Abstract

Background:

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are known to cause occupational injuries. This study aimed to collate the existed relevant data and develop a general feature of MSDs problem among Iranian workforce.

Methods:

In this study, we used the raw data related to 8004 employees from 20 Iranian industrial settings distributed throughout the country. In all studies, participants were selected based on simple random sampling method, and the data were collected using demographic characteristics and Nordic MSDs questionnaires.

Results:

The most prevalent MSDs symptoms were reported in the lower back (48.9%), shoulders (45.9%), neck (44.2%), upper back (43.8%), and knees (43.8%). Prevalence rates of MSDs at least in one body region were found to be the highest (90.3%) among health-care workers. Prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in all body regions were higher among workers with dynamic activities as compared to those of workers with static activities.

Conclusions:

MSDs symptoms were common among the study population. Health-care provider and workers with dynamic activities had the highest rate of MSDs. These results merit attention in planning and implementing ergonomics interventional program in Iranian industrial settings.

Keywords: Injury, musculoskeletal system, occupational, risk factor, workplace

INTRODUCTION

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are identified as work-related diseases from the time of Ramazzini in the 18th century who described classical cases of such injuries in his book.[1] MSDs have had increasing trend around the world during the past decades. They cause work-related disability in workers with notable financial outcomes due to direct and indirect (i.e., restricted or lost working days) costs.[2] The economic loss of such disorders influences both individuals and organizations.[3] They are a global occupational ergonomics issue distributed in both industrialized and industrially developing countries.[4] In industrially developing countries, injuries in the workplace are very important problems.[4] Inappropriate working conditions and lack of an efficient occupational injury prevention program in these countries have resulted in high rates of MSDs among working groups.[5] Coury has pointed out that in spite of the fact that work-related MSDs (WMSDs) have had increasing trend in developing countries; research for WMSDs prevention seems insufficient.[6]

Musculoskeletal symptoms risk factors are work activities such as awkward and static postures, handling materials manually, repetitive movements[7] as well as individual, psychosocial, and organizational factors which known as important predictive variables.[8,9,10,11,12,13]

WMSDs prevention in the workplace requires identification of major individual and occupational risk factors associated with symptoms and elimination of the contributing factors from the working environment.[14] In Iran, regarding to the technologies and work practices commonly utilized in industries, employees are exposed to varieties of musculoskeletal risk factors such as manual heavy load handling, awkward working postures, improper workstation design, and lack of adequate work-rest cycle. In this situation, high rate of musculoskeletal symptoms occurrence is expected among the workforce.

To improve workers’ health and reduce economic loss due to WMSDs in Iranian industries, employees’ exposure to musculoskeletal injuries risk factors should be eliminated. Some separate studies have so far been conducted in different Iranian industries and job groups to determine musculoskeletal symptoms prevalence and to determine main factors related to symptoms of MSDs. In the present study, we aimed to collate the existed relevant data and develop a general feature of MSDs problem among Iranian workforce and job groups. It is believed that the result of this project can provide an appropriate base for identification of high-risk occupations and their prioritization for implementing ergonomics interventional programs in the Iranian workplace.

