average age = 36 years) marijuana use.

Results

Confirming elevated risk due to child maltreatment, path analysis showed that sexual abuse was positively related to adolescent marijuana use, whereas preschool abuse was positively related to adult marijuana use. In support of mediation, it was found that both forms of maltreatment were negatively related to parental attachment, which was negatively related, in turn, to having peers who use and approve of marijuana use. Peer marijuana approval/use was a strong positive predictor of adolescent marijuana use, which was a strong positive predictor, in turn, of adult marijuana use.

Conclusions

Results support social developmental theories that hypothesize a sequence of events leading from child maltreatment experiences to lower levels of parental attachment and, in turn, higher levels of involvement with pro-marijuana peers and, ultimately, to both adolescent and adult marijuana use. This sequence of events suggests developmentally-timed intervention activities designed to prevent maltreatment as well as the initiation and progression of marijuana use among vulnerable individuals.

Keywords: child abuse, parental attachment, peers, marijuana use, adolescence, adulthood

1. Introduction

Rates of marijuana use in youth are high. In the United States, 6.5% of 8th graders and 21.2% of 12th graders report marijuana use within the past week (Miech, Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015). These rates are particularly elevated among youth who have experienced child abuse or neglect (Dubowitz et al., 2016). The harmful effects of regular, heavy use of marijuana are well documented (Fergusson, Horwood, & Swain-Campbell, 2002; Hall, 2015; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014). With the possibility of even greater access to marijuana in the growing number of states where it has become legalized (Mason et al., 2016), it is important to understand processes that relate to the adoption and maintenance of marijuana use, particularly among maltreated youth. However, research has not yet revealed the social developmental mechanisms by which exposure to child maltreatment might lead to marijuana involvement in adolescence and adulthood. The current study addresses this gap by testing parent and peer pathways leading from child physical abuse and neglect as well as sexual abuse to adolescent and adult marijuana use.

Child maltreatment is associated with the use of multiple substances in adolescence (Dembo et al., 1992; Harrison, Fulkerson, & Beebe, 1997; Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004) and adulthood (Horan & Widom, 2015; Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2010; Lo & Cheng, 2007). Hovdestad, Tonmyr, Wekerle, and Thornton (2011) recommend that research in this area examine multiple types of maltreatment. Dubowitz et al. (2016) reported statistically significant bivariate predictive associations of child physical and sexual abuse with marijuana use in a prospective study of adolescents. Only sexual abuse retained a statistically significant association with marijuana use in analyses that adjusted for study site, participant sex, and race/ethnicity. Dubowitz et al. (2016) concluded that “Future research should focus on better understanding the mechanisms by which physical and sexual abuse influence youth adolescent risk taking behaviors in general and marijuana use in particular” (p. 7). Few such mediation tests have been conducted.

Oshri, Rogosch, Burnette, and Cicchetti (2011) examined personality functioning (ego undercontrol and ego resiliency) as well as psychopathology (externalizing and internalizing problems) as mediators of the link between child maltreatment and cannabis use disorder symptoms in adolescence. Results provided support for a personality functioning – externalizing pathway, but not for a personality functioning – internalizing pathway. Additional studies have similarly examined individual characteristics (e.g., depression) as mediating mechanisms in the association of child maltreatment with marijuana and other substance use (Horan & Widom, 2015; Lansford et al., 2010; Lo & Cheng, 2007).

Informative as these studies have been, their focus on individual characteristics leaves the potential parenting and peer socialization processes linking child maltreatment with marijuana use largely unexamined. However, social developmental theories suggest that such processes are important considerations. These types of theories were classified by Petraitis, Flay, and Miller (1995) as falling within the social/interpersonal sphere, and commonly draw from social control and social learning principles. Social control theory focuses on the socializing influence of the family in childhood and adolescence, particularly the protective effect of parental involvement and attachment on deviant behaviors (Hirschi, 1969). Chen, Storr, and Anthony (2005) found that parental involvement in the elementary and middle school years shields youth from experimenting with marijuana. Conversely, Kandel and colleagues (Kandel, Kessler, & Margulies, 1978; Kandel, 1980) found that poor parent-child interactions lead to increased marijuana use, possibly by promoting association with deviants peers (Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012).

