Abstract

Background:

In this study, the nature of food commercials in children's television (TV) was monitored and analyzed; simultaneously, the relationship between recalling TV food commercials and children's interest in them and in the consumption of the same food products was evaluated.

Methods:

A total of 108 h children's programs broadcast on two channels (Two and Amouzesh) of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) media organization were monitored (May 6–12, 2015). Simultaneously, a cross-sectional study using 403 primary schoolchildren (201 boys) in four schools of Shirvan, Northeast of Iran, was executed. The children were prompted to recall all TV commercials broadcast on IRIB. Meanwhile, they were directed to define in the list of recalled TV food commercials those were interested in and the commercials (food products) they actually were willing to consume.

Results:

Regarding the frequency and duration of broadcasting, food commercials ranked fifth and sixth, respectively. Fruit leather and plum paste were the most frequently broadcast food commercials. “High quality” (19%), “good taste” (15%), “novelty”, and “message on nutritional composition” (13%) were the most frequent messages used in promoting the sale of food products, respectively. In addition, focus on “high quality/precision in the preparation of the food products” was the most frequently used appeals in TV commercials. There was a significant relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the interest in five out of eight of the commercials (62.5%) (P < 0.05). The relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the interest in the consumption of the same food product (“Tomato paste B”) was statistically significant for 12.5% of the commercials (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

TV food commercials do not encourage healthy eating. The current study provides convincing evidence for policy-makers and researchers to pay more attention to this area.

Keywords: Children, commercial, food, television

INTRODUCTION

Despite the increase in the spread of social networks, television (TV) and its commercials are considered a significant determinant of the food choice and lifestyle of people, especially children.[1] TV commercials influence the food choices of children in different ways. Using their highfalutin and vivid messages, they encourage people to buy the advertised products.[2]

TV commercials implicitly increase the tendency of people to purchase these food products. Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable since they do not understand the profit maximization purpose of the commercials. This deficiency in understanding makes them to buy food products that are often high in fat, sugar, and salt and are nutritionally of low value.[3] In a recent study, it was revealed that the entertaining and captivating dimension of the commercials influenced the extent of unhealthy food selection by the children.[4]

Many studies have demonstrated that the majority of TV-advertised food products directed at children are high in calories and low in nutrients and against the current regulations on food commercials.[5,6,7,8,9] Therefore, it is not surprising that the high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity around the world has been attributed to watching TV.[10] In addition, by changing the children's attitude toward unhealthy food and food preferences, TV commercials can influence and shift the food choices of the family toward these types of foods.[11]

According to the available nationwide data,[12] the average amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors, including TV viewing, is two times more than recommended.[13] The high exposure of Iranian children to TV messages including food commercials may increase the chances of selection and consumption of unhealthy foods, thereby making them more prone to chronic diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have analyzed the content of food commercials on Iran TV so far.[1,14,15,16] The mentioned studies are very valuable in their own scope of study; however, they have not fulfilled some fundamental aspects of the study. First, they have not targeted the same destination; second, they have scarcely dealt with the impressibility of the audience (especially children), and third, the studies with rather similar goals are not up-to-date. Hence, the need for a recent study that overcomes the mentioned shortcomings is apt. In the present study, we explored the content of TV commercials in a period of 1 week. Thereafter, in a cross-sectional study on primary schoolchildren, the relationship between recalling TV food commercials and their interest in them and in the consumption of the same food products was evaluated.

METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Students’ Research Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code: 5587) which is in accordance with the ethical standards of Declaration of Helsinki. This study was conducted in two separate parallel parts.

Part A

All TV food commercials aired on TV 20 min before, during, and 20 min after children's and adolescents’ programs from channels “Two” and “Amouzesh” were recorded for 1 week (May 6-12, 2015) using a time recorder method. In this recording method, TV programs were automatically recorded at the stipulated time set on the device memory. During the period, there were no national, political, or religious occasions, and the week was considered normal. Children received the selected TV channels all over the country. Moreover, within a few random days of monitoring, TV commercials were more frequently broadcast on the mentioned channels compared with other channels. After recording, all commercials were repeatedly viewed, and their information was extracted and reported based on a predetermined set of instructions.

Part B

This part was a cross-sectional study conducted in May 2015 in four primary schools (two schools for each gender) in Shirvan, Northeast of Iran. Sampling was conducted using convenience sampling. Based on the formula for calculating the sample size in cross-sectional studies and taking into account an attrition of 5%, 404 primary schoolchildren (201 males and 202 females) were chosen for this study.

p: 50%, z: 1.96, attrition: 5%, and d: 0.05.