METHODS

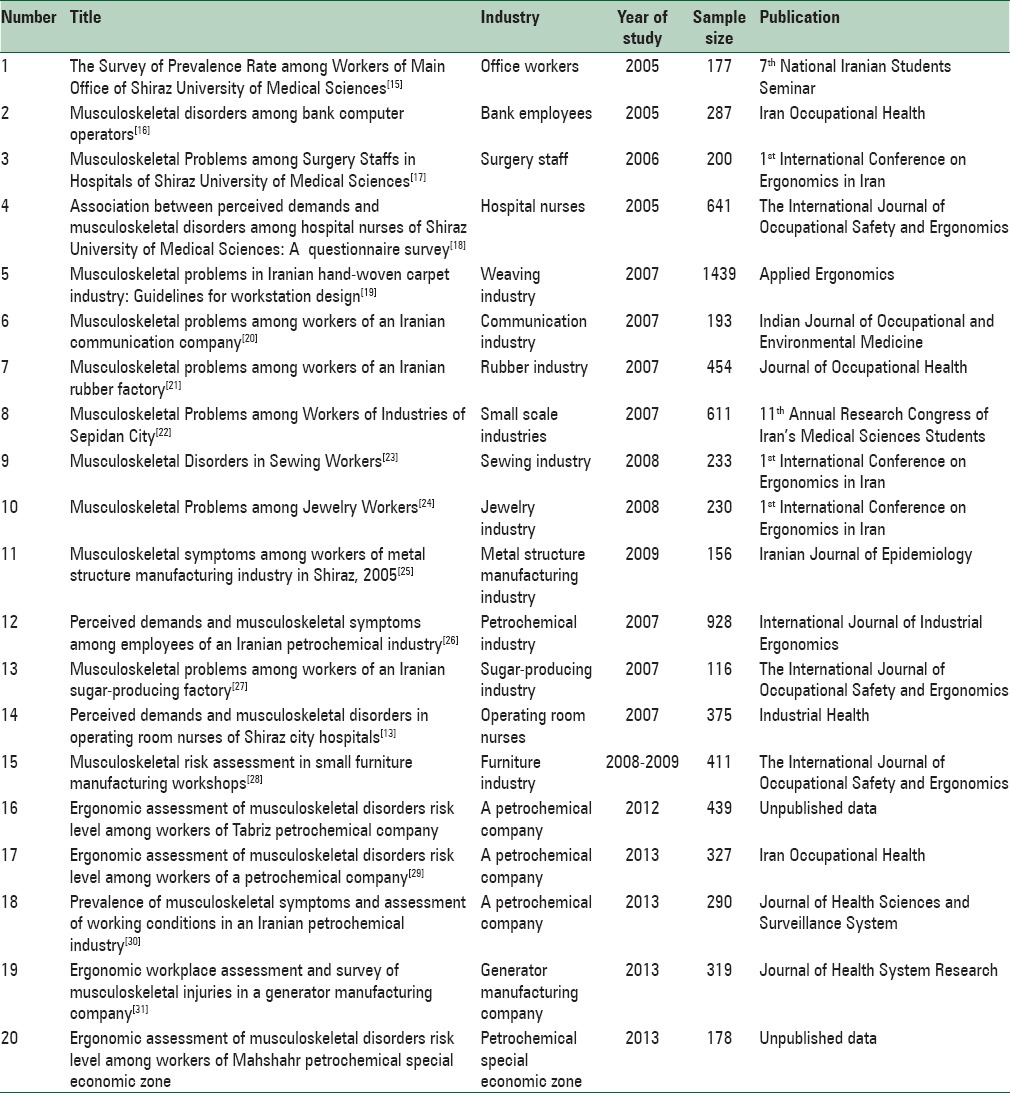

In this study, we used the raw data of our previous studies conducted in diverse Iranian industrial settings [Table 1]. Collectively, the data related to 8004 employees with at least 1 year of job tenure from 20 Iranian industries distributed throughout the country were analyzed. In all studies, participants were selected based on simple random sampling method. In all studies, the data-gathering tool was the same and consisted of an anonymous self-administered questionnaire with the two following parts:

Table 1.

Studies on musculoskeletal disorders among Iranian workers in different industries

Personal details including gender, age, weight, height, job tenure, daily working time (hours), marital status, type of job activities (static and/or dynamic), and working schedule

The general Nordic Questionnaire of Musculoskeletal symptoms (NMQ) to examine reported cases of MSDs among the study population.[32] The Persian version of NMQ validity and reliability was examined by Choobineh et al.[10] Reported MSDs symptoms were limited to the past 12 months.

In all studies, each participant received the questionnaire in person in her/his workplace.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 16 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). T-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and Chi-square test were used to assess univariate associations between independent variables and reported musculoskeletal symptoms.