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) emphasizes deviant peers who may influence an adolescent's own deviant behavior (Dorius, Bahr, Hoffmann, & Harmon, 2004). According to Burgess and Akers (1966), individuals learn deviant behavior by observing and modeling their social contacts. Adolescents become increasingly influenced by their peers, and youth who have peers that use marijuana are more likely to use it themselves (D'Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Johnson & Marcos, 1987; Marcos, Bahr, & Johnson, 1986; Poulin, Kiesner, Pedersen, & Dishion, 2011). When adolescents feel that their friends approve of drugs, they are exposed to both psychological encouragement and observable behavior to model (Dorius et al., 2004). Accordingly, research shows that peers' favorable attitudes toward substance use and their own substance involvement are robust, proximal predictors of adolescent substance use (Kandel et al., 1978; Mason & Windle, 2001; Oetting & Beauvais, 1987; Van Ryzin et al., 2012), including marijuana initiation (Kosterman, Hawkins, Guo, Catalano, & Abbott, 2000).

Prior studies have examined the simultaneous parent and peer influences on adolescent substance use (e.g., Aseltine, 1995). Several such studies found that when peer influences were added to a model that included family variables, the family influences were reduced (Bahr & Hoffmann, 2005; Bares, Delva, Grogan-Kaylor, & Andrade, 2011). However, there is also evidence that parents exert an influence on their adolescent children through peer interactions as a mediating process; for example, van Ryzin et al. (2012) found that family factors, such as relationship quality, indirectly predicted adolescent substance use through reduced deviant peer associations.

Parent and peer predictors of adolescent problem behavior outcomes, including substance use, are influenced by earlier child maltreatment. Sousa et al. (2011) found that children exposed to abusive parenting and domestic abuse had lower levels of attachment to their parents. Lower attachment, in turn, led to a greater number of antisocial behaviors among adolescents. By contrast, Allen, Chango, Szwedo, Schad, and Marston (2012) found that teens who received a high level of support from their mothers were less likely to be swayed by their friends' level of substance use.

Although it is plausible that parent and peer socialization processes may operate as mediators linking child maltreatment with subsequent marijuana use, this remains to be tested. Dubowitz et al. (2016) reported that positive associations between child maltreatment indicators and marijuana use behaviors generally became statistically non-significant after adding peer marijuana use to the analyses. This finding is consistent with the possibility of peer mediation, but a more direct test of the longitudinal links between child maltreatment and marijuana use through peer as well as parent factors is needed.

Relatively few studies have examined the progression of marijuana or other substance use from adolescence into adulthood (e.g., Lansford et al., 2010; Mason & Spoth, 2012). Yet, the factors affecting continued marijuana use may be different from those that affect the initiation of use (Kandel, 1980). Studying alcohol progression, Mason and Spoth (2012) found that early adolescent peer deviance predicted alcohol use in middle adolescence, but not alcohol abuse in early adulthood. Findings from studies such as this suggest the need for long-term longitudinal investigations of marijuana use outcomes (e.g., initial use, maintenance) over adolescence and into the adult years.

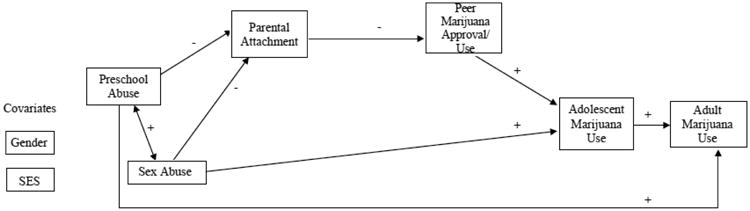

Of course, child maltreatment often occurs within a broader context characterized by additional family stressors that can influence parent and peer pathways leading toward problem outcomes. According to family process models (e.g., Conger et al., 1992), socioeconomic disadvantage has an indirect effect on a child's adjustment through parenting difficulties, since parents who are faced with economic problems are likely to experience disrupted family management and diminished marital as well as parent-child relationship quality. This highlights the need for studies of the consequences of child maltreatment for marijuana use that address socioeconomic disadvantage in the family of origin as an important background predictor. Guided by social developmental theories, this study uses longitudinal data to test the proposed model in Figure 1. It is hypothesized that child abuse and sexual abuse will be associated with lower parental attachment, which will predict, in turn, higher levels of peer as well as adolescent and adult marijuana use, controlling for socioeconomic status as well as gender.