In this part of the study, the relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the primary schoolchildren's interest in them and in consumption of the same food products was examined. After obtaining the necessary approvals, four schools agreed to participate in the study. Finally, 403 children (50% boys) who had an informed consent signed by their guardians/parents were recruited.

The questionnaire was self-administered and self-reported. The questions included the date of birth, height, weight, time spent on watching TV per day, and recalled TV commercials. Thereafter, the students were directed to define in the list of recalled TV food commercials those commercials (food products) they were interested in and the commercials (food products) they actually were willing to consume.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, namely, frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were reported. The Chi-square test was performed for categorical data, and SPSS software version 22.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

To evaluate the reliability between the coders, another person coded the message. The agreement coefficient was calculated according to the formula below.[17]

The internal reliability of appeals was 87.5%, and the reliability between the coders was 82%.

Appeals are underlying content of the advertisement which are used to attract the attention of consumers and influence people's feelings toward the product or service.[18]

RESULTS

Content analysis study

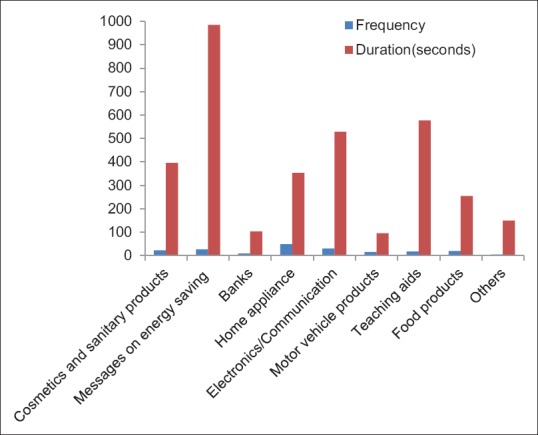

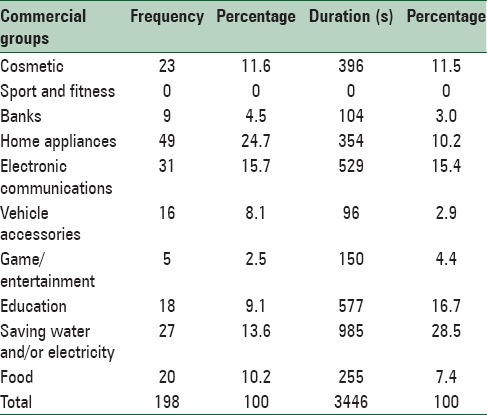

In the study period, 198 commercials were recorded in 3446 s. Food commercials comprised 10.2% of the number and 7.4% of the broadcasting duration in the studied period. In other words, regarding the frequency and duration of broadcasting, food commercials ranked fifth and sixth, respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Frequency and duration of commercials broadcasting at the time of children's programs from Channel 2 and Amouzesh, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, May 6–12, 2015

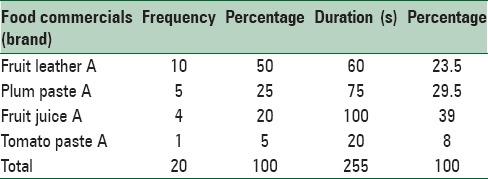

Table 1 shows the frequency and duration of TV food commercials. As seen, 75% of the food commercials were related to “fruit leather and plum paste.”

Table 1.

Frequency and duration of TV food commercials broadcasting at the time of children's programs from Channel 2 and Amouzesh, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, May 6-12, 2015

Regarding the type and frequency of the messages used to promote the sale of a product, taking into consideration the repeated commercials, “high quality” (19%), “good taste” (15%), “novelty,” and “nutritional composition” (13%) had the highest frequency in order.

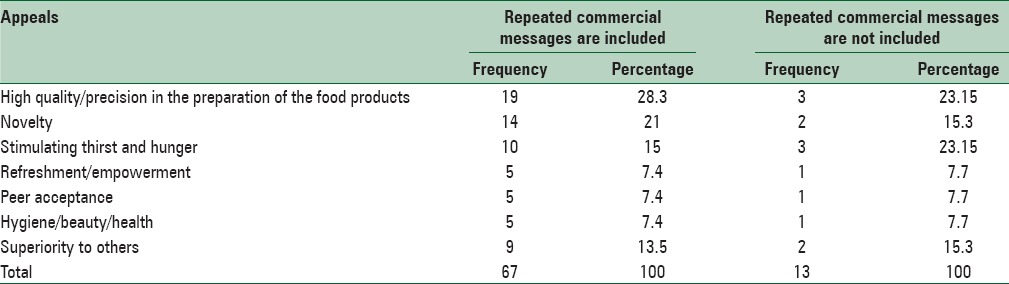

Based on Table 2, the most frequent appeals of food commercials, taking into consideration the repeated commercials, were “high quality/precision in the preparation” (28.3%), “novelty” (21%), and “stimulation of thirst and hunger” (15%) in order (repeated commercials were considered).