RESULTS

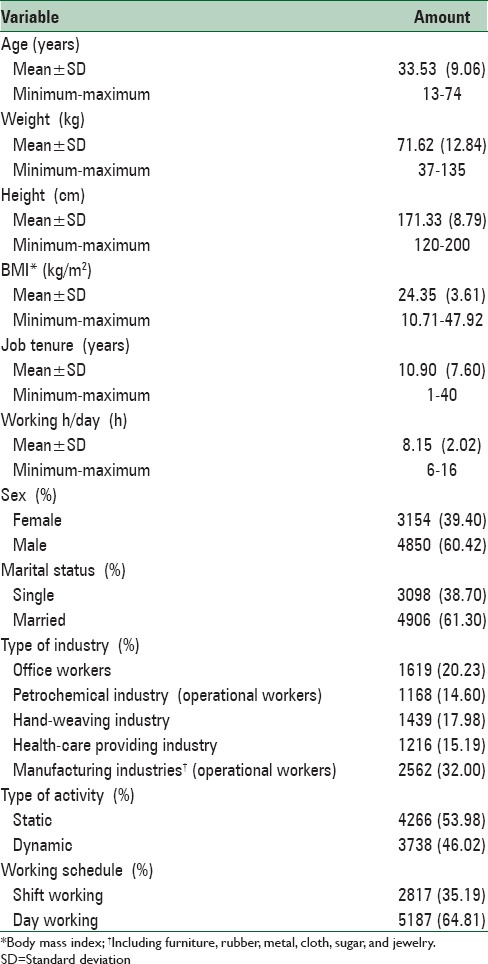

Table 2 shows personal characteristics of the participants.

Table 2.

Some personal details of the studied workers (n=8004)

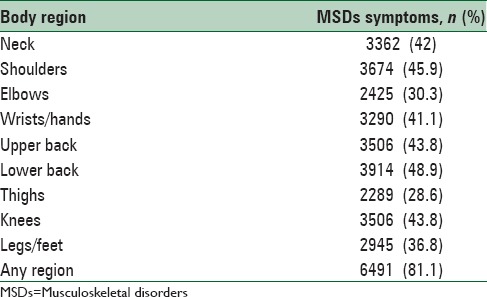

The results of NMQ showed that lower back (48.9%), shoulders (45.9%), neck (44.2%), upper back (43.8%), and knees (43.8%) symptoms had high prevalence among the participants [Table 3].

Table 3.

Frequency of reported musculoskeletal symptoms in different body regions among workers during the last 12 months (n=8004)

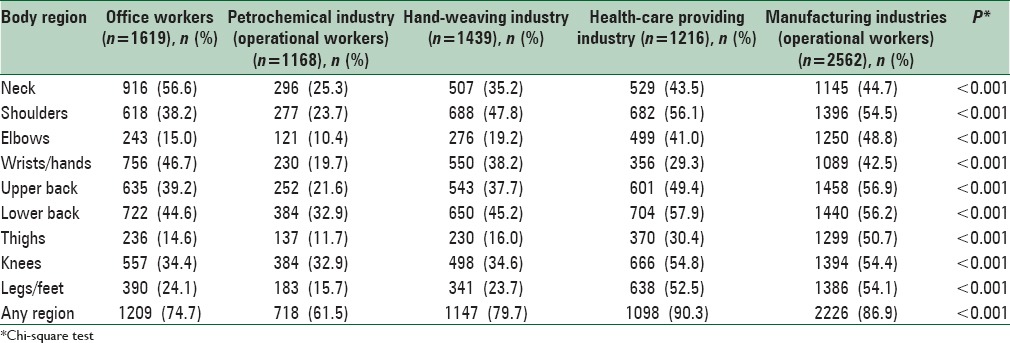

Table 4 presents prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in different body regions based on the type of industry. As displayed in this table, prevalence rates of MSDs at least in one body region are the highest among health-care workers (90.3%), followed by manufacturing (86.9%), hand-weaving (79.7%), office (74.7%), and petrochemical workers (61.5%), respectively. As shown, the prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in the neck (56.6%) and wrists/hands (46.7%) regions are higher among office workers as compared to those of workers in other industries. The prevalence rates of lower back (57.9%), shoulders (56.1%), and knees (54.8%) symptoms are higher among health-care workers as compared to those of other employees. Furthermore, the prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in the upper back (56.9%), legs/feet (54.1%), thighs (50.7%), and elbows (48.8%) regions are higher among manufacturing workers than those of other workers.

Table 4.

Prevalence rate of musculoskeletal disorders symptoms in different body regions based on the type of industry (n=8004)

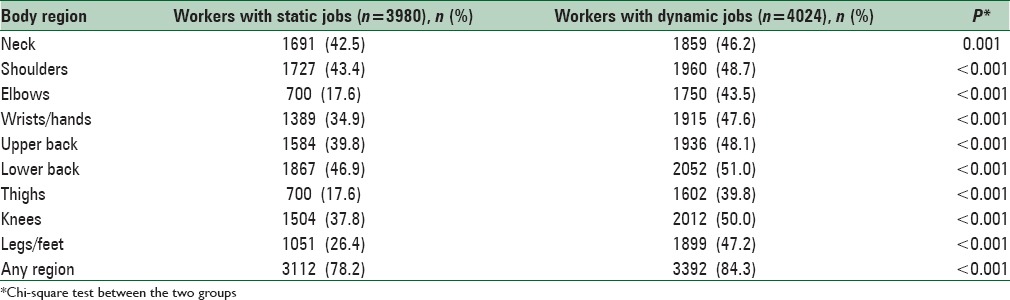

Table 5 demonstrates prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in different body regions based on type of activity (i.e., static and dynamic). As shown, the prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms in all body regions are higher among workers with dynamic activities as compared to those of other workers (workers with static activities).

