Abstract

Actin-associated proteins regulate multiple cellular processes, including proliferation and differentiation, but the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes are unclear. Here, we report that the actin-binding protein filamin A (FlnA) physically interacts with the actin-nucleating protein formin 2 (Fmn2). Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impairs proliferation, thereby generating multiple embryonic phenotypes, including microcephaly. FlnA interacts with the Wnt co-receptor Lrp6. Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impairs Lrp6 endocytosis, downstream Gsk3β activity, and β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus. The proliferative defect in Flna and Fmn2 null neural progenitors is rescued by inhibiting Gsk3β activity. Our findings thus reveal a novel mechanism whereby actin-associated proteins regulate proliferation by mediating the endocytosis and transportation of components in the canonical Wnt pathway. Moreover, the Fmn2-dependent signaling in this pathway parallels that seen in the non-canonical Wnt-dependent regulation of planar cell polarity through the Formin homology protein Daam. These studies provide evidence for integration of actin-associated processes in directing neuroepithelial proliferation.

KEY WORDS: Neural progenitor, Endocytosis, Filamin, Formin, Lrp6, Proliferation, Differentiation, Vesicle trafficking

Summary: Loss of filamin and formin causes multiple developmental defects, highlighting roles for these two proteins in Wnt signaling, Lrp6 endocytosis, Gsk3 activation and target gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

The actin cytoskeleton has primarily been implicated in the non-canonical Wnt pathway during development (Skoglund and Keller, 2010). In this pathway, Wnt protein binding to Frizzled (Fz) receptor leads to the recruitment of Dishevelled (Dvl), which forms a complex with the Formin homology protein Daam1. Daam1 activates a small Rho GTPase, which in turn promotes activation of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), a major effector of actin modification. Actin cytoskeletal changes through Daam1 mediate planar cell polarity (PCP) (Sato et al., 2006). PCP signaling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation, and therefore mediates development of the neuroepithelial lining along the lateral ventricles of the brain (Ciruna et al., 2006).

The Wnt signaling cascade also regulates neural proliferation during development, but does so through the canonical pathway (Kim et al., 2013). Wnt protein binds Fz and co-receptor Lrp5/6, a receptor tyrosine kinase. Activation promotes the cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin and inhibits its degradation through a destruction complex that includes glycogen synthase 3 (Gsk3). Some reports have suggested that Rac mediates β-catenin nuclear localization (Fanto et al., 2000). However, no formal mechanism for involvement of the actin cytoskeleton in the regulation of this pathway has been demonstrated.

Filamins are actin-binding proteins that generally serve as scaffolds to stabilize various proteins on the membrane through interactions with actin filaments (Gorlin et al., 1990). Filamin A (FlnA) regulates neural progenitor proliferation (Lian et al., 2012). Here, we report that FlnA physically interacts with formin 2 (Fmn2). Formins are a group of proteins involved in the polymerization of actin and associate with the fast-growing (barbed) end of actin filaments (Bogdan et al., 2014; Dettenhofer et al., 2008). Dual loss of FlnA and Fmn2 function leads to smaller brains and reduced neural proliferation and differentiation compared with loss of either protein alone. FlnA binds low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (Lrp6), and regulates both Lrp6 and Fmn2 localization to the cell membrane. Functional loss of FlnA and Fmn2 together impairs Lrp6 endocytosis and subsequent canonical Wnt pathway activation through Lrp6 phosphorylation-dependent Gsk3 inactivation. Diminished Gsk3 inactivation impedes β-catenin activation and accumulation in the nucleus, leading to impaired proliferation. Gsk3 inhibition is able to rescue the neural proliferation defect. Prior work has shown that the non-canonical Wnt pathway mediates PCP and proliferation through the Formin homology related protein Daam1, Rho GTPase and profilin (Ju et al., 2010; Sato et al., 2006). These findings now implicate a parallel pathway of actin-dependent regulation of the canonical Wnt pathway through Fmn2 and FlnA.

RESULTS

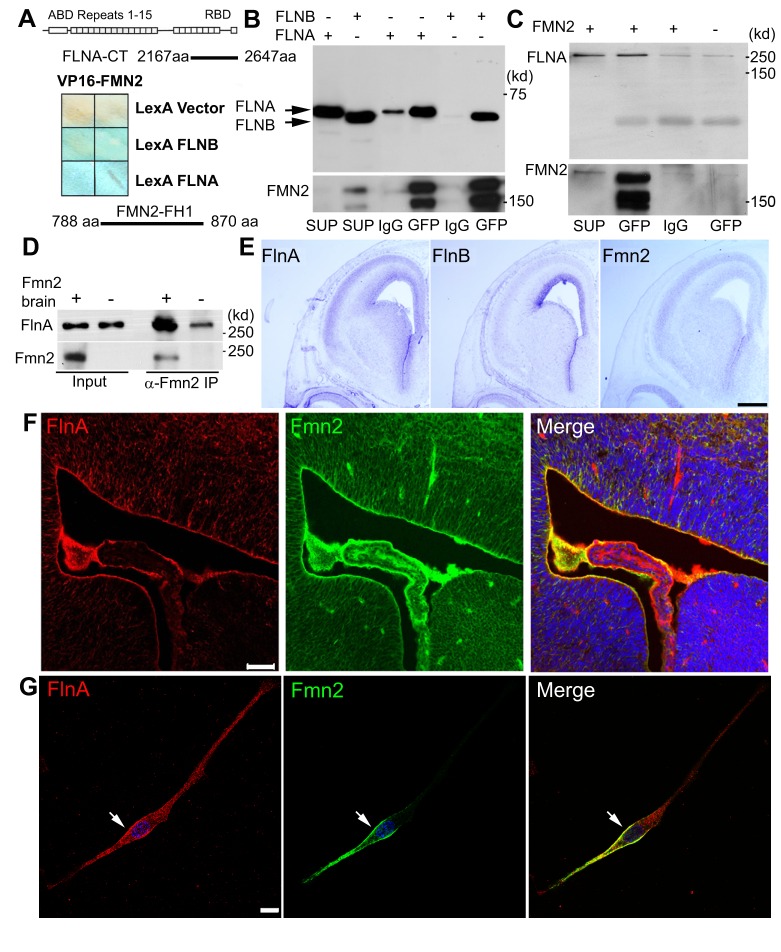

FlnA physically interacts and colocalizes with Fmn2 along the lipid membrane

Our prior studies have shown that FlnA regulates neural progenitor proliferation (Lian et al., 2012), but the upstream signaling pathway that regulates this process is not known. To identify molecules that might interact with FlnA, we used a human FLNA C-terminal fragment (amino acids 2167 to 2647) as bait to screen for FLNA binding partners by yeast two-hybrid assay, and found that Fmn2 binds to FLNA through its FH1 domain (amino acids 788 to 870) (Fig. 1A). Co-immunoprecipitation assays further showed that Fmn2-GFP pulled down both the C-terminus of FLNA (Fig. 1B) and endogenous full-length FLNA (Fig. 1C), while immunoprecipitation using wild-type (WT) and Fmn2 null mouse brain lysates confirmed physiological interactions between these proteins (Fig. 1D). In situ hybridization and immunostaining revealed overlapping FlnA and Fmn2 expression in developing embryonic day (E) 16 murine brain, especially in the ventricular zone, at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1E,F). In neural progenitors, FlnA and Fmn2 overlapped at the trailing edge of the cytoplasmic membrane and in vesicles (Fig. 1G, Fig. S1A), indicating that FlnA and Fmn2 might participate in membrane-associated protein transportation.

Fig. 1.

Filamin A (FlnA) interacts and overlaps with formin 2 (Fmn2) in developing mouse brain and neural cells. (A) FlnA directly interacts with Fmn2, as assessed by yeast two-hybrid assay. Filter assay demonstrates activation of lacZ reporter gene following binding of VP16-Fmn2 to LexA FLNA/B. DNA sequencing of the prey bound to FLNA/B identified the Fmn2 FH1 domain (amino acids 788-870) as the FLNA/B-interacting region. ABD, actin-binding domain; RBD, receptor-binding domain. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation shows that full-length Fmn2-GFP precipitates FLNA/B C-terminal fragments when a Fmn2-GFP construct is overexpressed with FLNA-C and FLNB-C constructs in HEK 293 cells. SUP, input supernatant; IgG, sample precipitated by normal IgG; GFP, sample precipitated by anti-GFP. (C) Endogenous FLNA is co-immunoprecipitated by full-length Fmn2-GFP using anti-GFP antibody in HEK 293 cells. (D) Endogenous FlnA is strongly co-immunoprecipitated from neonatal WT mouse lysates by anti-Fmn2 antibody. (E) Brightfield light microscopy of coronal E16 mouse brains shows overlapping mRNA expression of Flna, Flnb and Fmn2 by in situ hybridization. Flna and Fmn2 show strong and nearly identical expression patterns along the ventricular zone and within the cortical plate. (F) Fluorescent photomicrographs along the lateral ventricles of E16 Fmn2-GFP transgenic mouse embryos demonstrate that FlnA and Fmn2 share overlapping expression along the ventricular zone at the protein level. (G) Cultured neural progenitor cells expressing Fmn2-GFP, showing that Fmn2 overlaps with FlnA along the cytoplasmic membrane (arrow). Scale bars: 500 μm in E; 50 μm in F; 10 μm in G.