Figure 1. Proposed Path Analysis Model for Adolescent and Adult Marijuana Use.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Data are from the Lehigh Longitudinal Study, a prospective study of the causes and consequences of child maltreatment, which began in the 1970s with a sample of 457 children in 297 families (Herrenkohl, Herrenkohl, Egolf, & Wu, 1991). Some of the families were recruited from child welfare agency abuse and neglect caseloads. Others were recruited from several group settings (i.e., Head Start, day care, and nursery programs) in the same two-county area to serve as the comparison sample. This dataset spans a 30-year period, covering four developmental periods: early- and middle-childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The first, “preschool” wave occurred in 1976 to 1977 when children were 18 months to 6 years old. A second “school-age” wave occurred in 1980 to 1982. Ten years later, in 1990 to 1992, was the “adolescence” wave, when children were on average 18 years old. Most recently, data were collected in 2008 to 2010 for an “adulthood” wave, with 357 of the original child participants (80% of those living), when they were in their mid-30s. The original child sample was roughly gender balanced (54% male). The racial and ethnic composition was relatively homogeneous (e.g., 80.7% White), but reflected the two-county area from which participants were selected. At the preschool wave, 86% of children were from a two-parent household; 63% of families reported an income level below $700 per month.

2.2 Measures

Preschool Child Abuse

Four types of abuse were measured at preschool: physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and domestic violence. A brief description of each measure is provided below (see also Herrenkohl et al., in press). The four measures were standardized and summed to produce a measure of preschool child abuse (α = .60).

Physical abuse was measured during a structured interview with parents, typically the mother, regarding the use of various discipline practices, some of which qualify as abusive (e.g., hit/paddle to bruise, shake). The severity of each abusive practice was scored on a scale from 1 (lowest severity) to 5 (highest severity) by a group of trained and experienced child welfare workers. Questions regarding abusive disciplining practices referenced practices “during the last three months” and “prior to the last three months.” The parent interviewed was also asked about the discipline practices of other caretakers (relative or nonrelatives). Practices used in the current analysis were all rated in the 4.0 to 5.0 (severely punishing to abusive) severity range. Severity weights of abusive practices used by each caretaker were summed and combined to form a composite measure of physical abuse.

Emotional abuse was assessed, scored, and scaled in the same way as physical abuse, with structured interview questions regarding seven emotionally abusive practices (e.g., locking a child out of the house, taking meals away as punishment) over the past three months across all caretakers. An emotional abuse measure was computed by summing the severity level of these seven practices, according to ratings provided by the same group of trained child welfare workers as noted above.

Neglect was a variable indexing evidence of a lack of appropriate child supervision, parents' lack of awareness of medical and dental needs, and parental emotional unavailability, as recorded in observations of parent-child interactions. Information on neglect was also compiled from child welfare records, hospital records, and preschool interviewer observations on (1) child's physical appearance (including dental care), and (2) ratings indicating the presence of any of these four conditions in the home: dirty dishes, food scraps on floor, smell of urine, or broken glass and garbage.

Domestic violence was measured at preschool by the frequency with which mother used physical acts (e.g., hit/push//kick) as a reaction to differences with her partner. A second parallel measure sums the frequencies with which the partner used physical methods in response to a disagreement.

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse data were collected during adolescence. The primary source was youth self-report, wherein youth were asked whether they had ever been sexually abused. Two additional questions focused on sexual assault and rape. Additional data sources were interviewer notes containing reports of sexual abuse, as well as child welfare case records indicating sexual abuse events in the child's lifetime. Sexual abuse is coded 1 if any sexual abuse was reported as having occurred from preschool through adolescence.