Table 5.

Prevalence rate of musculoskeletal disorders symptoms in different body regions based on type of activity (n=8004)

DISCUSSION

The study population was relatively young with mean (standard deviation [SD]) age and mean (SD) job tenure of 33.53 (9.06) and 9.90 (7.41) years, respectively. The majority of the participants were male (53.6%) and married (61.3%).

The results obtained from NMQ revealed that musculoskeletal symptoms were common in the studied individuals. Symptoms in the lower back, shoulders, neck, upper back, and knees were prevalent problems in the participants. In the European Union, the average proportion of individuals reporting MSDs as their most serious work-related health problem was 54%, the lowest and the highest proportion were in Bulgaria (37%) and in Germany (75%), respectively (2012). Based on Farioli et al. study conducted among 43,816 European employees in 34 countries, the prevalence rate of MSDs in the back region ranged from 25.7% in Ireland to 63.8% in Portugal and prevalence rates of neck/upper limb symptoms ranged from 26.6% in Ireland to 67.7% in Finland.[33] The report of Health and Safety Executive on MSDs in Great Britain in 2014 revealed that back pain among studied workers was in the priority, followed by upper and lower limbs disorders. Interestingly, this report declared that prevalence rate of WMSDs had decreasing trend in 2013/2014 as compared to 2001/2002.[34] Kim and Nakata pointed out that in Korean and Japanese workers, the most reported WMSDs were related to the neck, shoulder, and upper limb regions.[35]

The results of the present study showed that the prevalence of MSDs symptoms at least in one body region among health-care workers had the highest rate in comparison to the workers of other industrial settings, while in the European countries, the most WMSDs occurrence was reported in construction industry.[36]

The results of the present study revealed that prevalence rates of MSDs symptoms among office workers in the neck and wrists/hands were higher than those of other employees. In some other studies, namely, Zungu and Ndaba,[37] Choobineh et al.,[31] and Tornqvist et al.,[38] similar results were reported.

The result of this study showed that prevalence rate of MSDs symptoms in the lower back, shoulders, and knees among health-care staff was higher than those of employees from other industries. This finding is in line with the results of other studies indicating that workers in the health-care industry are at higher risk of suffering from occupational MSDs.[39,40] Risk factors including patient transfer, extra force exertion, awkward and static posture, prolonged standing position, high mental workload, and working in shift schedule have been reported to be probable causes of the high prevalence of MSDs in this industry.[41]

Upper back, legs/feet, thighs, and elbows had high prevalence rate of MSDs among operational workers in manufacturing industries. Schierhout et al. in their study on manufacturing industry in South Africa pointed out that the low back, neck/shoulder, and forearm/wrist regions had high rate of symptoms.[42]

Prevalence rate of MSDs symptoms in all body regions was higher among workers with dynamic jobs (in dynamic jobs, mobility of workers is high, such as welders, mine workers, and so on) as compared to that of workers with static jobs (in static jobs, mobility of workers is low, such as office workers, bank employees, and so on). This finding indicated that eliminating MSDs risk factors among workers with dynamic jobs had high priority. It seems that risk factors such as lifting of heavy loads, repetitive movements, standing position for long period of time, and extra force exertion are causes of high prevalence rate of MSDs symptoms among workers with dynamic jobs.

Limitations

Regarding to the cross-sectional nature of the studies used in this paper and the method of self-report for data gathering, the results of the present study are to be cautiously interpreted. Self-report methodology has difficulty in remembering, deception, or denial. Furthermore, because the statistical analyses were limited to working employees, ones who had left their careers because of MSDs injuries might have been excluded from the study and healthy worker effect could occur. Thus, the symptoms prevalence rates may be underestimated.

We can somewhat generalize the results of our study to other places (such as office workplaces, petrochemical industry, hand-weaving industry, health-care providing industry, and manufacturing industries) that are more like to our study.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the present study revealed that symptoms from the musculoskeletal system were common among Iranian workers studied. The overwhelming percent of the individuals studied (81.1%) had some type of MSDs symptoms in the preceding 12 months. This indicates that the problem of MSDs among Iranian workers is an important issue and requires proper attention in national level.