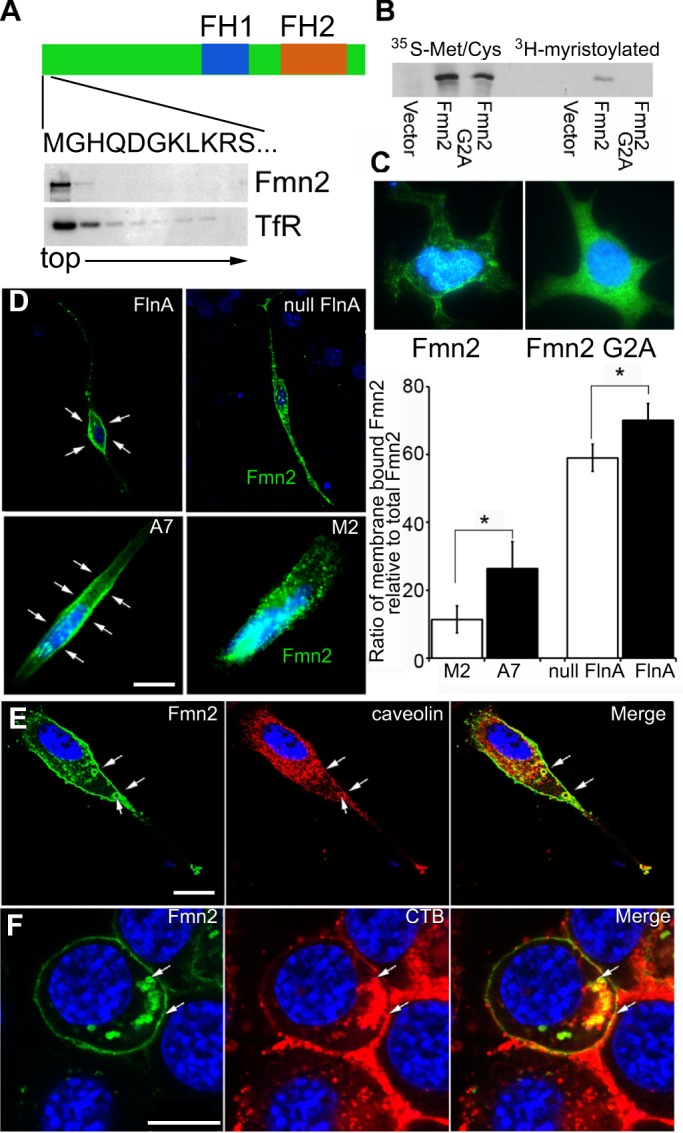

Similar to other members of the Formin family, Fmn2 contains a conserved proline-rich domain (FH1) and an actin-nucleating domain (FH2) (Fig. 2A). Although Fmn2 nucleates actin, not much is known about its actual function. Predictions for post-translational modification showed that Fmn2 is potentially myristoylated at the second amino acid, glycine. Myristoylation might mediate Fmn2 distribution into cellular lipid-rich components, including vesicles. Fmn2 association with membranes was initially tested using a membrane flotation assay of cell lysates. Examination of sucrose gradient cellular components showed that Fmn2 co-sedimented to the top of the flotation gradient with the transferrin receptor, a known membrane-associated protein (Fig. 2A). To further confirm Fmn2 myristoylation, we transfected empty vector, WT Fmn2 and mutant Fmn2(G2A) constructs into HEK 293 cells and labeled Fmn2 protein with 35S-methonine/cysteine and 3H-myristoylate. Immunoprecipitation assays showed that WT Fmn2 was indeed myristoylated, whereas Fmn2(G2A) was not (Fig. 2B). To examine the functional consequence of this myristoylation, WT and mutant Fmn2 constructs were transiently transfected into HEK 293 cells. Fmn2 was distributed along cell membranes, whereas Fmn2(G2A) remained dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2C). These observations suggested that myristoylation is vital to its anchorage onto lipid-rich membranes.

Fig. 2.

Fmn2 is involved in lipid-associated protein endocytosis. (A) Fmn2 is a lipid-associated protein. Sucrose density gradient centrifugation of Fmn2-expressing cell lysates shows that Fmn2 is present in the low-density (top) fractions, where lipid and lipid-binding proteins are enriched. As shown in the schematic, full-length Fmn2 contains a proline-rich FH1 domain, an actin-nucleating FH2 domain and an N-terminal sequence containing a putative myristoylation site at the second amino acid (glycine, G). TfR, transferrin receptor. (B) Fmn2 can be myristoylated at the second amino acid. Myristoylation was detected in WT Fmn2 but not in mutant (G2A) Fmn2 samples as assessed by labeling with 35S-methonine and 3H-myristolate acid and western blot. (C) Myristoylation assists in Fmn2 localization to lipid cell membranes. Loss of the myristoylation site led to the redistribution of Fmn2 from the lipid membranes to the cytosol in neural cells expressing WT and mutant (G2A) Fmn2-GFP. (D) FlnA expression affects Fmn2 localization along lipid cell membranes. Fmn2-GFP was transiently (5 h) expressed in WT and Flna null neural progenitors. Fluorescent photomicrographs show that Fmn2 was mainly localized to the cytoplasmic membrane (arrows) of FlnA-expressing cells but its expression transitions to cytoplasmic vesicles in Flna null cells. A similar pattern of staining is seen in FLNA-repleted A7 and FLNA-depleted M2 melanoma cells. These findings are quantified in the bar chart to the right. *P<0.05, two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.d. (E) Fmn2-expressing MEF cells show that Fmn2 colocalizes with caveolin, a caveolar marker, along the cell membrane and in circular vesicles (arrows). (F) Fmn2 expression also overlaps with endosomes of cholera toxin B (CTB), a marker for lipid rafts. The arrows indicate overlapping Fmn2 and CTB expression in endocytosed vesicles and on the cell membrane. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue) in all images. Scale bars: 10 μm in D-F.

Consistent with FlnA-Fmn2 binding, we observed that Fmn2 location is dependent on FlnA expression. Fmn2 strongly colocalized with the cytoplasmic membranes of FlnA-expressing neural progenitors and A7 FLNA-repleted melanoma cells, but was redistributed to cytoplasmic vesicles in Flna null neural progenitors and M2 FLNA-depleted melanoma cells (Fig. 2D). Given that FlnA was previously reported to associate with caveolin lipid raft vesicles (Sverdlov et al., 2009), we examined whether Fmn2 also colocalized with caveolin and the lipid raft marker cholera toxin B (CTB). Immunostaining showed that Fmn2 was highly colocalized with caveolin and CTB at cytoplasmic membranes and circular vesicles (Fig. 2E,F). Similar staining patterns were seen with neural progenitors, melanoma and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells, implying that Fmn2, together with FlnA and caveolin, might be involved in membrane-associated protein transport.

Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 function causes microcephaly and impairs neural progenitor proliferation

To understand the functional significance of FlnA and Fmn2 in vivo, we generated mice null for Fmn2 and double knockouts (Flna+Fmn2 null) (Fig. S1B-D, Fig. S2A-C). Loss of Fmn2 alone did not cause an overt defect in morphology (Fig. S1B-D). Compared with age-matched Flna (Dilp2) null male embryos, however, the double-knockout embryos showed earlier lethality prior to E16 (Lian et al., 2012). In addition, the brain size was significantly reduced both in rostral-caudal extent and in the width of the cortical plate relative to those of WT and Flna null brains (Fig. S2D,E), indicating that loss of Fmn2 in Flna null embryos causes a more severe microcephaly. Thus, Fmn2 synergistically affects FlnA function, given the worsening of Flna null-associated phenotypes.