Parental Attachment

The adolescent interview included the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), yielding indices of parental communication, trust, and alienation. After reverse-coding alienation, the three indices were summed to form a measure of parental attachment (α = .88).

Peer Marijuana Approval/Use

During adolescence, perception of peer marijuana use was collected by asking, “During the last year, how many of your friends used marijuana or hashish?” Response options were: “none” (1), “very few” (2), “some” (3), “most” (4), or “all” (5). Adolescents were also asked about perceived peer approval of marijuana use on a five-point scale from “disapprove strongly” (1) to “approve strongly” (5). These two variables were summed into a measure of peer approval of/use of marijuana (α = .89).

Adolescent Marijuana Use

Self-reported marijuana use was collected by asking adolescents if they had ever used marijuana or hashish, and the frequency of such use using a 9-point scale: “never used it” (1), “did not use it in last year” (2), “less than once a month” (3), “once a month” (4), “every 2 - 3 weeks” (5), “once a week” (6), “2 - 3 times a week” (7), “once a day” (8), or “2 - 3 times a day” (9). Adolescents were also asked to estimate the amount used in the past year. These three variables were standardized and summed into a measure of adolescent marijuana use (α = .79). Descriptive analyses showed that 53% of participants in adolescence reported ever having used marijuana, with 36% reporting past year use. Those who indicated past year use reported smoking marijuana an average of 140 times (sd = 284) in the past year. Seventeen percent of adolescents who used in the past year reported using on a daily basis.

Adult Marijuana Use

Adult participants were asked if they had used marijuana or hashish in the past year. If use was reported for the past year, they were asked to estimate the number of times in the past year. The amount they used per occasion was also collected by asking “On those days when you smoked marijuana, how much did you typically smoke?”, with response options of: “a few hits on a joint” (1), “about 1 joint” (2), or “more than 1 joint” (3). These three variables were standardized and summed into a measure of adult marijuana use (α = .88). Descriptive analyses showed that 16% of participants in adulthood reported using marijuana in the past year. Those who indicated past year use reported smoking marijuana an average of 126 times (sd = 186) in the past year; 47% reported a few hits on a joint, 21% reported smoking about 1 joint, and 33% reported smoking more than 1 joint.

Covariates

The socioeconomic status of the family was based on three parent-report items from the preschool interview: mother's educational level, family after-tax income, and mother's occupational level as measured by Occupation by Prestige (National Opinion Research Center; www.norc.org) scores. Items were standardized and summed to form a socioeconomic status measure (α = .82). Gender of the child participant was also collected (1 = male, 2 = female).

2.3 Analyses

Path analysis was conducted in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) to test the hypothesized model in Figure 1 using maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation, which provides an adjustment to the standard errors under conditions in which the data are not normally distributed and also implements full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to handle missing data. Family was specified as a clustering variable to account for the fact that certain families had multiple child participants. Note that, similar to a regression analysis, the path model is just-identified; there are no over-identifying restrictions, therefore there are no degrees of freedom and the chi-square test statistic equals zero. Interest in these circumstances is in the pattern of statistically significant and non-significant path coefficients, rather than global model fit. Evidence for mediation was garnered to the extent that each path in a hypothesized mediational chain was statistically significant; this joint statistical significance approach has been shown to provide an optimal balance of enhanced statistical power and reduced bias compared to other approaches for testing mediation (Leth-Steensen & Gallitto, 2016).

3. Results

Correlations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the statistically significant paths from the analysis of the model in Figure 1. Table 2 reports unstandardized estimates, standard errors, and standardized estimates. Preschool abuse was not directly related to adolescent marijuana use. It was, however, positively related to adult marijuana use (β = .15, p < .05). Both preschool abuse (β = -.17, p < .05) and sexual abuse (β = -.23, p < .001) were negatively related to parental attachment, which was negatively related, in turn, to peer marijuana approval/use (β = -.12, p < .05). Peer marijuana approval/use had a strong positive relationship with adolescent (β = .58, p < .001) but not adult marijuana use. Sexual abuse was directly related to adolescent marijuana use (β =. 13, p < .05), over and above its pathway through peer marijuana approval/use. The strongest predictor of adult use was earlier use of marijuana during adolescence (β = 35, p < .001).