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage of appeals associated with food products advertised on Channel 2 and Amouzesh of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, May 6-12, 2015

The results showed that half of the food commercial messages (50%) were silent and pictorial. Thirty percent of the food commercials were presented by humans who pretended to be eating the products.

The experimental study

A total of 403 children (201 boys, 202 girls) took part in the study. The mean age of the boys and girls was 11 ± 6.8 and 10.45 ± 0.7, respectively.

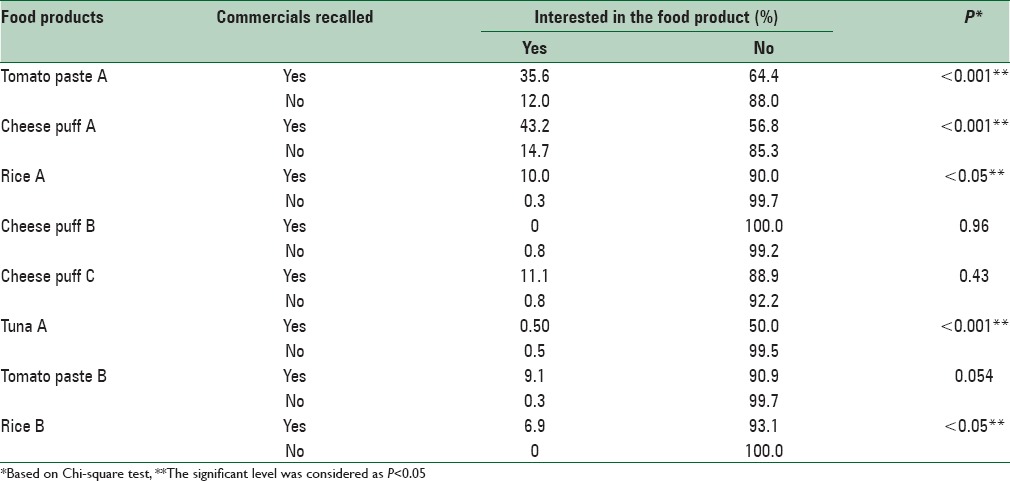

According to Table 3, the relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the interest in five out of eight of the commercials (62.5%) was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

The relationship between recalling TV food commercial and being interested in them among primary schoolchildren of Shirvan, May 10-11, 2015

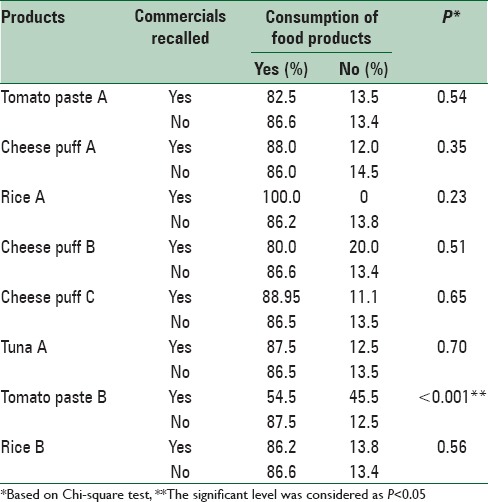

According to Table 4, the relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the interest in the consumption of the same food product (“Tomato paste B”) was statistically significant for 12.5% of the commercials (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

The relationship between recalling TV food commercials with being interested in consumption of the same food products among primary schoolchildren of Shirvan, May 10-11, 2015

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the content of TV programs for children in a period of 1 week. Compared with the studies conducted in previous decades, the duration of TV food commercials has decreased significantly.[15,16,17]

The decreasing trend can be seen in other recent studies in Iran.[1] This trend may somehow reflect the new policies of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) in reducing commercials directed at children. On the other hand, this study was conducted in a period that was close to the final examinations of schoolchildren in Iran (almost from May 9 to 21) and the time spent on watching TV probably decreased drastically. Furthermore, this trend might be due to an increase in tariffs of broadcasting of commercials. However, due to lack of convincing evidence, any more comment would be impossible on this matter.