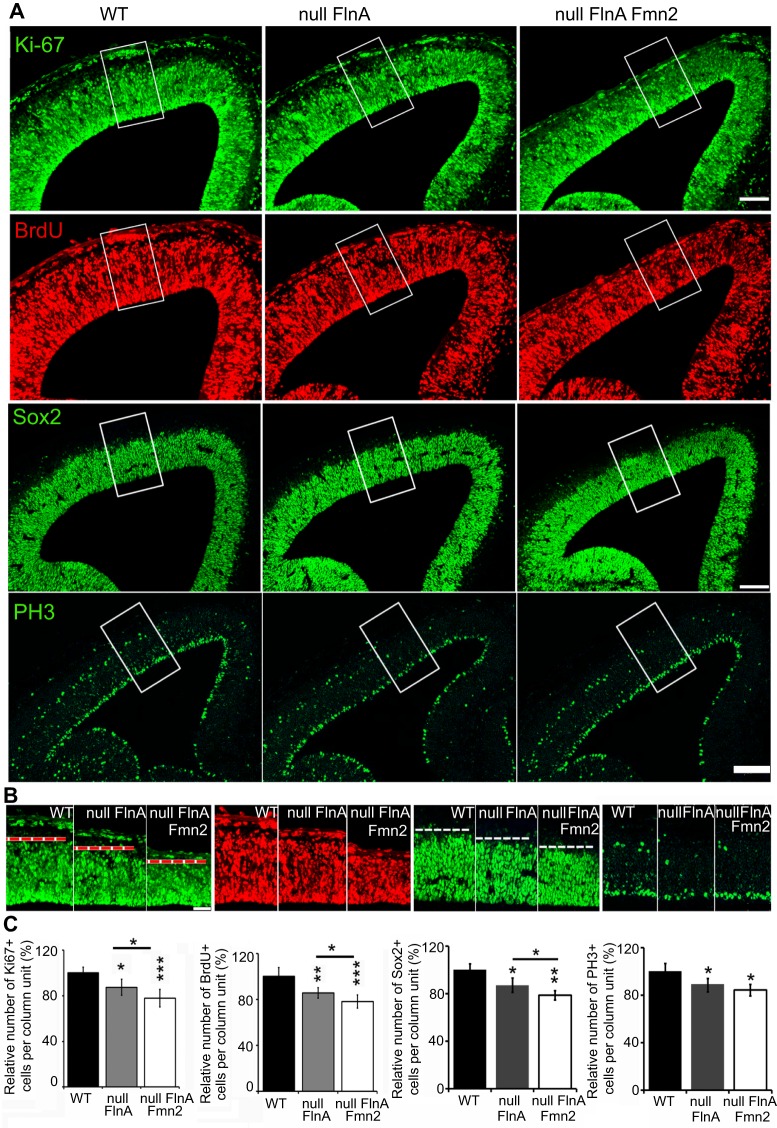

Microcephaly can be due to reduced cell proliferation and differentiation and/or increased apoptosis. Immunostaining on E13.5 mouse cortical sections for the apoptotic marker caspase 3 showed no change in the number of apoptotic cells in control versus Flna+Fmn2 null cortices (Fig. S3A,D). Loss of both FlnA and Fmn2 impaired cell proliferation, as staining for various proliferative or neural progenitor markers (Ki67, BrdU, Sox2 and phosphohistone H3) showed that the percentage of proliferating cells in E13.5 Flna+Fmn2 null cerebral cortices was decreased by ∼20-22% and ∼5-9% compared with WT and Flna null brains, respectively (Fig. 3A-C). Similar results were obtained following isolation and culture of neural progenitors from the double-null mice (Fig. S3B,D). Collectively, our data showed that loss of FlnA and Fmn2 did not increase cell death. Rather, a reduction in neural progenitor proliferation led to the observed microcephaly.

Fig. 3.

Flna+Fmn2 null cortex displays a defect in neural progenitor proliferation. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of E13.5 mouse cortex after immunostaining for the proliferation markers Ki67 (cell cycle) and BrdU (S phase), showing a significant reduction in the cortical width of the Ki67+ or BrdU+ cell layers in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex, as compared with littermate WT or Flna null cortex. Immunostaining for the neural progenitor marker Sox2 and M-phase marker phospho-histone H3 (PH3) further shows a reduction in neural progenitor number in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex. These results are consistent with impaired proliferation. (B) Higher magnification of the boxed regions in A demonstrate a reduction in the number of cells labeled by the various proliferative markers in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex. The red or white dashed line indicates the thickness of proliferating neural progenitors. (C) Statistical analyses (n≥3 independent samples per experiment) show that the number of cells per unit column labeled for Ki67 or BrdU in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex is decreased by ∼8% and ∼20% compared with Flna null and WT littermate controls, respectively. The numbers of Sox2+ or PH3+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex are decreased by 8% and 21%, or 4% and 16%, respectively, compared with Flna null and WT controls. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.d. Scale bars: 100 μm in A; 50 μm in B.

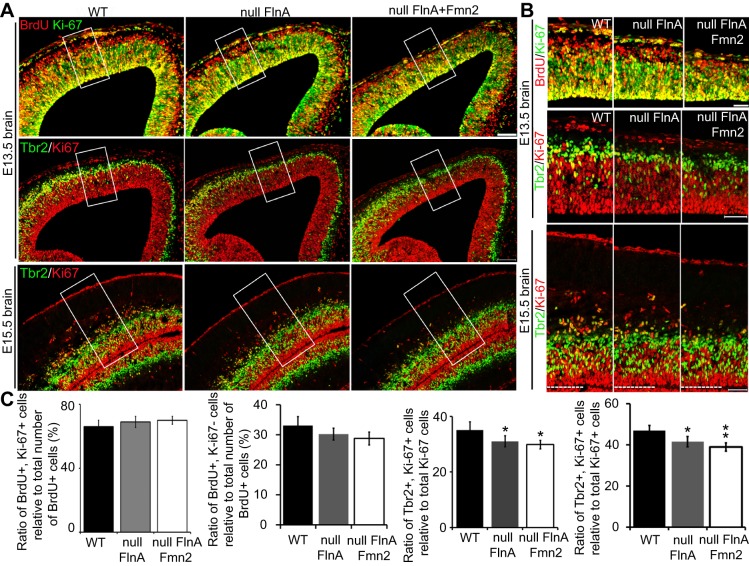

Either premature differentiation or a delay in the differentiation of progenitors can cause impaired proliferation rates. To identify whether a change in cell fate specification caused the Flna+Fmn2 null brain phenotype, we quantified the fraction of neural progenitors exiting the cell cycle by co-staining for BrdU and Ki67. BrdU+ Ki67− cells would capture the BrdU+ population that exited the cell cycle, whereas BrdU+ Ki67+ cells would reflect the fraction of proliferating BrdU+ progenitors that had remained in the cell cycle. We observed a trend whereby more neural progenitors in E13.5 Flna+Fmn2 null cortices remained in the cell cycle compared with those in WT and Flna null brains (Fig. 4A-C). As the BrdU+ Ki67+ cells would capture both intermediate and early progenitors, we co-stained for Ki67 and Tbr2 (also known as Eomes; an intermediate progenitor marker) on littermate brains. Co-staining with Ki67 and Tbr2 antibodies showed that the fraction of Ki67+ Tbr2+ differentiating progenitors (relative to total Ki67+ cells) was significantly lower in E13.5 Flna+Fmn2 null than in WT cortices. A similar trend was seen upon comparison of Flna+Fmn2 versus Flna null cortices (Fig. 4A,B, middle rows; Fig. 4C, third bar chart). By E15.5, more early progenitors (Trb2− Ki67+) are observed in Flna+Fmn2 as compared with Flna null mice (Fig. 4A-C), suggesting that a greater proportion of neural progenitors in Flna+Fmn2 null brains adopted early, as opposed to intermediate, progenitor cell fates, and hence led to delayed differentiation or a generalized growth retardation.

Fig. 4.

Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 decreases the differentiation of neural progenitors. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs showing that the fraction of cells exiting (BrdU+ Ki67−) or remaining (BrdU+ Ki67+) in the cell cycle relative to the total number of BrdU+ cells is not significantly different between WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null E13.5 embryos. Co-staining for Tbr2 and Ki67 shows a smaller fraction of Tbr2+ Ki67+ cells in E13.5 and E15.5 Flna+Fmn2 null as compared with littermate WT and Flna null cortices, suggesting that a smaller fraction of Ki67+ cells in the Flna+Fmn2 null cortex adopt a differentiating cell fate. (B) Higher magnification of the boxed regions in A showing colocalization of Ki67 with BrdU or Tbr2. (C) Statistical analyses (n≥3 independent samples per experiment) shows no significant difference in the fractions of BrdU+ Ki67+ cells and BrdU+ Ki67− cells between WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null cortices, although there was a trend toward more cells remaining in the cell cycle (BrdU+ Ki67+) in the Flna+Fmn2 null embryos. Tbr2+ Ki67+ cell quantification shows that a smaller fraction (∼30%) of Ki67+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex adopted a differentiating cell fate compared with those (36% and 32%) in WT and Flna null cortices, respectively. The difference in the fraction of Ki67+ BrdU+ cells between WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null E15.5 cortices is more evident (47%, 41% and 38%, respectively). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.d. Scale bars: 100 μm in A; 50 μm in B.

A delay in differentiation or growth retardation would lead to reduced neurogenesis. We therefore used several age-specific neural and neuronal markers to examine changes in differentiation in the cortices of double-null mice: Tbr2, Ctip2 (also known as Bcl11b; layer V and VI neurons), Tbr1 (subplate and layer VI neurons) and Tuj1 (also known as Tubb3; an early neuronal marker). Since Flna+Fmn2 null embryos survive prior to E16, we quantified the expression of these markers in E15.5 brains. Cortical thickness and the number of positively stained cells in a column unit for Tbr2, Ctip2, Tbr1 and Tuj1 immunostaining were all reduced in Flna+Fmn2 null cortices compared with WT and Flna null cortices (Fig. S4A-C, Fig. S5A-C). Co-staining for Tbr1 and Ctip2 also showed that fewer Ctip2+ Tbr1− cells were present in Flna+Fmn2 null cortices compared with WT and Flna null cortices (Fig. S5A-C), suggesting a delay in cell differentiation. Lastly, co-staining of Flna+Fmn2 null cultures with anti-BrdU and anti-cyclin D1 (Ccnd1, a G1 phase marker) antibodies showed that cell cycle progression from S to G1 phase in Flna+Fmn2 null cells was significantly slower than in WT cells (Fig. S3B,D), but did not differ from that seen in Flna null cells. Moreover, the G2/M to G1 phase progression in Flna+Fmn2 null cells was significantly impaired compared with WT and Flna null cells (Fig. S3C,D, right panel), as determined by flow cytometry, suggesting that loss of FlnA and Fmn2 together further impaired M phase progression.

Overall, these findings indicate that loss of Fmn2 led to a synergistic effect on FlnA-dependent cell proliferation and differentiation, leading to reduced proliferation and delayed differentiation due to prolongation of the cell cycle.

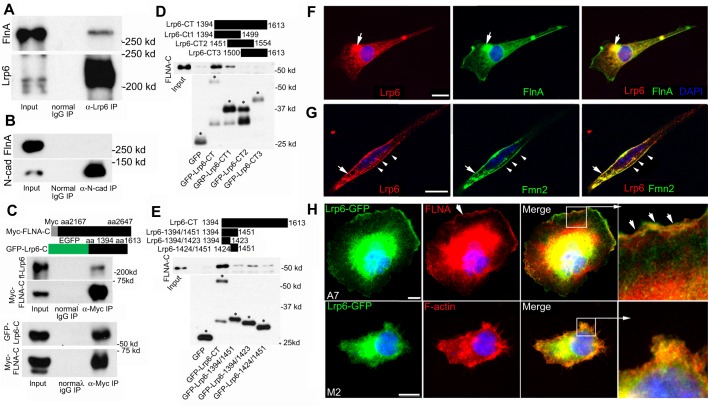

FlnA physically interacts with Lrp6 and stabilizes its localization along the cell membrane

Formins (i.e. Daam1) have been implicated in the non-canonical Wnt pathway, suggesting that Fmn2 might participate in the regulation of signaling pathways for these morphogens/mitogens in concert with FlnA. Moreover, mice null for the Wnt co-receptor Lrp6 share many of the features seen with the Flna+Fmn2 knockout mice (Pinson et al., 2000). Therefore, further experiments focused on the involvement of Fmn2 and FlnA in the Wnt signaling pathway are necessary.

First, the human FLNA C-terminal fragment (amino acids 2167-2647) could be co-immunoprecipitated by dishevelled 2 (Dvl2) (Fig. S6A), a component of the Wnt canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. As controls, the Formin family proteins Daam1 and mDia3 (Diaph2) (Fig. S6B,C), as well as dishevelled 1 (Dvl1) (data not shown), were all unable to precipitate FlnA, suggesting specificity of the interaction between FlnA and Dvl2. Second, given that proliferative changes primarily implicate a canonical Wnt pathway and the similarities between the Lrp6 null and Flna+Fmn2 null mice (Pinson et al., 2000), we next asked whether FlnA interacts with Lrp6 to stabilize and promote interactions between the Wnt proteins. Endogenous full-length FlnA was found to form a complex with endogenous full-length Lrp6 in E13.5 brain lysate by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A), whereas control N-cadherin (a cell surface adhesion molecule also implicated in neural proliferation) did not precipitate full-length FlnA (Fig. 5B). Conversely, the C-terminal region of Lrp6 and full-length Lrp6 could be reciprocally immunoprecipitated by the C-terminal receptor-binding region of FlnA (Fig. 5C). To further map the specific FlnA binding sites to the Lrp6 intracellular C-terminus, we constructed three C-terminal fragments, each fused to GFP. Both the full-length Lrp6 C-terminal fragment and Lrp6-CT1 (amino acids 1394-1499) could specifically pull down FlnA, whereas Lrp6-CT2 (amino acids 1451-1554) and Lrp6-CT3 (amino acids 1500-1613) could not (Fig. 5D), suggesting that the FlnA binding site was localized to amino acids 1394-1450 of Lrp6. Further refining this binding interaction, we constructed two additional Lrp6 subdomains (amino acids 1394-1423 and 1424-1451), with preferential interaction recorded with the 1394-1423 amino acid fragment (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

FlnA and Fmn2 interact and overlap with components of the Wnt signaling pathway. (A) Endogenous Lrp6 interacts with endogenous FlnA. Co-immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating E13.5 brain lysates with normal IgG and anti-Lrp6 antibody. (B) Control N-cadherin could not precipitate FlnA under the same condition as in A. (C) Conversely, myc-tagged FLNA C-terminus immunoprecipitated both full-length Lrp6 (upper panel) and its GFP-tagged C-terminus (lower panel). Schematics illustrate the myc-fused FLNA C-terminus and GFP-fused Lrp6 C-terminus fragments. (D) FLNA binding to Lrp6 is localized to a region of the C-terminus, as contained within Lrp6-CT1 (amino acids 1394-1499). The Lrp6 C-terminus (Lrp6-CT) was subdivided into three fragments (CT1, CT2 and CT3), each overlapping by ∼50 amino acids. The upper panel demonstrates that FLNA-C is pulled down by Lrp6-CT and Lrp6-CT1, and the lower panel shows the purified Lrp6 C-terminus fragments. Asterisks indicate bands of correct sizes for the fragments. (E) The Lrp6 binding site for FlnA was further refined to the Lrp6 C-terminus (amino acids 1394-1423). Regions of Lrp6 fragments are illustrated at the top. Western blot analysis shows that the strongest interaction with FlnA occurs with Lrp6-1394/1423, although weaker binding is also seen with Lrp6-1424/1451, suggesting that multiple site interactions exist for FlnA binding. Asterisks label correct sizes of undegraded fragments. (F) Immunocytochemistry shows overlapping Lrp6 and FlnA expression on the cell membrane and in cytoplasmic vesicles (arrows) of cultured neural progenitors. (G) Lrp6 also overlaps with Fmn2 on the cell membrane (arrow) and in perinuclear vesicles of cultured neural progenitors (arrowheads). (H) Lrp6 localization is dependent on FlnA. Loss of FLNA in M2 melanoma cells leads to diminished Lrp6 localization along the lamellapodia, as compared with A7 FLNA-repleted cells (arrowheads). Higher magnification images of the boxed regions are shown to the right. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue) in all images. Scale bars: 10 μm in F-H.

Consistent with a physical interaction between these two proteins, Lrp6 was highly expressed in brain, bone and spinal cord (Fig. S6D) and was localized to the ventricular zone and molecular layer in E13.5 cortex, in much the same manner as FlnA (Fig. S6E). Third, immunostaining of Lrp6 and FlnA on spreading neural progenitor cells showed that Lrp6 expression overlapped with that of FlnA at the cell membrane periphery and in vesicles (Fig. 5F). Fourth, Lrp6 also highly colocalized with Fmn2 on the cell membrane and in vesicles in the perinuclear region of cultured neural progenitors (Fig. 5G). Lastly, immunostaining of M2 (FLNA-depleted melanoma cell line) and A7 (FLNA-repleted cell line) cells showed that Lrp6 was highly localized in the lamellipodia of A7 cells, but not of M2 cells (Fig. 5G), suggesting that FlnA regulates Lrp6 stabilization on the membrane.