Table 1. Correlations among variables related to marijuana use.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2. Socioeconomic status | -0.039 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3. Preschool abuse | -0.106 * | -0.439 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| 4. Sexual abuse | 0.204 ** | -0.151 ** | 0.127 * | 1.000 | ||||

| 5. Parental attachment | 0.070 | 0.182 ** | -0.241 ** | -0.239 ** | 1.000 | |||

| 6. Peer marijuana approval/use | -0.097 | -0.155 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.144 ** | -0.192 ** | 1.000 | ||

| 7. Adolescent marijuana use | -0.103 * | -0.181 ** | 0.106 | 0.203 ** | -0.188 ** | 0.624 ** | 1.000 | |

| 8. Adult marijuana use | -0.083 | -0.048 | 0.148 * | 0.048 | -0.115 * | 0.179 ** | 0.326 ** | 1.000 |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | 1.46 | .00 | .02 | .26 | 31.34 | 4.64 | .00 | -.01 |

| Standard Deviation | .50 | 2.58 | 2.71 | .44 | 21.87 | 2.38 | 2.52 | 2.69 |

| N | 457 | 457 | 384 | 411 | 412 | 365 | 413 | 355 |

p < .05;

p < .01.

Figure 2. Significant Paths in Model for Adolescent and Adult Marijuana Use.

Table 2. Path Coefficients.

| Path description: Predictor/Outcome | Unstandardized Coefficient | Standard Error | Standardized Coefficient | |

| Preschool abuse | Parental attachment | -1.337* | 0.618 | -0.17 |

| Sex abuse | Parental attachment | -11.493** | 2.773 | -0.23 |

| Socioeconomic status | Parental attachment | 0.665 | 0.474 | 0.08 |

| Gender | Parental attachment | 4.311* | 2.170 | 0.10 |

| Preschool abuse | Peer marijuana approval/use | 0.053 | 0.070 | 0.06 |

| Sex abuse | Peer marijuana approval/use | 0.530 | 0.321 | 0.10 |

| Parental attachment | Peer marijuana approval/use | -0.013* | 0.006 | -0.12 |

| Socioeconomic status | Peer marijuana approval/use | -0.066 | 0.054 | -0.07 |

| Gender | Peer marijuana approval/use | -0.518* | 0.242 | -0.11 |

| Preschool abuse | Adolescent marijuana use | -0.056 | 0.055 | -0.06 |

| Sex abuse | Adolescent marijuana use | 0.730* | 0.291 | 0.13 |

| Parental attachment | Adolescent marijuana use | -0.005 | 0.005 | -0.04 |

| Peer marijuana approval/use | Adolescent marijuana use | 0.616** | 0.052 | 0.58 |

| Socioeconomic status | Adolescent marijuana use | -0.103* | 0.042 | -0.11 |

| Gender | Adolescent marijuana use | -0.349 | 0.211 | -0.07 |

| Preschool abuse | Adult marijuana use | 0.153* | 0.072 | 0.15 |

| Sex abuse | Adult marijuana use | -0.072 | 0.302 | -0.01 |

| Parental attachment | Adult marijuana use | -0.005 | 0.006 | -0.04 |

| Peer marijuana approval/use | Adult marijuana use | -0.063 | 0.072 | -0.06 |

| Adolescent marijuana use | Adult marijuana use | 0.374** | 0.085 | 0.35 |

| Socioeconomic status | Adult marijuana use | 0.096 | 0.055 | 0.09 |

| Gender | Adult marijuana use | -0.257 | 0.276 | -0.05 |

p < .05;

p < .001.