In the current study, the frequency of snacks (plum paste and fruit leather, 75%), fruit juice (20%), and flavorings (tomato paste 5%) ranked first to third, respectively, in the food products group [Table 1]. The finding is in agreement with other studies,[19,20,21] indicating the dominance of displayed foods that are rich in salt and/or sugar. Despite the decline in the number of commercials related to foods during programs for children and adolescents, it seems that the contents of these messages are still nonnutritional and unhealthy.[22,23]

"High quality" and “good taste” were the dominant messages that promoted the sale of the food products. In an advertisement of leather fruit, a group of fruits was playing happily; while jumping from a spring, they changed into fruit leather and plum paste, implicitly conveying the message that these food products, which are processed using industrial methods, are as healthy and nutritious as natural fruits. These findings are almost in agreement with previous studies, in which “taste” and “high quality” were the most frequent messages used to promote the sale of food products.[24,25,26,27,28,29]

In the current study, “high quality/precision in preparation,” “novelty,” and “stimulation of thirst and hunger” were the most frequent appeals [Table 2]. These findings are almost consistent with the results of previous studies, but the rank of the appeals was different.[19,27] In similar studies conducted in other countries, “entertainment,” “adventure,” and “becoming successful” were mentioned among the most frequent appeals.[30] However, “stimulation of hunger and thirst” was the dominant appeal for TV food commercials targeted at children as avid consumers.[31]

While most similar studies have exclusively analyzed the content of TV commercials,[11,20,21] this study is one of the few studies to examine the behavior of consumers simultaneously. This study showed that in most of the cases, there was a significant relationship between recalling TV food commercials and the interested in the related food products [Table 3], and the interest in the consumption of the same food was significant for one food product (one out of eight or 12.5% of the food products) [Table 4]. The results are more or less similar in other studies. In one study, it was observed that watching TV is linked to some unhealthy eating behaviors such as decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables and increased consumption of fast foods in school-age children.[32] It was also observed that exposure to commercials for healthy foods could increase their consumption by preschoolers[7] and by contrast and exposure to commercials for unhealthy foods could increase their consumption among teenagers.[33] Many studies have also shown that more exposure to TV commercials affects food preferences and the demand for the advertised products in preschoolers and schoolchildren.[34,35,36,37]