Collectively, these observations suggested that FlnA and Fmn2 might participate in the regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway through Dvl2 and Lrp6 at the peripheral cell membrane.

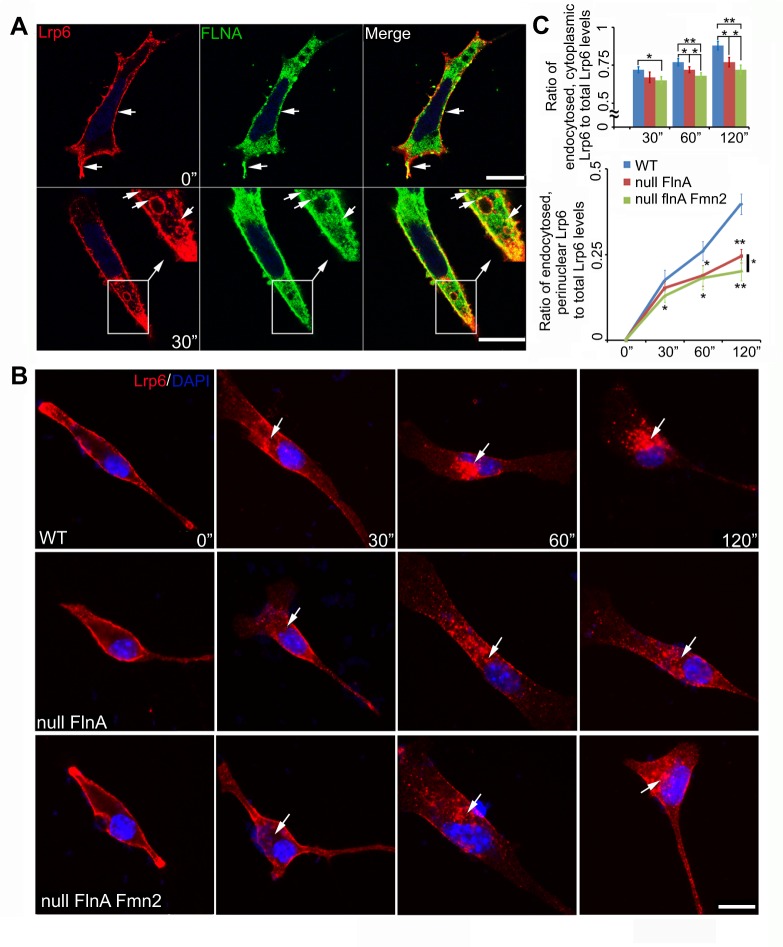

FlnA and Fmn2 mediate Lrp6 endocytosis at the membrane

As FlnA and Fmn2 were localized on membranes and cytoplasmic vesicles, and Fmn2 further colocalized with the lipid raft-associated protein caveolin and endocytosed with CTB (Fig. S1A, Fig. 2E,F), we investigated whether FlnA and Fmn2 regulate the endocytosis of Wnt-associated proteins such as Lrp6. We first labeled surface Lrp6 by incubating with anti-Lrp6 antibody and CTB in HEK 293 cells, and observed their endocytosis after 30 min. We found that Lrp6 and CTB were transported to similar perinuclear vesicular endosomes (Fig. S6F), suggesting that Lrp6, as a lipid protein, could share a similar endocytic mechanism with CTB. FlnA was also localized to endocytosed Lrp6 vesicles (Fig. 6A). Examination of CTB-dependent endocytosis over time in FLNA-depleted M2 and FLNA-repleted A7 cells showed that although CTB could be endocytosed normally into the cytosol, the rate of CTB transport to the perinuclear region was significantly impaired in FLNA-depleted M2 cells (Fig. S6G,H). Finally, we labeled Lrp6-expressing neural progenitor cells with anti-Lrp6 antibody and quantified the rate of Lrp6 endocytosis in WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null cells at various incubation times (Fig. 6B,C). The amount of Lrp6 endocytosed into the cytosol in Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors was significantly decreased at 60 and 120 min compared with WT and Flna null cells. The rate of Lrp6 endocytosis to the perinuclear region in Flna+Fmn2 null cells was also diminished compared with Flna null or WT cells. To demonstrate the specificity of this pathway, we also examined transferrin receptor-mediated endocytosis. Transferrin was endocytosed into cytosol within 5 min and to the perinuclear region (colocalization with the Golgi) after 20 min, but the rates of endocytosis in WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitor cells were not significantly different (Fig. S6I,J). Thus, loss of Flna and Fmn2 specifically impaired the rate of Lrp6 endocytosis to a greater degree than loss of FlnA alone, thereby potentially affecting Wnt signaling transduction from the membrane to the perinuclear region.

Fig. 6.

Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impairs the rate of Lrp6 endocytosis. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs show that FlnA (Fluorescein) and Lrp6 (Rhodamine) colocalize and undergo endocytosis into cytoplasmic vesicles. Neural progenitor cells transiently expressing Lrp6 were incubated with anti-Lrp6 antibody on ice for 40 min, then either fixed immediately (0 min) or incubated at 37°C for endocytosis (30-120 min). The top row shows that surface Lrp6 overlaps with FlnA on the cell membrane prior to endocytosis; the bottom row indicates that FlnA is localized with Lrp6-endocytosized vesicles (arrows) 30 min post-incubation. (B) Loss of both FlnA and Fmn2 impairs the rate of Lrp6 endocytosis, as compared with loss of FlnA alone. Fluorescent photomicrographs show representative Lrp6 endocytosis in WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors cultured in medium containing Lrp6 antibody and Wnt3a. Lrp6 endocytosis (arrows) was examined at various time points post-incubation at 37°C by staining for anti-Lrp6 with secondary antibody (Rhodamine). (C) Quantification of the rate of Lrp6 endocytosis into the cytosol and then to the perinuclear region. (Top) Lrp6 endocytosis in Flna+Fmn2 null cells is decreased by 9.7%, 11.3% and 17% at 30, 60 and 120 min, respectively, compared with that in WT cells. The rate of endocytosis was also significantly slower than that in Flna null cells, by 3.0%, 5.8% and 6.5% at these same time points. (Bottom) The rate of Lrp6 transport to the perinuclear region in Flna+Fmn2 null cells was decreased by 25%, 31% and 48% compared with that in WT cells, and by 14%, 3.2% and 17% compared with Flna null cells. Total or endocytosed Lrp6 levels were measured with ImageJ. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.d. Scale bars: 10 µm in A,B.

To further confirm FlnA effects on Lrp6 endocytosis we made two constructs, pCAG-Lrp6d1394/1424-GFP and pCAG-Lrp6d1394/1500-GFP (Fig. S7B), which lacked the FlnA binding site of Lrp6 as shown above (Fig. 5). We transfected either of these two constructs into neural progenitor cells, and followed their endocytosis at various times using anti-Lrp6 antibody surface labeling. WT-Lrp6-GFP was labeled and endocytosed normally, whereas both of the mutated Lrp6-GFP constructs showed negligible labeling and endocytosis from the cell surface in neural progenitors, even though their expression was normal in these cells (Fig. S7A-C). These results further implied that the FlnA-Lrp6 interaction is important for plasma membrane localization and Lrp6 endocytosis.