Gender (coded 1 for males and 2 for females) had a positive relationship with parental attachment (β = .10, p < .05) and a negative relationship with peer marijuana approval/use (β = - .11, p < .05). Socioeconomic status had a negative relationship with adolescent marijuana use (β = -.11, p < .05). Taken together, variables in the model explained an estimated 41% of the variance in adolescent marijuana use and 13% of the variance in adult marijuana use.

4. Discussion

Although it is known that children who experience maltreatment are at increased risk for later marijuana involvement (e.g., Dembo et al., 1992; Dubowitz et al., 2016), the parent and peer social developmental processes by which maltreatment lead to marijuana use are understudied. The current study addressed this gap by testing parental attachment and peer marijuana approval/use pathways in the associations of both child abuse and sexual abuse with adolescent and adult marijuana use, controlling for socioeconomic status and gender. Confirming elevated risk due to child maltreatment, path analyses showed that sexual abuse but not abusive parenting, in and of itself, was a direct predictor of adolescent marijuana use. Preschool child abuse, however, did have a modest direct association with marijuana use in adulthood.

As expected (e.g., Sousa et al., 2011), parental attachment was negatively predicted by both preschool abuse and sexual abuse, indicating that these maltreatment experiences disrupt parent-child relationships. Research suggests that strong parental attachment may discourage adolescents from experimenting with marijuana (Kandel et al., 1978; Kandel, 1980). This was partially supported by the current data in that parental attachment had a direct negative relationship with peer marijuana approval/use but not adolescent marijuana use. However, parents may influence their adolescent children indirectly through their influence on peer involvements and interactions (Van Ryzin et al., 2012). Indeed, results showed that parental attachment was negatively related to peer marijuana approval/use, which was positively related, in turn, to adolescent marijuana use. In fact, having friends who approve of and use marijuana was the strongest predictor of whether an adolescent became marijuana involved (e.g., D'Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Poulin et al., 2011). Thus, parents may continue to have an important, albeit potentially less direct, influence on their children's lives into the adolescent years.

A limitation of this study is that sexual abuse was measured primarily via self-report when the subjects were adolescents, as were peer marijuana-related attitudes and behaviors; such reports can be biased. Although the preschool abuse variable captured a range of maltreatment experiences, reliability of the scale was somewhat low. Where feasible, future studies should test hypothesized relationships among constructs represented as latent variables. Finally, this study examined a limited number of possible factors that could be related to marijuana use; however, guided by social developmental theory and the research question under consideration, emphasis was placed on two prominent social developmental processes that need further investigation. Future research should expand the model tested here to include other relevant factors, such as conduct problems (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2007).

5. Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the theory-guided approach, longitudinal design, and well-established path modeling procedures of this study increase confidence in the conclusions drawn. Results supported a hypothesized sequence of events leading from child maltreatment experiences to lower levels of parental attachment and, in turn, higher levels of involvement with pro-marijuana peers and, ultimately, to adolescent and adult marijuana use. This sequence suggests developmentally-timed intervention activities. Preventing early maltreatment in vulnerable families is a first step to preventing substance use as well as other adverse outcomes that often persist into adulthood. Delaying marijuana initiation may help reduce the adverse consequences associated with marijuana involvement. With the legalization of marijuana now approved or under consideration in several states across the nation, findings of the current investigation are all the more important and relevant to policy debates about how to keep young people safe from substances.

Highlights.

The mechanisms linking child maltreatment with later marijuana use are uncertain

This longitudinal study tested parent and peer social developmental mechanisms

Preschool abuse and sexual abuse were negatively related to parent attachment

Parental attachment was negatively related, in turn, to peer marijuana use

Peer marijuana use predicted adolescent and, in turn, adult marijuana use

Findings supported the hypothesized social developmental pathways to marijuana use

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tanya Williams for her valuable contributions to preparation of the manuscript.

Author Disclosures: Role of Funding Source and Author Disclosure: This work was supported by grant # R01DA032950 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant # R01HD049767 from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

With support from the grants, all authors provided substantive knowledge and expertise to the study reported herein.