The current research was a cross-sectional study, in which the content of TV food commercials and the attitude and behavior of the audience toward TV food commercials was evaluated simultaneously. It certainly cannot be concluded that the relationship found in the current study shows causality; however, consideration of the existing literature on TV food commercials and their effects on children as vulnerable audience[31] makes our findings worthy of note. More longitudinal studies are obviously needed on this issue.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared with other studies, the number of TV food commercials, at least in children's programs of IRIB, has decreased significantly. However, the small number of food commercials does not encourage healthy eating. Due to the high vulnerability of children and adolescents to TV food commercials, the authorities should pay more attention to this area. Regarding the observed significant relationship between recalling food commercials and the desire to consume them by children, the current study provides convincing evidence for policy-makers and researchers to take more proactive steps in improving the children's eating behaviors.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is supported by Students’ Research Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Movahhed T, Seifi S, Rashed Mohassel A, Dorri M, Khorakian F, Mohammadzadeh Z. Content analysis of Islamic Republic of Iran television food advertising related to oral health: Appeals and performance methods. J Res Health Sci. 2014;14:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayapushpam T, Maheshwar M, Rao DR. A comparative analysis of television food advertisements aimed at adults and children in India. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng. 2014;2:476–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly B, Halford JC, Boyland EJ, Chapman K, Bautista-Castaño I, Berg C, et al. Television food advertising to children: A global perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1730–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lioutas ED, Tzimitra-Kalogianni I. “I saw Santa drinking soda!” Advertising and children's food preferences. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41:424–33. doi: 10.1111/cch.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter OB, Patterson LJ, Donovan RJ, Ewing MT, Roberts CM. Children's understanding of the selling versus persuasive intent of junk food advertising: Implications for regulation. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:962–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holsten JE, Deatrick JA, Kumanyika S, Pinto-Martin J, Compher CW. Children's food choice process in the home environment. A qualitative descriptive study. Appetite. 2012;58:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicklas TA, Goh ET, Goodell LS, Acuff DS, Reiher R, Buday R, et al. Impact of commercials on food preferences of low-income, minority preschoolers. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9:221–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyland EJ, Harrold JA, Kirkham TC, Halford JC. Persuasive techniques used in television advertisements to market foods to UK children. Appetite. 2012;58:658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE. Television watching, energy intake, and obesity in US children: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:360–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guran T, Turan S, Akcay T, Degirmenci F, Avci O, Asan A, et al. Content analysis of food advertising in Turkish television. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:427–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motlagh ME, Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Majdzadeh R, Heidarzadeh A CASPIAN Study Group. Rationale, methods and first results of the Iranian national programme for prevention of chronic diseases from childhood: CASPIAN Study. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:302–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentile DA, Oberg C, Sherwood NE, Story M, Walsh DA, Hogan M. American Academy of Pediatrics. Well-child visits in the video age: Pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines for children's media use. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1235–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1121-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts SA. Models for assisted conception data with embryo-specific covariates. Stat Med. 2007;26:156–70. doi: 10.1002/sim.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esmi R, Saadipour E, Asadzadeh H. The relationship between watching TV commercials and consumption pattern of Tehran's children and adolescents. Quarterly Journal of Communication Research. 2010;17:93–117. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirzaei H, Amini S. Content analysis of television advertisements with an emphasis on social class and lifestyle. Quarterly of Iranian Association of Cultural and Communication Studies, Fall. 2006;2:135–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotz K, Story M. Food advertisements during children's Saturday morning television programming: Are they consistent with dietary recommendations? J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1296–300. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo J, Leung SS, Ho SC, Lam TH, Janus ED. A food frequency questionnaire for use in the Chinese population in Hong Kong: Description and examination of validity. Nutr Res. 1997;17:1633–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amini M, Omidvar N, Yeatman H, Shariat-Jafari S, Eslami-Amirabadi M, Zahedirad M. Content analysis of food advertising in Iranian children's television programs. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:1337–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mchiza ZJ, Temple NJ, Steyn NP, Abrahams Z, Clayford M. Content analysis of television food advertisements aimed at adults and children in South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:2213–20. doi: 10.1017/S136898001300205X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sukumaran A, Diwakar MP, Shastry SM. A content analysis of advertisements related to oral health in children's Tamil television channels – A preliminary report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:232–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coon KA, Tucker KL. Television and children's consumption patterns. A review of the literature. Minerva Pediatr. 2002;54:423–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chestnutt IG, Ashraf FJ. Television advertising of foodstuffs potentially detrimental to oral health - A content analysis and comparison of children's and primetime broadcasts. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Grasso D. What is television trying to make children swallow? Content analysis of the nutrition information in prime-time advertisements. J Nutr Educ. 2000;32:187–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wicks E. Right to receive treatment in accordance with the Human Rights Act 1998. Br J Nurs. 2009;18:1192–3. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.19.44829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren MD, Pont SJ, Barkin SL, Callahan ST, Caples TL, Carroll KN, et al. The effect of honey on nocturnal cough and sleep quality for children and their parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1149–53. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amini M, Kimiagar M, Omidvar N. Which foods do TV food advertisements entice our children to eat? Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2007;2:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folta SC, Goldberg JP, Economos C, Bell R, Meltzer R. Food advertising targeted at school-age children: A content analysis. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.04.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page RM, Brewster A. Emotional and rational product appeals in televised food advertisements for children: Analysis of commercials shown on US broadcast networks. J Child Health Care. 2007;11:323–40. doi: 10.1177/1367493507082758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis MK, Hill AJ. Food advertising on British children's television: A content analysis and experimental study with nine-year olds. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:206–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amini M, Mohsenian-Rad M, Kimiagar M, Omidvar N, Ghaffarpour M, Mehrabi Y. Advertising on Iranian children's television: A content analysis and an experimantsl study with junior high school students. Ecol Food Nutr. 2005;42:123–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipsky LM, Iannotti RJ. Associations of television viewing with eating behaviors in the 2009 health behaviour in school-aged children study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:465–72. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, Chapman K, Crawford D, Pratt IS, et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horgan KB, Choate M, Brownell KD. CA: Oaks; 2001. In: Singer DG, Singer JL, editors; pp. 447–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Story M, French S. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taras HL, Sallis JF, Patterson TL, Nader PR, Nelson JA. Television's influence on children's diet and physical activity. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;10:176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borzekowski DL, Robinson TN. The 30-second effect: An experiment revealing the impact of television commercials on food preferences of preschoolers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:42–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]