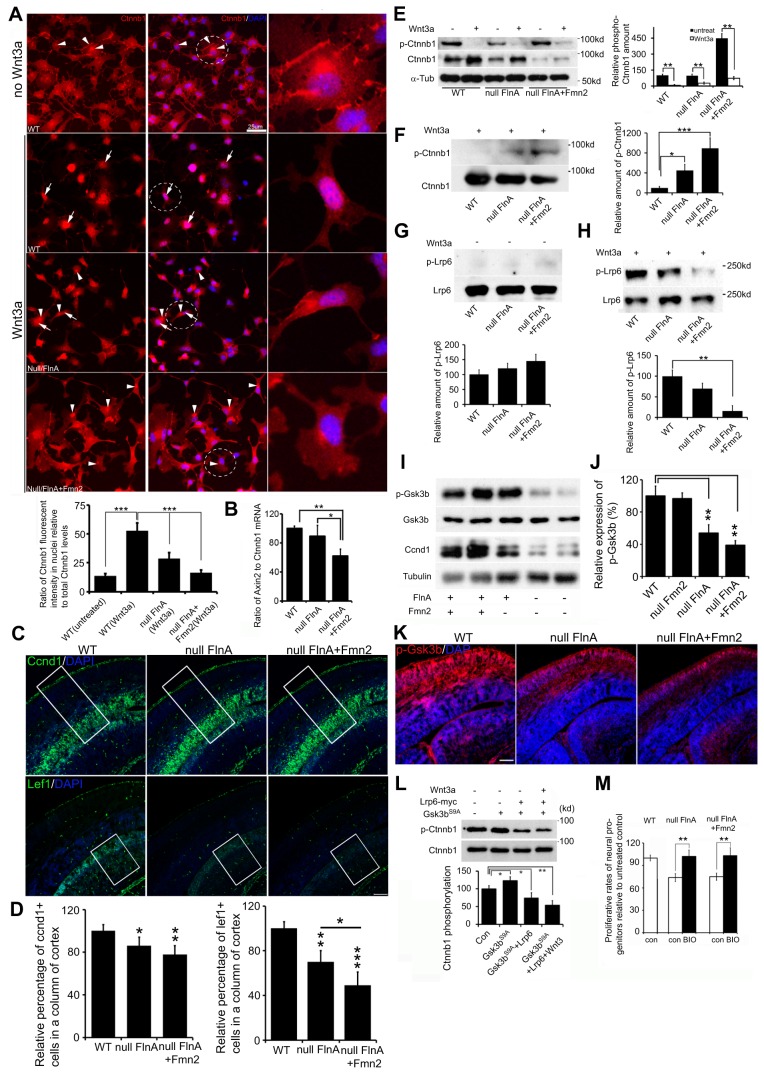

FlnA- and Fmn2-dependent neural proliferation defects are mediated through Wnt3a activation of Lrp6 phosphorylation and subsequent Gsk3β activation

Binding of a Wnt ligand to its transmembrane co-receptors inhibits phosphorylation and degradation of the transcriptional coactivator β-catenin, which then translocates to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression. The Wnt co-receptor Lrp6 is required for signal transduction and is sufficient to activate Wnt signaling when overexpressed. Lrp6 has been proposed to stabilize β-catenin by stimulating the degradation of axin, a scaffold protein required for β-catenin degradation. To explore the consequences of impaired Lrp6 receptor transport due to loss of FlnA and Fmn2, we first examined changes in β-catenin (Ctnnb1) localization in neural progenitor cells following Wnt3a stimulation. β-catenin is localized in the cytoplasm and along the cell membrane of untreated neural progenitor cells (including WT, Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null cells). Markedly less nuclear localization was observed in these untreated cells (Fig. 7A, top). As expected, Wnt3a treatment causes a significant increase in the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in WT cells (Fig. 7A, second row). By contrast, significantly reduced levels of β-catenin are seen in the nuclei of Flna null neural progenitor cells following Wnt3a treatment (Fig. 7A, third row), suggesting that loss of FlnA impairs Lrp6-dependent activation of the Wnt signaling cascade. This reduction is even more apparent in the Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors (Fig. 7A, bottom), consistent with the impairment of Lrp6 receptor transport due to impaired stability at the membrane.

Fig. 7.

Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impairs Wnt downstream signaling transduction. (A) Loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impairs Wnt3a-stimulated nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Neural progenitor cells were treated with Wnt3a for 3-6 h, and then stained with anti-β-catenin and counterstained with DAPI. β-catenin was localized in the cytosol and at the cytoplasmic membrane in untreated neural progenitor cells (only WT cell staining is shown). Nuclear accumulation of β-catenin was increased in WT cells but not in Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null cells after Wnt3a treatment. Statistical analysis (from three repeat assays) showed that the fluorescence intensity of β-catenin in nuclei of Flna+Fmn2 null cells was significantly lower than in WT and Flna null cells. n>12 samples were used for each time point. (B) Digital PCR shows that the Axin2 transcript, a Wnt downstream target, is significantly decreased in Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors compared with Flna null and WT cells, indicating diminished Wnt signaling activity in Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors. (C) Fluorescent photomicrographs showing that the number of Ccnd1+ cells and Lef1+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null E15.5 cortex is reduced compared with littermate WT and Flna null cortices. (D) Statistical analyses show that the number of Ccnd1+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null cortex is reduced by about 6% and 20% and the number of Lef1+ cells is reduced by 20% and 50%, as compared with Flna null and WT cortices, respectively. (E) Wnt3a stimulation promotes β-catenin expression in WT and Flna null neural progenitor cells and inhibits β-catenin phosphorylation in these cells. Statistical analyses (right) show that relative amounts of phospho-β-catenin are significantly decreased after Wnt3a stimulation. (F) Western blot demonstrates a decrease in phospho-β-catenin in WT control neural cells following Wnt3a stimulation. The decrease in β-catenin phosphorylation is impaired in Flna null cells and more so in Flna+Fmn2 null cells. Results are quantified (right) from n>3 independent assays. (G) Western blot demonstrates no significant difference in phospho-Lrp6 following loss of FlnA or of FlnA and Fmn2 compared with WT in the absence of Wnt3a stimulation. Results are quantified (beneath) from n>3 independent assays. (H) Western blot shows impaired Lrp6 phosphorylation after Wnt3a stimulation in the Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural cells. Results are quantified (beneath) from n>3 independent assays. (I) Western blot shows that Gsk3β phosphorylation (Ser9) levels in Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null brains are decreased. The expression of Ccnd1 is also diminished in the brain lysates. (J) Statistical analyses show that the levels of phospho-Gsk3β in Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null brains are significantly decreased. (K) Fluorescent photomicrographs of E15.5 brains following immunostaining show progressively reduced phospho-Gsk3β (pSer9) levels (Rhodamine) in Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null cortices. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI. (L) Lrp6 overexpression inhibits Gsk3βS9A phosphorylation of β-catenin. Gsk3βS9A is a constitutively active, non-phosphorylated Gsk3β with serine to alanine substitution. Statistical analysis (n>3) shows that Lrp6 expression significantly decreases Gsk3βS9A phosphorylation of β-catenin, and Wnt3a (200 ng/ml) stimulation further increases the inhibitory effect of Lrp6 on β-catenin phosphorylation. (M) Treatment with the Gsk3β inhibitor BIO rescues the proliferation of Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitor cells. Proliferative rates for Flna null or Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors are reduced by ∼25% compared with WT control. BIO treatment leads to recovery in the proliferative rates of both Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitor cells, to a level comparable to that seen in untreated WT cells. Neural progenitor cells were cultured in NPC medium with or without 1 μM BIO for 48 h, and total cell numbers were determined by cell counting. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.d. Scale bars: 10 μm in A; 100 μm in C,K.

To examine how impaired Lrp6-dependent transport might affect different components of Wnt signaling transduction, we first evaluated axin levels by digital PCR, as a measure of β-catenin activation. We observed the most dramatic decline in Axin2 mRNA levels in Flna+Fmn2 null progenitors, as compared with Flna null and WT neural progenitors (Fig. 7B). Axin protein expression in E15.5 Flna+Fmn2 null brain was similarly decreased when assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. S7D,E). Second, we examined the expression of other downstream target genes, such as Ccnd1 and Lef1. The number of Ccnd1+ cells in both E13.5 and E15.5 Flna+Fmn2 null brains was significantly decreased (Fig. 7C,D, Fig. S7D,E), consistent with diminished Wnt3a-stimulated nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in Flna+Fmn2 null cells. The decrease in Ccnd1+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null brain was greatest along the cortical hem (Fig. S7D, arrow), where Wnt expression is concentrated. Ccnd1 was similarly reduced in Flna+Fmn2 null brain lysate (Fig. 7I). Similar to Ccnd1, the number of Lef1+ cells in Flna+Fmn2 null brains was severely compromised (Fig. 7C,D, Fig. S7D,E). Third, Wnt3a stimulation caused a significant increase in total β-catenin but a decrease in phospho-β-catenin levels in WT neural progenitor cells (Fig. 7E), demonstrating Wnt signaling transduction effects on β-catenin phosphorylation and stabilization in neural cells. Loss of FlnA or of FlnA and Fmn2 led to increased β-catenin phosphorylation after Wnt3a stimulation, suggesting a disruption in Lrp6-mediated signaling (Fig. 7F). Finally, Lrp6 phosphorylation is impaired in Flna null and Flna+Fmn2 null neural cells after Wnt3a application (Fig. 7G,H), and could be responsible for the phenotypic changes seen upon disruption of these actin-associated trafficking proteins.