Footnotes

Contributors: W. Alex Mason, M. Jean Russo, and Todd I. Herrenkohl contributed to formulation of the research questions, the primary data analyses, and the writing. Mary B. Chmelka contributed to the data analyses and the writing. Roy C. Herrenkohl contributed to the study design and data collection.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen JP, Chango J, Szwedo D, Schad M, Marston E. Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH. A reconsideration of parental and peer influences on adolescent deviance. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:103–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:529–551. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bares CB, Delva J, Grogan-Kaylor A, Andrade F. Family and parenting characteristics associated with marijuana use by Chilean adolescents. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2011;2:1–11. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S16432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R, Akers RA. Differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Social Problems. 1966;14:128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Influences of parenting practicies on the risk of having a chance to try cannabis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1631–1639. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents' substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, Schmeidler J, Berry E, Wothke W, Getreu A, et al. A structural model examining the relationship between physical child abuse, sexual victimization, and marijuana/hashish use in delinquent youth: A longitudinal study. Violence and Victims. 1992;7:41–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Thompson R, Arria AM, English D, Metzger R, Kotch JB. Characteristics of child maltreatment and adolescent marijuana use: A prospective study. Child Maltreatment. 2016;21:16–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559515620853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction. 2015;110:19–35. doi: 10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ. Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victimes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl RC, Herrenkohl EC, Egolf BP, Wu P. The developmental consequences of child abuse: The Lehigh Longitudinal Study. In: Starr RHJ, Wolfe DA, editors. The effects of child abuse and neglect: Issues and research. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Jung H, Klika JB, Mason WA, Brown EC, Leeb RT, Herrenkohl RC. Adverse effects of child maltreatment and the mitigating role of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships in the prediction of adult physical health and mental health outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkely, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Horan JM, Widom CS. Does age of onset of risk behaviors mediate the relationship between child abuse and neglect and outcomes in middle adulthood? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44:670–682. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovdestad W, Tonmyr L, Wekerle C, Thornton T. Why is childhood maltreatment associated with adolescent substance abuse? A critical review of explanatory models. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2011;9:525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Marcos AC. The role of peers in the complex etiology of adolescent drug use. Criminology. 1987;25:323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Drugs and drinking behavior among youth. Annual Review of Sociology. 1980;6:235–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kessler RC, Margulies RZ. Antecedents of adolescent initiation into stages of drug use: A developmental analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1978;7:13–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01538684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:190–194. doi: 10.1177/1077559509352359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leth-Steensen C, Gallitto E. Testing mediation in structural equation modeling: The effectiveness of the test of joint significance. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2016;76:339–351. doi: 10.1177/0013164415593777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CC, Cheng TC. The impact of childhood maltreatment on young adults' substance abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:139–146. doi: 10.1080/00952990601091119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos AC, Bahr SJ, Johnson RE. Test of a bonding/association theory of adolescent drug use. Social Forces. 1986;65:135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Fleming CB, Ringle JL, Hanson K, Gross TJ, Haggerty KP. Prevalence of marijuana and other substance use before and after Washington State's change from legal medical marijuana to legal medical and non-medical marijuana: Cohort comparisons in a sample of adolescents. Substance Abuse. 2016;37:330–335. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1071723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Spoth RL. Sequence of alcohol involvement from early onset to young adult alcohol abuse: Differential prediction and moderation by family-focused preventive intervention. Addiction. 2012;107:2137–2148. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Windle M. Family, religious, school, and peer influences on adolescent alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:44–53. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2014: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: Institute of Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide: Seventh edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Peer cluster theory, socialization characteristics, and adolescent drug use: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Rogosch FA, Burnette ML, Cicchetti D. Developmental pathways to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: child maltreatment, emerging personality, and internalizing versus externalizing psychopathology. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:634–644. doi: 10.1037/a0023151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Kiesner J, Pedersen S, Dishion TJ. A short-term longitudinal analysis of friendship selection on early adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa C, Herrenkohl TI, Moylan CA, Tajima EA, Klika JB, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ. Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:111–136. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, Dishion TJ. Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1314–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]