The most symptoms were declared in the lower back, shoulders, neck, upper back, and knees. Hence, for improving conditions of workplace, risk factors of these regions should be considered with priority. Based on the results, from the viewpoint of type of industry, the highest prevalence rates of musculoskeletal symptoms were observed in health-care providing industry followed by manufacturing industries. It can, therefore, be pointed out that corrective ergonomics measures for eliminating or minimizing musculoskeletal injuries in national level should focus on these industries.

Furthermore, from the point of view of the type of activity, the prevalence rates of MSDs in all body regions were higher among workers with dynamic jobs as compared to those of workers with static jobs. It seems that risk factors such as lifting of heavy loads, repetitive movements, standing position for long period of time, and extra force exertion are causes of high prevalence rate of MSDs symptoms among workers with dynamic jobs.

Based on this finding, it could be concluded that reducing risk factors of MSDs in dynamic jobs should be considered with higher priority.

Financial support and sponsorship

The research funding for this study was partially provided by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all Iranian workers who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franco G. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A lesson from the past. Epidemiology. 2010;21:577–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e0c6f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, Protecting Workers’ Health Series No. 5, Preventing Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Workplace, 2003. 2015. [Last accessed on 2015 Dec 03]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/en/

- 3.Mohammadfam I, Kianfar A, Afsartala B. Assessment of musculoskeletal disorders in a manufacturing company using QEC and LUBA methods and comparison of results. Iran Occup Health. 2010;7:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bongers PM, Ijmker S, van den Heuvel S, Blatter BM. Epidemiology of work related neck and upper limb problems: Psychosocial and personal risk factors (part I) and effective interventions from a bio behavioural perspective (part II) J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:279–302. doi: 10.1007/s10926-006-9044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jafry T, O’Neill DH. The application of ergonomics in rural development: A review. Appl Ergon. 2000;31:263–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(99)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coury HJ. Time trends in ergonomic intervention research for improved musculoskeletal health and comfort in Latin America. Appl Ergon. 2005;36:249–52. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putz-Anderson V, Bernard BP, Burt SE, Cole LL, Fairfield-Estill C, Fine LJ, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piranveyseh P, Motamedzade M, Osatuke K, Mohammadfam I, Moghimbeigi A, Soltanzadeh A, et al. Association between psychosocial, organizational and personal factors and prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in office workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2016;22:267–73. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2015.1135568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milczarek M, Brun E, Houtman I, Goudswaard A, Evers M, Bovenkamp M, et al. Expert Forecast on Emerging Psychosocial Risks Related to Occupational Safety And Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choobineh A, Lahmi M, Shahnavaz H, Jazani RK, Hosseini M. Musculoskeletal symptoms as related to ergonomic factors in Iranian hand-woven carpet industry and general guidelines for workstation design. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2004;10:157–68. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2004.11076604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard N, Spielholz P, Bao S, Silverstein B, Fan ZJ. Reliability of an observational tool to assess the organization of work. Int J Ind Ergon. 2009;39:260–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsman P, Hanse JJ. The impact of decision latitude, psychological load and social support at work on the development of neck, shoulder and low back symptoms among female human service organization workers. Int J Ind Ergon. 2009;39:442–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choobineh A, Movahed M, Tabatabaie SH, Kumashiro M. Perceived demands and musculoskeletal disorders in operating room nurses of Shiraz city hospitals. Ind Health. 2010;48:74–84. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.48.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kezunović L, Stamatović S, Stamatović B, Jovanović J. One-year prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in aluminium industry potroom workers. Facta Univ (Ser Med Biol) 2004;11:148–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choobineh AR, Rajaei Fard AR, Akbari A, Miandashti R. The Survey of Prevalence Rate among Workers of Main Office of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. th National Iranian Students Seminar, Yasuj. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choobineh AR, Nouri E, Arjmandzadeh A, Mohamadbaigi A. Musculoskeletal disorders among bank computer operators. Iran Occup Health. 2006;3:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashani HA, Choobineh AR, Tabatabaee SH. Musculoskeletal Problems Among Surgery Staffs in Hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. st International Conference On Ergonomics in Iran, Tehra. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choobineh A, Rajaeefard A, Neghab M. Association between perceived demands and musculoskeletal disorders among hospital nurses of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences: A questionnaire survey. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2006;12:409–16. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2006.11076699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choobineh A, Hosseini M, Lahmi M, Khani Jazani R, Shahnavaz H. Musculoskeletal problems in Iranian hand-woven carpet industry: Guidelines for workstation design. Appl Ergon. 2007;38:617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choobineh A, Tabatabaei SH, Tozihian M, Ghadami F. Musculoskeletal problems among workers of an Iranian communication company. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2007;11:32–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.32462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choobineh A, Tabatabaei SH, Mokhtarzadeh A, Salehi M. Musculoskeletal problems among workers of an Iranian rubber factory. J Occup Health. 2007;49:418–23. doi: 10.1539/joh.49.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choobineh AR, Tabatabaee SH, Amiri R, Ghandi B. Musculoskeletal Problems among Workers of Industries of Sepidan City. 11th Annual Research Congress of Iran's Medical Sciences Students, Bandar Abbas. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kashani HA, Daneshvar S, Choobineh AR, Tabatabaee SH. Musculoskeletal Disorders in Sewing Workers. 1st International Conference On Ergonomics in Iran, Tehra. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aliyari L, Choobineh AR, Tabatabaee SH. Musculoskeletal Problems among Jewelry Workers. 1st International Conference On Ergonomics in Iran, Tehra. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choobineh AR, Solaymani E, Mohammad Beigi A. Musculoskeletal symptoms among workers of metal structure manufacturing industry in Shiraz, 2005. Iran J Epidemiol. 2009;5:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choobineh AR, Sani GP, Rohani MS, Pour MG, Neghab M. Perceived demands and musculoskeletal symptoms among employees of an Iranian petrochemical industry. Int J Ind Ergon. 2009;39:766–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choobineh A, Tabatabaee SH, Behzadi M. Musculoskeletal problems among workers of an Iranian sugar-producing factory. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2009;15:419–24. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2009.11076820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashemi Nejad N, Choobineh A, Rahimifard H, Haidari HR, Tabatabaei SH. Musculoskeletal risk assessment in small furniture manufacturing workshops. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2013;19:275–84. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2013.11076985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choobineh AR, Daneshmandi H, Fallahpoor A, Fard HR. Ergonomic assessment of musculoskeletal disorders risk level among workers of a petrochemical company. Iran Occup Health. 2013;10:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choobineh AR, Daneshmandi H, Asadi S, Ahmadi S. Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms and assessment of working conditions in an Iranian petrochemical industry. J Health Sci Surveill Syst. 2013;1:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choobineh AR, Daneshmandi H, Deilami F, Khoshnami S. Ergonomic workplace assessment and survey of musculoskeletal injuries in a generator manufacturing company. J Health Syst Res. 2013;9:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sørensen F, Andersson G, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987;18:233–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farioli A, Mattioli S, Quaglieri A, Curti S, Violante FS, Coggon D. Musculoskeletal pain in Europe: The role of personal, occupational, and social risk factors. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:36–46. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Musculoskeletal Disorders in Great Britain. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 25]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/

- 35.Kim EA, Nakata M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korea and Japan: A comparative description. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2014;26:17. doi: 10.1186/2052-4374-26-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveillance and Information Network. Musculoskeletal Health in Europe: Report V 5.0. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zungu L, Ndaba EF. Self-reported musculoskeletal disorders among office workers in a private hospital in South Africa: Prevalence and relation to physicla demands of the work. Occup Health South Afr. 2009;9:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tornqvist EW, Hagberg M, Hagman M, Risberg EH, Toomingas A. The influence of working conditions and individual factors on the incidence of neck and upper limb symptoms among professional computer users. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82:689–702. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daraiseh N, Cronin S, Davis L, Shell R, Karwowski W. Low back symptoms among hospital nurses, associations to individual factors and pain in multiple body regions. Int J Ind Ergon. 2010;40:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedge A, James T, Pavlovic-Veselinovic S. Ergonomics concerns and the impact of healthcare information technology. Int J Ind Ergon. 2011;41:345–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waters T, Collins J, Galinsky T, Caruso C. NIOSH research efforts to prevent musculoskeletal disorders in the healthcare industry. Orthop Nurs. 2006;25:380–9. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200611000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schierhout GH, Myers JE, Bridger RS. Musculoskeletal pain and workplace ergonomic stressors in manufacturing industry in South Africa. Int J Ind Ergon. 1993;12:3–11. [Google Scholar]