Previous work has shown that Lrp6 phosphorylation inhibits β-catenin phosphorylation via Gsk3β (Niehrs and Shen, 2010; Piao et al., 2008). Gsk3β phosphorylates β-catenin and promotes its degradation in the downstream Wnt signaling cascade, thereby limiting β-catenin nuclear translocalization and transcriptional activation. Thus, activation or inhibition of Gsk3β is crucial to the Wnt signaling cascade. We examined Gsk3β activity in developing brains by western blot and immunostaining, and discerned a significant difference in phospho-Gsk3β (pSer9) levels between WT and Flna+Fmn2 null tissues (Fig. 7I-K), suggesting that FlnA and Fmn2 effected Wnt downstream signaling.

To address the extent to which Lrp6 is responsible for the defects in the Flna and Fmn2 mutant mice, we examined whether altering downstream Gsk3β activity could rescue the changes in β-catenin phosphorylation and nuclear localization, and the proliferation defects seen with loss of this trafficking pathway. First, Lrp6 alone or after Wnt3a stimulation inhibited Gsk3β phosphorylation of β-catenin (Fig. 7L, Fig. S8A), consistent with the observed increase in phospho-β-catenin with loss of FlnA or of FlnA and Fmn2 (due to impaired Lrp6 activation). Second, β-catenin immunocytochemistry performed on cultured neural progenitors showed strong β-catenin nuclear accumulation in most WT neural progenitor cells but diminished accumulation in Flna null or Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors following a 2 h treatment with the Gsk3β inhibitor LiCl (Fig. S8B,C). Conversely, the number of cells showing nuclear accumulation of β-catenin after co-expressing Lrp6 with the constitutively active, unphosphorylated Gsk3β S9A was significantly increased compared with those expressing Gsk3βS9A alone (Fig. S8D,E). These observations suggested that loss of FlnA and Fmn2 impaired Wnt3a-Lrp6 signaling, which inhibits Gsk3β-dependent phosphorylation on β-catenin.

Lastly, we tested whether activating Wnt downstream signals could rescue neural progenitor proliferation. We initially observed that Lrp6 did not directly regulate Gsk3β activity through the Gsk3β phosphorylation domains (Fig. S8F). This provided a means to circumvent and/or overcome Wnt3a-Lrp6 effects on Gsk3β activity in the Wnt signaling cascade. We next confirmed that the Gsk3β inhibitor BIO led to a decrease in active phosphorylation (pY216) of Gsk3β and an increase in inhibitory phosphorylation at Ser9 (Fig. S8G,H). BIO treatment of Flna null or Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors led to rescue of the proliferation defect to the same levels seen in WT cells (Fig. 7M), implying that inhibition of Gsk3β activity is a key factor for FlnA- and Fmn2-dependent cell proliferation.

In total, our findings indicate that FlnA and Fmn2 together have a regulatory function in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by mediating Lrp6 endocytosis, Gsk3β inactivation, and subsequent nuclear transport of β-catenin, presumably targeting gene expression and neural proliferation.

DISCUSSION

Actin cytoskeletal regulation in development has often been linked to the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway and PCP (Amin and Vincan, 2012). The PCP pathway is activated via binding of Wnt to Fz and its co-receptors (Nrh1, Ryk, Ptk7 or Ror2). The receptor then recruits Dishevelled (Dvl), which forms a complex with Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis (Daam) in Drosophila. Daam, a Formin homology associated protein, then activates the small G-protein Rho through a guanine exchange factor. Rho activates Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), which is one of the major regulators of the cytoskeleton. Dvl also mediates profilin binding to actin, which can result in restructuring of the cytoskeleton. Changes in the actin cytoskeleton direct PCP to maintain the neuroepithelium. Our current studies now provide a parallel mechanism for actin cytoskeletal regulation through the canonical Wnt pathway. Binding of Wnt to Fz and its co-receptor (Lrp5/6) also recruits Dvl2. Much in the same manner as the actin-binding profilin, the actin-binding FlnA interacts with Dvl2, as well as the Formin homology protein Fmn2. However, rather than effecting cell polarity through modification of cytoskeletal structure, the actin-nucleating Fmn2 and FlnA actually mediate endocytosis of the Lrp6 co-receptor and thereby regulate Gsk3β- and β-catenin-dependent signaling that directs neural proliferation. Collectively, these actin-dependent processes oversee neural progenitor proliferation and maintenance of the polarized neuroepithelium in a highly coordinated fashion.

Several studies implicate actin-dependent endocytosis and vesicle trafficking in the regulation of progenitor proliferation through a Wnt-dependent pathway. Our recent work has shown that FlnA directly interacts with Big2 (brefeldin A inhibited guanine exchange factor 2; also known as Arfgef2). Big2 regulates GDP to GTP conversion of the ADP-ribosylation factors (Arfs) that are required for vesicle coat formation during endocytosis (Zhang et al., 2013, 2012). Loss of BIG2 function in humans leads to microcephaly, consistent with a neural proliferative defect (Sheen et al., 2004). FlnA also binds the integral membrane protein caveolin, which is involved in receptor-independent endocytosis (Stahlhut and van Deurs, 2000; Sverdlov et al., 2009). Caveolin is necessary for Wnt3a-dependent internalization of Lrp6 (Yamamoto et al., 2006). Wnt signaling also triggers sequestration of Gsk3β from the cytosol into multivesicular bodies (late endosomes), thereby inhibiting Gsk3β-dependent protease degradation (Taelman et al., 2010). Sequestration of Gsk3β extends the half-life of many proteins, including β-catenin. Lrp5/6 and β-catenin have been implicated in G1-to-S and G2-to-M phase progression in the regulation of neural progenitor proliferation. This same pattern of cell cycle regulation has been shown with loss of FlnA function (Lian et al., 2012). Overall, these studies begin to delineate a specific pathway involving actin-dependent vesicle trafficking in regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway.

A defect in actin-dependent endocytosis might lead to more extensive problems with vesicle trafficking. Our current studies show that while FlnA stabilizes both Fmn2 and Lrp6 localization at the cell membrane prior to endocytosis, both FlnA and Fmn2 also direct the rate at which Lrp6 is endocytosed and ultimately transported to the perinuclear region. These observations are consistent with a general role for Formins as Rho GTPase effector proteins, whereby activated Rho GTPases lead to loss of Formin autoinhibition. Release of inhibition allows for the activation of Formin domains that mediate interaction with other proteins (FH1 to FH3). The proline-rich FH1 domain is responsible for polymerization of actin in a single direction, thereby establishing polarity and the directionality of trafficked vesicles. Similar to Daam1, Fmn2 has a Rho GTPase-binding domain and a proline-rich actin-nucleating domain. Fmn2 has also recently been implicated in long-range actin-dependent vesicle transport (Schuh, 2011). Changes in trafficking, however, might not only affect the internalization and transport of proteins to various cytoplasmic compartments but also the rate of degradation of particular proteins. The Fmn2 proline-rich FH1 domain not only binds profilin, but may also mediate interactions with WW domain proteins. WW domains are found in E3 ubiquitin protein ligases, which direct trafficking and lysosomal/proteasomal degradation. A potential role for Fmn2 in the ubiquitylation/lysosomal degradation pathway, in the context of Wnt signaling, requires further exploration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The Flna null mouse strain was obtained from Comparative and Developmental Genetics Department, MRC Human Genetics Unit, Edinburgh, UK. Fmn2 knockout and Fmn2-GFP transgenic mice were provided by Dr Philip Leder (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA). Mouse studies were performed with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Harvard Medical School and of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Details of genotyping are provided in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Routine histology, in situ hybridization and immunostaining

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red staining and immunostainings, as well as in situ hybridization, were performed as reported previously (Ferland et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2007) (Lian et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2006). Images were obtained with an Axioskop or LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Zeiss). For further details, including antibodies and titers, see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Yeast two-hybrid screen

The C-terminal fragment of human FLNA (amino acids 2167-2648) served as the bait with insertion into the pNLex vector, as previously described (Sheen et al., 2002). The potential prey genes from an E12 mouse brain mRNA library were screened with the Matchmaker yeast two-hybrid system (Clontech, K1615-1). Further details are provided in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Cell culture and transfections

Neural progenitor cells, primary MEFs, M2/A7, Neuro-2 and HEK 293 cells were cultured as described previously (Lian et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2011; Sheen et al., 2006). The Fmn2-GFP or Lrp6-GFP constructs were transiently transfected into the cells for 5-8 h. For co-immunoprecipitation, cells were transfected with myc-FLNA/B and Fmn2-GFP, Fmn2-GFP only, or Flag-Dvl2 and myc-FLNA constructs for 24 h, and then lysed for assays. Lrp6-myc construct was transfected into cells overnight for the endocytosis assay. For details of construct design, co-immunoprecipitation (including antibodies), and further information on cell culture and transfection see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Functional assays

The membrane flotation assay to assess Fmn2 association with membranes and radioimmunoprecipitation to assess Fmn2 myristoylation were performed on transfected HEK 293 cell lysates as described in the supplementary Materials and Methods. CTB and Lrp6 endocytosis and β-catenin nuclear accumulation studies were performed as described in the supplementary Materials and Methods. For the Gsk3β rescue assay, neural progenitors were treated with BIO as detailed in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Digital PCR

cDNA prepared from total RNA of WT, Flna null or Flna+Fmn2 null neural progenitors was assessed by digital PCR using Axin2 and Ctnnb1 TaqMan probes and quantified as described in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Western blot

Western blot was performed on protein extracts of E13.5 or E15.5 mouse tissues or of cultured cells using the antibodies and dilations listed in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical analyses

Serial tissue sections, cell numbers and western blots were counted and/or quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Data are represented as the mean (n≥3) ±s.d. t-value (two-tailed test) was calculated using the following formula:

|

(1) |

P-value was calculated using the online resource www.socscistatistics.com. Significance was determined as P<0.05.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fumihiko Nakamura for the gift of anti-FLNA antibodies (1-7 and 4-4), and M2 and A7 cells.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

J.L. contributed skeletal preparation; A.C. contributed to the axin/catenin assay; M.De. contributed to the Fmn2 myristoylation studies; M.Do. contributed to the axin2 mRNA quantification assay and analysis; T.W. contributed to data analysis; G.L. contributed to experiments and design, data analysis and manuscript preparation; and V.S. contributed experimental design, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [1R01NS092062-01 to V.S.]; and in part by the Empire State Stem Cell Fund through the New York State Department of Health [contract #C024324 to V.S.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.139295.supplemental

References

- Amin N. and Vincan E. (2012). The Wnt signaling pathways and cell adhesion. Front. Biosci. 17, 784-804. 10.2741/3957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan S., Schultz J. and Grosshans J. (2014). Formin’ cellular structures: physiological roles of Diaphanous (Dia) in actin dynamics. Commun. Integr. Biol. 6, e27634 10.4161/cib.27634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna B., Jenny A., Lee D., Mlodzik M. and Schier A. F. (2006). Planar cell polarity signalling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation. Nature 439, 220-224. 10.1038/nature04375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettenhofer M., Zhou F. and Leder P. (2008). Formin 1-isoform IV deficient cells exhibit defects in cell spreading and focal adhesion formation. PLoS ONE 3, e2497 10.1371/journal.pone.0002497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanto M., Weber U., Strutt D. I. and Mlodzik M. (2000). Nuclear signaling by Rac and Rho GTPases is required in the establishment of epithelial planar polarity in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 10, 979-988. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00645-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland R. J., Batiz L. F., Neal J., Lian G., Bundock E., Lu J., Hsiao Y.-C., Diamond R., Mei D., Banham A. H. et al. (2009). Disruption of neural progenitors along the ventricular and subventricular zones in periventricular heterotopia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 497-516. 10.1093/hmg/ddn377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlin J. B., Yamin R., Egan S., Stewart M., Stossel T. P., Kwiatkowski D. J. and Hartwig J. H. (1990). Human endothelial actin-binding protein (ABP-280, nonmuscle filamin): a molecular leaf spring. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1089-1105. 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju R., Cirone P., Lin S., Griesbach H., Slusarski D. C. and Crews C. M. (2010). Activation of the planar cell polarity formin DAAM1 leads to inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6906-6911. 10.1073/pnas.1001075107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. E., Huang H., Zhao M., Zhang X., Zhang A., Semonov M. V., MacDonald B. T., Garcia Abreu J., Peng L. and He X. (2013). Wnt stabilization of beta-catenin reveals principles for morphogen receptor-scaffold assemblies. Science 340, 867-870. 10.1126/science.1232389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian G., Lu J., Hu J., Zhang J., Cross S. H., Ferland R. J. and Sheen V. L. (2012). Filamin a regulates neural progenitor proliferation and cortical size through Wee1-dependent Cdk1 phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 32, 7672-7684. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0894-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Tiao G., Folkerth R., Hecht J., Walsh C. and Sheen V. (2006). Overlapping expression of ARFGEF2 and Filamin A in the neuroependymal lining of the lateral ventricles: insights into the cause of periventricular heterotopia. J. Comp. Neurol. 494, 476-484. 10.1002/cne.20806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Lian G., Lenkinski R., De Grand A., Vaid R. R., Bryce T., Stasenko M., Boskey A., Walsh C. and Sheen V. (2007). Filamin B mutations cause chondrocyte defects in skeletal development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 1661-1675. 10.1093/hmg/ddm114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Delli-Bovi L. C., Hecht J., Folkerth R. and Sheen V. L. (2011). Generation of neural stem cells from discarded human fetal cortical tissue. J. Vis. Exp. 2681 10.3791/2681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Niehrs C. and Shen J. (2010). Regulation of Lrp6 phosphorylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2551-2562. 10.1007/s00018-010-0329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao S., Lee S.-H., Kim H., Yum S., Stamos J. L., Xu Y., Lee S.-J., Lee J., Oh S., Han J.-K. et al. (2008). Direct inhibition of GSK3beta by the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of LRP6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS ONE 3, e4046 10.1371/journal.pone.0004046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson K. I., Brennan J., Monkley S., Avery B. J. and Skarnes W. C. (2000). An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature 407, 535-538. 10.1038/35035124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A., Khadka D. K., Liu W., Bharti R., Runnels L. W., Dawid I. B. and Habas R. (2006). Profilin is an effector for Daam1 in non-canonical Wnt signaling and is required for vertebrate gastrulation. Development 133, 4219-4231. 10.1242/dev.02590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh M. (2011). An actin-dependent mechanism for long-range vesicle transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1431-1436. 10.1038/ncb2353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen V. L., Feng Y., Graham D., Takafuta T., Shapiro S. S. and Walsh C. A. (2002). Filamin A and Filamin B are co-expressed within neurons during periods of neuronal migration and can physically interact. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2845-2854. 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen V. L., Ganesh V. S., Topcu M., Sebire G., Bodell A., Hill R. S., Grant P. E., Shugart Y. Y., Imitola J., Khoury S. J. et al. (2004). Mutations in ARFGEF2 implicate vesicle trafficking in neural progenitor proliferation and migration in the human cerebral cortex. Nat. Genet. 36, 69-76. 10.1038/ng1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen V. L., Ferland R. J., Harney M., Hill R. S., Neal J., Banham A. H., Brown P., Chenn A., Corbo J., Hecht J. et al. (2006). Impaired proliferation and migration in human Miller-Dieker neural precursors. Ann. Neurol. 60, 137-144. 10.1002/ana.20843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoglund P. and Keller R. (2010). Integration of planar cell polarity and ECM signaling in elongation of the vertebrate body plan. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 589-596. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlhut M. and van Deurs B. (2000). Identification of filamin as a novel ligand for caveolin-1: evidence for the organization of caveolin-1-associated membrane domains by the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 325-337. 10.1091/mbc.11.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sverdlov M., Shinin V., Place A. T., Castellon M. and Minshall R. D. (2009). Filamin A regulates caveolae internalization and trafficking in endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4531-4540. 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-0997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taelman V. F., Dobrowolski R., Plouhinec J.-L., Fuentealba L. C., Vorwald P. P., Gumper I., Sabatini D. D. and De Robertis E. M. (2010). Wnt signaling requires sequestration of glycogen synthase kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell 143, 1136-1148. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Komekado H. and Kikuchi A. (2006). Caveolin is necessary for Wnt-3a-dependent internalization of LRP6 and accumulation of beta-catenin. Dev. Cell 11, 213-223. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Neal J., Lian G., Shi B., Ferland R. J. and Sheen V. (2012). Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine exchange factor 2 regulates filamin A phosphorylation and neuronal migration. J. Neurosci. 32, 12619-12629. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1063-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Neal J., Lian G., Hu J., Lu J. and Sheen V. (2013). Filamin A regulates neuronal migration through Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine exchange factor 2-dependent Arf1 activation. J. Neurosci. 33, 15735-15746. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]